Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

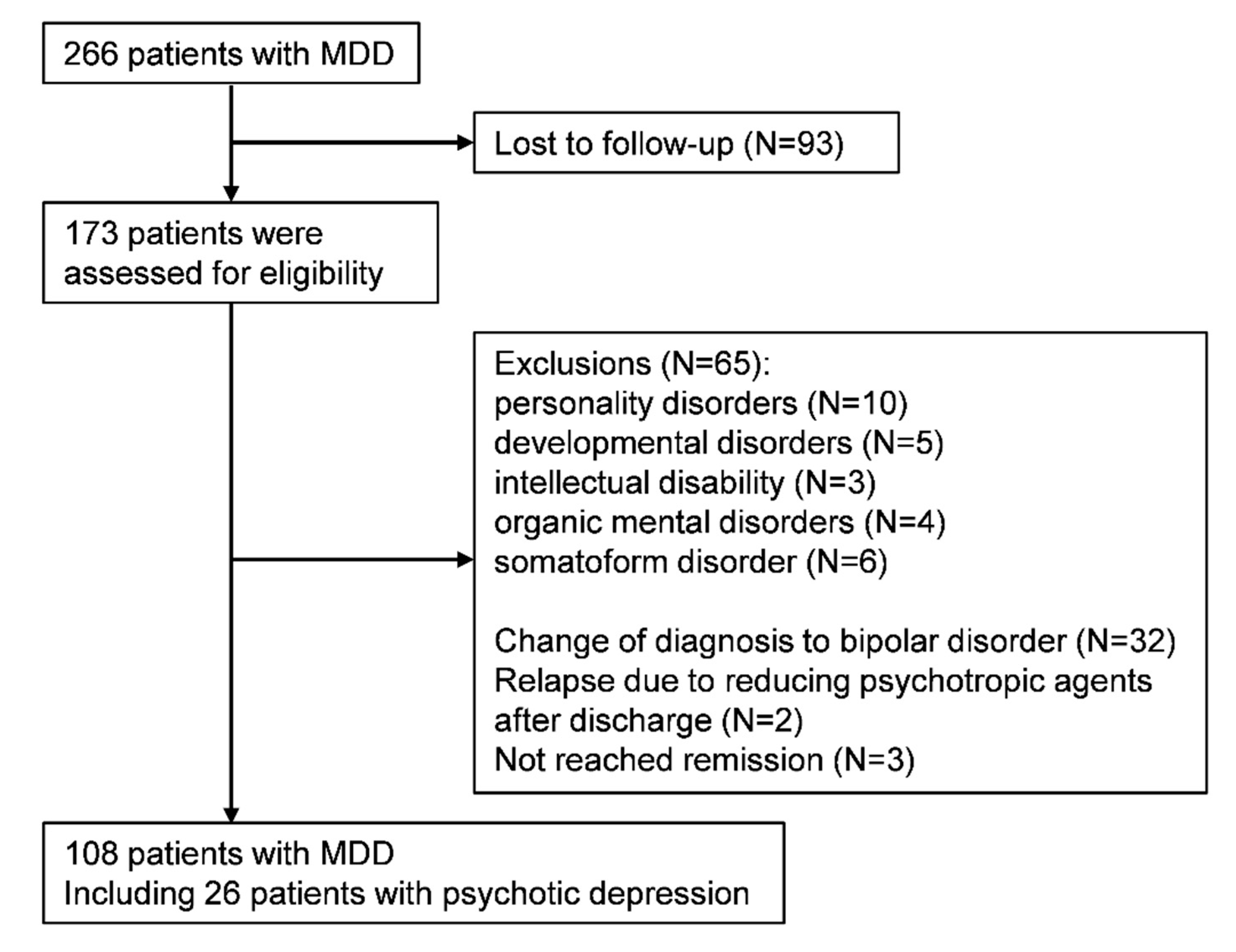

2.2. Study Cohort

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Benzodiazepine Score

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

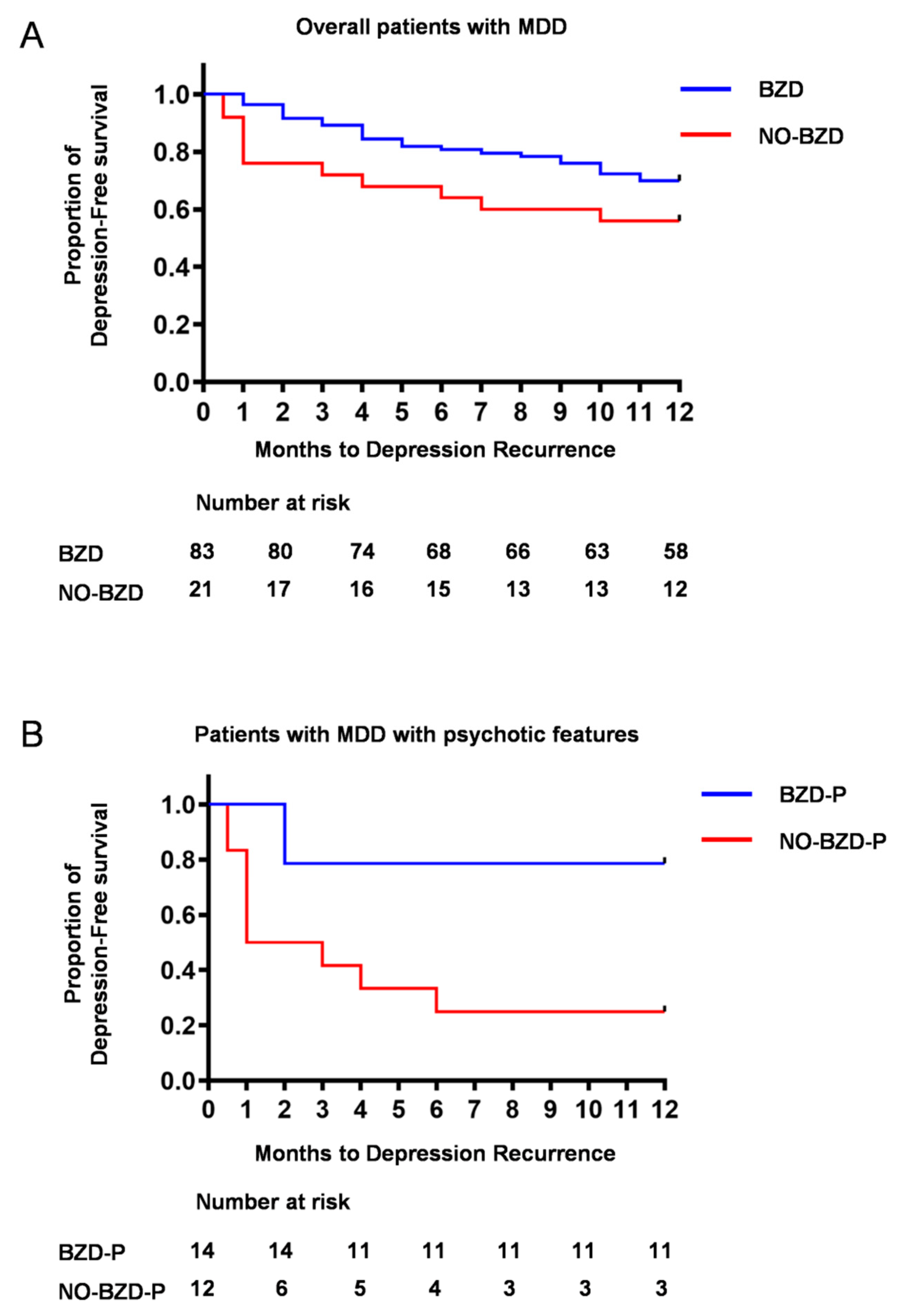

3.2. Time to Depression Relapse/Recurrence

3.3. Dose-Dependent Effect of Benzodiazepines on Time to Depression Relapse/Recurrence

3.4. Relapse/Recurrence in Psychotic Depression

3.5. A Case Report

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keller, M.B.; Trivedi, M.H.; Thase, M.E.; Shelton, R.C.; Kornstein, S.G.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Friedman, E.S.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Kocsis, J.H.; Dunner, D.L.; et al. The prevention of recurrent episodes of depression with venlafaxine for two years (prevent) study: Outcomes from the 2-year and combined maintenance phases. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Amsterdam, J.D.; Quitkin, F.M.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Fava, M.; Zajecka, J.; Beasley, C.M., Jr.; Michelson, D.; Roback, P.; Sundell, K. Optimal length of continuation therapy in depression: A prospective assessment during long-term fluoxetine treatment. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, K.; Lau, W.K.; Sim, J.; Sum, M.Y.; Baldessarini, R.J. Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lader, M. Benzodiazepines revisited--will we ever learn? Addiction 2011, 106, 2086–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, R.G.; Le Couteur, D.G. Benzodiazepines and risk of hip fractures in older people: A review of the evidence. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioti de Gage, S.; Begaud, B.; Bazin, F.; Verdoux, H.; Dartigues, J.F.; Peres, K.; Kurth, T.; Pariente, A. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: Prospective population based study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2012, 345, e6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Billioti de Gage, S.; Moride, Y.; Ducruet, T.; Kurth, T.; Verdoux, H.; Tournier, M.; Pariente, A.; Begaud, B. Benzodiazepine use and risk of alzheimer’s disease: Case-control study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2014, 349, g5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weich, S.; Pearce, H.L.; Croft, P.; Singh, S.; Crome, I.; Bashford, J.; Frisher, M. Effect of anxiolytic and hypnotic drug prescriptions on mortality hazards: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2014, 348, g1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. National institute for health and clinical excellence: Guidance. In Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition); British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK; Copyright (c) The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists: Leicester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Y.; Takeshima, N.; Hayasaka, Y.; Tajika, A.; Watanabe, N.; Streiner, D.; Furukawa, T.A. Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for adults with major depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, Cd001026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benasi, G.; Guidi, J.; Offidani, E.; Balon, R.; Rickels, K.; Fava, G.A. Benzodiazepines as a monotherapy in depressive disorders: A systematic review. Psychother. Psychosom. 2018, 87, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bushnell, G.A.; Sturmer, T.; Gaynes, B.N.; Pate, V.; Miller, M. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, united states, 2001–2014. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manthey, L.; Giltay, E.J.; van Veen, T.; Neven, A.K.; Zitman, F.G.; Penninx, B.W. Determinants of initiated and continued benzodiazepine use in the netherlands study of depression and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 31, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Inada, T.; Inagaki, A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Lam, R.W.; McIntyre, R.S.; Tourjman, S.V.; Bhat, V.; Blier, P.; Hasnain, M.; Jollant, F.; Levitt, A.J.; MacQueen, G.M.; et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (canmat) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2016, 61, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered connectivity in depression: Gaba and glutamate neurotransmitter deficits and reversal by novel treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, G.; van der Veen, J.W.; Tumonis, T.; Meyers, N.; Shen, J.; Drevets, W.C. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Price, R.B.; Shungu, D.C.; Mao, X.; Nestadt, P.; Kelly, C.; Collins, K.A.; Murrough, J.W.; Charney, D.S.; Mathew, S.J. Amino acid neurotransmitters assessed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy: Relationship to treatment resistance in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fee, C.; Banasr, M.; Sibille, E. Somatostatin-positive gamma-aminobutyric acid interneuron deficits in depression: Cortical microcircuit and therapeutic perspectives. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 82, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; Jefferson, S.J.; Hooper, A.; Yee, P.H.; Maguire, J.; Luscher, B. Disinhibition of somatostatin-positive gabaergic interneurons results in an anxiolytic and antidepressant-like brain state. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, F.; Fatouros-Bergman, H.; Goiny, M.; Malmqvist, A.; Piehl, F.; Cervenka, S.; Collste, K.; Victorsson, P.; Sellgren, C.M.; Flyckt, L.; et al. Csf gaba is reduced in first-episode psychosis and associates to symptom severity. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dold, M.; Bartova, L.; Kautzky, A.; Porcelli, S.; Montgomery, S.; Zohar, J.; Mendlewicz, J.; Souery, D.; Serretti, A.; Kasper, S. Psychotic features in patients with major depressive disorder: A report from the european group for the study of resistant depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fava, G.A.; Ruini, C.; Rafanelli, C.; Finos, L.; Conti, S.; Grandi, S. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1872–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balon, R.; Starcevic, V.; Silberman, E.; Cosci, F.; Dubovsky, S.; Fava, G.A.; Nardi, A.E.; Rickels, K.; Salzman, C.; Shader, R.I.; et al. The rise and fall and rise of benzodiazepines: A return of the stigmatized and repressed. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2020, 42, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Overall Patients with MDD (N = 108) | Patients with MDD with Psychotic Features (N = 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | BZD (N = 83: Patients Who Received BZDs) | NO-BZD (N = 25: Patients Who Did Not Received BZDs) | BZD-P (n = 14: Patients Who Received BZDs) | NO-BZD-P (n = 12: Patients Who Did Not Received BZDs) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Female sex | 57 (68.7%) | 17 (68.0%) | 11 (78.5%) | 10 (83.3%) |

| antidepressants | ||||

| SSRIs | 34 (41.0%) | 11 (44.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| SNRIs | 15 (18.1%) | 7 (28.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| mirtazapine | 36 (43.4%) | 7 (28.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| antipsychotics | 36 (43.4%) | 11 (44.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| olanzapine | 8 (9.6%) | 3 (12.0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| quetiapine | 19 (22.9%) | 7 (28.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 4 (33.3%) |

| mECT | 13 (15.7%) | 11 (44.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| 296.2x | 29 (34.9%) | 9 (36.0%) | ||

| 296.21/296.22 | 19 (22.9%) | 2 (8.0%) | ||

| 296.23 | 5 (6.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | ||

| 296.24 | 4 (4.8%) | 6 (24.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| 296.3x | 54 (65.1%) | 16 (64.0%) | ||

| 296.31/296.32 | 32 (38.6%) | 5 (20.0%) | ||

| 296.33 | 8 (9.6%) | 5 (20.0%) | ||

| 296.34 | 10 (12.0%) | 6 (24.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| age | 63.9 (13.2) | 62.5 (16.4) | 71.2 (9.79) | 72.7 (10.0) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Period from onset | 6.5 (2.0~13.8) | 4.0 (0.5~12.5) | 7.0 (3.0~14.0) | 3.0 (0.25~12.8) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| HAM-D | 23.5 (5.1) | 26.9 (7.28) | 33.1 (2.8) | 32.6 (2.7) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Length of hospitalization (months) | 2.0 (2–3) | 2.0 (1.5–3) | 3.0 (2–3) | 2.75 (2–3.5) |

| Parameter | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| benzodiazepines | 8.340 | 1.621–41.92 | 0.011 |

| SSRI | 0.313 | 0.028–3.424 | 0.341 |

| SNRI | 0.488 | 0.043–5.504 | 0.561 |

| mirtazapine | 5.784 | 0.680–49.26 | 0.108 |

| olanzapine | 1.125 | 0.244–5.189 | 0.880 |

| quetiapine | 3.552 | 0.614–20.57 | 0.157 |

| Patients with MDD with Psychotic Features (N = 26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Relapse/Recurrence (N = 13) | Without Relapse/Recurrence (N = 13) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | p-Value | |

| Female sex | 11 (84.6%) | 10 (76.9%) | >0.999 |

| antidepressants | |||

| SSRIs | 7 (53.9%) | 7 (53.9%) | >0.999 |

| SNRIs | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0.673 |

| mirtazapine | 2 (15.4%) | 8 (61.5%) | 0.0414 |

| antipsychotics | 8 (61.5%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.434 |

| olanzapine | 4 (30.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0957 |

| quetiapine | 3 (23.1%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.673 |

| mECT | 9 (69.2%) | 11 (75.6%) | 0.678 |

| diagnosis | |||

| 296.24 | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.4%) | 0.434 |

| 296.34 | 8 (61.4%) | 5 (38.5%) | 0.434 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| age | 75.2 (8.54) | 68.7 (10.1) | 0.0777 |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Period from onset | 2.0 (0.5~11.5) | 5.0 (1.5~14.0) | 0.340 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| HAM-D | 32.8 (2.66) | 32.8 (2.81) | 0.946 |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Duration of hospitalization (months) | 2.5 (2–3) | 3.0 (2–4) | 0.476 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shiwaku, H.; Fujita, M.; Takahashi, H. Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938

Shiwaku H, Fujita M, Takahashi H. Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(6):1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938

Chicago/Turabian StyleShiwaku, Hiroki, Masako Fujita, and Hidehiko Takahashi. 2020. "Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 6: 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938

APA StyleShiwaku, H., Fujita, M., & Takahashi, H. (2020). Benzodiazepines Reduce Relapse and Recurrence Rates in Patients with Psychotic Depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(6), 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061938