Cardiac Evaluation before and after Oral Propranolol Treatment for Infantile Hemangiomas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Treatment Protocol

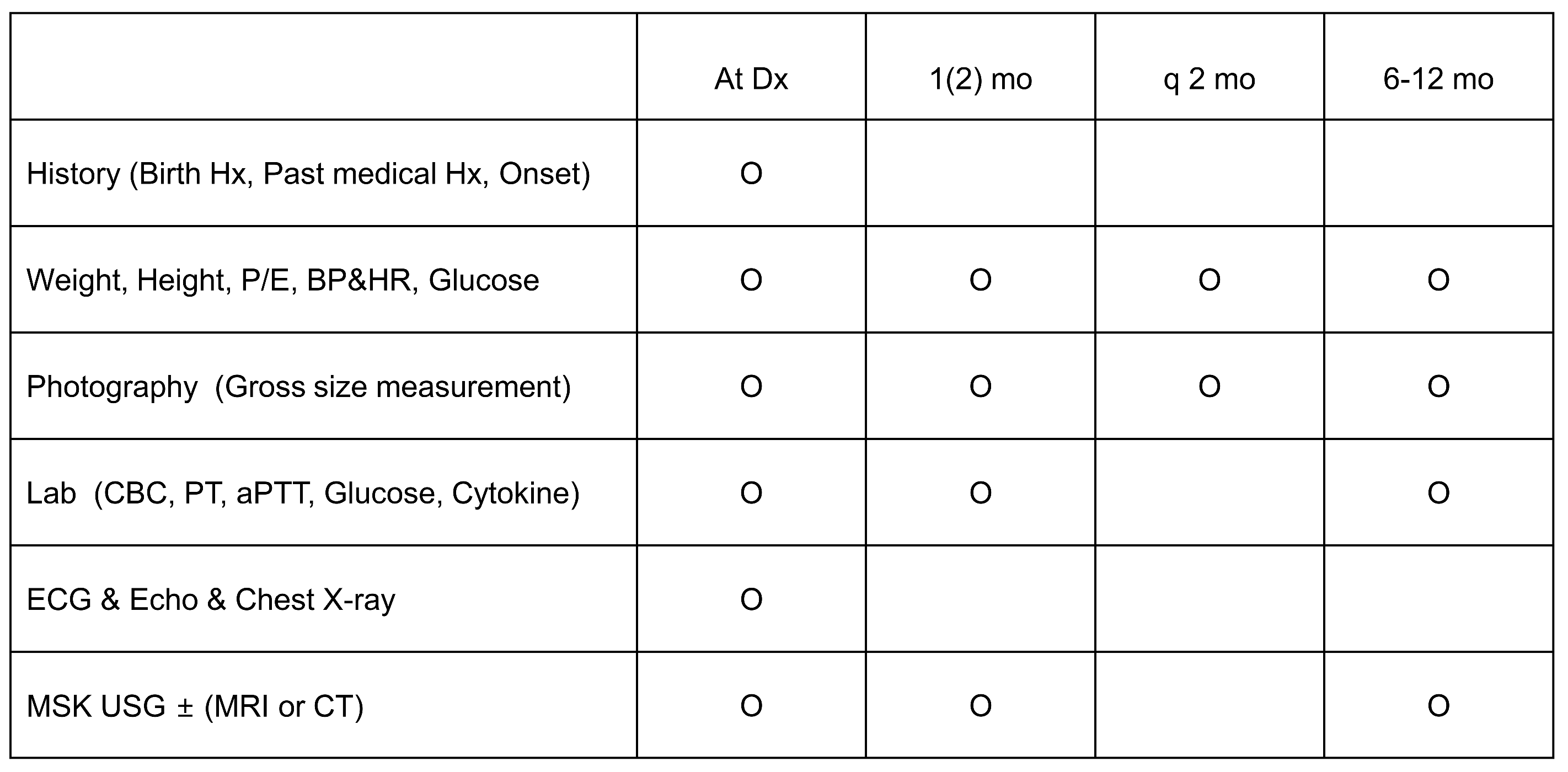

2.3. Efficacy and Safety Assessments (Figure 1)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Echocardiography to Evaluate CHD

3.3. Echocardiography to Assess Cardiac Function

3.4. ECG and Holter Monitoring to Assess Arrhythmia(s)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, M. Vascular anomaly: An updated review. Clin. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 26, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.L. Update on infantile hemangioma. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 64, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, Z.R.; Frieden, I.J.; Garzon, M.C.; Mully, T.W.; Drolet, B.A. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis: An evidence-based review of case reports in the literature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Teng, P.; Xu, H.; Ma, L.; Ni, Y. Cardiac hemangioma: A comprehensive analysis of 200 cases. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 99, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krowchuk, D.P.; Frieden, I.J.; Mancini, A.J.; Darrow, D.H.; Blei, F.; Greene, A.K.; Annam, A.; Baker, C.N.; Frommelt, P.C.; Hodak, A.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeger, P.H.; Harper, J.I.; Baselga, E.; Bonnet, D.; Boon, L.M.; Atti, M.C.D.; El Hachem, M.; Oranje, A.P.; Rubin, A.T.; Weibel, L.; et al. Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: Recommendations of a European expert group. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithson, S.L.; Rademaker, M.; Adams, S.; Bade, S.; Bekhor, P.; Davidson, S.; Dore, A.; Drummond, C.; Fischer, G.; Gin, A.; et al. Consensus statement for the treatment of infantile haemangiomas with propranolol. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2017, 58, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, H.; Akita, S.; Fujino, A.; Jinnin, M.; Ozaki, M.; Osuga, K.; Nakaoka, H.; Morii, E.; Kuramochi, A.; Aoki, Y.; et al. Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Anomalies 2017. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, e138–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léauté-Labrèze, C.; Dumas de la Roque, E.; Hubiche, T.; Boralevi, F.; Thambo, J.B.; Taïeb, A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2649–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaute-Labreze, C.; Boccara, O.; Degrugillier-Chopinet, C.; Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Prey, S.; Lebbe, G.; Gautier, S.; Ortis, V.; Lafon, M.; Montagne, A.; et al. Safety of oral propranolol for the treatment of infantile hemangioma: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frongia, G.; Byeon, J.O.; Arnold, R.; Mehrabi, A.; Günther, P. Cardiac diagnostics before oral propranolol therapy in infantile hemangioma: Retrospective evaluation of 234 infants. World J. Pediatr. 2018, 14, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdoğan, İ.; Sarıalioğlu, F. Cardiac evaluation in children with hemangiomas. Turk Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2016, 44, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.L.; Mahendran, G.; Lawley, L.P. Is prolonged monitoring necessary? An updated approach to infantile hemangioma treatment with oral propranolol. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2021, 38, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F.; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, L.; Koch, H.; Bein, G.; Brockmeier, K. Left ventricular diastolic function in infants, children, and adolescents. Reference values and analysis of morphologic and physiologic determinants of echocardiographic Doppler flow signals during growth and maturation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 32, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallaire, F.; Slorach, C.; Hui, W.; Sarkola, T.; Friedberg, M.K.; Bradley, T.J.; Jaeggi, E.; Dragulescu, A.; Har, R.L.; Cherney, D.Z.; et al. Reference Values for Pulse Wave Doppler and Tissue Doppler Imaging in Pediatric Echocardiography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, e002167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Min, D.H.; Jung, H.L.; Shim, J.W.; Kim, D.S.; Shim, J.Y.; Park, M.S.; Park, H.J.; Lee, S.Y. Propranolol as a first-line treatment for pediatric hemangioma: Outcome of a single institution over one year. Clin. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 23, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Mostyn, R.H.; Oram, S. Modification by propranolol of cardiovascular effects of induced hypoglycaemia. Lancet 1975, 1, 1213–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, J.J.; Khan, Z.A. Mechanisms of propranolol action in infantile hemangioma. Dermatoendocrinology 2015, 6, e979699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosoni, A.; Cutrone, M.; Dalle Carbonare, M.; Pettenazzo, A.; Perilongo, G.; Sartori, S. Cardiac arrest in a toddler treated with propranolol for infantile Hemangioma: A case report. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosbe, K.W.; Suh, K.Y.; Meyer, A.K.; Maguiness, S.M.; Frieden, I.J. Propranolol in the management of airway infantile hemangiomas. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 136, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.D.; Merrill, T.; Gardner, J.R.; Collins, R.T.; Sanchez, J.; Johnson, A.B.; Eble, B.K.; Hartzell, L.D.; Kincannon, J.M.; Richter, G.T. Clinical Significance of Screening Electrocardiograms for the Administration of Propranolol for Problematic Infantile Hemangiomas. Int. J. Pediatr. 2021, 2021, 6657796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, M.F.; Breugem, C.C.; Vlasveld, F.A.; de Graaf, M.; Slieker, M.G.; Pasmans, S.G.; Breur, J.M. Is cardiovascular evaluation necessary prior to and during beta-blocker therapy for infantile hemangiomas?: A cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.D.; Leeder, J.S.; Sterner, S. Glucagon therapy for beta-blocker overdose. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1984, 18, 394–398. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, F.; McElhinney, D.B.; Guarini, A.; Presti, S. Cardiac screening in infants with infantile hemangiomas before propranolol treatment. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawley, L.P.; Siegfried, E.; Todd, J.L. Propranolol treatment for hemangioma of infancy: Risks and recommendations. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2009, 26, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.I.; Kaplan, S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyme, J.L.; Thampan, A.; Han, E.J.; Nyirenda, T.L.; Kotb, M.E.; Shin, H.T. Propranolol for infantile haemangiomas: Initiating treatment on an outpatient basis. Cardiol. Young 2012, 22, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSwiney, E.; Murray, D.; Murphy, M. Propranolol therapy for cutaneous infantile haemangiomas initiated safely as a day-case procedure. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2014, 173, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solman, L.; Murabit, A.; Gnarra, M.; Harper, J.I.; Syed, S.B.; Glover, M. Propranolol for infantile haemangiomas: Single centre experience of 250 cases and proposed therapeutic protocol. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.J.; Penington, A.J.; Bekhor, P.S.; Crock, C.M. Use of propranolol for treatment of infantile haemangiomas in an outpatient setting. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 48, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Male/Female (n) | 21:43 |

| Median gestational age (weeks) b | 38.6 (32–41) |

| Preterm (n) (<37 w) | 12 |

| Birth weight (gram) a | 3085.4 ± 567.1 (1220–4380) |

| Low birth weight (n) (below 2500 g) | 10 |

| Hemangioma character | |

| Location (single/mutiple) (n) | 49:15 |

| Type (superficial/mixed/deep-seated) (n) | 38:11:17 |

| Hemangioma number (n) | 1.7 ± 1.0 (1–7) |

| Hemangioma size | |

| Longitudinal diameter (cm) a | |

| Initial | 2.8 ± 2.1 (0.3–12.0) |

| After 1 month | 2.1 ± 2.0 (0.0–11.0) |

| After 1 year | 2.0 ± 2.0 (0.0–7.6) |

| Average percentage of size decrease (%) | |

| After 1 month | 8.0 ± 114.2 |

| After 1 year | 71.8 ± 45.7 |

| Treatment | |

| Median age of diagnosis (weeks) b | 2.0 (0.10–34.3) |

| Median age at initial treatment (weeks) b | 13.6 (2.4–87.9) |

| Median duration of treatment (months) b | 8 (6–13) |

| Median weight at initial treatment (kg) | 7.0 ± 1.8 (3.2–11.6) |

| Cause of treatment (n) | |

| Risk of functional impairment | 10 |

| Local complication (ulceration, bleeding) | 3 |

| Risk of aesthetic impairment | 51 |

| Side effect patient (n) | 11 |

| Side effect character (n) | |

| Hypotension | 0 |

| Bradycardia | 1 |

| Hypoglycemia | 2 |

| Insomnia | 4 |

| Elevated liver enzyme | 3 |

| Echocardiography | Pre | Post | Coefficient (95% Confidence Interval) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional study | ||||

| Functional study | ||||

| LV function | ||||

| 2D EF (%) | 67.76 ± 4.03 | 69.11 ± 5.17 | −1.342 (−3.23 to 0.54) | 0.158 |

| 2D FS (%) | 35.76 ± 3.21 | 37.37 ± 4.03 | −1.61 (−3.11 to −0.11) | 0.036 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 46.21 ± 8.54 | 46.19 ± 9.25 | 0.022 (−3.13 to 3.17) | 0.989 |

| IVS thickness (mm) | 4.18 ± 0.75 | 4.14 ± 0.74 | 0.048 (−0.27 to 0.37) | 0.765 |

| LVPW thickness (mm) | 3.79 ± 0.5 | 3.81 ± 0.71 | −0.022 (−0.26 to 0.22) | 0.853 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 23.96 ± 4.01 | 28.23 ± 3.7 | −4.266 (−5.13 to −3.4) | <0.001 |

| LVESD (mm) | 15.31 ± 2.46 | 17.67 ± 2.91 | −2.363 (−3.07 to −1.65) | <0.001 |

| E/A ratio | 4.18 ± 0.75 | 4.14 ± 0.74 | −0.209 (−0.33 to −0.09) | 0.002 |

| E/e′ | 3.79 ± 0.5 | 3.81 ± 0.71 | 1.167 (0.37 to 1.97) | 0.005 |

| MAPSE (mm) | 23.96 ± 4.01 | 28.23 ± 3.7 | −0.059 (−0.73 to 0.61) | 0.859 |

| GLS | 15.31 ± 2.46 | 17.67 ± 2.91 | 1.162 (0.05 to 2.27) | 0.040 |

| 3D EF (%) | 64.07 ± 4.69 | 62.68 ± 4.05 | −1.393 (−3.421 to 0.635) | 0.170 |

| RV function | ||||

| TV e′ (m/s) | 9.92 ± 2.87 | 9.98 ± 2 | −0.003 (-0.02 to 0.01) | 0.662 |

| TV a′ (m/s) | −19.19 ± 2.2 | −20.35 ± 2.38 | 0.017 (0.001 to 0.03) | 0.035 |

| TV s′ (m/s) | 10.56 ± 2.3 | 9.39 ± 1.2 | −0.012 (−0.02 to −0.005) | 0.002 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 14.08 ± 2.41 | 15.36 ± 2.31 | 1.283 (0.407–2.159) | 0.006 |

| Morphologic study—congenital heart disease (n) | ||||

| Atrial septal defect | 6 | 2 | ||

| Persistent foramen ovale | 16 | 2 | ||

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 3 | 0 |

| Pre | Post | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | 120.15 ± 23.73 | 111.56 ± 22.47 | 8.58 (−0.55 to 17.73) | 0.065 |

| PR interval | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.004) | 0.263 |

| QRS duration | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.001) | 0.018 |

| QTc | 427.44 ± 20.31 | 425.74 ± 17.75 | 1.70 (−6.93 to 10.34) | 0.690 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwak, J.H.; Yang, A.; Jung, H.L.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.S.; Shim, J.Y.; Shim, J.W. Cardiac Evaluation before and after Oral Propranolol Treatment for Infantile Hemangiomas. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113332

Kwak JH, Yang A, Jung HL, Kim HJ, Kim DS, Shim JY, Shim JW. Cardiac Evaluation before and after Oral Propranolol Treatment for Infantile Hemangiomas. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(11):3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113332

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwak, Ji Hee, Aram Yang, Hye Lim Jung, Hyun Ju Kim, Deok Soo Kim, Jung Yeon Shim, and Jae Won Shim. 2024. "Cardiac Evaluation before and after Oral Propranolol Treatment for Infantile Hemangiomas" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 11: 3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113332

APA StyleKwak, J. H., Yang, A., Jung, H. L., Kim, H. J., Kim, D. S., Shim, J. Y., & Shim, J. W. (2024). Cardiac Evaluation before and after Oral Propranolol Treatment for Infantile Hemangiomas. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(11), 3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113332