The Pedagogy of the Evangelization, Latinity, and the Construction of Cultural Identities in the Emblematic Politics of Guamán Poma de Ayala

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Emblematic European Politics and New Spain

- Political. The symbolic image reaffirms political power, expressed as ‘good sovereignty’, against tyranny;

- Ideological. ‘Good sovereignty’ appears entwinned in allegorical images of mythological and fabulous natures, which include carnivalesque clothing, theatrical, and poetic works. In accordance with their symbolic capacity, the political power, habitually personified in the figure of the king, is identified with historical and mythological figures, among whom Solomon, Hercules, Atlas Perseus, Apollo, and Helios. Later on, the heliocentric debates and the texts of Bodino would motivate the introduction of other metaphors of power: the sovereign as the planetary king and pilot of the ship of State (Perceval 2003);

- Moral. The head of ‘good sovereignty’ incarnates the figure of the ‘father of State’, just and protector of the ‘family’ institution.

2. Guamán Poma de Ayala and the Primer Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno

3. The Emblematic of the Primer Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno

4. The Learning of Castilian Writing and Participation in Colonial Administrative Processes: The Ladino Indian

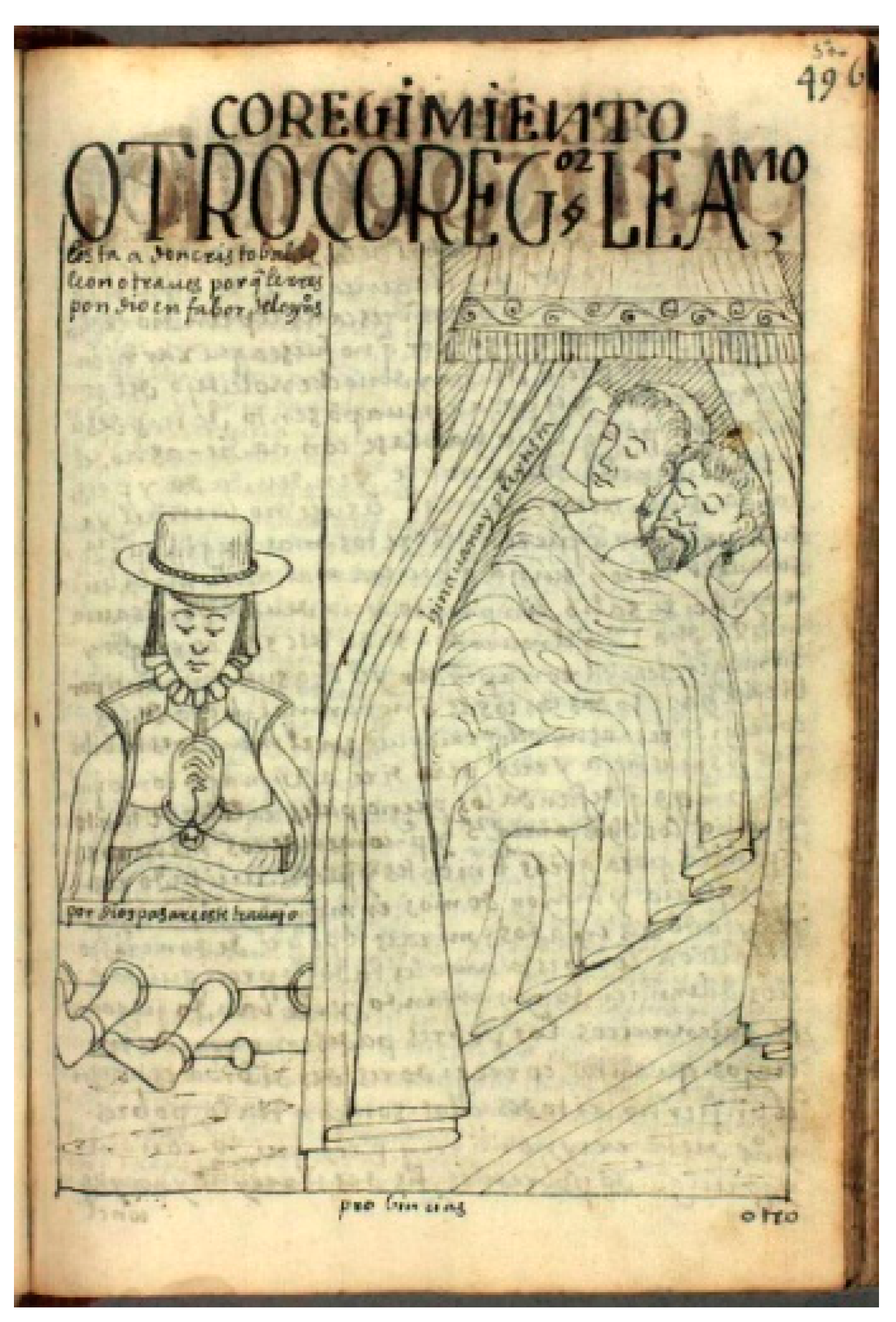

“How they make petitions those fathers and priests of the said doctrines of these kingdoms or the said vicars for returning to the said corregidores with the local chief. They draw up those petitions with their own hand and note and order a lawsuit and insist as much as they can until the earth quakes. Then they laugh at both the corregidor and the Indian chiefs: behind the scenes, they order the punishment of the Indian chief and like that they wreak their revenge.”

“The Ladino Indian expression covered a variety of social categories, referring as easily to common Indians as to the landed nobility, who possessed some knowledge of the Spanish language and customs, and maintained links with the colonial administration and the Church. The common feature of this wide-ranging group was their experience as intermediaries who employed Spanish and the indigenous languages to establish contact within the Spanish and the local communities in civil and ecclesiastical spheres.”

“The local officials are mortal enemies of the head chiefs because they have to defend the Indian. And so they make sure that they all die hung. And the said corregidor has him hung or punished, in public, to the contentment of the local official and the father of the doctrine, as they hung don Juan Cayan Chire, head chief, and don Pedro Poma Songo of Luri Cocha, who died while retreating. Don Diego Tiracina de Banbo who died retreating. And don Cristóbal de León was taken and punished.”

5. The Father or the Master of Doctrine, Learning Obstacles?

“Those magistrates and fathers and local officials deeply hate the Ladino Indians who know how to read and write, and even more so if they know how to draw up petitions, because they are not interrogated about all the aggravation and upset and damage. And if they can, they will banish them from this people in this kingdom.”

“The fathers of the doctrines cruelly punish the children. Although it is ordered in the rules of don Francisco de Toledo, Viceroy, and confirmed by His Majesty and the Holy Concilium, the boys of five years enter the doctrine and at seven years leave for the communities.”

“(…) Throughout the year, the boys of that school were neither taught the doctrine nor knew nothing of it. They were drunk every day, lost and crying, earning wages to the pleasure of the father at the cost of the Indians.”

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adorno, Rolena. 1984. Paradigmas perdidos: Guamán Poma examina la sociedad española colonial. Revista Chungará 13: 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Rolena. 1991a. Nosotros somos los kurakakuna. Imágenes de Indios Ladinos. In Transatlantic Encounters. Edited by Kenneth J. Andrien and Rolena Adorno. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 232–72. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Rolena. 1991b. La visión del visitador y el indio ladino. In Cultures et sociétés Andes et Méso-Amérique Mélanges en hommage à Pierre Duviols. Edited by Raquel Thiercelin. Aix-en-Provence: Université de Provence, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Rolena. 1991c. Guamán Poma. Literatura de resistencia en el Perú colonial. Mexico: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Rolena. 1992. El indio ladino en el Perú colonial. In De palabra y obra en el Nuevo Mundo. Edited by Miguel León-Portilla. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno, pp. 369–95. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Rolena. 2000. Contenidos y contradicciones: La obra de Felipe Guamán Poma y las aseveraciones acerca de Blas Valera. Ciberletras: Revista de crítica literaria y de cultura 2. Available online: http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v01n02/Adorno.htm (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Adorno, Rolena, and Iván Boserup. 2003. New Studies of the Autograph Manuscript of Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum. [Google Scholar]

- Alaperrine-Bouyer, Monique. 2007. La educación de las elites indígenas en el Perú colonial. Lima: Institut français d’études andines, Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Instituto Riva-Agüero. [Google Scholar]

- Alciato, Andrea. 1531. Emblematum liber. Augsburg: Steyner. [Google Scholar]

- Cantù, Francesca. 2001. Guamán Poma y Blas Valera. Tradición Andina e Historia Colonial. Roma: Antonio Pellicani Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, José. 1997. Escribir es nunca acabar: Una aproximación a la conciencia metalingüística de Don Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala. Lexis 21: 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 2006. Cuzco: La piedra donde se posó la lechuza. Historia de un nombre. Lexis 30: 143–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 2010. El contacto inicial quecha-castellano: La conquista del Perú con dos palabras. Lexis 34: 369–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chang-Rodríguez, Raquel. 2005. La palabra y la pluma en ‘Primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno’. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro, César. 2008. Emblemática y Arte de la Memoria en el Nuevo Mundo: El testimonio de Guamán Poma de Ayala. In Imagen y Cultura. La interpretación de las imágenes como Historia Cultural. Edited by Rafael García Mohíques and Vicent Francesc Zuriaga Senent. Gandía: Generalitat Valenciana, pp. 423–39. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, John. 2004. Hacen muy diverso sentido: Polémicas en torno a los catequistas andinos en el virreinato peruano (siglos XVI-XVII). Histórica 28: 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Curátola, Marco. 2003. El códice ilustrado (1615/1616) de Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala: Hacia una nueva era de lectura. Colonial Latin American Review 12: 251–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dueñas, Alcira. 2008. Fronteras culturales difusas: Autonomía étnica e identidad en textos andinos del siglo XVII. Bulletin de l’Institut Francais d’Études Andines 37: 187–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescano, Enrique. 2002. Sahagún y el nacimiento de la crónica mestiza. Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad 23: 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, Sabine. 2005. Guamán Poma de Ayala como traductor indígena de textos culturales: La Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno (c. 1615). Fronteras de la Historia 10: 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galino Carrillo, Mª Ángeles. 1948. Los tratados sobre educación de príncipes (siglos XVI y XVII). Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- Garatea, Carlos. 2016. ¿Diálogo o mímesis? A propósito de textos coloniales y Guamán Poma de Ayala. Cuadernos de la Asociación de Lingüística y Filología de América Latina 8: 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- González Boixo, José Carlos. 1999. Hacia una definición de las crónicas de Indias. Anales de Literatura Hispanoamericana 28: 227–37. [Google Scholar]

- González Vargas, Carlos, Hugo Rosati Aguirre, and Francisco Sánchez Cabello. 2001. Sinopsis del estudio de la iconografía de la Nueva corónica y buen gobierno escrita por Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala. Historia 34: 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- González Vargas, Carlos, Hugo Rosati Aguirre, and Francisco Sánchez Cabello. 2003. Guamán Poma. Testigo del mundo andino. Santiago de Chile: LOM Ediciones- Centro de Investigaciones Barros Arana. [Google Scholar]

- López-Baralt, Mercedes. 1988. Icono y conquista: Guamán Poma de Ayala. Madrid: Hiperión. [Google Scholar]

- López-Baralt, Mercedes. 1990. La iconografía política del Nuevo Mundo: El mito fundacional en las imágenes católica, protestante y nativa. In La iconografía política del Nuevo Mundo. Edited by Mercedes López-Baralt. Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico, pp. 51–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, Christopher H. 1995. La vida cotidiana y la dualidad ladino-indígena. In Historia General de Guatemala. Siglo XVIII hasta la Independencia. Edited by Jorge Luján Muñoz and Cristina Zilbermann de Luján. Guatemala: Asociación de Amigos del País-Fundación para la Cultura y el Desarrollo, pp. 211–24. [Google Scholar]

- Murra, John V., and Adorno Rolena. 1980. El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno de Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala. Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Murúa, Fray Martín de. 2004. Códice-Murúa-Historia y Genealogía de los Reyes Incas del Perú del Padre Mercedario Fray Martín de Murúa (Códice Galvin). Edited by Juan Ossio. Madrid: Testimonio Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Gala, Rosario. 2003. Lengua y Cultura en la ‘Nueva Corónica y buen Gobierno’. Aproximación al Español de los Indígenas en el Perú de los siglos XVI y XVII. Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, Julio. 1988. El cronista indio Guamán Poma de Ayala y la conciencia cultural pluralista en el Perú colonial. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 36: 365–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2009a. Palabra, Imagen y Símbolo en el Nuevo Mundo: De las imágenes memorativas de fr. Diego Valadés (1579) a la emblemática política de Guamán Poma de Ayala (1615). Nova Tellus. Anuario del Centro de Estudios Clásicos 27: 19–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2009b. Retórica, naturaleza y cultura en Indias: La atención al otro desde Bartolomé de las Casas hasta fr. Diego Valadés. Uku Pacha 13: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2010. La Primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno de Guamán Poma de Ayala (1615–1616): Un estudio desde la emblemática política europea y la topología andina. In Dulces Camenae. Poética y Poesía Latinas. Edited by Jesús Luque, Mª Dolores Rincón and Isabel Velázquez. Jaén-Granada: Universidad de Granada, pp. 629–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2011a. Sociedad, Política y Religión en el Virreinato del Perú. La Subversión del Orden Colonial en la ‘Primer Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno’ (1615–1616) de Guamán Poma de Ayala. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

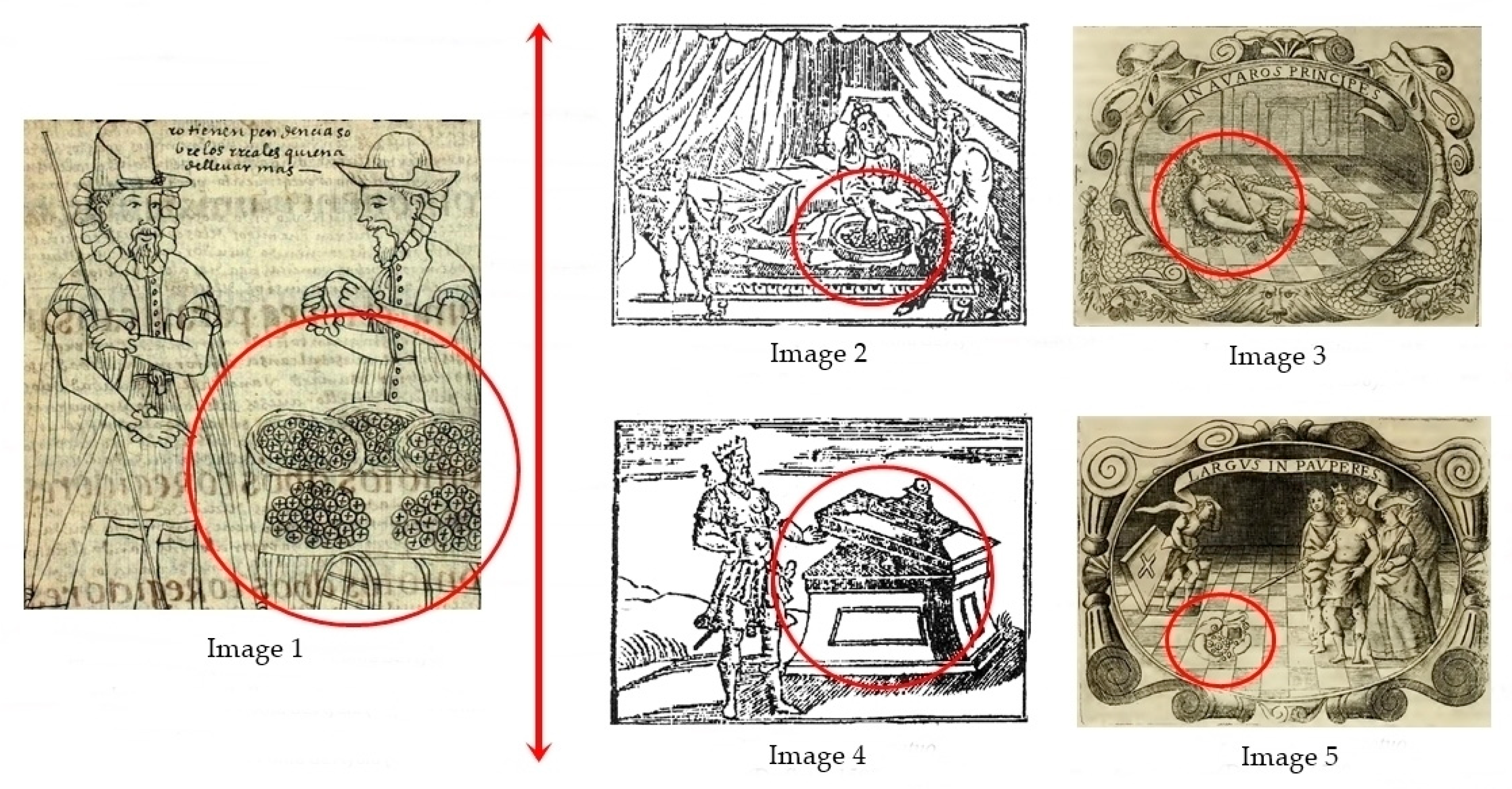

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2011b. El indio ladino en la emblemática política de la Primer nueua corónica y buen gobierno (1615–1616): El caso de don Cristóbal de León. In Emblemática Trascendente: Hermenéutica de la Imagen, Iconología del Texto. Edited by Rafael Zafra and José Javier Azanza. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra, pp. 595–606. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2011c. Retórica y Predicación en el Nuevo Mundo: Palabra e Imagen. Los Testimonios de Fray Diego Valadés y Guamán Poma de Ayala. Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2013. La Pedagogía de la Evangelización Franciscana en el Virreinato de Nueva España (Siglo XVI). Zaragoza: Libros Pórtico. [Google Scholar]

- Ossio, Juan. 1998. Historia y Genealogía de los Reyes Incas del Perú del Padre Mercenario. Madrid: Testimonio Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Parodi, Claudia, and Marta Luján. 2014. El español de América a la luz de sus contactos con el mundo indígena y el europeo. Lexis: Revista de lingüística y literatura 38: 377–99. [Google Scholar]

- Perceval, José María. 2003. Opinión Pública y Publicidad (siglo XVII). Nacimiento de los Espacios de Comunicación Pública en Torno a las Bodas Reales de 1615 Entre Borbones y Habsburgo. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cantó, María Pilar. 1996. El buen Gobierno de Don Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala. Cayambe: Abya-Yala. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzuto, Marcela. 2006. Una lectura de la tradición humanista en el discurso de Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno de Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala. Moenia 12: 225–41. [Google Scholar]

- Poma de Ayala, Felipe Guamán. ca. 1616. Primer Nueua Corónica y Buen Gobierno. Copenhagen: Royal Library of Denmark.

- Porras Barrenechea, Raúl. 1999. Obras Completas de Raúl Barrenechea, I. Indagaciones Peruanas. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos-Fondo Editorial e Instituto Raúl Porras Barreneachea. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de la Flor, Fernando. 2000. La sombra del Eclesiastés es alargada: Vanitas y deconstrucción de la idea de mundo en la emblemática española hacia 1580. In Emblemata Aurea. La emblemática en el Arte y la Literatura del Siglo de Oro. Edited by Rafael Zafra and José Javier Azanza. Madrid: Akal, pp. 337–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián, Santiago. 1995. Emblemática e Historia del Arte. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Serna, Mercedes. 2012. La política colonial en las obras del Inca Garcilaso de la Vega y de Guamán Poma de Ayala. Anales de Literatura Hispanoamericana 41: 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano, Juan de. 1653. Emblemata Regio Politica in Centuriam Unam Redacta et Comentariis Ilustrata. Madrid: Domingo García Morrás. [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, Hernando. 1599. Emblemas Moralizadas. Madrid: Herederos de Juan Iñiguez de Lequerica. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Guchte, Maarten. 1992. Invention and assimilation: European Engravings as models for the drawings of Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala. In Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author. Edited by Rolena Adorno, Mercedes López-Baralt, Tom Cummins, Jhon V. Murra, Teres Gisbert and Maarten van de Guchte. New York: American Society/Art Gallery, pp. 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Velezmoro, Víctor. 2005. Una mirada a las acuarelas del manuscrito Murúa 1590 y su relación con el arte de Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala. BIRA 32: 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Véliz Cartagena, Mauricio. 2008. Un lugar en el mundo: Palabras, saberes musicales e identidad en el Perú del siglo XVII. Histórica 32: 77–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel, Nathan, ed. 1973. Pensamiento salvaje y aculturación. In Sociedad e Ideología. Ensayos de Historia y Antropología Andinas. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, pp. 165–228. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This pragmatic materialization of the combined use of text and image was noted in the numerous symbolic programs of mural painting and on canvas, triumphal carriages, and tumultuous funerals in both New Spain and colonial Peru (Ortega-Sánchez 2011c). |

| 2 | Proven the original page numbering of the chronicle, in this investigation, the standardized version of Murra and Adorno (1980) was used. |

| 3 | Going by news from the chronicler, his father had lent service to this captain in Huarinapampa (Collao), on which occasion he had saved the life of the captain. In gratitude, the Spanish would grant him the title ‘de Ayala’. |

| 4 | In 1616, the chronicler incorporated additions and amendments to the first version of the manuscript, the reason for which this date may be proposed as the most likely for the final edition of the work (Adorno and Boserup 2003, pp. 48–49). On the controversial nature of the chronicle, see the studies of Adorno (2000) y Cantù (2001). |

| 5 | Cod. GKS 2232 4°, Royal Library of Denmark, Copenhagen. |

| 6 | Among the remedies to the disorder of the colonial administration is the proposal of author: There should be two Royal delegates, the Viceroy and the Royal Counsel; each province should be administered by a native chief; the natural privilege of the elders should be acknowledged; the ordainment of native priests will be permitted; indigenous and Spanish will have to separate into different villages, avoiding mixing their race and its effects on the racial, ethnic, and social composition of Andean Peru, origin of the dismantlement of traditional hierarchies, and encouraging the repopulation of the indigenous communities; the rape of Indian women by priests will be prohibited; and a visitor general will be appointed, with responsibility for controlling the system (Ortega-Sánchez 2011a). |

| 7 | The literature de regimine principum, identified as a genre in the 16th century, was characterized by the personal attitude with which the writers–illustrators addressed the governors—sources of both good and evil of the kingdoms—because of the emphasis on education and on the necessary representation of the principle as the model of virtue (Galino Carrillo 1948). It is precisely the illustrated classification of topoi, vices and virtues, that models the genre in manuals, phrase books and illustrated collections of everyday places (Chaparro 2008). |

| 8 | Of particular importance for our author is the Tercero Catecismo y exposición de la doctrina por sermones (Third Catechism and exposition of the doctrine for sermons), in which the Jesuit, José de Acosta, would participate in a very active manner, and whose word-by-word recommendations were: adaptation of the text to the different publics, use of repetitions for the fixation of the message in the memory, and use of a clear style or conversational tone (Ortega-Sánchez 2009b). |

| 9 | Proof of which is the important confusion between two facts: the astonishment of the conqueror, Pedro de Candía, gazing at the wealth of Huayna Cápac in Tumbes during the expedition of 1527, a documented event, and the supposed occasion of a meeting between both in Cuzco (Poma de Ayala ca. 1616, p. 371). |

| 10 | This fanciful linguistic confusion, however, appears not to link up with the true intention of the chronicler, who develops a metalinguistic awareness. We coincide with Cárdenas (1997) in considering this conscience as the capacity to “perceive, on the one hand, certain morphosyntactic features of monolinguist speakers of Castilian and bilingual speakers with a more accentuated degrees of bilingualism than the former; [and] on the other hand, (…) [to distinguish] different grades of competence among Quechua speakers and foreign speakers. This perception is the one that allows them to reproduce them, to play with them and to find an effect of true similarity that is exploited for its own ends of resistance and protest” (Cárdenas 1997, p. 55). As a consequence of the influence of the culturally dominant social language, one of the reflections of linguistic reality was the appearance of more recognizable varieties in the colonial context: the transposition of structures proper to Castilian, criticized by the chronicler (Cerrón-Palomino 2010). The metaliguistic awareness of Guamán is also translated into competency capable of “controlling the intrusions that happen with bilingualism”, “to resort to their mother tongue when the narration so demands and (…) to alternate registers and linguistic levels (…), in other words, to adapt discursive and textual structures in Spanish to speak about the Andean world, without losing touch with their Andean identity” (Garatea 2016, p. 52). |

| 11 | The author affirms the existence of a stage of pre-Hispanic, pre-evangelization led by the apostle Saint Bartholomew. It is in this period, approached in the narration of the four pre-Inca ages, where Guamán attributes the order and the assumption of Christian values to Andean society: “(…) And the Holy Spirit was sent to the holy apostles and the apostles shared with the whole world. And here came Saint Bartholomew to this kingdom of the Indies in this time of Chinbo Urma (second reign, coya)” (Poma de Ayala ca. 1616, p. 123). |

| 12 | The idea of an illustrated chronicle appears to be motivated by the known affection of the monarch for the visual arts: “I have worked hard to produce, with the desire of presenting to your Majesty, this book entitled Primer nueua corónica on the Indies of Peru and worthy of the said Christian faithful, written and sketched with my hand and ingenuity so that the variety of them [the images] and of the colours and the invention and the design to which your Majesty is disposed will lighten the weight and irritation of a reading lacking invention and ornament as well as the polished style found in the great classics” (Poma de Ayala ca. 1616, p. 10). |

| 13 | The formal iconographic correspondences and the content of Historia y genealogía real de los Reyes Incas del Perú. De sus hechos. costumbres, trajes y manera de gobierno, o Códice Murúa, de Fray Martín de Murúa (Curátola 2003; Murúa 2004, pp. 7–72; Velezmoro 2005). |

| 14 | The cintas parlantes or descriptive phrases, already frequent in the artistic expression of Medieval Europe, name and dramatize the scene, contributing a narrative to the image on which they appear. They can be turned into a true dialogue between the characters that are acted out. |

| 15 | The interpretation of the meaning of the vocable Cuzco as “belly-button of the world” appears to respond to a literary topos, often turned to by renaissance authors and recovered by the Inca Garcilaso in this Commentaries (II, XI, 89): “The place as a point or a centre [of the Tauantinsuyu] the city of Cuzco, which in that particular Inca dialect means the belly-button of the world: they called it a belly-button quite rightly, because Peru is very lengthy and narrow like a human body, and that city is almost in the middle (our italics)” (Cerrón-Palomino 2006, p. 156). |

| 16 | In the use of his mind and, therefore, capable of detecting idolatries, associated objects and ancestral rituals, and as the interaction between the Andean and Spanish cosmovisions advanced, the presence of the Ladino Indian as a character type in colonial society was enshrined in the acceptance of various roles: Messianic leaders, litigants, officials of Church and State, writers, and companions of ecclesiastic visitors. Guamán was found among these ‘Indians of trust’, as he declared when he recalled his father Cristóbal de Albornoz, judge and ecclesiastical visitor, on the subject of the extirpation of the idolatry in the expressions of the Taqui Onqoy (‘illness of the dance’) between the years 1569 and 1571 in Huamanga. Active participation in colonial administration and politics led the Andean to define himself as Catholic throughout the rest of his work, his status remaining the same as his ancestors. On this point, see Adorno (1991a, 1991b). |

| 17 | The etymology of his name and surname have led to reflection among scholars of the life experience of the chronicler and in the connection of the cultural cosmovisions, the west and the Andean: ‘Cristóbal’ (server of Christ) of ‘León’ (servant of Lion, puma). |

| 18 | The reasons for the criticism could lie in the direct contacts of the Ladino Indian with the indigenous population, on occasions, directed at “belittling, mistreating, robbing and defrauding the Indian” (Lutz 1995, p. 222). |

| 19 | For Guamán, nudity without genitals expresses vulnerability, innocence, primigenial morality. Adam and Eve are represented in that way in “God created the world and delivered it unto Adam and Eve” (Poma de Ayala ca. 1616, p. 12). And he repeated as much when denouncing Spanish and Inca abuses. If, by contrast, the sexual organs were represented and, in a disproportionate way, in the carvings of the natives, the idea transmitted referred to ‘complicity’ with the corruption of the colonies in the Indies. In the case of the male Indians, it implied a relation of vulnerability towards the Spanish outrages (Ortega-Sánchez 2011a). |

| 20 | On the music and its role in shaping identities in the Viceroyalty of Peru, consult the study of Véliz Cartagena (2008). |

| Topological Category of Reading | Key to Narrative–Iconographic Interpretation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of reading Scenographic narratio | Central iconographic space Invert the reader–observer position | The direction of the iconographic reading starts at a central space, in accordance with the scenographic narratio, the inverse of the position of reader–observer. |

Symbolic right–left relation | Right (high values, good ethics, generally positive ethical scores) Left (conceptual opposites) | In the symbolic right–left relation, the high values and ethical virtues are awarded to the right space, while their conceptual opposites, pictorial motifs confronting the definition of such high values, to the left. |

Symbolic male–female behavior | Male (right) Female (left) | In the symbolic masculine–feminine relation, the topological correspondence of the first will be towards the right, while the topology of the second will be governed by the symbolic space of the left. |

Hanan–Hurin Relation | Hanan (up) Hurin (down) | The topological values of the Hanan correspond to the position of “upwards”. In the Hanan is found the Chinchaysuyu, the richest and most virtuous suyu or pathway of the Tawantinsuyu, from whom Guamán states his descendance. The topological values of the Hurin, in turn, correspond to the position “downwards”. In the Hurin, we can find the Collasuyu, known, as the Chronicler tells us, for its hypocritical and covetous nature, illustrated by the exploitation of the mines of Potosí. |

| Counter value of the vertical hierarchy. Counter value of horizontal right–left hierarchy. | Vertical inverted hierarchical relation Investment of the right–left relation | When the author protests about certain events or customs, the vertical–hierarchical relation appears intentionally reversed. This contrary attitude would be the expression of chaos. If with the hierarchy of security, the authority or standing of the individual or group of individuals is placed in a contrary position, then likewise, security in the right–left relations reinforces the idea of disorder or superimposition of the Collaysuyu on the Chinchaysuyu—the ‘world upside-down’. |

| Regulating motive right–left | Regulation and synthesis | The regulatory reason can be found in some right–left relations, by which the relation between those self-excluding extremes is measured by a regulatory element, placed center stage. The importance of its function is rooted, either in its capacity to conciliate the difference, integrating it into a harmonious whole, or to synthesize the opposing pairs that were surrounding it. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-González, C.; Ortega-Sánchez, D. The Pedagogy of the Evangelization, Latinity, and the Construction of Cultural Identities in the Emblematic Politics of Guamán Poma de Ayala. Religions 2019, 10, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070441

Pérez-González C, Ortega-Sánchez D. The Pedagogy of the Evangelization, Latinity, and the Construction of Cultural Identities in the Emblematic Politics of Guamán Poma de Ayala. Religions. 2019; 10(7):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070441

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-González, Carlos, and Delfín Ortega-Sánchez. 2019. "The Pedagogy of the Evangelization, Latinity, and the Construction of Cultural Identities in the Emblematic Politics of Guamán Poma de Ayala" Religions 10, no. 7: 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070441

APA StylePérez-González, C., & Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2019). The Pedagogy of the Evangelization, Latinity, and the Construction of Cultural Identities in the Emblematic Politics of Guamán Poma de Ayala. Religions, 10(7), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070441