Importance of Coping Strategies on Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

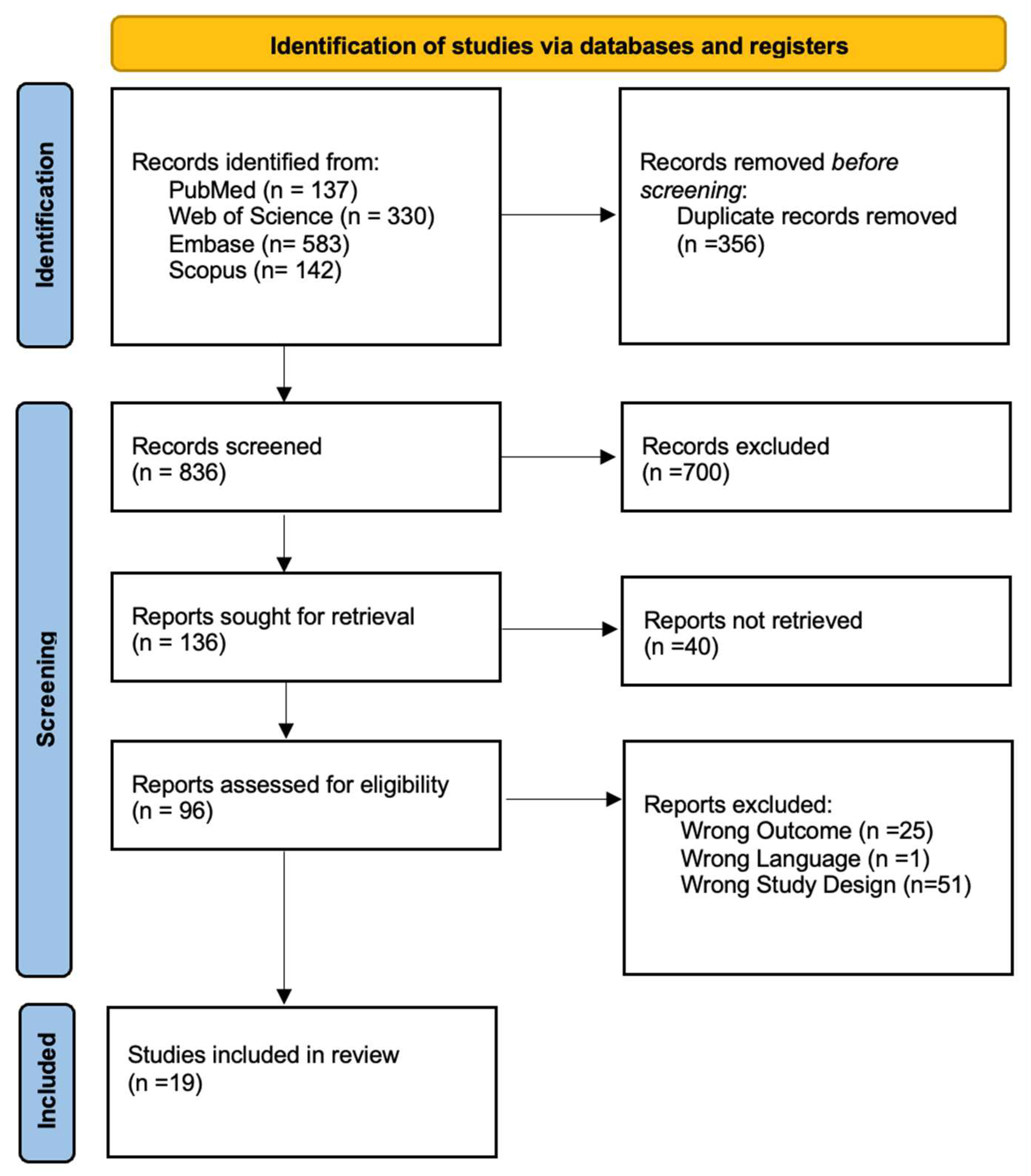

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.4. Risk of Bias within Individual Studies

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Evidence

3.2. Key Findings from Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

- Emotional factors

- Social and family support

- Stage and severity of disease

- Sociodemographic variables and personality traits

- Positive or negative coping strategies and quality of life

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonald, W.I.; Compston, A.; Edan, G.; Goodkin, D.; Hartung, H.; Lublin, F.D.; McFarland, H.F.; Paty, D.W.; Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; et al. Recommended Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Sclerosis: Guidelines from the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2001, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compston, A.; Coles, A. Multiple Sclerosis. The Lancet 2008, 372, 1502–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, P. Key Issues in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 2002, 59, S1–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: 2017 Revisions of the McDonald Criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingwell, E.; Marriott, J.J.; Jetté, N.; Pringsheim, T.; Makhani, N.; Morrow, S.A.; Fisk, J.D.; Evans, C.; Béland, S.G.; Kulaga, S.; et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Europe: A Systematic Review. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotgiu, S.; Pugliatti, M.; Sanna, A.; Sotgiu, A.; Castiglia, P.; Solinas, G.; Dolei, A.; Serra, C.; Bonetti, B.; Rosati, G. Multiple Sclerosis Complexity in Selected Populations: The Challenge of Sardinia, Insular Italy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2002, 9, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-J.; Chen, W.-W.; Zhang, X. Multiple Sclerosis: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatments. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 3163–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbo, H.F.; Gold, R.; Tintoré, M. Sex and Gender Issues in Multiple Sclerosis. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2013, 6, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.A.C.; Nóbrega, F.R.; Lopes, K.N.; Thuler, L.C.S.; Alvarenga, R.M.P. The Effect of Functional Limitations and Fatigue on the Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2009, 67, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Wahlig, E.; Bakshi, R.; Fishman, I.; Munschauer, F.; Zivadinov, R.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Predicting Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: Accounting for Physical Disability, Fatigue, Cognition, Mood Disorder, Personality, and Behavior Change. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 231, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschedijk, M.A.J.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J.; Klein, M.; van der Ploeg, E.; Collette, E.H.; Vleugels, L.; Pfennings, L.E.M.A.; Hoogervorst, E.L.J.; van der Ploeg, H.M.; Polman, C.H. Value of Health-Related Quality of Life to Predict Disability Course in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 2004, 63, 2046–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nortvedt, M.W.; Riise, T.; Myhr, K.-M.; Nyland, H.I. Quality of Life as a Predictor for Change in Disability in MS. Neurology 2000, 55, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowry, E.M.; Beheshtian, A.; Waubant, E.; Goodin, D.S.; Cree, B.A.; Qualley, P.; Lincoln, R.; George, M.F.; Gomez, R.; Hauser, S.L.; et al. Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Is Associated with Lesion Burden and Brain Volume Measures. Neurology 2009, 72, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, O.; Baumstarck-Barrau, K.; Simeoni, M.-C.; Auquier, P. Patient Characteristics and Determinants of Quality of Life in an International Population with Multiple Sclerosis: Assessment Using the MusiQoL and SF-36 Questionnaires. Mult. Scler. J. 2011, 17, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikula, P.; Nagyova, I.; Krokavcova, M.; Vitkova, M.; Rosenberger, J.; Szilasiova, J.; Gdovinova, Z.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. The Mediating Effect of Coping on the Association between Fatigue and Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Psychol. Health Med. 2015, 20, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, B.; Issa, Z.; Herlopian, A.; El Bejjani, M.; Khalifa, A.; Ghadieh, A.S.; Habib, R.H. Predictors of Quality of Life among Multiple Sclerosis Patients: A Comprehensive Analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2013, 20, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankhorst, G.J.; Jelles, F.; Smits, R.C.F.; Polman, C.H.; Kuik, D.J.; Pfennings, L.E.M.A.; Cohen, L.; van der Ploeg, H.M.; Ketelaer, P.; Vleugels, L. Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: The Disability and Impact Profile (DIP). J. Neurol. 1996, 243, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Navarro, J.; Benito-León, J.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Pardo, J.; Bowakim Dib, W.; Orts, E.; Belló, M. Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life of Spanish Caregivers of Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Situational Coping and Coping Dispositions in a Stressful Transaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiana, L.; Tomás, J.M.; Fernández, I.; Oliver, A. Predicting Well-Being Among the Elderly: The Role of Coping Strategies. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.D.M.; Valle, A.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G. Profiles of Psychological Well-Being and Coping Strategies among University Students. Front Psychol 2016, 7, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Goretti, B.; Portaccio, E.; Zipoli, V.; Hakiki, B.; Siracusa, G.; Sorbi, S.; Amato, M.P. Coping Strategies, Psychological Variables and Their Relationship with Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 30, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing Coping Strategies: A Theoretically Based Approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. The Relationship between Coping and Emotion: Implications for Theory and Research. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 26, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grech, L.B.; Kiropoulos, L.A.; Kirby, K.M.; Butler, E.; Paine, M.; Hester, R. Coping Mediates and Moderates the Relationship between Executive Functions and Psychological Adjustment in Multiple Sclerosis. Neuropsychology 2016, 30, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadden, M.H.; Guty, E.T.; Arnett, P.A. Cognitive Reserve Attenuates the Effect of Disability on Depression in Multiple Sclerosis. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2019, 34, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, E.; Koyanagi, A.; Caballero, F.; Domènech-Abella, J.; Miret, M.; Olaya, B.; Rico-Uribe, L.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Haro, J.M. Cognitive Reserve Is Associated with Quality of Life: A Population-Based Study. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 87, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Fletcher, B. The Relative Efficacy of Avoidant and Nonavoidant Coping Strategies: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 1985, 4, 249–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penley, J.A.; Tomaka, J.; Wiebe, J.S. The Association of Coping to Physical and Psychological Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Behav. Med. 2002, 25, 551–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-Regulation Strategies across Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M. A Longitudinal Study of Coping Strategies and Quality of Life Among People with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2006, 13, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M. Coping with Examination Stress: Resources, Strategies, Outcomes. Anxiety Stress Coping 1995, 8, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D. A Review of the PubMed PICO Tool: Using Evidence-Based Practice in Health Education. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brands, I.; Bol, Y.; Stapert, S.; Köhler, S.; van Heugten, C. Is the Effect of Coping Styles Disease Specific? Relationships with Emotional Distress and Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury and Multiple Sclerosis. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilski, M.; Gabryelski, J.; Brola, W.; Tomasz, T. Health-Related Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: Links to Acceptance, Coping Strategies and Disease Severity. Disabil Health J. 2019, 12, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanotti, S.; Cabral, N.; Eizaguirre, M.B.; Marinangeli, A.; Roman, M.S.; Alonso, R.; Silva, B.; Garcea, O. Coping Strategies: Seeking Personalized Care in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. A Patient Reported Measure–Coping Responses Inventory. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2021, 7, 205521732098758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerea, S.; Ghisi, M.; Pitteri, M.; Guandalini, M.; Strober, L.B.; Scozzari, S.; Crescenzo, F.; Calabrese, M. Coping Strategies and Their Impact on Quality of Life and Physical Disability of People with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikula, P.; Nagyova, I.; Krokavcova, M.; Vitkova, M.; Rosenberger, J.; Szilasiova, J.; Gdovinova, Z.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. Coping and Its Importance for Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnero Contentti, E.; López, P.A.; Alonso, R.; Eizaguirre, B.; Pettinicchi, J.P.; Tizio, S.; Tkachuk, V.; Caride, A. Coping Strategies Used by Patients with Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis from Argentina: Correlation with Quality of Life and Clinical Features. Neurol. Res. 2021, 43, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montel, S.R.; Bungener, C. Coping and Quality of Life in One Hundred and Thirty Five Subjects with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2007, 13, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grech, L.B.; Kiropoulos, L.A.; Kirby, K.M.; Butler, E.; Paine, M.; Hester, R. Target Coping Strategies for Interventions Aimed at Maximizing Psychosocial Adjustment in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2018, 20, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-González, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Conrad, R.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.Á. Coping with Multiple Sclerosis: Reconciling Significant Aspects of Health-Related Quality of Life. Psychol Health Med. 2023, 28, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, O.; Erbay, E.; Yıldırım, B.; Altındağ, Ö. Quality of Life, Coping, and Social Support in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Turk. J. Neurol. 2017, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ledesma, A.L.; Rodríguez-Méndez, A.J.; Gallardo-Vidal, L.S.; Trejo-Cruz, G.; García-Solís, P.; de Jesús Dávila-Esquivel, F. Coping Strategies and Quality of Life in Mexican Multiple Sclerosis Patients: Physical, Psychological and Social Factors Relationship. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 25, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farran, N.; Ammar, D.; Darwish, H. Quality of Life and Coping Strategies in Lebanese Multiple Sclerosis Patients: A Pilot Study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2016, 6, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, T.R.; Kuzu, D.; Kratz, A.L. Coping as a Moderator of Associations Between Symptoms and Functional and Affective Outcomes in the Daily Lives of Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2023, 57, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, F.; Bonanno, L.; Di Cara, M.; Rifici, C.; Sessa, E.; D’Aleo, G.; Lo Buono, V.; Venuti, G.; Bramanti, P.; Marino, S. Therapeutic Adherence and Coping Strategies in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Medicine 2019, 98, e16532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, D.; Krstic, Z.; Stojanovic, Z.; Kolundzija, K.; Stojkovic, M.; Dincic, E. The Influence of Personality Traits and Coping Strategies on the Quality of Life of Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Type of Multiple Sclerosis. Vojn. Pregl. 2021, 78, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, M.A.; Shireen, M.A.E.-M.; Hoda, A.B.; Mohamed, N.I.E.S. Personality Trait and Coping Strategies in Multiple Sclerosis: Neuropsychological and Radiological Correlation. Egypt J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2011, 48, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Calandri, E.; Graziano, F.; Borghi, M.; Bonino, S. Coping Strategies and Adjustment to Multiple Sclerosis among Recently Diagnosed Patients: The Mediating Role of Sense of Coherence. Clin Rehabil 2017, 31, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eizaguirre, M.B.; Ciufia, N.; Roman, M.S.; Martínez Canyazo, C.; Alonso, R.; Silva, B.; Pita, C.; Garcea, O.; Vanotti, S. Perceived Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: The Importance of Highlighting Its Impact on Quality of Life, Social Network and Cognition. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 199, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobentanz, I.S.; Asenbaum, S.; Vass, K.; Sauter, C.; Klosch, G.; Kollegger, H.; Kristoferitsch, W.; Zeitlhofer, J. Factors Influencing Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients: Disability, Depressive Mood, Fatigue and Sleep Quality. Acta Neurol. Scand 2004, 110, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadovnick, A.D.; Remick, R.A.; Allen, J.; Swartz, E.; Yee, I.M.L.; Eisen, K.; Farquhar, R.; Hashimoto, S.A.; Hooge, J.; Kastrukoff, L.F.; et al. Depression and Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 1996, 46, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorefice, L.; Fenu, G.; Frau, J.; Coghe, G.; Marrosu, M.G.; Cocco, E. The Burden of Multiple Sclerosis and Patients’ Coping Strategies. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018, 8, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assirelli, G.; Tosi, M. Education and Family Ties in Italy, France and Sweden. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2013, 3, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Tavoli, A.; Yazd Khasti, B.; Sedighimornani, N.; Zafar, M. Sexual Therapy for Women with Multiple Sclerosis and Its Impact on Quality of Life. Iran J. Psychiatry 2017, 12, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Imanpour Barough, S.; Riazi, H.; Keshavarz, Z.; Nasiri, M.; Montazeri, A. The Relationship between Coping Strategies with Sexual Satisfaction and Sexual Intimacy in Women with Multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari-Barzandig, R.; Sattarzadeh-Jahdi, N.; Meharabi, E.; Nourizadeh, R.; Najmi, L. Sexual Dysfunction in Iranian Azeri Women With Multiple Sclerosis: Levels and Correlates. Crescent J. Med. Biol. Sci. 2019, 6, 381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, K.; Rahnama, P.; Rafei, Z.; Ebrahimi-Aveh, S.M.; Montazeri, A. Factors Associated with Intimacy and Sexuality among Young Women with Multiple Sclerosis. Reprod Health 2020, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.A.; Tennant, A.; Mills, R.; Rog, D.; Ford, H.; Orchard, K. Sexual Functioning in Multiple Sclerosis: Relationships with Depression, Fatigue and Physical Function. Mult. Scler. J. 2017, 23, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakenham, K.I. Adjustment to Multiple Sclerosis: Application of a Stress and Coping Model. Health Psychol. 1999, 18, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Granella, F.; Lugaresi, A.; Martinelli, V.; Trojano, M.; Confalonieri, P.; Radice, D.; Solari, A. Anxiety and Depression in Multiple Sclerosis Patients around Diagnosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 307, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lode, K.; Bru, E.; Klevan, G.; Myhr, K.; Nyland, H.; Larsen, J. Depressive Symptoms and Coping in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, L.; Yardley, L.; Devereux, A.; Moss-Morris, R. Experiences of Adjusting to Early Stage Multiple Sclerosis. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, V.; De Giglio, L.; Prosperini, L.; Mancinelli, C.; De Angelis, F.; Barletta, V.; Pozzilli, C. Mood and Coping in Clinically Isolated Syndrome and Multiple Sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2014, 129, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, J.W.; Zautra, A.J.; Davis, M. Dimensions of Affect Relationships: Models and Their Integrative Implications. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.P.; Schlüter, D.K.; Young, C.A.; Mills, R.J.; Rog, D.J.; Ford, H.L.; Orchard, K. Use of Coping Strategies in Multiple Sclerosis: Association with Demographic and Disease-Related Characteristics✰. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 27, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommer, P.S.; König, N.; Sühnel, A.; Zettl, U.K. Coping Behavior in Multiple Sclerosis—Complementary and Alternative Medicine: A Cross-sectional Study. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2018, 24, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhofer-Polanyi, S.; Friedrich, F.; Löffler, S.; Rommer, P.S.; Gleiss, A.; Engelmaier, R.; Leutmezer, F.; Vyssoki, B. Health-Related Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: Temperament Outweighs EDSS. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbo, I.R.; Minacapelli, E.; Falautano, M.; Demontis, S.; Carpentras, G.; Pugliatti, M. Personality Traits Predict Perceived Health-Related Quality of Life in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2016, 22, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lode, K.; Larsen, J.P.; Bru, E.; Klevan, G.; Myhr, K.M.; Nyland, H. Patient Information and Coping Styles in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2007, 13, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goretti, B.; Portaccio, E.; Zipoli, V.; Hakiki, B.; Siracusa, G.; Sorbi, S.; Amato, M.P. Impact of Cognitive Impairment on Coping Strategies in Multiple Sclerosis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010, 112, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, M.P.; McKern, S.; McDonald, E. Coping and Psychological Adjustment among People with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 56, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.G.; Kroencke, D.C.; Denney, D.R. The Relationship between Disability and Depression in Multiple Sclerosis: The Role of Uncertainty, Coping, and Hope. Mult. Scler. J. 2001, 7, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinov, D.S.; Turner, A.P.; Williams, R.M. Coping among Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: Evaluating a Goodness-of-Fit Model. Rehabil. Psychol. 2015, 60, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.; Marijn Stok, F.; de Ridder, D.T.D. Feeding Your Feelings: Emotion Regulation Strategies and Emotional Eating. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull 2010, 36, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.; Sá, M.J. Cognitive Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Neurol 2012, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.M.; Leo, G.J.; Ellington, L.; Nauertz, T.; Bernardin, L.; Unverzagt, F. Cognitive Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 1991, 41, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, P.A.; Higginson, C.I.; Voss, W.D.; Randolph, J.J.; Grandey, A.A. Relationship Between Coping, Cognitive Dysfunction and Depression in Multiple Sclerosis. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2002, 16, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devy, R.; Lehert, P.; Varlan, E.; Genty, M.; Edan, G. Improving the Quality of Life of Multiple Sclerosis Patients through Coping Strategies in Routine Medical Practice. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 36, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, S.L.; Plow, M.; Packer, T.; Lipson, A.R.; Lehman, M.J. Psychoeducational Interventions for Caregivers of Persons With Multiple Sclerosis: Protocol for a Randomized Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e30617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseinpour, F.; Ghahari, S.; Motaharinezhad, F.; Binesh, M. Supportive Interventions for Caregivers of Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. MS Care 2023, 25, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnini, F.; Bosma, C.M.; Phillips, D.; Langer, E. Symptom Changes in Multiple Sclerosis Following Psychological Interventions: A Systematic Review. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, N.; Allen, J. Mindfulness of Movement as a Coping Strategy in Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2000, 22, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Design | Population | Disease Severity | EDSS | Education | Type of MS | Coping Test | QoL Test | Emotion Test | Cognitive Test | State | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brands [36] | Cross-sectional study | 310 (228 females) Mean age: 49 (SD 10.3) | Illness duration 9.5 | Mean 3.7 | Low: 77, medium: 109 High:123 | RRMS 209; PPMS 31; SPMS 68 | CIIST-T; CCS-EC | LiSat-9 | HADS | NA | South of Netherlands | CISS-A was positively associated with QoL |

| Calandri [52] | Cross-sectional study | 102 (63 females) M:35.8; SD: 11.9 | Mean disease duration 1.6 (SD: 0.8) | Score between 1 and 4 | Middle school diploma: 20; High school diploma: 59; Degree: 23 | RRMS 97; PPMS 1; SPMS 4 | CMSS | SF-12 Health Survey | SOC; PANAS | NA | Italy | Problem-solving emotional release and avoidance can be adaptive coping strategies for recently diagnosed MS patients |

| Cerea [39] | Cross-sectional study | 108 (84 female) mean age 38.09 (SD = 3.24) | Mean disease duration 6.35 | Median score 1.5 | 14.31 years | 99/108 RRMS; 9/108 SPMS | CRI-Adult | MSQoL-29 | DASS-21 | NA | Italy | Problem solving strategies positively impacted mental HRQoL |

| Carnero-Contentti [41] | Cross-sectional study | 249 (186 female) 38.6 (±10.7) | MS duration: year 7.3 ± 6.5 | Mean 1.98 ± 1.8 | No education: 32; Primary school: 61; High school: 64; Tertiary education University: 92 | RRMS | COPE-28 | MSIS-29 | FSS | NA | Argentina | Maladaptive coping strategies are associated with worst QoL |

| Corallo [49] | Observational study | 88 divided in two groups (injecting group 44 = age 48.30 ± 13.14; oral group: 44 = age 48.45 ± 12.68 years) | Injection group: 15.21 ± 8.3 Oral group: 12.83 ± 8.20 | NA | Injecting group: 11.33 ± 3.77 Oral group: 11.55 ± 3.12 | NA | COPE | MSQL-54 | Morisky Medication Adherence Scale | BRB-N | Italy | A correlation between therapeutic adherence, adaptive coping strategies, and mental health in the injective MS group |

| Farran [47] | Pilot Study | 34 (56% female) 36± 11 | Disease duration 9 ± 8 years | NA | NA | RRMS: 64.71; PPMS: 5.88; SPMS: 11.76; PRMS: 2.94; Patient did not know: 14.71 | WOCQ | MusiQoL | BDI-II; BAI; FSS; SPS. | NA | Lebanon | Positive coping strategies are associated with better QoL and lower psychological distress, while negative strategies, particularly escape avoidance, are linked to poorer outcomes. |

| Gil-González [44] | Longitudinal study | 314 (213 female) mean age 45.31 years (±10.77), | Months since diagnosis 145.68 | 3.17 ±1.92 | Primary education: 44 Secondary education: 102 University of higher: 168 | Remittent 272 (86.6) Progressive: 42 (13.4) | COPE-28 | SF-12 | MPSS | NA | Spain | Reducing dysfunctional coping strategies and promoting cognitive reframing may improve HRQOL in individuals with MS. |

| Goretti [23] | Observational study | 104 (72 female) 45.3 ± 10.9 years | Mean disease duration 17.9 ± 13.2, | mean EDSS 2.8 ± 2.0 | mean education 12.1 ± 3.1, | 73 patients RRMS, 26 SPMS, 5 PPMS | COPE-NVI | MSQOL-54 | BDI, STAI-Y, EPQ, FSS | NA | Italy | MS people use more frequently avoiding strategies. Depression and anxiety impact negatively QoL |

| Grech [43] | Cross-sectional study | 107 (83 female) 48.80 ± 11.10 | Time since diagnosis 9.82 ± 7.46 | 2.90 ± 2.31 | Secondary 30 (28.04); College 21 (19.63); Undergraduate 34 (31.77); Postgraduate 22 (20.56) | RRMS: 83; SPMS 24 | 60-item COPE inventory | MSQOL-54 | BDI, STAY, Daily Hassles Scale, | NA | Australia | Depression, stress frequency, trait anxiety, and mental health QOL were influenced by both adaptive and maladaptive coping style |

| Hernandez-Ledersma [46] | Cross-sectional study | 26 mean age 39.2 ± 10.6 years | Mean age at diagnosis was 32.7 ± 9.7 years | NA | Completed Middle school: 11.5%; High school diploma: 19.2%; Technical degree: 7.7%; College degree: 57.7%; Postgraduate degree: 3.8% | RRMS: 50%; PPMS: 11.5%; SPMS: 7.7%; Unclassified MS: 30.8% | Spanish version of CSI | WHOQOL-BREF | BDI, BAI, FSS, FF-SIL, Duke-UNC-11 | NA | Mexico | Positive coping strategies, along with a supportive psycho-social environment and good physical health, improve QoL perception. |

| Krstić [50] | Cross-sectional study | 66 (34 female), age 41.6 ± 7.1 | Duration of illness 8.1 ± 5.1 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 8–12 years: 4 patients (6%); 12–16 years: 46 patients (70.1%); More than 16 years: 16 patients (23.9%) | RRMS | CSI | MSQOL-54 | NEO-PI-R | NA | Serbia | Higher neuroticism and passive coping strategies reduce the QoL |

| McCabe [32] | Longitudinal study | Time 1: 381 MS people (237 female, mean age = 45.18 years). 291 HP; Time 2: 283 (186 female) and 239 HP | NA | NA | NA | NA | WOCQ | WHOQOL | NA | NA | Australia | Social support, focusing on the positive, and wishful thinking predict QOL |

| Mikula [40] | Cross sectional study | 113 (87 female) 40.82 ± 9.22 | Disease duration 8.40 | 3.31 ± 1.37 | NA | RRMS 96; SPMS 17. | CSE | SF-36 | NA | NA | Slovakia | Managing unpleasant emotions and thoughts, play a crucial role in improving the mental well-being of MS patients. |

| Montel [42] | Cross-sectional study | 135 (66 female) 44.3 (11.8) | Disease duration 8.7 (6.8) | Mean score 3.8. RRMS: 1.8; SPMS: 5.4; PPMS: 4.6. | NA | 53 RRMS; 53 SPMS; 29 PPMS | WCC; CHIP; | SEP 59 | MADRS; EHD; HAMA; | MINI; FAB | France | SPMS patients tend to rely heavily on emotional coping strategies, whereas PPMS patients utilize more instrumental strategies. |

| Nada [51] | Prospective case-control study | 40 (24 female) 33.8 ± 8.91; 20 HC (12 female) | 6.67 ± 4.03 | PPMS: Mean EDSS = 5.9 ± 1.2; RRM: Mean EDSS = 4.3 ± 0.8; Total MS group: Mean EDSS = 4.96 ± 1.12 | NA | 22 RRMS; 18 PPMS | Coping processes Scale, EPQ | QoL | HADS | MMSE | Egypt | Exercising restraint and positive reinterpretation have proven to be more effective in enhancing patients’ QoL |

| Vanotti [38] | Cross-sectional study | 90 (59 female) mean age 40.97 ± 12.85 | Disease evolution 10.76 ± 9.72 years | 2.48 ± 1.79 | 13.46 ± 3.93 | RRMS: 95.56%; PPMS: 2.22%; SPMS: 2.22%. | CRI-A | MusiQol | BDI, Fatigue severity scale | NA | Argentine | Emotion-focused coping strategies were negatively correlated with QoL |

| Wilski [37] | Cross-sectional study | 382 (256 female) 46.4 ± 11.9 (18–82) | NA | Mean EDSS Score: 4.4 ± 1.7 (range: 1–8.5) | Primary/Vocational: 25.1%; Secondary: 43.2%; Higher: 31.7% | RRMS: 158; PPMS: 88; SPMS:70; PRMS: 33; Unknown type: 33. | CISS | MSIS-29 | NA | NA | Poland | Younger MS patients with higher acceptance, using problem-solving and avoidance coping strategies, had longer disease duration and better HRQoL. |

| Zengin [45] | Cross-sectional study | 214 (126 female) | NA | NA | Primary school and less: 31; Secondary school: 26; High school: 64; Bachelor’s degree: 67; Postgraduate: 20 | NA | COPE | WHOWOL-BREF | NA | NA | Turkey | Problem-focused coping strategies were positively correlated with QoL |

| Valentine [48] | Cross-sectional study | 102 average age 44.68 years. | Average MS disease duration was 9.26 years (SD = 8.25 years). | NA | Primary school and less: 16.8%; Secondary school: 12.1%; High school: 29.9%; Bachelor’s degree: 31.3%; Postgraduate: 9.3% | NA | COPE | PAWB | NA | NA | Turkey | Problem-focused coping strategies were positively correlated with QoL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Culicetto, L.; Lo Buono, V.; Donato, S.; La Tona, A.; Cusumano, A.M.S.; Corello, G.M.; Sessa, E.; Rifici, C.; D’Aleo, G.; Quartarone, A.; et al. Importance of Coping Strategies on Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185505

Culicetto L, Lo Buono V, Donato S, La Tona A, Cusumano AMS, Corello GM, Sessa E, Rifici C, D’Aleo G, Quartarone A, et al. Importance of Coping Strategies on Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(18):5505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185505

Chicago/Turabian StyleCulicetto, Laura, Viviana Lo Buono, Sofia Donato, Antonino La Tona, Anita Maria Sophia Cusumano, Graziana Marika Corello, Edoardo Sessa, Carmela Rifici, Giangaetano D’Aleo, Angelo Quartarone, and et al. 2024. "Importance of Coping Strategies on Quality of Life in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 18: 5505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185505