Abstract

The rapid increase in the global human population, particularly in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs), causes severe food shortages. Food shortages are complex and can be linked to economic, environmental, social, and political variables. Harnessing village chicken products serves as a cheap commercial chicken substitute to address food shortages. The consumption and sales of protein products from village chickens, such as meat, eggs, and internal organs, ensures food security and poverty alleviation in limited-resource communities. However, village chickens have poor-quality end products due to poor management and animal-rearing resources. Village chicken production challenges include the absence of high-quality feed, biosecurity, recordkeeping, housing, and commercial marketing of its end products. Management being based on cultural gender roles instead of the possession of formal poultry management training further limits village chicken production. To improve village chicken end-product quality, poultry management trainings for rural women are suggested due to studies showing that women mainly manage village chicken production. Furthermore, to create a formal market share of village chickens, sensory evaluations need to be conducted using mainstream poultry consumers. This review examined the potential contribution of village chickens in achieving Sustainable Development Goals—one, No Poverty and two, Zero Hunger—to benefit vulnerable groups in resource-poor communities.

1. Introduction

Globally, the family poultry sector is divided into small extensive scavenging, extensive scavenging, semi-intensified, and small-scale intensified, with the common objective of maximizing production [1]. In developing countries, approximately 475 million farmers rear village chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus), and the production depends on less than 2 hectares of land [2]. In these countries, village chickens are widely spread in rural, peri-urban, and urban regions [3]. For centuries, farmers have been reliant on village chickens for survival in resource-poor communities [4]. In addition, the FAO [5] has indicated that various food production systems and agricultural practices are required for the 2023 implementation plan to satisfy human needs for the present and the future. Furthermore, the Sustainable Development Goal Policy 2030 plan, mainly number 2 (Zero Hunger), requires an urgent and concerted plan for food security and sustainable agriculture, especially in developing countries [6].

Developing strategies to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals that address food security and rural development, including underutilized products and their gaps for sustainable agriculture, is encouraged [7]. As recommended by numerous authors, there is great potential in using village chickens reared under backyard production systems for consumption and income generation, especially for vulnerable groups. Village chickens are mainly reared for subsistence purposes [8], but the current review suggests rearing them for both consumption and income to alleviate hunger and poverty. This is important for creating opportunities and solutions to transform the traditional village chicken production for the market and commercialization while improving livelihoods.

Due to global food challenges such as increased food prices, most individuals suffer in resource-poor communities in developing countries [9]. As a solution, village chicken eggs and meat can be used as a substitute or alternative at a low cost, with a good nutritional profile and sensory properties. The projection is to expand the poultry market, which will continue to grow as the demand for food increases. In this case, agricultural development is suggested as the primary tool for economic growth, especially for vulnerable groups based in resource-poor communities. Given the challenges of unemployment and the absence of sustainable livelihoods, coupled with the increasing digitization of the world, individuals run the risk of facing hardship if they lack the necessary skills and opportunities. Developing agricultural activities in resource-poor communities has the potential to encourage the youth to create opportunities for disadvantaged groups and alleviate drug use, unemployment, poverty, and gender-based violence.

Individuals in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs) are susceptible to poverty and hunger and can be included in the vulnerable group. However, Desta et al. [10] indicated that village chicken production is a tool used to support the livelihoods of vulnerable and disadvantaged groups. On the other hand, the lack of a market, extension services, high cost of feed, zero training, and absence of scientific education and knowledge on village chickens might be the contributing factors to the low productivity of village chickens [11].

Village chickens are adjusted to harsh rearing conditions, as most farmers rearing these chickens are challenged socio-economically and are resource-poor. However, there is an opportunity for village chickens to participate in the mainstream value chain and improve livelihoods, especially in rural areas. Exploring village chicken production is required to improve its management, end products, and consumer acceptability. This can be achieved by investigating village chicken meat, egg, and by-product quality and sensory effects on improving their consumer acceptability to generate income beyond the current threshold [12]. This literature review addresses how village chickens can potentially achieve No Poverty and Zero Hunger in resource-poor communities found in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs).

2. Materials and Methods

A literature review on village chickens for achieving Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 2 in resource-poor communities was conducted using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13].

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility of the study was assessed in terms of the countries investigated, population group, type of chickens and products, ecotype and breed, challenges, and improvements. For eligible countries, studies included were in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries and sub-Saharan countries that rear village chickens for various reasons. Studies accepted were those that (i) focused on village chicken production within the country; (ii) were accessible for full review and written in English; (iii) were reporting original research; (iv) were focused on village chicken products; (vi) were published in a peer-reviewed journal (not pre-prints). For the quantitative synthesis, accepted studies were those that employed either a randomized experiment or a quasi-experimental methodology. The qualitative synthesis included studies that met two criteria: (1) studies with well-defined research objectives and connections to relevant literature and (2) studies that provide comprehensive information on context, sample selection, and data collection procedures.

Databases of academic papers, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, were used to search for the literature of this review. English-language written articles from peer-reviewed publications were searched using the following keywords: “village chickens” OR “indigenous chickens” AND “food security” OR “food insecurity” AND “sustainable development goals” OR “no poverty” OR “zero hunger” AND “village chicken products” OR “meat” OR “eggs” OR “internal organs” OR “offals” AND “gender dynamics” OR women empowerment” AND “resource-poor communities” OR “Low-Income Deficit Countries OR sub-Saharan Africa” OR “Developing countries”. The consideration of studies for inclusion was based on the study being a survey or a review conducted in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries, sub-Saharan Africa, and developing countries, and other research articles from all over the world were used to explain other literature review findings.

3. Characteristics of Village Chicken Production

The human population in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs) is growing rapidly with the pressure of transitioning to high-income countries with an expected high demand for animal protein [14]. Village chicken production is essential for resource-poor communities [15], as they are regarded as one of the domesticated avian species reared to benefit humans with lower socio-economic status. Various studies have revealed that village chickens are essential in improving the socio-economic status of many resource-poor communities [16]. Therefore, investing in small-scale farming creates great returns that have the potential to alleviate poverty and improve food security [17]. Village chickens are abundant in communities that are challenged mainly by food insecurity, and they mostly contribute as a source of high-quality protein and bioavailable micronutrients and income to vulnerable groups [18].

Village chickens play a role economically, socially, and nutritionally, with the ability to empower women to support livelihoods within the household. They play a crucial role in sustainable agriculture because they help control pests and insects in crops, provide natural fertilizer, and reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Furthermore, they have cultural significance in numerous communities, with their production and consumption deeply rooted in local traditions and customs. Preserving cultural heritage can help promote community identity and social cohesion.

Village chickens can be one of the interventions to achieve Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, such as 1-No Poverty, 2-Zero Hunger, 3-Good Health and Well-Being, 4-Gender Equality, and 10-Reduce Inequality. The studies of Wong et al. [19] and de Bruyn et al. [20] suggest that village chickens contribute to different Sustainable Development Goals, as they have direct and indirect benefits, such as contributing to the creation of human capital through the health of poor people.

In addition, the recommendation by the FAO [21] is that village chickens are significant as a protein source. Despite that, Asem-Bansah et al. [22] revealed that in sub–Saharan Africa, for children who suffer from micronutrient deficiency, village chickens are used as a solution due to their availability and accessibility to increased micronutrient-rich protein. Malnutrition results from poor diets with daily diet intake that lacks nutritionally dense food, such as high animal protein (meat and eggs), that consists of various essential micronutrients and high bioavailability forms [23]. Table 1 below indicates village chicken production in LIFDCs. Ghana, Niger, Zambia, and Bangladesh had over 90% of farmers rearing village chickens, whereas Indonesia had the lowest number of farmers.

Table 1.

Village chicken production in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs).

3.1. Village Chicken Meat for Food and Nutrition Security and Alleviating Poverty and Hunger

The growth and development of humans and animals is dependent on animal protein, as most of the nutritional components are needed in sufficient quality and quantity. Hence, its availability and access are minimal, especially in resource-poor communities, due to socio-economic challenges.

Meat is a food source that provides a nutritious supply of protein, minerals, vitamins, and various micronutrients [30]. Thailand had a high demand for village chicken meat due to its unique nutritious taste and texture [31]. Following this, Smith et al. [32] mentioned that meat and eggs are considered sources of high-quality protein and micronutrients, and vulnerable groups mostly prefer to sell animal-source food for cultural practices rather than personal consumption.

In South Africa, village chicken meat is the primary tool used to attain dietary protein and nutrient requirements for individuals based in resource-poor settings [33]. Moreover, Motsepe et al. [34] indicated that village chicken production plays a role in the economy and food security for smallholder farmers in rural settings. Bett et al. [33] concluded that village chicken products such as meat and eggs are underutilized products in rural and urban areas, consumers highly prefer them, and their consumption should be recommended. They are also recommended for individuals who prefer low-fat and antibiotic-free white meat and are said to be free from drugs and hormones. In contrast, farmers are incognizant of the value of village chickens since they are treated as pets.

3.2. Women’s Empowerment Playing a Role in Village Chickens

Village chickens are generally owned and managed by women and the youth and are an important aspect of female-headed households. According to the FAO [35], village chickens are considered unique and valuable to women and children. Enhancing their production can address and reduce gender inequalities that exist in livestock production. The key point to support women’s empowerment is village chickens because of the returns from meat and eggs through sales generated by women. Rearing village chickens can create employment opportunities and skill development for community members through farming, especially women and youth. These individuals can be employed as chicken feed suppliers, caretakers, or sellers of chicken products. In India, village chickens support women and unemployed youth by lowering the demand and increasing the supply of chicken products such as meat and eggs [36].

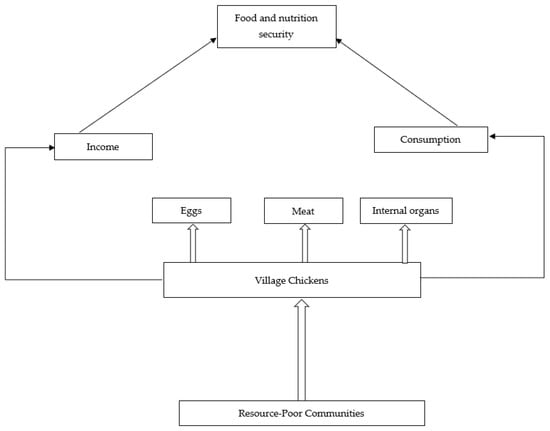

Empowering women is a tool that can provide women with power or control concerning decision-making regarding consumption, distribution, and sales. At the same time, empowerment is referred to as an indicator of access because when food is available through a woman, food will be accessible to every family member [37]. Their role is to maximize production while ensuring the quality and safety of the food within the household and control feed distribution. Hence, there are certain inequalities where men are given more food than women and children, which has a negative impact on the nutritional well-being of other family members who receive lesser quantities. Women’s empowerment can be achieved through the provision of knowledge and full control over village chicken production. Dumas et al. [15] in Kenya argued that no scientific evidence exists that women’s empowerment improves household welfare. Whereas in Bangladesh, it was reported that the empowerment of women significantly impacts the health, nutrition, education, and overall well-being of societies, as well as that of children and households. Improving village chicken production is interlinked with food and nutrition security, which positively impacts men and women per capita [38]. Figure 1 below indicates how village chickens can potentially contribute to achieving No Poverty and Zero Hunger in resource-poor communities.

Figure 1.

Village chicken contribution potential to achieving No Poverty and Zero Hunger in resource-poor communities.

3.3. Informal Value Chain of Village Chickens

Village chickens have been neglected with regard to their ability to participate in the value chain [26]. The value chain of village chicken starts with the producers (farmers) within the household who sell village poultry products to retailers (neighbors) who are regarded as consumers. The products produced by village chickens in the value chain are mainly live birds, meat, and eggs, and they all serve different purposes for different consumers. Similar to the argument of Yadeta et al. [39], there are significant channels where farmers sell their chickens, usually directly to consumers in large urban centers. However, Momoh et al. [40] indicated that not all village chickens will be suitable to participate in the mainstream value chain due to their poor nutritional status. Therefore, it is recommended that supplementation and interventions be provided based on the village chicken production system. However, Wilson [41] specified that constraints to the village chicken value chain include a lack of proper supervision, poor industry association, contradictory roles and mandates in the administration, and lack of market coordination.

4. Challenges of Village Chicken Production

There are critical challenges for village chicken production, such as diseases, predation, poor health status, feed sources, and poor marketing strategies [42]. In addition, village chickens are challenged by high mortality rates due to diseases, lack of infrastructure, low production performance, lack of scientific knowledge, and predation [36]. Hence, these challenges that village chickens face depend significantly on the rearing system type, including inputs and outputs within the household. In LIFDCs, village chicken production is dominant, but there are gaps and opportunities due to low inputs and outputs. Outputs are the relationship between production and productivity, consisting of what was used and produced under harsh conditions [43]. Inputs include feeds, vaccines, housing, training, equipment, and veterinary services [44]. However, village chicken production fits well in the environmental conditions of resource-poor communities due to lower feed costs, affordable space, and low inputs and outputs [39].

In most African countries, mainstream agriculture and other activities have excluded the village chicken production system, and presently, the world faces climate change that affects livestock production. At the same time, results in [45] showed that village chickens significantly differ in adaptation traits in harsh and changing environmental conditions compared to modern breeds such as other livestock. Farmers rearing village chickens depend greatly on limited resources and engage in different activities to achieve sustainable livelihoods. That is why village chickens have low output compared to intensively reared chickens, such as broilers with high input and high output.

4.1. Lack of Access to Quality Feed and Nutrition for Village Chickens

Generally, village chickens survive through the scavenging system with little or no feed supplement (maize) and kitchen waste, which mainly depends on the household’s socio-economic status. This is in line with Mekonnen [46], who revealed that rearing village chickens requires a certain amount of supplementary feed, such as maize and leftover food. In contrast, Alders et al. [47] indicated that the scavenging system frequently provides not more than 60–70% nutrients with minimal or no supplementary feeding. On the other hand, Olwande et al. [48] revealed that 100% of household farmers are using cereal grain as a food supplement for village chickens. The feeding strategies employed for chickens contribute about 30% of the overall meat production [47], and feed supplementation is vital for village chickens to achieve optimum production with a low input level [48]. Elagib et al. [49] suggested that hematological changes can be used to measure the nutrition of village chickens and determine if these birds are receiving sufficient nutrition requirements.

Scavenging for feed results in chickens that are small in stature genetically and are thus unable to produce and reach their genetic potential due to these unfavorable conditions [41]. There is a correlation between input costs such as labor, feed, and health, which are relatively low and yield low outputs in any production system, mainly in terms of live weight, meat, and eggs [50]. This is intensified by the village chicken production system that depends on family labor and inefficient feed requirements through scavenging [19]. The low feed efficiency is a disadvantage, although the economic strength of production cost depends on outputs through income and the provision of protein that contributes nutritionally and economically [51].

4.2. Diseases

The bio-security measures recommendation from authorities is not matched in village chicken production, including handling sick birds that contribute to the high prevalence of diseases [52,53]. As Mohammed [42] indicated, the experience and attitudes of resource-poor communities toward handling sick birds contribute to the high prevalence of diseases in these communities. The most common infectious disease that decreases production and reproduction performance in village chickens is Newcastle disease (ND) [54]. Furthermore, the leading killer of village chickens is Newcastle disease (ND) [25]. Moreover, Dana et al. [45] indicated that scavenging as a part of this production system with no vaccination program is the highest driver of losing village chickens due to disease susceptibility. Also, Motsepe et al. [34] indicated a significant benefit in the health promotion of village chickens based in South Africa that were fed commercial feed to enhance their meat quality characteristics from 1 day old until 18 weeks.

In LIFDCs, diseases in village chickens such as Newcastle can potentially reduce the flock by 80%. In the study of Mohammed [42], results indicated that from farm visits, these were diseases affecting village chicken production: Newcastle disease (71%), other (29%), Coccidiosis (0.83%), and external parasite (0%). The high mortality rate from the abovementioned diseases constitutes a significant hindrance to improving productivity and production. Village chicken owners use herbs such as Aloe Vera, pepper, and sisal leaves for treatment and disease control [48]. However, the most prevalent diseases affecting village chickens are Newcastle, Gumboro, and fowl pox diseases [48].

4.3. Recordkeeping

Farmers have been rearing village chickens for decades, using indigenous knowledge without keeping records. It was found that in resource-poor communities, no data were collected and maintained for village chickens; thus, no historical information is available, including clutch number, mothering ability, health records, and mortality rates.

The major challenge is that farmers lack scientific knowledge on rearing and usually rely solely on indigenous knowledge to manage the flock. Omondi [55] revealed that no records are kept for village chickens, and farmers provide data on flock size and inputs based on their recollection. Desta [56] added that recordkeeping for village chickens can be used to track and assess the flock to make decisions based on their performance and management. Integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge can benefit farmers by maximizing outputs [57].

4.4. Inadequate Housing and Shelter for Village Chickens

Poor housing and shelter for village chickens exposes them to various challenges, such as theft and predation, that result in lowering the flock size. The results of Tenza et al. [58] indicated a significant odds ratio between the present and absence of housing in village chicken production. The low production of village chickens is due to poor management in terms of feeding and housing [59]. Therefore, providing shelter for village chickens is crucial to protect them from adverse weather, theft, and predators [50]. Many of these shelters are constructed using materials found locally. Currently, the provision of housing and shelter for village chickens is rudimentary. This negatively contributes to low outputs of the chickens, which results in birds having to roost in trees and shrubs. For adult birds, trees are well ventilated and away from predators. Therefore, poorly maintained chicken houses contribute to external parasite infestations and predation.

4.5. Limited Market Access and Low Market Prices for Village Chicken Products

The village chicken marketing system is poorly developed and informal [60,61]. Currently, in South Africa, there is no formal market for village chickens, and farmers create their traditional market, selling locally and in the vicinity. Sometimes, farmers barter to exchange live chickens and eggs. Others are referred to as village chicken vendors. They are based in the Central Business District, selling chickens as their source of income. The market price is determined by the weight, sex, number of eggs produced, and growth rate [45].

The poultry age of slaughter depends on the market demand, and their products are based on sales and production [62]. According to Wattanachant [31], village chickens aged 16 to 18 weeks are suitable for consumption based on their live weight and meat quality.

4.6. Gender Inequality in Poultry Ownership and Decision-Making

There are concerning gender inequalities that are intra-household dynamics that affect or reveal inequities such as food distribution. Where a significant difference in gender, ownership, and utilization of resources is very high, village chickens are considered a symbol of gender equity [19].

Economically, village chicken production empowers women through animal source foods and income. Women and children contribute to the food and nutrition of the households in different aspects of the value chain. However, their role in village chicken production is not equal to that of men, and policymakers and researchers ignore their contribution. In contrast to other livestock, such as ruminants, women and children have limited participation, but they frequently have high participation rates as carers and shepherds, whereas with village chickens, they exercise significant control [63].

Various studies depicted that cultural anecdotes affect and limit women’s participation in rearing village chickens, such as decision-making, ownership, and control of income generated through chicken products. Gender inequality that exists can potentially expose challenges and opportunities for innovation such as technology, funding, and more research in village chicken production. Akite et al. [64] indicated that in the value chain of village chickens, males dominate the most in marketing, sales, and housing construction, while women only participate in production and food preparation. Akite et al. [64] concluded that men reap greater rewards from village chickens, whereas women often find themselves overextended with the responsibilities of chicken while receiving little in return. However, controlling challenges of village chickens, such as Newcastle disease, will result in increased production, food security, and food sovereignty, and the economic status of women will be improved [65].

4.7. Traditional Beliefs and Cultural Practices That Affect Village Chicken Rearing

Cultural practices are important in communities and are known for their influence on dietary practices or consumption patterns globally [66]. Individuals in resource-poor communities rely on indigenous knowledge influenced by culture to rear village chickens. For example, they have not opted to depend on scientific knowledge due to a lack of access to extension and education services in underserved areas with high external inputs, chicken breeds, and medicinal treatment [67]. Indigenous knowledge from ancestors and forefathers to rear village chickens has disappeared [68]. Hence, they rely on the socio-economic status of the households and the availability and access of channels around the community, such as extension services by the government.

4.8. Role of Education and Training in Promoting Sustainable Village Chicken Rearing Practices

Interventions such as training and workshops are not provided for farmers in resource-poor communities. It is evident in the study of Tenza [69] in South Africa that 0% of village chicken vendors were exposed to chicken farming, and over 85% were interested in attending trainings. Training is crucial for fostering new perspectives and enhancing knowledge and skills in village production systems [36]. Alam et al. [70] argued that farmers who rear village chickens have no satisfactory knowledge of poultry production. Effectively managing the ownership of village chickens within the house requires allocating limited resources such as time, energy, money, land, and water. In LIFDCs, village chickens are associated with low input, poor production, and high mortality. This aligns with Olwande et al. [48], who indicated that village chickens’ low productivity is related to low inputs. Then, it was suggested that input on management could be improved by parameters such as clutch size, chick survival, and body weight gain.

Village chickens demonstrate technical efficiency by maximizing output with the available inputs. Traditionally, with indigenous knowledge, there is no production plan for village chickens—such as reproduction and incubation—depending on chickens, which includes no or a minimal housing system. It is recommended that farmers are well equipped with scientific knowledge of the extension program to improve the inputs and outputs of village chickens [71].

5. Common Chicken Breeds in Resource-Poor Communities

There are different breeds and ecotypes found in resource-poor communities, and their function varies from consumption, sales, and cultural practices. In sub-Saharan countries, Nigeria has the highest number of village chickens [72]. In resource-poor communities, village chickens have a particularly significant role [73], even though they differ based on geographical areas and phonetical traits. However, genotypic differentiation is limited [74]. Even though they have very strong adaptive traits, village chicken breeds tend to have relatively lower growth rates and body size [75].

5.1. Potchefstroom Koekoek

In South Africa, the Potchefstroom Koekoek breed is widely recognized as a dual-purpose chicken breed that is kept for both meat and egg production [76]. Compared to other village chicken breeds in South Africa, it is regarded as the best performer [77]. The study of Tenza [69] conducted in South Africa exhibited that Potchefstroom Koekoek, also known as Impangela, was discovered to be among the breeds that are in demand and sold by street vendors in the informal market of KwaZulu-Natal for cultural purposes.

This breed is considered a heavy breed, as the average weight for roosters is 1.84 kg at 16 weeks and for hens, 1.4 kg at 16 weeks [78]. Male chickens were also reported to grow faster than females [79]. It was then concluded that more research is required on village chicken breeds in South Africa to differentiate their breeds on their genotypic and phenotypical traits [80].

5.2. Non-Descript Breeds

Non-descript breeds are closely linked to chickens that exhibit variations in color, comb type, body structure, and weight and may or may not have shank feathers [81]. However, a breed like Black Australorp is closely related to some non-descriptive breeds most used in resource-poor communities due to crossbreeding in the flock. However, Black Australorp is an exotic breed and the most essential imported breed used in resource-poor communities in South Africa. It is also a dual breed reared for eggs and meat; they are hardy and prolific layers and have been introduced to various genetic improvement programs [82]. They adapt well to tropical environments and can survive scavenging for feed resources [80]. Their males have a higher adult weight, ranging from 3 to 4 kg [83]. This concurrence is supported by Fourie et al. [84], who indicated that the Black Australorp males have an average body weight of 3.85 kg and 2.94 for females.

5.3. Broiler Chickens

A broiler chicken is any chicken bred and reared for meat production [85]. In broiler chickens, genotype and the environment influence the maturity stage, body weight, and the ratio of fat, water, and ash deposition, which characterize the physiological age of the chicken [86]. Commercial broilers supply different markets that vary with communities, customs, and economic sectors, and live chickens are sold in other countries [87]. The above-mentioned concurs with the study of Tenza [69], which states that in the informal market, broiler chickens compete with various breeds of village chickens in demand in the Central Business District in KwaZulu-Natal.

6. Internal Organ Weights of Chickens and Sensory Evaluation

Internal organs of village chickens are another underutilized niche that has the potential to contribute to food security as a protein source. Exploring this product through the sensory evaluation of consumers is recommended. The main reason for rearing village chickens is to improve productivity and their genetic material to increase body weight, yielding a high carcass percentage [88]. The percentage of the carcass is influenced by various factors such as breed type, age, sex, feed, fat weight, and internal organ weight [89]. However, limited information that predicts the weight of the important aspect of chickens, which varies with age, weight, strain, and sex, is available. Broiler producers have never reported data on the relationship between internal organs, body weight, and live weight during growth [87]. Butzen et al. [90] argued that investigating the correlation between live weight, internal organs, and body part weights of broiler chickens will provide valuable insight for animal scientists. This research can serve as a reference during carcass analysis and aid in predicting the weight of various internal organs and body parts based on live and carcass weight. Consequently, this means that the weight of organs, such as the gizzards, can be estimated without the need to slaughter the bird.

Sensory analysis is undeniably integral to scientific methods. It stands as one of the earliest quality control methods and is fundamentally essential for evaluating food quality. Moreover, it delves deeper into studying the intricate relationship between physiological and psychological phenomena in the process of perceiving sensory attributes [91]. There are perceptions related to village chicken meat, such as that it is very flavorsome and contributes to high meat demands in African countries [92]. Village chicken meat is highly recommended due to its nutritional taste compared to exotic chicken genotypes [93]. For example, Potchefstroom Koekoek meat is favored at the same level as broiler chickens [94]. The following traits of village chickens are preferred mainly by consumers: carcass color, toughness of muscle meat, eggshell color, and yolk color.

7. Improving Village Chicken Production for Food and Nutrition Security

The role of village chickens is to improve livelihoods in resource-limited households while creating income and opportunities. Local consumers prefer eggs and meat from village chickens as opposed to hybrid and exotic breeds [42]. Similarly, consumers prefer village chickens over broilers in other countries because of their low fat content [26]. As a result, in Ethiopia, one of the LIFDCs, village chickens contribute to more than 90% of the national chicken meat and eggs [45].

Improving village chicken productivity focuses on enhancing management parameters by increasing access to related markets and increasing ownership by vulnerable groups. High hatchability while breeding to improve productivity is required in resource-poor settings and environmental conditions [45]. Evidence from Walton et al. [95] revealed that village chickens have the potential to contribute to animal protein during a shortage of food in resource-poor settings. Results from Birhanu et al. [96] showed that in different LIFDCs, mainly Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Nigeria, village chickens generated an income of 18, 1, 52, 8, and 44.7 USD, respectively, in the period of 3 months.

In the study of Guan et al. [97], it was revealed that meat quality differs with the type of breed. Five village chicken breeds were compared amongst themselves and commercial chickens, and there was a significant difference in traits such as body weight, pH, shear force, and drip loss. According to Partasasmita et al. [68], results indicated that different breeds of village chickens are sourced by buying from neighbors (43%), relatives (24%), and parents (21%). This indicates that village chickens are obtained internally and are not exported in South Africa. This agrees with Toledo [67], who revealed that local cultural beliefs embed village chickens.

Enhancing food availability and safety through advancements in village chicken production, incorporating innovative interventions such as improved breeds, animal health management, and technologically enhanced feed during the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution are necessary to improve the status quo of village chickens. Introducing technology in village chicken production can enhance the quality and quantity of output in Low-Income Food Deficit Countries with limited resources while considering the input level. Birhanu et al. [96] highlighted that adding technology such as quality feed and management intervention in village chicken production can produce great outputs despite minimal inputs.

Policymakers and researchers can be influenced to enhance village chicken productivity by acknowledging its potentially significant role in alleviating food insecurity and improving the nutritional status in resource-poor households in marginalized environments while diverting food from households to the market. Village chicken production can improve population health and help overcome malnutrition food and nutrition insecurity in resource-poor households in LIFDCs. It will also create opportunities for the youth in resource-limited households to participate in the study and promote interest in the agricultural sector.

Improving village chicken production through nutritional program practices is recommended rather than focusing on enhancing breeds [98]. Approximately 20–30% of village chickens play a role in resource-poor households as a source of animal protein and micronutrients [19]. Resource-poor households frequently keep village chickens to fulfill various purposes [76]. In LIFDCs, their primary objectives for rearing village chickens are to generate income through sales and meat and egg supply for household consumption of meat and eggs to improve the quality of their diets. Romero-López [99] indicated that village chickens contribute to food security and the generation of income, whereas Birhanu et al. [96] concluded that village chickens consist of low production and productivity; hence, they merely support livelihoods and smallholder farmers in Africa. On the other hand, a study by Omondi [55] revealed that village chicken production is regarded as feasible and profitable in urban areas for urban agriculture based in LIFDCs.

Diverse roles are assigned in households depending on their strategies to improve production and welfare; these strategies include experience, knowledge, and resources with values and objectives. Chicken production is characterized by unlimited production, which consists of a low number of eggs per year and a small clutch number of late-maturing hens that affect late age at first laying. Village chicken production requires minimal or no cost, yielding output that can be converted to profit or economic returns and a protein source that can significantly contribute to food and nutrition security in resource-limited household livelihoods. Inputs need to be prioritized to improve village chicken intervention. This aligns with the results of Desta [100], who revealed that management needs to be changed significantly to enhance the productivity of village chickens. Availability in food security refers to available food of high quality and acceptability. In many LIFDCs, village chickens are the most abundant farm animals in resource-poor households as a source of nutrients for a household, and they produce manure and pest control for vegetables [19]. Birhanu et al. [96] agreed that village chickens can transform low-quality feed from scavenging and kitchen leftovers and supply high-quality protein and manure for crops.

7.1. Women in Improving Village Chicken Production

Studies in LIFDCs indicated that women’s source of income is from village production through the sale of eggs, meat, and live chickens [101]. To maximize production output, women are challenged by limited access to training and resources. Due to culture and religion, women are unable to grow and yield more output, as they are still suffering from inequalities. Women are still unable to access education and employment outside their homes. As indicated by Westholm et al. [102], gender has control over production, as women have limited access to inputs compared to men and are excluded in land, input distribution, and policymaking.

When prompted to rank livestock in their order of importance using a ladder ranking method, women consistently place village chickens at the top in Kenya. In contrast, men consistently rank village chickens at the lowest, with cattle being their preferred choice. Limited economic resources and a lack of access to financial markets and banking services hinder smallholder farmers’ ability to secure the required support to enhance their businesses. Padhi [27] revealed that the type of production technologies, markets, management, and environmental constraints are in conjunction with the low production of village chickens.

7.2. Flock Size for Improving Village Chicken Production

The FAO 2008 revealed that flock size is influenced by management conditions with an existing production system that can either be commercial, village, or small-scale. The flock size of the household includes the total number of village chickens kept. It can be small or large. The flock size is relatively dependent on inputs and management strategies that reduce the high mortality rate associated with mothering ability, predation, and hatchability in village chicken production. Desta [56] indicated that village chicken flock size is small, with a total number of fewer than 100 birds of different ages and sexes, which makes their management challenging as their growth stages are not the same in terms of requirements in Ethiopia. The system consists of a chicken flock with various birds of different ages and sexes.

8. Conclusions

Village chickens play diverse roles, providing nutrition, environmental benefits, cultural significance, economic support, social cohesion, and recreational enjoyment. However, their true value remains obscured, underestimated, and untapped, as they have been neglected for decades and lack a market. Their resilience is noteworthy as their unique characteristic and is evident in their ability to survive and reproduce despite challenging conditions, including irregular access to water and feed and a lack of healthcare. Village chickens’ productivity is hampered by minimal inputs, resulting in low output, a lack of technological advancements, and the slow dissemination of scientific knowledge, all of which impede village chicken production.

Village chickens have the potential to contribute sustainably to enhancing food security and nutrition in LIFDCs, aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1 (No Poverty) and 2 (Zero Hunger), which aim to achieve food security, improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture, especially for vulnerable groups such as women and children. This can also be an opportunity for women’s empowerment and addressing gender inequalities through village chickens in resource-poor communities. Introducing interventions such as animal health services and livestock extension programs is essential to maximizing village chicken production. The literature indicates that implementing strategies and innovative approaches, including raising awareness, implementing development projects, providing technological information, and offering education and inputs, is crucial for achieving higher output and productivity.

The challenge of accessing productive resources, markets, and technology presents an opportunity to enhance production and productivity by leveraging available inputs in conjunction with technology. Examining and comprehending the key inputs necessary for village chicken production can serve as an innovative approach to crafting productivity, thus enhancing policies and strategies. However, research focusing on improving village chicken production remains scarce.

It is crucial to enhance village chicken production while preserving the authenticity of indigenous breeds. In LIFDCs, access to channels facilitated by policymakers and governments is essential, as it provides resources and infrastructure, including knowledge transfer and training for farmers. Establishing networks among resource-limited communities to collaboratively rear village chickens in a systematic manner is necessary. Policymakers should actively engage in formulating and implementing policies that empower women through village chicken production, enabling their participation in mainstream value chains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T. and L.C.M.; methodology, T.T.; validation, C.N.N. and Z.R; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T.; resources, T.T.; data curation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, L.C.M.; visualization, Z.R.; supervision, Z.R and C.N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to it consisting of a literature survey that does not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

All data, tables, and figures in this manuscript are original.

Acknowledgments

Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems (SHEFS) program of the Welcome Trust’s Our Planet, Our Health program [Grant Number: 205200/Z/16/Z]. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO; IFAD. Farmer Field Schools for Family Poultry Producers—A Practical Manual for Facilitators; FAO: Rome, Italy; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Raney, T. The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Dev. 2016, 87, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Family Poultry Development–Issues, Opportunities and Constraints; Animal Production and Health Working Paper 12; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gc, R.K.; Hall, R.P. The commercialization of smallholder farming—A case study from the rural western middle hills of nepal. Agriculture 2020, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022: Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J.D.B.; Reidsma, P.; Giller, K.; Todman, L.; Whitmore, A.; van Ittersum, M. Sustainable development goal 2: Improved targets and indicators for agriculture and food security. Ambio 2019, 48, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S. Towards a sustainable agriculture: Achievements and challenges of Sustainable Development Goal Indicator 2.4.1. Glob. Food Secur. 2023, 37, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryemo, I.P.; Akite, I.; Kule, E.K.; Kugonza, D.R.; Okot, M.W.; Mugonola, B. Drivers of commercialization: A case of indigenous chicken production in northern Uganda. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2019, 11, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, M.Y.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Obese, F.Y.; Dessie, T. Smallholder poultry production in the context of increasing global food prices: Roles in poverty reduction and food security. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desta, T.T.; Wakeyo, O. Uses and flock management practices of scavenging chickens in Wolaita Zone of southern Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natukunda, K.; Kugonza, D.; Kyarisiima, C. Indigenous chickens of the Kamuli Plains in Uganda: II. Factors affecting their marketing and profitability. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2011, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Maumburudze, D.; Mutambara, J.; Mugabe, P.; Manyumwa, H. Prospects for commercialization of indigenous chickens in Makoni District, Zimbabwe. Livest. Res. Rural. Dev. 2016, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, H.D.; Vasco, K.A.; Zhang, L. A review of antimicrobial resistance in poultry farming within low-resource settings. Animals 2020, 10, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, S.E.; Maranga, A.; Mbullo, P.; Collins, S.; Wekesa, P.; Onono, M.; Young, S.L. “Men are in front at eating time, but not when it comes to rearing the chicken”: Unpacking the gendered benefits and costs of livestock ownership in Kenya. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinka, H.; Chala, R.; Dawo, F.; Leta, S.; Bekana, E. Socio-economic importance and management of village chicken production in rift valley of Oromia, Ethiopia. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2010, 22, 203. [Google Scholar]

- Pica-Ciamarra, U.; Otte, J. Poultry, food security and poverty in India: Looking beyond the farm-gate. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraval, S. Food Security in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa: A Household Level Assessment of Mixed Crop-Livestock Systems; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.; de Bruyn, J.; Bagnol, B.; Grieve, H.; Li, M.; Pym, R.; Alders, R. Small-scale poultry and food security in resource-poor settings: A review. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 15, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyn, J.; Wong, J.; Bagnol, B.; Pengelly, B.; Alders, R. Family poultry and food and nutrition security. CABI Rev. 2015, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Livestock: Transforming the Livestock Sector through the Sustainable Development Goals; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; 222p. [Google Scholar]

- Asem-Bansah, C.K.; Sakyi-Dawson, O.; Ackah-Nyamike, E.E.; Colecraft, E.K.; Marquis, G.S. Enhancing backyard poultry enterprise performance in the Techiman area: A value chain analysis. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2012, 12, 5759–5775. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Salas, P.; Galiè, A.; Omore, A.O.; Omosa, E.B.; Ouma, E.A. Contribution of Milk Production to Food and Nutrition Security; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bettridge, J.M.; Psifidi, A.; Terfa, Z.G.; Desta, T.T.; Lozano-Jaramillo, M.; Dessie, T.; Kaiser, P.; Wigley, P.; Hanotte, O.; Christley, R.M. The role of local adaptation in sustainable village chicken production. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, H.; Keambou, T.; Hima, K.; Issa, S.; Motsa’A, S.; Bakasso, Y. Indigenous chicken production in Niger. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2019, 7, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, R.; Kalinda, T. An analysis of the value chain for indigenous chickens in Zambia’s Lusaka and Central Provinces. J. Agric. Stud. 2014, 2, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, M.K. Importance of Indigenous Breeds of Chicken for Rural Economy and Their Improvements for Higher Production Performance. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, L.a.A.H. Livestock and Animal Health Statistics 2019, Directorate General of Livestock and Animal Health; Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, J.; Pym, R.; Hla, T.; Kyaw, N.; Meers, J. Village chicken production in Myanmar–purpose, magnitude and major constraints. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2007, 63, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xiong, Y.L. Natural antioxidants as food and feed additives to promote health benefits and quality of meat products: A review. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanachant, S. Factors Affecting the Quality Characteristics of Thai Indigenous Chicken Meat; Suranaree University of Technology: Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Sones, K.; Grace, D.; MacMillan, S.; Tarawali, S.; Herrero, M. Beyond milk, meat, and eggs: Role of livestock in food and nutrition security. Anim. Front. 2013, 3, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, H.; Peters, K.; Nwankwo, U.; Bokelmann, W. Estimating consumer preferences and willingness to pay for the underutilised indigenous chicken products. Food Policy 2013, 41, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motsepe, R.; Mabelebele, M.; Norris, D.; Brown, D.; Ngambi, J.; Ginindza, M. Carcass and meat quality characteristics of South African indigenous chickens. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2016, 50, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Decision Tools for Family Poultry Development; FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines No. 16; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Dahiya, S.; Ratwan, P. Backyard poultry farming in India: A tool for nutritional security and women empowerment. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2021, 52, 1476–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, A.; Teufel, N.; Girard, A.W.; Baltenweck, I.; Dominguez-Salas, P.; Price, M.J.; Jones, R.; Lukuyu, B.; Korir, L.; Raskind, I.; et al. Women’s empowerment, food security and nutrition of pastoral communities in Tanzania. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 23, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Gajanan, S.; Sanyal, P. Effects of commercialization of agriculture (shift from traditional crop to cash crop) on food consumption and nutrition—Application of chi-square statistic. Food Secur. Poverty Nutr. Policy Anal. 2014, 2, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yadeta, K.; Dadi, L.; Yami, A. Poultry Marketing: Structure, Spatial Variations and Determinants of Prices in Eastern Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. In Proceedings of the Challenges and Opportunities of Livestock Marketing in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 22–24 August 2002; Volume 69. [Google Scholar]

- Momoh, O.; Egahi, J.; Ogwuche, P.; Etim, V. Variation in nutrient composition of crop contents of scavenging local chickens in North Central Nigeria. Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 2010, 1, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. The White Meat Value Chain in Tanzania. Food Agric. Organ. World Rabbit. Sci. 2015, 7, 8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A. Major constraints and health management of village poultry production in Ethiopia: Review school of veterinary medicine, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia. J. Res. Stud. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Alders, R.G.; Dumas, S.E.; Rukambile, E.; Magoke, G.; Maulaga, W.; Jong, J.; Costa, R. Family poultry: M ultiple roles, systems, challenges, and options for sustainable contributions to household nutrition security through a planetary health lens. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, A.; Gebremedhin, B.; Hoekstra, D. Input Supply System and Services for Market-Oriented Livestock Production in Ethiopia; Ethiopian Society of Animal Production: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, N.; van der Waaij, L.H.; Dessie, T.; van Arendonk, J.A.M. Production objectives and trait preferences of village poultry producers of Ethiopia: Implications for designing breeding schemes utilizing indigenous chicken genetic resources. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, G. Characterization of the Small Holder Poultry Production and Marketing System of Dale, Wonsho and Loka Abaya Weredas of Snnprs; Hawassa University: Awassa, Ethiopia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alders, R.G.; Pym, R.A.E. Village poultry: Still important to millions, eight thousand years after domestication. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2009, 65, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwande, P.O.; Ogara, W.O.; Okuthe, S.O.; Muchemi, G.; Okoth, E.; Odindo, M.O.; Adhiambo, R.F. Assessing the Productivity of Indigenous Chickens in an Extensive Management System in Southern Nyanza, Kenya; Springer Science + Business Media, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elagib, H.; Ahmed, A. Comparative study on haematological values of blood of indigenous chickens in Sudan. Asian J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 5, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, T.T.; Wakeyo, O. Village chickens management in Wolaita zone of southern Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2013, 45, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiban, C.; Robinson, T.P.; Fèvre, E.M.; Ogola, J.; Akoko, J.; Gilbert, M.; Vanwambeke, S.O. Early intensification of backyard poultry systems in the tropics: A case study. Animal 2020, 14, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, J.; Rushton, J.; Rukambile, E.; Alders, R.G. Biosecurity in village and other free-range poultry—Trying to square the circle? Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 678419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, C.; Alders, R.; Bagnol, B.; Cambaza, A.B.; Harun, M.; Mgomezulu, R.; Msami, H.; Pym, B.; Wegener, P.; Wethli, E.; et al. Improving Village Chicken Production: A Manual for Field Workers and Trainers; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR): Bruce, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alders, R.; Bagnol, B.; Young, M. Technically sound and sustainable Newcastle disease control in village chickens: Lessons learnt over fifteen years. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, S.O. Small-scale poultry enterprises in Kenyan medium-sized cities. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 9, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, T.T. The proclivity of free-ranging indigenous village chickens for night-time roosting in trees. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2021, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asten, P.J.A.; Kaaria, S.; Fermont, A.M.; Delve, R.J. Challenges and lessons when using farmer knowledge in agricultural research and development projects in Africa. Exp. Agric. 2009, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenza, T.; Mhlongo, L.; Chimonyo, M. Village chicken production and egg quality in dry and wet, resource-limited environments in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 53, 850–858. [Google Scholar]

- Selam, M.; Kelay, B. Causes of village chicken mortality and interventions by farmers in Ada’a District, Ethiopia. Int. J. Livest. Prod. 2013, 4, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, A.; Yilma, T.; Shibeshi, Z.; Workneh, T. Village chicken production systems in selected areas of Benishangul-gumuz, western Ethiopia. Asian J. Poult. Sci. 2015, 9, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queenan, K.; Alders, R.; Maulaga, W.; Lumbwe, H.; Rukambile, E.; Zulu, E.; Bagnol, B.; Rushton, J. An appraisal of the indigenous chicken market in Tanzania and Zambia. Are the markets ready for improved outputs from village production systems. Livest. Res. Rural. Dev. 2016, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Arikan; Akin, A.; Akcay, A.; Aral, Y.; Sariozkan, S.; Cevrimli, M.; Polat, M. Effects of transportation distance, slaughter age, and seasonal factors on total losses in broiler chickens. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2017, 19, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guèye, E. Gender issues in family poultry production systems in low-income food-deficit countries. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2003, 18, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akite, I.; Aryemo, I.P.; Kule, E.K.; Mugonola, B.; Kugonza, D.R.; Okot, M.W. Gender dimensions in the local chicken value chain in northern Uganda. African J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2018, 10, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnol, B.; Alders, R.G.; Costa, R.; Lauchande, C.; Monteiro, J.; Msami, H.; Mgomezulu, R.; Zandamela, A.; Young, M. Contributing factors for successful vaccination campaigns against Newcastle disease. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2013, 25, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Trefry, A.; Parkins, J.R.; Cundill, G. Culture and food security: A case study of homestead food production in South Africa. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M. Ethnoecology: A conceptual framework for the study of indigenous knowledge of nature. In Ethnobiology and Biocultural Diversity, Proceedings of the 7th International Congress of Ethnobiology, Athens, GA, USA, 23–27 October 2000; International Society of Ethnobiology, c/o University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Partasasmita, R.; Iskandar, J.; Rukmana, P.M. Naga people’s (Tasikmalaya District, West Java, Indonesia) local knowledge of the variations and traditional management farm of village chickens. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2017, 18, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenza, T. Contribution of the informal market of village chickens to sustainable livelihoods in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. East Afr. J. Biophys. Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.; Ali; Rahman, M.M.; Das, N. Present status of rearing backyard poultry in selected areas of Mymensingh district. Bangladesh J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 43, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, S.M.; Nargis, F.; Hossain, M.E.; Howlider, M.A.R.; Lee, S.H. Family poultry production and consumption patterns in selected households of Bangladesh. Soc. Dev. 2013, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Desha, N.; Bhuiyan, M.; Islam, F.; Bhuiyan, A. Non-genetic factors affecting growth performance of indigenous chicken in rural villages. J. Trop. Resour. Sustain. Sci. JTRSS 2016, 4, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machete, J.B.; Kgwatalala, P.M.; Nsoso, S.J.; Moreki, J.C.; Nthoiwa, P.G.; Aganga, A.O. Phenotypic characterization (qualitative traits) of various strains of indigenous Tswana chickens in Kweneng and Southern districts of Botswana. Int. J. Livest. Prod. 2021, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Manyelo, T.G.; Selaledi, L.; Hassan, Z.M.; Mabelebele, M. Local chicken breeds of Africa: Their description, uses and conservation methods. Animals 2020, 10, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birteeb, P.T.; Essuman, A.K.; Adzitey, F. Variations in morphometric traits of local chicken in Gomoa West district, southern Ghana. J. World’s Poult. Res. 2016, 6, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dessie, T.; Taye, T.; Dana, N.; Ayalew, W.; Hanotte, O. Current state of knowledge on phenotypic characteristics of indigenous chickens in the tropics. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2011, 67, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heit, H.L. A Comparative Study on the Growth Rates between Outbred and Inbred Chickens; International Livestock Research Institute: New Hampton, IA, USA; Borlaug–Ruan International Internship: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dessie, T.; Gatachew, F. The Potchefstroom Koekoek Breed; International Livestock Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alabi, O.; Ng`ambi, J.; Norris, D.; Egena, S. Comparative Study of Three Indigenous Chicken Breeds of South Africa: Body Weight and Linear Body Measurements, Medwell Publishing: Faisalabad, Pakistan, 2012.

- Hlokoe, V.R.; Tyasi, T.L. Quantitative and qualitative traits characterisation of indigenous chickens in Southern African countries. Online J. Anim. Feed Res. 2022, 12, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeke, S. Ethiopia: Poultry Sector Country Review; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, M.S.; Mardenli, O.; Altawash, A.S.A. Evaluation of the progeny test of some productive and reproductive traits of the black australorp chicken strain under conditions of semi-intensive housing. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S. Performance of Rhode Island Red, Black Australorp and Naked Neck Crossbred under Free Range, Semi Intesive and Intensive Housing Systems; University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences: Lahore, Pakistan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, C.; Grobbelaar, J. Indigenous Poultry Breeds, 20–21 Krugersdor 2003; Wing Nut Publications: Krugersdorp, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kruchten, T. US Broiler Industry Structure. National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS); Agricultural Statistics Board, US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vincek, D.; Kralik, G.; Kušec, G.; Sabo, K.; Scitovski, R. Application of growth functions in the prediction of live weight of domestic animals. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 20, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanacho, G.; Iwuji, T.; Ogamba, M.; Odunfa, O. Relationship between live weight, internal organs, and body part weights of broiler chickens. Malays. Anim. Husb. J. 2022, 2, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryuni, N.; Hartutik, H.; Widodo, E.; Wahjuningsih, S. Effect of energy and dose of vitamin E selenium on improving the reproduction performance of Joper brood stock. E3S Web Conf. 2022, 335, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, P.; Jiyanto, J.; Santi, M.A. Persentase karkas, bagian karkas dan lemak abdominal broiler dengan suplementasi andaliman (Zanthoxylum acanthopodium DC) di dalam ransum. Ternak Tropika J. Trop. Anim. Prod. 2019, 20, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzen, F.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.L.; Vieira, M.M.; Kessler, A.M.; Dadalt, J.C.; Della, M.P. Early feed restriction in broilers. I–Performance, body fraction weights, and meat quality. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2013, 22, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Herrero, A.M. Sensory analysis and consumer research in new product development. Foods 2021, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragasa, C.; Andam, K.S.; Asante, S.B.; Amewu, S. Can local products compete against imports in West Africa? Supply-and demand-side perspectives on chicken, rice, and tilapia in Ghana. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, M. Indigenous chicken production and the innate characteristics. Asian J. Poult. Sci. 2012, 6, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, J. Egg Production Potentials of Four Indigenous Chicken Breeds in South Africa. Master’s Thesis, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, C.; Taylor, J.; VanLeeuwen, J.; Yeudall, F.; Mbugua, S. Associations of diet quality with dairy group membership, membership duration and non-membership for Kenyan farm women and children: A comparative study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birhanu, M.Y.; Alemayehu, T.; Bruno, J.E.; Kebede, F.G.; Sonaiya, E.B.; Goromela, E.H.; Bamidele, O.; Dessie, T. Technical efficiency of traditional village chicken production in Africa: Entry points for sustainable transformation and improved livelihood. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.-F.; Lyu, F.; Chen, X.-Q.; Ma, J.-Q.; Jiang, H.; Xiao, C.-G. Meat quality traits of four Chinese indigenous chicken breeds and one commercial broiler stock. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2013, 14, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordhagen, S.; Klemm, R. Implementing small-scale poultry-for-nutrition projects: Successes and lessons learned. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-López, A.R. Bird roles in small-scale poultry production: The case of a rural community in Hidalgo, Mexico. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2021, 12, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, T.T. Indigenous village chicken production: A tool for poverty alleviation, the empowerment of women, and rural development. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, E.; Bettridge, J.; Dessie, T.; Amare, A.; Habte, T.; Wigley, P.; Christley, R.M. Participatory evaluation of chicken health and production constraints in Ethiopia. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 118, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westholm, L.; Ostwald, M. Food production and gender relations in multifunctional landscapes: A literature review. Agroforest Syst. 2020, 94, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).