Abstract

Metamizole, or dipyrone, has been used for decades as a non-narcotic analgesic, providing pain relief from musculoskeletal disorders and antipyretic and antispasmolytic properties. Despite being in use since the 1920s, its mechanism of action still needs to be discovered. Despite causing fewer adverse effects when compared to other analgesics, its harmful effects on the blood and lack of evidence regarding its teratogenicity make the usage of the drug questionable, which has led to it being removed from the drug market of various countries. This narrative review aims to provide a detailed insight into the mechanism of action and efficacy, comparing its effectiveness and safety with other classes of drugs and the safety profile of metamizole.

1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) continues to be the primary contributor to years lived with disability worldwide. In 2020, there were over 500 million prevalent cases of LBP globally. Although age-standardised rates have slightly declined over the past three decades, the projected scenario for 2050 is concerning because more than 800 million people are expected to suffer from LBP [1]. Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), including neck pain, were ranked subsequently at third and fourth positions, respectively [2]. MSDs, as per the definition of the World Health Organization, include health issues affecting the musculoskeletal system. MSDs include a broad spectrum ranging from slight discomfort to incapacitating injuries [3]. Sprains, strains, tears, soreness, pain, hernias, carpal tunnel syndrome, and connective tissue injuries are prevalent MSDs [4]. Musculoskeletal pain has a significant impact on the quality of life [5]. Chronic musculoskeletal pain disrupts daily life through sleep disruption, depressed mood, fatigue, and various other limitations [5].

Globally, MSDs are on the rise, posing significant challenges in interventions and resource allocation [6]. Although MSDs impact various age groups, their prevalence notably rises with age. In those over 65, around three out of four individuals suffer from MSDs [7]. From 1996–1998 to 2009–2011, the incidence of MSDs surged by 19%, reaching 102.5 million cases [8]. Economic burdens in the same period skyrocketed from USD 367.1 billion to USD 796.3 billion, a 117% increase. In lower middle-income countries (Tanzania), the rise in those with MSDs proves to be a burden, because over 10% of the income is allocated to treating the disorders, which is often 2–3 times the usual medical expense [9]. With over 88.8% of the patients earning less than USD 250, 73.7% stated that healthcare expenses were a catastrophic burden [10]. Economic burden (for RA) in direct costs (mainly drugs, comprising about 87% of the expenditure) range from USD 401 to USD 67,306, and indirect costs such as absenteeism and work disability account for 39% to 86% of the costs, ranging from USD 509 to USD 22,444 [11].

Additionally, post-injury disability led to 47% of patients being unable to return to full employment [12]. Furthermore, patients also reported a decrease in individual and familial wages in 88% and 33% of injuries, respectively, and intra-family labour reallocation in 83% of the injuries [13,14]. Non-pharmacological approaches such as self-management, education, exercise, and psychosocial interventions play a pivotal role in pain management [4]. Exercise and psychosocial modalities, particularly aerobic and resistance exercises, show benefits [15,16]. Complementary treatments, such as acupuncture, can be effective [17]. Pharmacological interventions, which include analgesics and corticosteroid injections, aim for short-term relief [16,18]. NSAIDs and opioids, although showing modest effects, carry risks for potential adverse effects such as sedation and mood swings [16]. Photo biomodulation therapy, using light, has emerged as a novel approach to pain management [18].

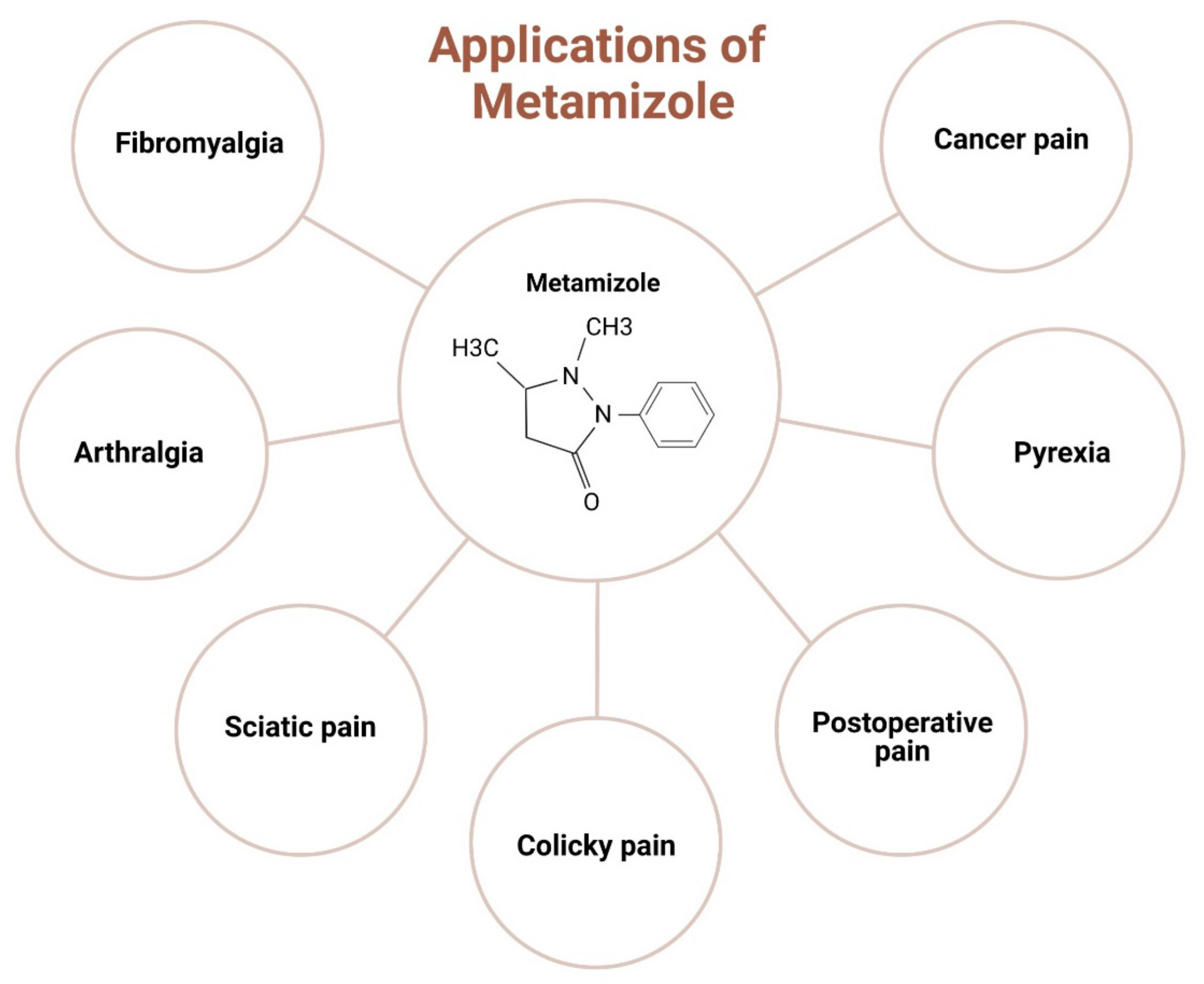

Metamizole, a pyrazolone derivative and non-opioid analgesic with the N02BB02 Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code, has been used since 1922 primarily for pain relief, fever reduction, and antispasmodic effects [19,20,21]. The chemical formula of the drug is N-(2,3-dimethyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-3-pyrazolin-4-yl) [22]. Various studies support its efficacy in managing pain with different origins and intensities, such as postoperative pain, cancer pain, headaches, and migraines. Notably, it demonstrates safety in short-term use with adverse effects on the lower gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal, and neurological systems [19]. Initially considered a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, metamizole was later reclassified as a non-narcotic analgesic given its inhibitory action on central cyclooxygenase(COX)-3 [22]. There are numerous reviews stating the efficacy of the drug, often claiming it to be similar or superior to NSAIDs in some instances [23,24]. Although concerns have been previously raised on agranulocytosis caused by the drug, a previous study [25] showed the incidence to be lesser than more commonly administered medications such as antithyroid drugs and ticlopidine. The event of mild adverse effects was also lesser in those taking metamizole when compared to other non-opioid analgesics [26]. Reviews have also previously been conducted on the efficacy of the drug when combined with other non-opioid analgesics. However, it is to be noted that all previous reviews focused singularly on one particular aspect of the drug [27,28], and no review focused on the overall efficacy of the drug across various causes of musculoskeletal disorders.

In recent years, several comprehensive reviews have examined metamizole’s role in managing musculoskeletal disorders, providing valuable insights into its efficacy, safety, and pharmacological profile. These reviews have explored its pharmacological mechanisms, including its effects on COX-3 inhibition and potential interactions with cannabinoid and opioidergic systems. They have also confirmed its efficacy in various pain conditions, compared its effectiveness with other analgesics, and addressed ongoing safety concerns, particularly regarding agranulocytosis [29]. Despite these contributions, there remains a need for a holistic review that synthesises these findings across the spectrum of musculoskeletal disorders, considering both its therapeutic potential and safety profile in diverse clinical contexts.

The review aims to summarise the efficacy and safety profile of metamizole drugs in treating various musculoskeletal disorders. This review introduces the pharmacology of the drug, followed by clinical indications and evidence of the drug efficacy, safety profile, comparative analysis with other opioid and non-opioid analgesics, various challenges associated with current research on the drug, and concluding with possible unexplored aspects of the drug that may solidify its role in treating multiple demographics of the population.

2. Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science to identify studies on the efficacy and safety of metamizole in managing musculoskeletal disorders. The search strategy included keywords and MeSH terms such as “Metamizole”, “Dipyrone”, “musculoskeletal disorders”, “analgesia”, “pain management”, “efficacy”, “safety”, and “adverse effects”. Inclusion criteria were studies involving metamizole for treating musculoskeletal disorders, published in English, involving human subjects, and including randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, and systematic reviews that reported on the efficacy, safety, and adverse effects of metamizole. Exclusion criteria were studies unrelated to metamizole, animal studies, articles not available in English, studies with insufficient data on outcomes, conference abstracts, editorials, and commentaries.

3. Pharmacology of Metamizole

Metamizole, represented by the chemical formula N-(2,3-dimethyl-5-oxo-1-phenyl-3-pyrazolin-4-yl), is a prodrug that spontaneously undergoes breakdown in an aqueous environment [22]. The drug is usually a white or a crystalline white powder that is very soluble in water and alcohol [30]. Pyrazolone derivatives, with their nearly neutral pKa value and minimal plasma protein binding, exhibit a homogeneous and rapid distribution throughout the body. This efficient dispersion is attributed to their exceptional ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier easily [31]. Administered intravenously, the parent drug is detectable in the bloodstream for approximately 15 min, while oral administration results in its absence in plasma and urine [22]. Orally ingested, metamizole is non-enzymatically hydrolysed in gastric juice to produce 4-methyl-amino-antipyrine (MAA) with an 85% bioavailability. In the liver, cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 further metabolises MAA into 4-formyl-amino-antipyrine (an end metabolite) and 4-amino-antipyrine (AA), the latter being acetylated into 4-acetyl-amino-antipyrine (AAA). AA and MAA transform into Arachidonoyl amides, penetrating the blood–brain barrier and reaching effective concentrations in the spinal cord to produce therapeutic effects [20,22]. Metamizole is commonly used to relieve visceral and somatic pain. Despite indications of its potential, it has not been employed for neuropathic pain [32].

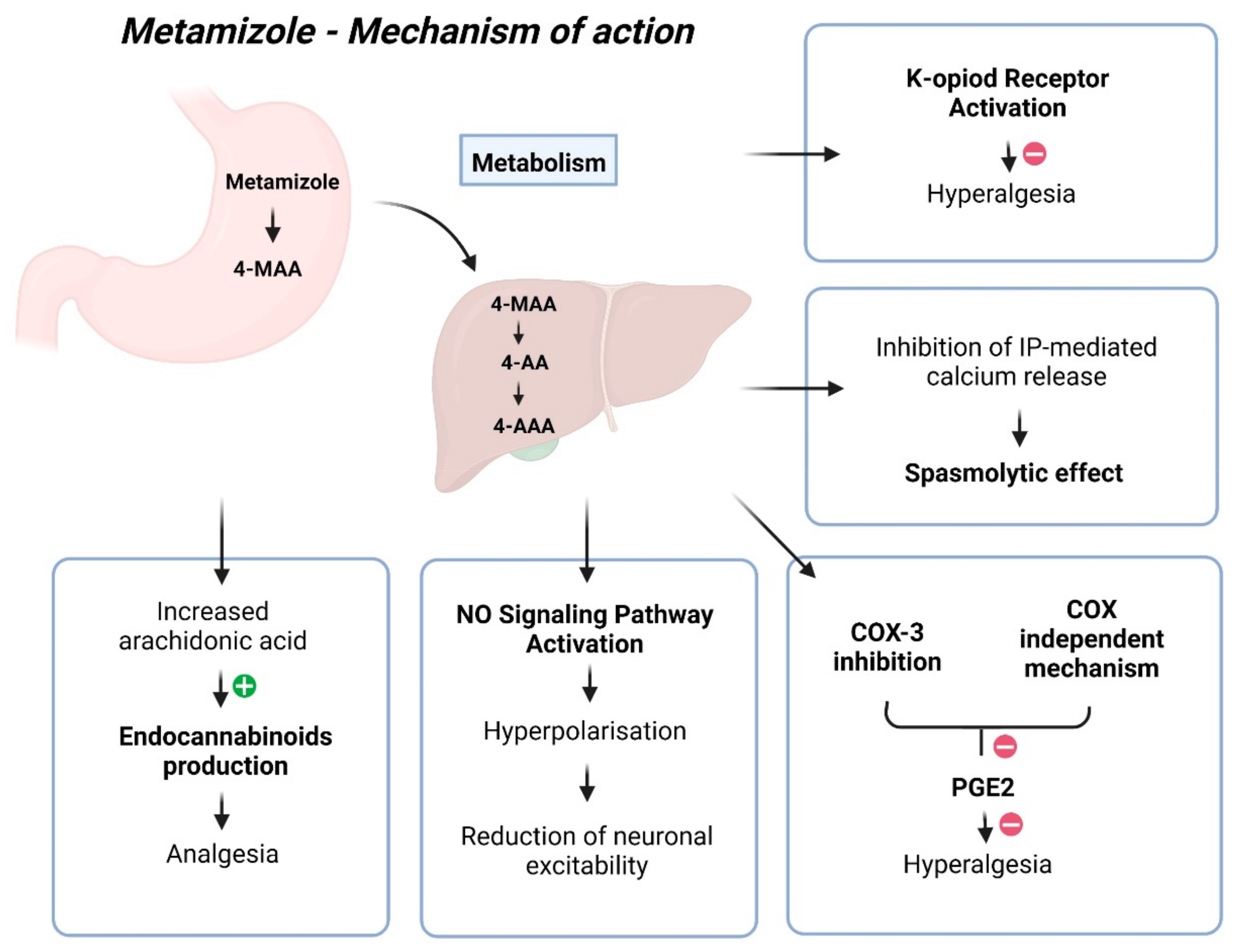

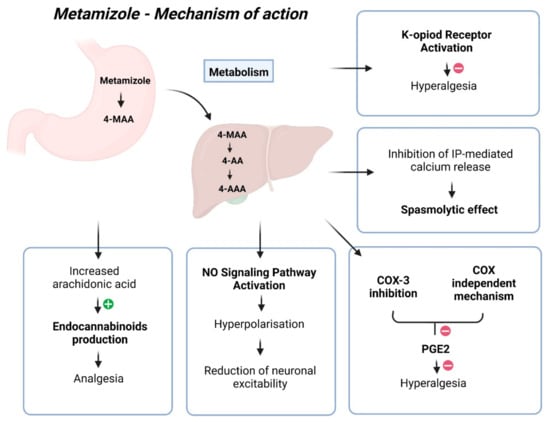

Despite more than 90 years of use, the mechanism of action for metamizole remains unclear, with its mechanism of analgesia being quite complex (Figure 1) [22]. The most probable explanation involves its impact on COX-3, the cannabinoid system, and the opioidergic system [22]. COX-3 retardation leads to reduced Prostaglandin E2 synthesis, diminishing nociceptor sensitivity and excitability, thereby achieving an analgesic effect [22]. However, the analgesic effect of metamizole is not associated with its capacity to inhibit prostaglandins [31]. The pharmacologically active metabolites of metamizole, MAA, and AA differ from classical COX inhibitors because they do not inhibit COX activity in vitro. Instead, they redirect prostaglandin synthesis, eliminating the possibility of COX inhibition through binding to its active site [33]. Many authors have emphasised the inhibition of COX activity as the primary mechanism of action for metamizole, with its action on COX-2 being tenfold more potent than COX-1 [34]. However, findings suggest that metamizole metabolites can directly impede hyperalgesia induced by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and isoprenaline through a COX-independent mechanism. Like paracetamol, metamizole exhibits COX inhibition activity in vitro, mainly targeting COX-2, yet demonstrates weak anti-inflammatory properties and minimal gastrointestinal toxicity in humans [35]. Reducing prostaglandin synthesis inhibits pain-related signals and increases the availability of arachidonic acid to produce endocannabinoids, which exert analgesic effects in the spinal cord [30]. Previous investigations have reported that metamizole inhibits prostaglandin formation, deduced by assessing PGF2a and two primary urinary metabolites of prostacyclin [36,37,38,39,40]. The pharmaceutical compound exhibits specific anti-inflammatory properties, albeit to a lesser extent when juxtaposed with alternative medications, potentially attributed to its diminished affinity for COX in environments characterised by elevated peroxide levels, such as inflamed tissues [21].

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of metamizole.

Other potential mechanisms include the agonistic effect of metamizole on type 1 CB1 cannabinoid receptors, reducing GABAergic transmission in the periaqueductal grey matter. This mainly disinhibits glutaminergic activating neurons, activating the descending pathway, resulting in antinociception. Additionally, the analgesic effect of metamizole may activate the endogenous opioidergic system [22]. The drug may also directly hinder nociceptor sensitisation by activating the NO signalling pathway. The authors hypothesised that metamizole facilitates activation of the PI3Kγ/AKT/nNOS/cGMP pathway, leading to the hyperpolarisation of primary sensory neuron terminals and a subsequent reduction in neuronal excitability [41]. Additional studies have found that the anti-hyperalgesic effect of 4-MAA relies on κ-opioid receptor activation, functioning similarly to a morphine-like drug [35]. Another likely mechanism involves the delayed initiation of the l-arginine/NO/cGMP/K+ channel pathway in the periphery and the spinal cord [30]. Metamizole induces the relaxation of G protein–coupled receptor-mediated contractions in isolated guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. The observed metamizole-induced reduction in ATP-triggered intracellular free calcium levels and the inhibition of GPCR-stimulated inositol phosphate accumulation suggest that the mechanism underlying its spasmolytic effect may potentially involve inhibiting IP-mediated calcium release from intracellular stores [42].

4. Clinical Evidence

4.1. Fibromyalgia

In a cross-sectional study on 156 patients with fibromyalgia (144 women and 12 men), the prevalent use of NSAIDs and metamizole provided maximal pain relief, which underscored the necessity for further randomised control studies to evaluate drug efficacy [43]. Limitations encompass recall bias, uneven drug distribution, non-compliance, overlapping medications, and placebo-related uncertainties.

4.2. Arthralgia

Brito et al.’s review [44] focused on managing mild and moderate arthralgia caused by Chikungunya. Metamizole and paracetamol were frequently employed as monotherapy, with constant monitoring of adverse effects considered unnecessary in standard dosing. A case report on the management of a pregnant patient with type I osteogenesis imperfecta using quantitative ultrasonometry stated that at 31 weeks and 2 days of gestation, in addition to physiotherapy, only metamizole was successful in alleviating the patient’s pain, with the patient’s mobility being adequate [45].

4.3. Management of Acute and Chronic Pain

In a survey involving German anaesthesiologists and pain physicians, responses from 2237 participants revealed that 93.8% used metamizole for acute pain, and 76.7% used oral metamizole combined with other non-opioid analgesics for chronic pain [46]. Agranulocytosis occurred in 3.5% and 1.5% of respondents in acute and chronic pain management, respectively [46]. Limitations include the absence of specific patient numbers and information on severe side effects [46]. A cohort study on the use of tramadol and other analgesics as a risk factor for opioid use in 12,783 patients who were treated for pain stated that metamizole was the most frequent drug used and those who received tramadol were at risk of receiving opioids within 12 months [47]. The analgesic effects of metamizole and NSAIDs were similar. Limitations of the study included lack of access to medical records to verify indications to use different analgesics, the possibility of residual confounders, inability to assess whether the drug was brought from outside the health system, and use of psychoactive substances by the patient. A study comparing the tolerance of metamizole and morphine in 16 patients with acute pancreatitis showed faster onset of pain relief in those taking metamizole, with 75% of the patients attaining pain relief compared to 37.5% of those taking morphine [48]. In the end, 75% and 50% of the patients taking metamizole and morphine achieved pain relief, respectively [48].

4.4. Sciatic Pain

A multicentre observer-blind randomised trial [49] enrolled 260 patients with low back or sciatic pain. Metamizole administration resulted in significant pain reduction compared to diclofenac or placebo. Adverse reactions were most prevalent in the metamizole group (5%), compared to diclofenac (1%) and placebo (2%). An experimental study [32] on the effect of intraperitoneal administration of metamizole in relieving pain from chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve in Wistar rats showed a diminished development of neuropathic pain by reduced expression of pronociceptive interleukins.

4.5. Colicky Pain

A double-blind, double-dummy randomised controlled clinical trial [50] compared the analgesic effect of 1 or 2 g metamizole and 75 mg of sodium diclofenac administered intramuscularly or intravenously in 293 patients. Metamizole 2 g intramuscular demonstrated a superior analgesic effect from 60 min to 6 h than metamizole 1 g and sodium diclofenac 75 mg. The analgesic effect of metamizole 2 g intravenous was higher than intramuscular, with the effect starting at 10 and 20 min. Pain relief was proportionately higher in metamizole, with 2 g intravenous showing the most significant reduction in pain. A clinical pilot study [51] comparing the analgesic effects of cizolirtine citrate and metamizole sodium in 64 patients aged 18–65 with haematuria and moderate-to-severe pain showed a quicker onset of pain relief in those taking metamizole. A mean decrease of pain scores by 69.1% was observed in those taking metamizole compared with a 57.2% decrease in those taking cizolirtine citrate. At the 30-min mark, 56.3% stated complete, and 75% stated satisfactory pain relief, with fewer taking rescue medication when administered with metamizole. A limitation of the study is the lack of internal sensitivity measurement; hence, sensitivity to treatment differences was not ensured. A multicentre double-blind, randomised control parallel-group trial [52] comparing the efficacy of intravenous bolus of dexketoprofen trometamol and intravenous infusion of metamizole in 308 patients with moderate-to-severe pain caused by renal colic reported similar total pain relief scores (TOTPAR) scores to be identical in metamizole (15.5 ± 8.6) and dexketoprofen 50 mg (15.3 ± 8.6) and higher than dexketoprofen 25 mg (13.5 ± 8.6) with faster effects of analgesia occurring in those taking dexketoprofen with the efficacy between the two drugs being similar.

4.6. Postoperative Pain

In a prospective, placebo-controlled, randomised, double-blind trial [53] comparing the effects of intravenous 1 g metamizole, 1 g paracetamol, 8 mg lornoxicam, and 0.9% isotonic saline (placebo) on postoperative pain control and morphine consumption after lumbar disc surgery in 80 patients, pain reduction was observed in those administered metamizole and paracetamol. Still, it was less in those administered lornoxicam. ANOVA measures revealed that pain scores were significantly lower in metamizole than in lornoxicam. Limitations of the study included pain assessment only at rest, discharged 1 day after the procedure, and categorical evaluation of side effects not used to detect adverse effects caused by metamizole. In a double-blinded randomised control trial [54] assessing the analgesic effect of 500 mg metamizole and 500 mg aspirin in postoperative orthopaedic patients (281 patients), pain relief starting at 30 min after drug administration up to 6 h favoured metamizole over aspirin. Gastrointestinal side effects of metamizole were far less than those of aspirin.

In a prospective, randomised, double-blinded study of tramadol, metamizole, and paracetamol [55], assessing postoperative analgesia at home after ambulatory hand surgery in 120 patients, the number of patients requiring supplementary analgesics was 23% with tramadol, 31% with metamizole, and 42% with paracetamol. Those receiving metamizole and paracetamol had reasonable analgesia rates of 70% and 60%. Metamizole provided adequate analgesia for 69% of patients on day 1 and 85% on day 2. In a prospective, double-blinded, randomised study [56] on the management of postoperative pain after total hip arthroplasty, comparing the effects of metamizole and paracetamol on 110 patients, the mean values of pain AUC were 17.9 for metamizole and 30.6 for paracetamol during the first 24 h in the postoperative period with metamizole showing better pain control in the first 24 h. The limitation of the study is using a visual analogue scale (VAS) to measure pain, because various psychological and other factors influence it. A randomised, double-blind study [57] comparing the efficacy of intravenous paracetamol (1 g every 6 h) to metamizole (1 g every 6 h) and parecoxib (40 mg every 12 h) for postoperative pain relief after minor-to-intermediate surgery conducted on 196 patients, with patient-controlled piritramide as the rescue medication, showed a significant and quicker onset decrease in VAS pain scores on that administered metamizole. A lesser proportion of patients needed rescue medication, and the duration of the administration of metamizole and rescue medication was longer.

A double-blind, randomised controlled trial [58] reporting the mean difference in the pain score between metamizole, paracetamol, and ibuprofen found non-inferiority between the three drugs. However, the intake of rescue medication was higher in those taking an ibuprofen–paracetamol combination on POD 2. The study suggested metamizole as a valuable alternative to ibuprofen, especially in those with contraindications to NSAIDs. Limitations of the study included a lack of firm conclusions about medical safety, intake of tramadol at home by patients was significantly higher than the control group, rigorous exclusion criteria considerably reduced the sample size, and four different types of surgery were included that may all have various pain trajectories.

4.7. Pyrexia

In an open non-comparative study [59], 100 children (51 male, 49 female) aged 3 months–12 years, with an oral temperature of 38.5 degrees Celsius and complaints of pain from various causes, were given metamizole 10–15 mg/kg 6 to 8 hourly for 3 days. Of those with pain, 57% responded well and 43% responded satisfactorily to the drug. In those with fever, 66.7% showed a good response, 25.8% showed a satisfactory response, and 7.5% showed an unsatisfactory response.

4.8. Cancer Pain

In a double-blind, randomised parallel clinical trial [60] comparing the efficacy and tolerance of oral metamizole and morphine in 121 patients, the degree of pain relief using the 100 mm VAS showed comparable pain relief between those administered 2 g of metamizole and 10 mg of morphine. More patients had better tolerance and fewer side effects when taking metamizole. However, the onset of pain relief was faster in patients administered morphine.

4.9. Experimental Pain

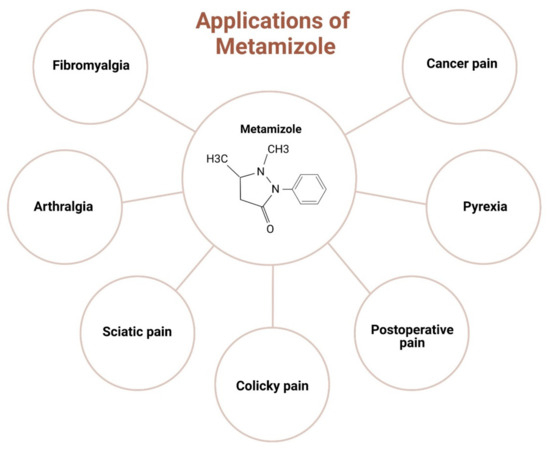

A randomised double-blind, parallel-group pre-test-post-test study [61] on the effect of tilidine and metamizole on cold pressor pain conducted in 264 healthy volunteers showed a lower AUPC% and higher pain tolerance compared with low-dose opioids, with fewer side effects than other drugs. A recent study [58] on 10 healthy volunteers (4 females and 6 males) comparing the analgesic efficacy of metamizole and tramadol in experimental pain showed the efficacy of tramadol to be much higher than metamizole, with the relative potencies of metamizole and tramadol assessed to be 1:23. However, no side effects were reported after the intake of metamizole. The clinical studies of metamizole are tabulated in Table 1. The clinical application of metamizole in orthopaedics is depicted in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Clinical studies of metamizole.

Figure 2.

Clinical applications of metamizole in orthopaedics.

5. Efficacy of Metamizole

With its role in various proposed pathways, metamizole affects antinociception, antipyretic analgesia, and antispasmolytic effects. The efficacy of the drug indicates a strong correlation between the dose of the drug and the onset of the action, duration, and degree of pain relief. Metamizole has also proved to be quite effective, with incidences of drug withdrawal being lower than other drugs of similar efficacy. In a comparative study [55] exploring the analgesic efficacy of tramadol, metamizole, and paracetamol, 81% of study subjects on day 1 and 82% on day 2 deemed the drug effective in providing pain relief following ambulatory hand surgery, with a satisfaction rate of 59% in individuals administered metamizole. Dose-dependent analgesic effects were identified, indicating that subjects receiving 15 mg of metamizole consumed 3.85 mg of morphine.

In comparison, those administered 40 mg of metamizole consumed only 2.55 mg of morphine, thus potentially minimising the adverse effects associated with morphine [62]. In adult acute renal colic, where analgesics such as cizolirtine citrate or metamizole sodium were employed, a swift onset of pain relief was particularly evident with metamizole. Notably, a mean decrease in pain scores by 69.1% was observed, and at the 30-min mark, 56.3% of patients reported complete pain relief, with 75% expressing satisfactory pain relief. Additionally, fewer individuals required rescue medication when metamizole was administered [51]. The role of metamizole in postoperative pain management following total hip arthroplasty showcased its potent efficacy, with lower pain scores recorded on the VAS, indicating a mean pain value of 17.9. Patients receiving metamizole also required a lower dose of morphine [56].

In treating lower third molar surgery, administering 2 g metamizole significantly reduces VAS pain scores starting from 15 min. At the 60-min mark, a notable percentage of patients achieved a 50% reduction in their basal VAS scores. The therapeutic effect was reported as “excellent” in 50.7% of patients and 41.7% of physicians, with a higher percentage of patients experiencing at least a one-grade improvement in verbal ratings compared to baseline values [63]. Metamizole’s effectiveness in managing pain post minor-to-intermediate surgeries was also evident, indicating a substantial reduction in pain scores [56]. Cancer patients receiving oral metamizole at a dosage of 2 g demonstrated a marked decrease in baseline VAS pain scores from 81.8 ± 0.6 to 34.9 ± 25.8 within 7 days, with the most significant pain improvement observed in the metamizole 2 g group by the fifth day [60]. A reduction focusing on oral metamizole monotherapy revealed that the number needed to treat to achieve a 50% reduction in pain after minor surgeries was 2.1 for metamizole 500 mg, showcasing its superior efficacy compared to other drugs [66].

In individuals treated with 800 mg of metamizole for cold pressor pain, a significantly lower area percentage under pain curve (%AUPC) ratings and higher pain tolerance were observed compared to low-dose opioid and control groups [61]. An ANOVA comparison between metamizole, paracetamol, and lornoxicam indicated significantly lower pain scores in those treated with metamizole post-lumbar disc surgery [53]. From the above studies, it is inferred that metamizole effectively manages pain and pyrexia. In most cases, patients were provided with satisfactory and good pain relief with the early start of its analgesic effects. It provided the patients with almost seamless postoperative analgesia in a few cases. Metamizole also reduces the unpleasant side effects of narcotic drugs and the need for rescue medications that some patients have to take to cope with the pain, one of the critical features highlighting the drug in a positive light. Early relief from pain also helps the patient return to their earlier lifestyle effortlessly. The efficacy of metamizole in the published literature is tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Efficacy of metamizole in published literature.

6. Safety Profile of Metamizole

Despite providing effective pain relief from musculoskeletal disorders, metamizole faced withdrawal from the markets in several countries, including the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, Sweden, Denmark, and India, following ongoing safety debates [57]. Notably, when administered in appropriate doses, it exhibits fewer gastrointestinal and renal side effects; however, instances of agranulocytosis, neutropenia, and various blood disorders have been reported [57]. Categorised as a Category B drug capable of inducing drug-induced liver injury, metamizole raised concerns with 40 reported incidents globally [67,68]. Cases of metamizole-induced liver injury revealed findings such as low-grade fibrosis (29%) and extensive centrilobular necrosis (35%) [68]. A database search identified 143 reports on liver-related side effects associated with metamizole, with the three leading causes being hepatic failure, drug-induced liver injury, and jaundice [68].

Among the most severe complications tied to metamizole are agranulocytosis and anaphylactic shock. Combined use with drugs such as methotrexate increases the risk of agranulocytosis [19,69]. First detected in 1935, agranulocytosis linked to dipyrone raises concerns, given its structural similarity to aminopyrine, a previously discontinued analgesia associated with increased agranulocytosis rates [70]. Reports indicate agranulocytosis after administering a test dose [71], highlighting immediate cell destruction in internalised individuals [72]. Factors related to agranulocytosis include the history of using a new medication or change in the previous medication, exposure to chemical or physical agents recently, or a recent bacterial or viral infection [71]. Prognosis is often decreased by age over 65 years, neutrophil count at diagnosis less than <0.1 × 109/L, presenting with severe deep infections or septicaemia or septic shock, and underlying disease or severe comorbidity. However, with appropriate management, mortality from idiosyncratic drug reactions stands at approximately 5% [73]. Agranulocytosis can also be successfully treated with recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factors [74].

Extended use of metamizole may induce renal toxicity, with allergy-related manifestations such as skin rashes and asthma. Risk factors include intolerance to metamizole, other non-opioids, and existing bronchial asthma. Notably, the incidence of agranulocytosis is minimal in patients concurrently receiving antibiotics [69]. In Europe, the annual incidence of drug-induced agranulocytosis ranges from 3.4 to 5.3 cases per million population, while in the USA, it is between 2.4 and 15.4 cases per million per year [69]. The drug’s impact on bone marrow, leading to blood dyscrasias such as leukopenia and aplastic anaemia, involves genetic mechanisms, with incidence variations in different geographical regions [69,75]. Complications such as angioedema and urticaria induced by pyrazolone derivatives may stem from a pseudo-allergic reaction, likely occurring via COX inhibition. Severe outcomes include Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis [69,76]. While rare, reports of acute kidney injury associated with metamizole exist, with a generally reduced prognosis compared to NSAIDs’ impact on the kidneys. The drug’s role in obstructive reactions leading to asthma attacks in allergic individuals involves the production of cysteinyl leukotrienes [69].

Metamizole, despite its potential toxicity, appears less harmful compared to NSAIDs. Unlike NSAIDs, which exhibit various side effects involving the gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular systems, metamizole, with its mechanism redirecting prostaglandin synthesis, demonstrates a protective effect on the gastric mucosa [77,78]. NSAIDs’ inhibition of COX 1-mediated generation of cytoprotective prostanoids like PGE2 and PGI2 contributes to their adverse effects [79]. Previous evidence highlighted significant renal risks and arrhythmias associated with NSAIDs, particularly rofecoxib, with effects intensifying with a higher dosage and a longer duration [77]. Another meta-analysis reported increased hypertension incidence with COXIBs compared to non-selective NSAIDs [80]. Studies on celecoxib underscore the elevated risk of cardiovascular complications, indicating a dose-related response to toxicity [81,82]. Paracetamol, while commonly used, has raised concerns regarding its impact on neurodevelopment. Observational studies have demonstrated a correlation between paracetamol use and neurodevelopmental disorders when taken for an extended duration during pregnancy. Issues related to gross motor development, communication, externalising and internalising behaviours, higher activity levels, hyperkinetic disorder, and the occurrence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) by age seven have been identified [36,83]. These findings highlight the need for careful consideration when prescribing paracetamol during pregnancy and suggest a potential link between its prolonged use and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children.

In contrast to NSAIDs, metamizole’s complications, primarily involving agranulocytosis, various allergic reactions, and liver toxicity, position it as a comparatively less toxic option [69]. Observational and cross-sectional studies suggest a correlation between paracetamol use and asthma diagnosis or exacerbations, raising concerns about its safety, particularly during pregnancy [84,85,86]. When considering and comparing the reporting odds ratio (ROR) between metamizole and NSAIDs in gastric or duodenal ulcers, metamizole showed an ROR of [95% CI]: 0.9 [0.7–1.2] when compared to non-selective NSAIDs (ROR [95% CI] ibuprofen 8.3 [7.8–8.7], naproxen 10.7 [10.2–11.1], and diclofenac 14.3 [13.8–14.9]) and in selective NSAIDs (celecoxib 6.9 [6.5–7.3], etoricoxib 7.2 [6.4–8.2]). However, there is a slightly increased risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in metamizole (ROR [95% CI] 1.5 [1.3–1.7]), which is still lower when compared to non-selective NSAIDs (ROR [95% CI] ibuprofen 8.2 [8.0–8.5], naproxen 7.9 [7.7–8.1], and diclofenac 9.1 [8.8–9.3]) and non-selective NSAIDs (ROR celecoxib 5.9 [5.7–6.1] and etoricoxib 5.8 [5.2–6.4]). When comparing the significance of renal impairment, it was also lesser in those taking metamizole (ROR [CI 95%] 1.2 [1.0–1.3]) when compared to NSAIDS (ROR [CI 95%] ibuprofen 2.4 [2.3–2.5], diclofenac 2.3 [2.2–2.4], celecoxib 2.1 [2.0–2.2], etoricoxib 1.9 [1.7–2.2]). When comparing the cardiovascular effects between the two, metamizole showed an ROR of [CI 95%] 0.5 [0.4–0.5] when compared to selective COX 2 inhibitors (ROR [CI 95%] for celecoxib 8.5 [8.3–8.7] and etoricoxib 1.9 [1.7–2.2]) [24]. When comparing metamizole with paracetamol, the risk ratio (95% CI) between the two for adverse effects was 1.08 (0.69,1.68) and dropped out due to adverse effects was 1.47 (0.32,6.75), pain at the site of injection was 0.50 (0.14–0.79), nausea was 1.17 (0.74–1.6), vomiting was 0.74 (0.34–1.62), exclusively blood dyscrasias was 2 (0.20–20.33), cardiovascular effects was 3.48 (1.07–11.27), neurological effects was 0.63 (0.08,4.94) and dermatologic–l conditions was1.44 (0.24,8.55) [87]. The side effects overall are lesser in those taking metamizole.

7. Comparative Investigations

A study systematically compared the analgesic effect of tramadol, metamizole, and paracetamol which indicated that 81% of study subjects on day 1 and 82% on day 2, compared to 52% on day 1 and 2 in those taking tramadol, perceived metamizole as providing adequate pain relief following ambulatory hand surgery. Notably, 59% of patients expressed satisfaction with metamizole compared to only 47% of those taking tramadol [55]. In adult acute renal colic cases, the onset of pain relief was notably quicker with metamizole. There was a 69.1% and 57.2% decrease in the VAS pain score intensity in those taking metamizole and cizolirtine citrate, respectively. At the 30-min mark, in those taking metamizole and cizolirtine citrate, respectively, 56.3% and 48.4% expressed complete pain relief, and 75% and 64.5% expressed satisfactory pain relief [51]. Patients undergoing postoperative pain management after total hip arthroplasty demonstrated reduced outcomes, with reduced morphine consumption and lower pain scores of 17.9 in those taking metamizole when compared to a score of 30.6 in those taking paracetamol. This suggests the drug’s potential as an effective analgesic in orthopaedic surgery [56]. The use of 2 g of metamizole in lower third molar surgery revealed significant reductions in VAS pain scores starting as early as 15 min after administration, with a decrease in pain by 37.3% in those taking 2 g of metamizole when compared to a 20.9% decrease in those taking ibuprofen. This was further supported by a higher percentage of patients experiencing a meaningful reduction in pain, underlining the drug’s rapid onset and efficacy in this specific surgical procedure [3]. After minor-to-intermediate surgery, metamizole exhibited a significant decrease in pain scores compared to other analgesic groups. Scores after 1 week were 7.1 and 12.2, and the values of associated pain were documented to be 5.6 and 12.4 in metamizole and parecoxib, respectively [56].

Treatment of cancer pain indicated a decrease in baseline VAS pain scores from 81.8 ± 0.6 to 34.9 ± 25.8 in 7 days, with the highest pain improvement in the metamizole 2 g group by the fifth day. However, a slight difference was found in those taking metamizole 2 g and morphine. However, this difference was not statistically significant [60]. Patients treated with 800 mg of metamizole for cold pressor pain experienced slightly lower area percentage under the pain curve (%AUPC) ratings and a higher pain tolerance compared to low-dose opioid and control groups (59.7 ± 26.0, 71.1 ± 22.4, 62.1 ± 24.7), further substantiating its efficacy in experimental pain settings [61]. ANOVA scores comparing metamizole, paracetamol, and lornoxicam revealed significantly lower pain scores in individuals administered metamizole post-lumbar disc surgery [53]. However, other experiments have shown that lornoxicam is non-inferior compared to other drugs. The need for rescue medication was elevated in those taking lornoxicam [88].

Metamizole’s efficacy is evident in reducing pain scores across multiple studies, highlighting its role in diverse clinical contexts. Findings from various studies indicate increased incidences of gastrointestinal side effects in patients taking NSAIDs, morphine, and tramadol, and increased bilirubin values were found in those taking cizolirtine citrate. Tiredness and sleepiness were found in patients taking metamizole. Syncope occurred in those taking ibuprofen. While some studies emphasise the economic advantage of metamizole over other analgesics, concerns about safety, including agranulocytosis risk, require careful consideration—the multifaceted evidence positions metamizole as a valuable analgesic option, especially in specific clinical scenarios. The comparative analysis of metamizole with other drugs is tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of comparative investigations.

8. Challenges and Future Directions

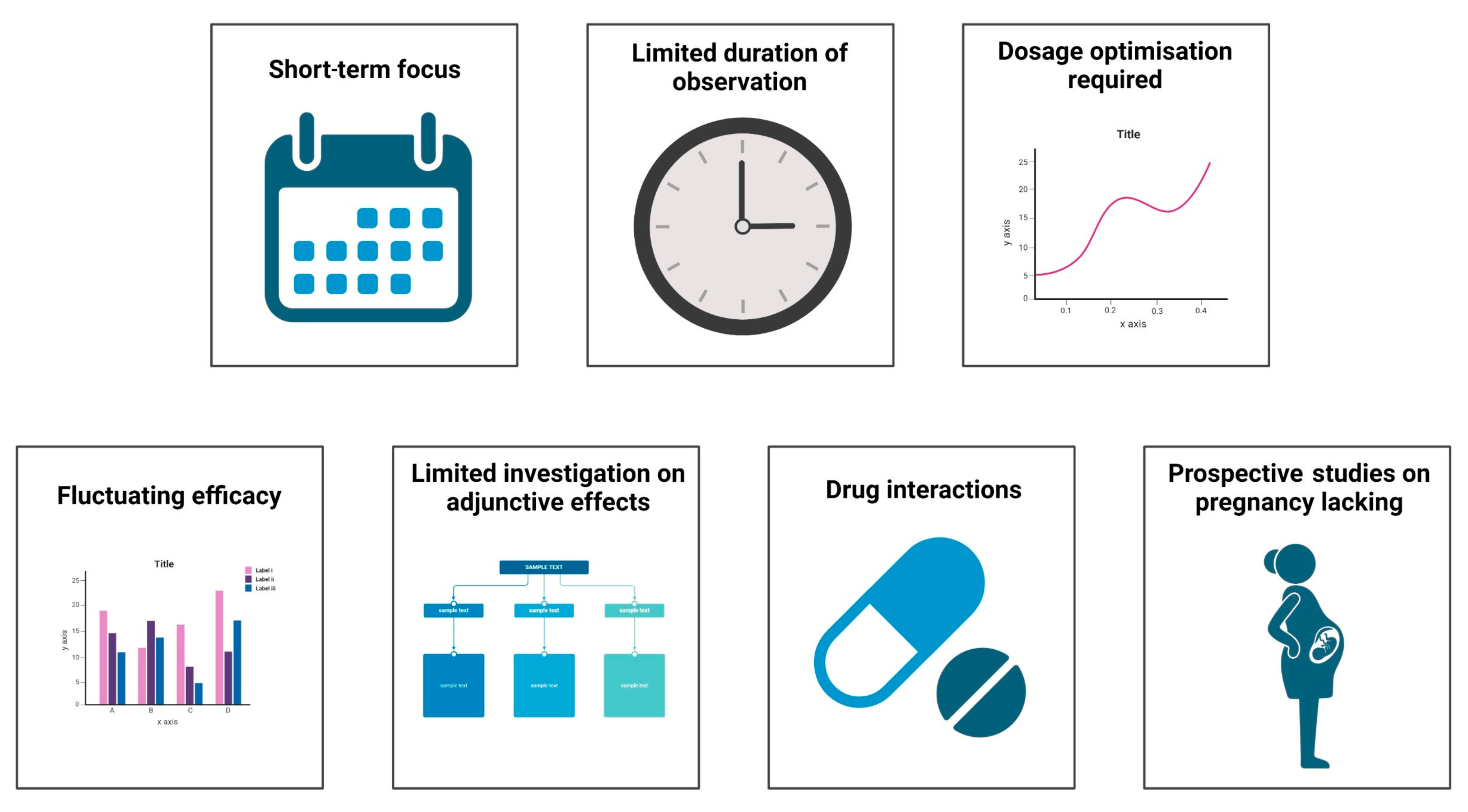

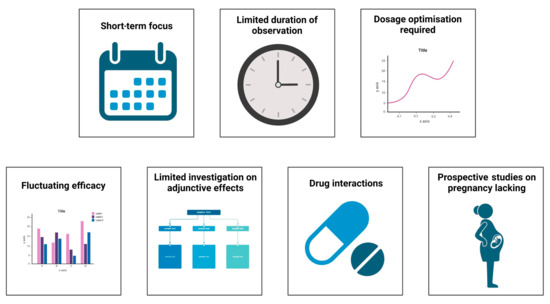

The critical challenges in the current research on metamizole in various clinical conditions are depicted in Figure 3. Currently, most articles on metamizole are randomised control studies, comparative studies, and systematic reviews with a few cross-sectional studies. These studies only identify the short-term effectiveness of the drug in pain management and highlight the acute onset of side effects such as agranulocytosis. Few long-term cohort and prospective studies highlight the drug’s long-term effectiveness and impact on various organs. Most studies only follow the patient for a week at a maximum, which is inadequate for major surgeries. In addition to this, patients were often given some dosage of the drug despite undergoing different surgical procedures. Certain studies assessed pain only at rest, and the patient’s mobility after treatment was not reported. Studies have also unequally distributed the drug amongst participants, which may add as a source of error in calculating the efficacy of the number of side effects produced by the drug.

Figure 3.

Challenges in current research of metamizole.

Despite various comparative studies between the drugs, the drug’s efficacy kept fluctuating. Adverse effects of combinations of drugs have not been extensively studied. Francisco Javier Lopez-Munoz et al. [89] performed a study on improving antinociception while decreasing the impact of constipation by combining metamizole and tramadol in arthritic rats. Furthermore, there have been limited investigations on drug interactions and their impact on efficacy. Prospective studies on the effects of the drug on pregnant mothers, such as those performed by Katarina Dathe et al., are required, because there have been varying impacts on the impact of the drug on the fetus whilst taking the drug during pregnancy [90,91].

9. Conclusions

Metamizole has been critical in managing pain in musculoskeletal disorders, pyrexia, and analgesia for over 90 years. Despite its usage since 1920, the drug’s mechanism of action continues to be elusive, with many theories being put forward, cementing its role in antinociception, analgesic, and antispasmolytic effects. Despite various articles suggesting the effective use of the drug in pain management, fluctuating results between different studies raise questions about the efficacy of the drug. However, the drug has been consistent in reducing the number of narcotic analgesics consumed and increasing the duration between the administration of analgesics and the demand for narcotic analgesics, thus effectively reducing the incidence of side effects from consumption of narcotic analgesics. Furthermore, the drug’s ability to redirect prostaglandin synthesis protects against gastric side effects. Despite having fewer adverse effects when compared to other drugs of similar efficacy, reports on agranulocytosis have become a prime reason for the withdrawal of the drug from various markets. Although many countries are wary of the drug’s efficacy and side effect profile, this review explores a more comprehensive aspect focused on multiple dimensions of drug application and findings found thus far regarding its usage, efficacy, and side effect profile. More conclusive research on the side effects of the drug would shed light on ways to decrease the incidence of the side effects and further increase the drug’s efficacy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: M.J. and F.M.; writing: S.M., N.J., S.R., M.J. and F.M.; images: S.B. and S.R.; supervision and administration: N.M. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Low Back Pain, 1990–2020, Its Attributable Risk Factors, and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malanga, G.A.; Yan, N.; Stark, J. Mechanisms and Efficacy of Heat and Cold Therapies for Musculoskeletal Injury. Postgrad. Med. 2015, 127, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Galán, M.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.-J.; López-Martínez, J. Musculoskeletal Disorders: OWAS Review. Ind. Health 2017, 55, 314–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, B.R.; Vieira, E.R. Risk Factors for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review of Recent Longitudinal Studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawker, G.A. The Assessment of Musculoskeletal Pain. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35 (Suppl. S107), 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Lobo, C.; Becerro-de-Bengoa-Vallejo, R.; Losa-Iglesias, M.E.; Rodríguez-Sanz, D.; López-López, D.; San-Antolín, M. Biomarkers and Nutrients in Musculoskeletal Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, C.; Du, Y.; O’Connell, T.M. Applications of Lipidomics to Age-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2021, 19, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelin, E.; Weinstein, S.; King, T. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 46, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurie, E.; Siebert, S.; Yongolo, N.; Halliday, J.E.B.; Biswaro, S.M.; Krauth, S.J.; Kilonzo, K.G.; Mmbaga, B.T.; McIntosh, E. Evidencing the Clinical and Economic Burden of Musculoskeletal Disorders in Tanzania: Paving the Way for Urgent Rheumatology Service Development. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2023, 8, rkad110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, S.; Bulat, E.; Massawe, H.; Pallangyo, A.; Premkumar, A.; Sheth, N. The Economic Burden of Non-Fatal Musculoskeletal Injuries in Northeastern Tanzania. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, P.-H.; Wu, O.; Geue, C.; McIntosh, E.; McInnes, I.B.; Siebert, S. Economic Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Literature in Biologic Era. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, N.N.; Mugarura, R.; Potter, J.; Stephens, T.; Rehavi, M.M.; Francois, P.; Blachut, P.A.; O’Brien, P.J.; Fashola, B.K.; Mezei, A.; et al. Economic Loss Due to Traumatic Injury in Uganda: The Patient’s Perspective. Injury 2016, 47, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juillard, C.; Labinjo, M.; Kobusingye, O.; Hyder, A.A. Socioeconomic Impact of Road Traffic Injuries in West Africa: Exploratory Data from Nigeria. Inj. Prev. 2010, 16, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mock, C.N.; Gloyd, S.; Adjei, S.; Acheampong, F.; Gish, O. Economic Consequences of Injury and Resulting Family Coping Strategies in Ghana. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2003, 35, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, J.; Moseley, G.L.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Cashin, A.; Davies, M.; Hübscher, M. Exercise for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Musculoskelet. Care 2017, 15, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babatunde, O.O.; Jordan, J.L.; Van der Windt, D.A.; Hill, J.C.; Foster, N.E.; Protheroe, J. Effective Treatment Options for Musculoskeletal Pain in Primary Care: A Systematic Overview of Current Evidence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Acupuncture and Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DE Oliveira, M.F.; Johnson, D.S.; Demchak, T.; Tomazoni, S.S.; Leal-Junior, E.C. Low-Intensity LASER and LED (Photobiomodulation Therapy) for Pain Control of the Most Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 58, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, F.; Bantel, C.; Jobski, K. Agranulocytosis Attributed to Metamizole: An Analysis of Spontaneous Reports in EudraVigilance 1985-2017. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 126, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupu, G.; Bel, L.; Andrei, S. Pain Management and Analgesics Used in Small Mammals during Post-Operative Period with an Emphasis on Metamizole (Dipyrone) as an Alternative Medication. Molecules 2022, 27, 7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, S.; Bartels, D.B.; Lange, R.; Sandford, L.; Gurwitz, J. Safety of Metamizole: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasiecka, A.; Maślanka, T.; Jaroszewski, J.J. Pharmacological Characteristics of Metamizole. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2014, 17, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boblewska, J.; Dybowski, B. Methodology and Findings of Randomized Clinical Trials on Pharmacologic and Non-Pharmacologic Interventions to Treat Renal Colic Pain—A Review. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2023, 76, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnenbelt-Peters, J.; van der Heijden, C.; Ekhart, C.; Bos, J.; Bruhn, J.; Kramers, C. Metamizole (Dipyrone) as an Alternative Agent in Postoperative Analgesia in Patients with Contraindications for Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Pain. Pract. 2017, 17, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sittl, R.; Bäumler, P.; Stumvoll, A.-M.; Irnich, D.; Zwißler, B. Considerations concerning the perioperative use of metamizole. Anaesthesist 2019, 68, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleutério, O.H.P.; Veronezi, R.N.; Martinez-Sobalvarro, J.V.; Ferreira de Oliveira Marrafon, D.A.; Porto Eleutério, L.; Radighieri Rascado, R.; Dos Reis, T.M.; Cardoso Podesta, M.H.M.; Torres, L.H. Safety of Metamizole (Dipyrone) for the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Pain—An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilla, B.; Güney-Deniz, H. Musculoskeletal Treatment in Haemophilia. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearn, L.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Single Dose Dipyrone (Metamizole) for Acute Postoperative Pain in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD011421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomidis Chatzimanouil, M.K.; Goppelt, I.; Zeissig, Y.; Sachs, U.J.; Laass, M.W. Metamizole-Induced Agranulocytosis (MIA): A Mini Review. Mol. Cell. Pediatr. 2023, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova, I.; Tencheva, J.; Voinikov, J.; Petkova, V.; Benbasat, N.; Danchev, N. Metamizole: A Review Profile of a Well-Known “Forgotten” Drug. Part I: Pharmaceutical and Nonclinical Profile. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2012, 26, 3329–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B.; Cheremina, O.; Bachmakov, J.; Renner, B.; Zolk, O.; Fromm, M.F.; Brune, K. Dipyrone Elicits Substantial Inhibition of Peripheral Cyclooxygenases in Humans: New Insights into the Pharmacology of an Old Analgesic. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 2343–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajaczkowska, R.; Kwiatkowski, K.; Pawlik, K.; Piotrowska, A.; Rojewska, E.; Makuch, W.; Wordliczek, J.; Mika, J. Metamizole Relieves Pain by Influencing Cytokine Levels in Dorsal Root Ganglia in a Rat Model of Neuropathic Pain. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, S.C.; Schmidt, R.; Brenneis, C.; Michaelis, M.; Geisslinger, G.; Scholich, K. Inhibition of Cyclooxygenases by Dipyrone. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, C.; de Gregorio, R.; García-Nieto, R.; Gago, F.; Ortiz, P.; Alemany, S. Regulation of Cyclooxygenase Activity by Metamizol. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 378, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves Dos Santos, G.; Vieira, W.F.; Vendramini, P.H.; Bassani da Silva, B.; Fernandes Magalhães, S.; Tambeli, C.H.; Parada, C.A. Dipyrone Is Locally Hydrolyzed to 4-Methylaminoantipyrine and Its Antihyperalgesic Effect Depends on CB2 and Kappa-Opioid Receptors Activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 874, 173005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembinska-Kieĉ, A.; Zmuda, A.; Krupinska, J. Inhibition of Prostaglandin Synthetase by Aspirin-like Drugs in Different Microsomal Preparations. Adv. Prostaglandin Thromboxane Res. 1976, 1, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Eldor, A.; Polliack, G.; Vlodavsky, I.; Levy, M. Effects of Dipyrone on Prostaglandin Production by Human Platelets and Cultured Bovine Aortic Endothelial Cells. Thromb. Haemost. 1983, 49, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weithmann, K.U.; Alpermann, H.G. Biochemical and Pharmacological Effects of Dipyrone and Its Metabolites in Model Systems Related to Arachidonic Acid Cascade. Arzneimittelforschung 1985, 35, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eldor, A.; Zylber-Katz, E.; Levy, M. The Effect of Oral Administration of Dipyrone on the Capacity of Blood Platelets to Synthesize Thromboxane A2 in Man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1984, 26, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frölich, J.C.; Rupp, W.A.; Zapf, R.M.; Badian, M.J. The Effects of Metamizol on Prostaglandin Synthesis in Man. Agents Actions Suppl. 1986, 19, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.I.F.; Cunha, F.Q.; Cunha, T.M. Peripheral Nitric Oxide Signaling Directly Blocks Inflammatory Pain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 176, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulmez, S.E.; Gurdal, H.; Tulunay, F.C. Airway Smooth Muscle Relaxations Induced by Dipyrone. Pharmacology 2006, 78, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aster, H.-C.; Evdokimov, D.; Braun, A.; Üçeyler, N.; Sommer, C. Analgesic Medication in Fibromyalgia Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain. Res. Manag. 2022, 2022, 1217717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes de Brito, C.A.; von Sohsten, A.K.A.; de Sa Leitao, C.C.; de Cassia Coelho Moraes de Brito, R.; De Azevedo Valadares, L.D.; Araujo Magnata da Fonte, C.; Barbosa de Mesquita, Z.; Cunha, R.V.; Vinhal Frutuoso, L.C.; Carneiro Leao, H.M. Pharmacologic Management of Pain in Patients with Chikungunya: A Guideline. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016, 49, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderer, G.; Hellmeyer, L.; Hadji, P. Clinical Management of a Pregnant Patient with Type I Osteogenesis Imperfecta Using Quantitative Ultrasonometry—A Case Report. Ultraschall Med. 2008, 29, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reist, L.; Erlenwein, J.; Meissner, W.; Stammschulte, T.; Stüber, F.; Stamer, U.M. Dipyrone Is the Preferred Nonopioid Analgesic for the Treatment of Acute and Chronic Pain. A Survey of Clinical Practice in German-Speaking Countries. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Alba, J.E.; Serna-Echeverri, L.S.; Valladales-Restrepo, L.F.; Machado-Duque, M.E.; Gaviria-Mendoza, A. Use of Tramadol or Other Analgesics in Patients Treated in the Emergency Department as a Risk Factor for Opioid Use. Pain. Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 8847777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiró, A.M.; Martínez, J.; Martínez, E.; de Madaria, E.; Llorens, P.; Horga, J.F.; Pérez-Mateo, M. Efficacy and Tolerance of Metamizole versus Morphine for Acute Pancreatitis Pain. Pancreatology 2008, 8, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babej-Dölle, R.; Freytag, S.; Eckmeyer, J.; Zerle, G.; Schinzel, S.; Schmeider, G.; Stankov, G. Parenteral Dipyrone versus Diclofenac and Placebo in Patients with Acute Lumbago or Sciatic Pain: Randomized Observer-Blind Multicenter Study. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994, 32, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muriel-Villoria, C.; Zungri-Telo, E.; Díaz-Curiel, M.; Fernández-Guerrero, M.; Moreno, J.; Puerta, J.; Ortiz, P. Comparison of the Onset and Duration of the Analgesic Effect of Dipyrone, 1 or 2 g, by the Intramuscular or Intravenous Route, in Acute Renal Colic. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995, 48, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlik, I.; Suchy, J.; Pacík, D.; Bokr, R.; Sust, M.; Villoria, J.; Abadías, M. Evaluation of Cizolirtine Citrate to Treat Renal Colic Pain Study Group Comparison of Cizolirtine Citrate and Metamizol Sodium in the Treatment of Adult Acute Renal Colic: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Clinical Pilot Study. Clin. Ther. 2004, 26, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Carpena, J.; Domínguez-Hervella, F.; García, I.; Gene, E.; Bugarín, R.; Martín, A.; Tomás-Vecina, S.; García, D.; Serrano, J.A.; Roman, A.; et al. Comparison of Intravenous Dexketoprofen and Dipyrone in Acute Renal Colic. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 63, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz Dilmen, O.; Tunali, Y.; Cakmakkaya, O.S.; Yentur, E.; Tutuncu, A.C.; Tureci, E.; Bahar, M. Efficacy of Intravenous Paracetamol, Metamizol and Lornoxicam on Postoperative Pain and Morphine Consumption after Lumbar Disc Surgery. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2010, 27, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.D. A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study of Dipyrone and Aspirin in Post-Operative Orthopaedic Patients. J. Int. Med. Res. 1986, 14, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, N.; Allvin, R.; Amilon, A.; Ohlsson, T.; Hallén, J. Postoperative Analgesia at Home after Ambulatory Hand Surgery: A Controlled Comparison of Tramadol, Metamizol, and Paracetamol. Anesth. Analg. 2001, 92, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oreskovic, Z.; Bicanic, G.; Hrabac, P.; Tripkovic, B.; Delimar, D. Treatment of Postoperative Pain after Total Hip Arthroplasty: Comparison between Metamizol and Paracetamol as Adjunctive to Opioid Analgesics-Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomised Study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2014, 134, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodner, G.; Gogarten, W.; Van Aken, H.; Hahnenkamp, K.; Wempe, C.; Freise, H.; Cosanne, I.; Huppertz-Thyssen, M.; Ellger, B. Efficacy of Intravenous Paracetamol Compared to Dipyrone and Parecoxib for Postoperative Pain Management after Minor-to-Intermediate Surgery: A Randomised, Double-Blind Trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 28, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stessel, B.; Boon, M.; Pelckmans, C.; Joosten, E.A.; Ory, J.-P.; Wyckmans, W.; Evers, S.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Van de Velde, M.; Buhre, W.F.F.A. Metamizole vs. Ibuprofen at Home after Day Case Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomised Controlled Noninferiority Trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izhar, T. Novalgin in Pain and Fever. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 1999, 49, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, M.; Barutell, C.; Rull, M.; Gálvez, R.; Pallarés, J.; Vidal, F.; Aliaga, L.; Moreno, J.; Puerta, J.; Ortiz, P. Efficacy and Tolerance of Oral Dipyrone versus Oral Morphine for Cancer Pain. Eur. J. Cancer 1994, 30, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleine-Borgmann, J.; Wilhelmi, J.; Kratel, J.; Baumann, F.; Schmidt, K.; Zunhammer, M.; Bingel, U. Tilidine and Dipyrone (Metamizole) in Cold Pressor Pain: A Pooled Analysis of Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety in Healthy Volunteers. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, L.E.; Lezcano, W.; Alvarez, H.D.; Joaqui, W. Analgesic Effectiveness of Dipyrone (Metamizol) for Postoperative Pain after Herniorrhaphy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Dose-Response Study. Pain. Pract. 2012, 12, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas, M.E.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Bagán, J.V.; Santamaría, J.; Peñarrocha, M.; Donado, M.; Puerta, J.L.; García-Magaz, I.; Ruíz, J.; Ortiz, P. Oral Metamizol (1 g and 2 g) versus Ibuprofen and Placebo in the Treatment of Lower Third Molar Surgery Pain: Randomised Double-Blind Multi-Centre Study. Cooperative Study Group. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 53, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favarini, V.T.; Lima, C.A.A.; da Silva, R.A.; Sato, F.R.L. Is Dipyrone Effective as a Preemptive Analgesic in Third Molar Surgery? A Pilot Study. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohdewald, P.; Granitzki, H.W.; Neddermann, E. Comparison of the Analgesic Efficacy of Metamizole and Tramadol in Experimental Pain. Pharmacology 1988, 37, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaertner, J.; Stamer, U.M.; Remi, C.; Voltz, R.; Bausewein, C.; Sabatowski, R.; Wirz, S.; Müller-Mundt, G.; Simon, S.T.; Pralong, A.; et al. Metamizole/Dipyrone for the Relief of Cancer Pain: A Systematic Review and Evidence-Based Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Benesic, A.; Gerbes, A.L. Further Evidence for the Hepatotoxic Potential of Metamizole. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 1587–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebode, M.; Reike-Kunze, M.; Weidemann, S.; Zenouzi, R.; Hartl, J.; Peiseler, M.; Liwinski, T.; Schulz, L.; Weiler-Normann, C.; Sterneck, M.; et al. Metamizole: An Underrated Agent Causing Severe Idiosyncratic Drug-induced Liver Injury. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova, I.; Marinov, L.; Georgieva, A.; Toshkova, R.; Malchev, M.; Voynikov, Y.; Kostadinova, I. Metamizole (Dipyrone)—Cytotoxic and Antiproliferative Effects on HeLa, HT-29 and MCF-7 Cancer Cell Lines. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018, 32, 1327–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguley, C.M. Agranulocytosis induced by Dipyrone, a hazardous antipyretic and analgesic. JAMA 1964, 189, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedhai, Y.R.; Lamichhane, A.; Gupta, V. Agranulocytosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, K.W.; West, D.P. Immunology of Adverse Drug Reactions. Pharmacotherapy 1982, 2, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrès, E.; Zimmer, J.; Mecili, M.; Weitten, T.; Alt, M.; Maloisel, F. Clinical Presentation and Management of Drug-Induced Agranulocytosis. Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2011, 4, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, Y.; Toh Yoon, E.W. Severe Drug-Induced Agranulocytosis Successfully Treated with Recombinant Human Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor. Case Rep. Med. 2018, 2018, 8439791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenmalm, K.; Spigset, O. Agranulocytosis and Other Blood Dyscrasias Associated with Dipyrone (Metamizole). Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 58, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zukowski, M.; Kotfis, K. Safety of metamizole and paracetamol for acute pain treatment. Anestezjol. Intens. Ter. 2009, 41, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, E.L.; Song, Y. Adverse Effects of Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors on Renal and Arrhythmia Events: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. JAMA 2006, 296, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harirforoosh, S.; Asghar, W.; Jamali, F. Adverse Effects of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs: An Update of Gastrointestinal, Cardiovascular and Renal Complications. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 16, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Süleyman, H.; Demircan, B.; Karagöz, Y. Anti-Inflammatory and Side Effects of Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors. Pharmacol. Rep. 2007, 59, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.C.; Reid, C.M.; Aw, T.J.; Liew, D.; Haas, S.J.; Krum, H. Do COX-2 inhibitors raise blood pressure more than nonselective NSAIDs and placebo? An updated meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporali, R.; Montecucco, C. Cardiovascular Effects of Coxibs. Lupus 2005, 14, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, S.J.; Rowett, D.S.; Sayer, G.P.; Whicker, S.D.; Saltman, D.C.; Mant, A. All-Cause Mortality of Elderly Australian Veterans Using COX-2 Selective or Non-Selective NSAIDs: A Longitudinal Study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 71, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guvenc, Y.; Billur, D.; Aydin, S.; Ozeren, E.; Demirci, A.; Alagoz, F.; Dalgic, A.; Belen, D. Metamizole Sodium Induce Neural Tube Defects in a Chick Embryo Model. Turk. Neurosurg. 2016, 26, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brandlistuen, R.E.; Ystrom, E.; Nulman, I.; Koren, G.; Nordeng, H. Prenatal Paracetamol Exposure and Child Neurodevelopment: A Sibling-Controlled Cohort Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, J.C.; Morrison, E.E.; MacIntyre, I.M.; Dear, J.W.; Webb, D.J. Long-term Adverse Effects of Paracetamol—A Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2218–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Z.; Ritz, B.; Rebordosa, C.; Lee, P.-C.; Olsen, J. Acetaminophen Use during Pregnancy, Behavioral Problems, and Hyperkinetic Disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kötter, T.; da Costa, B.R.; Fässler, M.; Blozik, E.; Linde, K.; Jüni, P.; Reichenbach, S.; Scherer, M. Metamizole-Associated Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sener, M.; Yilmazer, C.; Yilmaz, I.; Bozdogan, N.; Ozer, C.; Donmez, A.; Arslan, G. Efficacy of Lornoxicam for Acute Postoperative Pain Relief after Septoplasty: A Comparison with Diclofenac, Ketoprofen, and Dipyrone. J. Clin. Anesth. 2008, 20, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Muñoz, F.J.; Moreno-Rocha, L.A.; Bravo, G.; Guevara-López, U.; Domínguez-Ramírez, A.M.; Déciga-Campos, M. Enhancement of Antinociception but Not Constipation by Combinations Containing Tramadol and Metamizole in Arthritic Rats. Arch. Med. Res. 2013, 44, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dathe, K.; Frank, J.; Padberg, S.; Hultzsch, S.; Beck, E.; Schaefer, C. Fetal Adverse Effects Following NSAID or Metamizole Exposure in the 2nd and 3rd Trimester: An Evaluation of the German Embryotox Cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dathe, K.; Padberg, S.; Hultzsch, S.; Meixner, K.; Tissen-Diabaté, T.; Meister, R.; Beck, E.; Schaefer, C. Metamizole Use during First Trimester—A Prospective Observational Cohort Study on Pregnancy Outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2017, 26, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).