Content Analysis of Spiritual Life in Contemporary USA, India, and China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Universal Spirituality

2. Spiritual Life Across Three Countries

2.1. USA: Polarization of Religion and Spirituality

2.2. India: Secularism and Spirituality

2.3. China: Religious Revival and Syncretism

3. Aims of Study

4. Method

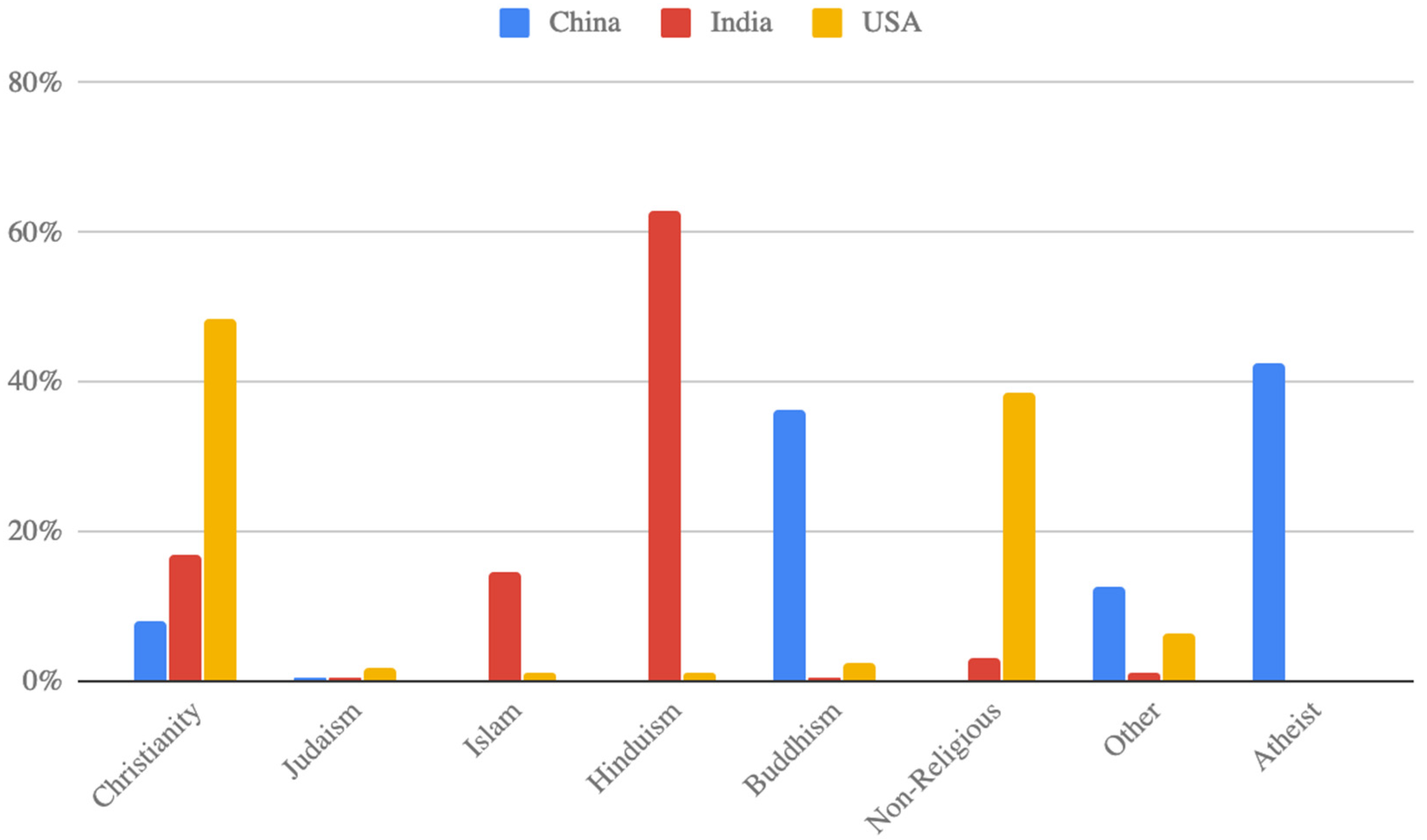

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measures

4.3. Procedure

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Commonalities in Spiritual Life

6.2. Differences in Spiritual Life

6.3. Cultural and Historical Factors

6.4. Theory of Religion and Culture

7. Limitations

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Exemplar Excerpts of the Coding Frame

Appendix A.1. Religion

Religious Tradition

Appendix A.2. Religious Conversion

Appendix A.2.1. Convert Back into a Religion

Appendix A.2.2. Convert into a Religion

Appendix A.2.3. Convert Out of a Religion

Appendix A.2.4. Religious Professionals

Appendix A.3. Religious Figure (Theophany)

Appendix A.4. Religious Force (Hierophany)

Appendix A.5. Contemplative Practice

Appendix A.6. Ancestors

Appendix A.7. Natural World

Appendix A.8. Metaphysical Phenomena

Appendix A.8.1. Extrasensory Experience (ESP)

Appendix A.8.2. Psychokinesis

Appendix A.8.3. Survival Hypothesis

Appendix A.8.4. Faith/Energy Healing

References

- Ager, Alastair, and Joey Ager. 2011. Faith and the discourse of secular humanitarianism. Journal of Refugee Studie 24: 456–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijmer, Göran. 1968. A structural approach to Chinese ancestor worship. Bijdragen tot de Taal- Land-en Volkenkunde 124: 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. 1990. Durkheimian Sociology: Cultural Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Angelskår, Trine. 2013. China’s Buddhist Diplomacy. Available online: http://noref.no/Regions/Asia/Publications/China-s-Buddhist-diplomacy/(language)/eng-US (accessed on 7 June 2020).

- Aurobindo, Sri. 1919. Indian Spirituality and Life–1. Available online: http://intyoga.online.fr/isl01.htm (accessed on 7 June 2020).

- Baird, Robert D. 2004. Syncretism and the History of Religions. Edited by Syncretism A. Reader. London: Leopold &Jensen, Equinox, pp. 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Hugh. 1965. Burial, geomancy and ancestor worship. In Aspects of Social Organization in the New Territories. Edited by Marjorie Topley. Hong Kong: Royal Asiatic Society, pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Beckford, James A., and James T. Richardson. 2007. Religion and regulation. In The SAGE Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by James A. Beckford and N. J. Demerath III. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bellenoit, Hayden J. A. 2007. Missionary education, religion and knowledge in India, c. 1880–1915. Modern Asian Studies 41: 369–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, Vern L., Merril Silverstein, Norella M. Putney, and Susan C. Harris. 2015. Does religiousness increase with age? Age changes and generational differences over 35 years. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawuk, Dharm P. S. 2003. Culture’s influence on creativity: The case of Indian spirituality. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 27: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, Julius Seelye. 1926. Religion in the Philosophy of William James. Boston: Marshall Jones. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. 1986. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall-Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brook, Timothy. 1989. Funerary ritual and the building of lineages in late imperial china. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 49: 465–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Shixiong. 2012. Socioeconomic value of religion and the impacts of ideological change in China. Economic Modelling 29: 2621–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2011. Grounded theory methods in social justice research. The Sage handbook of qualitative research 4: 359–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Lyren, Julia D. Emblen, Lynn Van Hofwegen, Rick Sawatzky, and Heather Meyerhoff. 2004. An integrative review of the concept of spirituality in the health sciences. Western Journal of Nursing Research 26: 405–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, Ajit K., and Girishwar Misra. 2010. The core and context of Indian psychology. Psychology & Developing Societies 22: 121–55. [Google Scholar]

- Davey, Gareth, Chuan De Lian, and Louise Higgins. 2007. The university entrance examination system in China. Journal of Further and Higher Education 31: 385–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Julian M. 1976. The physiology of meditation and mystical states of consciousness. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 19: 345–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager Meezenbroek, Eltica, Bert Garssen, Machteld van den Berg, Dirk Van Dierendonck, Adriaan Visser, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2012. Measuring spirituality as a universal human experience: A review of spirituality questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 336–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delaney, Colleen. 2005. The spirituality scale development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension. Journal of Holistic Nursing 23: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirks, Nicholas B. 1997. The policing of tradition: Colonialism and anthropology in southern India. Comparative Studies in Society and History 39: 182–212. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, Penny. 2012. A cultural sociology of religion: New directions. Annual Review of Sociology 38: 247–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Adrian, Nannan Pang, Vanessa Shiu, and Cecilia Chan. 2010. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: A meta-study of qualitative research. Palliative Medicine 24: 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, Kusum Lata, and Mahesh Sharma. 2014. Measuring Spiritual Health: Spiritual Health Assessment Scale (SHAS). International Journal of Innovative Research and Development 3: 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1993. Religion as a cultural system. In The Interpretations of Cultures: Selected Essays. St Waukegan: Fontana Press, pp. 87–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ger, Güliz, and Russell W. Belk. 1995. Cross-cultural differences in materialism. Journal of Economic Psychology 17: 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerrish, Brian Albert. 2001. A Prince of the Church: Schleiermacher and the Beginnings of Modern Theology. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent, and David A. Palmer. 2011. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2007. Religious persecution in cross-national context: Clashing civilizations or regulated religious economies? American Sociological Review 72: 633–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, David D. 1997. Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, Fred J., and Alan Green. 2004. Asian shades of spirituality: Implications for multicultural school counseling. Professional School Counseling 7: 326–33. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, Stevan. 1977. Modes of belief in Chinese folk religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 16: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, Stevan. 1979. The concept of soul in Chinese folk religion. The Journal of Asian Studies 38: 519–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Peter C., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2008. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. American Psychologist 58: 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hornell, James. 1944. The ancient village gods of South India. Antiquity 18: 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtman, Dick, Stef Aupers, and Paul Heelas. 2009. Christian religiosity and new age spirituality: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Jiann. 1986. China’s nationalities policy: Its development and problems. Anthropos 81: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Harvey J., and Caroline A. Watt. 2007. An Introduction to Parapsychology, 5th ed. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1977. Conclusions to the varieties of religious experience. In The Writings of William James. Edited by John J. McDermott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 758–82. First published 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Li-Jun, Kaiping Peng, and Richard E. Nisbett. 2000. Culture, control, and perception of relationships in the environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78: 943–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Zhe. 2006. Non-institutional religious re-composition among the Chinese youth. Social Compass 53: 535–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, Heather S. L., James E. Pustejovsky, Crystal L. Park, Suzanne C. Danhauer, Allen C. Sherman, George Fitchett, and Thomas V. Merluzzi. 2015. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer 121: 3760–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Dan R., and Lauren A. Borden. 2012. Participants at your fingertips: Using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to increase student-faculty collaborative research. Society for the Teaching of Psychology 39: 245–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandari, Laxman Singh, Vinod Kumar Bisht, Meenakshi Bhardwaj, and Ashok Kumar Thakur. 2014. Conservation and management of sacred groves, myths and beliefs of tribal communities: A Case study from north-India. Environmental Systems Research 3: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendler, Kenneth S., Charles O. Gardner, and Carol A. Prescott. 1997. Religions, psychopathology, and substance use and abuse; a multi-measure, genetic-epidemiologic study. American Journal of Psychiatry 154: 322–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kendler, Kenneth S., Charles O. Gardner, and Carol A. Prescott. 1999. Clarifying the relationship between religiosity and psychiatric illness: The impact of covariates and the specificity of buffering effects. Twin Research and Human Genetics 2: 137–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, Eliza F. 2013. Sacred Groves and Local Gods: Religion and Environmentalism in South India. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Martin. 2007. Text and Ritual in Early China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeller, Jean L., and Kevin D. Jordan. 2017. Spirituality and meditative practice: Research opportunities and challenges. Psychological Studies 63: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Hongyi Harry. 2005. The religious revival in China. The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies 18: 40–64. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Jeff. 2011. Energy healers: Who they are and what they do. The Journal of Science and Healing 7: 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wai-yee. 1999. Dreams of interpretation in early Chinese historical and philosophical writings. In Dream Cultures: Explorations in the Comparative History of Dreaming. Edited by David Dean Shulman and Guy G. Stroumsa. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Liping. 2012. Multiple variations: Perspectives on the religious psychology of Buddhist and Christian converts in the People’s Republic of China. Pastoral Psychology 61: 865–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizhu, Fan. 2003. Popular religion in contemporary China. Social Compass 50: 449–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Jennifer Ung. 2014. Narrating identity: The employment of mythological and literary narratives in identity formation among the Hijras of India. Religion and Gender 4: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luhrmann, Tanya Marie. 2014. To Dream in Different Cultures. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/14/opinion/luhrmann-to-dream-in-different-cultures.html (accessed on 22 April 2019).

- Madsen, Richard. 2011. Religious renaissance in China today. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 40: 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malhotra, Neil. 2008. Completion time and response order effects in web surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 914–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, Clayton H., Elsa Lau, and Lisa Miller. 2016. Phenotypic dimensions of spirituality: Implications for mental health in China, India, and the United States. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKinnon, Andrew. 2014. Elementary forms of the metaphorical life: Tropes at work in Durkheim’s theory of the religious. Journal of Classical Sociology 14: 203–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, Jon, and Gregory Stanczak. 2009. Redeeming, ruling, and reaping: British missionary societies, the East India company, and the India-to-China opium trade. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 332–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Lisa, Iris M. Balodis, Clayton H. McClintock, Jiansong Xu, Cheryl M. Lacadie, Rajita Sinha, and Marc N. Potenza. 2019. Neural correlates of personalized spiritual experiences. Cerebral Cortex 29: 2331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Lisa, Ravi Bansal, Priya Wickramaratne, Xuejun Hao, Craig E. Tenke, Myrna M. Weissman, and Bradley S. Peterson. 2014. Neuroanatomical correlates of religiosity and spirituality: A study in adults at high and low familial risk for depression. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moberg, David O. 2002. Assessing and measuring spirituality: Confronting dilemmas of universal and particular evaluative criteria. Journal of Adult Development 9: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, Brona, and Fiona Timmins. 2007. Spirituality as a universal concept: Student experience of learning about spirituality through the medium of art. Nurse Education in Practice 7: 275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, Rene J. 2008. Neurotheology: Are we hardwired for god? Psychiatric Times 25: 24. [Google Scholar]

- Newberg, Andrew B., and Stephanie K. Newberg. 2008. Hardwired for god: A neurotheological model for developmental spirituality. In The Search Institute Series on Developmentally Attentive Community and Society (Volume 5). Edited by Kathleen Kovner Kline. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Newberg, Andrew, Michael Pourdehnad, Abass Alavi, and Eugene G. d’Aquili. 2003. Cerebral blood flow during meditative prayer: Preliminary findings and methodological issues. Perceptual and Motor Skills 97: 625–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, Suzanne. 2009. The development of modern yoga: A survey of the field. Religion Compass 3: 986–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickolas, Markos, Alice Hayes, Patricia Hughes, Dean Hammer, Ann Clarke, Kenneth Pargament, and Carrie Doehring. 2009. Perceiving Sacredness in life: Correlates and predictors. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 31: 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr, Richard R. 1964. Schleiermacher on Christ and Religion: A New Introduction. New York: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, Richard E., and Yuri Miyamoto. 2005. The influence of culture: Holistic versus analytic perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, Roberto K. 1985. The Interpretation of Dreams in Ancient China. Bochum: Seiten. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, Rudolf. 1958. The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational. Translated by John W. Harvey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Paden, William E. 1991. Before “the sacred” become theological: Rereading the Durkheimian legacy. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 3: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 1999. Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality 67: 985–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L., and Mark M. Leach. 2002. Cross-cultural generalizability of the spiritual transcendence scale in India: Spirituality as a universal aspect of human experience. American Behavioral Scientist 45: 1888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoshen, Jeffrey S., Lu Li, and Junfeng Zhang. 2011. Materialism and conspicuous consumption in China: A cross-cultural examination. International Journal of Consumer Studies 35: 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, Pitman B. 2003. Belief in control: Regulation of religion in China. The China Quarterly 174: 317–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhavananda, Swami. 2019. The Spiritual Heritage of India (Vol. 10). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Laurence W. 2002. Shrines and neighborhood in early nineteenth-century Pune, India. Journal of Historical Geography 28: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, Lewis R. 1999. Theories of conversion: Understanding and interpreting religious change. Social Compass 46: 259–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphals, Lisa. 2014. Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reinstein, Ellen S. 2004. Turn the other cheek, or demand an eye for an eye? Religious persecution in China and an effective western response. Connecticut Journal of International Law 20: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Larry T., and Nancy J. Herman. 1994. Symbolic Interaction: An Introduction to Social Psychology. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rican, Pavel, and Pavlina Janosova. 2010. Spirituality as a basic aspect of personality: A cross-cultural verification of Piedmont’s model. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rol, Cécile. 2012. Animism and totemism: Durkheim versus Wundt. L’annee Sociologique 62: 351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roof, Wade Clark, and William McKinney. 1987. American Mainline Religion: Its Changing Shape and Future. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roof, Wade Clark. 2001. Spiritual Marketplace: Baby Boomers and the Remaking of American Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Heidi, and Yimin Wang. 2010. The college entrance examination in China: An overview of its social-cultural foundations, existing problems, and consequences. Chinese Education and Society 43: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottman, Joshua, Liqi Zhu, Wen Wang, Rebecca Seston Schillaci, Kelly J. Clark, and Deborah Kelemen. 2017. Cultural influences on the teleological stance: Evidence from China. Religion, Brain, & Behavior 7: 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Himanshu. 2006. Western secularism and colonial legacy in India. Economic and Political Weekly 41: 158–65. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2010. Religiousness as a cultural adaptation of basic traits: A five-factor model perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 108–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sawatzky, Rick, Pamela A. Ratner, and Lyren Chiu. 2005. A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research 72: 153–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, Linda J., Shannon K. Gilmartin, and Alyssa N. Bryant. 2003. Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Research in Higher Education 44: 409–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Robert A. 2012. Clifford Geertz’s interpretive approach to religion. Religion Compass 6: 511–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, Marshall H., Donald Thomas Campbell, and Melville Jean Herskovits. 1968. The influence of culture on visual perception. In Social Perception. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat, Darren E., and John Wilson. 1995. Preferences, constrains, and choices in religious markets: An examination of religious switching and apostasy. Social Forces 73: 993–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaggs, Brenda G., and Cecilia R. Barron. 2006. Searching for meaning in negative events: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 53: 559–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian, and David Sikkink. 2003. Social predictors of retention in and switching from the religious faith of family of origin: Another look using religious tradition self-identification. Review of Religious Research 45: 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, Allison, Linda H. Aiken, Koen Van den Heede, Walter Sermeus, Luk Bruyneel, Rikard Lindqvist, and Lisette Schoonhoven. 2013. A systematic survey instrument translation process for multi-country, comparative health workforce studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50: 264–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutton, Donald S. 2007. Death rites and Chinese culture: Standardization and variation in Ming and Qing times. Modern China 33: 125–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teiser, Stephen F. 1986. Ghosts and ancestors in medieval Chinese religion: The Yü-lan-p’en festival as mortuary ritual. History of Religions 26: 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaibourne, Michael A., and Peter S. Delin. 1999. Transliminality: Its relation to dream life, religiosity, and mystical experience. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, Romila. 1989. Imagined religious communities? Ancient history and the modern search for a Hindu identity. Modern Asian Studies 23: 209–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Laurence G. 1988. Dream, divination and Chinese popular religion. Journal of Chinese Religions 16: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, Lynn G., and Jeanne A. Teresi. 2002. The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, Mojtaba, Hannele Turunen, and Terese Bondas. 2013. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences 15: 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veer, Peter. 2009. Spirituality in modern society. Social Research: An International Quarterly 76: 1097–120. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Roger. 1989. Can western philosophers understand Asian philosophies? The challenge and opportunity of states-of-consciousness research. CrossCurrents 39: 281–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Barbara E. 1979. Not merely players: Drama, art and ritual in traditional China. Man, New Series 14: 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, Peter M. 1956. Emile Durkheim’s theory of knowledge. The Sociological Review 4: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Lan, and Hoi K. Suen. 2005. Historical and contemporary exam-driven education ever in China. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy 2: 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., D. Du, and Shuangju Zhen. 2011. Belief systems and positive youth development among Chinese and American youth. Thriving and Spirituality Among Youth: Research Perspectives and Future Possibilities, 309–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Allie B. Scott. 1999. The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality 67: 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | China | India | USA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 29 years, Range 18–75 year | ||

| Gender | % | % | % |

| Female | 40.5 | 62.3 | 45.6 |

| Male | 59.3 | 37.7 | 54.4 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 25.2 | 51.3 | 38.6 |

| Widowed/divorced | 1.3 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Single never married | 73.3 | 46.1 | 50.2 |

| Children | |||

| Yes | 17 | 41.9 | 42.3 |

| No | 82.7 | 57.6 | 57.7 |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Straight | 94.4 | 80.6 | 89.4 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.5 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Bisexual | 1.8 | 11.5 | 5.5 |

| Education Level | |||

| Some high school/High school degree | 6.6 | 2.6 | 14 |

| Some college/Associate degree | 44.8 | 9.4 | 39.3 |

| Undergraduate degree | 42 | 46.6 | 33.8 |

| Graduate degree | 6.4 | 40.3 | 12.8 |

| Estimated Personal Income | |||

| Above 75th percentile | 6.9 | 24.6 | 6 |

| Between 50–75th percentile | 14.2 | 24.1 | 15.3 |

| Between 25–50th percentile | 40.2 | 22.5 | 26.0 |

| Below 25th percentile | 38.4 | 27.7 | 52.1 |

| Environment prior to age 18 | |||

| Urban | 20.6 | 44.5 | 24.1 |

| Suburban | 13 | 22.5 | 50.1 |

| Rural | 41 | 23.0 | 21.3 |

| Mixed | 25.4 | 9.4 | 4.5 |

| Theme | Subthemes | USA | India | China |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religion | 83 | 86 | 58 | |

| Traditional Religious Practices | 77 | 61 | 38 | |

| Religious Conversion | 23 | 7 | 2 | |

| Religious Professionals | 16 | 20 | 7 | |

| Theophany (religious figure such as Jesus) | 48 | 70 | 36 | |

| Hierophany (religious force such as holy spirit) | 6 | 9 | 5 | |

| Contemplative Practice | 60 | 72 | 51 | |

| Meditation | 11 | 15 | 4 | |

| Mind–body Practices | 4 | 9 | 2 | |

| Prayer | 52 | 66 | 48 | |

| Rituals/Ceremonies | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| Natural World | 29 | 5 | 19 | |

| Nature | 25 | 3 | 12 | |

| Animals | 8 | 3 | 10 | |

| Ancestors | 32 | 18 | 33 | |

| Ancestor Mentioned | 22 | 12 | 19 | |

| Ancestral Worship | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Ancestor Dream | 15 | 8 | 17 | |

| Metaphysical Phenomena | 75 | 64 | 69 | |

| Extrasensory Perception | 51 | 39 | 56 | |

| Telepathy | 5 | 2 | 6 | |

| Clairvoyance | 13 | 5 | 6 | |

| Precognition | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Realistic Dreams | 25 | 18 | 34 | |

| Intuitive Impressions | 27 | 21 | 32 | |

| Psychokinesis | 7 | 7 | 4 | |

| Survival Hypothesis | 30 | 21 | 22 | |

| Near Death Experience | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Out of Body Experience | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| Apparitional Experience | 27 | 16 | 20 | |

| Faith/Energy Healing | 18 | 29 | 21 | |

| Recovery/Remission of Illness | 17 | 23 | 18 | |

| Spiritual Practitioners | 1 | 7 | 6 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lau, E.; McClintock, C.; Graziosi, M.; Nakkana, A.; Garcia, A.; Miller, L. Content Analysis of Spiritual Life in Contemporary USA, India, and China. Religions 2020, 11, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060286

Lau E, McClintock C, Graziosi M, Nakkana A, Garcia A, Miller L. Content Analysis of Spiritual Life in Contemporary USA, India, and China. Religions. 2020; 11(6):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060286

Chicago/Turabian StyleLau, Elsa, Clayton McClintock, Marianna Graziosi, Ashritha Nakkana, Albert Garcia, and Lisa Miller. 2020. "Content Analysis of Spiritual Life in Contemporary USA, India, and China" Religions 11, no. 6: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060286

APA StyleLau, E., McClintock, C., Graziosi, M., Nakkana, A., Garcia, A., & Miller, L. (2020). Content Analysis of Spiritual Life in Contemporary USA, India, and China. Religions, 11(6), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060286