The Uses of Human Malleability: Images of Hellish and Heavenly Sojourns in Pre-Modern Burma

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Visuality: Saṃvega, Pasāda, and Malleability

3. The Uses of Fear

4. Interiorities

5. The Dhamma as a Societal Ideology

6. The Reconstitution of the Conditioning Mechanism in the Late Premodern Period

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources

Anderson, Carol S. 2012. What do We See through the Dhamma Eye. In Embedded Languages: Studies of Sri Lankan and Buddhist Cultures. Edited by Anderson. Colombo: Sri Lanka, Godage International Publishers, pp. 151–92.Anonymous. 2016. Pathamasambodhi, The Life of the Lord Buddha. Bangkok: Wat PhrachetuphonBodhi, Bhikkhu. 1993. Questions of King Milinda: An Abridgement of the Milindapanha. Translated by N. K. G. Mendis. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 2000. Samyutta Nikaya, the Connected Discourses of the Buddha. 2 vols. Somerville: Wisdom Publications.Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 2012. Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Anguttara Nikaya. Somerville: Wisdom Publication.Bullis, Douglas. 1999. Mahanamasthavira, the Mahavamsa. Fremont: Jain Publishing Co.Burlingame, Eugene Watson. 1921. Buddhist Legends Translated from the Original Pali Text of the Dhammapada Commentary. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Collins, Steven. 1993. The story of the elder Maleyyadeva. Journal of the Pali Text Society 18: 65–77.Cowell, Edward B. 1994. Jatakas. 6 vols. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.Davids, T. W. Rhys. 1890. Questions of King Milinda. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.De Silva, Padmasiri. 2007. Theoretical perspectives on emotions in early Buddhism. In Jayatilleke Commemoration Lecture, 1976. Colombo: Sri Lanka, n.p.Hazelwood, Ann Appleby. 1983. Saddhammopayana. Master’s thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.Hazelwood, Ann Appleby. 1987. Pancagatidipani. Journal of the Pali Text Society 11: 131–58.Horner, Iseline B. 1963–1964. Milindapanha. 2 vols. London: Luzac.Jayawickrama, Nidana A. 2000. Story of Gotama Buddha Jataka Nidana. Oxford: Pali Text Society.Masefield, Peter. 2000. The Itivuttaka. Oxford: Pali Text Society.Law, Bhimala C. 1923. The Buddhist Conception of Spirits. Calcutta: Thacker, Spin and Co.Nanamoli, Bhikkhu, and Bhikkhu Bodhi. 1995. Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Somerville: Wisdom Publications.Nanamoli, Bhikkhu. 1999. Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosa. In The Path of Purification. Seattle: BPS Pariyatti Edition.Olivelle, Patrick. 2008. Life of the Buddha by Asvaghosa. New York: New York University Press.Shaw, Sarah. 2006. THE JATAKAS: Birth Stories of the Bodhisatta. London: Penguin.Thanissaro, Bhikkhu. 1997. Affirming the Truths of the Heart: Buddhist Teachings on Samvega and Pasada. Dhammatalks.org. Available online: https://www.dhammatalks.org/books/NobleStrategy/Section0004.html (accessed on 6 May 2020).Trenckner, Carl Wilhelm, ed. 1880. The Milindapanho, Being Dialogues between King Milinda and the Buddhist Sage Nagasena. London: Williams and Norgate.Walshe, Maurice, and Venerable Sumedho Thera. 1995. The Long Discourses of the Buddha, a Translation of the Digha Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications.Wilson, Liz. 1996. Charming Cadavers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Woodward, Frank Lee, and Edward M. Hare. 2008. Book of Gradual Sayings: Anguttara Nikaya, or More-Numbered Suttas. 5 vols. Oxford: Pali Text Society.Secondary Sources

- Barro, Robert, and Rachel Cleary. 2019. The Wealth of Religions: The Political Economy of Believing and Belonging. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, Anne. 1998. Looking for the Vinaya: Monastic Discipline in the Practical Canon of the Theravada. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 22: 255–85. [Google Scholar]

- Braarvig, Jens. 2009. The Buddhist hell, an early instance of an idea? Numen 56: 254–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, Bonnie. 1995. Thai Tellings of Phra Malai: Texts and Rituals Concerning a Popular Buddhist Saint. Tempe: Arizona State University. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, Michael W. 2006. Powerful Learning: Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma’s Last Dynasty. 1752–1885. Ann Arbor: Centers for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Steven. 1998. Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. 1943. Samvega, aesthetic shock. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 7: 174–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, Kate. 2006. A Theravada code of conduct for good Buddhists. Journal of the American Oriental Society 126: 177–87. [Google Scholar]

- De La Perriere, Benedicte Brac. 2009. An overview of the field of religion in Burmese studies. Asian Ethnology 68: 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, Padmasiri. 2018. The Psychology of Emotions and Humor in Buddhism. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Druzin, Bryan, and Anthony S. Wan. 2015. The Theatre of Punishment: Case Studies in the Political Function of Corporal and Capital Punishment. Washington University Global Studies Law Review 14: 357–99. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Lawrence G. 1989. Was Art Really the Book of the Illiterate? Word and Image 5: 227–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrey, Patricia B., and Peter N. Gregory. 1993. Religion and Society in Tang and Sung China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eckel, David M. 2008. Bhaviveka and His Buddhist Opponents. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton, Samuel Y. 1985. Pictures and Punishment: Art and Criminal Prosecution during the Florentine Renaissance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 2008. Discipline and Punish. Translated by Alan Sheridan. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frasch, Tilman. 1996. Pagan, Stadt und Staat. Stuttgart: F. Steiner. [Google Scholar]

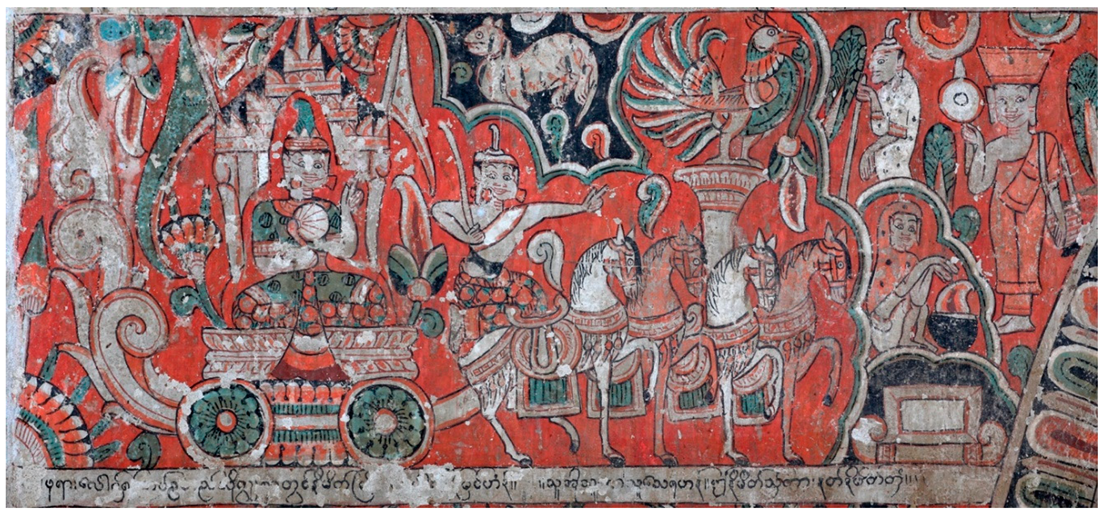

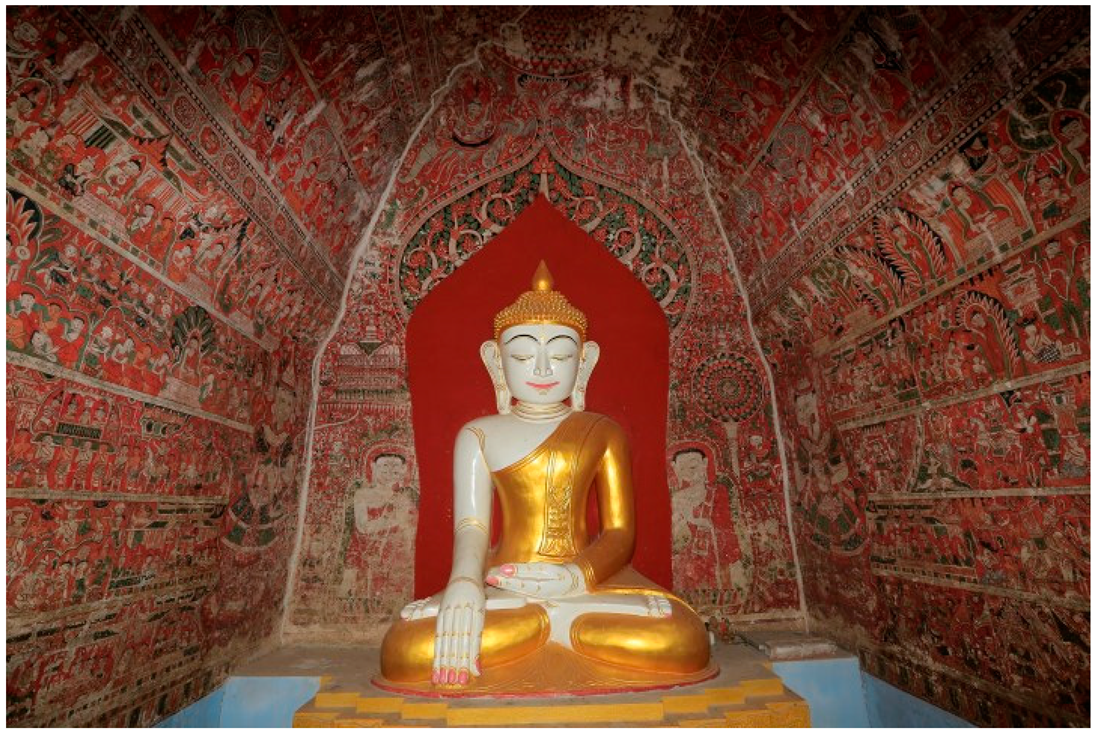

- Gaillard Munier, Cristophe. 2007. Burmese Buddhist Murals. Epigraphic Corpus of the Powin Taung Caves. Bangkok: White Lotus. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard Munier, Cristophe. 2019. Depictions of Portuguese in the Buddhist Murals of Myanmar. Orientations 50: 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Eileen, ed. 2012. Buddhist Hell: Visions, Tours and Descriptions of the Infernal Netherworld. New York: Ithaca Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giustarini, Giuliano. 2012. The role of fear (bhaya) in the Nikayas and the Abhidhamma. Journal of Indian Philosophy 40: 511–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 2012. After sinning: some thoughts on remorse, responsibility and the remedies for sin in Indian religious traditions. In Sins and Sinners: Perspectives from Asian Religions. Edited by Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara. Ldeiden: Brill, pp. 175–215. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Alexandra. 2018. Buddhist Visual Cultures: Rhetoric and Narrative in Late Burmese Wall Paintings. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallisey, Charles, and Anne Hansen. 1996. Narrative, sub ethics and the moral life, some evidence from Theravada Buddhism. Journal of Religious Ethics 24: 305–27. [Google Scholar]

- Handlin, Lilian. 2017. Hedging Against Lives Uncertainties and the Theravada Label. Journal of Burmese Studies 21: 97–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handlin, Lilian. 2012. The King and His Bhagava. In How Theravada Is Theravada: Exploring Buddhist Identities. Edited by Peter Skilling, Jason A. Carbine, Claudio Cicuzza and Santi Pakdeekham. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, pp. 165–236. [Google Scholar]

- Harre, Rom, ed. 1998. The Social Construction of Emotion. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Elizabeth J. 1990–1994. Violence and Disruption in Society: A Study of the Early Buddhist Texts. Boston: Wheel Publication, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Maria. 2003. The Aesthetics of Excess. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 71: 531–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, Maria. 2012. Shame and Apprehension: Notes on the Moral Value of Hiri and Ottappa. In Embedded Languages: Studies in Religion, Culture and History of Sri Lanka. Edited by Carol Anderson. Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers, pp. 237–60. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, Iseline B. 1966. Earth as Swallower. Artibus Asiae Supplementum 23: 151–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagarabhivamsa, Tipitakadhara. 1986. (1348, Burmese Era). Samvegavatthudipani. Mandalay: Nyunt Sarpay. (In Burmese) [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, Victory. 2016. Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, 1580–1760. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luce, Gordon H. 1959. Old Burma Early Pagan. 3 parts. New York: J. J. Augustine. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. 2002. A Short History of Ethics, 2nd ed. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena. 1937–1938. Dictionary of Pali Proper Names. 2 vols. London: J. Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Merback, Mitchell B. 1998. The Thief, The Cross and the Wheel: Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mingun, Sayadaw. 2008. Great Chronicles of Buddhas. Singapore: Singapore Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozik, Suzanne. 2012. Astonishment: A Study of an Ethically Valorized Emotion in Buddhist Narrative Literature in Embedded Languages: Studies of Sri Lankan and Buddhist Cultures. Edited by Carol S. Anderson. Colombo: Godage International Publishers Ltd., pp. 261–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanaponika, Thera, and Hellmuth Hecker. 1997. The Great Disciples of the Buddha: Their Lives, Their Works, Their Legacy. Boston: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pe Maung Tin, and Gordon H Luce. 1920. The Shwegugyi Inscription, Pagan 1141 AD. Journal of the Burma Research Society 10: 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rhys Davids, Thomas William, and William Stede. 1995. The Pali Text Society’s Pali –English Dictionary. Oxford: Pali Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Roodenburg, Herman, and Pieter Spierenburg. 2004. Social Control in Europe, 1500–1800. Ohio: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeber, Juliane. 2008. Communities of Interpretation in the Study of Religion in Burma. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 39: 255–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Robert C. 1995. The Cross-cultural Comparison of Emotion. In Emotions in Asian Thought. Edited by Joel Marks and Roger T. Ames. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, Joseph T. 2012. Poetic Sequsence as Personal Salvation: Saigyo’s Poems “Upon Seeing Pictures of Hell”. Japanese Language and Literature 46: 2–45. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Trent. 2018. Samvega and Pasada, Dharma Songs in Contemporary Cambodia. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 41: 271–325. [Google Scholar]

- Win, Than Tun. 1992. Pali and Sanskrit Loans in Myanmar Language, Pagan Period. Mater’s Thesis, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Yian, Geok Goh. 2015. Southeast Asian Images of Hells: Transmission and Adaptation. Bulletin de l’Ecole Francaise d’Extreme Orient 101: 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Dhammapada Aṭṭhakathā as the commentary to Dhammapada, Cundasukarika Vatthu verse 15 (Burlingame 1921, vol. 28, p. 225ff). Samvegavatthudipani (Jagarabhivamsa 1986 (1348), In Burmese). On the significance of the distinction between the Pali canon and its actually used parts, see (Blackburn 1998; Collins 1998). Pagan is an excellent site to investigate this distinction. For a different treatment of this article’s subject, see (Yian 2015). |

| 2 | On the broader issues, most recently, see (Schoeber 2008, pp. 255–67; De La Perriere 2009, pp. 185–210). |

| 3 | Samvegavatthudipani (Panatipata, 20, pp. 52–54). |

| 4 | (Anonymous 2016, pp. 124–25, 128). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | See (Barro and Cleary 2019). |

| 8 | (Olivelle 2008, pp. 405–9). |

| 9 | (Jayawickrama 2000, p. 99). |

| 10 | For broader implication of these issues, see (Hallisey and Hansen 1996, pp. 314–16). |

| 11 | On the larger issues involved, see (Duggan 1989). |

| 12 | See (Collins 1998, p. 593). |

| 13 | See (Mrozik 2012, pp. 261–88). |

| 14 | (Woodward and Hare 2008, pp. 124–25). On Kokalika, see (Malalasekera 1937–1938, vol. I, p. 673ff). |

| 15 | (Masefield 2000, p. 26). |

| 16 | See for a general discussion of the problematics of hell, the pioneering article (Braarvig 2009). |

| 17 | (Davids 1890) Rhys Davids, translated. 1890. I:89. |

| 18 | (Nanamoli 1999). Buddhaghosa, The Path of Purification, Visuddhimagga, I:53, 55, 57. |

| 19 | See excellent discussion (Anderson 170ff.) (Masefield 2000, p. 52). |

| 20 | See (Sorensen 2012). |

| 21 | (Bodhi 1993, p. 104). |

| 22 | (Woodward and Hare 2008, 3:156). |

| 23 | (Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995, pp. 253–68). |

| 24 | (Woodward and Hare 2008, I: 123ff). |

| 25 | (Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995, pp. 1029–38). |

| 26 | (Jayawickrama 2000, pp. 78–80; Nanamoli 1999, XIII: 34, 35; Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995, pp. 186, 344; Bodhi 2000, p. 294ff; Coomaraswamy 1943). (Sourced from Connected Discourses on the Aggregates. 78. The Lion. (This is Bodhi 2000). Anguttara Nikaya, the Book of Fours, The Lion—this is Bodhi 2012). See also (Nyanaponika and Hecker 1997). |

| 27 | (Walshe and Thera 1995, pp. 265–66; Jagarabhivamsa 1986). |

| 28 | See (Walker 2018, pp. 271–325). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Mingun Sayadaw 6: 180ff. He links it also to the Udana Atthakatha and the Saratthadipani Tika. |

| 31 | |

| 32 | (Nanamoli 1999) 12:80. I thank Professor Phyllis Granoff for alerting me to this citation, private communication, June 2019. For broader issues regarding the use of emotions, see (Harre 1998; MacIntyre 2002; Solomon 1995). |

| 33 | |

| 34 | |

| 35 | (Bullis 1999, p. 1). |

| 36 | I thank professor Samerchai Pulsawan for directing me to this location. |

| 37 | (Shaw 2006, pp. 55–74; Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995). Majjhima Nikaya IV: Bhayabherava Sutta. pp. 102–7. |

| 38 | (Nanamoli 1999, III: 124, XVII: 243, XXI: 26, 29ff., 61, 69; De Silva 2018, pp. 112, 114; Woodward and Hare 2008, pp. 19, 180ff; Shaw 2006, p. 55; Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995, 102ff). |

| 39 | (Nanamoli 1999, XVII:243; Giustarini 2012). |

| 40 | (Woodward and Hare 2008, II:43ff). |

| 41 | For contextualization of these sentiments in South Asian milieus, see (Granoff 2012, p.180ff; Heim 2012, p. 238). |

| 42 | (Rhys Davids and Stede 1995, p. 628). Woodward and Hare, 5:2-5. (Granoff 2012): 185ff., Shulman: unpublished paper. |

| 43 | (Heim 2012, p. 246ff; Woodward and Hare 2008, I:42:ff, II:125, 126). |

| 44 | (Masefield 2000, p. 34). |

| 45 | (Cowell 1994, 5: 135, 140). Mingun Sayadaw, the Great Chronicle of the Buddha, vol. iv. |

| 46 | (Nanamoli 1999, I:22, 23). |

| 47 | (Nanamoli 1999, XXI: 96). |

| 48 | (Trenckner 1880, p. 205ff). |

| 49 | |

| 50 | (Cowell 1994, vol. 3, pp. 129–30). |

| 51 | (Nanamoli 1999, I: 161, II: 93, XIV: 142). |

| 52 | (Win 1992, p. 74). For other settings with somewhat similar developments, see (Crosby 2006, p. 177ff). |

| 53 | |

| 54 | (Harris 1990–1994, p. 1ff; Horner 1963–1964, p. 1:283ff; Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995, pp. 1016–28). |

| 55 | |

| 56 | (Nanamoli 1999). III: 95cc. |

| 57 | See (Handlin 2012). |

| 58 | Thirimingala Inscription, unpublished, 17 century donative notification. |

| 59 | The term gandhakuti was used by contemporaries during the early centuries of the second millennium. (Pe Maung Tin and Luce 1920, p. 63; Win 1992, p. 17). |

| 60 | The structure was found much damaged, and the archaeological department reconstruction record does not reveal where the plaques might originally have been situated. Perhaps the restorers were right to assume that they preceded the plaques narrating the bodhisatta lives, and were placed either in the lowest tiers of the stupa’s outer side, or close to the main entrance. See (Luce 1959, p. I: 262–67). |

| 61 | (Woodward and Hare 2008, p. II: 245ff). |

| 62 | |

| 63 | |

| 64 | |

| 65 | Unpublished lithographic inscription of the history of Shwe Mar Thae Pagoda. This dates to the reign of king Bagyidaw. |

| 66 | (Handlin 2012). |

| 67 | One of the Vimana stories illustrated in late 11th and 12th century Pagan structures, like the Alopyie Gu and the Myinkaba Kubyaukgyi, revolved around a person’s saddha that determined their behavior and its reward, explicitly inscribing the term. |

| 68 | |

| 69 | (Nanamoli 1999, p. XIX: 4; Gardiner 2012, pp. 9, 19; Eckel 2008). Such calamities lists also featured on donative inscriptions, for example in the unpublished stone inscription of the Shwe Ma Thaw Pagoda. |

| 70 | |

| 71 | (Handlin 2012). Munier Gaillard and Myint Aung p. 331. For broader implications, see (Druzin and Wan 2015). |

| 72 | (Handlin 2017). An early example is the 17th century Thirimingala. |

| 73 | In the Powin Daung context, the reference appears in the Nimi Jataka. Image badly damaged. |

| 74 | For other settings, see (Merback 1998, p. 21). |

| 75 | For comparable developments elsewhere, see (Ebrey and Gregory 1993). Thirimingala inscription, unpublished, is an early example from the 17th century. |

| 76 | For background, see (Charney 2006; Lieberman 2016). For analysis of the imagery and its settings from which this article departs in its interpretation, see (Green 2018). |

| 77 | |

| 78 | For comparable developments elsewhere, see (Roodenburg and Spierenburg 2004). See also for Thai context that by then would have begun to be influential in the Burmese setting (Brereton 1995). For similar components in other circulating texts, see (Hazelwood 1983, pp. 42, 194). Also (Hazelwood 1987, pp. 23, 41, 35, 222). For translation of captions under the Powin Daung cave images, see (Gaillard Munier 2007, p. 331). |

| 79 | See (Horner 1966). |

| 80 | (Nanamoli 1999, I: 22: VII: 59, XXI: 59, XXII: 111-112; Heim 2012, p. 242; Bodhi 2012, pp. 1070, 1230). See also Bhkkhu Bodhi, The Guardians of the World, www.accesstoinsight.org. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Handlin, L. The Uses of Human Malleability: Images of Hellish and Heavenly Sojourns in Pre-Modern Burma. Religions 2020, 11, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050230

Handlin L. The Uses of Human Malleability: Images of Hellish and Heavenly Sojourns in Pre-Modern Burma. Religions. 2020; 11(5):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050230

Chicago/Turabian StyleHandlin, Lilian. 2020. "The Uses of Human Malleability: Images of Hellish and Heavenly Sojourns in Pre-Modern Burma" Religions 11, no. 5: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050230

APA StyleHandlin, L. (2020). The Uses of Human Malleability: Images of Hellish and Heavenly Sojourns in Pre-Modern Burma. Religions, 11(5), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050230