Narcolepsy Beyond Medication: A Scoping Review of Psychological and Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Narcolepsy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

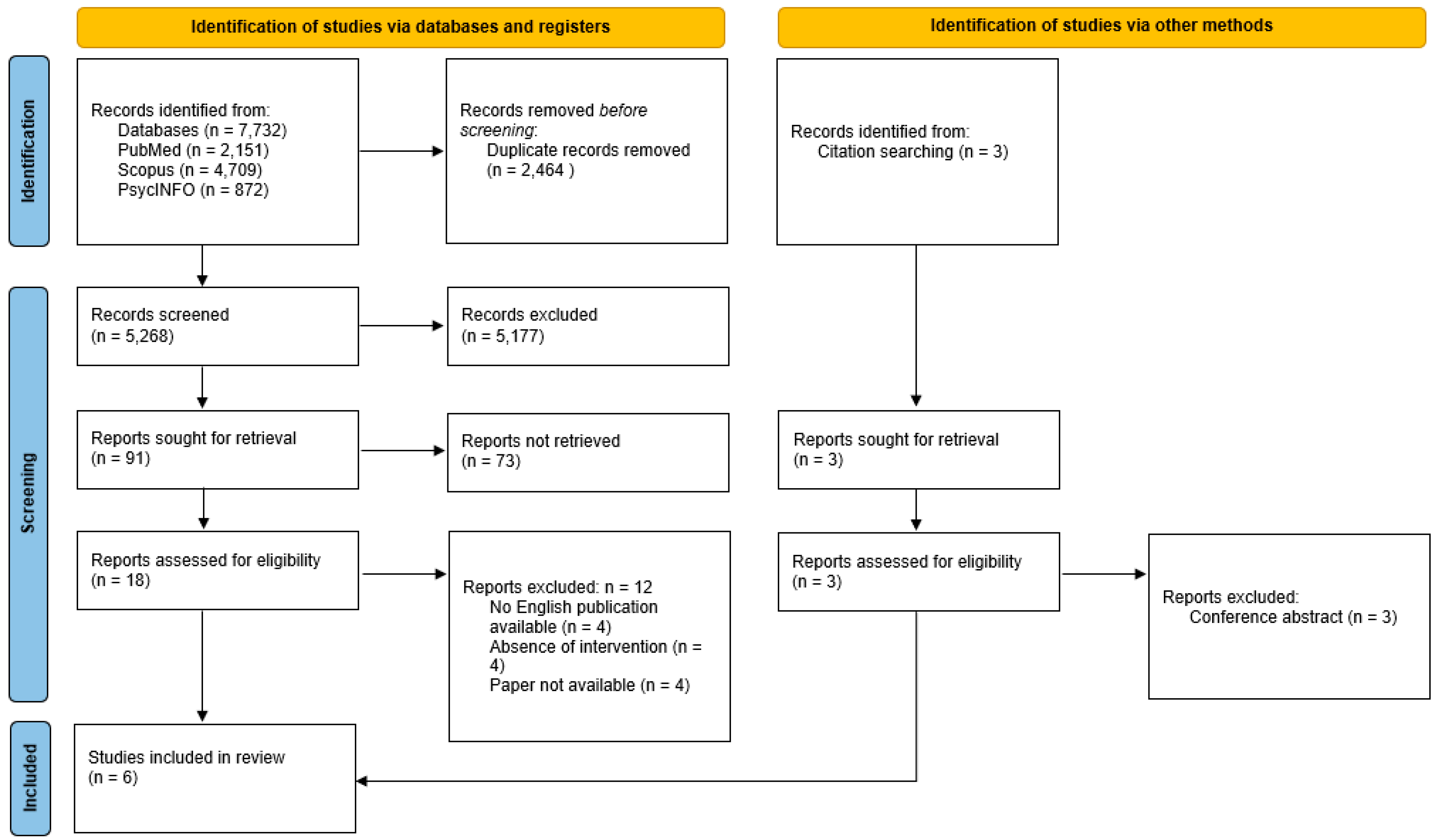

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Quality

3.3. Description of Participants

3.4. Study Characteristics

3.5. Description of Interventions

3.5.1. Intervention Group

3.5.2. Control Group

3.6. Effects of the Intervention Across Time Points

3.6.1. Primary Outcomes

3.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Napping on Daytime Sleepiness

4.2. The Effect of Psychological Intervention on Daytime Sleepiness

4.3. The Effect of Napping Intervention on Symptom Severity

4.4. Sleep Paralysis

4.5. Other Sleep-Related Outcomes

4.6. Psychological Well-Being

4.7. Research Gap and Future Study Recommendations

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Arnulf, I.; Mignot, E. Narcolepsy with Cataplexy. Lancet 2007, 369, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mignot, E.; Lammers, G.J.; Ripley, B.; Okun, M.; Nevsimalova, S.; Overeem, S.; Vankova, J.; Black, J.; Harsh, J.; Bassetti, C.; et al. The Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid Hypocretin Measurement in the Diagnosis of Narcolepsy and Other Hypersomnias. Arch. Neurol. 2002, 59, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, S.; Ripley, B.; Overeem, S.; Nevsimalova, S.; Lammers, G.J.; Vankova, J.; Okun, M.; Rogers, W.; Brooks, S.; Mignot, E. Low Cerebrospinal Fluid Hypocretin (Orexin) and Altered Energy Homeostasis in Human Narcolepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2001, 50, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazzi, G.; Clawges, H.M.; Owens, J.A. Clinical Characteristics and Burden of Illness in Pediatric Patients with Narcolepsy. Pediatr. Neurol. 2018, 85, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Kallweit, U.; Vignatelli, L.; Plazzi, G.; Lecendreux, M.; Baldin, E.; Dolenc-Groselj, L.; Jennum, P.; Khatami, R.; Manconi, M.; et al. European Guideline and Expert Statements on the Management of Narcolepsy in Adults and Children. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazzi, G.; Zanalda, E.; Cricelli, C. Disturbi Del Sonno: Focus Sulla Narcolessia. Evid.-Based Psychiatr. Care 2021, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, N.; Nishino, S. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Narcolepsy. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2011, 13, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, D.R.; Quinnell, T.G. Unmet Needs of Patients with Narcolepsy: Perspectives on Emerging Treatment Options. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2015, 7, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, V.; Venezia, N.; Iriti, A.; Quattrocchi, S.; Zenesini, C.; Biscarini, F.; Atti, A.R.; Menchetti, M.; Franceschini, C.; Varallo, G.; et al. Eating Disorders in Narcolepsy Type 1: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Italian Study. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e14150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varallo, G.; Musetti, A.; D’anselmo, A.; Gori, A.; Giusti, E.M.; Pizza, F.; Castelnuovo, G.; Plazzi, G.; Franceschini, C. Exploring Addictive Online Behaviors in Patients with Narcolepsy Type 1. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varallo, G.; Franceschini, C.; Rapelli, G.; Zenesini, C.; Baldini, V.; Baccari, F.; Antelmi, E.; Pizza, F.; Vignatelli, L.; Biscarini, F.; et al. Navigating Narcolepsy: Exploring Coping Strategies and Their Association with Quality of Life in Patients with Narcolepsy Type 1. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varallo, G.; Pingani, L.; Musetti, A.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Pizza, F.; Castelnuovo, G.; Plazzi, G.; Franceschini, C. Portrayals of Narcolepsy from 1980 to 2020: A Descriptive Analysis of Stigmatizing Content in Newspaper Articles. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodel, R.; Peter, H.; Spottke, A.; Noelker, C.; Althaus, A.; Siebert, U.; Walbert, T.; Kesper, K.; Becker, H.F.; Mayer, G. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2007, 8, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennum, P.; Ibsen, R.; Petersen, E.R.; Knudsen, S.; Kjellberg, J. Health, Social, and Economic Consequences of Narcolepsy: A Controlled National Study Evaluating the Societal Effect on Patients and Their Partners. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sanford, L.D.; Zong, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, L.; Li, T.; Ren, R.; Zhou, J.; Han, F.; Tang, X. Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Narcolepsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2021, 31, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Paquereau, J.; Bastuji, H.; Drouot, X.; Weil, J.S.; Viot-Blanc, V. Psychological Health in Central Hypersomnias: The French Harmony Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2009, 80, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuyn, H.A.; Lappenschaar, M.A.; Furer, J.W.; Hodiamont, P.P.; Rijnders, C.A.; Renier, W.O.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Overeem, S. Anxiety and Mood Disorders in Narcolepsy: A Case-Control Study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, E.C.; Flygare, J.; Paruthi, S.; Sharkey, K.M. Living with Narcolepsy: Current Management Strategies, Future Prospects, and Overlooked Real-Life Concerns. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2020, 12, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, C.; Pizza, F.; Cavalli, F.; Plazzi, G. A Practical Guide to the Pharmacological and Behavioral Therapy of Narcolepsy. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthaler, T.; Kapur, V.; Brown, T.; Swick, T.; Alessi, C.; Aurora, R.; Boehlecke, B.; Chesson, A.J.; Friedman, L.; Maganti, R.; et al. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Narcolepsy and Other Hypersomnias of Central Origin. Sleep 2007, 30, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiard, M.; Bassetti, C.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Dolenc-Groselj, L.; Lammers, G.J.; Mayer, G.; Pollmächer, T.; Reading, P.; Sonka, K. EFNS Guidelines on Management of Narcolepsy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006, 13, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalal, B.; Moruzzi, L.; Zangrandi, A.; Filardi, M.; Franceschini, C.; Pizza, F.; Plazzi, G. Meditation-Relaxation (MR Therapy) for Sleep Paralysis: A Pilot Study in Patients with Narcolepsy. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullington, J.; Broughton, R. Scheduled Naps in the Management of Daytime Sleepiness in Narcolepsy-Cataplexy. Sleep 1993, 16, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, J.M.; Zee, P.C.; Schuiling, M.D.; Hakenjos, A.J.; Victorson, D.E.; Fox, R.S.; Dawson, S.C.; Rogers, A.E.; Ong, J.C. Development of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Narcolepsy: A Feasibility Study. Sleep 2024, 47, zsae137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.C.; Dawson, S.C.; Mundt, J.M.; Moore, C. Developing a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Hypersomnia Using Telehealth: A Feasibility Study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 2047–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.E.; Aldrich, M.S.; Lin, X. A Comparison of Three Different Sleep Schedules for Reducing Daytime Sleepiness in Narcolepsy. Sleep 2001, 24, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.E.; Aldrich, M.S. The Effect of Regularly Scheduled Naps on Sleep Attacks and Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Narcolepsy. Nurs. Res. 1993, 42, 111–117. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/24/4/385/2750009 (accessed on 2 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cheyne, J.A.; Pennycook, G. Sleep Paralysis Postepisode Distress: Modeling Potential Effects of Episode Characteristics, General Psychological Distress, Beliefs, and Cognitive Style. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 1, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barateau, L.; Lopez, R.; Chenini, S.; Pesenti, C.; Rassu, A.L.; Jaussent, I.; Dauvilliers, Y. Depression and Suicidal Thoughts in Untreated and Treated Narcolepsy: Systematic Analysis. Neurology 2020, 95, E2755–E2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, K.; Wicks, M.N.; Martin, J.C. Chronic Disease Self-Management Improved with Enhanced Self-Efficacy. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2004, 13, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattivelli, R.; Guerrini Usubini, A.; Manzoni, G.M.; Vailati Riboni, F.; Pietrabissa, G.; Musetti, A.; Franceschini, C.; Varallo, G.; Spatola, C.; Giusti, E.; et al. ACTonFood. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy-Based Group Treatment Compared to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Based Group Treatment for Weight Loss Maintenance: An Individually Randomized Group Treatment Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, H.S.; Taylor, S.R. Exercise and Sleep. Sleep Med. Rev. 2000, 4, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraikat, F.M.; Wood, R.A.; Barragán, R.; St-Onge, M.-P. Sleep and Diet: Mounting Evidence of a Cyclical Relationship. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Preliminaries (/5) | Introduction (/5) | Design (/5) | Sampling (/5) | Data Collection (/5) | Ethical Matters (/5) | Results (/5) | Discussion (/5) | Total (/40) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 28 (70%) |

| [26] | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | NA | 4/5 | 3/5 | 26/40 (65%) |

| [27] | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 36/40 (90%) |

| [28] | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 30/40 (75%) |

| [29] | 4/5 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 30/40 (75%) |

| [30] | 3/5 | 4/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 3/5 | NA | 3/5 | 3/5 | 20/40 (50%) |

| Ref. | Country | Design | Study Aim | Sample Size (n, IG:CG) | Sex (n, Male: Female) | Age (yrs): Mean; SD; Range | Types of Diagnosis | Control Group (Type) | Follow-Up Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Italy | Non-randomized control trial | To evaluate the efficacy of a meditation–relaxation intervention for SP in a group of patients with NT1 and NT2 | 10, 6:4 | NR:NR | 27.8; 12.2; NR | NT1 and NT2 + occurrence of SP at least four times during the last month | Deep breathing | 8 weeks |

| [26] | USA | Pretest–posttest design | To reduce excessive daytime sleepiness | 8 | 4:4 | 42.75; NR; 19–55 | NT1 | No CG | 8 days |

| [27] | USA | Longitudinal study | To examine the acceptability and feasibility of a mindfulness-based intervention for narcolepsy, with three different program lengths, and the effect of the intervention on levels of mindfulness, self-compassion, psychosocial and neurocognitive functioning, and symptomatology | 60 | 53:5 2: non-binary | 35.6;12.2; NR | NT1 and NT2 | No control group | 4, 8, and 12 weeks |

| [28] | USA | Non-randomized trial | To determine the feasibility and acceptability of a novel cognitive behavioral therapy for depression daytime sleepiness, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life of people with CDH | 35, 19 (IG1 individual): 16 (IG2 group) | 3:32 | 32.0; 12.9; NR | CDH | No CG | 6 weeks |

| [29] | USA | RCT | To determine whether an intervention combining scheduled sleep periods with stimulant medications was more effective in improving daytime sleepiness and severity of symptoms of patients with NT1 than the administration of stimulant medications alone | 29, 9: 10 (CG1): 10 (CG2) | 12:17 | 43.7; 13.9; 18–64 | NT1 | CG1 (two regularly scheduled 15 min naps per day); CG2 (regular sleep schedule for arising and retiring each day) | 2 weeks |

| [30] | NR | Pretest–posttest design | To determine whether a specified number of scheduled naps would improve daytime alertness, reduce the severity of narcolepsy symptoms, and improve the quality of life of patients with NT1 | 16 | 7:9 | 46.8; 12.6; 21–65 | NT1 | No CG | 4 weeks |

| Ref. | Primary Outcomes (Measure) | Secondary Outcomes (Measure) | Drop-Out N (%) | Results (Primary Outcomes) | Results (Secondary Outcomes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | SP frequency in terms of the number of days; SP occurrence and the total number of SP episodes, duration of SP in the last month (SP-EPQ) | NR | NR | Significant reduction in the number of days in which SP occurred (t5 = 4.68, p = 0.002, one-tailed, d = 1.91) (IG: Δ = −5.50; CG: Δ = +0.25), as well as a 54% reduction in the total number of SP episodes (t5 = 3.86, p = 0.006, one-tailed, d = 1.57) (IG: Δ = −7.50; CG: Δ = +0.75). The reduction in episode duration was not significant (IG: Δ = −160.95; CG: Δ = +121.09). | NR |

| [26] | Excessive daytime sleepiness: descending subtraction test, a grammatical transformation or logical reasoning test, four-choice reaction time test, grip strength test, a measure of oral temperature, a number of additional subjective evaluation questions | NR | NR | The frequency of unscheduled sleep episodes did not exhibit a statistically significant difference across the various conditions; however, there was a marked reduction in the IG2 group compared to the IG1 group, approaching significance (p = 0.08). The number of unscheduled minutes of sleep recorded in the IG2 condition was less than that observed in the other conditions, approaching statistical significance when compared to IG1 (p = 0.07). Sleep efficiency was higher in the IG3 compared with the IG2 (IG3 > IG2 > IG1, p < 0.05). The percent of the scheduled bed period spent in active wakefulness was higher in IG2 compared to IG3 (IG2 > IG1 > IG3, p < 0.05). Reaction time significantly improved in IG2 compared to IG1 (IG2 > IG3 > IG1, p < 0.05). The grammatical transformation test results were lower in the napping condition than in the no-nap condition. | NR |

| [27] | Attendance, meditation practice, and data completeness | Mindfulness (FFMQ), self-compassion (SCS), mood (PROMIS), sleep (PROMIS, ESS, HSI, FOSQ) psychosocial functioning (PROMIS), and cognition (TMT, RBANS, SCWT, COWAT) | NR | Participants met the benchmarks for attendance, meditation, and data completeness in 71.7%, 61.7%, and 78.3% of cases, respectively. Moreover, a higher proportion of participants in the brief and extended intervention groups met these criteria compared to those in the standard group. | All intervention groups attained the minimal clinically important difference in mindfulness, self-compassion, emotional self-efficacy, positive psychosocial outcomes, overall mental health, and fatigue. Furthermore, both the standard and extended intervention groups achieved the minimal clinically important difference for reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms. The extended intervention group also exhibited clinically meaningful improvements in social and cognitive functioning, daytime sleepiness, hypersomnolence symptoms, and hypersomnia-related functional impairment. |

| [28] | Depression (PHQ), daytime sleepiness (ESS), psychosocial functioning (PROMIS) | Quality of life (FOSQ); sleep inertia (SIQ), sleep quality (RSQ) | 8.5% | A total of 40% of the sample experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms from baseline to posttreatment (p < 0.0001, d = 0.80), and 50% of participants who underwent group-based CBT-H (IG2) reported symptom reduction. Effect size analyses from baseline to post-treatment suggested that IG2 demonstrated greater efficacy than the individual IG. The total sample increased in PROMIS self-efficacy from T0 to T1, with no significant differences between groups (p = 0.0009, d = 0.62). ESS decreased significantly at follow-up in the total sample, with no differences between groups (p = 0.04, d = −0.35). | Secondary outcomes did not change across follow-up points. |

| [29] | Excessive daytime sleepiness (24 h ambulatory polysomnographic monitoring) and severity of narcolepsy symptoms (NSSQ) | NR | NR | CG1 (scheduled naps) and CG2 (regular bedtimes) had almost identical reductions in daytime sleep (0.06 min; SE= 9.75 min), and IG (combination therapy) had much more reduction in daytime sleep duration than CGs (16.5 min; SE = 10.8 min). No differences were found between IG and CGs in NSSQ (p = 0.87). The effectiveness of scheduled sleep periods is strongly related to pre-treatment levels of daytime sleepiness. Participants with severe daytime sleepiness reported more benefit from the inclusion of scheduled sleep periods. On the contrary, participants with moderate or mild sleepiness did not (p = 0.028). | NR |

| [30] | Daytime alertness (as measured with the MWT), severity of narcolepsy symptoms (evaluated with the NSSQ), sleep attacks + time/duration of any naps + (evaluated with sleep diaries) | NR | NR | Mean sleep latency on the MWT increased significantly at the 4-week follow-up (t0: 7.4 ± 6.0 min; t1: 10.0 ± 5.8 min; p < 0.05. Sleep attacks did not change (t0: 0.5 ± 0.6 sleep attacks per day; t1: 0.6 ± 0.6), nor did any other symptoms. | NR |

| Ref. | Setting | Provider (Background) | Duration of Intervention (Number of Sessions) | Clinical Approach | Intervention Approach | Format | Brief Description of the Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | At home | Experimenter (NR) | 8 weeks (NR) | Cognitive behavioral therapy | Psychoeducational + psycho-behavioral strategies | In-person or video call instruction + at-home implementation | Meditation and relaxation therapy is an intervention for sleep paralysis which includes the use of the following strategies during the sleep paralysis attack: step I: reappraisal of the meaning of the attack; step II: psychological and emotional distancing; step III: inward focused-attention meditation; step IV: muscle relaxation. |

| [26] | In a bed-and-breakfast establishment in a quiet rural setting | NR | 8 days (8) | Behavioral therapy | Behavioral | In-person instruction + at-home implementation | Following a two-day adaptation phase during which participants were allowed to sleep ad libitum, three experimental sleep protocols were implemented, each ensuring an equivalent total sleep duration within a 24 h period. In the first condition (IG1), sleep was consolidated into a single nocturnal episode with no daytime naps. The second condition (IG2) employed a long nap protocol, while the third condition (IG3) utilized a multiple short nap protocol. Both IG2 and IG3 involved a reduction in nocturnal sleep, which was supplemented by daytime sleep either through a single extended nap (IG2) or five evenly distributed short naps (IG3) during the remaining wakefulness period. |

| [27] | At home | Mindfulness Instructor | Brief Mindfulness-based intervention: 4 weeks (4) Standard mindfulness-based intervention: 8 weeks (8) Extended mindfulness-based intervention: 12 weeks (12) | Mindfulness | Psychoeducational– experiential | Online intervention | The intervention was based on the content and structure of mindfulness-based stress reduction. During each session, the instructor offered educational guidance, facilitated group discussions, and guided participants through mindfulness exercises such as body scan meditation, seated meditation, walking meditation, and yoga. |

| [28] | At home | 4 therapists (2 therapists were licensed clinical psychologists, 1 therapist was a postdoctoral fellow, and 1 therapist was a doctoral student in clinical psychology) | 6 weeks (6 sessions of 1 h each) | Cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia | Psychoeducational + psycho-behavioral strategies | Online intervention | CBT-H was designed as a modular treatment to address issues related to quality of life for both narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia. Each module consisted of a specific psychological and/or behavioral activities and homework assignments that were customized to provide flexibility in addressing disease-specific symptoms of people with NT1, NT2, and idiopathic hypersomnia. |

| [29] | At home | NR | 2 weeks (NR) | Behavioral therapy | Behavioral | In-person instruction + at-home implementation | Scheduled naps combined with regular bedtimes. |

| [30] | At home | Polysomnographic technologist | 4 weeks (NR) | Behavioral therapy | Behavioral | In-person instruction + at-home implementation | Three regularly scheduled naps. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varallo, G.; Musetti, A.; Filosa, M.; Rapelli, G.; Pizza, F.; Plazzi, G.; Franceschini, C. Narcolepsy Beyond Medication: A Scoping Review of Psychological and Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Narcolepsy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082608

Varallo G, Musetti A, Filosa M, Rapelli G, Pizza F, Plazzi G, Franceschini C. Narcolepsy Beyond Medication: A Scoping Review of Psychological and Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Narcolepsy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(8):2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082608

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarallo, Giorgia, Alessandro Musetti, Maria Filosa, Giada Rapelli, Fabio Pizza, Giuseppe Plazzi, and Christian Franceschini. 2025. "Narcolepsy Beyond Medication: A Scoping Review of Psychological and Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Narcolepsy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 8: 2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082608

APA StyleVarallo, G., Musetti, A., Filosa, M., Rapelli, G., Pizza, F., Plazzi, G., & Franceschini, C. (2025). Narcolepsy Beyond Medication: A Scoping Review of Psychological and Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Narcolepsy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(8), 2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082608