Evaluating the Correlation between Myofascial Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Function: A Prospective Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Interventions

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simons, D.G. Clinical and Etiological Update of Myofascial Pain from Trigger Points. J. Musculoskelet. Pain. 1996, 4, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aredo, J.V.; Heyrana, K.J.; Karp, B.I.; Shah, J.P.; Stratton, P. Relating Chronic Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis to Signs of Sensitiza-tion and Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. Semin. Reprod. Med. Jan. 2017, 35, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, V.; Detterman, C.; Hallisey, A. Myofascial Pelvic Pain: An Overlooked and Treatable Cause of Chronic Pelvic Pain. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoni, B.; Sugumar, K.; Varacallo, M. Myofascial Pain. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535344/ (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Bedaiwy, M.; Patterson, B.; Mahajan, S. Prevalence of myofascial chronic pelvic pain and the effectiveness of pelvic floor physical therapy. J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 58, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Money, S. Pathophysiology of Trigger Points in Myofascial Pain Syndrome. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2017, 31, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bron, C.; Dommerholt, J.D. Etiology of Myofascial Trigger Points. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Nijs, J. Trigger point dry needling for the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: Current per-spectives within a pain neuroscience paradigm. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 1899–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central Sensitization: A Generator of Pain Hypersensitivity by Central Neural Plasticity. J. Pain 2009, 10, 895–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Nijs, J.; Cagnie, B.; Gerwin, R.D.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Valera-Calero, J.A.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Nociceptive Condition Comorbid with Neuropathic or Nociplastic Pain. Life 2023, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, M.; Owens, J. Physiology, Viscerosomatic Reflexes. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559218/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Jarrell, J. Endometriosis and Abdominal Myofascial Pain in Adults and Adolescents. Curr. Pain. Headache Rep. 2011, 15, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, E.A.; Katzman, W.B. Recognizing Myofascial Pelvic Pain in the Female Patient with Chronic Pelvic Pain. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 41, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dommerholt, J.; Bron, C.; Franssen, J. Myofascial Trigger Points: An Evidence-Informed Review. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2006, 14, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirzadeh, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Monteiro, S.; Grosman-Rimon, L.; Srbely, J.; Kumbhare, D. A Survey of Healthcare Practitioners on Myofascial Pain Criteria. Pain Pract. 2018, 18, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonder, J.H.; Chi, M.; Rispoli, L. Myofascial Pelvic Pain and Related Disorders. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 28, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, P.; Khachikyan, I.; Sinaii, N.; Ortiz, R.; Shah, J. Association of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis with signs of sensi-tization and myofascial pain. Obstet. Gynecol. März 2015, 125, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, V.T.; Stratton, P.; Tandon, H.K.; Sinaii, N.; Aredo, J.V.; Karp, B.I.; Merideth, M.A.; Shah, J.P. Widespread myofascial dysfunction and sensitisation in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaff, A.A.; D’Hooghe, T.M.; Dunselman, G.A.; Dirksen, C.D.; Hummelshoj, L.; WERF EndoCost Consortium; Simoens, S. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: Results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippl, A.L.; Reiser, E.; Seeber, B. Endometriosis and mental health disorders: Identification and treatment as part of a multi-modal approach. Fertil. Steril. März 2024, 121, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghmans, B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: An untapped resource. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.; Brown, J.; Heiman, S.; Leiblum, C.; Meston, R.; Shabsigh, D.; Ferguson, R.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex. Marital. Ther. Juni 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, M.R.; Sutcliffe, S.; Ghetti, C.; Chu, C.M.; Spitznagle, T.; Warren, D.K.; Lowder, J.L. Development of a standardized, reproducible screening examination for assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 255.e1–255.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Essential Elements of Universal Health Coverage. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/reproductive-health/uhl-technical-brief-srhr.pdf?sfvrsn=ceca4027_1&download=true (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Abbott, J.; Hawe, J.; Hunter, D.; Holmes, M.; Finn, P.; Garry, R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dückelmann, A.M.; Taube, E.; Abesadze, E.; Chiantera, V.; Sehouli, J.; Mechsner, S. When and how should peritoneal endometriosis be operated on in order to improve fertility rates and symptoms? The experience and outcomes of nearly 100 cases. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 304, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, C.J.; Ewen, S.P.; Whitelaw, N.; Haines, P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1994, 62, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velho, R.V.; Sehouli, J.; Mechsner, S. Mechanisms of peripheral sensitization in endometriosis patients with peritoneal lesions and acyclical pain. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1327–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.M.; Gattrell, W.T.; Gude, K.; Singh, S.S. Reevaluating response and failure of medical treatment of endometriosis: A systematic review. Fertil. Steril. Juli 2017, 108, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, N.L.; Huang, A.J.; Liu, Y.D.; Noga, H.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Williams, C.; Allaire, C.; Yong, P.J. Association of Central Sensitization Inventory Scores with Pain Outcomes after Endometriosis Surgery. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faubion, S.S.; Rullo, J.E. Sexual Dysfunction in Women: A Practical Approach. Am. Fam. Physician. 2015, 92, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Xu, H.; Zhang, T.; Gao, Y. Endometriosis decreases female sexual function and increases pain severity: A meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 307, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verit, F.F.; Verit, A.; Yeni, E. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction and associated risk factors in women with chronic pelvic pain: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2006, 274, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, J.P. Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Rev. Saude Publica 2022, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzichristou, D.; Kirana, P.S.; Banner, L.; Althof, S.E.; Lonnee-Hoffmann, R.A.; Dennerstein, L.; Rosen, R.C. Diagnosing sexual dysfunction in men and women: Sexual history taking and the role of symptom scales and questionnaires. J. Sex. Med. August 2016, 13, 1166–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | All Patients n = 83 | No MFPP n = 46 (55.4%) | MFPP * n = 37 (44.6%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.7 (27.2–41.2) | 32.9 (26.4–40.5) | 31.7 (27.5–43.7) | 0.700 |

| Height [cm] | 167 (163–170) | 167 (163–170) | 168 (163–172) | 0.422 |

| Weight [kg] | 61 (55.5–77.0) | 60.0 (55.8–76.5) | 67 (55.0–80.0) | 0.399 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 22.66 (20.7–27.1) | 21.9 (20.2–26.0) | 22.96 (20.8–27.82) | 0.618 |

| Gravidity | ||||

| 0 | 48 (57.8%) | 29 (63.0%) | 19 (51.4%) | 0.666 |

| 1 | 15 (18.1%) | 8 (17.4%) | 7 (18.9%) | |

| 2 | 9 (10.8%) | 5 (10.9%) | 4 (10.8%) | |

| 3 | 3 (3.6%) | 1 (2.2%) | 2 (5.4%) | |

| 4 | 6 (7.2%) | 3 (6.5%) | 3 (8.1%) | |

| 5 | 2 (2.4%) | 0 | 2 (5.4%) | |

| Paritys | ||||

| 0 | 55 (66.3%) | 30 (65.2%) | 25 (67.6%) | 0.799 |

| 1 | 13 (15.7%) | 9 (19.6%) | 4 (10.8%) | |

| 2 | 10 (12.0%) | 5 (10.9%) | 5 (13.5%) | |

| 3 | 3 (3.6%) | 1 (2.2%) | 2 (5.4%) | |

| 4 | 2 (2.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.7%) | |

| Confirmed endometriosis | ||||

| yes | 12 (14.5%) | 8 (17.4%) | 4 (10.8%) | 0.397 |

| no | 71 (85.5%) | 38 (82.6%) | 33 (89.2%) | |

| Desire to have children | ||||

| yes | 19 (22.9%) | 15 (32.6%) | 4 (10.8%) | 0.019 |

| no | 64 (77.1%) | 31 (67.4%) | 33 (89.2%) | |

| Hormonal therapy | ||||

| No | 62 (74.7%) | 36 (78.3%) | 26 (70.3%) | 0.405 |

| Yes | 21 (25.3%) | 10 (21.7%) | 11 (29.7%) | |

| Bleeding | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | 1 (2.7%) | 0.529 |

| Pain | 7 (8.4%) | 3 (6.5%) | 4 (10.8%) | |

| Pain + contraception | 4 (4.8%) | 1 (2.2%) | 3 (8.1%) | |

| HRT | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | 1 (2.7%) | |

| Contraception | 6 (7.2%) | 4 (8.7%) | 2 (5.4%) | |

| Other | 2 (2.4%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0 | |

| Menstrual cycle | ||||

| Amenorrhea | 9 (10.8%) | 4 (8.7%) | 5 (13.5%) | 0.508 |

| Regular cycle | 61 (73.5%) | 33 (71.7%) | 28 (75.7%) | |

| Irregular cycle | 13 (15.7%) | 9 (19.6%) | 4 (10.8%) | |

| Pain | ||||

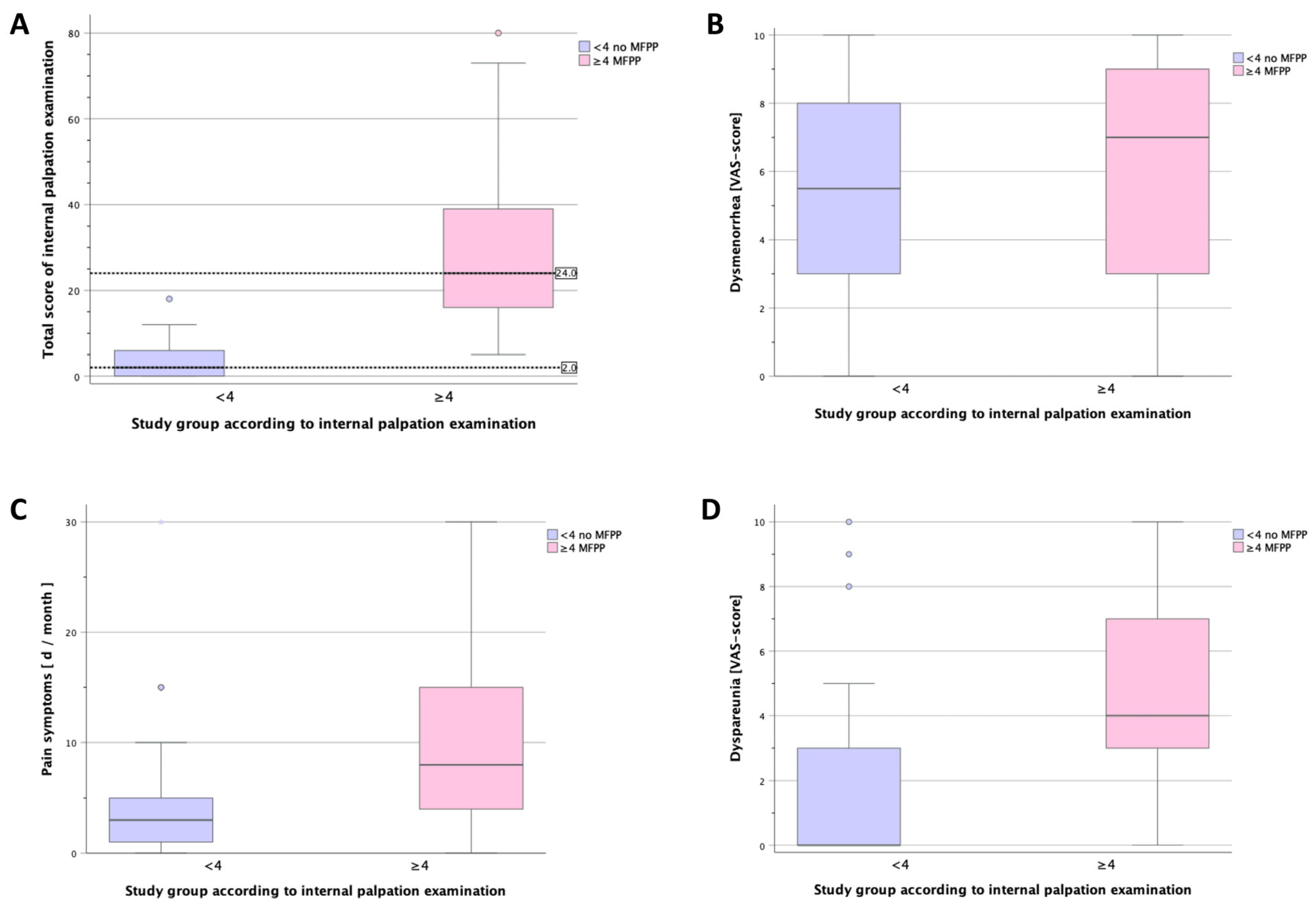

| Overall pain [days/month] | 5.0 (2.0–15) | 3 (1–5.5) | 8 (4–15) | 0.002 |

| Dysmenorrhea [VAS] | 7.0 (3.0–8.0) | 5.5 (2.8–8.0) | 7.0 (3.0–9.0) | 0.168 |

| Lower abdominal pain [VAS] | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0–4.0) | 0.094 |

| Dyspareunia [VAS] | 3.0 (0–5.0) | 0 (0–3.3) | 4 (3.0–7.0) | <0.001 |

| Dyschezia [VAS] | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0–3.0) | 0.392 |

| FSFI-d | 26 (20.2–29.5) | 28.3 (24.8–28.3) | 20.8 (18.9–26.4) | 0.089 |

| Internal palpation | 8 (1–23) | 2 (0–6.5) | 24 (15.0–40.5) | <0.001 |

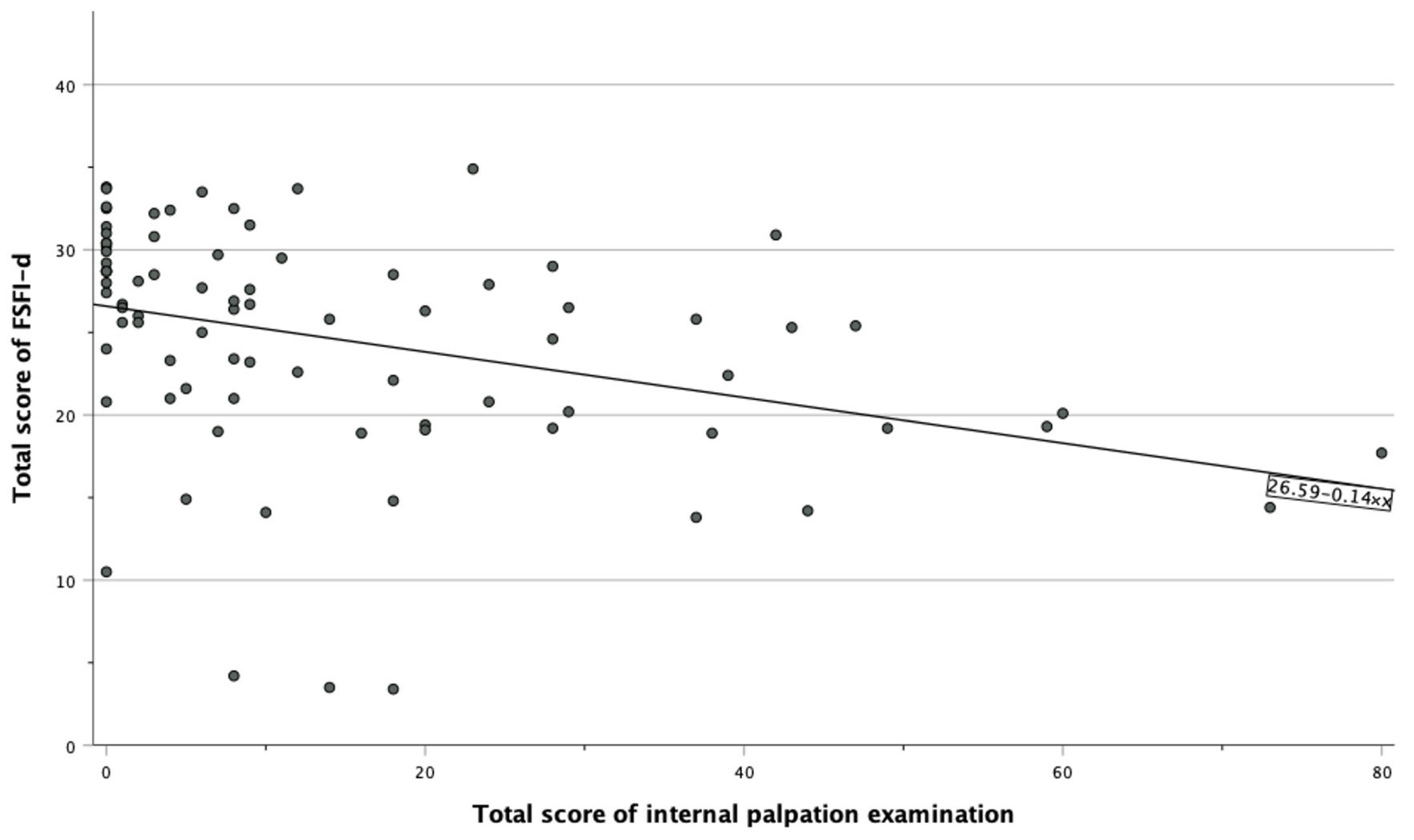

| r | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| FSFI-d subdomain | ||

| Desire | −0.22 | 0.045 |

| Arousal | −0.36 | <0.001 * |

| Lubrication | −0.23 | 0.005 * |

| Orgasm | −0.18 | 0.027 |

| Satisfaction | −0.18 | 0.028 |

| Pain | −0.36 | <0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sandrieser, L.; Heine, J.; Bekos, C.; Perricos-Hess, A.; Wenzl, R.; Husslein, H.; Kuessel, L. Evaluating the Correlation between Myofascial Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Function: A Prospective Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164604

Sandrieser L, Heine J, Bekos C, Perricos-Hess A, Wenzl R, Husslein H, Kuessel L. Evaluating the Correlation between Myofascial Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Function: A Prospective Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(16):4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164604

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandrieser, Lejla, Jana Heine, Christine Bekos, Alexandra Perricos-Hess, René Wenzl, Heinrich Husslein, and Lorenz Kuessel. 2024. "Evaluating the Correlation between Myofascial Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Function: A Prospective Pilot Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 16: 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164604

APA StyleSandrieser, L., Heine, J., Bekos, C., Perricos-Hess, A., Wenzl, R., Husslein, H., & Kuessel, L. (2024). Evaluating the Correlation between Myofascial Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Function: A Prospective Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(16), 4604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164604