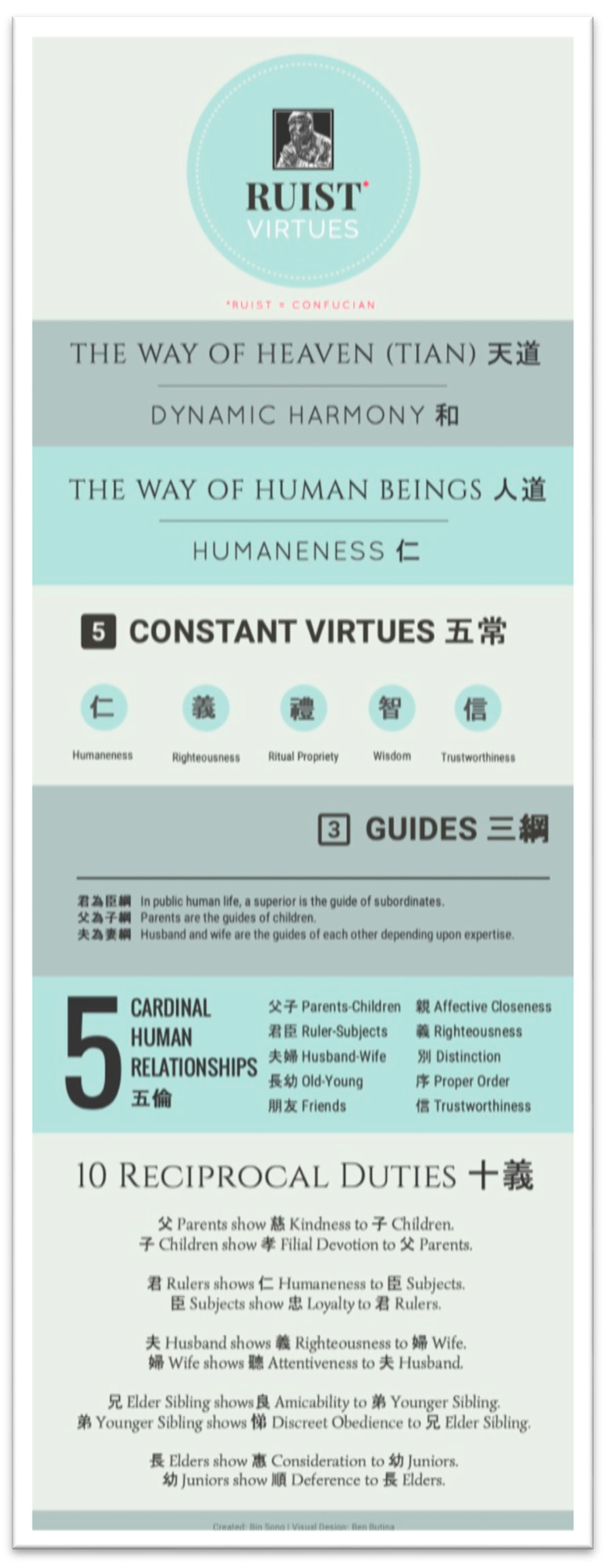

Contemporary Business Practices of the Ru (Confucian) Ethic of “Three Guides and Five Constant Virtues (三綱五常)” in Asia and Beyond

Abstract

:1. History and Philosophy of the Ethic of Three Guides and Five Constant Virtues

1.1. Historical Context

“Zi Zhang asked, ‘Can we know what it will be like ten generations from now?’ The Master responded, ‘The Yin followed the rituals of the Xia, altering them only in ways that we know. The Zhou followed the rituals of the Yin, altering them only in ways that we know. If some dynasty succeeds the Zhou, we can know what it will be like even a hundred generations from now.’”5

“…such great criminals are greatly abhorred, and how much more (detestable) are the unfilial (不孝) and unbrotherly (不友)!-as the son who does not reverently discharge his duty to his father, but greatly wounds his father’s heart, and the father who can no longer love his son, but hates him; as the younger brother who does not think of the manifest will of Tian (heaven or cosmos) and refuses to respect his elder brother, and the elder brother who does not think of the suffering of his junior, and is very unfriendly to his younger brother. If we who are charged with government do not treat parties who proceed to such wickedness as offenders, the constant nature given by Tian (天惟與我民彝) to our people will be thrown into great disorder and destroyed.”

1.2. Philosophy

2. Contemporary Debate on the Ethic of TGFV

2.1. Three Phases of the Debate

“The doctrine of Three Guides in the Ru tradition is the ultimate origin of all ethical and political discourses. Since the ruler as the guide of the subjects, the people have become an accessory of the ruler and lost their independent and autonomous personality. Since the father as the guide of the son, sons have become an accessory of the father and lost their independent and autonomous personality. Since the husband as the guide of the wife, wives have become an accessory of the husband and lost their independent and autonomous personality. Among all the men and women under heaven who are subjects, children or wives, there is no single one of them who has been able to be independent and autonomous; and this is what the doctrine of Three Guides has led to. Other ethical terms which derive from the doctrine and are embraced as golden rules, including Loyalty, Filiality and Chastity, all belong to the morality of slaves who subordinate themselves to others, and hence, none of them belongs to the morality of masters who extend themselves to others.”

“The reading and learning of scholar-officials (士) aims to emancipate their heart and will from the shackles of vulgar opinions so that truth can be discovered and spread. In this sense, if one’s thought cannot be free, one would rather like to die. (思想不自由,毋寧死耳).”

“The definition of our Chinese culture is all summarized in the ethic of Three Guides and Six Orders which was explained in the text of ‘A Comprehensive Exposition in White Tiger Hall.’ The ethic intends to address the highest being of abstract ideals, just as what the Greek philosopher Plato referred to by ‘Eidos.’ If we talk of the guide between the ruler and subjects, even if the ruler is (as bad as) Li Yu, (loyal ministers) should hope him to become as good as Liu Xiu. If we talk of the order between friends, even if one’s friend is (as bad as) Li Ji, (a trustful friend) should wish him or her to become as good as Bao Shu. From here we know that both the Way one sacrifices for and the Goodness that one tries to accomplish (like Wang Guowei did) have a universal nature shared by all abstract ideals, and these ideals cannot be limited by any particular person or thing.”

“The original meaning of Three Guides is never about unconditional obedience. It refers to a spirit of thinking from a holistic perspective, and thus, making one’s ‘small self’ act in accordance with a ‘big self.’ The ethic of Three Guides is an antidote devised by Kongzi to cure the division and chaos caused by wars rampant in his time; the spirit of Three Guides is still ubiquitously applicable in people’s ordinary life today, and is also one of the conditions that China can build a healthy and complete democracy in the future.”

“From the Confucian philosophical perspective, however, the relationship between the employer-organization and the employee ought not to be treated on an equal footing. The employee is expected to show ‘filial love’ to the employer, but may not necessarily demand the same love to be shown by the employers towards them.”

2.2. Method

The Ru tradition, as historically represented by the ethic of Three Guides and Five Constant Virtues, is ethically committed to realizing the reciprocal autonomy of individual in varying human relationships for the overall purpose of creating evolving forms of dynamic harmony, and whenever and wherever the Ru tradition migrates, this ethical commitment can be held onto by Ru practitioners as a constant moral principle despite contexts and changes.

3. Shibusawa Eiichi’s Ru Business Practices

3.1. Reciprocal Autonomy for Shibusawa Eiichi

3.1.1. Individuals

“There is one saying of Kongzi’s from the Analects 15:36, ‘For the sake of (the cardinal virtue of) humaneness, you do not need to yield to your teacher.’ Evidently, Kongzi’s saying implies the idea of ‘right,’ since it urges that as long as an individual has his or her own right reason, he or she should insist upon it. A teacher is respectable, but for the sake of practicing the virtue of humaneness, one does not even need to yield to one’s teacher.”

3.1.2. Labor Relationship

“…the Kyochokai’s approach to worker education was clearly Confucian by assuming that education was primarily a ‘moral enterprise’ and that the ‘most effective method for producing the morally superior man was through moral example of superiors conveyed through close personal ties.’ In Kyochokai schools, this moral example was carried out by teachers and students (workers) mixing on an egalitarian basis. Kyochokai educational programs thus strove to carry out Shibusawa’s (and Home Ministry’s) vision of worker ‘self-cultivation,’ leading to a harmonious modern industrial society.”

3.1.3. Business and State

4. Peter Drucker Champions the Ethic of TGFV

“The ethics of interdependence, as Confucian philosophers first codified it shortly after their Master’s death in 479 BC, considers illegitimate and unethical the injection of power into human relationships. It asserts that interdependence demands equality of obligation. Children owe obedience and respect to their parents. Parents, in turn, owe affection, sustenance and, yes, respect, to their children. … For every minister who risks his job, if not his life, by fearlessly correcting an Emperor guilty of violating harmony, there is an emperor laying down his life rather than throw a loyal minister to the political wolves.”

“Can an ethics of interdependence be anything more than ethics for individuals? The Confucians say no–a main reason why Mao (Zedong) outlawed them. …For ethics deals with the right actions of individuals. And then it surely makes no difference whether the setting is a community hospital, with the actors a nursing supervisor and the consumer a patient, or whether the setting is National Universal General Corporation, the actors a quality control manager, and the consumer the buyer of a bicycle.”

“A society of organizations is a society of interdependence. The specific relationship which the Confucian philosopher postulated as universal and basic may not be adequate, or even appropriate, to modern society and to the ethical problems within the modern organization and between the modern organization and its clients, customers, and constituents. But the fundamental concepts surely are. Indeed, if there ever is a viable ethics of organization, it will almost certainly have to adopt the key concepts which have made Confucian ethics both durable and effective.”

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Confucianism” is a misnomer devised by Protestant Christian missionaries around the 19th century, viz., the time of Western colonialism, to refer to the Ru (儒, civilized human) tradition with a primary purpose of religious comparison and conversion, just as Islam was once called “Muhammadanism” in a similar historical context. Following the reflective scholarly trend upon the nomenclature, “Confucianism” will be written as “Ruism” or the “Ru tradition,” and “Confucian” or “Confucianist” will be written as “Ru” or “Ruist” in this article. However, to respect the use of “Confucianism” and its related terms by discussed scholars, I will still keep their original use of “Confucianism” in quotations. For readers who are interested in exploring the naming history of “Confucianism” in the West, a detailed explanation of the history using the disciplinary approach of religious studies can be found at (Swain 2017, pp. 3–22), and (Sun 2013, pp. 45–76). Meanwhile, from the perspective of philosophical historiography, please refer to (Ambrogio 2020, p. 110). My own elaboration about the meaning of Ru and the misnomer of Ruism can be checked at (Song 2016). |

| 2 | A fuller account of the significance of these categories for contemporary Ruism can be found at (Bendik-Keymer 2021). About the religious self-identity of a Ru in a global context, please see (Sun 2020). |

| 3 | See my further analysis on this issue in (Song 2019). |

| 4 | A further overview of the scholarship on the post-Confucian hypothesis can be found at (Song 2018b, pp. 73–77). |

| 5 | Translations of original Chinese texts and (Shibusawa 1996) in this article are my own. Some of my own translations are adapted from other translators’, and in these cases, I include these translators’ works in the reference (Kongzi (Confucius) 2003). |

| 6 | The meaning of Tian undergoes change in Pre-Qin classical Ruism. My conception of it articulated here is based upon the Xici (Appended Texts) of the Classic of Change, as well as other Ru classics and commentaries which connects to Xici’s cosmological thought. For more details, please see (Song 2018a, chp. 5). |

| 7 | The following summary aims to highlight the intensity of the debate on the nature of the Ru ethic of TGFV, particularly on its contested idea of reciprocal autonomy, in the concerned period of time. It claims no exhaustion of the significant cases of the debate, and does not intend to address contemporary debates on Ru ethics in general. I thank one anonymous reviewer for asking me to make this clarification. |

| 8 | I analyzed the cause of the radical anti-Ru rhetoric in early modern China and how it evolves in (Song 2021). |

| 9 | A generic analysis of cultural conservatism interacting with other trends of thought in modern China can be found at (Fung 2010, pp. 145–58 and pp. 200–55). |

| 10 | The Six Orders refer to six minor reciprocal relationships after the main ones specified by the Three Guides, and they are the relationship among one’s father and uncles (from the father’s family), elder and younger siblings, the one among people in the same extensive family who share the same surname, the one among male relatives in one’s mother’s and wife’s extensive families, teacher and student, and the one between friends. (Ban 1778, vol. 7, p. 29) |

| 11 | See the example of the view of Li Cunshan’s in (Fang 2014, pp. 128–60). |

| 12 | The prescriptive nature of the stated hypothesis also makes my method of verification different from the one of quantitative research which aims to select random empirical evidence to test a descriptive hypothesis. What I intend to achieve in the following discussion is to present real empirical examples of the hypothesis so as to illustrate that my favored interpretation of the ethic of TGFV is practicable, and the practices can also generate positive societal effects. I thank an anonymous reviewer for asking me to make this clarification. |

| 13 | See (Tanaka 2017), and (Song 2018b, pp. 80–81). |

| 14 | The translation is my own. |

| 15 | On this point, see (Ornatowski 1996) and (Kikkawa 2017). |

| 16 | There are multiple occasions in Drucker’s writings where the case of Shibusawa Eiichi was studied. See the summary in (Sagers 2018, p. 16). |

| 17 | A similar view is expressed by Fang Chaohui in (Fang 2014, pp. 29–30). |

| 18 | On Drucker’s management thought of knowledge workers, see (Hunter and Scherer 2010) and (Turriago-Hoyos et al. 2016). |

| 19 | See the proof of the origin furnished by (Teng 1943). |

References

- Ambrogio, Selusi. 2020. Chinese and Indian Ways of Thinking in Early Modern European Philosophy: The Reception and the Exclusion. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, Gu. 1778. 白虎通義 Bai Hu Tong Yi. 摛藻堂四庫全書薈要本 The Version of Chi Zao Tang Si Ku Quan Shu Hui Yao. Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=en&res=4812 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Bendik-Keymer, Jeremy. 2021. Practical Enlightenment: Bin Song (Part II). Blog of the APA. March 19. Available online: https://blog.apaonline.org/2021/03/19/practical-enlightenment/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Chan, Gary Kok Yew. 2008. The Relevance and Value of Confucianism in Contemporary Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 77: 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Duxiu. 1993. 陈独秀著作选 Chen Du Xiu Zhu Zuo Xuan. Edited by Ren Jianshu, Zhang Tongmo and Wu Xinzhong. Shanghai: Shang Hai Ren Min Chu Ban She, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yinke. 1980. 清華大學王觀堂先生紀念碑銘 Qing Hua Da Xue Wang Guan Tang Xian Sheng Ji Nian Bei Ming. In 陳寅恪文集三:金銘館叢稿二編 Chen Yin Que Wen Ji (3): Jin Ming Guan Cong Gao Er Bian. Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She, p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yinke. 2000. 王觀堂先生輓詞並序 Wang Guan Tang Xian Sheng Wan Ci Bing Xu. In 陳寅恪集: 詩集 Chen Yin Ke Ji: Shi Ji. Beijing: San Lian Shu Dian, pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Zhongshu. 1792. 春秋繁露 Chun Qiu Fan Lu. 欽定四庫全書本 The Version of Qin Ding Su Ku Quan Shu. Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=en&res=5222 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Drucker, Peter. 2000. The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Chaohui. 2011. “三纲”真的是糟粕吗?—重新审视 “三纲”的历史与现实意义 “San Gang” Zhen De Shi Zao Po Ma? Chong Xin Shen Shi “San Gang” De Li Shi Yu Xian Shi Yi Yi. 天津社会科学 Tian Jin She Hui Ke Xue 2: 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Chaohui. 2014. “三纲”与秩序重建 San Gang Yu Zhi Xu Chong Jian. Beijing: Zhong Yang Bian Yi Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, Edmund S. K. 2010. The Intellectual Foundations of Chinese Modernity: Cultural and Political Thought in the Republican Era. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Fei. 2000. 韩非子新校注 Han Fei Zi Xin Jiao Zhu. Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- He, Yan. 1792. 論語集解義疏 Lun Yu Ji Jie Yi Shu. 欽定四庫全書本 The Version of Qin Ding Su Ku Quan Shu. Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&res=5095&remap=gb (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Hunter, Jeremy, and J. Scott Scherer. 2010. Knowledge Worker Productivity and the Practice of Self-Management. In The Drucker Difference: What the World’s Greatest Management Thinker Means to Today’s Business Leaders. Edited by Craig Pearce, Joseph Maciariello and Hideki Yamawaki. New York: McGrawHill, pp. 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Youwei. 2007. 致教育总长范静生书 Zhi Jiao Yu Zong Zhang Fan Jing Sheng Shu. In 康有为全集 Kang You Wei Quan Ji. Beijing: Zhong Guo Ren Min Da Xue Chu Ban She, vol. 10, pp. 321–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Takeo. 2017. The Crisis of Capitalism and the Gapponshugi of Shibusawa. In Ethical Capitalism: Shibusawa Eiichi and Business Leadership in Global Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 170–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Anguo, and Yingda Kong. 1992. 尚书正义 Shang Shu Zheng Yi. Beijing: Bei Jing Da Xue Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Kongzi (Confucius). 2003. Confucius Analects with Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Translated by Edward Slingerland. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kuok, Robert. 2017. Chinese—The Most Amazing Economic Ants on Earth: The Robert Kuok Memoirs. South China Morning Post. November 26. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/2121085/chinese-most-amazing-economic-ants-earth-robert-kuok-memoirs?module=perpetual_scroll&pgtype=article&campaign=2121085 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Lee, Shu-shan. 2020. “What Did the Emperor Ever Say?”—The Public Transcript of Confucian Political Obligation. Dao: A Journal of Comparative Philosophy 19: 231–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkletter, Karen E., and Joseph A. Maciariello. 2010. Management as a Liberal Art. In The Drucker Difference: What the World’s Greatest Management Thinker Means to Today’s Business Leaders. Edited by Craig Pearce, Joseph Maciariello and Hideki Yamawaki. New York: McGrawHill, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lufrano, Richard John. 1997. Honorable Merchants: Commence and Self-Cultivation in Late Imperial China. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ornatowski, Gregory K. 1996. Confucian Ethics and Economic Development: A Study of the Adaptation of Confucian Values to Modern Japanese Economic Ideology and Institutions. Journal of Socio-Economics 25: 571–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornatowski, Gregory K. 1998. On the Boundary between “Religious” and “Secular”: The Ideal and Practice of Neo-Confucian Self-Cultivation in Modern Japanese Economic Life. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 25: 345–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagers, John H. 2018. Confucian Capitalism: Shibusawa Eiichi, Business Ethics and Economic Development in Meiji Japan. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Shibusawa, Eiichi. 1996. 论语与算盘 Lun Yu Yu Suan Pan. Translated by Wang Zhongjiang. Beijing: Zhong Guo Qing Nian Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, Masakazu. 2017. The Entrepreneur Who Built Modern Japan: Shibusawa Eiichi. Translated by Paul Narum. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Bin. 2016. Is Confucius a Confucian? HUFFPOST. September 2. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/a-catechism-of-confuciani_6_b_9178068 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Song, Bin. 2018a. A Study of Comparative Philosophy of Religion on “Creatio Ex Nihilo” and “Sheng Sheng” (Birth Birth, 生生). Ph.D. Dissertation, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, July 27. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Bin. 2018b. Confucianism, Gapponshugi, and the Spirit of Japanese Capitalism. Confucian Academy (English-Chinese Bilingual) 4: 73–85, 176–88. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Bin. 2019. A Review of Confucianism for a Changing World Cultural Order. Reading Religion: A Publication of the American Academy of Religion. Edited by Roger Ames and Peter Hershock. January 30. Available online: http://readingreligion.org/books/confucianisms-changing-world-cultural-order (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Song, Bin. 2021. The Utopian Seed of Modern Chinese Politics in Ruism (Confucianism) and its Tillichian Remedy. In Why Tillich? Why Now? Edited by Thomas Bandy. Macon: Mercer University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Anna. 2013. Confucianism as a World Religion: Contested Histories and Contemporary Realities. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Anna. 2020. To Be or Not to Be a Confucian: Explicit and Implicit Religious Identities in the Global Twenty-First Century. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 11: 210–35. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, Tony. 2017. Confucianism in China: An Introduction. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Kazuhiro. 2017. Harmonization between Morality and Economy. In Ethical Capitalism: Shibusawa Eiichi and Business Leadership in Global Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Ssu-yu. 1943. Chinese Influence on the Western Examination System. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 7: 267–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turriago-Hoyos, Alvaro, Ulf Thoene, and Surendra Arjoon. 2016. Knowledge Workers and Virtues in Peter Drucker’s Management Theory. SAGE Open 6: 2158244016639631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xunzi. 2014. Xunzi: The Complete Text. Translated by Eric L. Hutton. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Ying. 2016. Confucian Image Politics: Masculine Morality in Seventeenth-Century China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xuan, and Yingda Kong. 1999. 礼记正义 Li Ji Zheng Yi. Beijing: Bei Jing Da Xue Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, B. Contemporary Business Practices of the Ru (Confucian) Ethic of “Three Guides and Five Constant Virtues (三綱五常)” in Asia and Beyond. Religions 2021, 12, 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100895

Song B. Contemporary Business Practices of the Ru (Confucian) Ethic of “Three Guides and Five Constant Virtues (三綱五常)” in Asia and Beyond. Religions. 2021; 12(10):895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100895

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Bin. 2021. "Contemporary Business Practices of the Ru (Confucian) Ethic of “Three Guides and Five Constant Virtues (三綱五常)” in Asia and Beyond" Religions 12, no. 10: 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100895