Abstract

Understanding the restrictions placed on religious institutions and associations, or the freedoms that they are denied, is essential for understanding the limits placed on individual religious freedoms and human rights more generally. This study uses the Religion and State round 3 (RAS3) dataset to track restrictions faced by religious organizations and individuals between 1990 and 2014 and explores how reduced institutional freedoms results in fewer individual freedoms. We find that restrictions on both institutional and individual religious freedoms are common and rising. Restrictions on institutional religious freedom are harsher against religious minorities than restrictions on individual freedoms. However, against the majority religion, restrictions on individual religious freedoms are harsher.

1. Introduction

Human rights are by definition focused on the individual.1 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that “…the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women2...” As a result, the UN and other organizations monitoring these rights tend to focus on individual rights and freedoms, such as the freedom of expression and thought, freedom of movement, ability to own property, adequate living and working conditions and the right to a host of civic, political and educational rights. Although human rights documents and activities acknowledge the importance of freedom of assembly and association for the individual, they give little attention to the freedoms of the associations where the individuals are assembling3.

Despite this extensive focus on individual rights, securing and protecting the rights of individuals relies on institutions and organizations receiving freedoms of their own. The most obvious are the multitude of Human Rights Organizations (HROs) who advocate for specific rights and monitor the activities of states and other institutions in supporting these rights. However, political parties, worker groups, voluntary associations and many other organizations are critical both for securing and protecting these rights. We argue that understanding the restrictions these associations face, or the freedoms that they are denied, is essential for understanding human rights more generally.

Recognizing the restrictions placed on religious institutions is especially critical for understanding the limits placed on individual religious freedoms. Because the individual’s practice of religion is often dependent on religious institutions and because religious institutions hold varied relationships with the state and surrounding culture, the religious freedoms of individuals are frequently intertwined with the freedoms of religious institutions. We acknowledge, of course, that all human rights are dependent on institutional support. Yet, we argue that for religion the relationship between institutional rights and individual rights is more tightly interwoven and is in need of exploration

Relying on data from the Religion and State round 3 (RAS3) collection, we will document the restrictions faced by religious organizations and individuals, chart these restrictions over time, and offer a global profile of where they are most common. Before we explore the data, however, we review the distinctive relationships religious institutions hold with the state and larger culture, we explain how this contributes to increased restrictions, and we explore how reduced institutional freedoms result in fewer individual freedoms.

2. Motives for Restricting Institutional Freedoms

Although the motives for restricting institutional religious freedoms (IRF) are varied, many of the motives arise from the distinctive relationships religion holds with the state and larger culture. Many of these motives are related to perceived threats. Religious alliances with the state, institutional competition between religions, competition with secular institutions, security risks, and ethnic, political, and national ties can all provide motives for restricting religious institutions.

One of the most common threats is the religious and cultural competition that minority religions pose for the dominant religion. Past research has established that dominant religions often seek an alliance with the state that provides increased support for their religion and increased restrictions on their religious competitors (Gill 2008, pp. 45–47; Stark and Finke 2000, pp. 199–200; Grim and Finke 2007, pp. 50–51; Finke 2013, pp. 300–1). Muslim-majority countries supporting a strict version of Sharia law provide the most obvious examples today, but all world religions form these alliances with the state. The government’s financial, legislative and legal support of the dominant religion and a diverse array of restrictions placed on minority religions are designed to increase the dominant religion’s competitive advantage. For adherents of the minority religions, however, these restrictions curtail or completely prevent individuals from openly practicing their religion.

Even when the dominant religion fails to hold a strong formal alliance with the state, the dominant religion and larger culture can restrict the activities of minority religious institutions. Non-state actors have enforced severe and sometimes violent restrictions on minority religions. In India, for examples, Muslims have been the most frequent targets of mob violence and killings by non-state actors, such as “cow vigilante” groups. Yet, no religious minority is exempt. During 2019 alone, Christians and Christian institutions in India were the target of 366 documented acts of violence or harassment. These actions included 7 churches being demolished or burned and 62 worship services being stopped4. Motivated to restrict the religious, political or cultural influence of religious minorities, non-state actors curb the activities of religious organizations through vandalism, persecution of clergy, refusing to lease to a specific religious group, or denying adherents access to an existing religious structure. However, societal-based discrimination against religious minorities far more often targets members of the minority rather than institutions specifically (Fox 2020, pp. 56–88).

The perceived threat of religious institutions, however, is not limited to minority religions or religious competition. The state holds many secular motives for restricting religions and often restricts majority religious institutions (Fox 2015, pp. 105–35). In extreme cases, the state holds a secular ideology that is formally opposed to religion. Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1979) sought to eliminate all religions in China and the former Soviet Union aggressively promoted a scientific atheism opposed to religion (Froese 2008; Yang 2012). Remnants of these policies remain in many communist and former communist nations, with restrictive registration requirements often preventing many religions from formally existing or openly meeting. In the case of China, heavy restrictions remain on all religions (Yang 2006, pp. 96–99; 2012, 85–122; Grim and Finke 2011, pp. 135–40). Yang (2019) reports that “since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, militant atheism has prevailed as national policy.” The oppressive treatment and ban of Falun Gong (Richardson and Edelman 2004, pp. 370–2), the aggressive campaign against Christian house churches (Yang 2019), and the destruction of thousands of Uighur Muslims mosques are the most obvious examples5 (Auslin 2019a, 2019b). China does allow some state-sponsored religious institutions for Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, Buddhists, and Taoists but these organizations face extensive approvals, requirements, and ongoing monitoring of their public worship.

Secular motives for restricting the activities of all religious institutions, however, are not limited to a few communist or former communist nations. Just as religions can compete with each other for political privileges, secularism as an ideology has become a political competitor to dominant and minority religions alike. Fox (2015, p. 28) explains that political secularism advocates that “religion ought to be separate from all or some aspects of politics and/or public life.” This form of secularism comes in many forms. The more passive forms require that religion remain out of government and that the state either does not interfere with religion or does so equally for all religions. The more assertive forms among democracies, as practiced in France, bans state support of any religion and places strong restrictions on the presence of religion in public spaces. Stressing that religion should be limited to the private realm, the more assertive forms of secularism advocate for more restrictions on religious institutions in the public realm (see Kuru 2009; Fox 2015). In non-democracies, anti-religious ideologies can result in even more severe restrictions (Philpott 2019).

Finally, religious institutions can be viewed as security risks by the state (Lausten and Wæver 2003; Cesari 2013; Chebel d’Appollonia 2015). Because religious institutions are centers of religious rites and devotion, they have proven effective at securing a commitment that surpasses nationality or loyalty to the state. As social institutions with an active membership, they have proven effective at mobilizing group action (Finke and Harris 2012; Djupe and Neiheisel 2018; Wald et al. 2005). The perceived risk is heightened still further when religion serves as a marker of long-standing ethnic, racial and national struggles between groups. Regardless of the actual threat, long-standing prejudices and perceived threat can fuel more restrictions against religious institutions (Fox 2020; Fox and Topor 2021). Previous work has found that security concerns are often used in Western countries to justify increased restrictions against Muslim minorities (Fox et al. 2019).

The distinctive relationship religious institutions hold with the state and larger culture, and the perceived threats they can pose to other institutions, results in distinctive societal and state pressures for restricting these institutions. These restrictions, however, have significant consequences on the religious freedoms of individuals.

3. Institutional and Individual Religious Rights

Social scientists have long acknowledged the interconnectedness of different levels of analysis (Emerson 1962; Coleman 1986). Just as social institutions and structures are the product of individual actions and beliefs, the expectations and demands of social institutions can shape the behavior and beliefs of individuals. Moreover, the state and larger culture can restrict and shape the actions of both the institution and the individual. This interplay between the different levels of analysis is clearly evident when studying religion (Finke 1990; Stark and Finke 2000). Religious institutions hold distinctive relationships with individuals, the state and the larger culture. Relationships that highlight why understanding the freedoms of religious institutions is critical for understanding the religious freedoms of individuals.

Unlike HROs mobilized to support specific rights related to equality or quality of life, religious institutions are the source of many of the religious practices being promised to individuals. This is especially important for the Abrahamic religions where routine public worship and prayer with a local gathering of fellow members is considered an essential requirement for religious practice. Practicing the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths includes social and group components that typically rely on institutional supports. For Jews, the weekly Shabbat includes public worship conducted in a temple or synagogue and led by a rabbi. Christian groups typically host worship services at least once each week that often includes a Eucharistic ritual conducted by an ordained pastor or priest. For Muslims, the Friday noontime prayer, the Jumah, is a congregational event hosted by the Imam and held at the mosque. Many devout Jews and Muslims also participate in communal prayers multiple times a day. The individual adherents for each of these groups relies on the religious institutions to organize and authorize these group activities. Even non-Abrahamic religions, which often place less emphasis on group activities, rely on temples or other institutions to provide sacred spaces and religious services for individual adherents. Thus, the practice and protection of many individual religious freedoms requires protecting the freedoms of religious institutions (Zhang 2020).

Beyond the routine religious activities, individuals also rely on religious institutions and their clergy to authorize and supervise rites of passage. In Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism the rites are referred to as Sanskara and vary in number both within and across the religious traditions. Catholic Christians have defined seven of the rites as sacraments and other Christians treat many of these rites with a similar reverence. Likewise, Muslims and Jews have specific ceremonies and rituals for performing these rites of passage. Virtually all world religions provide individuals with sacred rites related to birth and naming, marriage, death, entering adulthood and multiple other life events. Each of these ceremonies typically rely on the larger religious community. As a result, restricting the freedoms of religious institutions and their clergy denies individuals access to some of the most cherished and sacred religious rites during the life course.

Just as individuals rely on religious institutions for some of their most valued rituals and activities, religious institutions rely on the state and larger culture for their own freedoms. Because institutions include a formal organizational structure and often a place of worship, they are easier to locate and regulate than individual beliefs and behavior. Government registration requirements offer one example (Sarkissian 2015). Past research has established that this is one of the most pervasive methods for restricting and monitoring religious institutions. Registration requirements have increased sharply over the past two decades and a growing number of the requirements severely limit the activities of religious institutions and often threaten their survival (Finke et al. 2017). As the data will reveal, however, this is only one of many institutional restrictions.

The public presence of all religious institutions makes them a highly visible target for state or societal efforts to control religion. Regardless of the methods or the motives for restricting religious institutions, however, the end result is the same: both institutional and individual freedoms are denied. When restrictions are placed on religious institutions ability to operate openly and publicly, restrictions are also placed on the individual’s religious freedoms. Relying on the RAS3 collection, we will document the restrictions placed on institutions and explore how they are related to individual freedoms.

4. Measuring Institutional Religious Freedom (IRF)

This study relies on the Religion and State round 3 (RAS3) dataset to measure institutional religious freedom (IRF). Initially designed to measure government religion policy, the third round of this collection contains a large number of variables measuring restrictions on IRF. A university-based project, this collection draws its information from multiple sources including academic publications, human rights organization reports, government sources such as the US State Department Religious Freedom Reports, reports from multi-state organizations such as the UN and EU, and media sources. (Fox 2015, 2020) All variables are coded yearly for the 1990–2014 period6.

RAS3 divides limitations on religious freedom (both IRF and other types of religious freedom) into two categories: religious discrimination against religious minorities and the regulation of majority religions. Religious discrimination measures “restrictions on the religious practices and institutions of religious minorities which are not placed on the majority religion.” (Fox 2019, pp. 15–16) Religious regulation measures “the regulation of the majority religion (such regulations are usually also applied to minority religions).” (Fox 2019, p. 16). Fox (2015, pp. 136–39) points out that these are distinct because the motivations for restricting minority religions can be very different from those for restricting a majority religion or all religions in a country. For example, North Korea restricts all religions in the country and Saudi Arabia restricts all religions other than the state supported brand of Islam. In both countries Christians, for example, are heavily restricted but for very different reasons. In addition, while in theory, all of the types of discrimination and restrictions could apply to both categories, in practice, the manner in which governments restrict majority and minority religions differ. Accordingly, while there is some overlap between these two categories, many items in each category are different from those in the other category.

In order to sort out which types of restrictions and discrimination also constitute restrictions on IRF, it is important to define what IRF means specifically. As all RAS variables measure government policies which restrict either religious minorities or the majority religion, this definition must be a practical one which refers to exactly what government actions would constitute restrictions on IRF. We argue that four categories of government action fit this description.

First, restrictions directly on religious institutions or clergy. We include clergy in this category because clergy are central to the operation of religious institutions, often represent religious institutions, and can be considered an element of religious institutions in and of themselves. This is perhaps the most straightforward of these categories. Actions such as banning a religious institution or restricting a minority’s access to clergy are clearly actions which in some way limit religious institutions and are therefore violations of IRF.

Second, restrictions on institutions associated with religious institutions. These institutions have a strong connection to religion but are not necessarily churches, mosques, synagogues or temples. This can include religious educational institutions. It can also involve other forms of associations such as religious political parties and trade unions.

Third, restrictions on religious activities that are by their nature communal and often occur under the umbrella of religious institutions. This can include a wide variety of activities such as communal prayer, weddings, funerals, religious rites of passage, and religious publications. Of course, all of these activities can take place outside of the context of religious institutions. However, they are also all activities that not only often occur in the context of religious institutions, it is arguable that it is a central task of religious institutions to perform and facilitate these religious activities.

Such religious activities also include religious speech in the context of religious institutions. This can include language considered “hate speech” in some countries because many central precepts of major religions can be contrived as hate speech such as religious bans on homosexuality, for example. However, this speech must be by clergy or in the context of a religious institution.

Fourth, restrictions on political speech or political activities by clergy or religious institutions. While this strictly does not restrict religion itself, it does undermine the independence of religious institutions. To ban a religion from participating in politics prevents the religious institution from representing its interests to the government and the people, which can undermine its ability to act independently.

Based on these criteria, 19 of the 36 types of discrimination against religious minorities constitute violations of IRF and 19 of the 29 types of religious restrictions violate IRF. We discuss each of these in detail in the following section.

5. How Common Is Discrimination against Religious Minority Institutions?

Overall discrimination against the institutions of religious minorities is very common. In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, 79.2% of countries restricted the IRF of at least one religious minority. These violations of IRF are found across world regions and major religions. We will focus on general trends and findings in Table 1 below, but more detailed findings by world religion and region can be found in Table A1 of our Appendix A.

Table 1.

Types of Institutional Discrimination against Religious Minorities, 1990–2014.

5.1. Worship and Gatherings

Virtually all religious institutions support some form of communal worship or prayer and most try to devote a sacred space or building for their gatherings. Yet, for religious minorities these buildings and gatherings face some of the most frequent restrictions. Below and in Table 1 we review some of the most common forms of institutional religious discrimination (IRD) that minority religions face and document the sharp rise in most forms of IRD between 1990 and 2014. During the 25 years of the data collection, 17 of the 19 measures in the RAS3 collections increased and the increase was statistically significant for ten of these measures.

The most common form of IRD is restrictions on the building, leasing, or maintaining of places of worship, which was present in 41.5% of countries in 1990 and increased to 51.9% by 2014. While in some cases these restrictions are overt national policy, in Western countries such as Andorra, Australia, Austria, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Malta, Spain, and the United States, they are most often due to local governments denying the necessary building and zoning permits.

Registration requirements and restrictions are the second most common form of IRD and were present in 39.9% of counties in 1990, increasing to 44.8% in 2014. This is a particularly important form of IRD because denial of registration is a common governmental tactic to restrict minority religions. (Finke et al. 2017; Sarkissian 2015, pp. 33–34) It becomes particularly important when three conditions are present, (1) registration is required, (2) registration is sometimes denied, and (3) unregistered religious organizations are restricted. For example, in Eritrea all religious groups must renew their registration each year and many are denied. Religious practice by unregistered religions is illegal and often leads to arrest and imprisonment. The government often shuts down unregistered places of worship and breaks up meetings of unregistered religious groups which take place in private residences and sometimes seizes property form those residences7.

Denial of access to existing places of worship is also common and present in 21.9% of countries in 1990 and 32.8% in 2014. In many former Communist countries this is because properties seized in the Communist era have yet to be returned. For example, in Bulgaria this applies to many Muslim, Jewish and Catholic places of worship. This type of restriction becomes more severe when, as is the case in Bulgaria, it is combined with the previous one. In Bulgaria denial of permits was particularly hard on Jehovah’s Witnesses and Muslims. In 2009 a change in zoning plans invalidated a previously approved permit for Jehovah’s Witnesses to build a house of worship. Requests to build a second mosque in Sofia were delayed from 2002 until 2009 when the request was formally denied. In July 2011 the Supreme Administrative Court confirmed an order for the destruction of a mosque’s minaret, at the expense of the mosque, that authorities declared was a separate building and needed an additional construction permit8.

In 2014, 33.9% of the countries restricted the public observance of religion up from 27.9% in 19909. These restrictions are often closely tied to the registration requirements reviewed above. For example, a 2009 law in Armenia requires that all religious organizations have a minimum of 500 members to register. In addition, Armenia’s Criminal Code (Article 162) outlaws the establishment of religious organizations which inflict damage to individuals’ health, impact others’ rights or encourage refusal to perform civic duties10 (see section on conscientious objectors). This law is used to effectively ban a number of religious organizations including the Jehovah’s Witnesses. As a result, these organizations are severely limited in their ability to maintain places of worship and engage in public ceremonies and prayer.

Restrictions on private religious observance are less common and were present in 11.5% and 18.6% of countries in 1990 and 2014 respectively. Like a number of Muslim-majority countries Morocco often breaks up meetings of Christians in private homes. For example, in 2010, government agents raided a meeting of Christian citizens who were arrested and confiscated computers, phones, and Bibles. While they were eventually released without charges their possessions remained in police custody and a foreign resident was deported on charges of proselytizing to Muslims11.

Banning or placing restrictions on religious organizations nearly doubled between 1990 (19.1% of countries) and 2014 (37.9% of countries). In many cases this type of restriction is placed on organizations that the government considers extremist, dangerous or violent. For example, while in 2013 the German government took several steps to recognize and formalize its relationship with mainstream Islamic organizations, in the same year the government banned several Muslim groups. The government considered these groups anti-democratic and pro-jihad. Some of them were accused of plotting to murder right-wing activists who displayed cartoons of Muhammad and were linked to a gunman who killed US airmen in Germany. Some of their leaders were arrested. This took place in the context of surveillance of a larger number of “suspect” Islamic groups12. In other countries such as Saudi Arabia and the Maldives, this represents a wholesale ban on any minority religious organization.

Finally, many countries ban or restrict religions that they consider cults. In 1990 this occurred in 12% of the countries and increased to 21.3% by 2014. During this period, Angola, Austria, Belgium, China, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, Italy, Kenya, Russia, Rwanda, Togo, and Uganda all passed laws or otherwise began a policy of restricting or banning at least one religion they consider a cult. There is little agreement in both politics and academia on the definition of the term “cult.” Academic definitions focus on a cult’s small size, dangerous or violent practices and the presence of a charismatic leader. (Almond et al. 2003, pp. 91, 103; Appleby 2000, p. 204; Grim and Finke 2011, pp. 47–48) Anti-cult policies tend to focus on religions which are small and new to a country. As Thomas (2001, p. 529) puts it, “there is…[an] informally defined universe of acceptable religions and spiritualties. Those which fall outside this universe are stigmatized as cults”.

5.2. Religious Rites

Local religious institutions, and the buildings they often support, are most frequently used for worship, prayer and other communal activities that occur on a routine basis. As noted earlier, however, some of the most valued rituals are the rites that consecrate an important stage in the life course. These religious rites frequently rely on the sacred space, authorized clergy and communal support of the local religious institution. As a result, some religious rites are limited or outlawed due to more general restrictions on the religious group or their clergy. A few of the RAS3 measures, however, identify restrictions on specific religious rites.

Marriage is a ceremony often performed in places of worship and for many religious people divorce is not possible outside of religious auspices. While restrictions on the observance of religious marriage and divorce laws dropped from 12.6% of countries in 1990 to 12.0% in 2014, this type of restriction is still present in one out of 8.3 countries. For example in India marriage and divorce laws follow those of a person’s religion. Sikhism, Jainism, and Buddhism, despite being distinct religions with their own traditions including those related to marriage and divorce, are considered by the government to be subsets of Hinduism. Thus, under Indian law, members of these religions are subject to the marriage and divorce laws of a religion other than their own. However, in 2012, the Parliament passed a law that permits Sikhs to register their marriages under their own laws. This law does not extend to divorce13.

Most religious people prefer to be buried under the auspices of their own religion. This right was restricted on 17.5% of countries in 1990, increasing to 21.3% in 2014. In Greece the law requires exhumation of bodies after three years. This violates Islamic religious law. Most Greek Muslims are buried in Thrace, where due to treaty obligations with Turkey, an exception is made, or in their country of origin. The Thrace Muslim community reported that some of their cemeteries were not maintained, as required by law14. Additionally, several religions include cremation in their burial rites. Until 2006 cremation was illegal in Greece. Since then, no crematory facilities have been established due to Greek Orthodox Church officials’ objections15.

Restrictions on circumcisions and other religious rites of passage are far rarer and were only present in three countries in 2014. As Fox (2020, pp. 155–56) notes:

Since 2001 Sweden regulates male circumcision. Circumcision of male infants must be performed by a licensed doctor or if someone certified by the National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW) attends. The NBHW has certified mohels (persons trained to perform the Jewish ritual of circumcision) to perform circumcisions but they may do so only in the presence of an anesthesiologist or other medical doctor. This places a significant burden on performing the ritual. Denmark passed a similar law in 200516 as did Norway in 2014.

In practice in these countries, a rite that most Jews had previously practiced in synagogues was moved to medical clinics in order to avoid violating these laws.

5.3. Other Institutional Operations

Beyond providing support for communal worship, prayer and rites of passage, the institutions of religious minorities are frequently involved in education and publication. Both practices are often limited by registration requirements and both face even more resistance when they are tied to a nation or a larger international community not supported by the state. Table 1 offers a few examples from RAS3.

Once again, the restrictions showed a sharp increase from many of the measures. Restrictions on religious schools and education increased form being present in 15.3% of countries in 1990 to 23.0% in 2014. For example, Hungary’s 2011 Religious Freedom act required all religious organizations to re-register. While most mainstream organizations successfully registered, many smaller groups were denied registration. As a result many of their activities have been curtailed. This includes the closing of several religious schools17.

Restrictions on disseminating and importing religious publications, including primary religious texts such as the Bible or Koran, also increased. By 2014, 26.2% had restrictions on the writing and disseminating of religious publications and 21.3% restricted the importing of religious publications. For example, in Vietnam all religious publications must be published and approved by the State Publishing House’s Office of Religious Affairs, or by other government-approved publishing houses. Officially unregistered religions are not allowed to publish. However, in practice, some private, unlicensed publishing houses were able to unofficially print and distribute religious texts18. Although mentioned less frequently, countries also had restrictions on religious materials other than publications. These restrictions were present in 6.6% of the countries in 1990 and 8.1% in 2014.

5.4. Clergy and Institutional Voice

Religious institutions are the most visible target for state action against minority religions and the clergy are the most visible target within the institution. As the authorized leaders for performing rites and leading worship and prayers, they serve as representatives for the larger religious group. In many cases, they are the voice of the religious institution. This authority, visibility and voice, however, also makes them frequent targets for restrictions. Restrictions that attempt to control who can become clergy and what they can do as clergy.

Restrictions on ordination and access to clergy increased modestly from 15.8% in 1990 to 18.6% in 2014. One example is Denmark’s so-called “Imam Law” enacted in 2004. While the law was written broadly to apply to foreign clergy of all religions, in practice it is targeted against Muslim clergy. The law requires that the number of religious residence visas issued to foreign clergy should be proportional to the size of the religious community. It also requires that the applicant be associated with a recognized religion, possess a proven relevant background for religious work and be self-financing. The legislation denies a visa if there is “reason to believe the foreigner will be a threat to public safety, security, public order, health, decency or other people’s rights and duties”, alluding to Imams who preach ideas contrary to Danish cultural norms19. In the Netherlands, all imams and other spiritual leaders recruited in Islamic countries must complete a year-long integration course before being allowed to practice20. Since 2005 in the UK, the government can exclude individuals, including religious leaders, from the country if they have engaged in “unacceptable” behavior. The government defines unacceptable behavior as using any means, including religious expression, to express views that foster extremism or hatred21.

Restrictions on clergy access to jails, hospitals, and the military increased modestly as well. In 1990 26.4% of governments limited access to at least one of these spaces for at least some minority clergy, when compared to clergy from the majority religion. This increased to 30.1% by 2014. Russia restricts access to all three. Only registered organizations can provide clergy to hospitals and jails, and Russia regularly denies registration to a wide variety of religions. In the military, even registered organizations may provide chaplains only if members of their religion constitute 10% or more of a unit. In numerous cases, where Muslims were more than 10% of a unit, access to Muslim clergy was still denied. In addition the Russian Orthodox Church is given preferred access to all of these institutions. In prisons, nearly all chaplains are from the Russian Orthodox Church22.

The arrest, dentition, and harassment of religious minorities often focuses on clergy and increased from being present in 21.3% of countries in 1990 to 34.4% in 2014. China, for example, supports five state-sponsored religious organizations for Catholics, Protestants, Muslims, Buddhists, and Taoists. Any religious organization not under the auspices of one of these organizations is subject to closure by the government and clergy for these organizations are regularly harassed, detained, and imprisoned. Because many religious groups, including most Christian congregations, are not state approved, the clergy of these groups are frequent targets. A trend that increased following China’s revision of the “Regulations of Religious Affairs” in 2018 (Yang 2019).

5.5. Comparing Institutional and Non-Institutional Discrimination against Religious Minorities

Each of the measures reviewed above documents how institutions of religious minorities face discriminatory restrictions that are not imposed on other religions. As noted earlier, however, restrictions on the freedoms of institutions results in restrictions on the freedoms of individuals. For religious institutions the link is especially close. The institutional restrictions reviewed above each challenge basic individual rights by limiting individuals’ ability to manifest their “religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance23.”

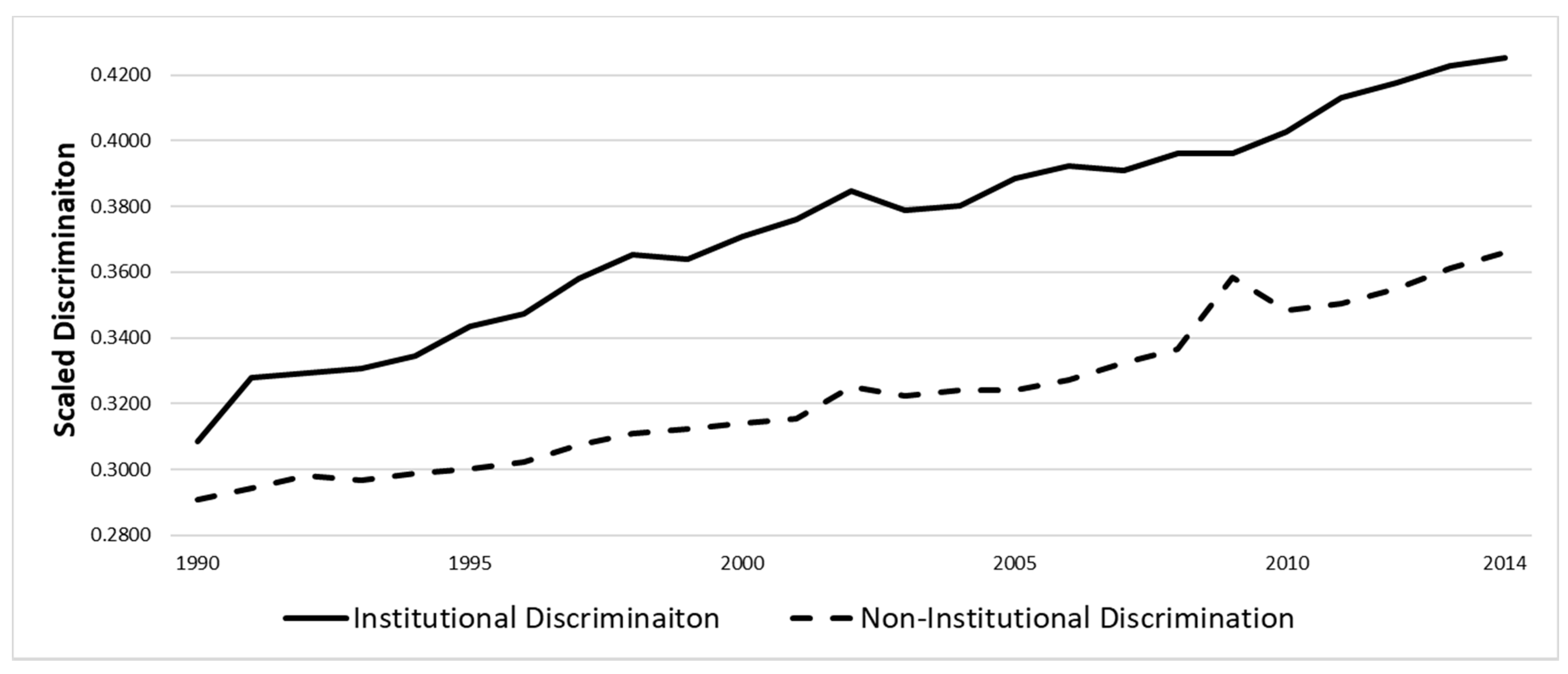

Figure 1 illustrates how closely these freedoms are related. Using standardized scores to allow for comparison, this figure charts the overtime trends for the summary measure of institutional discrimination against religious minorities and compares it to the summary measure for non-institutional discrimination against religious minorities. With few exceptions, they each show a continual increase overtime. Yet, the standardized score for institutional discrimination is consistently higher than non-institutional discrimination and the gap between the two measures increases overtime24. The two forms of discrimination are closely linked, though the institutions of religious minorities are proving to be the most frequent targets.

Figure 1.

Discrimination Against Religious Minorities, 1990–2014. Significance (t-test) between institutional and non-institutional <0.001 in 1990–2014. Significance (t-test) between institutional in 1990 and institutional <0.05 in 1996–1997, <0.01 in 1998–1999, <0.001 in 2000–2014. Significance (t-test) between institutional in 1990 and institutional <0.05 in 1993, <0.01 in 1994, and <0.001 in 1995–2014.

6. How Common Are Restrictions on All Religious Institutions?

When we look at all religious institutions, rather than limiting our attention to religious minorities, government restrictions remain high. Similar to religious minorities, IRF is on the decline for all religious institutions, with 18 of the 19 RAS3 measures showing an increase in institutional religious restrictions (IRR) over the 25 year collection. By 2014, 76% of countries imposed at least one of the restrictions on the majority religion, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Restrictions on All Religious Institutions, 1990–2014.

Despite their favored status, even the majority religions face IRR, including their internal institutional activities and their activities in the public square. Indeed, in many countries the dominant religion faces careful monitoring of state requirements on their institutional practices and their clergy. Once again, we focus on general trends and findings, but more detailed findings by world religion and region can be found in Table A3 and Table A4 of our Appendix A.

6.1. General Requirements and Restrictions

A few types of IRR cover the general operation of institutions. These can range from blanket bans or restrictions on all religions to specific laws on what institutions are expected to teach or how they are organized.

Our first item, restrictions on formal religious organizations, measures restrictions placed on formal religious organizations such as churches, mosques, and synagogues as well as larger religious associations meant to represent the interests of religious denominations. This is a restriction that generally applies to all organizations including and especially the mainstream majority religious organization and was present in 12.0% of countries in 1990, increasing to 16.2% by 2014. Perhaps the most extreme case of this phenomenon is North Korea which bans all religious organizations. While the government created religious “federations” for Buddhists, Protestants and Catholics, former refugees and defectors attest that these federations are led by political operatives whose goals are to support and enforce the government’s policy of control over religious activity.

Other forms of influence over religious organizations are also common with 17.5% of governments doing so in 1990 increasing to 21.3% by 2014. This refers to forms of influence other than government influence over the appointment of clergy and government approval of religious laws. In some countries like Djibouti, this is due to general government control of all majority religious institutions. The Ministry of Islamic Affairs controls in Islamic matters, including mosques, private religious schools, and religious events, as well as general Islamic policy in the country. The ministry also coordinates all Islamic NGOs in the country25. In other countries, the control is less all-encompassing. For example, in Azerbaijan all registered Islamic organizations must provide a yearly report of their activities to the government26.

For some nations, the laws governing the state religion are passed by the government or require the government’s approval. These often cover key theological issues or address how religious institutions organize themselves. In 2014, 14.2% of governments engaged in this practice, up from 13.1% in 1990. In some cases, such as Iran and Gaza, the government and religious authorities are the same. In some cases the influence is less extensive. For example, Article 41 of Morocco’s constitution names the Superior Council of the Ulemas as the only body permitted to issue religious rulings (fatwas), which must be approved by the King.

Restrictions on non-state sponsored or supported institutions involves cases where there is a state-supported or recognized set of institutions for the majority religion and at least some alternative institutions are banned or restricted. This is becoming increasingly common. It was present in 15.3% of countries in 1990 and rose to 28.4% by 2014. This is particularly common in Orthodox Christian majority countries and mostly involves disputes within or between Orthodox churches. In Bulgaria, this is due to a dispute over the leadership of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church where the government supports one set of leaders and represses the “Alternative Synod.” Similarly in Russia the Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church does not accept the authority of the current leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church and is restricted by the Russian government. Montenegro supports the Montenegrin Orthodox Church which was established in 1993 at the expense of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Moldova similarly supports the Russian Orthodox Church and represses the Romanian Orthodox Church.

Finally, state ownership of religious property is a common means for restricting and controlling the majority religious institutions. This does not refer to chapels for religious services in government institutions such as military bases but, rather, religious property intended for use by the wider public. This policy was present in 25.7% of countries in 1990, increasing slightly to 26.8% in 2014. For example, the traditionally anti-clerical states of France and Mexico own most religious property in the country. In France, all religious buildings built before 1905 belong to the state based on its 1905 Law on the Separation of Church and State. Mexico’s 1917 constitution makes all religious property the property of the state. The constitution was amended in December 1991 removing a number of restrictions on religious institutions so all religious property built since 1992 now belongs to the association which built it.

Foreign religious organizations required a sponsor in 6.6% of countries in 1990, increasing to 8.7% by 2014. In Kazakhstan this is part of a broader set of restrictions on foreign religion in the country. All missionaries, nationals and foreign, must be associated with a registered religious association. Foreigners may not register religious groups and all signatories on religious registration applications must be citizens. Foreign religious associations must be given governmental approval for their activities in Kazakhstan.

6.2. Worship and Gatherings

Once again, we find that many of the restrictions on religious institutions are targeted at the core religious activities of worship and public gatherings. Some are aimed at the majority religion, but most apply to all religions. Many of the restrictions addressed the state’s concerns about religion in the public arena.

In 1990, 8.2% of governments restricted or controlled the observance of the religious practices of the majority religion in public. This increased to 12.6% by 2014. In some cases, such as Uzbekistan, this is due to government control of all religious activities. The government limits the number of legal religious institutions, bans all religious activities outside of them and controls all religious activities within them. In other countries the regulation is less onerous. For example, according to Latvia’s 1995 Law on Religious Organizations, religious organizations must coordinate public religious activities with the local municipalities in which they take place.

Religious organizations often organize religious activities outside recognized religious facilities. In 1990, 9.3% of countries restricted at least some such activities. This increased to 16.4% by 2014. In China, any religious activities which take place outside of state-sponsored religious institutions are illegal. Such unrecognized places of worship are shut down by the state. In other cases, the restrictions are not as absolute. In the Ukraine, for example, religious groups must apply at least ten days in advance for a permit to hold religious services, activities, and processions in public places outside of religious and burial sites27.

A few countries had specific restrictions on religious public gatherings not placed on other public gatherings. These restrictions are placed specifically on religious gatherings, even if the activities are not religious in nature, and not gatherings under other auspices. These restrictions were present in 4.4% of countries in 1990 and increased to 6.0% in 2014. For example, in 2014 Equatorial Guinea’s government decreed that any religious activities taking place outside the hours of 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. or outside of registered places of worship require government permission. The decree also prohibits religious acts or preaching within private residences and requires foreign religious representatives or authorities to obtain advance government permission to participate in religious activities28.

In a growing number of nations the government has restricted access to places of worship. This increased from 6.6% in 1990 to 10.4% by 2014. In Tajikistan, these restrictions are particularly harsh. Mosques, madrassas, and other houses-of-worship are routinely closed either due to “infractions of the law” or without explanation. Since 2007 this policy has escalated and many mosques, Muslim prayer halls, the country’s only synagogue in the capital Dushanbe, and Protestant churches have been closed, demolished, or confiscated without compensation. In 2013, Tajikistan’s government-controlled Council for Religious Affairs suspended the activities of seven of the country’s eight madrassas. Only one madrassa for students above the ninth grade continued to operate29.

6.3. Related Institutional Activities

Government concern for the role of religious institutions in the public arena is increasingly extending far beyond their worship and gatherings. For example, 6.6% of the countries now place restrictions on religious unions or trade associations. Portugal, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique each have constitutional provisions banning religious trade unions.

Far more common, however, are restrictions on religious political parties. These restrictions were present in 37.2% of states in 2014, a large increase from 23.5% in 1990. Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Brunei, Cambodia, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Djibouti, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Honduras, Israel, Kenya, Madagascar, Nigeria, Morocco, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Uganda all added this type of restriction after 1990. In some cases these restrictions were only against certain political parties. In Israel, for example, several religious political parties remain legal and are often members of the governing coalition. However, certain Jewish religious political parties deemed racist are banned. In other countries these new restrictions were broader. For example, Djibouti’s 1992 Constitution states that a political party is prohibited “to identify themselves to a race, to an ethnicity, to a sex, to a religion, to a sect, to a language or to a region.” Congo-Brazzaville, Gambia, and Ghana, among many other states, added similar constitutional provisions after 1990.

Although facing fewer restrictions than the minority religions, majority religions also faced restrictions on publishing and disseminating religious literature. These activities, which are core activities for many religious organizations, were restricted in 10.9% of countries in 1990 and 12.0% in 2014. Unsurprisingly, this is a common practice, at least to some extent, in Communist countries such as China, Cuba, Laos, Vietnam and North Korea. However, this type of ban can occur for reasons other than anti-religious ideology. In Indonesia, the 1978 Guidelines for the Propagation of Religion (Ministerial Decision No. 70/1978), seeks to reduce inter-religious tensions by banning proselytizing or dissemination of religious materials to people of another religion, use of material inducements to encourage conversion, and door-to-door missionary activity30.

6.4. Clergy & Institutional Voice

Once again, the visibility, leadership and voice of the clergy have been a significant concern for many nations. From clergy politics to clerical appointments and activities, state’s often attempt to monitor and control the clergy. The clergy of majority religions, or religions with a sizable following, are often of significant concern because they have the potential to mobilize more support. The RAS3 collection found restrictions on clergy in several key areas.

The message from clergy is most frequently heard in the form of a sermon and is increasingly receiving attention from governments. In 1990 21.3% of governments monitored, controlled, or restricted sermons given by clergy. By 2014 it increased to 27.3% of all nations. A number of Middle Eastern countries engage in this practice both to ensure that the sermons conform to the government-approved interpretation of Islam and in order to assure that the sermons do not oppose or criticize the government. These include Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, the Palestinian Authority, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, (pre-civil war) Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, and the UAE. Mexico, as part of its historical anti-clerical policies, bans clergy from expressing political views including in sermons.

The second most common form of IRR is restrictions on political activity by clergy or religious institutions. The use of these restrictions jumped from 23.5% of all countries in 1990 to 34.4% by 2014. Some of these restrictions are relatively mild. For example, in the US if a religious institution advocates for or against the election of a political candidate it can lose its tax status as a non-profit organization but advocating for or against particular policies is allowed. Other countries ban a wider range of activity. Costa Rica’s constitution, for example, bans religious political propaganda by clergymen and laymen. Similarly, in Singapore clergy may not engage in political activity or disparage the state.

In several countries, clergy violating state requirements incur stiff penalties. The arrest, detention, or harassment of religious figures, officials, or party members occurred in 10.9% of countries in 1990, increasing to 14.8% in 2014. This is largely limited to Communist states and former communist states that retain communism’s anti-religious approach, such as Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

For a few countries citizenship of the clergy was a concern. In 1990 the heads of the majority religious organization were required to be citizens in 7.7% of countries and in 2.2% all clergy were required to be citizens. By 2014 this increased, respectively, to 9.3% and 4.8%. For example, according to a 1978 law in Haiti only the Ministry of Worship can grant the titles of priest, pastor, or minister of a church. These titles can be granted only to Haitian citizens31. In most countries where these types of restrictions are present, they apply mostly to senior officials. For example, in Panama, all senior Church officials must be citizens32.

Finally, government appointment or approval of senior clergy is a common way to control or restrict religious organizations and in 2014 was present in 28.4% of countries, up from 25.7% in 1990. This is not uncommon in Western democracies with official religions such as Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg, and the UK. It is particularly common in the Middle East where all countries other than Iraq, Morocco, Qatar, and the Western Sahara engage in some form of this practice.

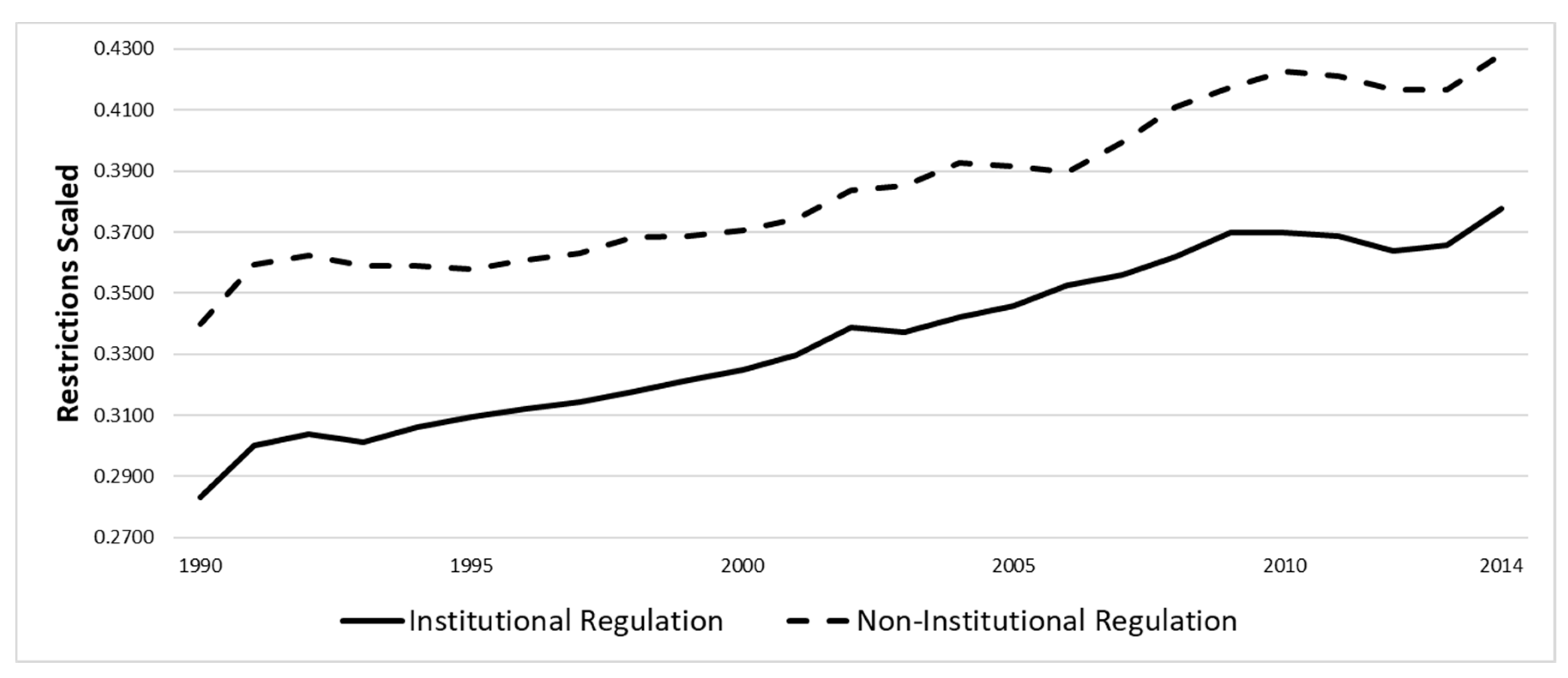

6.5. Comparing Institutional and Non-Institutional Restrictions on All Religions

Like the minority religions, there is a close link between IRR and individual religious freedoms for all religions. Using a summary measure for IRR and a summary measure of non-institutional restrictions, Figure 2 charts the trends overtime. Once again, we use a scaled score for each summary measure to allow for easy comparisons33. Like discrimination against religious minorities, the restrictions on all religions are rising for both institutional and non-institutional government restrictions. However, IRR is consistently lower than restrictions on the majority’s individual religious freedoms. Similar to Figure 1, the results suggest institutional and individual freedoms are closely linked, but individuals are the more frequent targets of government restrictions.

Figure 2.

Restrictions on All Religions, 1990–2014. Significance (t-test) between institutional and non-institutional, <0.001 in 1990–2014. Significance (t-test) between institutional in 1990 and institutional <0.05 in 1991, 1994, <0.01 in 1995–1996, <0.001 in 1992, 1997–2014. Significance (t-test) between institutional in 1990 and institutional <0.05 in 2001, <0.01 in 2002, 2004–2007, <0.001 in 2003, 2008–2014.

This has several implications. First, IRR occurs in the context of a wider variety of violations of religious freedom. Second, IRR is slightly less common than other violations of religious freedom against majority religions. Third, the rise in IRR demonstrates that it is an issue that is of increasing importance.

7. Conclusions

We have contended that an individual’s religious freedom is intimately tied to the freedom of religious institutions. Because religious institutions authorize and supervise rites of passage, support required communal worship and prayer, and dispense other highly valued religious goods, ensuring individual freedoms requires freedoms for the institutions. The complex and varied relationships that the state holds with religious institutions, however, often compromise the freedoms that these institutions receive.

Our review of the Religion and State round 3 data collection from 1990 to 2014 has uncovered several important trends and relationships for IRFs. First, both restrictions on institutional religious freedoms (IRF) and individual religious freedoms are on the rise. The findings suggest that restrictions on religious institutions inevitably have a significant influence on individual freedoms, with the two trends rising together over time. For IRF, the rise in restrictions increased for nearly all of the 35 measures included in RAS3. We found that 17 of the 19 measures on IRD increased from 1990 to 2014, and 18 of the 19 measures on IRR increased.

Second, despite rising in unison, we found interesting differences in the trends for institutional and individual religious freedoms. When dealing with minority religious institutions, restrictions on IRF are higher than those against individuals. However, when dealing with the majority religions, restrictions on individual freedoms are more common and severe than restrictions on IRF.

One potential explanation for this dynamic is that governments differ in how they attempt to control majority and minority religions. Whereas most countries have some form of connection with the majority religious institutions, and typically provide funding for these institutions, governments are far less likely to support minority religions. While in some cases government backing for the majority religion is due to a genuine desire to support, in others the motives are more clearly tied to controlling and limiting the majority religion. That is, supporting a religious institution is one of the most effective means of controlling it. (Fox 2015, pp. 65–67, 2019) In either case, this support lowers the desire or need to directly restrict the IRF of majority religious institutions. For minority religions, however, where government support is less prevalent, the withdrawing or increasing of institutional support is not an option. Instead, when the institutions of minority religions are seen as a potential threat to a regime, religion or culture, the response is to limit or eliminate the IRF of minority religions. (Koesel 2014; Sarkissian 2015).

In a larger view, this focus on IRF provides several insights that add perspective to the general topic of religious freedom. First, it highlights that the freedoms given or not given to religious institutions greatly impact upon the individual. Second, we demonstrate that the patterns of restrictions on IRF and individual religious freedoms differ. Discovering the reasons for these differing patterns is an important agenda for future research. Third, much of the existing research on religious freedom takes the perspective of individual freedoms and rights. Without in any way downplaying the importance of individual freedoms, our findings demonstrate that IRF requires more attention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and R.F.; Data curation, J.F.; Formal analysis, J.F.; Investigation, J.F.; Methodology, J.F.; Writing—original draft, J.F. and R.F. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Israel Science Foundation (Grant 23/14), The German-Israel Foundation (Grant 1291-119.4/2015) and the John Templeton Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The Religion and State Dataset is available at www.religionandstate.org.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Types of Institutional Discrimination against Religious Minorities, 1990–2014.

Table A1.

Types of Institutional Discrimination against Religious Minorities, 1990–2014.

| Restrictions on/Government Actions | All Countries | By Country Grouping in 201434 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2014 | EWNOCMD | Orthodox | Muslim | Communist | Buddhist | The Rest Democracies | The Rest Non-Democracies | |

| Worship & Gatherings | |||||||||

| Build, lease, or repair places of worship | 41.5% | 51.9% | 60.6% | 100.0% | 74.5% | 80.0% | 83.3% | 9.1% | 23.7% |

| Registration | 39.9% | 44.8% | 57.6% | 100.0% | 43.6% | 60.0% | 33.3% | 26.3% | 31.6% |

| Access to places of worship | 21.9% | 32.8% | 15.2% | 84.6% | 43.6% | 80.0% | 50.0% | 21.2% | 15.8% |

| Public observance | 27.9% | 33.9% | 9.1% | 53.8% | 60.0% | 80.0% | 50.0% | 9.1% | 23.7% |

| Private observance | 11.5% | 18.6% | 0.0% | 38.5% | 32.7% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 15.8% |

| Formal organizations | 19.1% | 37.9% | 15.2% | 30.8% | 41.8% | 100.0% | 16.7% | 15.2% | 21.1% |

| Anti-cult/sect laws | 12.0% | 21.3% | 30.3% | 38.5% | 18.2% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 15.2% | 15.8% |

| Religious Rites | |||||||||

| Religious marriage and divorce laws | 12.6% | 12.0% | 0.0% | 15.4% | 27.3% | 40.0% | 33.3% | 3.0% | 0.0% |

| Religious burial | 17.5% | 21.3% | 21.2% | 53.8% | 30.9% | 60.0% | 16.7% | 6.1% | 5.3% |

| Circumcision or rites of passage | 0.0% | 0.5% | 3.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Related Institutional Operations | |||||||||

| Religious schools/religious education | 15.3% | 23.0% | 18.2% | 46.2% | 36.1% | 80.0% | 50.0% | 3.0% | 5.3% |

| Import religious publications | 20.8% | 21.3% | 0.0% | 30.8% | 40.9% | 80.0% | 33.3% | 0.0% | 2.6% |

| Religious materials | 6.6% | 8.1% | 0.0% | 38.5% | 32.7% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 23.7% |

| Write/publish/disseminate rel. publications | 20.8% | 26.2% | 6.1% | 46.2% | 54.5% | 60.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 7.9% |

| Clergy & Institutional Voice | |||||||||

| Ordination/access to clergy | 15.8% | 18.6% | 18.2% | 38.5% | 23.6% | 100.0% | 50.0% | 3.0% | 3.6% |

| Clergy access to jails | 19.1% | 21.9% | 45.5% | 53.8% | 14.5% | 40.0% | 16.7% | 15.2% | 5.3% |

| Clergy access to military | 21.9% | 24.0% | 39.4% | 69.2% | 16.4% | 20.0% | 16.7% | 21.2% | 10.5% |

| Clergy access to hospitals | 13.1% | 15.3% | 39.4% | 53.8% | 7.3% | 20.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 2.6% |

| Arrest/detention/harassment | 21.3% | 34.4% | 21.2% | 53.8% | 56.4% | 100.0% | 50.0% | 9.1% | 18.4% |

| Mean scaled for comparison | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.24 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

Table A2.

Types of Non-Institutional Discrimination against Religious Minorities, 1990–2014.

Table A2.

Types of Non-Institutional Discrimination against Religious Minorities, 1990–2014.

| Restrictions on/Government Actions | All Countries | By Country Grouping in 2014 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2014 | EWNOCMD | Orthodox | Muslim | Communist | Buddhist | The Rest Democracies | The Rest Non-Democracies | |

| Forced observance of maj. religion | 14.2% | 19.7% | 0.0% | 7.7% | 4.18% | 40.0% | 66.7% | 18.2% | 5.3% |

| Religious publications for personal use | 8.7% | 13.7% | 0.0% | 15.4% | 36.4% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% |

| Dietary laws | 3.3% | 4.4% | 15.2% | 0.0% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.6% |

| Religious symbols | 9.8% | 16.9% | 33.3% | 30.8% | 14.5% | 20.0% | 16.7% | 6.1% | 10.5% |

| Conversion away from the majority religion | 14.2% | 15.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 45.5% | 20.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 0.0% |

| Forced renunciation of conversions | 7.1% | 8.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17.2% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 6.1% | 2.6% |

| Forced conversion | 3.3% | 6.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.7% | 40.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 2.6% |

| Conversion campaigns | 12.0% | 13.7% | 0.0% | 7.7% | 30.9% | 80.0% | 16.7% | 6.1% | 0.0% |

| Proselytizing by residents to majority rel. | 29.5% | 33.9% | 6.1% | 61.5% | 67.3% | 100.0% | 66.7% | 6.1% | 10.5% |

| Proselytizing by residents to minority rel. | 15.8% | 21.3% | 6.1% | 61.5% | 37.3% | 80.0% | 66.7% | 6.1% | 10.5% |

| Foreign proselytizers | 44.3% | 48.1% | 30.3% | 69.2% | 69.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 24.2% | 31.6% |

| Mandatory education in the maj. religion | 21.9% | 24.6% | 12.1% | 23.1% | 49.1% | 40.0% | 50.0% | 9.1% | 7.9% |

| Willful failure to protect from violence | 13.7% | 20.8% | 3.0% | 76.9% | 32.7% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 12.1% | 7.9% |

| Surveillance | 15.8% | 29.0% | 36.4% | 53.8% | 34.5% | 80.0% | 33.3% | 12.1% | 13.2% |

| Child custody granted based on religion | 12.6% | 15.3% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 45.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 0.0% |

| Anti-minority propaganda | 23.0% | 27.3% | 15.2% | 76.9% | 49.1% | 80.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 7.9% |

| Other forms of discrimination | 23.5% | 34.4% | 18.2% | 53.8% | 45.5% | 80.0% | 16.7% | 26.3% | 28.9% |

| At least one type | 67.2% | 77.6% | 69.7% | 100.0% | 87.3% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 66.7% | 65.8% |

| Mean | 4.97 | 6.22 | 2.40 | 7.62 | 12.33 | 18.20 | 8.17 | 1.88 | 2.13 |

| Mean scaled for comparison | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.44 | 0.73 | 1.07 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

Table A3.

Restrictions on All Religious Institutions, 1990–2014.

Table A3.

Restrictions on All Religious Institutions, 1990–2014.

| Restrictions on/Government Actions | All Countries | By Country Grouping in 2014 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2014 | EWNOCMD | Orthodox | Muslim | Communist | Buddhist | The Rest Democracies | The Rest Non-Democracies | |

| General Requirements and Restrictions | |||||||||

| Formal religious organizations | 12.0% | 16.2% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 38.2% | 80.% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 2.6% |

| Government influences religious orgs. | 17.5% | 21.3% | 6.1% | 23.1% | 49.1% | 80.0% | 33.3% | 3.0% | 0.0% |

| Government passes/approves laws governing state religion | 14.2% | 13.1% | 9.1% | 7.7% | 30.9% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 30% | 2.6% |

| Restrictions/harassment of non-state sponsored/recognized religious format | 15.3% | 28.4% | 0.0% | 61.5% | 63.6% | 40.0% | 16.7% | 6.1% | 10.5% |

| State ownership of some rel. property | 25.7% | 26.8% | 15.2% | 53.8% | 43.6% | 40.0% | 33.3% | 12.1% | 13.2% |

| Worship and Gatherings | |||||||||

| Public observance of religious practices | 8.2% | 12.6% | 9.1% | 7.7% | 14.5% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 9.1% | 10.5% |

| Rel. activities outside recognized facilities | 9.3% | 16.4% | 0.0% | 30.8% | 21.8% | 100.0% | 16.7% | 6.1% | 15.8% |

| Religious public gatherings not placed on other public gatherings | 4.4% | 6.0% | 3.0% | 0.0% | 5.5% | 40.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 7.9% |

| Access to places of worship | 6.6% | 10.4% | 6.1% | 23.1% | 16.4% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 2.6% |

| Foreign religious orgs. require sponsors | 6.6% | 8.7% | 0.0% | 23.1% | 9.1% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 12.1% | 7.9% |

| Related Institutional Activities | |||||||||

| Religious trade/civil associations | 6.0% | 6.6% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 7.3% | 20.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 7.9% |

| Religious political parties | 23.5% | 37.2% | 3.0% | 46.2% | 54.5% | 40.0% | 66.7% | 24.2% | 44.7% |

| Publication/dissemination of written religious material | 10.9% | 12.0% | 0.0% | 7.7% | 23.6% | 100.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 5.3% |

| Clergy & Institutional Voice | |||||||||

| Sermons by clergy | 21.3% | 27.3% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 65.5% | 80.0% | 33.3% | 3.0% | 13.2% |

| Political activity by clergy/rel. institutions | 23.5% | 34.4% | 3.0% | 46.2% | 52.7% | 60.0% | 83.3% | 15.2% | 36.8% |

| Arrest/detention/harassment of religious figures/officials/rel. party members | 10.9% | 14.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 36.4% | 80.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 2.6% |

| Heads of religious orgs. must be citizens | 7.7% | 9.3% | 15.2% | 30.8% | 5.5% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 6.1% | 2.6% |

| All practicing clergy must be citizens | 2.2% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 7.7% | 3.6% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.3% |

| Government appoints clergy | 25.7% | 28.4% | 5.2% | 30.8% | 61.8% | 80.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 7.9% |

| At least one type | 66.1% | 76.0% | 57.6% | 100.0% | 98.2% | 100.0% | 83.3% | 45.5% | 73.7% |

| Mean | 5.54 | 7.17 | 1.55 | 7.92 | 13.55 | 26.60 | 8.67 | 2.30 | 4.02 |

| Mean scaled for comparison | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

Table A4.

Non-Institutional Restriction on All Religions, 1990–2014.

Table A4.

Non-Institutional Restriction on All Religions, 1990–2014.

| Restrictions on/Government Actions | All Countries | By Country Grouping in 2014 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2014 | EWNOCMD | Orthodox | Muslim | Communist | Buddhist | The Rest Democracies | The Rest Non-Democracies | |

| Clergy holding political office | 12.6% | 16.2% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 80.0% | 66.7% | 27.3% | 18.4% | 15.8% |

| People are arrested for religious activities | 3.8% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5.5% | 80.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Public display of religious symbols | 7.1% | 11.5% | 5.2% | 0.0% | 23.6% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Conscientious objectors not allowed alternative service and are prosecuted | 17.5% | 10.4% | 0.0% | 15.4% | 20.0% | 40.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 5.3% |

| Public religious speech | 7.1% | 8.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 18.2% | 80.0% | 16.7% | 3.0% | 0.0% |

| Religious-based hate speech | 37.2% | 53.0% | 87.9% | 84.6% | 47.3% | 40.0% | 50.0% | 24.2% | 47.4% |

| Control/influence rel. education: public schools | 25.7% | 26.8% | 18.2% | 23.1% | 52.7% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 24.2% | 5.3% |

| Control/influence rel. education: in private | 18.0% | 23.5% | 9.1% | 15.4% | 50.9% | 80.0% | 33.3% | 9.1% | 2.6% |

| Control/influence rel. education: universities | 9.3% | 9.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 27.3% | 40.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Other religious restrictions | 30.6% | 43.7% | 27.3% | 53.8% | 56.4% | 100.0% | 33.3% | 33.3% | 39.5% |

| At least one type | 67.0% | 86.9% | 90.9% | 100.0% | 94.5% | 100.0% | 83.3% | 84.8% | 68.4% |

| Mean | 3.48 | 4.28 | 3.09 | 3.69 | 6.93 | 13.20 | 5.00 | 2.30 | 2.13 |

| Mean scaled for comparison | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 1.32 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

References

- Almond, Gabriel, R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan. 2003. Strong Religion: The Rise of Fundamentalism around the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, R. Scott. 2000. The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Auslin, Michael R. 2019a. “The Empire Strikes Back.” Hoover Digest No. 2 (Spring): 109–13. Available online: https://www.hoover.org/research/empire-strikes-back-1 (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Auslin, Michael R. 2019b. “China’s war on Islam.” Spectator (May 1st). Available online: https://spectator.us/china-islam-uighurs/ (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Balci, Bayram, and Altay Goyushov. 2014. Azerbaijan. In Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. Edited by Jorgan Nielsen, Samim Akonul, Ahmet Alibasic and Egdunas Racius. Leiden: Brill, vol. 6, pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, Jocelyne. 2013. Why the West Fears Islam: An Exploration of Islam in Liberal Democracies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, James S. 1986. Social Theory, Social Research, and a Theory of Action. American Journal of Sociology 91: 1309–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Appollonia, Chebel. 2015. Ariane Migrant Mobilization and Securitization in the US and Europe: How Does It Feel to be A Threat? New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Djupe, Paul A., and Jacob R. Neiheisel. 2018. Political mobilization in American Congregations: A Religious Economies Perspective. Politics & Religion. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Richard M. 1962. Power-Dependence Relations. American Sociological Review 27: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger. 1990. Religious Deregulation: Origins and Consequences. Journal of Church and State 32: 609–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Finke, Roger. 2013. Origins and Consequences of Religious Restrictions: A Global Overview. Sociology of Religion 74: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finke, Roger, and Jaime Harris. 2012. Wars and Rumors of Wars: Explaining Religiously Motivated Violence. In Religion, Politics, Society and the State. Edited by Jonathan Fox. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Roger, Dane R. Mataic, and Jonathan Fox. 2017. Assessing the Impact of Religious Registration. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 720–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Jonathan, and Lev Topor. 2021. Why Do People Discriminate Against Jews? New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2008. A World Survey of Religion and the State. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2011. Building Composite Measures of Religion and State. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 7: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2015. Political Secularism, Religion, and the State: A Time Series Analysis of Worldwide Data. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2019. The Correlates of Religion and State. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2020. Thou Shalt Have No Other Gods before Me: Why Governments Discriminate Against Religious Minorities. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan, Roger Finke, and Dane R. Mataic. 2018. New Data and Measures on Societal Discrimination and Religious Minorities. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 14: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan, Roger Finke, and Marie Eisenstein. 2019. Examining the Causes of Government-based Discrimination against Religious Minorities in Western Democracies: Societal-level Discrimination and Securitization. Comparative European Politics 17: 885–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, Paul. 2008. The Great Secularization Experiment: What Soviet Communism Taught Us about Religion in the Modern Era. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Anthony. 2008. The Political Origins of Religious Liberty. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2007. Religious Persecution in Cross-National Context: Clashing Civilizations or Regulated Religious Economies? American Sociological Review 72: 633–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2011. The Price of Freedom Denied. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koesel, Karrie J. 2014. Religion and Authoritarianism: Cooperation, Conflict, and the Consequences. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru, Ahmet T. 2009. Secularism and State Policies toward Religion. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lausten, Carsten B., and Ole Wæver. 2003. In Defense of Religion: Sacred Referent Objects for Securitization. In Religion in International Relations: The Return from Exile. Edited by Fabio Petito and Pavlos Hatzopoulos. Palgrave: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, Daniel. 2019. Religious Freedom in Islam: The Fate of a Universal human Right in the Muslim World Today. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, James T., and Bryan Edelman. 2004. Cult Controversies and Legal Developments Concerning New Religious Movements in Japan and China. In Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe. Edited by James T. Richardson. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, pp. 359–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkissian, Ani. 2015. The Varieties of Religious Repression: Why Governments Restrict Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scolnicov, Anat. 2011. The Right to Religious Freedom in International Law: Between Group Rights and Individual Rights. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, George M. 2001. Religions in Global Civil Society. Sociology of Religion 62: 515–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, Kenneth D., Adam L. Silverman, and Kevin S. Friday. 2005. Making Sense of Religion in Political Life. Annual Review of Political Science 8: 121–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2006. The Red, Black, and Gray Markets of Religion in China. The Sociological Quarterly 47: 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2012. Religion in China: Survival and Revival under Communist Rule. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2019. Will Chinese House Churches Survive the Latest Government Crackdown? Christianity Today. December 31. Available online: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2019/december-web-only/chinese-house-churches-survive-government-crackdown.html (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Zhang, Lihui. 2020. Religious Freedom in an Age of Globalization, International Law and Human Rights Activism. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 23/14), The German-Israel Foundation (Grant 1291-119.4/2015) and the John Templeton Foundation. Any opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the supporters of this research. |

| 2 | UN Universal Declaration of Human RIghts Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights/ (accessed on 12 April 2021). |

| 3 | This is evident in the area of religion as well. Later UN documents, both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance (1966) and Discrimination Based on Religion and Belief (1981), acknowledge the importance of the religious collective, but they remain focused on individual rights (Scolnicov 2011). |

| 4 | These actions were documented in the Religious Liberty Commission of the Evangelical Fellowship of India report: “Hate and Targeted Violence against Christians in 2019.” Available online: http://www.efionline.org/articles/351/20200315/rlc-report-hate-and-targeted-violence-against-christians-in-2019-persecution-persecuted-church-church-in-india.htm (accessed on 20 April 2020). See the India International Religious Freedom Report, 2018 for additional estimates on violence and persecution of religious minorities by non-state actors. |

| 5 | The non-profit Radio Free Asia reported that the Chinese government destroyed more than 5000 mosques in 2016–17 alone and more that 1 million Muslim Uighurs were sent to re-education or internment camps (Auslin 2019a, 2019b). |

| 6 | For a more detailed discussion of the data collection procedures, reliability tests, and an explanation for why the scales are additive rather than weighted see Fox (2008, 2011) and Fox et al. (2018). |

| 7 | US State Department Religious Freedom Report 2009–2014, Eritrea, available online: https://www.state.gov/international-religious-freedom-reports/ (accessed on 12 April 2021). |

| 8 | US Department of State Religious Freedom Report Bulgaria 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013. |

| 9 | As some countries were not yet independent or had no functioning government in 1990, the numbers for 1990 represent 1990 or the first year in which data are available. |

| 10 | Criminal Code of the Republic of Armenia 2003. |

| 11 | US Department of State Religious Freedom Report Morocco 2010. |