“On Golden Tablets”: The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript as a Self-Referential Icon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Manuscript and Its Background

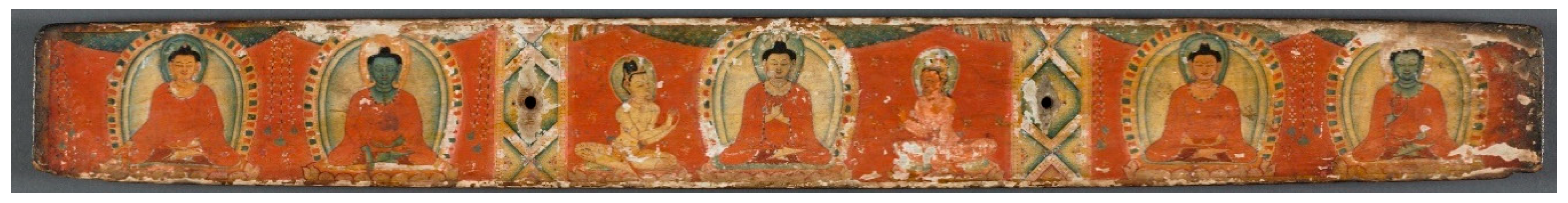

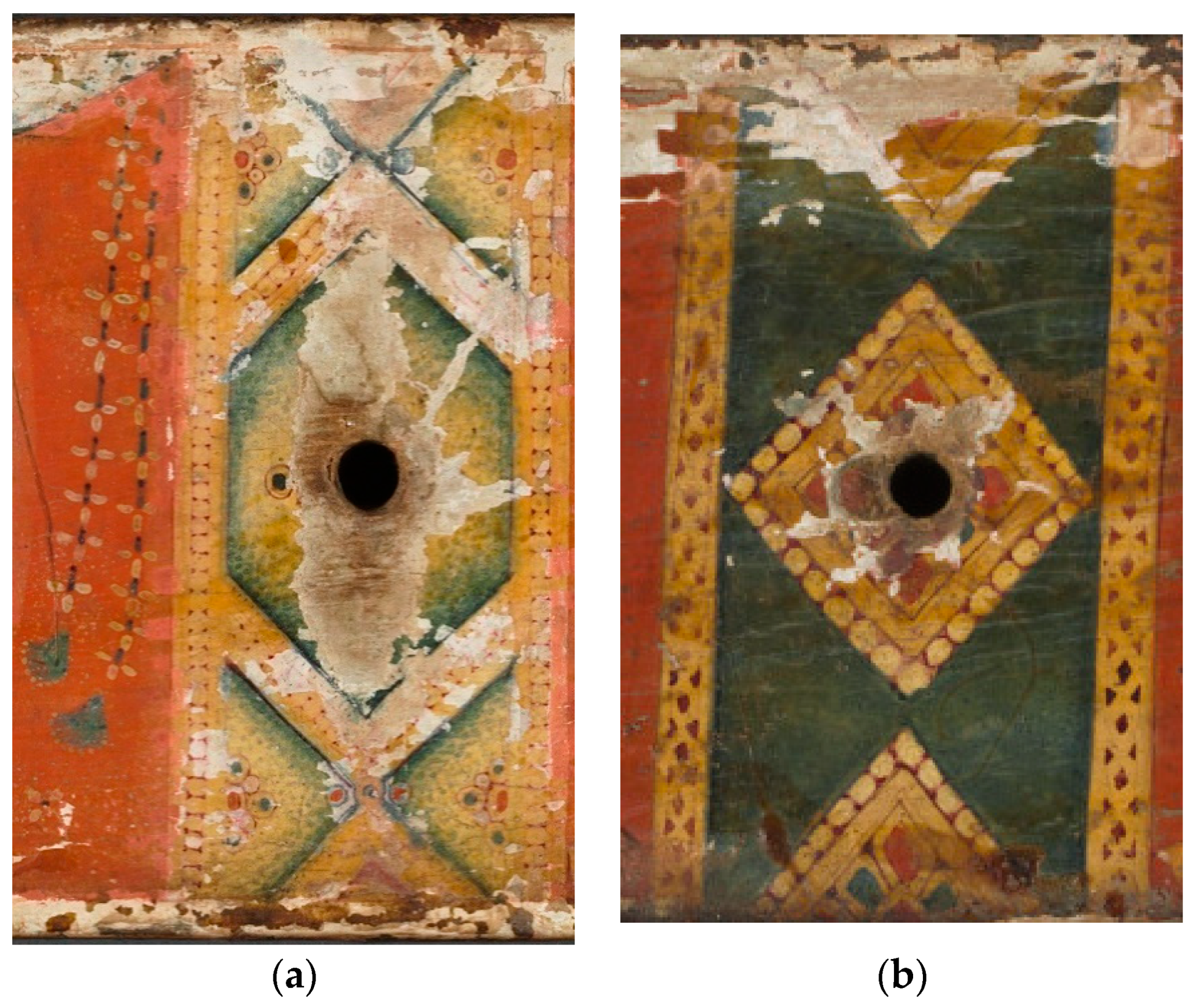

3. The Wooden Covers: A Vertical Axis of Wisdom

4. Materiality as Methodology

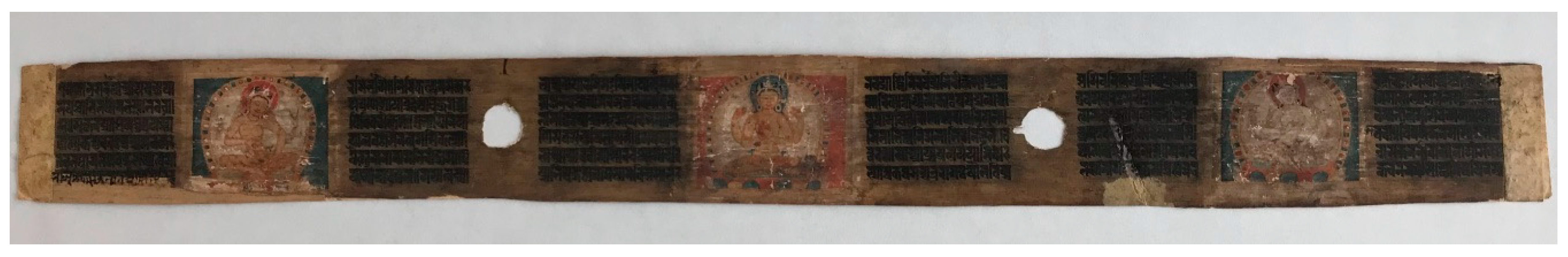

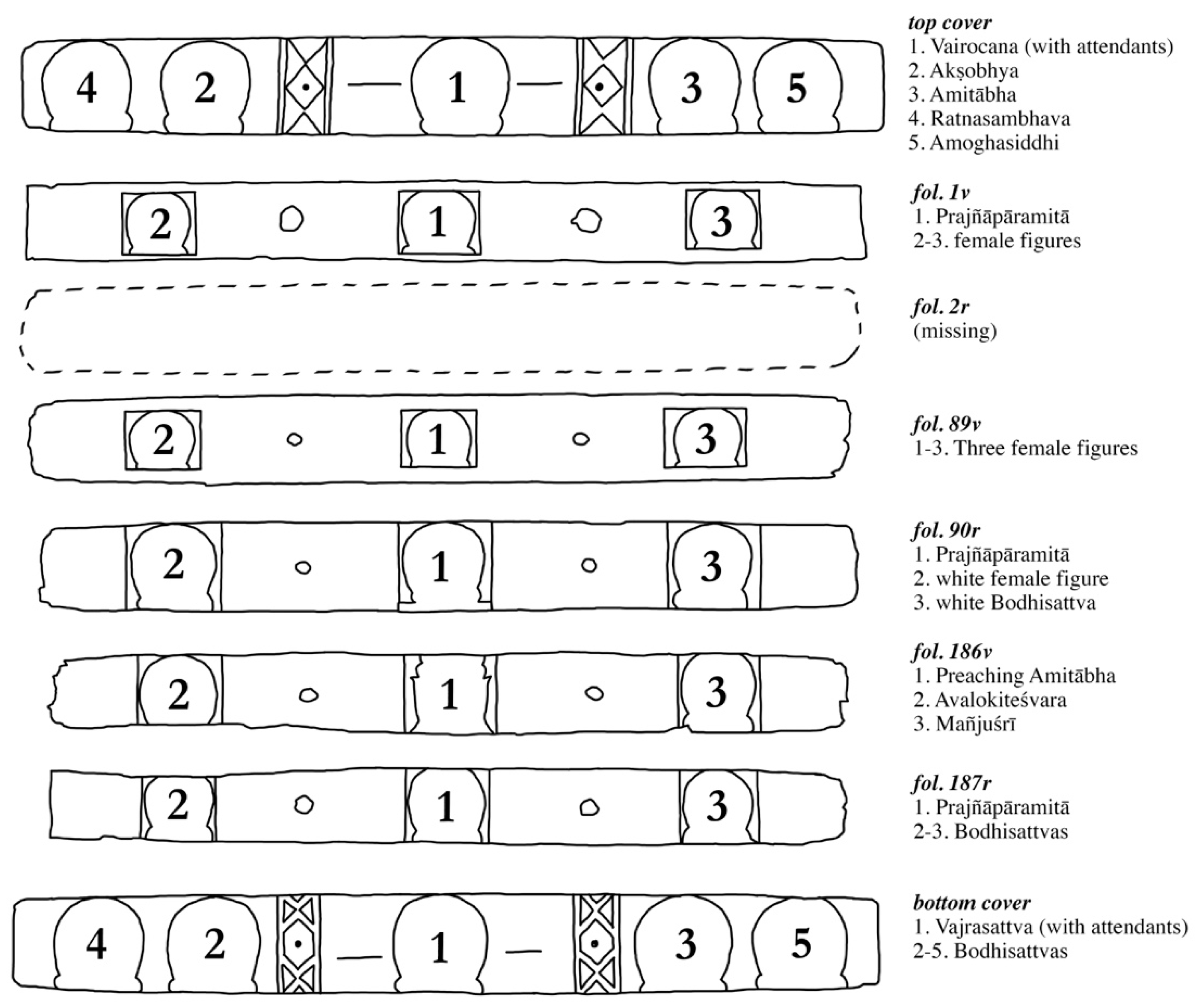

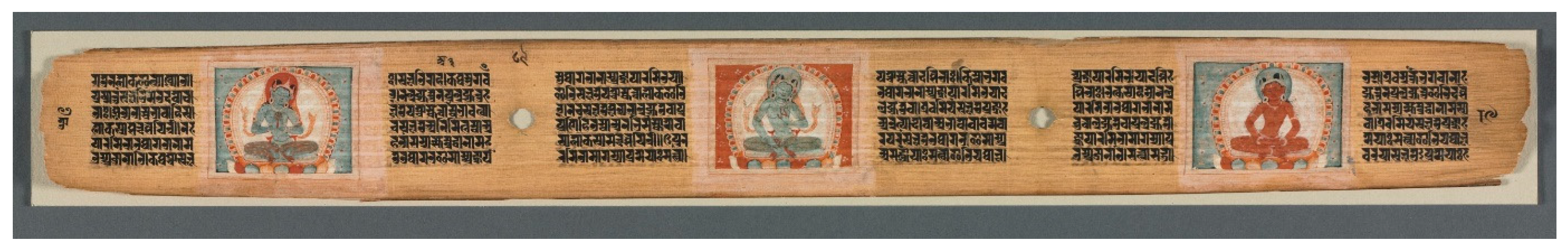

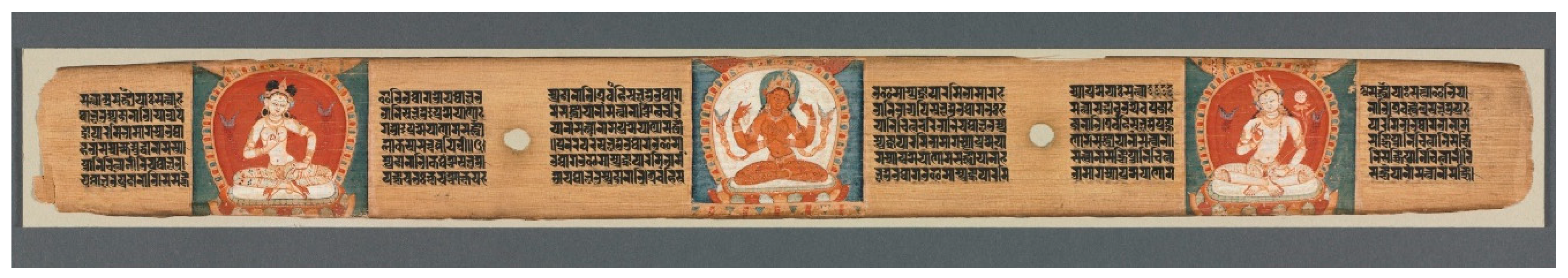

The images serve as indexical signs of the text and provide a visual index for a site map for each book. Through the presence of these images, a book becomes an icon of the text that could help open up the text in one’s mind even when the book is closed. This scheme seems to have become popular from the beginning of the twelfth century, and Nepalese Pañcarakṣā manuscripts follow it most closely. This iconographic trend in its simplistic form subsequently became the most popular method of illustrating a Buddhist manuscript in Nepal. This group would comprise a large number of manuscripts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

5. The Materiality of a Pothi Manuscript

6. The Luxury of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā

Greater would be the merit of someone who would truly believe in this perfection of wisdom; who would, trustingly, confiding in it, resolutely intent on it, serene in his faith, his thoughts raised to enlightenment, in earnest intent, hear it, learn it, bear it in mind, recite and study it, spread, demonstrate, explain, expound and repeat it, illuminate it in detail to others, uncover its meaning, investigate it with his mind; who, using his wisdom to the fullest extent, would thoroughly examine it; who would copy it, and preserve and store away the copy––so that the good dharma might last long, so that the guide of the Buddhas might not be annihilated, so that the good dharma might not disappear […] It would be greater than the merit of one who would completely fill the entire Jambudvipa [the Indian subcontinent] with such Stupas [of the Buddha’s relics]. (emphasis added).

7. Prajñāpāramitā as a Self-Referential Icon

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, Om Prakesh. 1984. Conservation of Manuscripts and Paintings of South-East Asia. London: Butterworths & Co. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Allinger, Eva, and Gudrun Melzer. 2010. A Pañcarakṣā manuscript from Year 39 of the Reign of Rāmapāla. Artibus Asiae 70: 387–414. [Google Scholar]

- Areford, David S. 2012. Reception. Studies in Iconography 33: 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Biernoff, Suzannah. 2012. Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages. New York: Palgrae Macmillian. [Google Scholar]

- Conze, Edward. 1975. The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines and Its Verse Summary, 2nd ed. Bolinas: Four Seasons Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Eimer, Helmut, ed. 1988. Indology and Indo-Tibetology: Thirty Years of Indian and Indo-Tibetan Studies in Bonn. Bonn: Indica et Tibetica Verlag, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsman, Elina. 2018. Phantoms of Emptiness: The Space of the Imaginary in Late Medieval Art. Art History 41: 801–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, Regina, Heinz Mode, and Siegfried Mahn. 1975. Miniaturen, Volks- und Gegenwartskunst Indiens. Leipzig: E.A. Seemann Buch und Kunstverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis, Howard. 1939. A Nepalese Manuscript. Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 26: 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger, Bruce. 2009. Of Pigs and Parchment: Medieval Studies and the Coming of the Animal. PMLA 124: 616–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsinger, Bruce. 2010. Parchment Ethics: A Statement of More Than Modest Concern. New Medieval Literatures 12: 131–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, John C., and Dina Bangdel. 2003. The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art; This Publication Is Issued in Conjunction with the Exhibition The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, Co-Organized by the Columbus Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, October 5–January 11, 2003, February 6–May 9, 2004. Chicago: Serindia Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, Sarah. 2011. Legible Skins: Animal Skins and the Ethics of Medieval Reading. Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval and Cultural Studies 2: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, Sarah. 2017. Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2008. Emptiness on Palm Leaf: A Twelfth-Century Illustrated Manuscript of the “Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā”. Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 82: 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jinah. 2010. A Book of Buddhist Goddesses: Illustrated Manuscripts of the “Pañcarakṣā Sūtra” And Their Ritual Use. Artibus Asiae 70: 259–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2013. Receptacle of the Sacred: Illustrated Manuscripts and the Buddhist Book Cult in South Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2015. Painted Palm-Leaf Manuscripts and the Art of the Book in Medieval South Asia. Archives of Asian Art 65: 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramrisch, Stella. 1964. The Art of Nepal. New York: The Asia Society/Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D. Udaya, G. V. Sreekumar, and U. A. Athvankar. 2009. Traditional writing system in Southern India––Palm leaf manuscripts. Design Thoughts, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sherman E. 1942. Buddhist Art. no. 24. Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sherman E. 1964. A History of Far Eastern Art. New York: H. N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Rob. 2014. Mirror Image: Deity and Donor as Vajrasattva. History of Religions 54: 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Margaret F. 1967. Sculptures from Bihar and Bengal. Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 54: 240–62. [Google Scholar]

- Meahl, Katherine. 2004. Influence néware dans la peinture tibétaine entre le XIe et le XIVe siècle. Dossiers d’Archéologie 293: 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Melzer, Gudrun, and Eva Allinger. 2010. Eine nepalesische Palmblatthandschrift der Aṣṭasahasrikā Prajñāpāramitā aus dem Jahr NS 268 (1148 AD), Teil I. Indo-Asiatische Zeitschrift: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Indo-asiatische Kunst 14: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Melzer, Gudrun, and Eva Allinger. 2012. Die nepalesische Palmblatthandschrift der Aṣṭasahasrikā Prajñāpāramitā aus dem Jahr NS 268 (1148 AD), Teil II. In Berliner Indologische Studien. Published by Klaus Bruhn and Gerd J.R. Mevissen. Berlin: Weidler Buchverlag, vol. 20, pp. 249–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mittman, Asa Simon, and Christine Sciacca. 2017. Robed in Martyrdom: The Flaying of St. Bartholomew in the Laudario of Sant’Agnese. In Flaying in the Pre-Modern World: Practice and Representation. Edited by Larissa Tracy. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 140–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, Pratapaditya. 1978. The Arts of Nepal II.: Painting. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, Pratapaditya. 1985. Art of Nepal: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. Berkeley: Los Angeles County Museum of Art in association with University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Cleveland Museum of Art. 1958. Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- The Cleveland Museum of Art. 1966. Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- The Cleveland Museum of Art. 1969. Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- The Cleveland Museum of Art. 1978. Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, Larissa, ed. 2017. Flaying in the Pre-Modern World: Practice and Representation. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, Yana. 2009. Sacred Leaves: The Conservation and Exhibition of Early Buddhist Manuscripts on Palm Leaves. The Book and Paper Group Annual 28: 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Weissenborn, Karen. 2012. Eine Auflistung illuminierter buddhistischer Sanskrit-Handschriften aus Ostindien. In Berliner Indologische Studien. Published by Klaus Bruhn and Gerd J.R. Mevissen. Berlin: Weidler Buchverlag, vol. 20, pp. 277–320. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The CMA’s manuscript’s images, excluding the first folio, are dealt with by Kim (2015) and Pal (1978, 1985), but little else has been done extensively on the manuscript’s text or images. The manuscript was purchased from the Heeramaneck Galleries in 1938 and is briefly featured in the Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art (March, Hollis 1939; October, Marcus 1967); two texts by Lee (1942, 1964); and The Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art (The Cleveland Museum of Art 1958, 1966, 1969, 1978). The manuscript also makes appearances in (Kramrisch 1964, p. 79; Hickmann et al. 1975; Meahl 2004). It was exhibited at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1942. |

| 2 | A handwritten invocation and three syllables, possibly for consecration, have been written directly behind the painted image of Prajñāpāramitā. |

| 3 | According to the unpublished analysis of Shin’ichirō Hori, the colophon on folio 188r states that the manuscript was made in the year 239 of the Newar Samvat in the month of Āśvina on “the eighth of the light fortnight,” which corresponds to Sunday, September 14, 1119 CE. Shin’ichirō Hori 2017. (International Institute for Buddhist Studies, Tokyo.) Personal communication. The curator in charge of the manuscript in Cleveland, Sonya Rhie Mace, confirmed the reading of the date as 239, instead of 237, by comparison with other examples of the numeral as written throughout the same manuscript. Kim (2015, pp. 57–86) incorrectly dates the CMA’s manuscript to 1114 CE. Furthermore, Phyllis Granoff identified an excerpt from Haribhhadra’s final remarks to his commentary on the Ratnaguṇasaṁcaya-gāthā at the bottom of folio 187v. The Ratnaguṇasaṃcaya is a verse rendering in Prakrit of the core teachings of the Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra. Some manuscripts of the sūtra include the full Ratnaguṇasaṁcaya. In addition to his commentary on the Ratnaguṇasaṃcaya, Haribhadra (c. 800) wrote an erudite commentary on the Aṣṭasāhasrika Prajñāpāramitā itself. Granoff 2019. (Yale University, New Haven, CT.) Personal communication. |

| 4 | Shin’ichirō Hori transliterated and translated the colophon: deyadharmo yaṃ pravaramahāyānayāyinaḥ śrīmannepāladeśīyabhikṣuāryaśrīmittrasya yad=atra puṇyan=ta; ○ d=bhavatv=ācāryopādhyāyamātāpitṛpūrvaṅgamaṅ=kṛtvā sakalasattvarāśer=anuttarajñānaphalāvāptaya iti || || ○ [siddham] samvat* ā la ña aśvaniśuklāṣṭamyāṃ | śrīvikramaśīlamahāvihāre || “This is a religious donation of Āryaśrīmittra, an eminent follower of the Mahāyāna, a monk coming from Nepal. What here is the merit, may that be for the gain of the fruit of supreme wisdom by the whole multitude of beings, having placed first the teacher, preceptor, mother, and father. In the year 239 [Newar Era], on the 8th [tithi] in the bright fortnight of Āśvina, at the great monastery of Vikramaśīla.” Shin’ichirō Hori 2017. (International Institute for Buddhist Studies, Tokyo.) Personal communication. |

| 5 | Information from a record in the CMA’s curatorial file. For an art historical analysis of another illuminated Nepalese Prajñāpāramitā manuscript that discusses style as well as the original ritual contexts of northern Indian and Nepalese manuscripts, see (Melzer and Allinger 2010). |

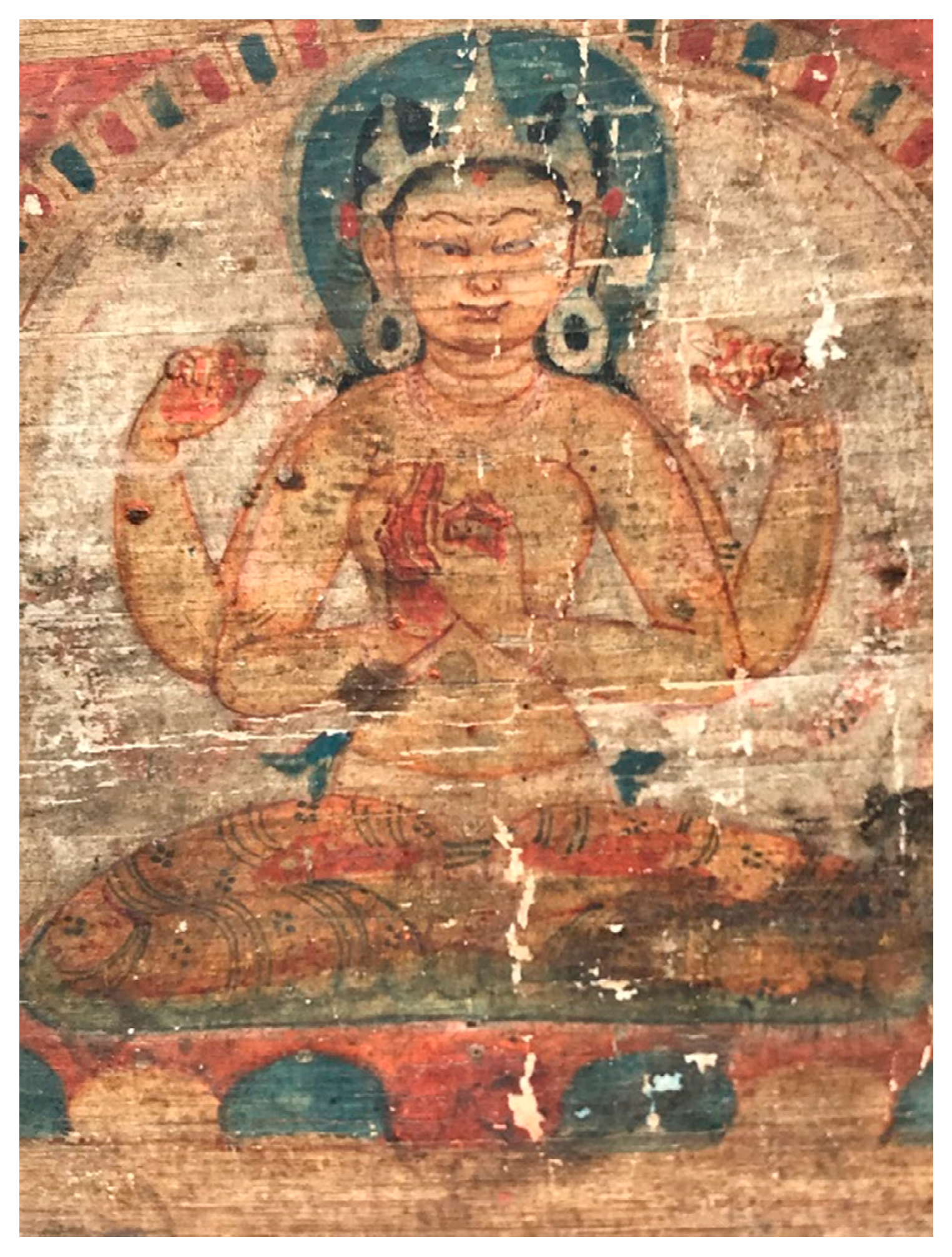

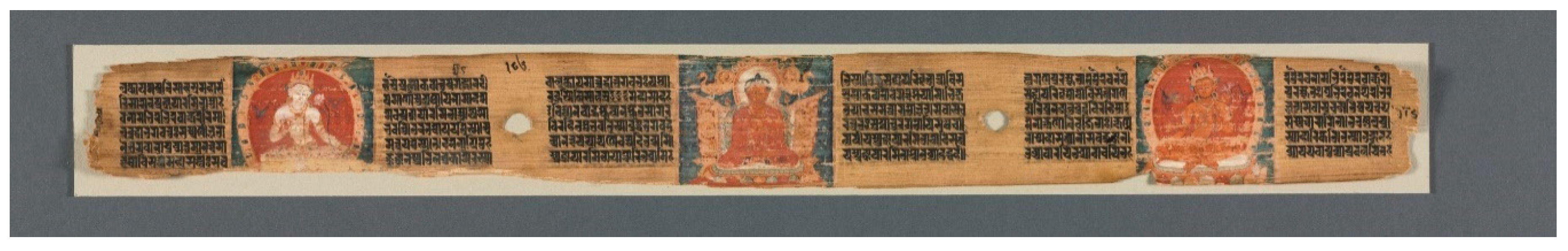

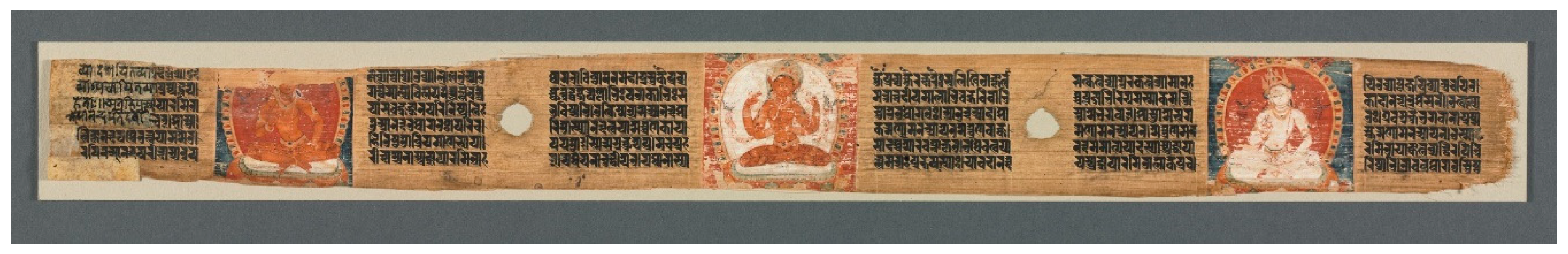

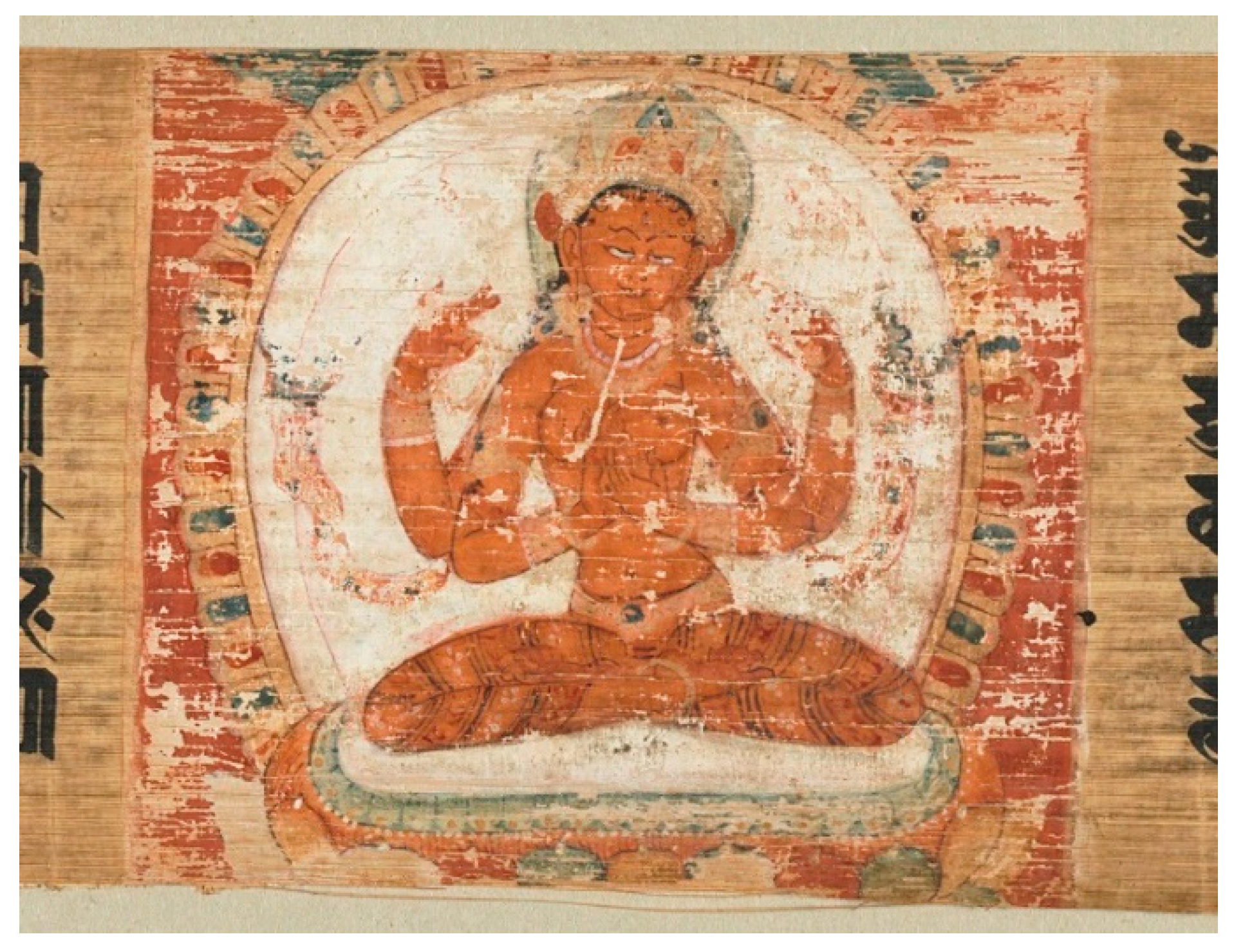

| 6 | Based on the measurements for the other leaves, folio 1v (Figure 1) appears to have been trimmed. In the manuscript’s current condition, the picture planes on folio 90r (Figure 5 and Figure 8) that house the central Prajñāpāramitā and two flanking white attendants are painted larger than those on folios 1v and 89v (Figure 1 and Figure 4). The paintings on 1v and 89v seem unfinished. The white wash of kaolinite used as an undercoat or a preparatory coat is still visible around the paintings on 1v and 89v. If the width of the kaolinite undercoat of the Prajñāpāramitā on folio 1v is measured, the width would be 6.2 cm and would have been commensurate with the red Prajñāpāramitā on folio 90r. Based on a comparison with the finished paintings at the end of the manuscript, a curtain above and a border under the lotus pedestal would have been intended. Although we cannot know why these paintings were left unfinished, this does suggest that the paintings were completed beginning with the covers and then the bottom or end of the pothi. Indeed, the gold borders and details such as the jewelry and the gold settings for the jewels in the haloes are filled in on folios 186v and 187r (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The gold detailing is possibly just a yellow pigment with traces of gold, as it does not have a noticeable metallic quality. Folio 90r has none of this gold color at all, and the border lines have only been drawn in. The jewelry has likewise not been filled in with gold. Folio 89v has even less of the painting finished (for example, it lacks the bolsters), and the preparatory ground layer remains visible. This is also the case for folio 1v. On folio 186v, there has also been some minor retouching to Avalokiteśvara and Mañjuśrī, probably when the manuscript was refurbished in the sixteenth(?) century or so. Sonya Rhie Mace 2020. (Cleveland Museum of Art.) Personal communication. |

| 7 | Kim has noted that the timeworn state of folio 1 (it is supported on the backside with Nepalese yellow paper) implies that the second folio may have also been damaged and therefore lost during its time in Nepal (Kim 2015, pp. 60 and 82, n. 16). |

| 8 | The original verses of the hymn in Sanskrit and in a German translation can be found in (Eimer 1988). |

| 9 | I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer who suggested that it should be possible to guess whether folio 2 was illustrated by looking at the amount of text missing between folios 1 and 3. Phyllis Granoff kindly identified the amount of missing text based on standard published texts of the hymn and the sūtra, and Sonya Rhie Mace made a rough count of akṣaras. Folio 1v with the three paintings has approximately 430 akṣaras; folio 3r with text only has 775 akṣaras, and folio 3v with text only has around 904 akṣaras. The number of akṣaras of missing text that would have fallen on folio 2, both recto and verso, would have been approximately 1140. Although these are rough estimates, it seems unlikely that folio 2 would have had text only on both the recto and verso. Sonya Rhie Mace 2020. (Cleveland Museum of Art.) Personal communication. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | For example, in chapter 12 (Conze 1975, p. 31) the text reads: “Just so also the Buddhas in the world-systems in the ten directions /Bring to mind this perfection of wisdom as their mother.” Chapter 12 and the rest of the Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra’s prose is filled with several examples mother imagery. |

| 12 | See, e.g., the Detroit manuscript (Acc. No. 27.586) and Kim (2008). In the article, Kim notes that this iconographical pairing is common, but the reason for it is unclear. She notes that in the hymn dedicated to Prajñāpāramitā, she is described as “boundless,” which may connect to Amitābha because his name means boundless light (p. 84). See also the chapter by Weissenborn (2012) for more examples of South Asian illuminated manuscripts containing figural images of both Amitābha and Prajñāpāramitā (e.g., number 6 [G.4713 from the Asiatic Society], number 17 [the Detroit manuscript], and others in her list). |

| 13 | In the Berlin/Kolkata image of Prajñāpāramitā, she holds her palm-leaf attribute, and interestingly, in the image of the Buddha, behind him and above his head is a five-leaved fan palm (Melzer and Allinger 2010, p. 7). |

| 14 | For example, the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra (A.15, dated to NS 191, or 1071 CE) now in the Asiatic Society in Kolkata, India, opens the first folio with an image of the Buddha preaching the Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra that is linked to an image of Prajñāpāramitā at the end of the first chapter. |

| 15 | For a similar example of Vairocana holding his extended left index finger in his right hand, see (Huntington and Bangdel 2003, pp. 108–9). |

| 16 | Another example of a manuscript that has Vajrayāna imagery as well as illuminations showing Prajñāpāramitā is a mid-twelfth-century pothi from Bihar in Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts (20.589); see (Weissenborn 2012). |

| 17 | The leftmost has a solar disk (cakra) on his lotus flower, while the rightmost has a crescent moon. The bodhisattva on the inner left has a blue lotus (utpala), while the one on the inner right has what appears to be flaming triple jewels on a white lotus. Their identity remains uncertain. It is interesting to note, however, that the leftmost bodhisattva is iconographically identical to the bodhisattva on the right of folio 90r (Figure 5). |

| 18 | E.g., for St. Bartholomew: Mittman and Sciacca (2017); and for a summary of the material-focused reception of the side wound of Christ: Areford (2012). Other essays in the Flaying in the Pre-Modern World volume (Tracy 2017) will likewise be relevant. For other western-focused “skin” and materiality studies, see: (Kay 2011; Holsinger 2009, 2010; Gertsman 2018). The discussion of carnal sin and the materiality of parchment comes up frequently in Biernoff (2012). For specifically art historical approaches to the subject, also see the works of, e.g., Sherry C.M. Lindquist, Martha Easton, and Michael Camille, among many others. |

| 19 | See also (Gertsman 2018). |

| 20 | One of the earliest surviving illustrated manuscripts from south Asia dates to ca. 983 CE (Kim 2013, p. 45). |

| 21 | According to Shin’ichirō Hori 2017. (International Institute for Buddhist Studies, Tokyo.) Personal communication. |

| 22 | This is accounted for specifically in Orissa. Tumeric (Curcuma longa) paste may have functioned not only aesthetically, but also as an insect repellent (Agrawal 1984, pp. 27, 29, and 276–77; Van Dyke 2009, p. 86). |

| 23 | In Kim (2013, p. 8 and n. 12), she notes the use of palm leaves as amulets or as “medicines of miraculous healing power” (p. 8). In Thailand, palm leaves (bai-larn) were made from a leaf from the Lopburi region known as the “golden leaf.” Thai pothi makers also gilded or colored the edges of the manuscripts with gold powder, vermillion, and lacquer as opposed to ironing the pages’ edges (Agrawal 1984, pp. 28 and 31). |

| 24 | Chapter 30 describes the shrine (kūṭāgāra) created by the bodhisattva Dharmodgata, which includes “a pointed tower, made of the seven precious substances, adorned with red sandalwood, and encircled by an ornament of pearls. Gems were placed into the four corners of the pointed tower, and performed the functions of lamps. Four incense jars made of silver were suspended on its four sides, and pure black aloe wood was burning in them, as a token of worship for the perfection of wisdom. And in the middle of that pointed tower a couch made of seven precious things was put up, and on it a box made of four large gems. Into that the perfection of wisdom was placed, written with melted vaidurya on golden tablets. And that pointed tower was adorned with brightly coloured garlands which hung down in strips […] They saw thousands of Gods, with Śakra, Chief of Gods, scattering over that pointed tower heavenly Mandarva flowers, heavenly sandalwood powder, heavenly gold dust, and heavenly silver dust, and they heard the music of heavenly instruments” (emphasis added). The italicized in the original Sanskrit is: yatra prajñāpāramitā prakṣiptā suvarṇapaṭṭeṣu likhitā vilīnena vaidūryeṇa. (Conze 1975, pp. 288–89). Melzer and Allinger also discuss the luxury of the Prajñāpāramitā (Melzer and Allinger 2010, pp. 15–16). |

| 25 | For several regional differences in palm-leaf manuscript production, see (Agrawal 1984, pp. 27–31; Van Dyke 2009, p. 86). Kim (2013, pp. 253–54) also discusses the pothi making process briefly. |

| 26 | For more on this manuscript, see (Kim 2015, p. 59). |

| 27 | This is from chapter 32 of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā-sūtra and is reproduced in Kim (2013, pp. 1, 37). |

| 28 | (Conze 1975, chp. 11 (p. 49) and chp. 28 (p. 61)). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Mara, R. “On Golden Tablets”: The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript as a Self-Referential Icon. Religions 2020, 11, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060274

O’Mara R. “On Golden Tablets”: The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript as a Self-Referential Icon. Religions. 2020; 11(6):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060274

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Mara, Reed. 2020. "“On Golden Tablets”: The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript as a Self-Referential Icon" Religions 11, no. 6: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060274

APA StyleO’Mara, R. (2020). “On Golden Tablets”: The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript as a Self-Referential Icon. Religions, 11(6), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060274