Periodontal Patients’ Perceptions and Knowledge of Dental Implants—A Questionnaire Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Methodology and Questionnaire

- patients’ attitudes to missing teeth and sources of knowledge about dental implants;

- patients’ knowledge about dental implants and understanding of the implantation process;

- knowledge about peri-implantitis and other treatment implications;

- factors encouraging and discouraging patients to undergo implantation.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Group Studied

3.2. Patients’ Attitudes to Missing Teeth and Sources of Knowledge about Dental Implants

- Summary:

- Details:

3.3. Patients’ Knowledge about Dental Implants

- Summary:

- Details:

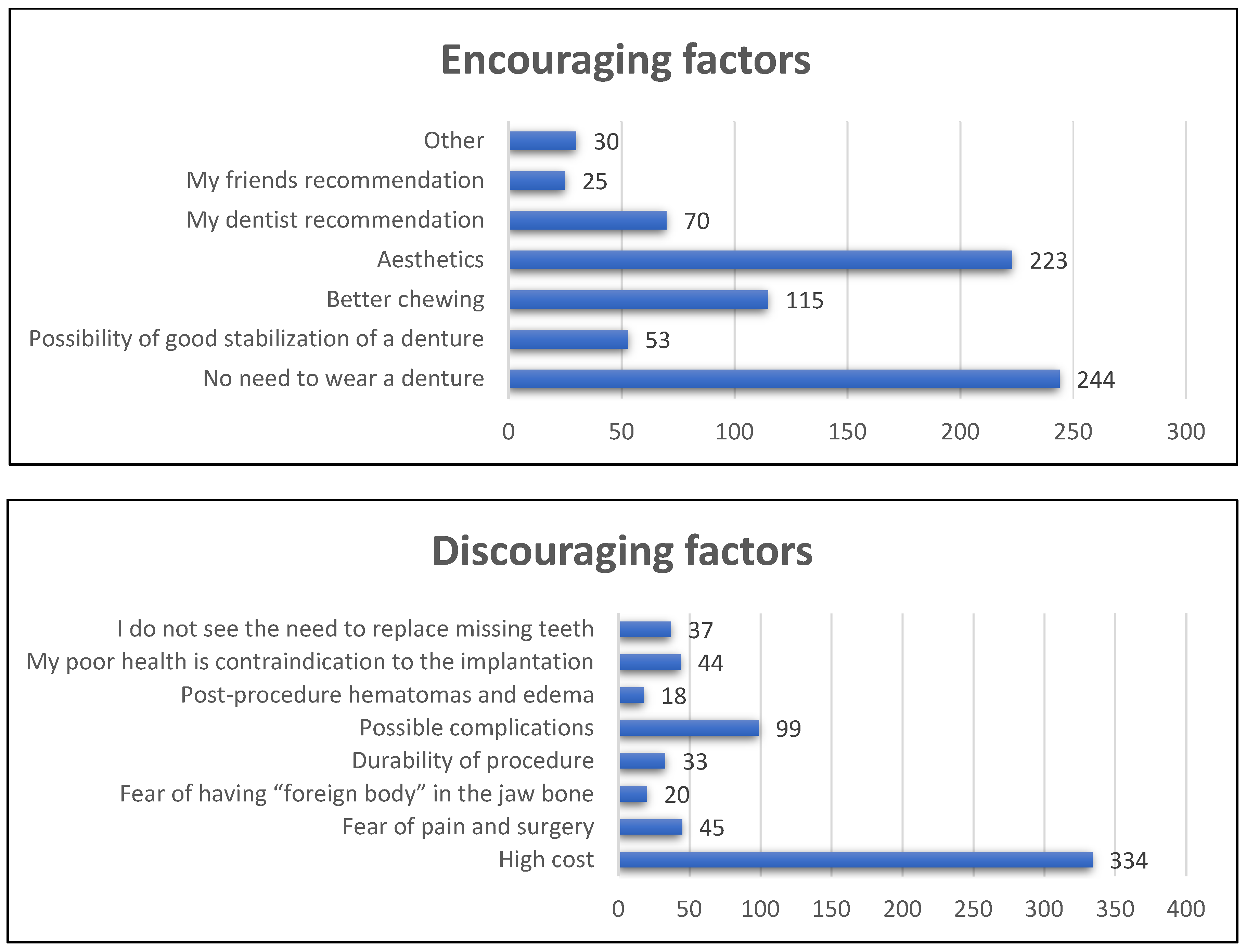

3.4. Encouraging and Discouraging Factors to Implantation

- Summary

- Details

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albandar, J.M. Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 49, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, D. Review finds that severe periodontitis affects 11% of the world population. Evid. Based Dent. 2014, 15, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Lamster, I.B.; Levin, L. Current concepts in the management of periodontitis. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.S.; Dos Santos, J.N.; Ramalho, L.M.; Chaves, S.; Figueiredo, A.L.; Cury, P.R. Risk indicators for tooth loss in Kiriri Adult Indians: A cross-sectional study. Int. Dent. J. 2015, 65, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broers, D.L.M.; Dubois, L.; de Lange, J.; Su, N.; de Jongh, A. Reasons for tooth removal in adults: A systematic review. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, P.; Kohlmann, T.; Nauck, M.; Biffar, R.; Kocher, T. Effect of body shape and inflammation on tooth loss in men and women. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Levin, L. In the dental implant era, why do we still bother saving teeth? Dent. Traumatol. 2019, 35, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelig, R.; Goldstein, S.; Touger-Decker, R.; Firestone, E.; Golden, A.; Johnson, Z.; Kaseta, A.; Sackey, J.; Tomesko, J.; Parrott, J.S. Tooth loss and nutritional status in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2022, 7, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabé, E.; de Oliveira, C.; de Oliveira Duarte, Y.A.; Bof de Andrade, F.; Sabbah, W. Social participation and tooth loss, vision, and hearing impairments among older Brazilian adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 3152–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudsi, Z.; Fenlon, M.R.; Johal, A.; Baysan, A. Assessment of psychological disturbance in patients with tooth loss: A systematic review of assessment tools. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elani, H.W.; Starr, J.R.; Da Silva, J.D.; Gallucci, G.O. Trends in dental implant use in the U.S., 1999–2016, and projections to 2026. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angkaew, C.; Serichetaphongse, P.; Krisdapong, S.; Dart, M.M.; Pimkhaokham, A. Oral health-related quality of life and esthetic outcome in single anterior maxillary implants. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2017, 28, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Meda, R.; Esquivel, J.; Blatz, M.B. The esthetic biological contour concept for implant restoration emergence profile design. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, C.A.; Ferro-Alves, M.L.; Okamoto, R.; Mendonça, M.R.; Pellizzer, E.P. Short dental implants versus standard dental implants placed in the posterior jaws: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 2016, 47, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, J.A.; Senna, P.M.; Francischone, C.E.; Francischone Junior, C.E.; Sotto-Maior, B.S. Influence of the diameter of dental implants replacing single molars: 3- to 6-year follow-up. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, C.; Carpentieri, J. Treatment of maxillary jaws with dental implants: Guidelines for treatment. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, D.; ten Bruggenkate, C.M. Treatment of fully edentulous patients with ITI implants. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2000, 11 (Suppl. S1), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siadat, H.; Alikhasi, M.; Beyabanaki, E. Interim prosthesis options for dental implants. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirynen, M.; Herrera, D.; Teughels, W.; Sanz, M. Implant therapy: 40 years of experience. Periodontology 2000 2014, 66, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belser, U.C.; Buser, D.; Hess, D.; Schmid, B.; Bernard, J.P.; Lang, N.P. Aesthetic implant restorations in partially edentulous patients–a critical appraisal. Periodontology 2000 1998, 17, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Working Group 3 of the VIII European Workshop on Periodontology. Clinical research in implant dentistry: Evaluation of implant-supported restorations, aesthetic and patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39 (Suppl. S12), 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jivraj, S.; Chee, W. Rationale for dental implants. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 200, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Levin, L. Barriers related to dental implant treatment acceptance by patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2022, 37, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, C.M.; Zimmer, W.M.; Williams, J.; Liesener, J. Public awareness and acceptance of dental implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1992, 7, 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, T.I. Public awareness, information sources and evaluation of oral implant treatment in Norway. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2000, 11, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, F.; Salem, K.; Barbezat, C.; Herrmann, F.R.; Schimmel, M. Knowledge and attitude of elderly persons towards dental implants. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e914–e923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupińska, A.M.; Bogucki, Z. Evaluation of patients’ awareness and knowledge regarding dental implants among patients of the Department of Prosthetic Dentistry at Wroclaw Medical University in Poland. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 32, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeb, G.; Wheeler, B.; Jones, M.; Carrico, C.; Laskin, D.; Deeb, J.G. Public and patient knowledge about dental implants. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj Husain, A.; De Cicco, O.; Stadlinger, B.; Bosshard, F.A.; Schmidt, V.; Özcan, M.; Valdec, S. A survey on attitude, awareness, and knowledge of patients regarding the use of dental implants at a Swiss University Clinic. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaldi, M.S.; Alshuaibi, A.A.; Alshahran, S.S.; Koppolu, P.; Abdelrahim, R.K.; Swapna, L.A. Perception, knowledge, and attitude of individuals from different regions of Saudi Arabia toward dental implants and bone grafts. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. S1), S575–S579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dwairi, Z.N.; El Masoud, B.M.; Al-Afifi, S.A.; Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Lynch, E. Awareness, attitude, and expectations toward dental implants among removable prostheses wearers. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 23, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.; Bahammam, S.; Chen, C.Y.; Hojo, Y.; Kim, D.; Hisatomo, K.; Da Silva, J.; Nagai, S. A cross-sectional survey of patient’s perception and knowledge of dental implants in Japan. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, G.; Haas, R.; Mailath, G.; Teller, C.; Zechner, W.; Watzak, G.; Watzek, G. Representative marketing-oriented study on implants in the Austrian population. I. Level of information, sources of information and need for patient information. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2003, 14, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolińska, E.; Milewski, R.; Pietruska, M.J.; Gumińska, K.; Prysak, N.; Tarasewicz, T.; Janica, M.; Pietruska, M. Periodontitis-related knowledge and its relationship with oral health behavior among adult patients seeking professional periodontal care. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, I.; Krüger, K.; Jockusch, J. Age-related knowledge deficit and attitudes towards oral implants: Survey-based examination of the correlation between patient age and implant therapy awareness. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Tomasi, C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42 (Suppl. S16), S158–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, G.; Haas, R.; Mailath, G.; Teller, C.; Bernhart, T.; Monov, G.; Watzek, G. Representative marketing-oriented study on implants in the Austrian population. II. Implant acceptance, patient-perceived cost and patient satisfaction. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2003, 14, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekpınar, L.; Yiğit, V. Cost-effectiveness analysis of implant-supported single crown and tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses in Türkiye. Value Health Reg. Issues 2024, 42, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Karoussis, I.; Bürgin, W.; Brägger, U.; Lang, N.P. Patients’ satisfaction following implant therapy. A 10-year prospective cohort study. Clin. Oral. Implants Res. 2005, 16, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bäumer, D.; Ozga, A.K.; Körner, G.; Bäumer, A. Patient satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life 10 years after implant placement. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradyachaipimol, N.; Tangsathian, T.; Supanimitkul, K.; Sophon, N.; Suwanwichit, T.; Manopattanasoontorn, S.; Arunyanak, S.P.; Kungsadalpipob, K. Patient satisfaction following dental implant treatment: A survey. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, H.Y.; Roccuzzo, A.; Stähli, A.; Salvi, G.E.; Lang, N.P.; Sculean, A. Oral health-related quality of life of patients rehabilitated with fixed and removable implant-supported dental prostheses. Periodontology 2000 2022, 88, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| total | 467 | 100 | |

| age | 18–30 | 171 | 9.2 |

| 31–50 | 194 | 36.6 | |

| 51–70 | 196 | 41.5 | |

| 71 and above | 56 | 12 | |

| not stated | 3 | 0.6 | |

| gender | female | 318 | 68.1 |

| male | 142 | 30.4 | |

| not stated | 7 | 1.5 | |

| education | primary | 11 | 2.4 |

| secondary | 184 | 39.4 | |

| incomplete higher | 50 | 10.7 | |

| higher | 214 | 45.8 | |

| other | 2 | 0.4 | |

| not stated | 6 | 1.3 | |

| place of residence | village | 89 | 19.1 |

| small city | 105 | 22.5 | |

| city above 50,000 | 225 | 54.6 | |

| not stated | 18 | 3.8 | |

| missing teeth | yes | 337 | 72.2 |

| no | 126 | 27 | |

| not stated | 4 | 0.8 |

| Question | Possible Answers | Number of Answers | Percentage of Answers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think that replacing missing teeth is important? | Yes | 447 | 95.7% |

| No | 3 | 0.6% | |

| I don’t know | 17 | 3.6% | |

| Have you heard about dental implants? | Yes, a lot | 151 | 32.4% |

| Yes, a little | 283 | 60.7% | |

| No | 32 | 6.7% | |

| If yes, how did you learn about implants? | Dentist | 145 | 32.9% |

| Family and friends | 166 | 37.6% | |

| Newspapers and magazines | 82 | 18.6% | |

| Radio and television | 87 | 19.7% | |

| Internet | 188 | 42.6% | |

| Other | 21 | 4.8% | |

| Where are the implants placed? | In the jaw bone | 343 | 79.6% |

| In the gum | 64 | 14.8% | |

| In the adjacent teeth | 30 | 7% | |

| What material are implants made of? | Porcelain | 125 | 27.5% |

| Stainless steel | 34 | 7.5% | |

| Titanium | 121 | 26.6% | |

| Ceramics | 48 | 10.6% | |

| I don’t know | 197 | 43.4% | |

| Is the implant procedure suitable for every patient? | Yes | 88 | 19.17% |

| No | 157 | 34.2% | |

| I don’t know | 214 | 46.6% | |

| Did you know that implantation may end in a failure? | Yes | 229 | 50.8% |

| No | 222 | 49.2% | |

| Do you think that periodontitis is a contraindication to implantation? | Yes | 168 | 36.8% |

| No | 42 | 9.2% | |

| I don’t know | 246 | 53.9% | |

| Did you know that often, before implantation, bone reconstruction is needed? | Yes | 203 | 45.5% |

| No | 243 | 54.5% | |

| Did you know that implants should be cared for like teeth? | Yes | 423 | 92.7% |

| No | 32 | 7% | |

| Did you hear about peri-implantitis? | Yes | 127 | 28% |

| No | 327 | 72% | |

| Do you want to know more about implants? | Yes | 284 | 62.8% |

| No | 168 | 37.2% | |

| Did you hear direct opinion from someone who has a dental implant? | Yes | 160 | 35% |

| No | 296 | 65% | |

| If yes, who was it? | Someone from my family | 63 | 35.8% |

| A friend | 101 | 57% | |

| Someone from TV | 13 | 7.4% | |

| Someone from the internet | 21 | 12% | |

| Was the opinion positive? | Yes | 158 | 90.3% |

| No | 17 | 9.7% | |

| Are you satisfied with your prosthetic restorations? | Yes, very satisfied | 69 | 24.4% |

| Yes, they are acceptable | 142 | 50.2% | |

| No | 72 | 25.4% | |

| What would encourage you to have an implant? | No need to wear a denture | 244 | 54.1% |

| Possibility of good stabilization of a denture | 53 | 11.8% | |

| Better chewing | 115 | 25.5% | |

| Aesthetics | 223 | 49.4% | |

| My dentist’s recommendation | 70 | 15.5% | |

| My friends’ recommendation | 25 | 5.5% | |

| Other | 30 | 6.7% | |

| What discourages you from having an implant? | High cost | 334 | 76.3% |

| Fear of pain and surgery | 45 | 10.3% | |

| Fear of having a “foreign body” in the jaw bone | 20 | 4.6% | |

| Durability of procedure | 33 | 7.6% | |

| Possible complications | 99 | 22.7% | |

| Post-procedure hematomas and edema | 18 | 4.1% | |

| My poor health is a contraindication to implantation | 44 | 10.1% | |

| I do not see the need to replace missing teeth | 37 | 8.5% | |

| Do you think that you will decide to have dental implants in the future? | Yes | 119 | 26.2% |

| No | 67 | 14.8% | |

| I don’t know | 268 | 59% |

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Implants are embedded in the bone | 18–30 (n = 36) | 31–50 (n = 127) | 51–70 (n = 146) | ≥71 (n = 32) | 7.9 | p = 0.05 |

| 84% | 79% | 83% | 65% | |||

| Male (n = 100) | Female (n = 237) | 0.1 | NS | |||

| 79% | 80% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 13 | p = 0.01 | |

| n = 6 | n = 122 | n = 35 | n = 174 | |||

| 67% | 73% | 74% | 87% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | 0.7 | NS | ||

| n = 61 | n = 79 | n = 190 | ||||

| 76% | 81% | 80% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 244) | Full teeth (n = 97) | 0.003 | NS | |||

| 80% | 80% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Implants are made of titanium | 18–30 (n = 22) | 31–50 (n = 33) | 51–70 (n = 59) | ≥71 (n = 7) | 24.4 | p = 0.00002 |

| 51% | 20% | 32% | 13% | |||

| Male (n = 26) | Female (n = 92) | 5 | p = 0.02 | |||

| 19% | 30% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 15.7 | p = 0.003 | |

| n = 1 | n = 33 | n = 20 | n = 66 | |||

| 10% | 19% | 41% | 32% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | ||||

| n = 21 | n = 33 | n = 61 | 2 | NS | ||

| 24% | 32% | 24.5% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 21) | Full teeth (n = 8) | 0.01 | NS | |||

| 7% | 7% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Implants are not for every patient | 18–30 (n = 20) | 31–50 (n = 53) | 51–70 (n = 67) | ≥71 (n = 16) | 8 | NS |

| 48% | 32% | 35% | 29% | |||

| Male (n = 41) | Female (n = 115) | 8 | p = 0.02 | |||

| 29% | 37% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 2 | NS | |

| n = 3 | n = 65 | n = 16 | n = 69 | |||

| 30% | 35% | 32% | 33% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | 7 | NS | ||

| n = 24 | n = 29 | n = 96 | ||||

| 28% | 28% | 38% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 110) | Full teeth (n = 46) | 2 | NS | |||

| 33% | 37% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Implantation may end in failure | 18–30 (n = 22) | 31–50 (n = 78) | 51–70 (n = 103) | ≥71 (n = 25) | 2.7 | NS |

| 52% | 47% | 55% | 47% | |||

| Male (n = 67) | Female (n = 160) | 0.4 | NS | |||

| 49% | 52% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 9 | NS | |

| n = 2 | n = 80 | n = 28 | n = 113 | |||

| 22% | 45% | 56% | 55% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | 4 | NS | ||

| n = 35 | n = 51 | n = 134 | ||||

| 41% | 50.5% | 54% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 168) | Full teeth (n = 60) | 0.2 | NS | |||

| 52% | 49% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Periodontitis may implicate implant treatment | 18–30 (n = 30) | 31–50 (n = 62) | 51–70 (n = 65) | ≥71 (n = 10) | 34 | p = 0.00001 |

| 71% | 37% | 35% | 18.5% | |||

| Male (n = 45) | Female (n = 120) | 1.8 | NS | |||

| 32% | 38.5% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 11 | NS | |

| n = 3 | n = 62 | n = 23 | n = 79 | |||

| 30% | 34% | 46% | 38% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | ||||

| n = 27 | n = 39 | n = 99 | 2 | NS | ||

| 31% | 38% | 40% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 108) | Full teeth (n = 60) | 10 | p = 0.006 | |||

| 33% | 48% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Implants may need bone augmen- tation | 18–30 (n = 18) | 31–50 (n = 77) | 51–70 (n = 90) | ≥71 (n = 17) | 4 | NS |

| 43% | 46% | 49.5% | 33% | |||

| Male (n = 50) | Female (n = 150) | 5.6 | NS | |||

| 37% | 49% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 12 | p = 0.01 | |

| n = 1 | n = 67 | n = 24 | n = 107 | |||

| 10% | 39% | 50% | 52% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | ||||

| n = 34 | n = 50 | n = 115 | 2 | NS | ||

| 40% | 49% | 47% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 153) | Full teeth (n = 49) | 3 | NS | |||

| 48% | 39% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Implants needs hygiene like teeth | 18–30 (n = 40) | 31–50 (n = 157) | 51–70 (n = 178) | ≥71 (n = 45) | 9 | p = 0.03 |

| 95% | 93% | 95% | 83% | |||

| Male (n = 120) | Female (n = 297) | 10.5 | p = 0.001 | |||

| 87% | 95.5% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 15 | p = 0.005 | |

| n = 6 | n = 162 | n = 48 | n = 199 | |||

| 66% | 90% | 96% | 96% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | 4 | NS | ||

| n = 77 | n = 98 | n = 234 | ||||

| 89% | 96% | 94% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 303) | Full teeth (n = 116) | 0.5 | NS | |||

| 93% | 94% | |||||

| Age group | Chi-squared | p | ||||

| Did you hear about peri-implantitis? | 18–30 (n = 17) | 31–50 (n = 42) | 51–70 (n = 57) | ≥71 (n = 10) | 7 | NS |

| 40.5% | 25% | 70% | 18% | |||

| Male (n = 30) | Female (n = 96) | 4 | p = 0.04 | |||

| 22% | 31% | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| primary | secondary | incomplete higher | higher | 13 | p = 002 | |

| n = 0 | n = 42 | n = 15 | n = 65 | |||

| 0% | 23% | 31% | 31% | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| village | small city | city above 50,000 | 4 | NS | ||

| n = 27 | n = 34 | n = 60 | ||||

| 31% | 34% | 24% | ||||

| Missing teeth (n = 91) | Full teeth (n = 35) | 0.04 | NS | |||

| 27% | 29% | |||||

| Total | Age | Gender | Education | Missing Teeth | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–30 | 31–50 | 51–70 | 71 and Above | p | Female | Male | p | Primary | Secondary | Incomplete Higher | Higher | p | Yes | No | p | ||

| n | 467 | 171 9.2% | 194 36.6% | 196 41.5% | 56 12% | 318 68.1% | 142 30.4% | 11 2.4% | 184 39.4% | 50 10.7% | 214 45.8% | 337 72.2% | 126 27% | ||||

| Encouraging factors | |||||||||||||||||

| No need to wear prosthesis | 18 42% | 105 62% | 98 54% | 22 42% | p = 0.02 | 180 58% | 60 44% | p = 0.005 | 2 22% | 85 48% | 30 60% | 124 60% | p = 0.02 | 167 52% | 75 60% | NS | |

| Excellent stabilization of prosthesis | 1 2% | 16 9% | 29 16% | 7 13% | NS | 35 12% | 17 12% | NS | 1 11% | 23 13% | 3 6% | 24 12% | NS | 45 14% | 8 6% | p = 0.02 | |

| Better chewing | 14 32% | 31 18% | 53 29% | 16 31% | NS | 80 26% | 34 25% | NS | 1 11% | 51 29% | 7 14% | 54 26% | NS | 80 25% | 34 27% | NS | |

| Aesthetic appearance | 27 63% | 86 51% | 84 46% | 24 46% | NS | 163 53% | 57 42% | p = 0.03 | 5 56% | 76 43% | 22 44% | 114 55% | NS | 155 45% | 67 54% | NS | |

| Dentist’s recommendation | 3 7% | 28 17% | 33 18% | 5 10% | NS | 40 13% | 29 21% | p = 0.02 | 1 11% | 19 11% | 3 6% | 47 23% | p = 0.005 | 50 15% | 20 16% | NS | |

| Friends’ recommendation | 2 5% | 6 4% | 12 7% | 5 10% | NS | 11 4% | 14 10% | p = 0.005 | 1 11% | 9 5% | 0 0% | 15 7% | NS | 16 5% | 9 7% | NS | |

| Others | 5 12% | 8 5% | 13 7% | 4 8% | NS | 17 6% | 12 8% | NS | 2 22% | 17 10% | 1 5% | 10 5% | NS | 19 6% | 11 9% | NS | |

| Discouraging factors | |||||||||||||||||

| High cost | 24 57% | 127 78% | 144 80% | 37 76% | p = 0.02 | 236 78% | 93 73% | NS | 7 78% | 138 80% | 36 77% | 147 73% | NS | 255 80% | 76 67% | p = 0.007 | |

| Fear of pain and surgery | 6 14% | 11 7% | 22 12% | 6 12% | NS | 32 11% | 12 10% | NS | 1 11% | 20 12% | 2 4% | 21 10% | NS | 36 11% | 9 8% | NS | |

| Fear of foreign body | 3 7% | 7 4% | 7 4% | 3 6% | NS | 10 3% | 9 7% | NS | 1 11% | 7 4% | 1 2% | 11 5% | NS | 13 4% | 7 6% | NS | |

| Long duration of treatment | 5 12% | 9 6% | 15 8% | 4 8% | NS | 22 7% | 11 9% | NS | 0 0% | 12 7% | 1 2% | 19 9% | NS | 23 7% | 10 9% | NS | |

| Medical complications | 15 36% | 30 19% | 43 24% | 10 20% | NS | 78 26% | 20 16% | p = 0.02 | 1 11% | 30 17% | 15 31% | 51 25% | NS | 70 22% | 29 26% | NS | |

| Hematomas and swelling | 1 2% | 4 2% | 8 4% | 5 10% | NS | 12 4% | 6 5% | NS | 2 22% | 8 5% | 2 4% | 6 3% | NS | 15 5% | 3 3% | NS | |

| My poor health is a contraindication | 5 12% | 11 7% | 20 11% | 7 14% | NS | 31 10% | 12 10% | NS | 3 33% | 20 12% | 5 11% | 15 7% | NS | 32 10% | 11 10% | NS | |

| No need to restore missing teeth | 1 2% | 20 12% | 12 7% | 4 8% | NS | 20 7% | 17 13% | p = 0.02 | 0 0% | 13 8% | 1 2% | 23 11% | NS | 19 6% | 17 15% | p = 0.002 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dolińska, E.; Węglarz, A.; Jaroma, W.; Kornowska, G.; Zapaśnik, Z.; Włodarczyk, P.; Wawryniuk, J.; Pietruska, M. Periodontal Patients’ Perceptions and Knowledge of Dental Implants—A Questionnaire Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164859

Dolińska E, Węglarz A, Jaroma W, Kornowska G, Zapaśnik Z, Włodarczyk P, Wawryniuk J, Pietruska M. Periodontal Patients’ Perceptions and Knowledge of Dental Implants—A Questionnaire Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(16):4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164859

Chicago/Turabian StyleDolińska, Ewa, Anna Węglarz, Weronika Jaroma, Gabriela Kornowska, Zuzanna Zapaśnik, Patrycja Włodarczyk, Jakub Wawryniuk, and Małgorzata Pietruska. 2024. "Periodontal Patients’ Perceptions and Knowledge of Dental Implants—A Questionnaire Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 16: 4859. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164859