An Analysis of Livelihood-Diversification Strategies among Farmworker Households: A Case Study of the Tshiombo Irrigation Scheme, Vhembe District, South Africa †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Study Area

3.2. Sampling Size and Sample Technique

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Ethics Statement

3.5. Method of Analysis

3.6. Estimating the Determinants of Farmworkers’ Livelihood Diversification: The Binary Probit Regression Model

3.7. Estimating the Determinants of Farmworkers’ Livelihood-Diversification Strategies

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

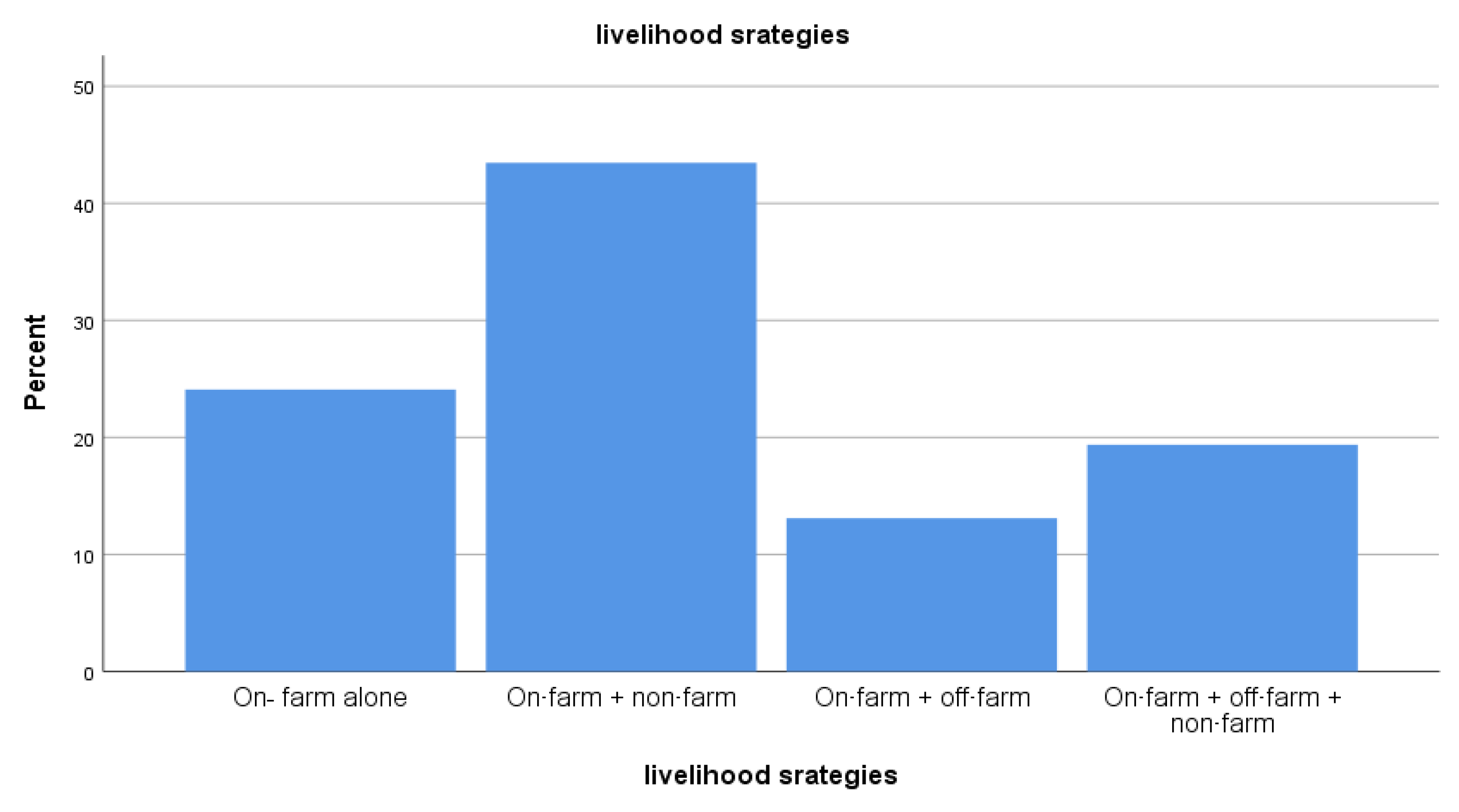

4.2. Irrigation Farmworkers’ Livelihood-Diversification Strategies

5. Discussion

5.1. Determinants That Influence Livelihood Diversification among Irrigation Farmworkers

5.2. Factors That Influence the Choice of Livelihood-Diversification Strategies

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

- Policymakers should design policies that are sensitive to laborers’ household-level characteristics in promoting livelihood income diversification.

- Rural development strategies should promote non-farm and off-farm activities in rural areas, as they could positively affect the income-generating capacity of irrigation scheme laborers.

- Policymakers should design policies that encourage engagement in informal land-lease contracts to encourage land rental market participation by both farm employers and employees in the rural areas of Tshiombo Village.

- Policymakers need to focus on the most suitable activities for supporting a sustainable livelihood outcome among rural irrigation scheme farmworkers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burney, J.A.; Naylor, R.L.; Postel, S.L. The case for distributed irrigation as a development priority in sub-Saharan Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12513–12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Averbeke, W.; Denison, J.; Mnkeni, P. Smallholder irrigation schemes in South Africa: A review of knowledge generated by the Water Research Commission. Water SA 2011, 37, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision; Esa Working Paper; pp. 1838–2521. FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fanadzo, M.; Ncube, B. Challenges and opportunities for revitalising smallholder irrigation schemes in South Africa. Water SA 2018, 44, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Koppen, B.; Nhamo, L.; Cai, X.; Gabriel, M.J.; Sekgala, M.; Shikwambana, S.; Tshikolomo, K.; Nevhutanda, S.; Matlala, B.; Manyama, D. Smallholder Irrigation Schemes in the Limpopo Province, South Africa; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2017; Volume 174. [Google Scholar]

- Dinku, A.M. Determinants of livelihood diversification strategies in Borena pastoralist communities of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayana, G.F.; Megento, T.L.; Kussa, F.G. The extent of livelihood diversification on the determinants of livelihood diversification in Assosa Wereda, Western Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2021, 8, 2525–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, A.; Yirgu, T.; Uncha, A. Determinants of rural livelihood diversification strategies among Chewaka resettlers’ communities of southwestern Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumba, M.; Palm, C.A.; Komarek, A.M.; Mutuo, P.K.; Kaya, B. Household livelihood diversification in rural Africa. Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F.; Allison, E. Livelihood Diversification and Natural Resource Access; Overseas Development Group, University of East Anglia: Norwich, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, O.O.; Sylvia, T.S. Analysis of rural livelihood diversification strategies among maize farmers in North West province of South Africa. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Eneyew, A.; Bekele, W. Determinants of livelihood strategies in Wolaita, southern Ethiopia. Agric. Res. Rev. 2012, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.L.; Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U. Shocks, household consumption, and livelihood diversification: A comparative evidence from panel data in rural Thailand and Vietnam. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Takasaki, Y. Natural disaster, poverty, and development: An introduction. World Dev. 2017, 94, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yan, Y.; Hei, W.; Yu, D.; Wu, J. Different household livelihood strategies and influencing factors in the inner Mongolian grassland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiphethi, M.N.; Jacobs, P.T. The contribution of subsistence farming to food security in South Africa. Agrekon 2009, 48, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moda, H.M.; Nwadike, C.; Danjin, M.; Fatoye, F.; Mbada, C.E.; Smail, L.; Doka, P.J. Quality of work life (QoWL) and perceived workplace commitment among seasonal farmers in Nigeria. Agriculture 2021, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, S.; Tavener-Smith, L. Seasonal food insecurity among farm workers in the northern cape, South Africa. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ossome, L.; Naidu, S.C. Does Land Still Matter? Gender and Land Reforms in Zimbabwe. Agrar. South J. Political Econ. 2021, 10, 344–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, G.W.; Ichoku, H.E.; Phil-Eze, P.O. Determinants of livelihood diversification strategies in Eastern Tigray Region of Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiassa, N. Determinants of Rural livelihood strategies: The case of rural Kebeles of Dire Dawa administration. Res. J. Financ. Account. Vol 2017, 8, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, B.; Lambrecht, I. Gender and Preferences for Non-Farm Income Diversification: A Framed Field Experiment in Ghana; IFPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mada, M. Small-scale Agriculture and it’s hope to food security in Africa: The case of kamba district in Ethiopia. Int. J. Mgmt. Res. Bus. Strat. 2015, 4, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wondim, A.K. Determinants and challenges of rural livelihood diversification in Ethiopia: Qualitative review. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. 2019, 11, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kassegn, A.; Endris, E. Review on livelihood diversification and food security situations in Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2021, 7, 1882135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olumeh, D.E.; Otieno, D.J.; Oluoch-Kosura, W. Effects of gender and institutional support services on commercialisation of maize in Western Kenya. Dev. Pract. 2021, 31, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaunga, S.; Mudhara, M. Analysis of Livelihood Strategies for Reducing Poverty Among Rural Women’s Households: A Case Study of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Int. Dev. 2021, 33, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Takahashi, D. Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept for Farmland Leasing and Custom Farming in Taiwan. Int. Assoc. Agric. Econ. 2018, 28, 277–326. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hochard, J.P. Poverty and the Spatial Distribution of Rural Population; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank Group: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kassem, H.S.; Alotaibi, B.A.; Muddassir, M.; Herab, A. Factors influencing farmers’ satisfaction with the quality of agricultural extension services. Eval. Program Plan. 2021, 85, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etuk, E.; Udoe, P.; Okon, I. Determinants of livelihood diversification among farm households in Akamkpa Local Government Area, Cross River state, Nigeria. Agrosearch 2018, 18, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Felkner, J.S.; Lee, H.; Shaikh, S.; Kolata, A.; Binford, M. The interrelated impacts of credit access, market access and forest proximity on livelihood strategies in Cambodia. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Mavedzenge, B.; Murimbarimba, F.; Sukume, C. Labour after land reform: The precarious livelihoods of former farmworkers in Zimbabwe. Dev. Chang. 2019, 50, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manase, K.C.; Takunda, C. The complexity of farmworkers’ livelihoods in Zimbabwe after the Fast Track Land Reform: Experiences from a farm in Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2019, 46, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, D.; Flandorp, C. Horticultural Development Plan for the Thulamela Local Municipality: Agricultural Overview; OABS Development (Pty) Ltd.: Paarl, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C. An introduction to logistic and probit regression models. Lect. Notes Univ. Tex. Austin 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.T.; Bhandari, H.; Gordoncillo, P.U.; Quicoy, C.B.; Carnaje, G.P. Diversification of rural livelihoods in Bangladesh. J. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 2015, 2, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tizazu, M.A.; Ayele, G.M.; Ogato, G.S. Determinants of rural households livelihood diversification strategies in kuarit district, West Gojjam zone of, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Int. J. Econ. Behav. Organ 2018, 6, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Lutomia, C.K.; Obare, G.A.; Kariuki, I.M.; Muricho, G.S. Determinants of gender differences in household food security perceptions in the Western and Eastern regions of Kenya. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1694755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goba, Z.Z. Review on Determinants of Rural Livelihood Diversification Strategies in Ethiopia. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2021, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loison, S.A. Household livelihood diversification and gender: Panel evidence from rural Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prowse, M. The determinants of non-farm income diversification in rural Ethiopia. J. Poverty Alleviation Int. Dev. 2015, 6, 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel, E.A. Rural livelihood diversification and agricultural household welfare in Ghana. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 3, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Gebreyesus, B. Determinants of livelihood diversification: The case of Kembata Tambaro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. J. Poverty Investig. Dev. 2016, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| Binary probit regression model | |

| y = 1 | Diversified from farm work |

| y = 0 | Not diversified from farm work |

| Multinomial logistic regression model | |

| Choices of livelihood-diversification strategies (J): | |

| j1 = On-farm alone | |

| j2 = On-farm + off-farm | |

| j3 = On-farm + non-farm | |

| j4 = On-farm + off-farm + non-farm | |

| Variables | Measures | Expected Sign |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Years | + |

| Gender | Male = 1; Female = 0 | +/− |

| Marital status | Married = 1; Single = 0 | + |

| Level of education | 1 = Formal education; 0 = non-formal education | + |

| Number of dependents | Number of dependents | + |

| Employment type | Permanent farmworker = 1; seasonal farmworker = 0 | +/− |

| Farming experience | Years | + |

| Agricultural training | Yes = 1; No = 0 | + |

| Savings | Rand (R) | + |

| Market access | Yes = 1; No = 0 | + |

| Leasing land from employer | Yes = 1; No = 0 | + |

| Independent Variables | Coefficients | Robust Std. Error | Marginal Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.002 |

| Gender | 0.554 | 0.221 | 0.218 ** |

| Marital status | −0.237 | 0.208 | −0.093 |

| Level of education | 0329 | 0.249 | −0.129 |

| Number of dependents | 0.134 | 0.046 | 0.052 ** |

| Employment type | −0.381 | 0.221 | −0.150 * |

| Years of farming experience | −0.033 | 0.010 | −0.013 *** |

| Agricultural training | 0.093 | 0.210 | 0.036 |

| Land leasing | 0.423 | 0.215 | 0.166 ** |

| Market access | 0.486 | 0.249 | 0.191 ** |

| Savings | 0.158 | 0.106 | 0.062 |

| Constant | −0.069 | 0.547 |

| Independent Variables | On-Farm Only | On-Farm and Off-Farm | On-Farm and Off-Farm & Non-Farm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Std. Err. | ME | Coef. | Std. Err. | ME | Coef. | Std. Err. | ME | |

| Age | −0.002 | 0.020 | −0.003 | −0.024 | 0.025 | −0.007 | −0.081 | 0.025 | −0.001 *** |

| Gender | 0.128 | 0.442 | 0.016 | 0.564 | 0.536 | 0.031 | 0.254 | 0.517 | 0.060 |

| Marital status | 1.358 | 0.430 | 0.209 *** | 0.409 | 0.536 | 0.259 | 1.039 | 0.517 | 0.017 ** |

| Level of education | 0.297 | 0.502 | 0.065 | −0.860 | 0.624 | −0.021 | 0.518 | 0.579 | −0.109 |

| Number of dependents | −0.113 | 0.093 | −0.009 | −0.226 | 0.115 | −0.037 ** | −0.157 | 0.111 | −0.016 |

| Employment type | 0.461 | 0.464 | 0.073 | −0.005 | 0.542 | −0.090 | 0.454 | 0.563 | −0.022 |

| Leasing land from employer | 0.958 | 0.449 | 0.147 | 0.582 | 0.531 | 0.164 | 1.354 | 0.573 | 0.114 ** |

| Farming experience | 0.030 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0.026 | −0.012 | 0.089 | 0.027 | 0.002 *** |

| Agricultural training | −0.105 | 0.424 | −0.061 | 1.307 | 0.619 | 0.058 ** | 0.128 | 0.495 | 0.119 |

| Savings | 0.213 | 0.212 | 0.016 | 0.338 | 0.259 | −0.071 | 0.382 | 0.256 | 0.021 |

| Market access | −0.571 | 0.513 | −0.074 | 0.233 | 0.626 | 0.131 | 1.416 | 0.670 | 0.064 ** |

| Constant | −0.951 | 1.09 | −1.163 | 1.464 | 1.564 | 1.221 | |||

| Variables | On-Farm Alone | On-Farm + Non-Farm | On-Farm + Off Farm | On-Farm + Off-Farm + Non Farm | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.41 | 47.06 | 49.28 | 39.95 | *** |

| Number of dependents | 5.08 | 5.48 | 4.68 | 4.81 | ns |

| Total house-hold monthly income (ZAR) | 1667.82 | 2325.13 | 2546.50 | 2586.40 | ns |

| Years of farming experience | 17.30 | 14.73 | 18.76 | 19.45 | ns |

| Livelihood | Diversification | Strategies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Measure | On-Farm Alone (n = 46) | On-Farm + Non-Farm (n = 83) | On-Farm+ Off-Farm (n = 25) | On-Farm + Off-Farm + Non-Farm (n = 37) | n | X2 Sig. Level |

| Gender | Woman (%) | 21.7 | 46.7 | 12.5 | 19.2 | 120 | ns |

| Male (%) | 28.2 | 38.0 | 14.1 | 19.7 | 71 | ||

| Marital status | Single (%) | 16.0 | 54.0 | 12.0 | 18.0 | 100 | *** |

| Married (%) | 33.0 | 31.9 | 14.3 | 20.9 | 91 | ||

| Level of education | No formal education (%) | 22.4 | 48.2 | 18.8 | 10.6 | 85 | ** |

| Formal education (%) | 25.5 | 39.6 | 8.5 | 26.4 | 106 | ||

| Type of farmworker | Seasonal farmworker (%) | 24.2 | 42.2 | 12.5 | 21.1 | 128 | ns |

| Permanent farmworker (%) | 23.8 | 46.0 | 14.3 | 15.9 | 63 | ||

| Leasing land | No (%) | 18.2 | 53.2 | 19.5 | 9.1 | 77 | *** |

| Yes (%) | 28.1 | 36.8 | 8.8 | 26.3 | 114 | ||

| Agricultural training | No (%) | 25.7 | 50.0 | 7.1 | 17.1 | 70 | ns |

| Yes (%) | 23.1 | 39.7 | 16.5 | 20.7 | 121 | ||

| Market access | No (%) | 24.2 | 41.8 | 12.4 | 21.6 | 153 | ns |

| Yes (%) | 23.7 | 50.0 | 15.8 | 10.5 | 38 |

| Variables | Collinearity Statistics | |

|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | |

| Age | 0.570 | 1.755 |

| Gender | 0.840 | 1.190 |

| Marital status | 0.870 | 1.150 |

| Level of education | 0.629 | 1.591 |

| Number of dependents | 0.909 | 1.100 |

| Employment type | 0.851 | 1.175 |

| Years of farming experience | 0.745 | 1.343 |

| Agricultural training | 0.906 | 1.104 |

| Land leasing | 0.826 | 1.210 |

| Market access | 0.945 | 1.058 |

| Savings | 0.909 | 1.101 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mudzielwana, R.V.A.; Mafongoya, P.; Mudhara, M. An Analysis of Livelihood-Diversification Strategies among Farmworker Households: A Case Study of the Tshiombo Irrigation Scheme, Vhembe District, South Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111866

Mudzielwana RVA, Mafongoya P, Mudhara M. An Analysis of Livelihood-Diversification Strategies among Farmworker Households: A Case Study of the Tshiombo Irrigation Scheme, Vhembe District, South Africa. Agriculture. 2022; 12(11):1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111866

Chicago/Turabian StyleMudzielwana, Rudzani Vhuyelwani Angel, Paramu Mafongoya, and Maxwell Mudhara. 2022. "An Analysis of Livelihood-Diversification Strategies among Farmworker Households: A Case Study of the Tshiombo Irrigation Scheme, Vhembe District, South Africa" Agriculture 12, no. 11: 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111866