5. Events That Capture the Vision

In the interim, it was as a student of theology pursuing a graduate degree at University of St. Michael’s College that I met Father Stephen Dunn, CP who, as the director of the Elliott Allen Institute for Theology and Ecology (EAITE), introduced me to the work of Thomas Berry through his course on Environmental Ethics and later more deeply as part of a pastoral residency program at Holy Cross Centre. Early on in my part time studies, while still engaged in a full-time architectural practice, two pivotal events helped to definitively shift my focus towards eco-theology and commit to enrollment in the EAITE.

The first of these was an opportunity in 1990 to attend a symposium hosted at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education featuring Thomas Berry as keynote speaker. Listening about the earth through the eyes of Thomas Berry was both inexplicably and simultaneously alluring and disorienting, so I defer once again to the expressive words of Brian Swimme in his forward for

The Dream of the Earth:

“Colors reveal unsuspected hues, and not all of them are soothing; sounds swell with new meanings, but not all of them are comforting; human actions bespeak hitherto unimaginable significance, but not all of it is complimentary. But in both pleasure and pain, the Earth folds back more intimately on itself through this vision. In the magic of these words, we capture a glimpse of an unseen and unsuspected Earth beauty. We find ourselves seized by the conviction that we have made our way to a creative wellspring of the Earth adventure.”

The second was an opportunity to visit the Centre for Ecology and Spirituality at Port Burwell for the first time. While completing our studies at University of Toronto, my partner Kimberly and I began attending worship services at the Newman Centre, the Catholic ministry on Campus. In preparation for Easter of 1991, Heather Eaton, one of several doctoral students who had recently graduated from EAITE, announced to the parish that she would lead a Lenten Retreat at the Centre. For three days in March, immersed in the raw beauty of the Centre’s natural landscape, Eaton helped us to explore ways in which we could integrate into our daily lives Berry’s invitation to bring about a more mutually-enhancing human relationship with the earth. The sense of urgency was heightened by images of the Kuwait oil wells afire and spewing thick black smoke across the desert, a consequence of Iraq’s “scorched earth” policy as they retreated during the Gulf War.

1 Juxtaposed to this devastation was the discovery of thousands of red wing blackbirds that had arrived on their spring migratory return to Canada prematurely.

These formative experiences also prompted my partner and I to henceforth attend the annual colloquia where we were able to deepen our understanding of and commitment to the values of eco-theology from the many new insights that inevitably emerged from Thomas Berry’s conversations with invited guests and to eventually respond to the call to serve as lay associates in support of the Centre’s mission. For many summers, Holy Cross Centre became our second home. Time spent within the four distinct and interconnected ecosystems of beach, marsh, meadow, and forest within the bounds of the Centre’s property, helped to inform the meaning of sacred landscape and the sense of divine presence afforded by immersion in the natural world. Flocks of migrating tundra swans that would magically fly overhead during outdoor liturgies combined with thousands of monarch butterflies that would gather in the trees of the property before continuing their arduous journey south over the lake all seemed to reinforce the understanding that this place was indeed holy ground. In conversation with Berry, the staff of the Centre had created a series of modest outdoor mediation sites that were located and arranged within these ecosystems to serve as a contemplative pilgrimage honoring the Universe Story.

“In Berry’s terminology, these were profound readings of the cosmic ‘scriptures of the earth’. They highlighted eight irreversible transformations within the Evolutionary Epic: four of the macro universe, four of the earth’s evolution once the human emerged.”

On a smaller scale, these eight stations were represented in stained glass windows that adorned the glass house chapel of the Centre’s main house overlooking the meadow where we would gather for the celebration of the eucharist.

It was here at the Centre, with about one hundred people gathered around them in 1992, that Berry, along with his co-author and creative collaborator of ten years, physicist, Brian Swimme, launched their book

The Universe Story. This epic narrative brought fulfilment to Berry’s desire to provide humans with a compelling story that would shift us away from the allurement of unsustainable consumption and provide the necessary inspiration for restoring our relationship to the earth. (

Angyal et al. 2019, p. 120)

Berry tells of how publishing

The Universe Story seemed to sum up his whole career of spiritual and cultural enquiry:

“This was the culmination of my childhood concern for the beauty and grandeur and wonder of the world. My study of indigenous peoples and their remarkable sensitivity to the surrounding universe, my study of the great classical civilizations, my study of western culture: all conformed to the same understanding—the immersion of the human in the world of nature was also immersion in the world of the sacred. Every being of planet Earth, even of the entire universe, was participant in the grand liturgy of the universe that I had for so many years celebrated in my earlier years of monastic seclusion.”

Meanwhile, after participating in a “Mission Fulfillment Weekend Retreat”

2, I was invited to serve on the Worship and Liturgy Commission for the Passionist’s St. Paul of the Cross Province in the US, of which the Congregation of Canadian Passionists was a Vicariate. One of the commission’s first tasks was to prepare the liturgies for the upcoming Provincial Chapter

3 which was being held at a venerable old hotel in the Poconos during the spring of 1998. As a member of the team, I was encouraged to attend all the proceedings with the exception of participating in the election of the new Provincial and his leadership team, which understandably, was available only to vowed members of the Passionist Congregation.

For me, the years of seeking the architect’s grasp of sacred space would now become uniquely manifest in a special experience with the Passionists. With this time alone, I decided to take a walk in the surrounding woods, eventually finding a trail that led to the valley below where I found a stream gently meandering beneath the forest floor. I was drawn by the sound of the flowing water to find a rock in its midst in order to rest and enjoy the freshness of the spring landscape that was bursting with new life. As my eyes were drawn to the light overhead being filtered through the verdant green of the emerging forest canopy, I came to realize that I was encountering one of those profound experiences that constellate a heightened sensitivity and deep connection to the natural world. This prompted me to further muse about ways in which this experience of filtered light from above could be replicated within the design of a worship environment. At the time, I was unaware that just such an opportunity would soon arise.

6. St. Gabriel’s Passionist Parish Church: Giving Tangible, Meaningful Expression to Eco-Theology: Dealing with Practical Detail While Maintaining the Vision

Shortly thereafter, I received an invitation from Father Terry Kristofak, C.P., who at the Chapter had been elected as Provincial leader for a second term, to facilitate a discussion with the Passionist Community of Canada and representatives from St. Gabriel’s Passionist Parish. A number of practical circumstances had led to the closing of the Retreat Centre in 1998. Fortunately, however, another opportunity arose that would enable Berry’s legacy to continue. At the time, a new rapid transit subway line was being built under Sheppard Avenue in Toronto right in front of St. Gabriel’s church. When completed in 2002, it was expected to attract considerable urban intensification along its route. “It was now financially possible to build a new ecologically sound church as well as address the spiritual challenge Berry calls being ‘between two stories’” (

Dunn 2010, p. 72).

The purpose of the meeting was to envision possibilities for the future development of the property at 650 Sheppard Avenue East, in Toronto. The discussion focused on the following two core values which were to be expressed in the redevelopment:

- (1)

To determine how the Passionist Community can retain control of a development project that will meet their financial goals and provide senior friendly accommodation for the Passionists living in Toronto.

- (2)

To determine how to develop a marketable project that will provide a Passionist liturgical statement and a value statement about the natural world as expressed by the Centre for Ecology and Spirituality and vision of Passionist Father, Thomas Berry.

Larkin Architect Limited was subsequently awarded the commission to complete the feasibility study which was launched through the facilitation of a community consultation and visioning workshop.

“St. Gabriel’s Sustainable Community Development Design Charette” took place from the evening of 4 December to the evening of 5 December 1998 at St. Gabriel’s Seminary as a way of exploring possibilities for achieving these objectives. Participants included vowed members of the Passionist Community, the parish, and a select group of consultants who specialized in sustainable development and affordable housing. This diverse group helped to review a number of important issues surrounding the project vision/dream, governance possibilities, financial goals, current municipal zoning and official plan legislation affecting the property, potential uses on the site, community life of the parish, the built and natural environments, and performance objectives for sustainable development.

A further articulation of the project issues and a written description of four redevelopment options emerged from post-charette meetings with the Passionist Community at St. Gabriel’s. A development approximating what was deemed to be most consistent with the values that emerged from the charette was further described graphically in preliminary schematic site plan form to assist in their deliberations. It was hoped that the feasibility study report would now provide the Passionist Community with the data necessary to decide upon an appropriate redevelopment strategy.

An important outcome of the study was the determination that, due to the nature of its original construction, the existing church would not be easily adaptable to accommodate the anticipated 30% increase in capacity precipitated by the projected rise in population drawn to live along a major public transit infrastructure. In addition, its central location on the property would limit the potential for redevelopment.

Eventually, by the summer of 2001, in response to a request for proposal, Larkin Architect Limited was successful in being awarded the commission to design the new church. Father Stephen Dunn, C.P. would serve as client contact and champion the project through to completion. The commission would represent a unique opportunity to manifest in physical form, my graduate studies in eco-theology, and to participate in what Thomas Berry described as the “Great Work” (

Berry 1999). Eventually, I would come to understand the design process and its ultimate solution as my ‘Master’s Thesis’. By then, the Passionist Community had come to the decision that they had neither the internal expertise nor the energy to proceed with developing the property on their own. This decision led them into negotiations with a local residential developer. Such arrangements were normally structured to allow for a base purchase price to the vendor that would then incrementally increase with any additional density that the developer could obtain as part of their own approval’s process with the city.

Meanwhile, as primary architectural and liturgical consultant, Larkin Architect Limited invited a number of collaborators from various design and engineering disciplines with shared values and expertise in sustainable strategies to join the design team. Working from the values that emerged during the charette with a building committee of Passionist and lay leadership from the parish, we were able to articulate the three foundational criteria that would inform that design process for the new church moving forward:

Liturgical design principles as outlined in the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishop’s official document,

Our Place of Worship4An ecological spirituality based upon the work of Fr. Thomas Berry, C.P.

5Sustainable design principles as defined by the US and Canadian Green Building Councils through their LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Green Building Rating System.

6

Meeting the first criteria would ensure that the new church reflected current liturgical norms in Canada. Meeting the second criteria, though less tangible, would serve to guide every decision in the iterative design process. We soon realized, however, that one tangible and meaningful way to meet this second criteria would be to have the new church design incorporate leading sustainable design strategies that were emerging within the building industry at the grassroots level in response to what was being identified at the time as the significant contribution to greenhouse emissions emitted by the construction and operation of the built environment.

7 This goal led to the decision in late 2002 for me to achieve my LEED professional accreditation, a process that would educate and test my knowledge of the US Green Building Council’s sustainable design strategies and qualify the project for accreditation.

8Although not explicitly identified, I was also aware of bringing to bear on the design process what I had learned from my theological studies about the phenomenological analysis of sacred space while taking a course on Primal Religions taught by professor Carl Starkloff, S.J. at Regis College. Of particular relevance was the seminal work of Harold W. Turner,

From Temple to Meeting House, The Phenomenology and Theology of Sacred Space, (

Turner 1979) which Fr. Starkloff had graciously leant me from his personal library as a resource for my term paper on the blessing ritual of our firm’s recently completed infirmary for the Loretto Sisters in Toronto.

- (1)

The sacred place as centre

- (2)

The sacred place as meeting point between the heavenly and earthly realms

- (3)

The sacred place as microcosm of the heavenly realm

- (4)

The sacred place as immanent-transcendent presence of the divine

8. The Iterative Design Process Unfolds

With all of the preparatory work completed, the design team finally began to articulate the conceptual design for a new church to be located in the southeast corner of the property with frontage directly on Sheppard Avenue for visibility and ease of access not only for those who attended St. Gabriel’s from within the parish boundaries, but also for those who came from afar to experience the unique charism of the Passionists, their pastoral leadership, and creative ministries. This scheme was presented to the local municipal planning authorities and immediately rejected because it did not conform to their vision of Sheppard Avenue taking on the character and ambience of Paris’s Champs Elysee which was to be articulated by wide, tree lined boulevards, outdoor café terraces providing streetscape animation, and a consistent row of eight storey buildings with colonnaded bases on either side. A single storey worship space and parish centre did not fit within this urban design model. They made it clear to us that a more appropriate location for the church would be the northeast section of the property, set far back from Sheppard Avenue adjacent to Elkhorn Drive, a local neighbourhood residential street.

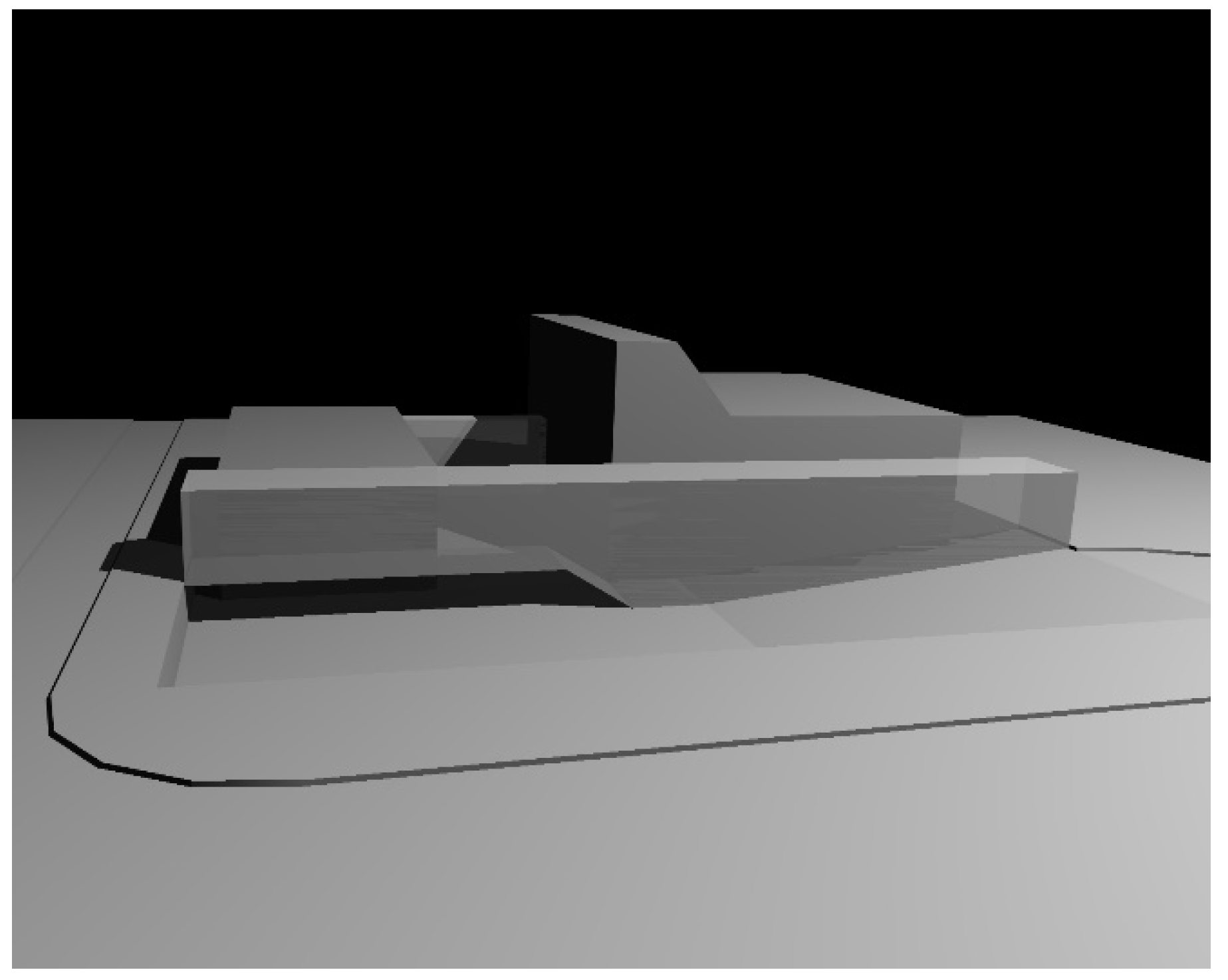

In the end, a 2-acre site was established for the church to be severed from the original 7 ½ acre property leaving a residual parcel of 5 ½ acres available for sale to a developer, the proceeds of which would fund the construction of the new church. The original conceptual design that linked the two major programmatic spaces of worship space and parish centre with an enclosed courtyard between, would not work in its new relegated location, so it was back to the drawing boards for the design team (Refer to

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

In the meantime, negotiations with the selected developer had abruptly ended after another, significantly larger, and therefore more lucrative site suddenly became available further to the east on Sheppard Avenue. Without a purchaser, the project could not proceed. After some time had elapsed, one of the parish committee members who also happened to be a local real estate agent, brought another developer to the negotiating table and eventually a purchase price based upon fair market value “as-is” was agreed upon that would enable both parties to continue with their approval’s process independently of each other. In other words, the final land valuation was based upon the existing zoning of the property and would no longer be tied to the developer’s ability to maximize the density as part of their re-zoning application process.

Because the original 1950s church, still in use by the parish, was located on the portion of land sold to the developer, it would be necessary to first successfully complete the church project’s municipal approvals and construction process before the developer could demolish the old church and begin construction on their own redevelopment project. Thus, it was felt that this decision would enable the Passionists and the parish to free themselves from a complex approval’s process and expedite the completion of the church. The design of the church was to proceed such that it met all of the current zoning parameters relating to the residual church property and subsequently result in a smooth, as-of-right approvals process.

Unfortunately, this assumption proved to be naïve. The local municipal councilor, in an effort to ingratiate himself with the local residents, had promised them he would object to any redevelopment on the north side

10 of Sheppard Avenue until the entire south side had been completed, despite the fact that it was in contradiction to the terms already outlined by the city in the context of its redevelopment policies for the Sheppard East Subway Corridor Plan. Furthermore, he insisted on perpetuating the misconception that the land deal between the developer and the Passionists must be tied to maximizing the density on the land, and therefore remained determined to do everything within his power to undermine and stall the as-of-right approvals process for the church. He was convinced that in doing so, the developer would become frustrated with the delays and walk away from the deal, thereby allowing the status quo to remain, and the councilor to appear as a hero to his constituents. His obstreperous machinations were first encountered when the local planning staff was instructed to delay the land severance approval that was necessary to legally distinguish the new 2-acre site for the church from the residual lands sold to the developer. The result of this tactic forced the Passionists to appear before the Ontario Municipal Board which was established to allow parties who had met objections to their municipal approval’s process to appeal to the provincial body that oversaw such matters.

A delay of several months did occur, but eventually, the severance was secured and the design team continued their process of attempting to articulate a church that would embody the aforementioned foundational criteria and other important influences established from the outset. With each iteration, new ways of giving expression to them were explored, tested by the design team, and then vetted by the Passionists and the parish building committee. Many practical problems had to be solved in ways that would reinforce rather than undermine the vision quest to embody Thomas Berry’s eco-theology.

Finding creative ways to deal with the parking requirements and other parameters such as building height, setbacks from property lines, etc. imposed by the zoning by-law, mitigating the impact of the developer’s surrounding residential towers, determining the best ways to passively harness the sun’s energy, managing the relationship between interior and exterior, determining the most appropriate landscaping for the property, the question of worship space seating arrangements and the sequence of movement to the sanctuary in addition to the parameters associated with the project’s functional program and budget were just some of the many design considerations that had to be resolved in a coherent, integrated way.

Addressing two significant practical issues which were initially understood to be relatively independent of each other ended up resulting in synergistically contributing to a common resolution while happily strengthening the overall design intent of the entire church. In the penultimate iteration

11, the worship space was characterized by a flexible circular seating arrangement focused around a central altar that was bathed with natural light via a large sky-lit oculus directly above. This design responded to a desire to highlight the liturgical centre with “heavenly light” thereby serving to distinguish this space for clergy from the congregational seating and giving expression to Turners’ function of providing a meeting point for the heavenly and earthly realms. At the south end of the worship space was a massive stone wall thick enough to have carved out of its massive form spaces for the reservation of the tabernacle, the reconciliation rooms, and carefully framed openings that provided views and access to full height, wall to wall, south facing glazing and the garden beyond. The winter sun’s energy would be passively harnessed through the south glazing which would then be stored in the mass of the “trombe” wall

12 of stone as a heat sink during the day and then release that energy into the space at night, thereby reducing the dependency on fossil fuels to heat the building (Refer to

Figure 3). The garden, which was in fact a “green roof” above the parking lot, had its landscaped supporting concrete slab “folded” up about 20 feet in the air in order to provide an opening for natural light to find its way to the parking garage below and artificially extend the horizon of the garden to “mask” the surrounding residential towers.

Just after presenting that scheme, some members of the parish building committee visited the Passionist Retreat Centre in West Hartford, Connecticut and came back impressed with the antiphonal seating arrangement they experienced while attending mass. Typical of monastic traditions, this form of seating is characterized by two banks of pews or stalls that face each other to facilitate the call and response of Gregorian chant and the “praying of the office”. The committee thought that this arrangement would be a way in which they could honor the monastic tradition of the Passionist charism.

13 From the perspective of the Constitution on the Liturgy of Vatican II and the Roman Missal, this seating arrangement, like the previous circular one, also satisfied the preference that the parishioners be aware of each other, gathered as a faith community to share in the sacraments, representing a primary symbol of Christ’s presence in their midst. This desire cited by the committee also prompted Father Steve Dunn to suggest eliminating the “trombe” wall altogether which would then open up an expansive view to the garden and thereby serve to extend the sacred space of the worship environment into the sacred space of the garden beyond to emphasize that when we gather to worship, we do so within the greater context of creation.

This prompted salvaging of the original church pews, re-finished and modified to suit the new arrangement, and initiated a relocation of the reservation chapel and the reconciliation rooms to the north end of the worship space. This allowed the concrete floor and flanking walls of the south facing window to serve as the heat sink now that they were exposed to the winter sun’s rays. Fabricated to be eight times more energy efficient than the walls of the original church, the expansive glass of the south window, in addition to offering a visual connection with the garden, also helped to improve the energy efficiency of the new church. The precise form and extent of the projecting roof canopy ensured the maximum potential for harvesting passive solar heating in winter while shading the building to reduce cooling loads in summer (Refer to

Figure 4).

The antiphonal seating arrangement also allowed for the articulation of a sacred axis that began with the presence of Christ in the consecrated eucharist reserved in the tabernacle at the north end of the worship space and terminated with an understanding of the immanent presence of the divine in creation as expressed by the garden at the opposite end (Refer to

Figure 5). This sacred axis would also embrace the placement of the altar, the ambo (pulpit), and the baptismal font all of which were reclaimed from the old church and modified to alert parishioners that the new church design both honoured the long tradition of Passionist leadership and also spoke of “the New Story”. Sufficient space was left between the altar and ambo to emphasize that receiving the Word of God would invite worshipers to participate in the eucharistic meal. The presiding priest’s chair would be located at the centre point between the altar and ambo in order to recognize his leadership role and symbolic representation of Christ’s presence. However, instead of being elevated, it would remain level with the congregation, to emphasize that the entire assembled community of faith, by virtue of their baptismal covenant, formed part of the royal priesthood. Finally, the original marble font, re-designed to flow with “living water” and reference the assembly of roof scupper and wetland, which according to contemporary liturgical norms is most often located near the entrance to the worship space, was uniquely placed immediately in front of the window overlooking the garden to emphasize that when we are baptized into the Christian faith community, we are also welcomed into the broader Earth community (Refer to

Figure 6).

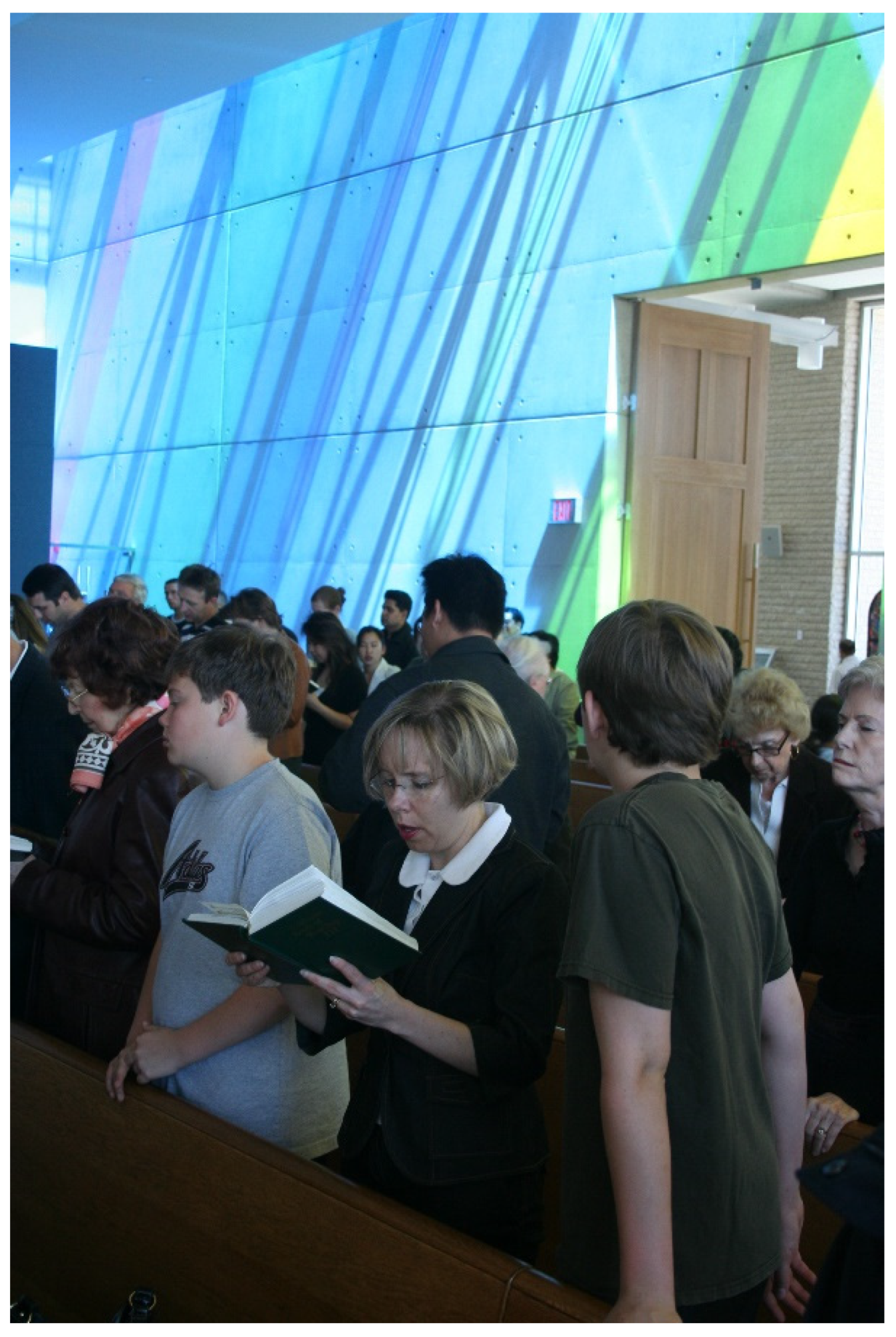

Serendipitously, during this time of design development, our landscape architect, Ian Gray, introduced us to David Pearl, a glass artist friend, who collaborated with the team to create coloured glass panels for integration into the perimeter skylights that were situated above the remaining three walls of exposed concrete. The skylights were envisaged as a way of interpreting the formative experience that I had encountered on the forested valley floor during the Passionist Chapter in the Poconos. Movement from the south to the north is reinforced by the arrangement of colours in the skylight. Brilliant yellows are situated closest to the sun’s intense light at the south end whereas the deeper, richly hued azure blues and crimson reds at the north end provide a beautifully mysterious and meditative light for the chapel of reservation and the adjacent reconciliation rooms. The ceiling of the worship space stops short of the walls on all sides, appearing to hover weightlessly over the congregation, the cosmic coloured light of the perimeter skylights spilling into their midst from an unseen source high above. The dynamic play of natural light that is filtered by Pearl’s brilliantly choreographed coloured glass panels and further fractured by wall-mounted dichroic coated reflectors gives the worshipping faith community a sense that the cosmos is embracing the liturgical environment and actively participating in the ritual action of the liturgy. Similarly, time also takes on a cosmic dimension as the colours move in sync with the earth’s rotation. Seasonal influences on the sun’s intensity and inclination, together with the daily diversity of weather conditions, ensure that no two masses will experience an identical liturgical environment (Refer to

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

The nave is entered from the narthex on the cross-axis through a pair of massive fifteen-foot-high paneled doors reminding us that Christ is our “gateway” to salvation. This central ceremonial aisle ends at the sacred axis, facing the presider’s chair, which is located in the front row of pews amongst the gathered worshipping community. The space at the crossing remains void, free to receive the gifts, the bride and groom, and the body of the deceased. It also serves as a place to identify the liturgical season, allowing the altar to remain unfettered as a primary symbol (Refer to

Figure 11).

Further sketching and design development eventually resulted in a scheme that was agreed upon by the Passionists and the committee to be ready for the process of obtaining site plan approval with the city.

14 Working closely with the urban planners and legal advisors retained by the Passionists, the design team was instructed to submit a scheme that met all of the city’s zoning requirements without having to seek variances in an attempt to streamline the approval’s process and expedite the construction of the new church. Notwithstanding, the chief planner had the intention of using the private church property to extract a public pedestrian thoroughfare linking Sheppard Avenue (now to the south of the church property) with Elkhorn Drive, bordering on the church’s north end of the property. Not only was planning approval contingent upon providing the thoroughfare, but it had to be done in a manner acceptable to the planning authority, which in this case, dictated a straight pathway from one end of the site to the other.

This mandate was in direct contradiction to our design for pedestrian movement which was carefully choreographed to prepare parishioners for worship services. The path did begin with a straight section that led from the south property boundary to a circular terrace located on the south edge of the main garden, but deviated thereafter. Pedestrians who approach the church from Sheppard Avenue were greeted with “stations of the cosmic earth” situated strategically along the path through the garden. Based upon the series of eight stained glass windows commissioned for the chapel at the Passionist’s Holy Cross Centre for Ecology and Spirituality, the stations depict significant transformational moments in the evolutionary story of the universe and the pilgrim journey of humankind within that story. The first station depicts the “big bang”, the initial bursting forth of energy at the beginning of time from which all else has evolved. The following two stations move through the coalescing of matter to form our solar system and the emergence of early life forms within the seething primordial broth of our planet’s oceans. The fourth depicts the emergence of the human. Another station, which is not part of the sequence, depicts the cross lying flat on the earth surrounded by flowers as seen from above to remind us that the story of the cross is linked to the story of creation. A void with flowers emerging exists where the arms of the cross intersect reminding us that even though it is a symbol of suffering and death, the cross also proclaims hope and resurrection. It can be viewed from a circular terrace that terminates the walkway from Sheppard Avenue (Refer to

Figure 12).

From the central vantage point of the circle, those approaching from Sheppard are invited to pause and reflect upon several symbolic representations of Christian theology integrated into the design of the church that were designed to initiate a shift in one’s orientation towards Berry’s eco-theology and his understanding of the Earth as the primary revelatory presence of the divine. First and foremost, the circle would afford an expansive viewpoint to take in the beauty of the garden designed to reflect an indigenous, pre-settler landscape. Visually aligned with the circle’s centre, directly to the north, can be seen a sculpted roof scupper which, like the gargoyles of Gothic cathedrals, is designed to direct rainwater from the building, (and in this case), into a constructed wetland below. A primary element employed in the Christian initiation ritual of baptism to symbolize new life in Christ, the intention was to demonstrate that water had to be conserved, protected, and remain unpolluted lest it come to represent death instead. Whenever it rained, the wetland plants would flourish, but during times of drought, they would wither, thus reiterating the preciousness of water as a natural resource (refer to

Figure 13).

Juxtaposed to the “cross” station and the circle terrace are the remains of a tree that has been reclaimed from the property, its form “resembling a bowed head with branches splayed outward like suffering arms” (

Rochon 2006, p. R4). The copper cross from atop the original church roof is mounted to the back of this tree, reflecting a contemporary understanding of the Passion of Christ including the Passion of the Earth. To continue their approach towards the church, visitors must first re-orient their direction to circumnavigate a portion of the circle before continuing their journey under the outstretched arms of the natural “tree cross”. A straight path would therefore undermine this consideration (Refer to

Figure 14).

Upon passing the constructed wetland, parishioners emerge upon a generously proportioned piazza designed to be used as a seasonal outdoor gathering space and staging area for weddings and funerals. The deeply recessed arcade that articulates the front wall of the narthex overlooking the piazza is a contemporary expression of the form and architectural detailing of the Passionist Motherhouse in Rome. Made of a unique limestone from Manitoba that is distinguished by its many 450-million-year-old (Late Ordovician) embedded fossils of ancient sea crustaceans,

15 the fabric of the narthex defines an important chapter in the geological history of Canada and reminds us that the 2000-year Christian story is part of the earth’s 4.5-billion-year story (Refer to

Figure 15).

Once inside, the narthex

16 is terminated at the north end by a sky-lit, “living wall” (Refer to

Figure 16). Water running over the roots of the living wall’s plant material conditions and purifies the air of the narthex and worship space. The enzymes in the roots of the tropical plants process the volatile organic compounds and other atmospheric pollutants to “freshen” the air while the water provides natural humidification during winter and de-humidification in summer. Parishioners emerging from the underground garage are drawn into the narthex light above by the “living wall” and as they pass it are reminded of their baptismal covenant by the sound of its purifying waters (Refer to

Figure 17 and

Figure 18). They are also reminded of how the rainforests serve a crucial role as the earth’s lungs. At the opposite end of the narthex is a window that frames a view of the wetland and “tree cross” beyond.

Alternatively, one can delay proceeding from the circle terrace point of orientation and can rather choose to journey deeper into the garden passed the remaining stations. If so, they first come upon the fifth station which depicts the beginnings of agriculture, responsible for the significant shift away from nomadic hunting and gathering towards settlement and a more pervasive human presence upon the earth. The station characterizes this change with the appearance of a deep fissure that both physically and symbolically identifies the emerging rift between humans and the rest of creation (Refer to

Figure 19). In the next station, this fissure increases in breadth and depth to reflect the emergence of religions. Here the tree reappears, within its trunk and branches, the image of two human figures intertwined, one revealing an expression of suffering, and the other… an expression of ecstasy. The seventh station depicts the appearance of technology with the prophetic image of an atomic bomb’s mushroom cloud overshadowing the earth’s fertile green landscape below. The final station is out of sequence and is meant to represent a hopeful, resurrection theme. Captured in a large mural made from colourful Murano glass tile mosaics salvaged from the front face of the original church, it describes in abstract form, the bursting forth of flowers that characterized the dawn of the Cenzoic Age of earth history after the extinction of the dinosaurs some sixty-five million years ago. The angiosperms enabled the diversity of plant and animal life to evolve and flourish when humans appeared as a distinct species.

The impasse that existed between the chief city planner’s desires and the choreographed sequence of movement envisioned by our design prompted another appeal to the Ontario Municipal Board which ultimately sided with the church in its decision citing religious interpretation as a legitimate design determinant. With this decision, all municipal approvals were now theoretically secured and the execution of the site plan agreement with the city should have proceeded in a timely manner. However, once again, the local councilor used his influence to delay the process which ultimately required yet another appeal to the Ontario Municipal Board. The councilor finally relinquished his interference, but not without imposing a further caveat enshrined by the site plan agreement that forbade having any projections beyond the parapet of the church roof. Essentially, this stipulation prevented the possibility of installing solar photo-voltaic panels on the roof, at least for the foreseeable future.

Meanwhile, the delays coincided with inflationary pressures precipitated by the construction of venues to host the Olympic Games in Beijing, China, resulting in volatile market conditions that saw up to 50% increases in the price of steel, copper, and concrete. Final cost estimates for the church were escalating beyond the Passionists financial resources designated for the project. Once again, the design team had to return to the drawing table to conduct what is known in our industry as “value-engineering”, a term used to describe design changes, a.k.a. cuts and reductions, required to reduce costs to the point at which the project could be completed within budget. The design team’s response was to create a spreadsheet of items to be sacrificed along with their associated costs, much like an a-la-carte dinner menu, to assist the Passionists in making some difficult decisions. Items that ended up being deleted included the entire second floor of the administration wing meant to serve as a Passionist research centre and archive with its double helix access stair, the proposed green roof above the worship space, the buried garden cisterns that would store rain water harvested from the narthex roof for irrigation, and the heat chimney and operable windows that would allow for naturally occurring displacement ventilation in the church (Refer to

Figure 20).