Cognitive Stimulation in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

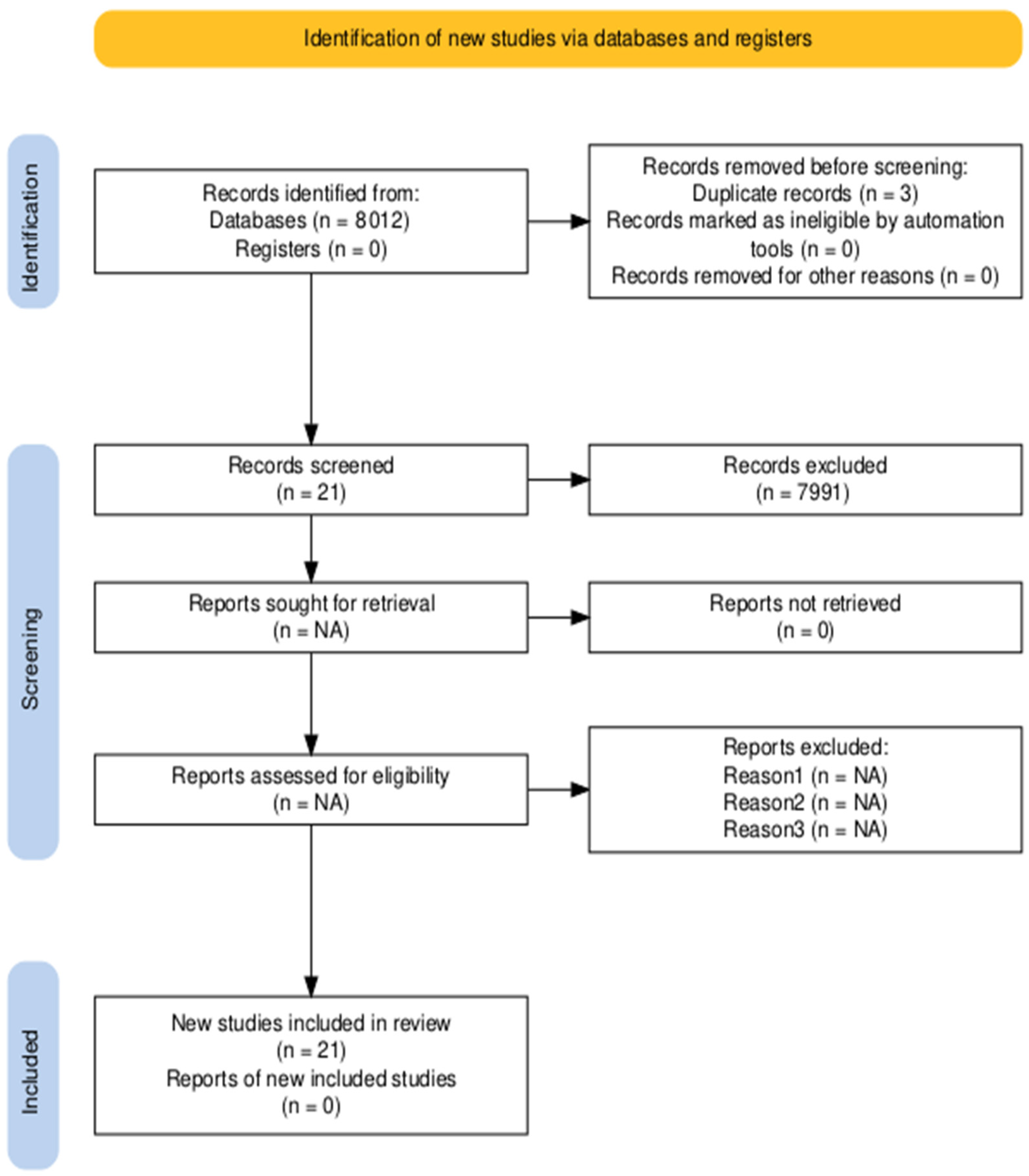

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion criteria (PICOS framework):

- Population: Older adults (male and female) with diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder due to dementia who live in the community and/or nursing homes.

- Interventions: Cognitive stimulation for older adults with dementia.

- Comparison with another type of non-pharmacological intervention or with a control group.

- Outcome measures: Cognitive benefits, quality of life of the patient and caregiver, executive functions, and the relationship between the user and their caregiver.

- Study design: Controlled trials, randomised clinical trials, non-randomised clinical trials, and pilot studies.

- Studies published from 2012 to 2025.

- Publications in English or Spanish.

- Exclusion criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Methodological Quality Analysis

3. Results

| Authors | Objective | Intervention | Duration | Outcome Measures | Assessment Tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al. [11] | To study the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a cognitive stimulation games intervention on cognitive functions. | N = 30 Intervention group (n = 15): cognitive stimulation through CoS-Play. Control group (n = 15): social activities that followed a similar pattern to the intervention group. | 8 weekly sessions of 45 to 60 min. | Cognitive functions. Verbal fluency. | MoCA FOME FVFT Questions to centre staff | The results showed significant differences from the intervention group to the control group with respect to the functions of memory storage and retrieval, with a mean of 5.92 in the intervention group and 4.12 in the control group. In terms of global cognition and verbal fluency no differences were found between the groups. Acceptance and integration was good, but regarding practicality they considered that a lot of manpower was needed. |

| Alves et al. [12] | To develop a relevant intervention, enhance cognitive function, foster social engagement, and improve participants’ quality of life. | N = 20 Intervention group (n = 10): full cognitive stimulation programme. Waiting list group (n = 10): cognitive stimulation but shorter. | 7 sessions of 1 h each, during 1 month and a half. Each session had 2 levels of difficulty. | Cognitive functioning. Social interaction and engagement. Quality of life. | MMSE ADAS IADL Nonpharmacologic all Therapy Experience Scale. | The results show that the waiting list group showed higher global cognitive functioning than the intervention group (p = 0.03). For the other variables, no significant differences were found between the two groups. |

| Coen et al. [13] | To evaluate the efficacy of cognitive stimulation therapy, replicating the methods of Spector et al. in the British Journal of Psychiatry. | N = 27 Intervention group (n = 14): cognitive stimulation in conjunction with usual therapies. Control group (n = 13): continued to receive usual therapies. | 14 sessions of 45 min, twice a week for seven weeks. | Cognitive performance. Quality of life. | MMSE WHOQOL | The intervention group improved cognitive performance compared to the control group (p = 0.013). Regarding quality of life, no significant differences were found between the groups (p = 0.055). |

| Katsuo Yamanaka et al. [14] | To develop and examine whether the Japanese version of group cognitive stimulation therapy produces improvement in cognitive function and quality of life in people with mild to moderate dementia. | N = 56 Intervention group (n = 26): Japanese version of group cognitive stimulation therapy. Control group (n = 30): usual activities. | 14 sessions, twice a week for 7 weeks. | Cognition. Quality of life. Mood. | COGNISTAT. MMSEEQ-5D QoL-AD Facial mood scale | The results showed significant improvements in cognitive functions and mood in the intervention group compared to the control group (p < 0.01). Quality of life improved in the intervention group when rated by caregivers, although there was no improvement when rated by the participants themselves. |

| Kolanowski et al. [15]. | To analyse whether cognitive stimulation activities reduce the duration and severity of delirium and improve cognitive and physical function to a greater extent than usual care. | N = 283 Intervention group (n = 141): cognitive stimulation. Control group (n = 142): usual treatment. | 30 days | Duration and severity of delirium. Cognitive function. Physical function. | CAM DRS BI DF, MOC CLOX | The results of the study showed that the severity and duration of delirium were similar in both groups (p = 0.37). While improvements in constructive praxis (p = 0.0003) and executive function (p = 0.03) were seen in the intervention group compared to the control group. The length of stay was also shorter in the intervention group than in the control group (p = 0.01). |

| Aguirre et al. [16] | To study the effect of cognitive stimulation therapy on the general health status of caregivers of people with dementia living in the community who attend the intervention. | N = 85 Intervention group (n = 41): users with dementia included here received cognitive stimulation. Control group (n = 44): users continued with usual care. | 7 weeks, 14 sessions of standard cognitive stimulation therapy. Subsequently, 24 weeks of maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy | General well being state | EQ-5D (for carers). SF-12 (for self-assessment of users). | The results showed that there is no evidence between the two groups that cognitive stimulation produces improvements in the caregivers of family members with dementia attending the intervention. |

| Vasiliki Orgeta et al. [25] | To assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of individual caregiver-led cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia and their family caregivers, compared to treatment as usual. | N = 356 Individuals were randomly assigned to each group. Intervention group (n = 180): cognitive stimulation at home led by their caregiver. Control group (n = 176): treatment as usual led by their caregiver. | 3 sessions of 30 min (each) per week and for 25 weeks | Cognition. Quality of life and relationships. Behavioural, psychological and depressive symptoms. Activities of daily living. | SF-12 EQ-5D. ADAS-Cog. QoL-AD | The intervention group showed improved relationships with caregivers (p = 0.02), who also reported better health-related quality of life (p = 0.01) and communication. Qualitative data suggested fewer depressive symptoms among caregivers attending more sessions. No significant differences were found for other variables. The therapy also led to greater health gains and cost savings. |

| Martin Orrell et al. [17] | To evaluate the effectiveness of a caregiver-led, home-based individual cognitive stimulation therapy programme in improving cognition and quality of life of the person with dementia and the mental and physical health (well-being) of the caregiver. | N = 356 Intervention group (n = 180): they received cognitive stimulation led by their usual caregiver. Control group (n = 176): they continued with the usual therapies but directed by their caregiver. | 3 sessions of 30 min per week for 25 weeks (75 sessions in total). | Cognition. Self-reported quality of life. General health status of the caregiver. Quality of the relationship with the caregiver. | ADAS-Cog. QoL-AD SF-12 EQ-5D | The results showed that people with dementia in the intervention group improved the quality of their relationship with their caregiver (p = 0.02) and also the caregivers in this group improved their health-related quality of life (p = 0.01) compared to the control group. In the rest of the variables there were no significant differences between the two groups. |

| DeokJu Kim [18] | To determine the effectiveness of reconverted occupational therapy programmes. | N = 35 Experimental group (n = 18): received the reminiscence-based occupational therapy programme. Control group (n = 17): continued to receive the regular activities offered by their day centres. | 24 sessions, 5 times a week and for 1 h per session. | Cognitive functions. Depression. Quality of life. Activities of daily living. | FIM. K-MMSE. SMCQ GDS-SF-K GQOL-D. | The results showed that the experimental group had an improvement in cognitive functions (p < 0.05), a reduction in depression (p < 0.05) and a higher quality of life (p < 0.01) compared to the control group. |

| Justo- Henriques et al. [23] | To assess the efficacy, feasibility and acceptability of a long-term individual cognitive stimulation intervention for people with mild neurocognitive impairment. | N = 30 Intervention group (n = 15): cognitive stimulation. Control group (n = 15): 15 routine interventions. | 88 individual sessions of 45 min each, twice a week. | Cognitive performance. Depressive symptoms. Level of autonomy in activities of daily living. | MMSE. MoCA GDSBI. Questionnaire of sociodemographic characterisation. Registration sheet. | The results of the study showed that the intervention group obtained a significant improvement in global cognitive performance (d = 0.83) in particular in the area of language and less depressive symptomatology (d = 0.93) compared to the control group. No differences were found between the two groups in the autonomy in performing activities of daily living (p = 0.34). Only 6.7% of the participants dropped out of the study and of the intervention group the participants attended an average of 83 ± 12.1 sessions. |

| Cintoli et al. [27] | Evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a cognitive stimulation intervention for dementia patients, contributing to the development of more accessible and personalised therapeutic strategies | N = 19 dementia patients, with 12 participating in in-person treatment and 7 engaged remotely. Cognitive stimulation protocol: memory, attention, and problem-solving exercises, guided by a clinical psychologist. The protocol was adapted to an online format, maintaining the characteristics of the in-person implementation. | Eight weekly, 1 h individual sessions | Cognitive performance. Level of autonomy in activities of daily living. Satisfaction for both patients and caregivers. | MMSE ADL Scale, IADL Scale VAS Likert scale | No differences were found at the beginning or end of the study inoverall cognitive functioning or in the ability to performactivities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in either group. The Cognitive stimulation delivered both in-person and via videoconferencing, is feasible and well-received by both patients and caregivers. |

| Pérez-Sáez et al. [28] | Adaptation of the cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) from the United Kingdom to the Spanish cultural context, implementing sessions. | N = 6 Intervention adapted from the cognitive stimulation therapy Spain (CST-ES) and maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy MC Spain (ST-ES) CST programme consists of 14 45 min sessions that are conducted twice a week for 7 weeks MCST program that includes 24 additional sessions is delivered after the 7 weeks of CST, at a rate of one session per week. | 14 45 min sessions that are conducted twice a week for 7 weeks | Cognitive performance. Level of autonomy in activities of daily living. Depressive symptoms. Quality of life. | MMSE, CAMCOG-R, GDS-15, QoL-AD BI IADL | The results are similar to those of other cultural adaptations, showing positive changes to general cognition and quality of life following the implementation of CST. However, no improvements were observed in activities of daily living. After the MCST-ES programme, cognitive scores remained stable, and there was a non-significant decline in quality of life. |

| Spector et al. [19] | Assess the feasibility and acceptability of online cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) or “virtual” cognitive stimulation therapy (vCST). | N = 46 Intervention group (n = 24) vCST: involved 14 60 min group sessions delivered twice a week for 7 weeks. Control group treatment as usual (TAU) (n = 22). | 14 60-min group sessions delivered twice a week for 7 weeks. | Cognition. Quality of life. Depression. | ADAS-Cog GDS-15 MOCA BLIND QoL-AD | No statistically significant differences were found between the vCST and treatment as usual groups in any of the outcome measures. Although at a qualitative level, there were reports of improvements in the outcomes. |

| Piras et al. [26] | To compare the effectiveness of the Italian Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST-IT), applied in a previous multicenter controlled clinical trial, across two distinct cohorts of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in the mild-to-moderate stage | The Italian adaptation of the original CST protocol developed by Spector and colleagues N = 58 Alzheimer disease Group n = 30 Vascular Dementia Group n = 27 | 20 sessions over a period of 23 weeks. | General cognitive functioning Communicative abilities Mood Behaviour Perceived quality of life | MMSE ADAS- Cog NLT CSDD NPI QoL-AD | CST-IT achieved clinically significant improvements to general cognition and communicative abilities. Depressive symptoms decreased more notably in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, while quality of life showed a slight improvement in those with vascular dementia. Improvements in narrative abilities were observed in patients with vascular dementia. Post-intervention gains in depressive symptoms persisted in Alzheimer’s disease but not in vascular dementia, although the benefits in quality of life remained stable in the latter group. |

| Bertrand et al. [24] | Explore the impact of a Brazilian adapted version of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST-Brasil) on the level of awareness.t | N = 47 Experimental Group: cognitive stimulation therapy n = 24. Control Group: treatment as usual (TAU) N = 23. | 7 weeks | Metacognitive: level of awareness. | ASPIDD | Awareness of the disease increased in both groups. However, only those who received Cognitive Stimulation Therapy showed improvements in awareness of their cognitive abilities |

| Dudley et al. [29] | Adaptation of the cognitive stimulation therapy(CST) from the United Kingdom to the Māori cultural context, implementing sessions | N = 15 Two CST programmes: the 14 45 min sessions that are conducted twice a week for 7 weeks. | 7 weeks | Cognition. Quality of life. | RUDAS WHOQOL-BREF | There was a statistically significant improvement in cognition (RUDAS: pre = 17.7, post = 19.4, p = 0.003) and in the WHOQOL subscales of physical (pre = 75.9, post = 88.5, p = 0.003), psychological (pre = 72.7, post = 81.3, p = 0.024) and environment (pre 80.6, post = 88.0, p = 0.006). |

| Cunha [30] | To evaluate the effectiveness of individual cognitive stimulation interventions | N = 21 Three sessions per week for a total of 36 sessions the “Making a Difference 3”. An Individual Cognitive Stimulation Program. | 12 weeks | Cognition. Quality of life neuropsychiatric symptoms of older adults with dementia. Quality of the relationship between the older adult with dementia and the caregiver. | GDS-15 QCPR QoL-AD SLUMS NPI–Q | There were statistically significant improvements in neuropsychiatric symptoms (p = 0.042) and cognition (p = 0.038) after the programme was administered. |

| Justo-Henriques [20] | To assess the efficacy of a long-term individual cognitive stimulation intervention on people with mild neurocognitive disorder | N = 82 Cognitive stimulation intervention group n = 41 Control group n = 41 | 88 individual format sessions of approximately 45 min, twice per week. | Cognition. Depressive symptomatology. Autonomy level in activities of daily living. | MMSE MoCA GDS-15 BI | Significant improvement on cognition and depressive symptomatology in the intervention group compared to the control group were found intra-intervention (6 months) and post-intervention (12 months). Younger participants and those with better cognitive status at the beginning of the study achieved better results. |

| Coşkun and Çuhadar [21] | Evaluate the effects of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy on activities of daily living, depression, and life satisfaction in older adults with dementia in nursing homes. | N = 60 Intervention group n = 30: Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. Control group n = 30: received only two sessions in week 2, and they continued their daily lives and routine treatments. | 9 weeks. 14 sessions approximately 45 min | Activities of daily living. Depression. Life satisfaction. | SMMSE BADLIIADLS CSDD SWLS | Statistically significant improvements were observed in the intervention group in BADLI, IADLS, and CSDD, both in the post-test and in the follow-up. While Life satisfaction showed statistically significant improvements only in the post-test. |

| Atay, E., & Bahadır Yılmaz, E [22]. | Determine the effect of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) on apathy, loneliness, anxiety, and activities of daily living of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. | N = 52 Intervention group n = 26: Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. Control group n = 26: in routine unstructured music, sports, and art activities at the centre. | 14 sessions, twice a week. | Apathy. Loneliness. Anxiety. Activities of daily living. | MMSE AES-C UCLA UCLA-SF GAS DAD | A significant reduction in apathy, loneliness, and anxiety was observed in the intervention group compared to the control group. Following the application of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy, significant differences were observed in the intervention group on the AES-C, UCLA, GAS and DAD |

| Zubatsky et al. [31] | Explored differences in cognitive function, mood, and quality of life from CST groups both community and residential-based groups. | N = 258 From academic and rural, hospital-based settings in Missouri received s Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST). | 7 weeks, each session was 1 h. 14 Sessions | Cognitive function. Mood. Quality of life. | SLUMSCSDD QOL-AD | Following the intervention, cognitive function improved in both the community and residential groups. However, participants living in the community showed significant improvements in mood. |

Methodological Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schönborn, R. WHO-Definition von Demenz. In Demenzsensible Psychosoziale Intervention; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 5–6. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-658-20868-4_2 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Villarejo, A.; Eimil, M.; Llamas, S.; Llanero, M.; López, C.; Prieto, C. Report by the Spanish Foundation of the Brain on the social impact of Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia. Neurologia 2021, 36, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitrini, R.; Dozzi, S.M. Demencia: Definición y clasificación. Rev. Neuropsicol. Neuropsiquiatría Neurocienc. 2012, 12, 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M. Aprobado por la FDA el nuevo tratamiento de anticuerpos dirigidos contra las placas de β-amiloide en las fases iniciales de la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Actual. Farmacol. Ter. 2024, 22, 227–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.; Sánchez, X.A.; Angulo, C.N.; Robert, P.; Arce, J.S.; Pérez, Á.G. Terapias emergentes para la enfermedad de Alzheimer: Revisión sistemática de anticuerpos anti-amiloide y mecanismos alternativos. Rev. Científica Salud Desarro. Hum. 2025, 6, 1048–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, N. Terapia ocupacional. Intervención domiciliaria en fase inicial de Alzheimer. Rev. Para Prof. Salud 2021, 4, 28–55. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo, V.; Arroyo, M.R.; Portero, M.; Ruiz, J.M. Efectos de la terapia no farmacológica en el envejecimiento normal y el deterioro cognitivo: Consideraciones sobre los objetivos terapéuticos. Neurología 2013, 28, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilla, R.; Martínez, R.M.; Fernández, J. Eficacia de la terapia ocupacional y otras terapias no farmacológicas en el deterioro cognitivo y la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2016, 51, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Catalá-López, F.; Moher, D. La extensión de la declaración PRISMA para revisiones sistemáticas que incorporan metaanálisis en red: PRISMA-NMA. Med. Clin. 2016, 147, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escala PEDro [Internet]. PEDro—Physiotherapy Evidence Database. PEDro. 2016. Available online: https://pedro.org.au/spanish/resources/pedro-scale/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Cheung, D.S.K.; Li, B.; Lai, D.W.L.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Yu, C.T.K.; Tsang, K.T. Cognitive Stimulating Play Intervention for Dementia: A Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2019, 34, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.; Alves-Costa, F.; Magalhães, R.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Sampaio, A. Cognitive stimulation for Portuguese older adults with cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial of efficacy, comparative duration, feasibility, and experiential relevance. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2014, 29, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coen, R.F.; Flynn, B.; Rigney, E.; O’Connor, E.; Fitzgerald, L.; Murray, C.; Dunleavy, C.; McDonald, M.; Delaney, D.; Merriman, N.; et al. Efficacy of a cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2011, 28, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, K.; Kawano, Y.; Noguchi, D.; Nakaaki, S.; Watanabe, N.; Amano, T.; Spector, A. Effects of cognitive stimulation therapy Japanese version (CST-J) for people with dementia: A single-blind, controlled clinical trial. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, A.; Fick, D.; Litaker, M.; Mulhall, P.; Clare, L.; Hill, N.; Mogle, J.; Boustani, M.; Gill, D.; Yevchak-Sillner, A. Effect of Cognitively Stimulating Activities for the Symptom Management of Delirium Superimposed on Dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial HHS Public Access. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2424–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, E.; Hoare, Z.; Spector, A.; Woods, R.T.; Orrell, M. The effects of a Cognitive Stimulation Therapy [CST] programme for people with dementia on family caregivers’ health. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrell, M.; Yates, L.; Leung, P.; Kang, S.; Hoare, Z.; Whitaker, C.; Burns, A.; Knapp, M.; Leroi, I.; Moniz-Cook, E.; et al. The impact of individual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (iCST) on cognition, quality of life, caregiver health, and family relationships in dementia: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D. The Effects of a Recollection-Based Occupational Therapy Program of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Occup. Ther. Int. 2020, 2020, 6305727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, A.; Abdul, N.; Stott, J.; Fisher, E.; Hui, E.; Perkins, L.; Leung, W.G.; Evans, R.; Wong, G.; Felstead, C. Virtual Group Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for Dementia: Mixed-Methods Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnae063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justo, S.; Pérez, E.; Marques, A.; Carvalho, J. Effectiveness of an individual cognitive stimulation program for older adults with cognitive impairment. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2023, 30, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, E.; Çuhadar, D. The effect of cognitive stimulation therapy on daily life activities, depression and life satisfaction of older adults living with dementia in nursing home: Randomized controlled trial. Dementia 2025, 24, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, E.; Bahadır, E. The effect of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) on apathy, loneliness, anxiety and activities of daily living in older people with Alzheimer’s disease: Randomized control study. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo-Henriques, S.I.; Marques-Castro, A.E.; Otero, P.; Vázquez, F.L.; Torres, Á.J. Longterm individual cognitive stimulation program in patients with mild neurocognitive disorder: A pilot study. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 68, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, E.; Marinho, V.; Naylor, R.; Bomilcar, I.; Laks, J.; Aimee Spector, A.; Mograbi, D.C. Metacognitive Improvements Following Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for People with Dementia: Evidence from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Gerontol. 2023, 46, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeta, V.; Leung, P.; Yates, L.; Kang, S.; Hoare, Z.; Henderson, C.; Whitaker, C.; Burns, A.; Knapp, M.; Leroi, I.; et al. Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: A clinical effectiveness and costeffectiveness pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol. Assess 2015, 19, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, F.; Carbone, E.; Domenicucci, R.; Sella, E.; Borella, E. Does Cognitive Stimulation Therapy show similar efficacy in individuals with mild-to-moderate dementia from varying etiologies? An examination comparing its effectiveness in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2024, 24, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintoli, S.; Spadoni, G.; Giuliani, V.; Nicoletti, V.; Prete, E.; Frosini, D.; Ceravolo, R.; Tognoni, G. A pilot study investigating the effectiveness, appreciation, and feasibility of a cognitive stimulation program in dementia patients: Online versus face-to-face. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1561157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.; Aguirre, E.; Tofiño, M.; Rodríguez, T.; Peláez, B. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy-Spain (CST-ES): Cultural Adaptation Process and Pilot Study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2025, 40, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, M.; Peri, K.; Kake, T.; Cheung, G. Cultural Adaptation of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for Māori with Dementia (CST-Māori). J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2025, 40, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, F.; Simoes, D.; Moreira, S.; Mota, C.; Santos, P.; Assunção, I.; Silva, R.C.G. Effectiveness of an individual cognitive stimulation program for older adults with cognitive impairment. Rev. Enfermagem. 2024, 3, e35987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubatsky, M.; Khoo, Y.; Lundy, J.; Blessing, D.; Berg-Weger, M.; Hayden, D.; Morley, J.E. Comparisons of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy Between Community Versus Hospital-Based Settings: A Multi-Site Study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, B.; Rai, H.K.; Elliott, E.; Aguirre, E.; Orrell, M.; Spector, A. Estimulación cognitiva para mejorar el funcionamiento cognitivo en personas con demencia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1, CD005562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaba, S.; Esper, R. Estimulación cognitiva: Una revisión neuropsicológica. Therapeía 2014, 6, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz, S. Eficacia de un Programa de Estimulación Cognitiva en un grupo de personas con probable Enfermedad de Alzheimer en fase leve. Estudio Piloto. Rev. Discapac. Clínica Neurocienc. 2015, 2, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.S.; Bratkovich, K.L. Assessment and cognitive-behaviorally oriented interventions for older adults with dementia. In Cognitive Behavior Therapy with Older Adults: Innovations Across Care Settings; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 219–261. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-06946-008 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Spector, A.; Thorgrimsen, L.; Woods, B.; Royan, L.; Davies, S.; Butterworth, M.; Orrell, M. Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamanca, R.M.V.; Pérez, C.L. Calidad de vida objetiva, optimismo y variables socio-jurídicas, predictivos de la calidad de vida subjetiva en Colombianos desmovilizados. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2011, 29, 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolote, J. Ayuda Para Cuidadores de Personas Con Demencia; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994; Volume 14, p. 23. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/u/eshelpforcaregivers.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Freund, Y.; Eriksdotter, M.; Cederholm, T.; Basun, H.; Faxén, G.; Garlind, A.; Vedin, I.; Vessby, B.; Wahlund, L.-O.; Palmblad, J. Omega-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study: A randomized double-blind trial. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, M.J.; López-Arza, M.V.G.; Ardila, E.M.G.; Domínguez, T.R.; Mansilla, J.R. Effects of a cognitive rehabilitation programme on the independence performing activities of daily living of persons with dementia—A pilot randomized controlled trial. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, F.; Morales Gabardino, J.A. Demencia. FMC Form. Medica Contin. Aten. Primaria 2011, 18, 646–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Words | Databases | Total | Excluded | Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “cognitive stimulation and dementia” | PUBMED | 171 | 158 | 13 |

| “cognitive stimulation and dementia” | SCIENCEDIRECT | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| “cognitive stimulation and dementia” | OTSEEKER | 35 | 35 | 0 |

| “estimulación cognitiva y demencia” | DIALNET | 107 | 107 | 0 |

| “cognitive stimulation and dementia” | SCOPUS | 3877 | 3.871 | 6 |

| < | ||||

| “cognitive stimulation and occupational therapy” | PUBMED | 34 | 34 | 0 |

| “cognitive stimulation and occupational therapy” | SCIENCEDIRECT | 1.919 | 1.918 | 1 |

| “cognitive stimulation and occupational therapy” | OTSEEEKER | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| “estimulación cognitiva y terapia ocupacional” | DIALNET | 33 | 33 | 0 |

| “cognitive stimulation and occupational therapy” | SCOPUS | 1.833 | 1833 | 0 |

| Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguirre et al. [16] (2014) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6/11 |

| Cheung et al. [11] (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Orgeta et al. [25] (2015) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7/11 |

| Alves et al. [12] (2014) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Orrell et al. [17] (2017) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9/11 |

| Coen et al. [13] (2011) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5/11 |

| Yamanaka et al. [14] (2013) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7/11 |

| Kim [18] (2020) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5/11 |

| Kolanowski [15] (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9/11 |

| Justo-Henriques [23] (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Spector et al. [19] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Piras et al. [26] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Bertrand et al. [24] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Justo et al. [20] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7/11 |

| Coşkun et al. [21] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8/11 |

| Atay. [22] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9/11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Palomares, M.; Montero-Barrero, O.; Garrido-Ardila, E.M.; Gibello-Rufo, A.; González-Sánchez, B.; Rodríguez-Mansilla, J. Cognitive Stimulation in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7225. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207225

Jiménez-Palomares M, Montero-Barrero O, Garrido-Ardila EM, Gibello-Rufo A, González-Sánchez B, Rodríguez-Mansilla J. Cognitive Stimulation in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7225. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207225

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Palomares, María, Olga Montero-Barrero, Elisa María Garrido-Ardila, Alicia Gibello-Rufo, Blanca González-Sánchez, and Juan Rodríguez-Mansilla. 2025. "Cognitive Stimulation in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7225. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207225

APA StyleJiménez-Palomares, M., Montero-Barrero, O., Garrido-Ardila, E. M., Gibello-Rufo, A., González-Sánchez, B., & Rodríguez-Mansilla, J. (2025). Cognitive Stimulation in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7225. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207225