Vincent Ferrer’s Vision: Oral Traditions, Texts and Imagery

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Everyone wishes to know when it will come, and I do not think I should give a sermon on it, as I have already written a treatise on it to the Pope, so turn to it and you will know, as many in this city already have it. There you will see the facts.

2. Mestre Vincent’s Vision

The second is another revelation made to a holy man who is alive, I think. And he was ill, with a serious illness, and that holy man had great devotion to Saint Francis and Saint Dominic. And he prayed to them to pray to God to bring him health, and the holy man was taken in spirit towards heaven, and he saw Jesus Christ, who was on a throne, and Saint Dominic and Saint Francis were below him, and they were praying. And they were saying, ‘Lord, not so soon; Lord, not so soon!’ And, in his heart, the friar said, ‘Oh, how Christ was resisting!’ And then Jesus Christ and Saint Dominic and Saint Francis descended to that sickly friar. And Jesus Christ said to him, ‘My child, I will wait for your preaching’. And he was healed. And I know him and I have spoken to him and he told me this many times. And now, good people, Jesus Christ is waiting for this friar’s preaching.

In the Holy Church, today we celebrate the blessed virgin martyr, Saint Cecilia, and I want to preach about her, not for any general reason, just because she is a virgin and martyr, but for a special reason, as on this day I started to preach around the world and announced my legatus a latere Christi, and because she has bestowed many graces upon me, which is why I wish to continue to preach about her.

3. Through Sermons

Second, it can be proven by the authority of the Holy Scripture, in Revelation chapter eighteen, which says ‘And I saw another angel flying through the midst of heaven, having the eternal gospel, to preach unto them that sit upon the earth, and over every nation, and tribe, and tongue, and people: Saying with a loud voice: Fear the Lord, and give him honour, because the hour of his judgement is come’. Let us look at who this angel is. I tell you that a good preacher is he who evangelises, meaning he who preaches the word of God to all, saying with a loud voice: fear the Lord, and give him honour, because the hour of his judgement is come, etc. So, let us see that nothing has been corrected by the preaching of Dominicans and Franciscans. As in the time of Saint Dominic, no usury prevailed, except among the Jews. Today, we find it among Christians. And let us see that clergymen do not respect their own religion, and the same can be said of all other mortals. In this moratorium in which we find ourselves, few direct their prayers to the Virgin Mary, and for this reason it will arrive quickly, very quickly, and soon. This can be proven thanks to some revelations. The first is that a certain Franciscan, whom I consider to be virtuous, upright, and devout, was ill, around twenty years ago. And on the eve of Saint Francis, he prayed to the saint to intercede before God to recover his health. When his pleas ended, he fell into a deep sleep, and the Lord appeared with Saint Francis and Saint Dominic, who prayed to God to delay the arrival of the end of the world. And Saint Francis also prayed to God for the ill man. But Our Lord Jesus Christ seemed cold, like marble. He approached the sick man, gently touched his face, and told him, ‘Go and preach around the world, and when your preaching is over, I will send the Antichrist’. The friar stood up and found himself completely cured, and since then, he has not ceased to go around the world preaching every day so that people may convert to God. Therefore, see the homily of Saint Gregory in the Gospel: ‘And there shall be signs in the sun, and in the moon, and in the stars’. Brethren, we have seen many signs in the sun and the moon, we have also seen earthquakes, so that many signs of the judgement of God have passed and few remain. That is why the end of the world will come soon. Seven hundred years have passed since Saint Gregory said those words, and if he spoke like this, with much more force we can say: remember that I told you.

The second is another revelation made to a holy man who is alive, I think. And he was ill, with a serious illness, and that holy man had great devotion to Saint Francis and Saint Dominic. And he prayed to them to pray to God to bring him health, and the holy man was taken in spirit towards heaven, and he saw Jesus Christ, who was on a throne, and Saint Dominic and Saint Francis were below him, and they were praying. And they were saying, ‘Lord, not so soon; Lord, not so soon!’ And, in his heart, the friar said, ‘Oh, how Christ was resisting!’ And then Jesus Christ and Saint Dominic and Saint Francis descended to that sickly friar. And Jesus Christ said to him, ‘My child, I will wait for your preaching’. And he was healed. And I know him and I have spoken to him and he told me this many times. And now, good people, Jesus Christ is waiting for this friar’s preaching. But be aware that he is old, over sixty years, and he has little life left. Know that, from the beginning of the world until the end, when our Lord God wants to do something again, first He sends a messenger to warn the people, which is what He did in Noah’s flood, which was a great destruction of people, as only eight people remained. And a messenger came beforehand to tell them. And they did not believe him and they scorned him; and then they were caught off guard. Furthermore, before the renovation of the Jews, did He not send a prophet, Jeremiah, and they did not believe him? And now, good people, this is the renovation. And that is why God revealed that we had a messenger.

The second revelation was made to a holy man who was sick and could not recover, to whom God told him to come and preach about the Antichrist, and for however long his preaching lasted, so too the world would last. And he said that he was a man aged sixty years; and that he could not say who he was. And the day before, he had said that he was sent to preach about the Antichrist, and that he was sent by Pope Jesus. By which he implied that he was this holy man, and that is what he implied every day, and we all understood that he was referring to himself.

Before the destruction of the flood, God sent the great man Noah to warn the people, preaching how the world was to be destroyed, and that they should do penance. For fifteen years now, another Noah has been preaching the destruction of the world around the world, and some mock and ridicule him.

Good people! Be well warned of this day that will soon come to be. Some say, ‘mestre Vicent is only saying it to frighten us’; but telling falsehoods when preaching is a mortal sin, and I would not tell you such a thing.

And you see, then, that God wishes to destroy all of this world with fire, and that he sends a messenger, which Saint John says in Revelation (chapter eighteen): ‘Et vidi alterum angelum euntem per medium celum, [habentem Evangelium eternum, ut evangelizaret sedentibus super terram, et super omnem gentem, et tribum, et linguam, et populum, dicens magna voce: Timete Deum et date illi honorem] quia venit hora iudicii eius’. There are many mysteries. ‘Alterum angelum euntem per medium celum’; he does not say ‘vidi angelum’. Why does he say ‘alterum’? I will tell you. It is like a friar of Saint Dominic or of Saint Francis who observes the rules correctly, like Saint Francis, saying now: ‘Oh, see here another Francis’, and he is not Saint Francis, but another, like the one Saint John speaks of: ‘Vidi alterum angelum’, because he must have the life of an angel. And how? Because the angel wants nothing but to honour God: he does not want clothes, or gold, or silver, or friendship of people or friends; he is solitary, as an angel only desires to honour God and for souls to be saved. Then, the angel is hidden, no one sees him; like him. Then, ‘volantem per medium celum’: this is what Saint Gregory says, that ‘celum’ is understood as Christianity, as in heaven there are twelve signs, by which we have influences with which we live; thus, Christianity has twelve articles of faith, by which we know God and what is needed for salvation. Then, in heaven there are seven planets, by which we have many oppressions; and you see that Christianity has seven sacraments of the Church, by which the Church and Christianity are governed. Then, in heaven there are many small stars; and here you see the infinite graces we have from God. And then, ‘habentem evangelium eternum’, that is, the Bible, the Old Testament, and the New Testament is represented in the Old. And then, ‘ut evangelizaret sedentibus super terram’, that is, to the secular lords, kings, dukes, ‘dicentem eis peccata sua clare’, and to the prelates, too, and to all the others. Then, ‘super tribum’: they are the Jews, who go from tribe to tribe, and that preacher, in the lands where they are, he must make them come to the sermon to declare the truth to them, and hear the truths of their law. Then, ‘et linguam’; they are the Muslims, and he must also make them come to the sermon to hear the falsehoods and truths of their law. And that messenger did not have to go for Granada, or for Tartary, but for Christianity. Then, ‘super omnem gentem’: these are the Christians, rich and poor, as he must preach to them all and tell them their sins, and reprimand them so that they correct their errors before God soon. Then, ‘et populum’: they are the priests and holy men, as he must appear to all of them. Then, ‘dicens magna voce: Timete Deum’, that is, through penance, because he must cause them to do penance for their sins: ‘et date illi honorem’, that is, show them how they must pray: kneeling down, thinking about God devoutly. And why? ‘Quia venit hora iuducii eius’.

4. The Letter to Benedict XIII

Everyone wishes to know when it will come, and I do not think I should give a sermon on it, as I have already written a treatise on it to the Pope, so turn to it and you will know, as many in this city already have it. There you will see the facts. And you see why I do not preach about it, because the justification is there.

In the second place the same conclusion is drawn from a certain other revelation (a most certain one to my mind), made just over fifteen years ago to a religious of the Dominican Order. This religious was very ill indeed and was praying lovingly to God for his recovery so, that he might again preach the word of God as he had been wont to do with great fervour and ardour. At last, while he was at prayer, these two saints appeared to him as in a dream, at the feet of Christ making great supplication. At length, after they had prayed thus for a long while, Christ rose and, with one on either side, came down to this same religious lying on his bed. Then Christ, touching him caressingly with the finger of His most holy hand, gave him a most definite interior comprehension that, in imitation of these saints, he must go through the world preaching as the Apostles had done, and that He, Christ, would mercifully await this preaching for the conversion and correction of mankind, before the coming of Antichrist. At once, at the touch of Christ’s fingers, the aforesaid religious rose up entirely cured of his sickness. As he diligently followed the apostolic mission divinely committed to him, Providence, in testimony of the truth, gave this religious, not only numerous signs as he had given Moses, but also the authority of the divine Scriptures as he had given John the Baptist since, because of the difficulty of this mission and the slight weight of his own unaided testimony, he was greatly in need of help. Hence, of the three divine messengers sent to men by divine Providence under the name of angels, many persons believe him to be the first, of whom John has written: ‘And I saw another angel flying through the midst of heaven having the eternal gospel to preach to them that sit upon the earth and over every nation and tongue and tribe and people, saying with a loud voice: “Fear the Lord and give Him honor, because the hour of His judgement is come”’. Let him who is able understand.

5. Duce’s Painting and the Transformation of Narrative as a Paradigm of the Three Media of Medieval Communication

In many parts of the world, I have seen many persons possessed by the devil, who were brought to one of the priests of our company for exorcism. When the priest began to exorcise them they spoke openly of the time of Antichrist, in accordance with what has already been said, crying out loudly and terribly so that all the bystanders could hear them, and declaring that they were forced by Christ and against their own will and malice, to reveal to men the truth as given above, so that they might save themselves by true penance.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Some sources resist classification. Given that the line separating homiletics from Vincentian literature is barely visible (Hauf 1983, p. 255), the complexity of textual transmission (Gimeno Blay 2019) calls for caution in any conclusions made. Within a broader framework, these three methods of communication have been marked from other disciplines (Zumthor 1989, pp. 152–53). |

| 2 | An aspect that could also explain a different diffusion of the story in the territories of contending obediences. |

| 3 | Pedro Martínez de Luna, a cardinal since 1375, ascended to the papal throne of Avignon in 1394, taking the papal name Benedict XIII. He never renounced what he considered to be his legitimate role despite resolutions issued against him at various councils. This makes him an antipope. Part of historiography has always referred to him as a Pope. In line with the most recent studies, the complexity of the events justifies calling him a Pope in this article. |

| 4 | The traditional starting point of the account for historiography is the Epístola Fratris Vincentii de tempore Antichristi et fine mundo (Fagês 1905, pp. 213–24). There is also a monograph on the vision (Montagnes 1988). The episode has also been situated in the papal palace (Teixidor 1999, pp. 230–31). There is some disagreement over the year it took place: it has been calculated based on the friar’s references to the episode years later, in his sermons and in his letter to Benedict XIII in 1412. The indication at the beginning of the letter in which he narrates the vision, ‘iam sunt elapsi plus quam 15 anni’, suggests the episode took place on 3 October 1396, though it is still widely thought to have happened in 1398. |

| 5 | The third person is a stylistic device that has been employed for millennia, notably by Julius Caesar and in the Gospel of John. In this specific case, Ferrer might have used it as a sign of modesty. Furthermore, it would reinforce the Thomist rationality with which he probably approached the issue, especially in interaction with Benedict XIII. |

| 6 | The sermon, on the theme ‘Reminiscamini quia ego dixi vobis’ (John 16:4, DRBO), has been published (Carbonero y Sol 1873; Cátedra García 1994, pp. 566–74). Its structure is highly analogous to that of the epistle Ferrer would write the following year, though the latter has a more scholastic format. |

| 7 | Ferrer’s new modus vivendi is reflected in the signing of his correspondence: Vincent Ferrer the sinner from prior to 1399 makes way for Vincent Ferrer the preacher. |

| 8 | There are earlier records of the friar’s itinerary after the vision, but they do not mention the content of the sermons (Ehrle 1900, pp. 362–63). In addition, this mention of the five-year period is consistent with the historiographical trend of situating the episode in 1398. |

| 9 | In his thirteen-day campaign, he gave sixteen sermons. Only four were on the theme of ‘De extremo iudicio’, all of which took place in Fribourg. He dealt with the subject partially in other locations. |

| 10 | This was mentioned in the sermon given in Payerne on Monday 17 March, 1404, on the theme ‘Adhuc modicum tempus vobiscum sum: et vado ad eum qui me misit’ (John 7:33) (San Vicente Ferrer 2009, pp. 105–6). |

| 11 | In fact, at some point after July 1412, the epistle to Benedict XIII was added. |

| 12 | Its heading is ‘Note on the end of the world: 3 conclusions’ (San Vicente Ferrer 2006, p. 518), a subject that was not included in the codex’s schedarium thematicum. There is a chronological paradox relating to the period indicated by the entry (Calvé Mascarell 2016, p. 366). |

| 13 | (John 16:4). This thema was included in the chronicle ‘Thalamus parvus. Le petit Thalamus de Montpellier’ (Société Archéologique de Montpellier 1840, p. 446). So affected was the chronicler by the sermon that he added a special note on its content. |

| 14 | The chronological framework indicated here raises questions. On another note, the central panel of the dismantled Saint Vincent Ferrer altarpiece, made around 1475 for the Duomo di Modena and attributed to Bartolomeo degli Erri, incorporates the Timete Deum and bears the inscription ‘Apoc 18′ [(Rev 18)]. This seems to be mere coincidence, as it is a common type of inaccuracy. |

| 15 | Something as seemingly trivial as the divine touch can point to the source used in figurations. |

| 16 | Without detriment to the well-known differences of opinion regarding when Vincentian discourse was at its most intense in terms of the apocalypse (Rusconi 1978; Daileader 2016). |

| 17 | Different yet compatible theories have been put forward on this subject (Rusconi 1999; Losada 2019). |

| 18 | The dezir, a type of poem, was written by Ferrando Manuel de Lando around 1411 and offers an original profile of Ferrer, with a perfect representation of the aforementioned duality generated by the Dominican friar (De Baena 1851, pp. 163–65). |

| 19 | The rector does note that the observers believed they were listening to an angel sent by God, due to Ferrer’s oratorical skill, but there is no trace of any mention of the miracle. The expression used seems to be ascribable to the rhetoric of the time. |

| 20 | Excerpts of sermons given by Ferrer in Zaragoza indicate that he also used Catalan in the city (Chabás 1903, p. 111). |

| 21 | Though expressed in other terms and for a different purpose, this divergence between the letter and the Toledo sermon has already been signalled (García Mahiques 2011, pp. 220–21). |

| 22 | Before this, in May 1454 in Toulouse, during the process of canonizing Ferrer, Andrea de Fulcovisu declared that Christ had appeared to Ferrer in Perpignan. This was used as a source for one of the side panels of the Saint Vincent Ferrer polyptych from San Domenico Maggiore, Naples, attributed to Colantonio and now housed in the same city’s Museo di Capodimonte. It portrays an epiphany that is different to the Avignon vision, in that Saint Francis and Saint Dominic are not present (Calvé Mascarell 2016, pp. 483–84). |

| 23 | It seems appropriate to include the image of this idealized reconstruction of the float to observe how two different narratives transmitted through the three late medieval communication channels intermingled: the three spears of Christ ready to end the world and Vincent Ferrer’s own vision. Both stories were part of the preaching of the Dominican and the letter he sent to the pope. |

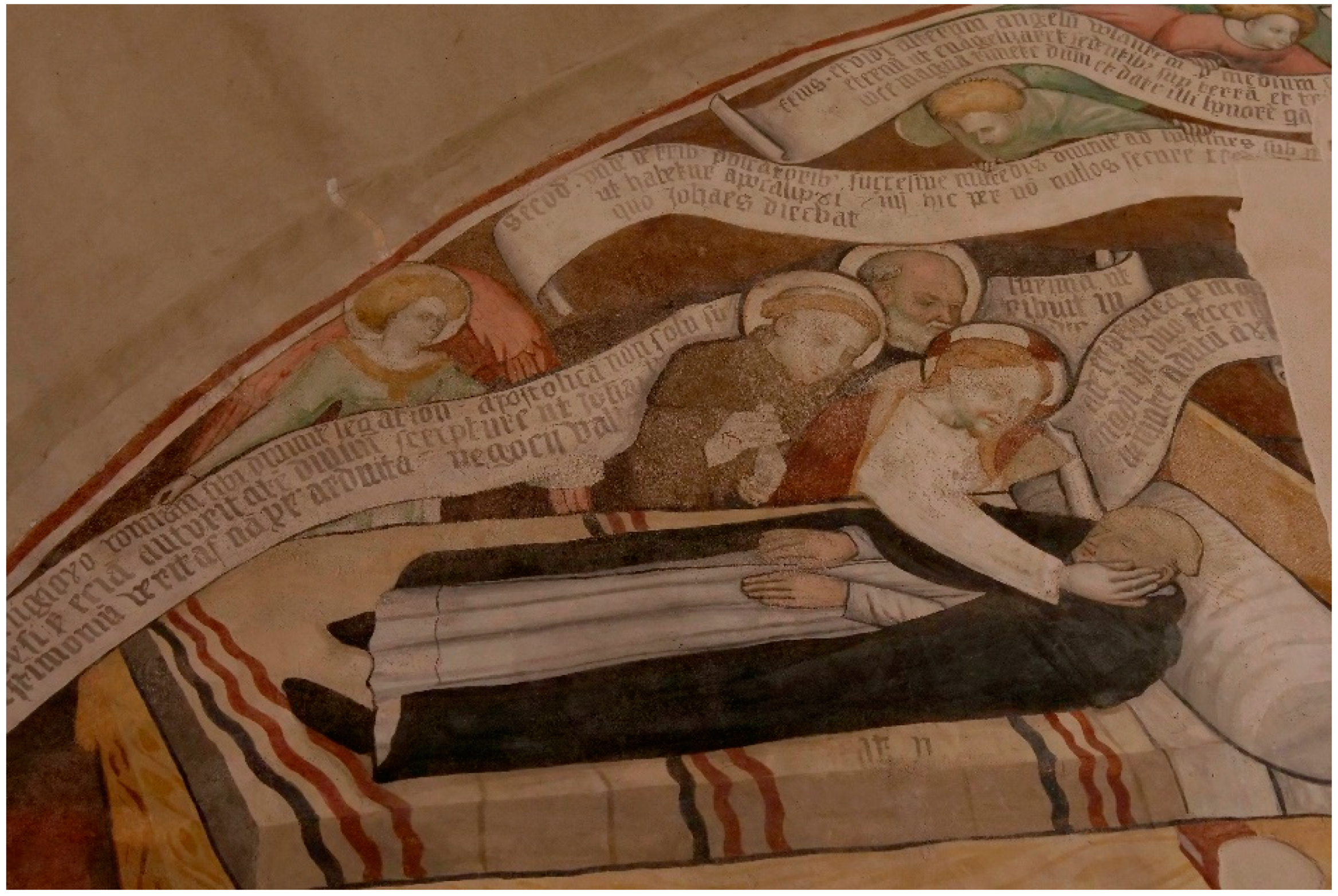

| 24 | Near Macello is the town of Scarnafigi. There, in the Cappella della Santissima Trinità, a fresco depicting Ferrer’s preaching is still preserved today. It was commissioned before 1455 by the friar Antonio de Vigone. |

| 25 | It must be noted that, between late 1412 and 1414, Ferrer declared that the tractat was within the reach of many. |

| 26 | In terms of the Schism, his ultimate reference point was Ferrer. The influence of Vincentian thought in the Statuto Sabaudo has been signalled (Iaria 2007, p. 333). |

| 27 | The most recent restoration was limited to the Vincentian cycle. It was carried out between late 2020 and early 2021 (Città metropolitana di Torino 2021). |

| 28 | With certain nuances regarding the collaborators (Bertolotto et al. 2011), specialists agree on the attribution of the painting. Bena Solaro del Borgo, daughter of Vasino Malabaila, was the first wife of Bonifacio II Solaro. They had at least four children, two of which, Marchetto and Francesco, had links to Macello (Angius 1841, p. 939). |

| 29 | The kneeling child may represent Marchetto, the son of Bonifacio II and Bena Solaro (Di Macco 1979, p. 400). |

| 30 | One sign of this was the compilation put together by Henri Le Médec for John V, Duke of Brittany. The latter sent it to Pope Martin V before 1422 to boost the canonization process (Le Grand 1901, p. 418; De Garganta and Forcada 1956, p. 266; Cassard 2006, p. 91). Perhaps this was the same collection of miracles that the Duke of Brittany later passed on to Henry of Trastámara, brother of Alfonso the Magnanimous. |

| 31 | On the bed, an inscription read “Beatus Vincentius” (Monetti 1978b). |

| 32 | Authors later pointed out that the cheek touched by Jesus Christ shone in a supernatural fashion in the sermons (Antist 1575, pp. 37–38; Vidal y Micó 1735, p. 286): a detail that had little impact on Vincentian iconography overall. |

| 33 | The angel holding the uppermost banderole was recovered in the most recent restoration. |

| 34 | The considerable similarity between the sermons given around 1411–1414 and the letter requires clarification: the textual development in both images coincides with the letter, and the slight transformations made to adapt the words to the space available and the potential small errors are insignificant. Therefore, only the translation of the letter will be provided here. |

| 35 | The second announces that Babylon has fallen and the third challenges those who worship he beast and its image (Rev 14:8–11). |

| 36 | For another of the panels, the “sermon given for the Pope, the emperor, and the king, counts and princes, and an infinite crowd of other people” was requested. |

| 37 | Such as in the aforementioned Vincent Ferrer panel made by Erri, the dove was used by Fra Angelico to portray Blessed Ambrose of Siena’s holy inspiration. On the same panel from the dismantled altarpiece from the Convent of Saint Dominic in Fiesole (1423), he depicted Beatus Vincentius with a flame in his hand. |

| 38 | Leaving any debates around dating aside, the comparison of the sermons reveals divergences in content that transcend the formal sphere, regardless of the specific production date. |

| 39 | As indicated, Placentis found out from Ferrer that he supported Pope Luna many years after this alleged falling out. |

| 40 | Another Vincentian vision during the canonization process, the alteration of the story in Ranzano’s vita, and the transformation of the story in the Legenda Aurea (including the omission of Saints Dominic and Francis) are all examples where the figure of Ferrer is the protagonist of the vision. The vita set the trend for subsequent historiography. |

References

- Ammann, Chantal, and Franco Morenzoni. 2019. De l’elaboration à la diffusion manuscrite des Statuta Sabaudie. In La loi du Prince. La raccolta normativa sabauda di Amedeo VIII (1430). Directed by Mathieu Caesar, and Franco Morenzoni. Torino: Deputazione subalpina di storia patria, pp. 23–86. [Google Scholar]

- Angius, Vittorio. 1841. Sulle famiglie nobili della monarchia di Savoia, I. Torino: Fontana e Isnardi. [Google Scholar]

- Antist, Vicente Justiniano. 1575. La vida y historia del apostólico predicador fray Vicente Ferrer. Valencia: Casa de Pedro de Huete. [Google Scholar]

- Baiocco, Simone, Simonetta Castronovo, and Enrica Pagella. 2003. Arte in Piamonte: Il Gotico. Ivrea: Priuli and Verlucca. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotto, Claudio, Nicoletta Garavelli, and Bernardo Oderzo Gabrielli. 2011. Magister Dux Aymo pictor de Papia. Un pittore pavese in Piemonte (notizie 1417–44). Arte Lombarda 163: 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Betí Bonfill, Manuel. 1922. El tratado de San Vicente Ferrer sobre el advenimiento del Anticristo. Boletín de la Sociedad Castellonense de Cultura 3: 134–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brizio, Anna Maria. 1942. La pittura in Piemonte dall’età romanica al Cinquecento. Torino: G.B. Paravia. [Google Scholar]

- Calvé Mascarell, Óscar. 2016. La configuración de la imagen de san Vicente Ferrer en el siglo XV. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Calvé Mascarell, Óscar. 2019. «L’entramès de Mestre Vicent»: Resplandor de la autoridad del Predicador. Anuario De Estudios Medievales 49: 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calvé Mascarell, Óscar. 2020. Beatus Vincentius en Santa Maria Assunta di Macello. Anales de la Real Academia de Cultura Valenciana 95: 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonero y Sol, León. 1873. Sermones de san Vicente Ferrer sobre el Anticristo. Sermón tercero. La Cruz 1: 145–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cassard, Jean-Christophe. 2006. Vincent Ferrier en Bretagne: Une tournée triomphale, Prèlude à una riche carrière posthume. In Mirificus praedicator. A l’occasion du sixième centenaire du passage de saint Vincent Ferrier en pays romand. Edited by Paul-Bernard Hodel and Franco Morenzoni. Rome: Institutum historicum fratrum praedicatorum, pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cátedra García, Pedro María. 1984. La predicación castellana de San Vicente Ferrer. Boletín de la Real Academia de Buenas Letras de Barcelona 29: 235–309. [Google Scholar]

- Cátedra García, Pedro María. 1994. Sermón, sociedad y literatura en la Edad Media. San Vicente Ferrer en Castilla (1411–1412): Estudio bibliográfico, literario y edición de los textos inéditos. Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León Consejería de Cultura y Turismo. [Google Scholar]

- Chabás, Roque. 1902. Estudio sobre los sermones valencianos de san Vicente Ferrer que se conservan manuscritos en la biblioteca de la basílica metropolitana de Valencia. 2. Originalidad de los Sermones. Recursos Oratorios. Fin á que se dirigían. Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos 6: 131–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chabás, Roque. 1903. Estudio sobre los sermones valencianos de san Vicente Ferrer que se conservan manuscritos en la biblioteca de la basílica metropolitana de Valencia. 5. Alusiones a sí mismo, a la compañía de penitencia, al rey de Aragón. Judíos y moros. Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos 8: 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chène, Catherine. 2006. La plus ancienne vie de Vincent Ferrier racontée par le dominicain allemand Jean Nider (ca. 1380–438). In Mirificus praedicator. A l’occasion du sixième centenaire du passage de saint Vincent Ferrier en pays romand. Edited by Paul-Bernard Hodel and Franco Morenzoni. Rome: Institutum historicum fratrum praedicatorum, pp. 121–66. [Google Scholar]

- Città metropolitana di Torino. 2021. Restauri d’arte: La cappella di Stella a Macello. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1Xasl3pQwU&list=PLvp_c1wxO4mQhnTBfhWl8VV7s0KnVYXdX&index=12 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- D’Arenys, Petrus. 1975. Chronicon. Edited by José Hinojosa Montalvo. Valencia: Anubar. [Google Scholar]

- D’Haenens, Albert. 1983. Écrire, utiliser et conserver des textes pendant 1500 ans: La rélation occidentale à l’écriture. Scrittura e civiltà 7: 225–60. [Google Scholar]

- Daileader, Philip. 2016. Saint Vincent Ferrer, His World and Life: Religion and Society in Late Medieval Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillian. [Google Scholar]

- De Alpartil, Martín. 1994. Cronica actitatorum temporibus Benedicti Pape XIII. Edited by J. Ángel Sesma Muñoz and Mª Mar Agudo. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón. [Google Scholar]

- De Baena, Juan Alfonso. 1851. Cancionero de Juan Alfonso de Baena. Edited by Pedro José Pidal y Carniado. Madrid: Rivadeneyra. [Google Scholar]

- De Garganta, José M., and Vicente Forcada, dirs. 1956. Biografía y escritos de San Vicente Ferrer. Madrid: La Editorial Católica. [Google Scholar]

- Di Macco, Michela. 1979. Scheda Dux Aymo, 1429. In Giacomo Jaquerio e il gotico internazionale. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo e Giovanni Romano. Torino: Assessorato per la Cultura - Musei Civici, pp. 398–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle, Franz, ed. 1900. Die Chronik des Garoscus de Ulmoisca Veteri und Bertrand Boysset (1365–1415). Der bekannte lang andauernde Zwist der Armagnacs und Bourguignons 7: 311–420. [Google Scholar]

- Esponera Cerdán, Alfonso, ed. 2005. San Vicente Ferrer. Vida y escritos. Madrid: Edibesa. [Google Scholar]

- Fagês, Henri-Dominique. 1903. Historia de San Vicente Ferrer. Translated by Antonio Polo de Bernabé. Valencia: A. García, volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fagês, Pierre-Henry. 1905. Notes et documents de l’histoire de Saint Vincent Ferrier. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster Perelló, Sebastián, ed. 2007. Proceso de Canonización de San Vicente Ferrer. Declaraciones de los testigos. Sebastián Fuster, trans. Valencia: Ajuntament de València. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffuri, Laura. 2006. «In partibus illis ultra montanis». La missione subalpina di Vicent Ferrer (1402–1408). In Mirificus praedicator. A l’occasion du sixième centenaire du passage de saint Vincent Ferrier en pays romand. Edited by Paul-Bernard Hodel and Franco Morenzoni. Rome: Institutum historicum fratrum praedicatorum, pp. 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffuri, Laura. 2020. Predicatori tra città e corte nel Piemonte sabaudo del Quattrocento. In Prêcher dans les espaces lotharingiens. XIII-XIX siècles. Directed by Stefano Simiz. Paris: Classiques Garnier Multimedia, pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffuri, Laura. 2021. Frati in trincea. Felice V (Amedeo VIII di Savoia), gli ordini mendicanti e lo scisma di Basilea (1439–1449). Rivista di Storia della Chiesa in Italia 1: 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- García Mahiques, Rafael. 2011. El discurs visual de Sant Vicent Ferrer en la visió d’Avinyó per Francesc Ribalta. In Cartografías visuales y arquitectónicas de la modernidad: Siglos XV–XVIII. Edited by Sílvia Canalda i Llobet. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, pp. 209–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno Blay, Francisco M. 2019. Modelos de transmisión textual de los sermones de San Vicente Ferrer: La tradición manuscrita. Anuario De Estudios Medievales 49: 137–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorce, Maxime M. 1923. Les Bases de l’étude historique de saint Vincent Ferrier. Paris: Plon-Nourrit et Cie. [Google Scholar]

- Griseri, Andreina. 1965. Jaquerio e il realismo gotico in Piemonte. Torino: Edizioni d’Arte Fratelli Pozzo. [Google Scholar]

- Hauf, Albert. 1983. Fr. Francesc Eixirnenis, O.F.M., “De la predestinación de Jesucristo”, y el consejo del Arcipreste de Talavera “a los que deólogos mucho fundados non son”. Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 76: 239–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, Paul-Bernard. 1993. Sermons de saint Vincent Ferrier a Estavayer-le-Lac en mars 1404. Mémorie dominicaine 2: 149–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, Paul-Bernard. 2005. La lettre de saint Vincent Ferrier a Benoît XIII. Escritos del Vedat 35: 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, Paul-Bernard. 2006. D’une édition à l’autre: La lettre de saint Vincent Ferrier à Jean de Puynoix du 17 décembre 1403. In Mirificus praedicator. A l’occasion du sixième centenaire du passage de saint Vincent Ferrier en pays romand. Edited by Paul-Bernard Hodel and Franco Morenzoni. Rome: Institutum historicum fratrum praedicatorum, pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel, Paul-Bernard. 2007. La lettre de Saint Vicent Ferrier au pape Benoít XIII. In El fuego y la palabra. San Vicente Ferrer en el 550 aniversario de su canonización. Edited by Emilio Callado Estela. Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Iaria, Simona. 2007. Ritratto di un antipapa: Amedeo VIII di Savoia (Felice V) negli scritti di Enea Silvio Piccolomini (Pio II). Annali di studi religiosi 8: 323–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ivars, Andrés. 1925. El escritor fr. Francisco Eixeménez en Valencia (1383–1408). Archivo Ibero-Americano 24: 325–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kaftal, George. 1985. Iconography of the Saints in Italian Painting, Vol. 4. Iconography of the Saints in the Painting of North West Italy. Firenze: Le lettere, vol. 660–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevsky, Sophie. 2002. Iconographie de saint Vincent Ferrier dans les Alpes méridionales. In D’une montagne à l’autre. Êtudes compares. Edited by Dominique Rigaux. Grenoble: PREALP-CRHIPA, pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand, Albert. 1901. Les vies des saints de le Bretagne armoricque. Quimper: J. Salaün. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, Carolina M. 2019. Vicent Ferrer, misionero apocalíptico. Sobre el uso de la pedagogía del terror en sus sermones medievales hispanos. Anuario De Estudios Medievales 49: 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, William Paul. 1996. Carthusian Policy and the Council of Basel. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Madurell i Marimon, Josep Maria. 1945. El arte en la comarca alta de Urgel. Anales y Boletín de los Museos de Arte de Barcelona III–IV: 259–340. [Google Scholar]

- Madurell i Marimon, Josep Maria. 1968. Manuscrits eiximenians. Petit repertori documental. In Martínez Ferrando Archivero. Miscelánea de estudios dedicados a su memoria. Edited by Asociación Nacional de Bibliotecarios, Archiveros y Arqueólogos. Barcelona: Asociación Nacional de Bibliotecarios, Archiveros y Arqueólogos, pp. 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Ferrando, Jesús Ernesto. 1955. San Vicente Ferrer y la Casa Real de Aragón. Documentación conservada en el Archivo Real de Barcelona. Barcelona: Balmesiana. [Google Scholar]

- Massó Torrents, Jaume. 1910. Les obres de fra Francesc Eiximenis (1340?–1409?). Essaig d’una bibliografía. Anuari de l’Institut d’Estudis Catalans 3: 1–107. [Google Scholar]

- Monetti, Franco. 1978a. Preziosi affreschi a La Stella. Il primo ciclo pittorico su S. Vincenzo Ferreri. Piemonte Vivo 1: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Monetti, Franco. 1978b. Una documentazione della presenza di Vincenzo Ferreri nel Pinerolese. Studi Piemontesi 7: 386–87. [Google Scholar]

- Montagnes, Bernard. 1988. La guérison miraculeuse et l’investiture prophétique de Vincent Ferrier au couvent des frères Prêcheurs d’Avignon (3 octobre 1398). In Avignon au Moyen Âge: Textes et documents. Edited by Institut de recherches et d’études du bas Moyen âge avignonnais. Avignon: Aubanel, pp. 193–98. [Google Scholar]

- Morenzoni, Franco. 2004. La prédication de Vincent Ferrier à Montpellier en Décembre 1408. Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum 74: 225–71. [Google Scholar]

- Morerod, Jean-Daniel. 2006. Les étapes de Vincent dans le diocèse de Lausanne. In Mirificus praedicator. A l’occasion du sixième centenaire du passage de saint Vincent Ferrier en pays romand. Edited by Paul-Bernard Hodel and Franco Morenzoni. Rome: Institutum historicum fratrum praedicatorum, pp. 259–84. [Google Scholar]

- Narbona Vizcaíno, Rafael. 2018. Viure la València de Sant Vicent Ferrer. Paper presented at the Meeting Clàssics a La Nau. Els Dijous de Sant Vicent Ferrer, Universitat de València, València, Spain, October 25. [Google Scholar]

- Perarnau i Espelt, Josep. 1989. L’antic mss. 279 de la catedral de València, amb sermons de sant Vicenç Ferrer, perdut durant la guerra del 1936–39. Intent de reconstrucción. Butlletí de la Biblioteca de Catalunya 10: 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Perarnau i Espelt, Josep. 1999a. Els manuscrits d’esquemes i de notes de sermons de Sant Vicent Ferrer. Arxiu de textos catalans antics 18: 158–398. [Google Scholar]

- Perarnau i Espelt, Josep. 1999b. Les Primeres «reportaciones» de sermons de st. Vicent Ferrer: Les de Friedrich von Amberg, Friburg, Cordeliers, ms. 62. Arxiu de textos catalans antics 18: 63–155. [Google Scholar]

- Perarnau i Espelt, Josep. 2003. La (Darrera?) quaresma transmesa de sant Vicent Ferrer: Clarmont-Ferrand, BMI, Ms. 45. Arxiu de Textos Catalans Antics 22: 343–550. [Google Scholar]

- Ranzano, Petro. 1866. Vita sancti Vicentii Ferreri. In Acta Sanctorum. Aprilis, tomus primus. Edited by Société des Bollandistes. Paris: Parisiis et Romae apud Victorem Palme, pp. 481–510. [Google Scholar]

- Robles Sierra, Adolfo. 1996. Obras y escritos de San Vicente Ferrer. Valencia: Ajuntament de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Leal, Salvador. 2016. Carta de Vicente Ferrer a Benedicto XIII sobre el anticristo: Apuntes sobre la versión española. In Texto, género y discurso en el ámbito francófono. Edited by Tomás Gonzalo Santos. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 341–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi, Roberto. 1978. Fonti e documenti su Manfredi da Vercelli O.P. e il movimiento penitenziale dei terziari manfredini. Archivum Fratrum Praedicatorum 48: 93–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi, Roberto. 1999. Profezia e profeti alla fine del Medioevo. Roma: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Vincent Ferrer. 1971. Sermons. Volum segon. Edited by Josep Sanchis Sivera. Barcelona: Barcino. First published 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Vincent Ferrer. 1973. Sermons de Quaresma I. Edited by Manuel Sanchis Guarner. Valencia: Albatros Edicions. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Vincent Ferrer. 1988. Sermons. Volum sisè. Edited by Gret Schib. Barcelona: Barcino. [Google Scholar]

- San Vicente Ferrer. 2002. Sermonario de San Vicente Ferrer del Real Colegio-Seminario de Corpus Christi de Valencia. Edited by Francisco Gimeno Blay and Mª Luz Mandingorra Llavata. Translated by Francisco Calero Calero. Valencia: Ayuntamiento de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- San Vicente Ferrer. 2006. Sermonario de Perugia (Convento dei Domenicani, ms. 477). Edited by Francisco M. Gimeno Blay and Mª Luz Mandingorra Llavata. Valencia: Ajuntament de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- San Vicente Ferrer. 2009. Sermones de Cuaresma en Suiza, 1404. Edited by Francisco M. Gimeno Blay and Mª Luz Mandingorra Llavata. Valencia: Ajuntament de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Société Archéologique de Montpellier, ed. 1840. Thalamus parvus. Le petit Thalamus de Montpellier. Montpellier: Jean Martel Ainé. [Google Scholar]

- Teixidor, Joseph O. P. 1999. Vida de San Vicente Ferrer, Apóstol de Europa. Edited by Alfonso Esponera Cerdán. Valencia: Ayuntamiento de Valencia, volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Teoli, Antonio. 1738. Storia della vita, e del culto di S. Vincenzo Ferrerio dell’Ordine de Predicatori. Napoli: Felice Carlo Mosca. [Google Scholar]

- Toldrà i Vilardell, Albert. 2006. Mestre Vicent ho diu per spantar. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Treccani. 2019. Solaro del Borgo. Enciclopedia italiana. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/solaro-del-borgo_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Vidal y Micó, Francisco. 1735. Historia de la portentosa vida, y milagros del Valenciano Apóstol de Europa S. Vicente Ferrer. Valencia: Oficina de Joseph Estevan Dolz. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, Paul. 1989. La letra y la voz. De la «literatura medieval». Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

| Text from the Frescoes in Macello | Text from the Epistle to Benedict XIII * |

|---|---|

| (V)ade et p(re)dica per mo(ndum) a | religioso infirmo, quod ipse iret per mundum apostolice predicando |

| (quemad)modum isti duo fecerunt (ut) | quemadmodum praedicti sancti fecerant et |

| (convertes) eum ante adventum antichristi | sic eius predicationem ante adventum Antichristi ad conversionem |

| Text from the Frescoes in Macello | Text from the Epistle to Benedict XIII * |

|---|---|

| Primus: Uti religioxo (commisam) sibi divinitus (legationem) apostolicam non solum si(gna pl)urima ut | Cui religioso comissam sibi divinitus legationem apostolicam diligenter exempti divina providentia, non solum signa plurima ut |

| Moysy sed eciam auctoritatem divin(ae Script)ure ut Johannis tribuit in | Moysy, sed etiam auctoritatem divine Scripture ut Iohanni Babtiste, tribuit in |

| testimonium veritatis nam propter arduit(atem) negocii datum (f)uit | testimonium veritatis, nam, propter arduitatem negotii et propter parvitatem sui testimoniis, plurium indigebat. |

| Text from the Frescoes in Macello | Text from the Epistle to Benedict XIII * |

|---|---|

| Secundus: unde de tribus predicatoribus successive mittendis divinitus ad homines sub n(ominibus Angelo)rum | Unde de 3bus predicatoribus succesive mittendis divinitus ad homines ante diem iuditii sub nominibus angelorum, |

| ut habetur apoca(lipsys) (cº.) XIIII hic per nonnullos sicure cre(ditur ese ille primus de) quo Ioannes dicebat | ut habetur Apoc 14, [6,7], ipse per nonnullos secure creditur esse ille primus de quo Iohannes dicebat: |

| Text from the Frescoes in Macello | Text from the Epistle to Benedict XIII * |

|---|---|

| Tercius: et vidi alterum Angelum volantem per medium ce(li ha)bentem evang(e)lium | “Et vidi alterum angelum volantem per medium celi, habentem Evangelium |

| eternum ut evangelizaret sedentibus super terram et tri(bum et lingu)a et populum dice(n)s | eternum, ut evangelizaret sedentibus super terram, et super omnem gentem, et tribum, et linguam, et populum: dicens |

| voce magna timete dominum et date illi honorem quia (venit h)ora (i)udicii eius qui potest capere capia(t) | magna voce: Timete Dominum, et date illi honorem, quia venit hora iuditii eius” etc. Qui potest capere capiat. |

| Text from the Frescoes in Macello | Text from the Epistle to Benedict XIII * |

|---|---|

| (Unde co)lligitur | Unde ex omnibus supradictis colligere |

| (in m)ente mea opi | in mente mea oppi- |

| (nio) et credencia (veri) | nio et credentia veri |

| (si)milis (licet) non sce(n)c (ia certa et) | similis, licet non scientia certa, et |

| (pre)dicabilis de na(tivitate antichristi) | praedicabilis de nativitate Antichristi iam transacta per 9 annos. |

| Attamen (dictam?) conclu(sionem quae dicit quod cito) | Attamen, predictam conclusionem que dicit quod cito et bene cito, |

| ac valde breviter e(runt tempus antichristi et finis Mundi) | ac valde breviter, erunt tempus Antichristi et finis Mundi certitudinaliter |

| vidi secure ac s(ecure praedico u)bique | ac secure predico ubique. |

| domino chuoperante et (sermonem confirmante se)quentibus signis. | Domino cooperante et sermonem confirmante sequentibus signis: |

| Verum dominus noster yhs x(st)us presciens hanc doctrinam | Verum, Dominus noster Iesus Christus, presciens hanc doctrinam |

| sive concluxionem ab amatoribus huius mundi sive carnalibus | seu conclusionem ab amatoribus huius mundi et carnalibus |

| (per)sonis minime recipendiam, dicebat luce XVII edebant | personis minime recipiendam, dicebat, Lc capitulo 17, [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]: “Sicut factum est in diebus Noe, ita erit in diebus Filii hominis. Edebant |

| (et b)ibebant uxores duceb(an)t et dabantur ad nupcias unque in diem qua | et bibebant: uxores ducebant et dabantur ad nuptias, usque in diem, qua |

| Noe (in)travit in archam (s)imi(li)ter sicut factum fuit in diebus Lot, (ita) erit in diebus | intravit Noe in archam: et venit diluvium, et perdidit omnes. Similiter sicut factum est in diebus Loth: Edebant et bibebant, emebant et vendebant, plantabant, et edificabant: |

| filii hominis | qua die autem exivit Loth a Sodomis, pluit ignem, et sulfur de celo, et omnes perdidit: secundum hec erit qua die Filius hominis revelabitur. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calvé Mascarell, Ó. Vincent Ferrer’s Vision: Oral Traditions, Texts and Imagery. Religions 2022, 13, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100940

Calvé Mascarell Ó. Vincent Ferrer’s Vision: Oral Traditions, Texts and Imagery. Religions. 2022; 13(10):940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100940

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalvé Mascarell, Óscar. 2022. "Vincent Ferrer’s Vision: Oral Traditions, Texts and Imagery" Religions 13, no. 10: 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100940

APA StyleCalvé Mascarell, Ó. (2022). Vincent Ferrer’s Vision: Oral Traditions, Texts and Imagery. Religions, 13(10), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100940