Know the Farmer That Feeds You: A Cross-Country Analysis of Spatial-Relational Proximities and the Attractiveness of Community Supported Agriculture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background on Proximity and Operationalization for CSA

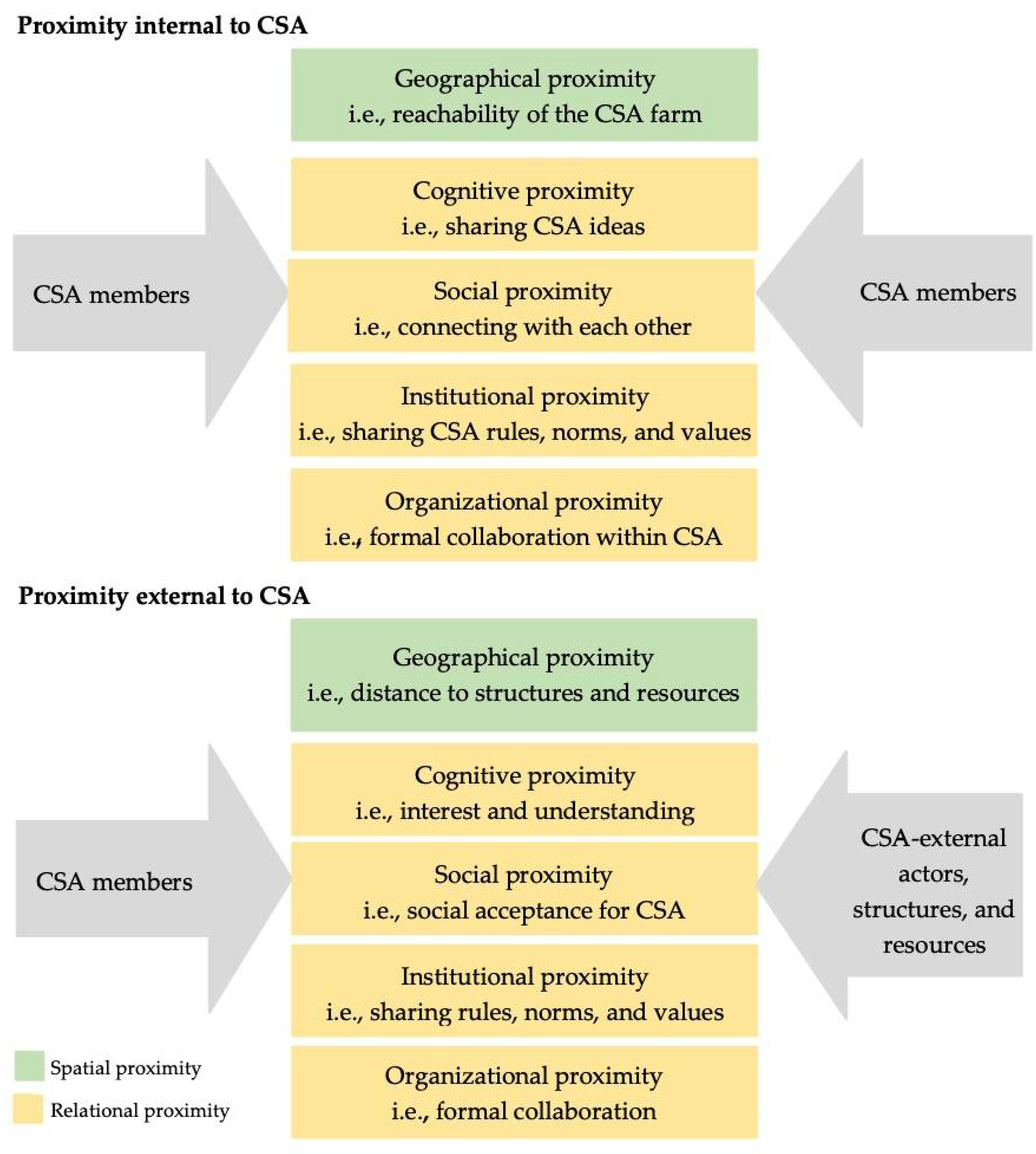

- Operationalization of cognitive proximity: The degree to which CSA members empathize with CSA ideas and thus share knowledge, competence, and expectations with respect to CSAs (CSA-internal), and, as CSA-external actors, the degree of interest in and understanding of the CSA model (CSA-external) [16,21,48].

- Operationalization of institutional proximity: The extent to which CSA rules, norms, and values are shared among CSA members (CSA-internal), and the similarities of the CSA institutions to external, prevailing food system institutions (i.e., production and market mechanisms of dominant food system actors) (CSA-external) [16,21,48,54].

- Geographical proximity: In general, CSAs seem to face a trade-off between the locational advantages of rural and urban areas. While CSAs target affordable access to biophysically suitable farmland that is predominantly located in rural areas, a CSA which has a location in or near a city with mainly urban CSA consumers represents a locational advantage (e.g., access to public transportation, infrastructure, networking opportunities) [21]. Thus, by being close to rural and urban areas, a CSA could stimulate a mutual understanding (i.e., cognitive proximity) between people in rural and urban areas (see next point) [30].

- Cognitive proximity: CSA members in Austria share knowledge, competence, and expectations of CSA ideas (e.g., pricing based on self-assessment) with each other, and therefore predominantly connect with individuals already connected to the CSA community (i.e., members of other CSA initiatives) [21]. CSA members’ empathy for CSA ideas promotes their endorsement of the CSA [57]. However, Austrian CSA members raised the concern that CSA ideas might be too difficult to understand for actors outside the CSA [21]. With the expansion of mainstream organic food marketing channels in Japan, the interest in CSAs among CSA-external actors is decreasing [58,59]. Thus, in terms of cognitive proximity, Japanese teikei might lack the ability to adapt to the expectations of today’s consumers [21]. In contrast, the growing demand for locally and organically produced food and a trend toward urban gardening in Norway might explain the growing interest of Norwegians in CSA and the rapid growth of CSAs in Norway [30,60,61,62].

- Social proximity: Personal contact with food system actors can increase trust or distrust in the system [63]. CSAs aim to create social proximity among their members by connecting them through network relationships, organizing meetings and events, and participatory decision making [21,30,57,60]. CSA members in Austria highlighted that trust-building activities among CSA members and with society are important for the CSA. Though they have built strong connections with other local CSA actors, relations with other (dominant) food system actors are rare, as stated by CSA members [21]. In Japan, building trusting relationships with actors outside their (teikei) community might be even more challenging due to a more collectivist pattern [64]. While trust within established and stable relationships (such as the teikei community) might be higher than in individualistic societies (i.e., Norway and Austria), it has been observed that Japanese tend to distrust actors outside these relationships [65].

- Institutional proximity: Several studies indicate that Austrian, Japanese, and Norwegian CSA members try to avoid institutionalizing the CSA but rather aim to disrupt conventional food provision practices, rules, norms, and values [21,35,59,66]. They aim to contrast the mainstream and seek an alternative form of food provision [67,68], characterized by typical CSA features (e.g., small-scale operation, short value chains, transparent food provision, social and ecological sustainability) [18,25,60]. Austrian and Norwegian CSAs emerged in response to the conventionalization of the organic food market (i.e., a process in which the organic food market increasingly takes on the characteristics/institutions of mainstream industrial agriculture), and thus CSA members tend to criticize the dominant structures of the food system [21,60,69,70]. In contrast, CSAs emerged in Japan before the Japanese organic food market became conventional, in response to the negative effects of chemically intensive and mechanized agriculture. However, the expansion and institutionalization (i.e., the introduction of a certification system and other government policies to adapt to the dominant structures of the conventional food system) of the organic market since the 1980s, as well as the introduction of a certification system for organic food, were largely responsible for the decline of CSAs in Japan [59].

- Organizational proximity: Due to the shared organizational arrangement, organizational proximity among members of the original teikei type (i.e., OF–OC teikei scheme) and European CSA organizations is high. However, formal collaboration between CSAs and other (dominant) food system actors seems to be less relevant for Austrian and Japanese CSA members [21,59]. In contrast, Norwegian CSAs receive financial and technical support as well as advisory services. The association Organic Norway, the Agricultural Extension Service, the Norwegian Agriculture Agency, and several county governors have been particularly supportive of CSAs, promoting them, and playing an important role in the development of CSAs in Norway [60,71,72]. Although closer links to non-CSA actors, such as government and public institutions, could generate additional resources for CSAs, they may also lead to a loss of independence [73].

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Site Selection

3.2. Setting up the Quantitative Analysis

3.3. Creating Proximity Variables

3.4. Interrelating Proximity to CSA Attractiveness

4. Results

- Principal component 1 groups CSA-internal social and cognitive proximities among CSA members. We labelled this factor social–cognitive proximity among CSA members.

- Principal component 2 includes variables describing CSA farm’s geographic proximity to CSA members and land (hence the name of this component). The variables illustrate the location conflict between the proximity to CSA members, mainly located in the city, and suitable land for cultivation by the CSA farm.

- Principal component 3 also contains geographic variables that ask about the CSA farm’s geographic proximity to external structures and resources (i.e., the name of this component), such as infrastructures and nearby services.

- Principal component 4 captures the CSA-external social and cognitive relations between the CSA members and CSA-external actors. We have referred to principal component 4 as CSA-external social–cognitive proximity.

- Principal component 5 contains variables on CSA members’ institutional proximity. Therefore, we termed principal component 5 institutional proximity among CSA members.

4.1. Interrelating Proximity to CSA Attractiveness

4.2. Descriptive Analysis of Country-Specific Results on Institutional and Organizational Proximity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ermann, U.; Langthaler, E.; Penker, M.; Schermer, M. Agro-Food Studies: Eine Einführung; UTB Böhlau Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2018; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Krausmann, F.; Langthaler, E. Food regimes and their trade links: A socio-ecological perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.C. Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. J. Rural. Stud. 2000, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penker, M. Mapping and measuring the ecological embeddedness of food supply chains. Geoforum 2006, 37, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weckenbrock, P.; Volz, P.; Parot, J.; Cressot, N. Introduction to Community Supported Agriculture in Europe. In Overview of Community Supported Agriculture in Europe; European CSA Research Group: Aubagne, France, 2016; pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jossart-Marcelli, P.; Bosco, F.J. Alternative food projects, localization and neoliberal urban development. Métropoles 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.J. Working the fields: The organization of labor in community supported agriculture. Organization 2020, 27, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Bartolini, F. Local agri-food systems in a global world: Market, social and environmental challenges. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2013, 40, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; Gibbon, D.; Dedieu, B. Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schermer, M. From ‘‘Food from Nowhere’’ to ‘‘Food from Here:’’ Changing producer—Consumer relations in Austria. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPuis, E.M.; Goodman, D. Should we go ‘‘home’’ to eat? Towards a reflexive politics of localism. J. Rural. Stud. 2005, 21, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milestad, R.; Westberg, L.; Geber, U.; Björklund, J. Enhancing adaptive capacity in food systems: Learning at farmers’ markets in Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kneafsy, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Bos, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. 2013. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2016)586650 (accessed on 18 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.C.H.; Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Making reconnections in agro-food geography: Alternative systems of food provision. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, C.; Kebir, L. Shortening food supply chains: A means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of Paris. Food Policy 2013, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, C.N. Globally useful conceptions of alternative food networks in the developing south: The case of Johannesburg’s urban food supply system. In Alternative Food Geographies: Representation and Practice; Maye, D., Holloway, L., Kneafsey, M., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2007; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sitaker, M.; McGuirt, J.T.; Wang, W.; Kolodinsky, J.; Seguin, R.A. Spatial considerations for implementing two direct-to-consumer food models in two states. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Struś, M.; Kalisik-Medelska, M.; Nadolny, M.; Kachniarz, M.; Raftowicz, M. Community-supported agriculture as a perspective model for the development of small agricultural holding in the region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gugerell, C.; Penker, M. Change Agents’ Perspectives on Spatial–Relational Proximities and Urban Food Niches. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubois, A. Translocal practices and proximities in short quality food chains at the periphery: The case of North Swedish farmers. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 236, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edelmann, H.; Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F.; Penker, M. Analytic Framework to Determine Proximity in Relationship Coffee Models. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 60, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kebir, L.; Torre, A. Geographical proximity and new short supply food chains. In Creative Industries and Innovation in Europe, Concepts, Measures, and Comparative Case Studies; Lazzeretti, L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Venuti, F.; Foscolo, E. How to avoid the tragedy of alternative food networks (AFNs)? The impact of social capital and transparency on AFN performance. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.; O’Sullivan, L.; Beckett, J.; Hiner, C.C. Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in and around California’s Central Valley: Farm and Farmer Characteristics, Farm-Member Relationships, Economic Viability and Emerging Issues; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bougheraraa, D.; Grolleaub, G.; Mzoughic, N. Buy local, pollute less: What drives households to join a community supported farm? Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W. Motivations for participating in community-supported agriculture and their relationship with community attachment and social capital. J. Rural. Soc. Sci. 2008, 23, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, R.; Holloway, L.; Venn, L.; Dowler, L.; Hein, J.R.; Kneafsey, M.; Tuomainen, H. Common ground? Motivations for participation in a community-supported agriculture scheme. Local Environ. 2008, 13, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvitsand, C. Organic Spearhead—The Role of Community Supported Agriculture in Enhancing Bio Economy, and Increased Knowledge about and Consumption of Organic Food; Title Translated from Norwegian; Telemark Research Institute: Bø, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, D.; Lohr, L. The Dangers of Space Turnips and Blind Dates: Bridging the Gap Between CSA Shareholders’ Expectations and Reality; CSA Farm Network: Stillwater, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cone, C.; Myhre, A. Community-supported Agriculture: A Sustainable Alternative to Industrial Agriculture? Hum. Organ. 2000, 59, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christensen, L.O.; Munden-Dixon, K. The (un)making of ‘‘CSA people’’: Member retention and the customization paradox in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in California. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witzling, L.; Shaw, B.R.; Strader, C.; Sedlak, C.; Jones, E. The role of community: CSA member retention. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2289–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitari, C.; Whittingham, E. Tackling Conventional Agriculture: The Institutionalization of Community Supported Agriculture’s (CSA) Principles. In Proceedings of the Research & Degrowth Conference, Malmö, Sweden, 21–25 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Balázs, B.; Pataki, G.; Lazányi, O. Prospects for the future: Community supported agriculture in Hungary. Futures 2016, 83, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nost, E. Scaling-up local foods: Commodity practice in community supported agriculture (CSA). J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christiensen, L.; Van Soelen Kim, J.; Lobo, R. Eroding the Community in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): Competition’s Effects in Alternative Food Networks in California. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christiensen, L.; Fake, C.; Munden-Dixon, K.; Simpson, N.; Surls, R.; Van Soelen Kim, J. What difference does income make for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) members in California? Comparing lower-income and higher-income households. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galt, R.E.; Bradley, K.; Christiensen, L.; Munden-Dixon, K. Exploring member data for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in California: Comparisons of former and current CSA members. Data Brief 2018, 21, 2082–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, J.; Woods, T. Understanding shareholder satisfaction and retention in CSA incentive programs. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2020, 51, 16–40. [Google Scholar]

- Darnhofer, I. Farming from a Process-Relational Perspective: Making Openings for Change Visible. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vroom, V.H. Organizational choice: A study of pre- and post-decision processes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1966, 1, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Information integration theory applied to expected job attractiveness and satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1973, 60, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belllet, M.; Colletis, G.; Lung, Y. Économie des proximités. Rev. D’économie Régionale Urbaine 1993, 3, 357–606. [Google Scholar]

- Rallet, A.; Torre, A. Is geographical proximity necessary in the innovation networks in the era of global economy? GeoJournal 1999, 49, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodysson, J.; Jonsson, O. Knowledge collaboration and proximity: The spatial organization of Biotech innovation projects. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2007, 14, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Raven, T.; Verbong, G. Local niche experimentation in energy transitions: A theoretical and empirical exploration of proximity advantages and disadvantages. Technol. Soc. 2010, 32, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holloway, L.; Cox, R.; Venn, L.; Kneafsey, M.; Dowler, E.; Tuomainen, H. Managing sustainable farmed landscape through ‘alternative’ food networks: A case study from Italy. Geogr. J. 2006, 172, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.; Buck, D. Doing community supported agriculture: Tactile space, affect and effects of membership. Geoforum 2012, 43, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Hingley, M.; Canavari, M.; Bregoli, I. Sustainability in Alternative Food Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossi, A. Beyond Food Provisioning: The Transformative Potential of Grassroots Innovation around Food. Agriculture 2017, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker, G. Social innovation in local food in Japan: Choku-bai-jo markets and Teikei cooperative practices. In Real Estate & Planning Working Papers; University of Reading: Reading, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edquist, C.; Johnson, B. Institutions and organizations in systems of innovation. In Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions, and Organizations; Edquist, C., Ed.; Pinter: London, UK, 1997; pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Breschi, S.; Lissoni, F. Mobility and Social Networks: Localised Knowledge Spillovers Revisited; CESPRI Working Paper No. 142; University Bocconi: Milano, Italy, 2003; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/cri/cespri/wp142.html (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Broekel, T.; Boschma, R. Knowledge networks in the Dutch aviation industry: The proximity paradox. J. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 12, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoggia, A.; Perazzolo, C.; Kocsis, P.; Del Prete, M. Community supported agriculture farmers’ perceptions of management benefits and drawbacks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatano, J. The organic agriculture movement (teikei) and factors leading to its decline in Japan. Rural Food Econ. 2008, 54, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh, K. The alternative food movement in Japan: Challenges, limits, and resilience of the teikei system. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvitsand, C. Community supported agriculture (CSA) as a transformational act—Distinct values and multiple motivations among farmers and consumers. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rømo Grande, E. Eating is an Agricultural Act: Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in Norway. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rømo Grande, E. Norway. In Overview of Community Supported Agriculture in Europe; European CSA Research Group: Aubagne, France, 2016; pp. 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Coff, C.; Korthals, M.; Barling, D. Ethical traceability and informed food choice. In Ethical Traceability and Communicating Food; The International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics; Coff, C., Barling, D., Korthals, M., Nielsen, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrin, D.L.; Gillespie, N. Trust differences across national-societal cultures: Much to do, or much ado about nothing? In Organizational Trust: A Cultural Perspective; Saunders, M.N., Skinner, D., Dietz, G., Gillespie, N., Lewicki, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 42–86. [Google Scholar]

- Storstad, O. The impact of consumer trust in the Norwegian food market. In Food, Nature and Society; Rural Life in Late, Modernity; Blanc, M., Tovey, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2001; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlmacher, E. Comparing Community Supported Agriculture in Vienna and Vancouver. Master’s Thesis, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Plank, C.; Hafner, R.; Stotten, R. Analyzing values-based modes of production and consumption: Community-supported agriculture in the Austrian Third Food Regime. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 2020, 45, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freyer, B.; Bingen, J. Re-Thinking Organic Food and Farming in a Changing World; The International Library of Environmental Agricultural and Food Ethics 22; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann, J. Regulating meaning, appropriating nature: The codification of California organic agriculture. Antipode 1998, 30, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devik, A. Håndbok for å Starte Andelslandbruk; Oikos–Økologisk Norge: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Organic Norway. Community Supported Agriculture in Norway (Translated). 2020. Available online: https://www.andelslandbruk.no/english-1/english (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Poças Ribeiro, A.; Harmsen, R.; Feola, G.; Rosales Carréon, J.; Worrell, E. Organising Alternative Food Networks (AFNs): Challenges and Facilitating Conditions of different AFN types in three EU countries. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braukmann, I. Potenzial und Grenzen von Community Supported Agriculture als Gegenhegemoniales Projekt. Master’s Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, S.R.; Akitsu, M. Steering sustainable food consumption in Japan: Trust, relationships, and the ties that bind. In Sustainable Consumption: Design, Innovation, and Practice; Genus, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Akitsu, M.; Aminaka, N. The development of farmer-consumer direct relationships in Japan: Focusing on the trade of organic produce. In Proceedings of the 4th Asian Rural Sociology Association (ARSA) International Conference, Legazpi City, Philippines, 7–10 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano, T. Economy of Organic Agriculture: TEIKEI Networks; Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha: Tokyo, Japan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano, T.; Karasaki, T. CSA, Agriculture for Sharing: Case Studies in US, Europe, and Japan; Soshinsya: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A.; Pabst, S.; Steigberger, E.; Wellmann, L. Austria. In Overview of Community Supported Agriculture in Europe; European CSA Research Group: Aubagne, France, 2016; pp. 12–15. Available online: http://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/416085/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Carifio, J.; Perla, R.J. Ten common misunderstandings, misconceptions, persistent myths and urban legends about Likert scales and Likert response formats and their antidotes. J. Soc. Sci. 2007, 3, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll, 15th ed.; Sage: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Manag. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.P.; Shaver, P.R.; Wrightsman, L.S. Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing, 2nd ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Country | (Peri-)urban Areas | CSA Members | Surveys (n = 209) | Organizational Similarities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Vienna | About 300 | 51 | Collective price negotiation; Year-round commitment of members; Participative decision-making processes |

| Graz | About 100 | 27 | ||

| Norway | Sandefjord | About 140 | 39 | |

| Porsgrunn | About 120 | 49 | ||

| Japan | Tokyo | About 40 | 25 | |

| Tsukuba | About 40 | 18 |

| Variable | Category | Austria (in %) | Japan (in %) | Norway (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 37.3 | 20.6 | 42.1 | |

| Gender | Female | 65.4 | 74.4 | 81.4 |

| Male | 34.6 | 25.6 | 17.4 | |

| Diverse | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | |

| Age | >24 years | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 25–44 years | 50.6 | 25.6 | 19.8 | |

| 45–64 years | 33.8 | 37.2 | 45.3 | |

| >65 years | 9.1 | 37.2 | 34.9 | |

| Work condition | Working full-time | 25.3 | 9.3 | 37.6 |

| Working part-time | 24.0 | 14.0 | 9.4 | |

| Being self-employed | 14.7 | 20.9 | 15.3 | |

| Being not employed (studying, retirement, parental leave, unemployment) | 28.0 | 41.9 | 36.5 | |

| Other | 8.0 | 14.0 | 1.2 |

| CSA-Internal Proximity | Operationalized Proximity Items as Presented in the Questionnaire | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social proximity among CSA members | Significance of connecting with the CSA community | 4.53 | 1.360 |

| Significance of direct connection with the CSA farmer | 4.83 | 1.227 | |

| Cognitive proximity among CSA members | Significance of empathy for CSA ideas of risk sharing and ensuring a secure income for local farmers | 5.23 | 1.145 |

| Institutional proximity among CSA members | Significance of traceability of food and transparency of production | 5.48 | 0.818 |

| Significance of becoming more independent from the regular agricultural market and its prices | 4.95 | 1.298 | |

| Significance to support the development of a new and more sustainable agricultural market | 5.63 | 0.758 | |

| Geographical proximity among CSA members | Extent of connection to CSA farm via road network for driving | 5.48 | 0.871 |

| Extent of connection to CSA farm via road network for biking/walking | 4.93 | 1.308 | |

| Extent of connection of public transport system to the CSA farm | 3.90 | 1.659 | |

| CSA-external proximity | Operationalized proximity item in survey | Mean | Standard deviation |

| Social proximity between members and CSA-external actors | Agreement that attitudes of the CSA are in general positive | 4.26 | 1.300 |

| Cognitive proximity between CSA-external actors and CSA members | Agreement that local interest in CSA is increasing in recent years | 4.25 | 1.552 |

| Agreement that CSA model is easy to understand for CSA-external actors | 3.28 | 1.557 | |

| Agreement that media often reports about CSAs * | 2.03 | 1.202 | |

| Organizational proximity between CSA-external actors and CSA members | Agreement to support/impediment by CSA-external actors (e.g., by governmental organizations, agricultural associations, food businesses, farmers, other CSAs, NGOs, private actors) ** | ||

| Agreement that the CSA should cooperate with dominant actors and organizations of the food system and encourage them to become more sustainable * | 3.34 | 1.797 | |

| Institutional proximity between CSA-external actors and CSA members | Agreement that the CSA should stay independent and small-scale, to be an alternative to the production and market mechanisms of the dominant actors of the food system * | 4.57 | 1.846 |

| Agreement that the CSA should not adapt to the production and market mechanisms of the dominant actors of the food system, to grow faster and gain power * | 5.10 recoded | 1.207 | |

| Geographical proximity between CSA farm and urban area, infrastructure, and agricultural land | Extent of suitability of land and climate for agricultural production | 5.33 | 0.829 |

| Extent of proximity of the CSA farm to the city * | 4.58 | 1.340 | |

| Extent of services nearby the CSA farm | 3.16 | 1.646 | |

| Extent of other community activities nearby the CSA farm | 3.28 | 1.575 | |

| Extent of networking opportunities nearby the CSA farm | 3.19 | 1.446 |

| Factor Loadings ▾ | Principal Components ▸ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal component 1: Social–cognitive proximity among CSA members | ||||||

| Connection with CSA farmer(s) (CSA-internal social proximity) | 0.845 | |||||

| Connection with CSA community (CSA-internal social proximity) | 0.682 | |||||

| Empathy for CSA ideas (CSA-internal cognitive proximity) | 0.675 | |||||

| Principal component 2:CSA farm’sgeographic proximity toCSA members and land | ||||||

| Road for biking/walking (CSA-internal geographical proximity) | 0.797 | |||||

| Road for driving (CSA-internal geographical proximity) | 0.724 | |||||

| Suitability of land (CSA-external geographical proximity) | 0.679 | |||||

| Public transport (CSA-internal geographical proximity) | 0.552 | |||||

| Principal component 3: CSA farm’s geographic proximity to external structures and resources | ||||||

| Community activities nearby (CSA-external geographical proximity) | 0.793 | |||||

| Services nearby (CSA-external geographical proximity) | 0.748 | |||||

| Networking nearby (CSA-external geographical proximity) | 0.687 | |||||

| Principal component 4: CSA-external social–cognitive proximity | ||||||

| Positive attitudes about CSA (CSA-external social proximity) | 0.742 | |||||

| Local interest in CSA (CSA-external cognitive proximity) | 0.720 | |||||

| Understanding CSA model (CSA-external cognitive proximity) | 0.624 | |||||

| Principal component 5: Institutional proximity among CSA members | ||||||

| Support of the new food market (CSA-internal proximity) | 0.842 | |||||

| Independence from the regular market (CSA-internal proximity) | 0.578 | |||||

| Traceability and transparency (CSA-internal proximity) | 0.540 | |||||

| Eigenvalue | 2.068 | 2.019 | 1.887 | 1.766 | 1.617 | |

| % of Variance | 12.928 | 12.620 | 11.791 | 11.039 | 10.106 | |

| Cumulative % | 12.928 | 25.548 | 37.340 | 48.379 | 58.485 | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.696 | 0.646 | 0.723 | 0.636 | 0.546 | |

| No. | Variables | B 1 | Standard Error 2 | β 3 | SIGNIFICANCE 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 5.574 | 0.160 | 0.000 | ||

| 1 | Principal component 1 | 0.248 | 0.052 | 0.330 | 0.000 |

| 2 | Principal component 2 | 0.031 | 0.057 | 0.041 | 0.587 |

| 3 | Principal component 3 | −0.050 | 0.053 | −0.066 | 0.350 |

| 4 | Principal component 4 | 0.200 | 0.062 | 0.264 | 0.002 |

| 5 | Principal component 5 | 0.115 | 0.053 | 0.144 | 0.032 |

| 6 | Country: Japan | 0.039 | 0.174 | 0.021 | 0.823 |

| 7 | Country: Norway | 0.108 | 0.139 | 0.070 | 0.436 |

| 8 | Age: <24 | −1.038 | 0.371 | −0.193 | 0.006 |

| 9 | Age: 25–44 | −0.065 | 0.124 | −0.040 | 0.601 |

| 10 | Age: >65 | −0.047 | 0.153 | −0.027 | 0.758 |

| 11 | Gender: Male | −0.251 | 0.118 | −0.145 | 0.035 |

| 12 | Employment: Full-time | −0.086 | 0.151 | −0.050 | 0.572 |

| 13 | Employment: Part-time | 0.104 | 0.167 | 0.050 | 0.533 |

| 14 | Employment: Self-employed | −0.098 | 0.165 | −0.048 | 0.552 |

| 15 | Employment: Other | −0.014 | 0.227 | −0.004 | 0.952 |

| CSA Independence from Dominant Structures | CSA Adaption to Dominant Structures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Total (n = 209) | 4.57 | 1.864 | 1.70 | 1.282 |

| Austria | 5.54 | 0.878 | 1.65 | 1.215 |

| Japan | 3.19 | 2.239 | 1.81 | 1.500 |

| Norway | 4.40 | 1.797 | 1.68 | 1.282 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gugerell, C.; Sato, T.; Hvitsand, C.; Toriyama, D.; Suzuki, N.; Penker, M. Know the Farmer That Feeds You: A Cross-Country Analysis of Spatial-Relational Proximities and the Attractiveness of Community Supported Agriculture. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11101006

Gugerell C, Sato T, Hvitsand C, Toriyama D, Suzuki N, Penker M. Know the Farmer That Feeds You: A Cross-Country Analysis of Spatial-Relational Proximities and the Attractiveness of Community Supported Agriculture. Agriculture. 2021; 11(10):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11101006

Chicago/Turabian StyleGugerell, Christina, Takeshi Sato, Christine Hvitsand, Daichi Toriyama, Nobuhiro Suzuki, and Marianne Penker. 2021. "Know the Farmer That Feeds You: A Cross-Country Analysis of Spatial-Relational Proximities and the Attractiveness of Community Supported Agriculture" Agriculture 11, no. 10: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11101006

APA StyleGugerell, C., Sato, T., Hvitsand, C., Toriyama, D., Suzuki, N., & Penker, M. (2021). Know the Farmer That Feeds You: A Cross-Country Analysis of Spatial-Relational Proximities and the Attractiveness of Community Supported Agriculture. Agriculture, 11(10), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11101006