Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency, Biomass, and Sugar Content of Sweet Sorghum Under Different Water and Salt Conditions in Arid Region of Northwest China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

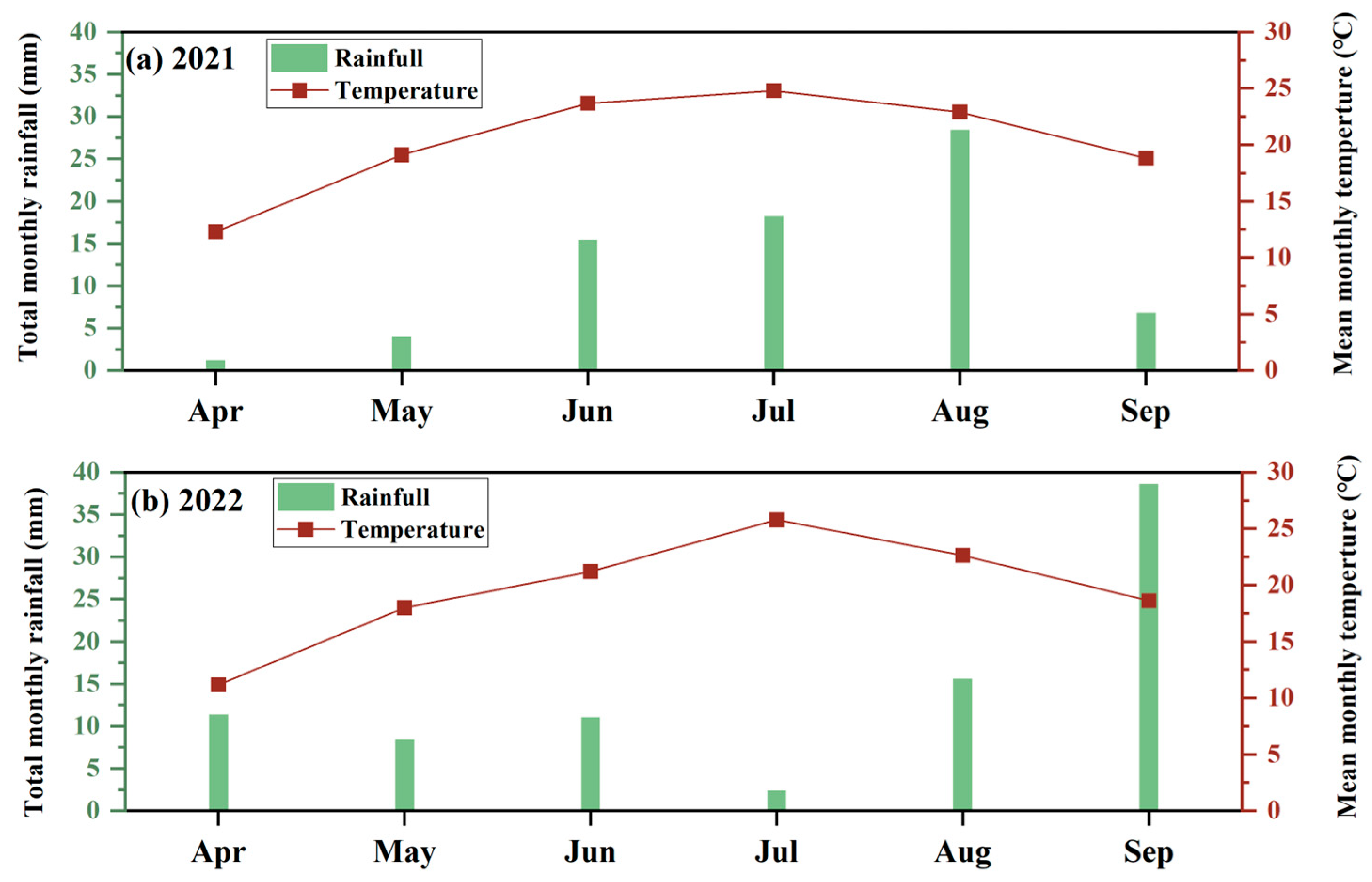

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measurement Items and Methods

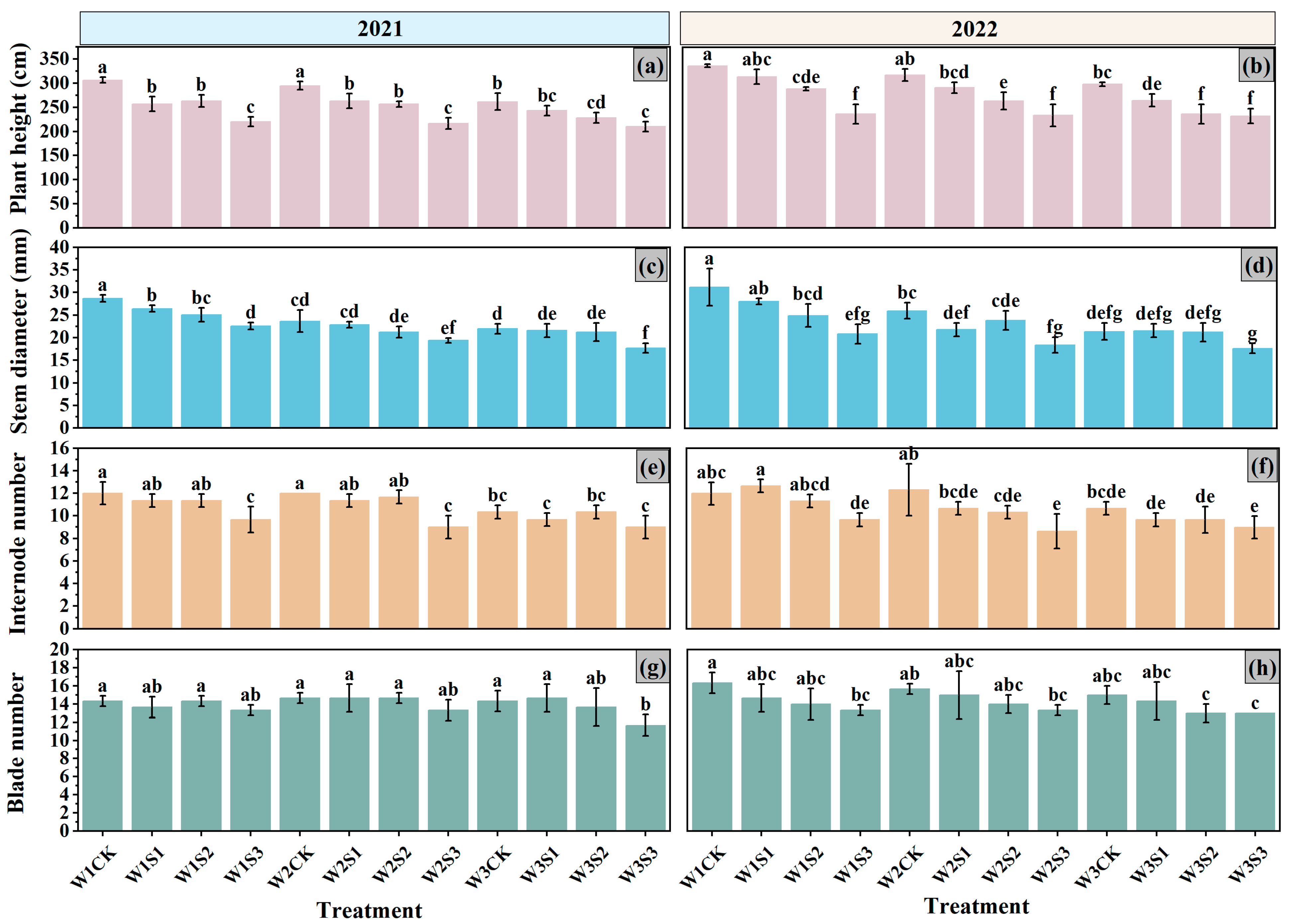

2.3.1. Growth Characteristics

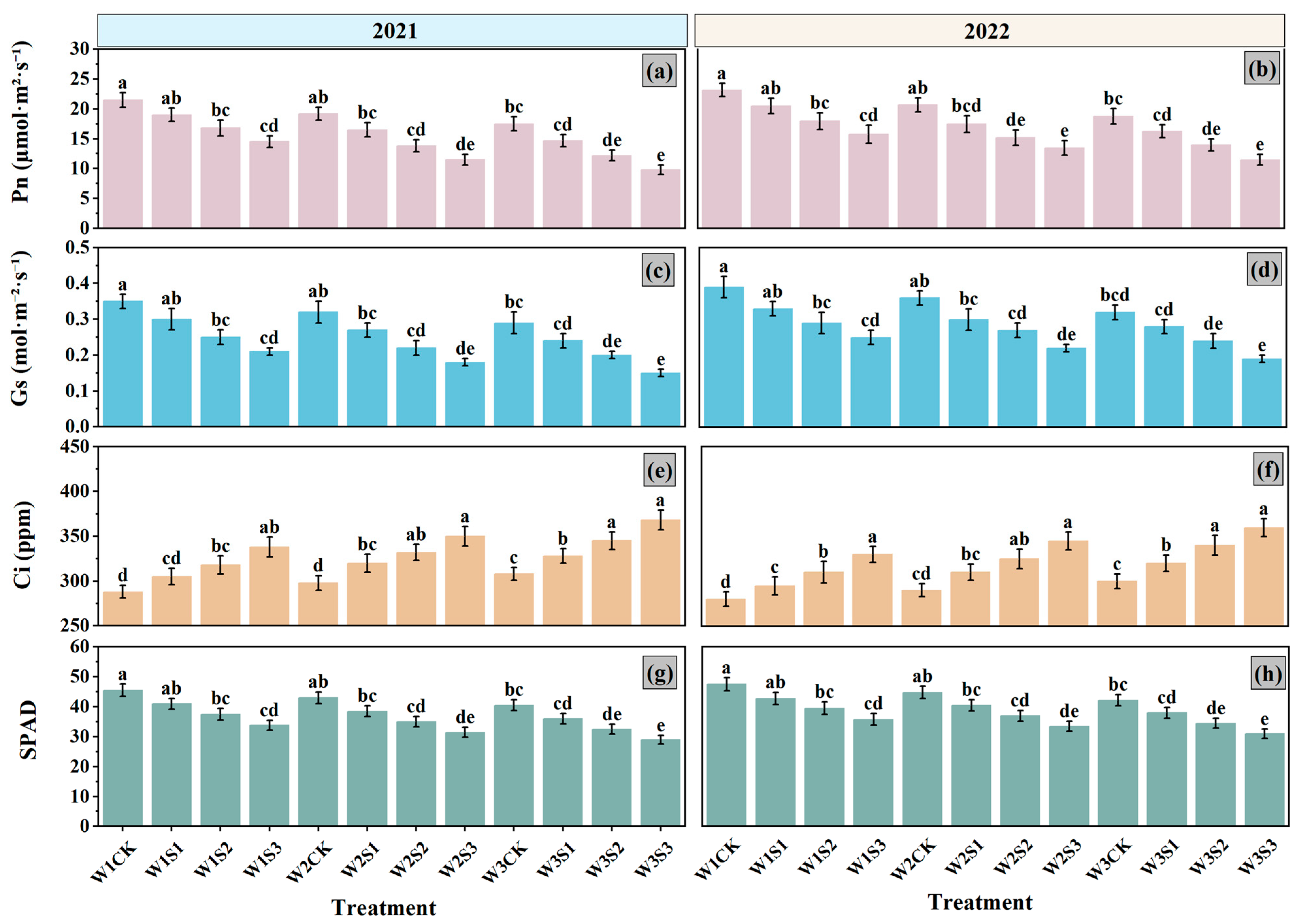

2.3.2. Photosynthetic Characteristics

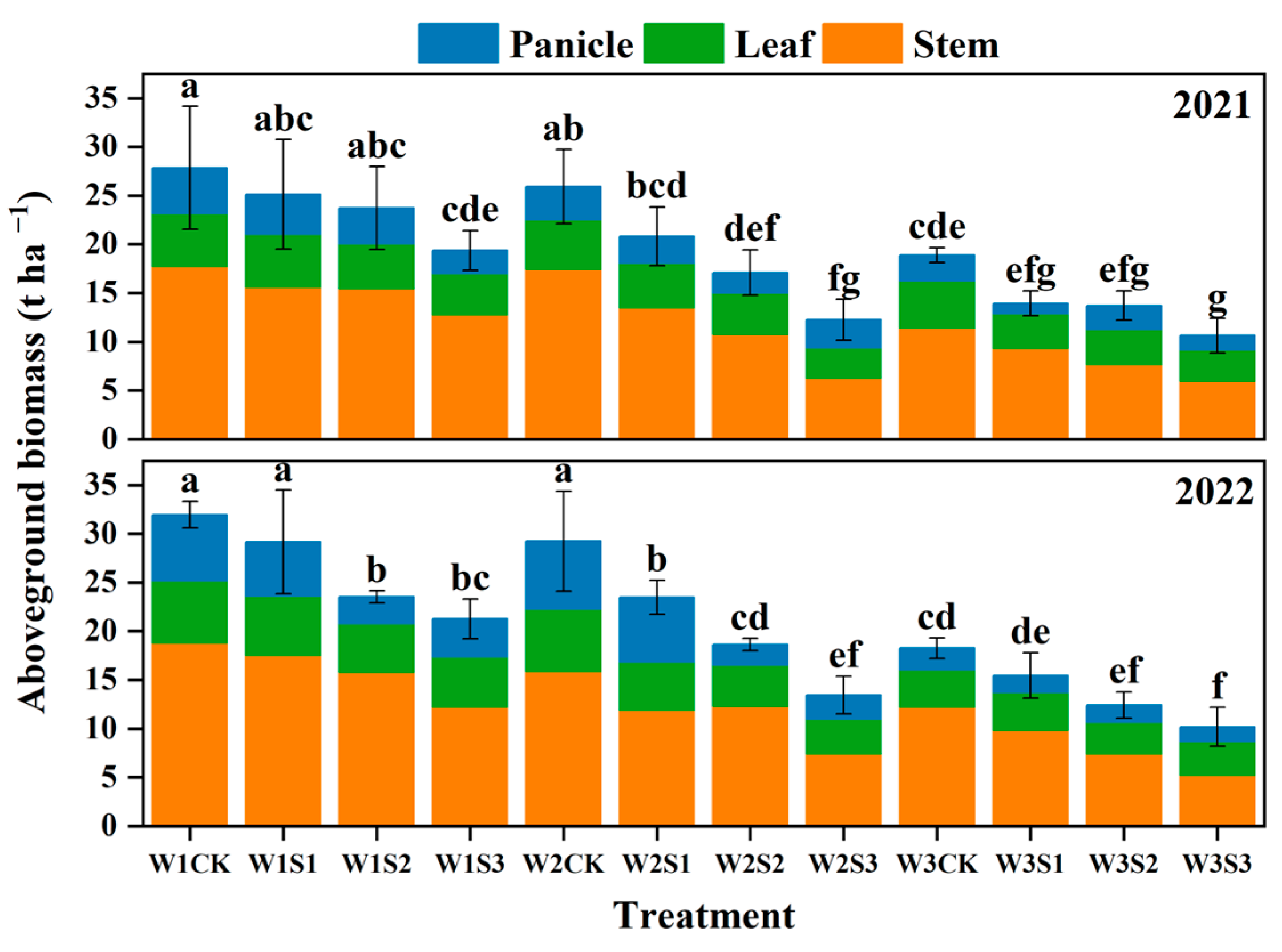

2.3.3. Biomass

2.3.4. Stem Sugar Content

2.4. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Emergence Rate

3.2. Growth Characteristics

3.3. Photosynthetic Characteristics

3.4. Aboveground Biomass

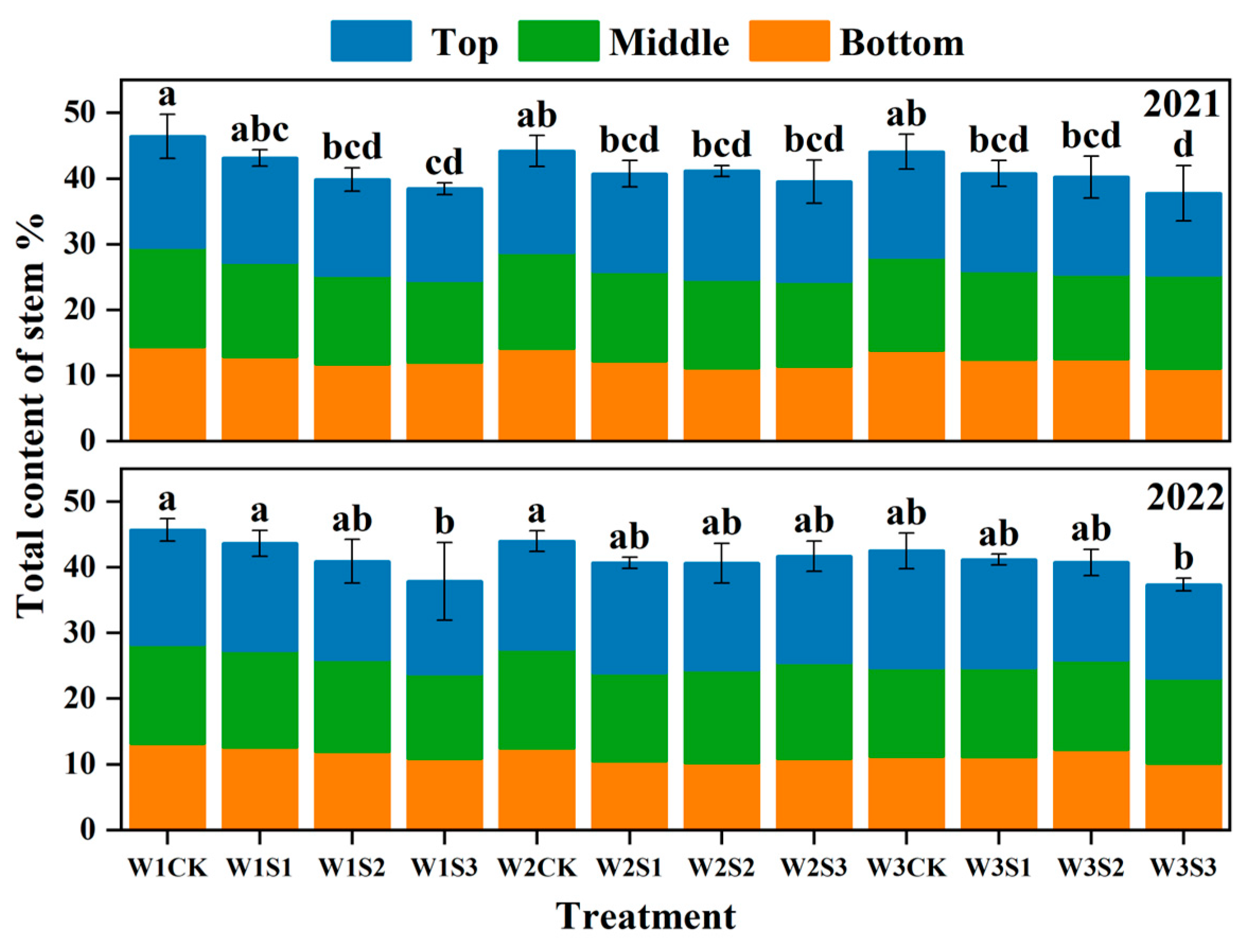

3.5. Sugar Content

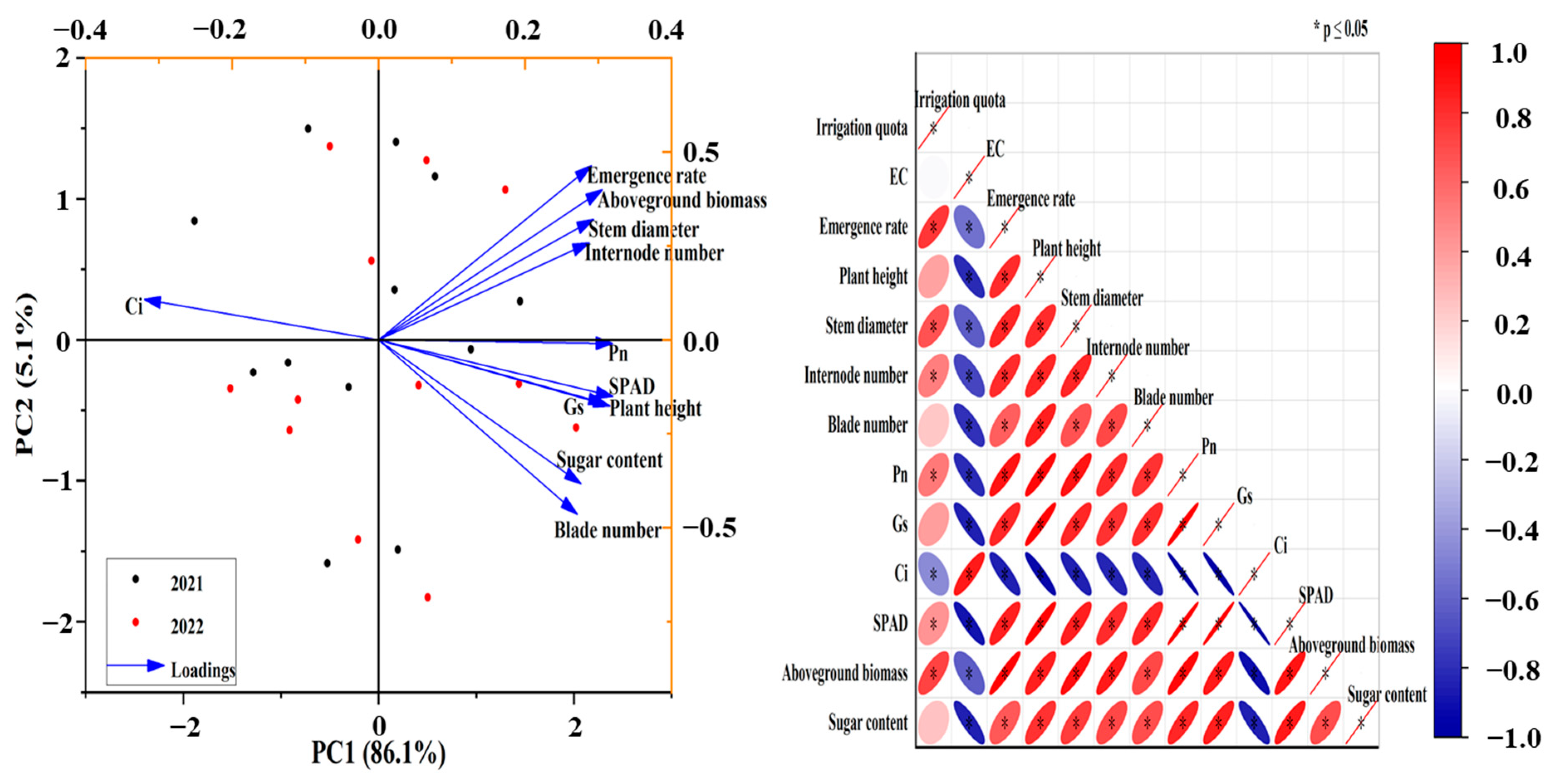

3.6. Comprehensive Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Emergence Rate and Growth Characteristics

4.2. Biomass Accumulation

4.3. Sugar Content

4.4. Photosynthetic Characteristics and Their Role in Biomass and Sugar Content Accumulation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dolan, F.; Lamontagne, J.; Link, R.; Hejazi, M.; Reed, P.; Edmonds, J. Evaluating the Economic Impact of Water Scarcity in a Changing World. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingrao, C.; Strippoli, R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water Scarcity in Agriculture: An Overview of Causes, Impacts and Approaches for Reducing the Risks. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Yin, Y. Eco-Reconstruction in Northwest China. In Water and Sustainability in Arid Regions: Bridging the Gap Between Physical and Social Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, X.; Jiang, S.; Lin, L.; An, T. Virtual Water Output Intensifies the Water Scarcity in Northwest China: Current Situation, Problem Analysis and Countermeasures. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 144276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X. Analysis of Crop Sustainability Production Potential in Northwest China: Water Resources Perspective. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, S.; Xu, X. Quantitative Review of Soil Salinization Research Trends Based on Bibliometrics. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2024, 64, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; He, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; Chen, L.; Lin, P. Soil Water and Salt Migration in Oasis Farmland during Crop Growing Season. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondoker, M.; Mandal, S.; Gurav, R.; Hwang, S. Freshwater Shortage, Salinity Increase, and Global Food Production: A Need for Sustainable Irrigation Water Desalination—A Scoping Review. Earth 2023, 4, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Luo, J.; Park, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Masin, R. Soil Salinization in Agriculture: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Combining Nature-Based Solutions and Bioengineering. iScience 2024, 27, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Umakanth, A.V.; Tonapi, V.A.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, M.K. Sweet Sorghum as Biofuel Feedstock: Recent Advances and Available Resources. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Nkansah, N.B.; Li, J.; Rooney, W.; Wang, D. A Review of Sweet Sorghum as a Viable Renewable Bioenergy Crop and Its Techno-Economic Analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lei, S.; Gong, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, Z. Field Performance of Sweet Sorghum in Salt-Affected Soils in China: A Quantitative Synthesis. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Gao, L.; Hu, W.; Gao, Q.; Yang, B.; Zhou, J. Genome-Wide Association Study Based on Plant Height and Drought-Tolerance Indices Reveals Two Candidate Drought-Tolerance Genes in Sweet Sorghum. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakoglou, I.; Dhima, K.; Karagiannidis, N.; Gatsis, T. Sweet Sorghum Productivity for Biofuels under Increased Soil Salinity and Reduced Irrigation. Field Crops Res. 2011, 120, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Ahmad, F. Sorghum: Role and Responses Under Abiotic Stress. In Sustainable Remedies for Abiotic Stress in Cereals; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Al Hinai, M.S.; Hafeez, M.B.; Rehman, A.; Wahid, A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Regulation of Photosynthesis under Salt Stress and Associated Tolerance Mechanisms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 178, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F. Insights into Plant Salt Stress Signaling and Tolerance. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.S.; Kumar, C.G.; Prakasham, R.S.; Rao, A.U.; Reddy, B.V.S. Sweet Sorghum: Breeding and Bioproducts. In Industrial Crops: Breeding for BioEnergy and Bioproducts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, T.; Fan, G.; Wang, T. Changes in Soil Properties and Accumulation of Soil Carbon After Cultivation of Desert Sandy Land in a Marginal Oasis in Hexi Corridor Region, Northwest China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2017, 50, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, B.; Si, R.; Zhao, Y. Effects of Soil Texture and Irrigation on Growth Characteristics and Water Productivity of Sweet Sorghum in the Middle Reaches of Heihe River. Soils Crops 2020, 9, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-L.; Cheng, X.; Li, G.-Y. Screening Sweet Sorghum Varieties of Salt Tolerance and Correlation Analysis among Salt Tolerance Indices in Sprout Stage. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2010, 18, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Yang, Z.; Wei, X.; Yuan, F.; Yin, S.; Wang, B. Evaluation of Salt-Tolerant Germplasm and Screening of the Salt-Tolerance Traits of Sweet Sorghum in the Germination Stage. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Reguera, E.; Veatch, J.; Gedan, K.; Tully, K.L. The Effects of Saltwater Intrusion on Germination Success of Standard and Alternative Crops. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 180, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Sghaier, A.; Tarnawa, Á.; Khaeim, H.; Kovács, G.P.; Gyuricza, C.; Kende, Z. The Effects of Temperature and Water on the Seed Germination and Seedling Development of Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plants 2022, 11, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, R.C.; Bradford, K.J.; Khanday, I. Seed Germination and Vigor: Ensuring Crop Sustainability in a Changing Climate. Heredity 2022, 128, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, C.; Bo, Y.; Song, C.; Zhu, F. Improving Crop Salt Tolerance through Soil Legacy Effects. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1396754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The Physiology of Plant Responses to Drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Maroco, J.P.; Pereira, J.S. Understanding Plant Responses to Drought—From Genes to the Whole Plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, S.; Zougmoré, R.B.; Coulibaly, A.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Tetteh, J.P. Accelerating Seed Germination and Juvenile Growth of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) to Manage Climate Variability through Hydro-Priming. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhou, G. Effects of Soil Water Stress on Maize Morphological Development and Yield. J. Ecol. 2004, 24, 1556–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H. Plant Salt Response: Perception, Signaling, and Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1053699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Liu, X.-J.; Xu, J.; Mao, R.-Z.; Wei, W.; Yang, L.-L. Effects of Nitrogen on Sweet Sorghum Seed Germination, Seedling Growth and Physiological Traits under NaCl Stress. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2013, 20, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavilli, H.; Yolcu, S.; Skorupa, M.; Aciksoz, S.B.; Asif, M. Salt and Drought Stress-Mitigating Approaches in Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) to Improve Its Performance and Yield. Planta 2023, 258, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, R.; Liu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, C. Research on Water and Fertilizer Ratio Model of Sweet Sorghum Planting in Arid Area of Northwest China. J. Irrig. Drain. 2021, 40, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Dolat, A.; Steinberger, Y.; Wang, X.; Osman, A.; Xie, G.H. Biomass Yield and Changes in Chemical Composition of Sweet Sorghum Cultivars Grown for Biofuel. Field Crops Res. 2009, 111, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks, P.S.; Kaiser, C.M.; Hawkins, E.M.; Brown, P.J. Genomewide Association for Sugar Yield in Sweet Sorghum. Crop Sci. 2015, 55, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almodares, A.; Hadi, M.; Dosti, B. The Effects of Salt Stress on Growth Parameters and Carbohydrates Contents in Sweet Sorghum. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 2, 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.N.; Ottman, M.J. Irrigation Frequency Effects on Growth and Ethanol Yield in Sweet Sorghum. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.; Chaves, M.M. Photosynthesis and Drought: Can We Make Metabolic Connections from Available Data? J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, A.; Fendel, A.; Nguyen, T.H.; Adebabay, A.; Kullik, A.S.; Benndorf, J.; Léon, J.; Naz, A.A. Natural Diversity Uncovers P5CS1 Regulation and Its Role in Drought Stress Tolerance and Yield Sustainability in Barley. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2569–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, D.W.; Tezara, W. Causes of Decreased Photosynthetic Rate and Metabolic Capacity in Water-Deficient Leaf Cells: A Critical Evaluation of Mechanisms and Integration of Processes. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Drought-Inhibition of Photosynthesis in C3 Plants: Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Limitations Revisited. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under Drought and Salt Stress: Regulation Mechanisms from Whole Plant to Cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Unraveling Salt Stress Signaling in Plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Balfagón, D.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Modulation of Antioxidant Defense System Is Associated with Combined Drought and Salinity Stress Tolerance in Citrus. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Singh, P.; Siddiqui, H.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Salinity Induced Physiological and Biochemical Changes in Plants: An Omic Approach towards Salt Stress Tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahad, S.; Bajwa, A.A.; Nazir, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Farooq, A.; Zohaib, A.; Sadia, S.; Nasim, W.; Adkins, S.; Saud, S.; et al. Crop Production under Drought and Heat Stress: Plant Responses and Management Options. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Irrigation | Salt | Emergence Rate% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | W1 | CK | 97.2 ± 3.5 a |

| S1 | 86.0 ± 3.6 b | ||

| S2 | 82.4 ± 5.6 b | ||

| S3 | 70.0 ± 7.04 c | ||

| W2 | CK | 91.6 ± 7.5 a | |

| S1 | 81.6 ± 3.9 a | ||

| S2 | 61.2 ± 12.0 b | ||

| S3 | 50.0 ± 8.9 b | ||

| W3 | CK | 64.0 ± 6.6 a | |

| S1 | 46.4 ± 5.9 b | ||

| S2 | 47.2 ± 8.5 b | ||

| S3 | 37.6 ± 7.3 b | ||

| 2022 | W1 | CK | 98.4 ± 0.02 a |

| S1 | 97.2 ± 2.0 a | ||

| S2 | 94.0 ± 3.6 a | ||

| S3 | 76.4 ± 7.5 b | ||

| W2 | CK | 94.8 ± 3.0 a | |

| S1 | 83.6 ± 2.3 b | ||

| S2 | 82.0 ± 2.8 b | ||

| S3 | 67.6 ± 4.6 c | ||

| W3 | CK | 72.0 ± 3.8 a | |

| S1 | 57.2 ± 6.1 b | ||

| S2 | 48.8 ± 6.5 b | ||

| S3 | 39.2 ± 5.9 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, W.; He, Z.; Liu, B.; Ma, D.; Si, R.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Malekian, A. Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency, Biomass, and Sugar Content of Sweet Sorghum Under Different Water and Salt Conditions in Arid Region of Northwest China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14122321

Sun W, He Z, Liu B, Ma D, Si R, Li R, Wang S, Malekian A. Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency, Biomass, and Sugar Content of Sweet Sorghum Under Different Water and Salt Conditions in Arid Region of Northwest China. Agriculture. 2024; 14(12):2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14122321

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Weihao, Zhibin He, Bing Liu, Dengke Ma, Rui Si, Rui Li, Shuai Wang, and Arash Malekian. 2024. "Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency, Biomass, and Sugar Content of Sweet Sorghum Under Different Water and Salt Conditions in Arid Region of Northwest China" Agriculture 14, no. 12: 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14122321

APA StyleSun, W., He, Z., Liu, B., Ma, D., Si, R., Li, R., Wang, S., & Malekian, A. (2024). Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency, Biomass, and Sugar Content of Sweet Sorghum Under Different Water and Salt Conditions in Arid Region of Northwest China. Agriculture, 14(12), 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14122321