1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Description of the Evolution of the Wine Market

Wine is one of the leading products in the Italian agri-food system. Today, the production of quality wines requires a highly complex process that depends on various factors, such as the pedoclimatic characteristics of the area where the vineyards are situated, as well as their quality, the terroir, and the methods of cultivation in the vineyard and production in the cellar.

From the 1980s to the present day, several factors have contributed to the decline of alcoholic beverage sales in Europe, as in many other countries all over the world (e.g., the US, Australia, etc.), with consumers progressively shifting their interest towards quality wines. In fact, over the years, the wine consumption trend has been influenced by several factors, including economic factors, public health policies, the emergence of new drinks, the homogenization of consumption patterns, increased preference for non-alcoholic drinks, advertising, public opinion, and changes in consumers’ lifestyles, among others [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The reasons behind wine-consumption choices have evolved considerably over the last 40 years, as the focus has moved from the consumption of wine simply as an alcoholic beverage (and, in some countries with a winemaking tradition, including France and Italy, drinking wine as a traditional part of a meal) to the “pleasure” of drinking a quality wine. Over the past two decades, many consumers have switched their consumption preferences toward premium alcoholic beverages, i.e., beverages that have a higher quality and price [

6,

7]. Due to various influences—including increasing wealth in some segments, more options for high-quality products and categories, and a consumer interest in, and appreciation of, production methods and origins [

8]—consumers have become increasingly willing to spend more on higher quality products across the wine, spirits, and beer categories [

6]. Finally, more recently, wine has progressively become a symbol of belonging among young consumers who today constitute the so-called “community of wine lovers” [

9]. These consumers love to gain knowledge and take an interest in the history of a winery or a wine and to know its territory of origin and food pairings. They exchange advice on wines, combinations, and prices, so much so that a progressive trend towards “brand democratization” has been observed [

10]. This change in consumption habits is due the combination of at least three causes. First, there is a new segment of wine consumers, made up of so-called Millennials and Zoomers, also identified as “digital natives” (being the first social generation to have grown up with access to the Internet and to portable digital technology). Second, there has been a rapid spread of the use of the Internet, social networks, and other digital channels (e-commerce) for the communication and purchase of products, including foods and wines [

11]. Finally, there has been a further acceleration in the use of the Internet and social networks in food communication and purchasing as a result of concerns and restrictions (e.g., lockdowns) due to the COVID-19 pandemic [

6].

1.2. Country of Origin Effect and Italian Wine Classifications

Wine region, organoleptic characteristics, and country of origin effect (COE) are the main elements that characterize a quality wine. Since 1965, the COE, also known as the “made-in image” or “nationality bias,” has been considered a psychological effect describing how consumers’ attitudes, perceptions, and purchasing decisions are influenced by a product’s country of production. This can refer to where a company has its production base, to where a product is designed/developed, or to other forms of value creation linked to a specific country [

12,

13,

14,

15].

In Europe, as far as food products are concerned (and therefore also wines), “quality certifications” have been established [

16]. Quality, identified by the certifications recognized at the European level, is mainly based on the presence of particular characteristics linked to the production area, the territory of origin, the production process, and the quality of the product (e.g., the absence, or very low quantity, of residues of chemical substances) [

17]. With regard to wines, in Italy, there are wine classifications that are part of the Italian appellation system for wine, recognized by the government [

18]. Specifically, there are four Italian wine classifications: Vino da Tavola (VdT); Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT or Typical Geographical Indication); Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC or Controlled Designation of Origin); and Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG or Guaranteed and Controlled Designation of Origin). The IGT, DOC, and DOCG designations certify the area of origin of a wine and delimit the area of the harvesting of the grapes used for the production of the wines to which the mark is affixed. The IGT appellation was created to recognize the unusually high quality of the class of wines known as “Super Tuscans”. However, IGT wines do not meet the requirements of the stricter DOC or DOCG designations, which are generally intended to protect traditional wine formulations (such as the famous Chianti wine or Barolo wine). The DOC appellation, therefore, designates a quality and renowned wine, whose characteristics are related to the natural environment and human factors and comply with a particular production specification which has been approved by ministerial decree. It is considered broadly equivalent to the former “French vin de pays” classification (now Protected Geographical Indication (Indication Géographique Protégée)) under EU law.

In fact, the intrinsic characteristics of these quality wines cannot be replicated because they have been shaped by their territories of origin, which give the products their reputation [

8].

1.3. Sicily’s Major Wine Regions: The Etna Valley’s Viticulture and Wines

Sicily is a wine-growing area of high strategic value at the national level. The area cultivated with vineyards in Sicily is approximately 103,000 ha, of which 5% is in the mountains, 65% is in the hills, and 30% is on the plains.

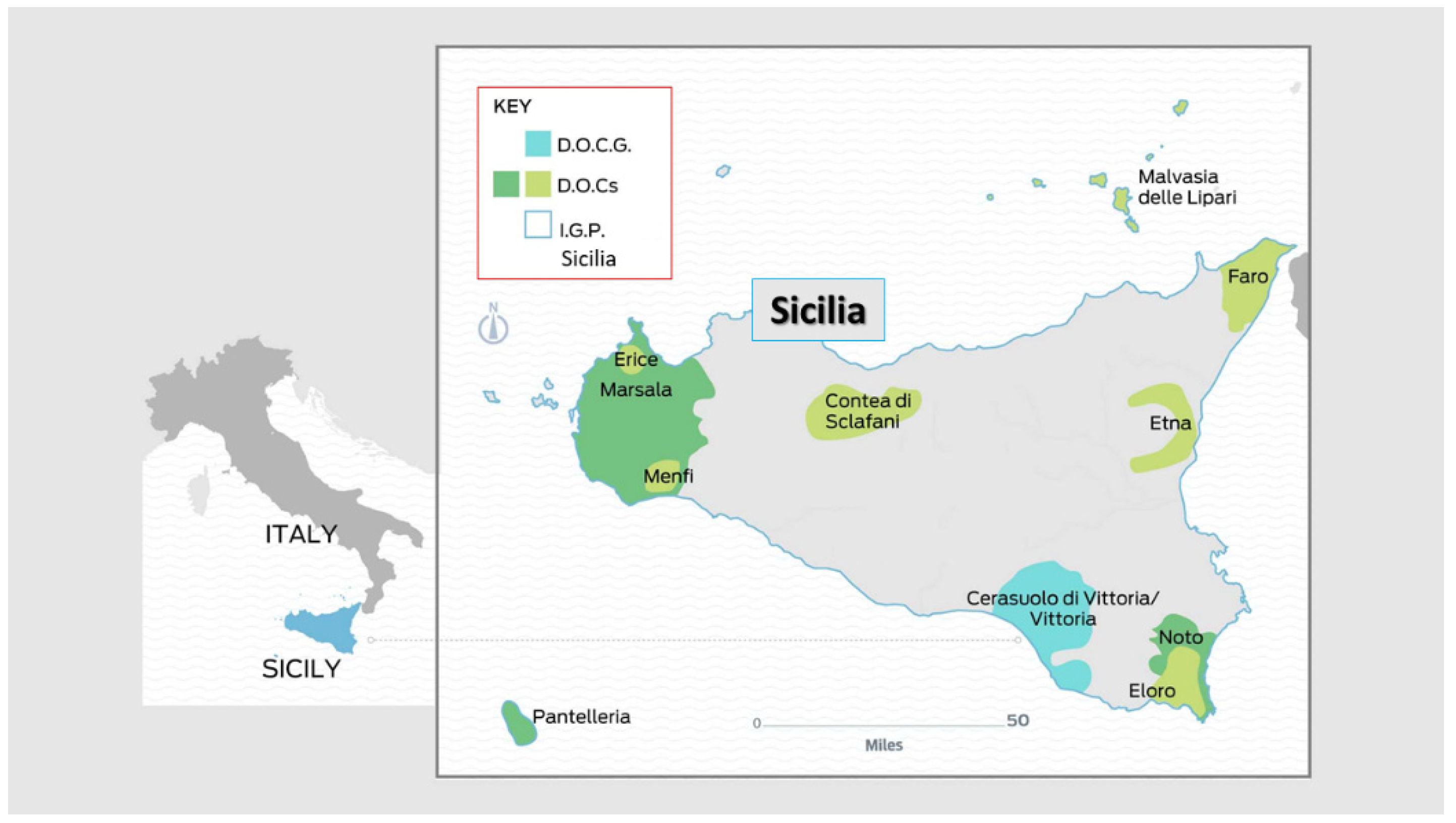

The wine-growing areas of Sicily have significantly different characteristics due to the numerous natural differences that characterize the various areas of the island. In fact, these territories are real agro-ecosystems that are profoundly different from each other (in terms of altitude, proximity to the sea, characteristics of the terrain, presence of strong winds, etc.). These regions are: Lipari (Eolian islands); Faro; Etna; Noto (and Eloro); Vittoria; Sclafani; and Trapani (Erice, Marsala, Menfi, and Pantelleria) (

Figure 1).

The wines produced in the Sicily’s major wine regions are proof of these differences; for example, wines from Passito di Pantelleria DOCG (island of Pantelleria, TP), the Etna Rosso DOC (Etna volcano valley, CT), the Cerasuolo di Vittoria DOCG (Vittoria, RG), and the Marsala Vergine DOC (Marsala, TP) differ significantly in their characteristics but are all qualitatively remarkable. It is not by coincidence that, in Sicily, there have been 13 “wine routes” established to date, characterized by as many different territories and landscapes, which are unique and inimitable [

2,

19].

One of these Sicilian territories is the Etna volcano valley (Catania, Sicily), which has an extremely high level of agricultural characterization. Etna is a young mountain, formed 500,000 years ago, that erupted from the seabed of a now disappeared gulf, in what today is the Plain of Catania. It is one of the most active volcanoes in the world. It is currently 10,912 ft high, although this varies owing to eruptions at the summit, and covers an area of 45 km in diameter (28 miles). These dimensions make it the most impressive terrestrial volcano in Europe and the entire Mediterranean area [

20].

The unique volcanic soil favors agriculture, with vineyards and orchards distributed along the lower slopes of the mountain and the wide Plain of Catania to the south, although the agricultural practices are carried out using highly specialized techniques [

20]. The history of viticulture in this territory, with its unique ecosystem and pedoclimatic characteristics, began with a specific geological event that lasted 700,000 years and created the Etna volcano, which is the highest in the European area. The “

alberello” vine cultivation [

8,

20] has remained unchanged for 30 centuries (the Sicilian traditional trellising system “

alberello” is typical of rural areas: vines are trained to low trunks, with bunches located closer to the soil, and each vine is at an equal distance from the surrounding ones). In the nineteenth century, the Etna valley was the most important wine area of Sicily, with vineyards occupying more than half of the land, reaching altitudes over 1000 m. Wine continuously shapes the landscape: the black lava stone terraces allow the vine to climb in increasingly impervious places. Subsequently, due to the phenomenon of the widespread emigration of Sicilians all over the world caused by serious economic problems and infrastructural deficiencies, as well as by the

Phylloxera virus, the production of wine in this territory decreased drastically, in terms both of quality and quantity. Only in the last 20 years, thanks to the efforts of a few enlightened people (entrepreneurs, oenologists, farmers), has there been a rebirth of viticulture in the Etna valley, which has one of the most appreciable European terroirs. These years represent a particularly prosperous period for the local rural economy. The Etna volcano was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013, due partly to the so-called “heroic viticulture” practiced (a term used due to the great difficulties in cultivation and harvesting faced by winemakers in such “extreme” territories) [

8,

20,

21]. Some other examples of UNESCO awards for heroic viticulture include the following: in 1997 and 2000, respectively, the Cinque Terre National Park in Italy and the Wachau Region in Austria were recognized as cultural landscapes (also due to the presence of vineyards); in 2001, the Douro Region in Portugal was recognized as a wine-growing landscape for the first time, followed in 2004 by the Ilha do Pico in the Azores Islands, the Lavaux area in Switzerland in 2007, and finally, the Langhe, Roero, and Monferrato in 2014; the same year also saw the recognition of the

alberello vine cultivation of the island of Pantelleria (Sicily, Italy), the world’s first cultural element of an agricultural nature to be recognized by UNESCO.

Due to the intrinsic characteristics derived from the territory or origin, Sicilian Etna Rosso DOC wine is a product of high quality and character. In 2018 and 2019, some brands won prizes and awards in important international wine competitions. Nevertheless, this wine is not known and purchased as much as it deserves, either in Italy or abroad. This may be in part because of the sensorial traits (it is a prominent wine, soft, intense, dry, full-bodied, and with a significant alcoholic content of about 12.5%). Additionally, non-expert consumers or foreign consumers may have difficulty justifying the price, which is usually medium to high, because they do not know the difficulties of producing wine in the Etna valley and the reasons for the strong traits of the wine. However, strengthening these enterprises would help the economic and social growth of the entire Etnean territory. Therefore, effective policies are necessary to reposition the product in the market that leverage the particular characteristics of wine, due to its extremely strong link with the territory, proposing them as strengths rather than limitations.

1.4. Advances and Gaps in the Existing Literature and the Study’s Aims and Objectives

The brand and information regarding the characteristics of wines/cellars and territories of origin—available on the label or obtained through advice from wine influencers (storytelling)—are the main elements taken into consideration by demanding consumers [

8,

12]. This has also been confirmed by recent studies, which show that the consumption of quality wines has increased in recent years among certain groups of consumers (with particular characteristics and lifestyles) [

8,

9]. Wine is a product with significant symbolic components, and the territory of origin is crucial for its connotation and recognizability [

8,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Less experienced consumers, on the other hand, correlate quality with price [

7,

26], mainly using the information on labels or, if possible, asking the retailer.

According to the literature, a food product is more identifiable when it is presented alongside its territory of origin [

8,

20,

22,

23]. Some authors have highlighted how rational, emotional, and hedonistic components often coexist in consumer choices and influence both their level of satisfaction and their choices. They have also highlighted the importance of sensory marketing in the food products sector. This occurs especially with wine. In fact, other authors have demonstrated that a product’s origin-based context and correlated activities, such as wine tourism, green tourism, slow tourism, etc., through strong emotional involvement, evoke positive emotions and lead to purchase intentions [

24,

25].

A wine regions with strong territorial character and impressive elements of uniqueness can be seen as a significant asset for wine producers, who are able to exploit the link between the brand and the territory as a further element of differentiation in the market and of the creation of added value. Given the high competitiveness of the wine sector at an international level, these identity elements, if well exploited and communicated, could generate further qualitative characteristics of value, which consumers could be willing to pay more for.

To the best of our knowledge, the existing literature on the brand–land link for high-quality wines produced in the extreme Sicilian wine region of the Etna valley is scarce [

20,

27]. The strengthening of these enterprises seems crucial in terms of the economic and social development of a rural area—a World Heritage Site—which is at risk of abandonment but is of extremely high value to the local population [

28]. However, new elements relevant to designing effective policies and strategies to reposition the product in the market using its strong link with the territory have not been highlighted to date. By examining the brand–land link in a real context, and by exploring real territory–wine development factors, it will be possible to provide producers of iconic and distinctive wines, such as those of the Etna valley, with useful information, based on empirical data, which can help them to formulate effective marketing and positioning strategies (product, price, place, promotion). Another aim of this study is to contribute to the scientific literature by providing feasible development scenarios for small wine firms producing valuable wines in rural territories that are still economically underdeveloped. The findings may be of interest for researchers studying the same topics in similar wine territories elsewhere.

Therefore, in this scenario, the issues that need to be addressed are as follows:

Q1: Does a relationship exist between brands and the territory/place of production of quality wines? Are producers and stakeholders aware of this link?

Q2: What components define this relationship? Are there development factors that can be addressed?

Q3: Can the brand–land relationship increase the added value of this wine and of iconic wines in general, and, if so, how?

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to study the existence and characteristics of the brand–land link for the wines of the Etna territory. Specifically, the objectives of this study are as follows:

O1: To ascertain the existence of a relationship between the company brand and the territory of origin (brand–land link) in the Sicilian wine-growing area of the Etna valley and the level of awareness of producers and stakeholders with respect to the recognizability of the wines and the brand–land link.

O2: To highlight any development factors by type, characteristics (strengths, weaknesses, reliability, importance), and their applicability, desirability, reliability, and importance.

O3: To highlight difficulties and opportunities for wine producers of Etna Rosso DOC wine using the brand–land link as an added value for the wines and cellars of Etna and to create a new value-chain design specific to the Etna valley wines but that can be generalizable and applicable in similar wine regions for value creation.

This study will provide empirical evidence of the current situation in the Sicilian Etna wine territory. This attempt to achieve the aforementioned objectives will contribute to the body of research and benefit the cluster of small wine-growing enterprises operating in rural and extreme areas of high environmental, aesthetic, and social value. Theoretical contributions are also important in empirical studies such the present work [

29]; therefore, the theoretical framework on which this study was developed is described extensively in

Section 2. Further, in addition to the practical results, which are useful for producers and all stakeholders in the area, the study aims to propose a theoretical generalization of the value chain, with external factors being integrated that combine to increase the margins of wine enterprises.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Delphi Method

For this study, the policy Delphi (PD) method, a variant of the general Delphi method [

49], was applied. This variant will be described in the

Section 3.2 after having first described the base Delphi method. The Delphi method was developed in the 1950s in the US in the context of problem-solving studies and evaluation techniques focusing on decision-making [

49]. The first research paper on the Delphi method was published in 1969 after many years of experimentation in the research offices of the Rand Corporation [

49]. The goals of the Delphi method are to describe a variety of alternatives to a policy issue and to provide a constructive forum through which consensus may be achieved. The Delphi method consists of exposing one or more topics to a panel of experts who are able to give precise evaluations, increasingly convergent with each other, assisted by a process of validation of the observations [

50]. It has also been applied in the context of large, complex problems plagued with uncertainty and in situations where causation cannot be established [

50]. This method is considered one of the most suitable for addressing long-term forecasting problems for which deterministic and quantitative techniques do not achieve satisfactory results [

51]. Furthermore, studies in the literature on this method have shown that it has particular advantages over other types of group discussions that use interactive cognitive processes (e.g., focus groups) in the case of issues being addressed for which the most significant information is provided via the judgment of experts [

22]. It is largely used for the implementation of action strategies, to identify possible scenarios to be considered to solve a problem, and to carry out feasibility assessments for private or public strategies (in local development programs for example) [

52,

53]. The peculiarity of this method lies in structuring the analysis of a phenomenon, a contingent problem, or controversial issues related to the same policy related debate with the aim of overcoming ideological or opportunistic conflicts and obtaining consensus among a heterogeneous group of stakeholders or experts [

51,

52,

53,

54]. It is a type of analysis used not only as a forecasting method but also as a procedure for verifying and perfecting consensus and decision-making aimed at seeking innovative solutions [

55]. Thanks to this methodology, it is possible to obtain, within a group of experts, the consensual opinion most relevant to the reality of the reference context in order to correctly elaborate a scenario (and not just to obtain an answer to a single question) [

55,

56]. For this reason, this method falls under the general category of “consensus development techniques,” which in turn are within the general grouping of action research approaches. Consensus techniques are typically applicable when there is limited evidence concerning the specific topic of interest, or when the existing evidence is contradictory [

56]. Moreover, it is applicable in cases where little prior research exists or where advantage could be realized via the collective subjective judgment of experts [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

It is important to note that unanimity is not the objective of this methodology: achieving 70% consensus among panel members is considered the standard.

The Delphi method is predominantly qualitative in nature, but it can have a quantitative component depending on the specific application [

53,

54,

55,

56]. This technique envisages successive phases of data collection, characterized by the use of social research tools of various kinds (e.g., questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, etc.), and aims for a progressive exploration and evaluation of the theme investigated [

53,

54,

55]. To this end, the researcher has the task of mediating the comparison and evaluation of the opinions collected, leading to the synthesis of the judgements collected in each round with the results of the previous round [

56,

57].

In designing the panel, the researcher must decide which groups of experts will best be able to satisfy the study purpose, how many individuals should be included in each group, and what criteria should be used for membership [

56,

57,

58].

Panel members are asked specific questions and provide responses that the researcher consolidates and feeds back to the panel in a series of rounds until consensus is achieved [

25,

58]. Delphi panels are based on two principles critical to executing the procedure: anonymity (to encourage freedom of expression); and feedback (panel discussions are summarized and fed back to members) [

50,

53]. With regard to “anonymity,” keeping panel members isolated from each other allows each individual freedom of expression without outside pressure or influence. In general, averaging the opinions of individuals collected separately is often more accurate than opinions reached through face-to-face discussion (as in the case of focus groups, which are carried out for different aims) because of dominant participants and groupthink, which can limit the effectiveness of face-to-face groups. Using the web and conducting panel business by e-mail via the researcher/facilitator is particularly effective, primarily in order to maintain this privacy and confidentiality [

25,

55,

57]. All panel members should communicate individually with the researcher. The researcher needs to be extremely careful in ensuring that communication with each panel member is maintained on this individual basis. With regard to “feedback,” panel deliberations begin with one or more questions to individual members. Responses to the question(s) regarding the initial topic(s) are collected and consolidated by the researcher/facilitator and then returned to panel members in a series of iterations called “rounds” until consensus is reached. In each iteration, panel members are asked to review the outcome of the previous round and either agree with that outcome or recommend changes, along with their rationale for making these changes [

58].

3.2. The Policy Delphi (PD) Method

The methodology described above refers to the standard Delphi approach, in which the panel is composed of experts. This methodology can be adapted to the PD variant, in which both stakeholders and policy-makers are involved and invited to evaluate future events that partly depend on their own actions. PD has particularly interesting applications in the field of public decision-making and public administration, especially in relation to the development of policies, because it generates structured communication flows with highly specific content without generating redundancy of information. Additionally, it allows decision-makers to share the exploratory phase of the decision-making process, which gives rise to alternative forms of political participation [

59]. The PD method includes four phases [

25,

59]: definition of the study’s objects (phase 1); choice of the reference panel of participants (phase 2); two or more rounds of data collection (by using two or more questionnaires) and analysis of the partial results (phase 3); and evaluation of the results (phase 4). The main features that distinguish PD from the standard Delphi approach are the greater breadth and heterogeneity of the panel used, which also includes public administrators, political actors, business executives, etc. According to literature, the panel of participants should be selected according to criteria of representativeness rather than technical expertise [

25,

59], focusing in particular on:

a different idea of consensus (the decision-maker should not have a unanimous opinion, but an exploded map of different points of view to choose from);

the articulation of the items into proposals, objectives, and lines of action, the content of which can be performed by the participants themselves according to pre-established rules and supported by arguments for or against;

the introduction of different evaluation criteria (in addition to the probability of the realization of a given event or political decision, its desirability and feasibility are also assessed); and

a more complex organizational structure.

3.3. Choosing the Reference Panel of Participants

The PD panel participants should be selected to represent a wide range of opinions; therefore, choosing a suitable panel of experts, stakeholders, and policy-makers for such an analysis is crucial. Depending on the policy issue area, the number and type of participants will vary. A typical PD panel size may range from 10 to more than 100 participants. Akins et al. [

58] noted that panels have been conducted of just about any size. In fact, as the complexity of the policy issue increases, the sample size needs to be larger to include the entire range of participants on both sides of the policy issue debate. The type of participants selected includes both formal and informal stakeholders who have a vested interest in the policy issue. These participants should have varying degrees of influence, hold a variety of positions, and be affiliated with different groups. Researchers should be attentive to balancing membership across groups as much as possible, as one particular expert group could dominate the process to some degree if it were significantly larger than the others [

25,

58,

59,

60].

For this study, it was desirable that the panel of experts, stakeholders and policy-makers include members of communities and groups with different interests. The differences among the panelists were intended, as this guaranteed the creation of a heterogeneous group with respect to the topic under study, allowing it to provide useful and diverse observations and opinions which were necessary for the purpose of the survey. The heterogeneity of the panel also concerned the number of years of experience of each participant in the wine sector and the issues addressed, and this is precisely the characterizing element of the Delphi method, which is intended to identify innovative solutions through the enhancement of diversity to achieve a certain level of competence.

The panel used for this survey, selected using a “reasoned sampling” approach, comprised 169 individuals with the following institutional roles or occupation:

- ○

wine producers;

- ○

wine experts (wine journalists, wine influencers/bloggers, wine marketing experts, distributors, etc.);

- ○

sommeliers;

- ○

oenologists;

- ○

researchers;

- ○

policy-makers;

- ○

local administrators;

- ○

entrepreneurs in the tourist and agro-food sector (with a relevant role in the territory); and

- ○

other stakeholders.

To select the respondents according to these rationales, professional networks and official databases were used to extract a potential sample of participants.

From these lists, a sample was extracted using the stratified sampling method with random extraction from each homogenous stratum. A formal invitation to take part in this study was sent to potential participants. All panelists remained anonymous during the phases of analysis and related feedback.

In line with other PD studies, there was a decline in participants between the first and last round: 169 participants completed the first round of the survey and 98 took part in round 2. According to the literature on the PD method, the process of iterations ends when findings reach saturation (no new elements emerge from the discussion) [

59,

60].

3.4. Rounds of Data Collection and Analysis of the Data

Although some applications of the PD method use in-person individual or group interviews, this study adopted emails in order to significantly reduce response times and postage costs. According to the literature, the number of rounds may range between two and five [

25].

In this study, the PD method provided sufficient information after two rounds, since no new elements emerged as a result of the stimuli provided in the final step of round 2 (the process had reached saturation). Therefore, only two formal questionnaires were prepared and administered to the panelists, one for round 1 (with the initial topics) and one for round 2 (with information from the outcomes of round 1); no need for a further questionnaire emerged because the process reached saturation after round 2.

The questionnaire used for round 1 was open-ended, as the aim was to explore the general opinions on the main topics of the research [

25,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. The results of the first round were used to prepare the subsequent questionnaire for round 2, the aim of which was to check the outcomes from round 1 [

25].

Specifically, round 1 (questionnaire 1) aimed to initiate, facilitate, and extend the discussion about the specific issues/topics under investigation. The topics—according to the objectives of the study—were developed through three months of desk-based research and collaboration among the authors and experts in the wine sector, as well as a pilot phase. The topics for round 1 were formulated to address all the study’s questions and objectives:

Q1, O1: Topic 1. What is the meaning of the brand–land link? What elements may contribute to valorizing the brand–land link for Etna Rosso DOC wine and the Etna valley?

Q2, O2: Topic 2. What are deficiencies of the territory and how can the territorial development be organized to valorize the link between brand (Etna Rosso DOC) and land (Etna valley)?

Topic 3. What are the economic impacts of the brand–land link for the winemakers and for the development of the territory? What are the development factors for winemakers and the territory? Provide possible solutions.

Q3, O3: Topic 4. What possibilities are there for enhancing the territory (e.g., wine tourism) and Etna Rosso DOC wine (e.g., wine tasting, guided consumption of the wine)? What about communication?

Topic 5. What are the main motivations for communicating the link between the wine and its territory of origin? Suggest effective communication strategies.

Topic 6. What are the external factors that may valorize the brand? Suggest opportunities and open innovation possibilities for improvement.

The questionnaire used in round 1 was designed to investigate all the topics selected using general questions or statements that invited respondents to express their opinions. The questionnaire also contained questions to gather general information about the panelists to provide information regarding the sample’s socio-demographic characteristics.

At the end of round 1, it was possible to summarize the answers in a set of secondary topics (characterized by the convergence of the participants’ answers) defined as “outcomes” and “development factors” (fewer than in the previous round).

The outcomes and development factors were evaluated, associated, and commented on by participants during round 2 using a second questionnaire.

Round 2 (questionnaire 2) consisted of a deeper analysis of the secondary topics and the development factors that emerged from round 1. Specifically, the aim was to discuss in depth the findings from round 1 and at the same time highlight concordance/discordance among the opinions.

For round 2, the questionnaire was closed-ended. Outcomes from round 1 were presented in the form of statements, and participants were asked to score them based on their perceived importance, using a five-point Likert-type scale (with an additional option of “undecided/cannot say”). In this survey, transitions were also analyzed using the de Loë method [

21,

60], which enables measuring consensus on a scale between “none” and “high,” depending on how the responses are spread across the categories (highly unlikely, unlikely, likely, or highly likely), taking into account that there are contiguous categories (i.e., highly likely and likely or unlikely and highly unlikely). In this study, a statement was considered as having a “high” consensus score if either 100% to 75% of the valid answers were in a single category or if 100% to 80% of the valid answers were in two contiguous categories (e.g., likely and highly likely).

Table 1 shows the percentage of consensus for each level of agreement in one category or in two contiguous categories that were considered in this study.

It was also extremely important that the closed-ended answers be accompanied by comments or explanations. After having scored each variable, respondents had to explain the reasoning behind their score (open answer), possibly with reference to relevant supporting evidence. In this way, the survey captured the diversity of expectations among respondents and enabled us to understand the reasons and contingencies underlying these differences. In addition, during round 2, participants had to relate each outcome to one of the proposed types of development factors.

Further, during round 2, respondents were also asked to cluster the outcomes based on the four “categories” of items defined as:

- ○

forecasts (participants were provided with a statistic or estimate of a future event);

- ○

issues (in terms of their importance compared to each other);

- ○

options (regarding the likelihood that specific options could be a feasible policy goal); and

- ○

goals (opinions regarding the desirability of certain policy goals).

Finally, participants were asked to judge the reliability, importance, feasibility, and desirability, respectively, of the forecasts, issues, options, and goals of the outcomes from round 1 by assigning a score to the outcomes clustered in these four categories of items, again using a five-point Likert-type scale. The scores assigned were elaborated using descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated.

Data processing was carried out in order to obtain optimal results using the SPSS v.21 statistical software package for the quantitative data. The NVivo v.11 qualitative data analysis software package was used to help in analyzing the qualitative data (e.g., words, topics, etc.) and highlight the secondary topics and the development factors (from the answers that emerged during round 1) [

61].

4. Results

Following the literature on the PD method, the process ended once iterations were judged to have stabilized and the process had reached saturation, which, in this case, occurred after round 2. Therefore, round 2 was the last significant round considered.

4.1. Round 1

Table 2 shows the sample distribution in both rounds 1 and 2 with regard to the main socio-demographic information retrieved during round 1.

In round 1, 47% of respondents were female and 53% male; this balance remained similar in round 2 (42% female; 58% male). Similarly, the balance among the age ranges was maintained during the two rounds. Most of respondents were winemakers (44% in round 1; 31% in round 2). Another large category was that of wine experts (22% in round 1; 26% in round 2), comprising wine journalists, wine influencers/bloggers, wine marketing experts, distributors, etc. Three other important categories were those of oenologists/sommeliers (22% in round 1; 26% in round 2), researchers (11% in round 2; 13% in round 2), and local entrepreneurs in the tourist and agro-food sector of importance for that territory (9% in round 1; 12% in round 2). The category of policy-makers and local administrators ranged from around 3% in round 1 to 5% in round 2. Overall, these percentages appear consistent with the objective of the study.

The first round of analysis highlighted respondents’ initial opinion concerning the brand–land link, therefore revealing respondents’ general opinion for each topic.

Regarding the questions for Topic 1 (What is the meaning of the brand–land link? What elements may contribute to valorizing the brand–land link for Etna Rosso DOC wine and the Etna valley?), below are some comments best summarizing (i.e., the most frequent statements emerging from the questionnaire) the interviewees’ opinions regarding the brand–land link for Etna Rosso DOC wine and its territory.

“[…] the link with the territory has a very significant influence on the production of Etna Rosso DOC wines, the very close link between the terroir and the wine, in fact, is strong and is perceived in all the red wines produced by the various wineries.” (Winemaker)

“[…] my profession has always been linked to ‘witchcraft,’ but it all starts with the land and the vineyard; over the years, the wine entrepreneurs of this area have changed their production strategies, passing from an approach in which quantity was given importance, to the detriment of quality, to an exactly opposite one: today, we are finally oriented to producing along the lines of ‘less is better.” (Winemaker)

“[…] for the success of the product and consequently of the company, the quality of the product, the privileged relationships with customers, and the strength of the brand are very important.” (Winemaker)

“[…] it is the terroir that ‘constitutes’ the wine.” (Winemaker)

“[…] the costs incurred to produce and market the wine would not be repaid by low selling prices.” (Winemaker)

“[…] wine is a drink that must be consumed in a convivial social occasion, conversing, having fun while enjoying oneself….” (Sommelier)

“[…] in order to appreciate a particular wine it must be known, a unique wine’s story needs to be told, the consumer must be informed about its history, from the territory to the bottle.….” (Sommelier)

“[…] the communications of the agri-food sector have leveraged its inseparable (and sometimes unconscious) link with tourism, using advertising campaigns that justify the link between the qualitative and organoleptic uniqueness of a product with its roots in its place of origin, and therefore directly or implicitly inviting the consumer-taster to become a virtual or real traveler in the production terroirs.” (Entrepreneur in the tourism sector).

“[…] in a context that is traditionally characterized by a strong wine–land identity, the primary purpose of the brand–land link has to be recognizable in the eyes of consumers/tourists in order to stand out from competitors.” (Entrepreneur in the tourism sector).

“[…] in a strategy for enhancing the product and its link with the territory, typicality should be understood as a ‘common good’ for these organizations (companies, consortia, local authorities, non-profit companies), which tend to share values, spreading their knowledge.” (Expert in territorial marketing).

“[…] it is necessary to be able to activate a path that, starting from the land–brand relationship, defines the content of the entrepreneurial strategies, generating value along three dimensions: product; territorial; and experiential.” (Expert in territorial marketing)

“[…] communicating wine means communicating the product as a whole, its history, its identity, what factors have characterized it since the vineyard; in this way, the sensory characteristics will be understood by consumers because they are contextualized in the elements (territory, vineyard, winery, winemaker) that created it. An iconic wine deserves more than any other to be related to its territory of origin, and thanks to storytelling via social networks such as Instagram, it is now possible to do this. Consumers love to identify with wine influencers and experience the story and context they tell. Winemakers should make more use of this opportunity. A wine presented in a coherent context is much more appreciated.” (Wine influencer)

“[…] tradition is important, but we cannot put aside innovation, which also supports the conservation of agricultural land biodiversity, for the competitiveness of wine entrepreneurs.” (Researcher)

“[…] a region, a territory, is perceived outside through the excellent products it produces, such as, in this case, quality wines.” (Local politician)

Regarding the questions for Topics 2 and 3 (Topic 2: What are deficiencies of the territory and how can the territorial development be organized to valorize the link between brand (Etna Rosso DOC) and land (Etna valley)?; and Topic 3: What are the economic impacts of the brand–land link for the winemakers and for the development of the territory? What are the development factors for winemakers and the territory? Provide possible solutions.), respondents highlighted many deficiencies of the Etna valley territories regarding the inability of stakeholders to unite in working toward the common goal of enhancing the brand–land link for all products from the Etnean territory, and for wine in particular.

The economic impacts of the brand–land link for the winemakers and for the development of the territory is considered a positive element in increasing competitiveness. In fact, respondents often provided examples of similar wine regions where collaboration among all stakeholders has made it possible to achieve the common objective of enhancing the value of the area and its products and making them known to consumers [

8,

10,

13,

14,

15,

19,

61,

62,

63]. An important element was the inability to make consumers/users aware of the territory and the product in order to increase their willingness to pay a higher price.

With regard to Topics 4–6, respondents provided many comments and ideas regarding exploiting the link between the wine and the territory. All the answers were analyzed and summarized using NVivo software and, at the end of the process, 12 secondary items were discovered. Among the suggestions (Topic 4), panelists highlighted the need to activate a path that defines new content in wine makers’ strategies to allow consumers to perceive the brand–land link as a mark of quality. In the same way that a region’s terroir provides local distinctive characteristics to its wine, the unique combination of the cultural and natural environment provides each wine region with its own distinctive character, which has to be valorized [

62].

Moreover, regarding the main motivations for effectively communicating the link between a wine and its territory of origin (Topic 5), food and wine tourism and experiential activities were considered crucial in the case of Etna Rosso DOC wine. Therefore, focusing on HoReCa (hotel, restaurant, and cafe) companies, consumption places, and artistic spaces in which events are organized (with the aim of facilitating the interpretation and knowledge of the wine and the territory (restaurants, wine bars, museums and festivals, events, courses, workshops, farmers’ markets, etc.)) was considered extremely important [

63]. The focus then shifted to the points of sale, accommodation facilities, services, and all the players in the tourist offer of the destination [

64], which should be improved significantly.

Opportunities (Topic 6) included using wine influencers as a source of open innovation available to wineries [

10,

61] and partnerships with hotels and restaurants or wine bars, where salespeople have the opportunity to propose and present wine to the customer [

63,

64] and improve relations with partners in the HoReCa channel.

Regarding the integration of the product with the territory, respondents highlighted various initiatives that contribute to valorizing the link between the brand (Etna Rosso DOC) and the land. Meetings comprising experts were considered effective in defining and designing concrete activities to undertake in order to enhance the product. Of particularly interest were meetings with players representing the supply chain in the wine sector (to analyze the supply chain to identify the most appropriate marketing channels) and meetings between winemakers and local politicians/representatives of public institutions (e.g., in the tourist, agro-food, and academic sectors). Also highlighted were collaborations and projects with research institutes focusing on technological transfer or training, tastings and product presentations at specific points of sale (e.g., HoReCa), and participation in collective promotional events and fairs (e.g., Vinitaly).

In summary, the most important element that emerged from all the stakeholders with different points of view can be summed up in one word, namely, “experience.” The experience of the product in a context that evokes its real origin territory [

65] was considered crucial to involve consumers and make them aware of the tangible and intangible value of Etna Rosso DOC wine [

66]. In addition, communication through wineries’ web sites and other social media channels emerged as extremely important.

Following the PD methodology, respondents expressed their opinion without interaction with each other (only with the researchers). From round 1, various outcomes and development factors emerged. These findings were discussed and analyzed in round 2.

4.2. Round 2

Round 2 comprised three steps. Initially (first step), participants had to indicate what outcomes they considered the most relevant for valorizing the territory and Etna Rosso DOC wine, as well as the importance of communication and ideas. All the outcomes were shown to respondents in the questionnaire and they could select more than one. Therefore, a percentage was obtained that expressed the measure of the respondents’ preference for each factor, given by the ratio of the number of preferences for each factor to the total number of respondents.

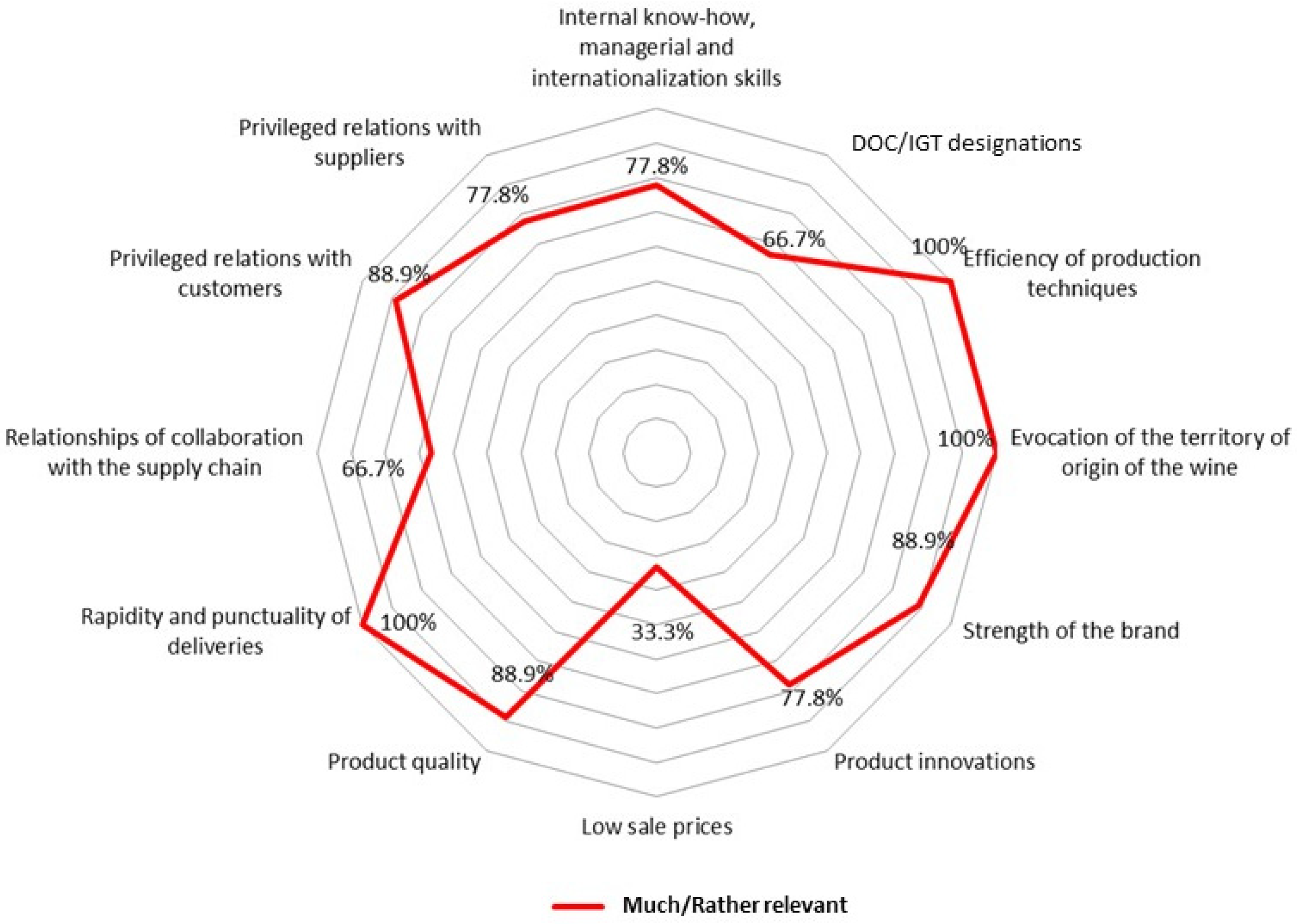

Figure 2 shows these different percentages for the 12 secondary topics (outcomes) that emerged from round 1. Three outcomes were the most important for the success of the product (100% consensus/selection by the interviewees): efficiency of production techniques; evocation of the territory of origin of the wine; and rapidity and punctuality of deliveries. Another important consideration is the fact that respondents asserted that, for the success of the product, and consequently of the company, product quality and privileged relationships with customers are crucial (reflected in 88.9% of preferences). The notion of privileged relations with consumers and customers in general relates to the importance of creating relationships and interactions to explain the product and receive feedback. Moreover, this relationship was considered to help increase brand loyalty, willingness to pay, and the strength of the brand (88.9%). It should be noted here that the winemakers of the Etna valley sell the wine with their own brand rather than under the unique brand name of “Etna Rosso DOC.”

Other elements considered relatively important (77.7% consensus) for enhancing the value of the link between Etna Rosso DOC wine and the territory were: internal know-how (77.8%); product innovations (77.8%); privileged relationships with suppliers (77.8%); and internal know-how, managerial and internationalization skills (77.8%). Lower importance was found for DOC and IGT designations (66.7%) and collaborative relationships with the supply chain operators (66.7%). Nevertheless, opinions converged regarding the criticality of efficient collaborations among the supply-chain players. Moreover, the EU quality certification (DOP) for Etna Rosso DOC wine was considered useful in helping consumers recognize the quality and the brand–land link, although the process for obtaining it was considered expensive, highly bureaucratic, and long.

Finally, low sales price was not considered advantageous by most respondents; in fact, this was selected rarely (only 33.3% of preferences). According to the panelists, the high costs incurred in producing (cultivation, harvesting, and transformation) and marketing the wine would not be covered by lower selling prices.

During the second step of round 2, respondents were asked to associate (in the questionnaire) each of the 12 outcomes/secondary topics derived from round 1 with one or more types of development factors (which also emerged during round 1), based on their personal opinion/experience (

Table 3). The respondents were able to return to their evaluations and review the results before making a final evaluation.

Table 3 shows the outcomes discovered during round 1 based on iterations and feedback from panelists when discussing Topic 1. Moreover,

Table 3 shows the association made by participants among each outcome and one or more types of development factor derived/highlighted from the panelists’ opinions during round 1 and categorized by the authors with the help of NVivo software.

Subsequently, the participants were asked to select, among the eight types of factors highlighted in round 1, those that they considered the most important to valorize the brand–land link. Additionally, in this case (as for the outcomes), all the factor types shown in the questionnaire could be selected by respondents; therefore, a percentage was obtained that expressed the measure of respondents’ preferences for each factor (number of preferences for each factor/total respondents).

Figure 3 shows the different percentages regarding the importance of the eight factors according to the panel. The greatest consensus was obtained for the following variables: competitiveness (100%); effect of the country of origin (i.e., the ability of the brand to evoke the territory) (100%); historical-artistic heritage of the territory (100%); and wine tasting (100%). These were followed by: communication from the producer of the wine peculiarities (88.9%); communication on the label (88.9%); and guided tours at wineries (88.9%). The factor that achieved the least consensus, although still considered important, was the psychological involvement of the country of origin (77.8%).

These results highlight the fact that, according to the panelists, an Etnean winery’s competitiveness is related to the identity-based link between the brand and its territory, with the COE being indicated as crucial (see

Section 1.2). This finding demonstrates that stakeholders are aware of the brand–land link.

Moreover, stakeholders considered the historical/artistic heritage of their territory to be fundamental, as well as wine tastings, in terms of valorizing the brand–land link. This finding triggers reflections on the importance for winemakers of enabling the consumer to experience the product and its territory with the aim of positioning Etna Rosso DOC as a unique wine which is not replaceable by competing products, thereby increasing consumers’ willingness to pay a premium price. To achieve this, visiting the territory and tasting the product at wineries may help consumers to have a psychological involvement, feel positive emotions, and preserve memories of them and of the knowledge gained (information) about the wine, wineries, and the territory. These are all elements that favor purchasing intentions and new consumption occasions [

2,

8,

10,

13,

15,

22,

23,

25,

27,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]. All these elements may also add value to the product/brand and increase the willingness to pay a high to medium price for Etna Rosso DOC wine. The best tools to communicate the brand and the relationship with the Sicilian territory observed are, according to the interviewees, tastings (at fairs and exhibitions) and visits to wineries. In fact, one of the experts (entrepreneurs) affirmed that “a territory and its link with wine and consequently with its brand cannot be communicated if the consumer does not experience this first-hand”.

Finally, in the third step, participants were asked to cluster the outcomes into four categories of items proposed: forecasts/reliability; issues/importance; options/feasibility; goals/desirability.

Table 4 shows the panelists’ clustering results.

After the clustering process, panelists were required to give a score using a five-point Likert scale for the 12 outcomes according to the perceived level of reliability, importance, feasibility, or desirability. The synthesis of their evaluation is shown in

Table 5.

This is an attempt to evidence the main issues for the development of the brand–land link, the main goals in terms of valorizing Etna Rosso DOC wine, the expected reliability of some activities, and the feasibility of the various options. Based on these findings, it was possible to describe a complete scenario and suggest actions and strategies for wine producers.

The results show the lack of effective actions and strategies carried out so far to bring out the uniqueness of the wines produced in the Etna valley in order to make them a symbol of history, culture, nature, landscape, and quality, thus adding value to the product.

Specifically, “Internal know-how, managerial and internationalization skills” was considered extremely reliable, followed by “Strength of the brand”. However, “Product innovations”, “Privileged relations with customers”, and “Evocation of the territory of origin of the wine” were considered likely (33%, 77%, and 62%, respectively) or unlikely (46%, 23%, and 28%, respectively). Moreover, the most important element of strength was the “DOC/IGT designation” (18% very important and 10% important), followed by “Efficiency of production techniques.” The results for “Low sales prices” were not significant. In addition, the desirable goals were, unsurprisingly, “Product quality” (95% very desirable), “Rapidity and punctuality of delivers” (80% very desirable), and “Relations with partners in the supply chain” (85% very desirable). These results highlight that strategies to reach consumers must be developed through the realization of these objectives and based on the reliability of the emerging actions.

However, the communication and the experience of the product and land is clearly currently lacking.

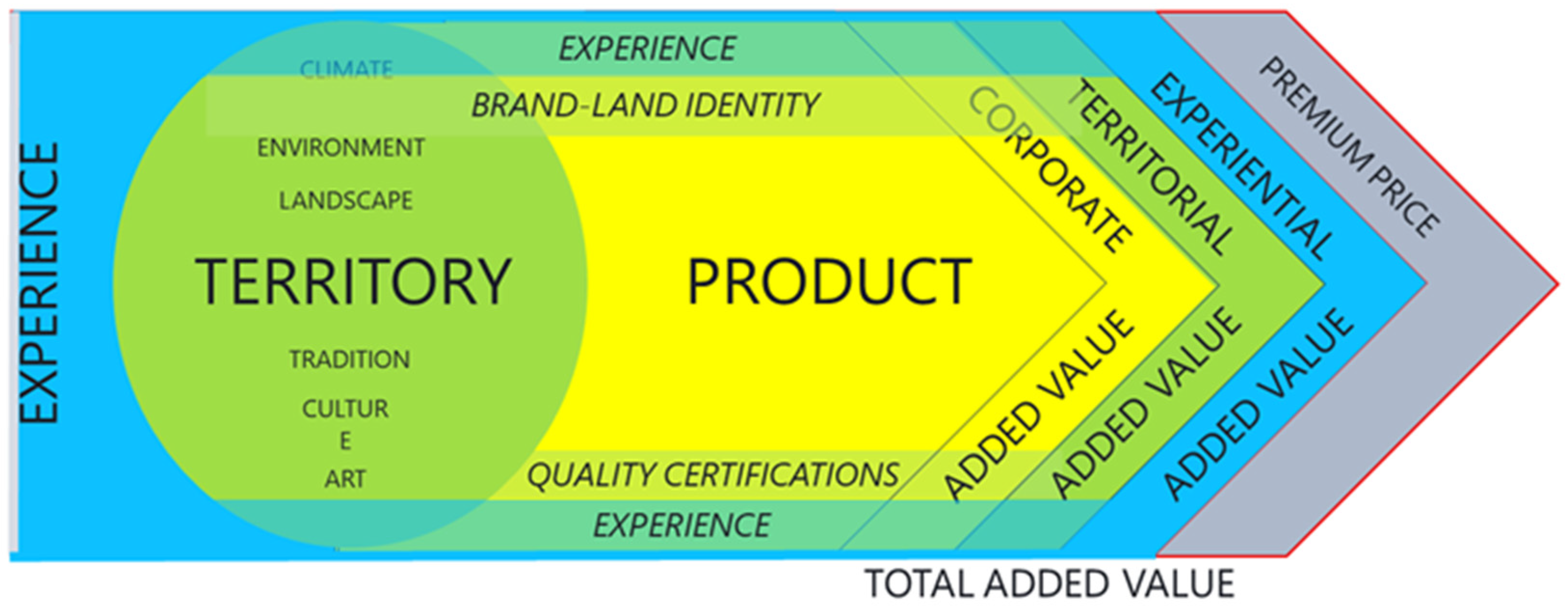

To conclude the presentation of the results, it may be helpful to show the process of value creation in order to propose a new model thereof which is adapted to the context of wines with a strong brand–land identity and a high value of the territory, thus enabling the generalization of the results to similar wine contexts and regions.

Figure 4 graphically depicts the synthesis of all the results, revealing how the experience of territory and product is the key element to convey the values of the territory (encompassing climate, environment, landscape, tradition, culture, and art) and the value of product (comprising intrinsic qualities and firm qualities) to the customer. This model wants to show how, experience is the key factor for consumers to understand the added value of Etna Rosso DOC wine and increase the willingness to pay for it, accepting to pay a “premium price”.

Specifically,

Figure 4 shows relationships among three dimensions: (1) corporate and product added value (or margin); (2) territorial added value; and (3) the added value of the experience of the territory and product. All these dimensions produce added value; therefore, the total added value of Etna Rosso DOC wine is the sum of the three added values “plus” a premium price given by knowledgeable consumers. The first dimension is internal, and consists of value emanating from the cultivation, harvesting, transformation/production and sale phases, according to the Porter’s value-chain model, i.e., the primary activities (inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, service) and the supporting activities (firm infrastructure, human resource management, technology development, procurement) that produce a margin, i.e., added value. The second dimension is the territory, which is external to the firms but highly influential for Etna Rosso DOC wine because it characterizes it and distinguishes it from any other wine. The third dimension is also external, representing the final consumer’s experience of the wine and the territory (the Etna valley), which originates and characterizes the wine.

The brand is a crucial element to position the wines in the market. Nevertheless, in this case, the firm’s assets comprise not only tangible and intangible internal elements but also intangible external elements that may influence the consumers’ purchasing intentions whether this consumer is aware and understands the value of these elements.

5. Discussion

As shown in

Section 4, all the objectives of the study were achieved. The shareholders are aware of the strong relationship between brands and the territory/place of production of quality wines. The elements that compose this relationship were identified as outcomes and development factors. Moreover, these elements were measured in order to assess the current situation regarding the effectiveness of brand–land links in terms of the valorization of Etna Rosso DOC wine. Solutions were suggested and analyzed in terms of reliability, importance, feasibility, and desirability.

The results show that the formulation of an effective integrated territorial marketing strategy is considered necessary to valorize Etna Rosso DOC wine using its link with the Etnean land. The elements to be considered that emerged from the PD interviews led all stakeholders (e.g., companies, consortia, local authorities, non-profit companies, etc.) to reconsider the territory as a “common good” [

43]. From the outcomes of the PD round 1, it emerged that consultation panels comprising expert stakeholders from all sectors involved are an effective tool, in line with previous literature [

67]. All these stakeholders together (local politicians, winemakers, tourist entrepreneurs, researchers, etc.) have in common the interest to enhance and valorize both the territory (as a product and as an ecosystem service) and the typical local food products of high quality, including Etna Rosso DOC wine. This mission would require integrated work between wine entrepreneurs and local governments [

67].

All panelists stated the importance of users’/tourists’/wine consumers’ “experience” in order to understand the identity bond between Etna Rosso DOC wine and the Etna valley (land of origin). In fact, in the absence of correct information, the final consumer has only the price on which to make purchasing choices. The results highlighted that positioning Etna Rosso DOC wine with a lower price is not a feasible strategy because it would not allow covering the higher cost of production.

Additionally, this study has highlighted that, in the wine firm value chain, the territory (in most cases, and particularly in this case), with its naturalistic, landscape, historical, and cultural heritage, becomes another element that adds value to wine [

68,

69]. However, the territory has to be communicated through a path of experience, via which Etna Rosso DOC wine may become the symbol of this territory and the means of getting to know it. In this sense, the emotional-experiential dimension is of particular relevance. Therefore, in line with prior studies, stakeholders highlighted the need to let consumers experience the territory and the product, possibly in the real context, and hopefully in a coherent context [

63].

Moreover, the study provided a new visual representation of this model of value creation adapted to the context of wines with a strong brand–land identity and a high value of the territory, thus enabling the generalization of the results to similar wine contexts and regions. This model, therefore, is not intended to overturn previous scientific findings regarding the added value that a territory or experience imparts to a wine [

70,

71]; rather, it confirms them. In addition, however, it provides a visual summary that highlights, for the first time, the main elements that contribute to the value generation process and the order in which these elements do so. In other words, the model shows how additional value is generated over and above that generated by the mere business activity (explained by the Porter’s value-chain).

This model may include all those wines that have the same characteristics as Etna DOC wine, i.e., wines produced in extreme territories or where heroic viticulture is practiced, wines with strong identity connotations and strong ties to the territory (a territory that provides the wines with characteristics of uniqueness and distinctiveness, but, at the same time, that causes extreme difficulty for producers given the extreme characteristics of the grape growing area).

The model presented here has the merit of providing a synthesis that can be easily understood visually by scholars in the field. In particular, it shows, represented by different colors, the elements that generate value, and their connection, in order: (1) product; (2) territory; and (3) experience. It also shows the passage of value through the colors and the order in which these elements provide added value to the product. First, the company’s added value is formed, i.e., product-brand value that comes from the company’s internal activity. This value is that represented by Porter’s value chain. Next, for wines with brand–land identity, to this value can be added a second value, namely that conferred by the territory of origin (which gives the wine its inimitable traits of uniqueness and quality). This value is in addition to the first margin produced by the business activity, in line with previous literature [

72]. Additionally, there is a third value factor: experience. To confer value, this experience must be linked by users both to the land and the wine. This observation applies the findings in the literature to the wine experience [

73]. It is only through experience, in fact, that consumers will be able to understand both the value of the territory of origin and the value that this territory confers on the wine by shaping it. Thus, the model shows how experience, indicated by the color blue, must contain within it both the territory and the product. Only in this way can it bestow additional added value upon wine that will be understood by the consumer. The territory, in turn, must also “include,” and therefore “contain” the wine that is generated within it.

Therefore, this model, presented here for the first time in the wine marketing literature, is intended to visually show what has been demonstrated previously (by previous studies on various food products and particularly those on wine and the brand–land link), namely the following statements that constitute the results of the study and meet the stated objectives: (1) all territories provide added value to wines, (2) the higher the value of the territory of origin, the higher the value conferred by the territory on the wine; (3) a wine with high identity characteristics and strong ties to the territory of origin acquires an additional margin of value conferred on it by the territory; and (4) the experience of the territory and the wine is crucial because, on the one hand, it assigns an additional margin of value to the wine and also allows consumers to “accept” a higher premium price, since they are aware of the reasons for the higher price.

This last point is based on the existing literature on the value of territories, but also on what the characteristics are that give value to a territory (discussed extensively in

Section 2). Therefore, a territory of very high value in terms of landscape, environmental, cultural, historical, and social values, such as that of Etna, can only provide ecosystem services and further value to the wine generated in it [

74,

75].

To summarize, three key points emerge. First, the value-generating process conferred by the company (Porter’s value chain) through the primary activities (inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, service) and supporting activities (firm infrastructure, human resource management, technology development, procurement) produce a margin, i.e., added value. Second, the contribution of intrinsic value to the product by the territory in which the wine-producing firm is also located generates further added value. Finally, the process of consumers/visitors gaining awareness of the territory and the product, i.e., “experience”, in turn produces further added value. However, while the corporate margin or value added contributes to generate the price at which the entrepreneur places a product on the market, taking into account the costs and value of the corporate brand name, the “territorial and experiential margin” or value added represent an additional premium.

Therefore, the study reveals that there is an additional “premium price” that the consumer is willing to pay for a quality wine with a high brand-land link only if he or she recognizes it in the wine as an additional “extra value”.

This model is an important theoretical finding that synthesizes, describes and corroborates the results of previous similar studies and provides a new basis for future confirmatory or disproving studies. Moreover, the model-built basing on the theory of Michael Porter’s value chain-forms bridges between design and business decision making—in operations, in support functions, and in the development of long-term strategies by winemakers [

76]. Results suggest that a reorganization in the current value chain of the company would be required, in line with Koc and Bozdag (2017) [

77]. Moreover, the integration of internal supply chain with territories is also necessary, confirming findings of Ros-Tonen et al. [

78,

79].

The use of experience of product/brand and territory through the direct involvement of the user/consumer by winemakers and stakeholders guarantee the uniqueness of the offer, which inevitably becomes personal and irreplicable in another context [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. These results highlight that currently, only limited information is conveyed to consumers, and only at a few consumption places, such as local hotels and restaurants. However, effective communication to users and consumers was considered crucial to communicate the added value of the product (deriving from the brand–land link) and the superior sensorial qualities. Nevertheless, results shows that effective communication strategies do not currently exist at a territorial level or even at a private (entrepreneurial) level.

The outcomes of this study suggest the need to refine firms’ current communication strategies. Moreover, these results provide food for thought concerning effective communication tactics that can be adopted by all actors in the Etna territory. In particular, in line with prior studies, institutional communication aimed at enhancing and promoting the territory as a whole, i.e., taking into account material and immaterial elements, was considered crucial [

80]. Communication today cannot ignore the significant changes that have occurred in recent years in the ways and means utilized by companies for communication purposes. It would therefore be interesting to consider the importance of social networks and the emergence of prominent figures such as social influencers [

81,

82]. In fact, considering the increasing importance of wine influencers in the wine sector, the use of wine influencers could help to “tell the story” of the wine effectively, through storytelling (communicating their personal experiences using videos and images), providing information generated by the influencer himself/herself, and the additional interaction between the followers [

10,

63]. Such “consumer-generated information” emphasizes the evolution of the democratization of the brand by users who talk about it after having experienced it (as opposed to information provided by the producers), which is the new “word of mouth” formula [

10,

63]. Communication strategies that also encompass the “creation” and “use” of communities of users united by common interests (themes, products, lifestyles, territories, etc.) could be one of the effective tools to be implemented. Storytelling (video, images, and photos) to spread information and communicate the wine and its territorial identity are increasingly common, and the effectiveness of this type of communication has been amply demonstrated by previous studies [

10,

11,

63]. Another potentially effective tactic could concern the labels and the web sites of the producing cellars. Wine labels and web sites can both certainly be an effective means of communicating, visually, the impressive wine territory of the Etna volcano in Sicily [

20,

83].

Quality is one of the axes around which the Italian agri-food system revolves; according to some definitions, it manifests itself through the properties and characteristics of the products or services, which confer the ability and aptitude to satisfy the needs and requirements of end users. In choosing quality products, labeling is an important tool that facilitates the establishment of a relationship of mutual trust between the producer and the consumer through the description of the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of the product itself, and even more so for wine.

Regarding quality in the wine sector, this can be linked to three elements: (1) the grape production area, highlighting the link between the soil and the grapes, from which the finished product draws the qualities necessary to distinguish it from others; (2) the year of production of the wine, since this information identifies and differentiates it from products of the same kind; and (3) the company brand and/or the presence of a quality certification. Therefore, a further concrete suggestion from this study, in line with previous literature on integration of internal supply chain with territories [

78,

79], is the need for actions undertaken by national and regional institutions to protect and enhance these inimitable wines, by supporting producers in the market.

One of these type of institutions in Italy is the Consortium for the Protection of Etna DOC Wines [

84], which, similar to those described in

Section 1, has the objective of protecting, promoting, and enhancing these wines and providing information to consumers. Other entities that might provide concrete help in collaboration with the Consortium include: the Etna Wine Routes Association; the Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies; and the Central Inspectorate for the Protection of Quality and Fraud Prevention of Agri-food Products.

If territories are brands, then the typical products of a territory are brands too. Therefore, the findings of this study confirm the results of Charters et al. (2014) and other authors about the importance of integrated strategies for wine territories focusing on winemakers’ and stakeholders’ needs that involve territorial governance [

85,

86,

87,

88,

89].

6. Limitations

Only a handful of keywords (brand–land and wine territory) guided the present research, and despite the fact that the choices remain subjective, the findings, utilizing the PD methodology, highlighted a strong brand–land link between Sicilian Etna Rosso DOC wine and its territory. While contributing to the literature on the brand–land link and the Etna valley territory, the study may have weaknesses and limitations.

Some limitations may come from the chosen methodology (PD), including group size and composition, practical constraints of location and timing, and researcher and participant positions. However, numerous experiments conducted during the 1960s and 1970s have demonstrated that the application of the Delphi method is particularly suitable for those problems where the most useful information, which one hopes to derive, is the informed judgment of experienced and knowledgeable people in the relevant field, as in the case studied. In conclusion, the use of the Delphi technique, with its staged structure, is particularly appropriate when the universes or issues to be explored are uncertain in nature, and when the information we have regarding the object of research is scarce, difficult to find, or unavailable. Criticisms have also been directed at the Delphi method, the most relevant of which was levelled by Sackman [

90], who accused the Delphi technique of lacking scientific rigor, but it is not clear why it should be methodologically less valid than techniques such as interviewing, case study analysis, or life histories that are now used as tools for political investigation and analysis. Another main limitation of this method is the low involvement of all the participants invited [

91]. Concerns about the validity, usefulness, and credibility of the results achieved through the use of the Delphi method are valid and appropriate, but just as this technique is criticized, so should all other techniques based on an exchange of information be subject to the same scrutiny.

It is important to note that every effort was made to design and conduct the present research in such a way as to minimize any bias of the method, so much so that in this study, we proposed an improved and strengthened version of the method incorporating the standardization of responses after the first round and further adapted the method for agri-food and territorial marketing research.

Other limitations are related to the focus of this paper on one specific wine region in Sicily (south Italy). Certainly, linking the research on the brand–land link to a specific wine territory led us to exclude other outlooks. It is likely that structural and cultural differences could influence the results [

28,

92]. Therefore, we believe that this exploratory study can contribute to future wine marketing research investigating small, specialized wine regions of high social and economic relevance. Accordingly, this study should be replicated in other wine regions where unique and inimitable wines are produced [

28]. Therefore, the limitations of this study provide avenues for further research. Further investigations may address these limitations and explore several connected research areas. Particularly, to confirm the results, further studies using the same methodology could be carried out in other Italian or foreign wine regions where the heroic viticulture is practiced (e.g., the Alto Adige region or the Langhe, Roero, and Monferrato regions in Italy, the Wachau Region in Austria, the Douro Region in Portugal, the island of Pico in the Azores archipelago, or the Lavaux Vineyard Terraces in Switzerland).

Moreover, to complete the study, a survey of consumers on site and outside Sicily should be carried out in order to confirm the theoretical results and practical strategies to valorize the wine and the territory. In this study, we did not analyze consumers’ preferences regarding the sensorial attributes of this wine, since the objective of this study was to understand stakeholders’ points of view. Nevertheless, a sensory test should be carried out, both outside of and within a context that is appropriate for the product. In addition, a study of consumers’ awareness and the dimensions of effective communication for conveying value should be undertaken by using focus groups of visitors and consumers.

7. Conclusions