Christianity and Liberation: A Study of the Canadian Baptist Mission among the Savaras in Ganjam (Orissa), c.1885–1970

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Conversion is paradoxical. It is elusive. It is inclusive. It destroys and it saves. Conversion is sudden and it is gradual. It is created totally by the action of God, and it is created totally by the actions of humans. Conversion is personal and communal, private, and public. It is both passive and active. It is a retreat from the world. It is a resolution of conflict and an empowerment to go into the world and confront, if not create, conflict. Conversion is an event and a process. It is an ending and a beginning. It is final and open-ended. Conversion leaves us devastated and transformed.

“.... feeling that the most progressive theology in Latin American is more interested in being liberative than talking about liberation. In other worlds, Liberation theology deals not so much with content as with the method used to theologize in the face of our real-life situation”.

“Liberation theology is not the application of traditional theology to a different theological agenda including exotic phenomena such as revolution. It is a Theology done through a completely different method”.

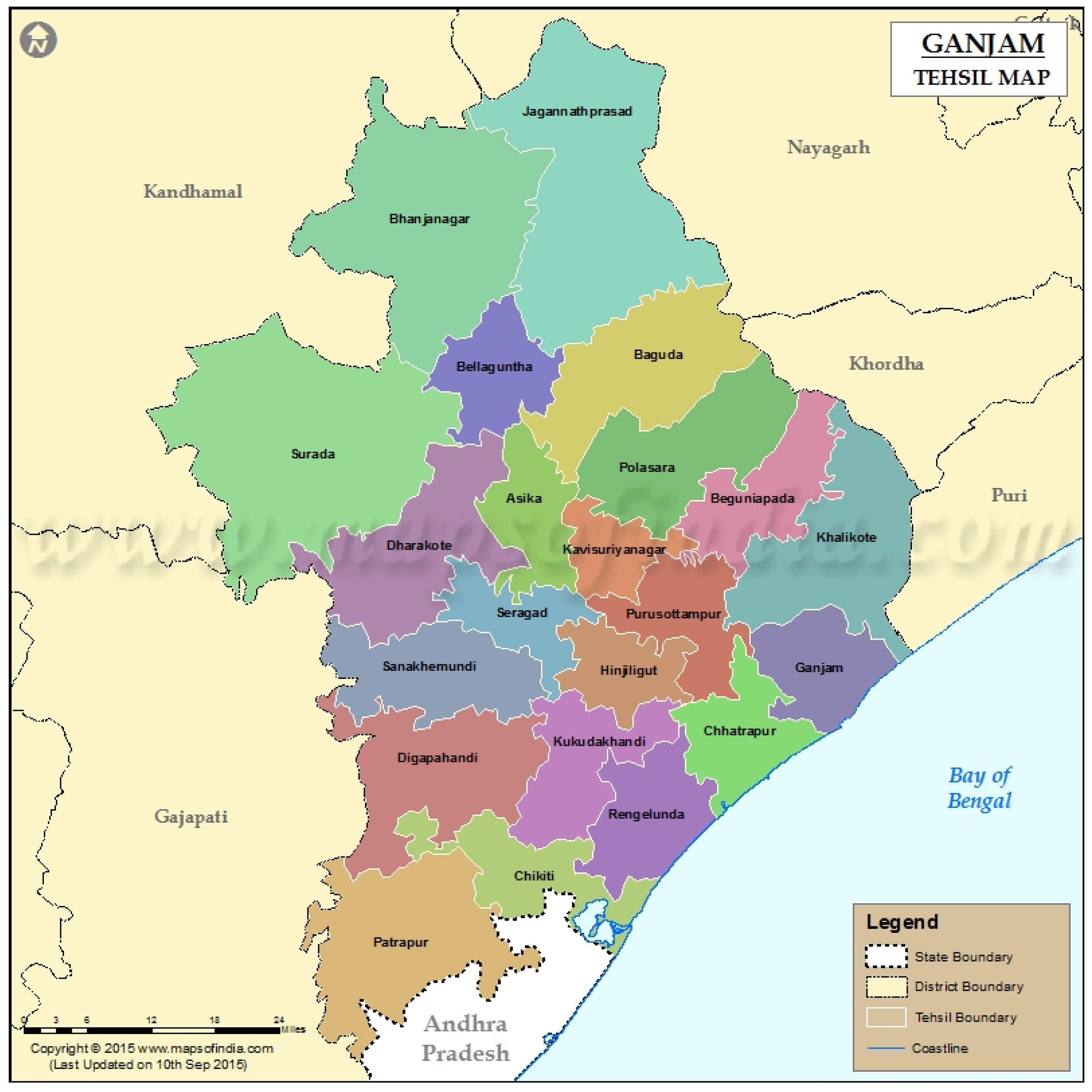

2. The Rural World of Ganjam

Panos are bad men. But they have a finger in every pie. I had to pay Rs.600 to save my land from ceiling laws through Barik Jogi Goenta (the biggest Pano fortune-maker). We always live on the brink of death and we have to tolerate them…in everything that we do, they outwit us. If we resort to violence, the police will not leave us. I suppose we chase away the Panos.

3. Arrival of the Canadian Baptist Mission and Their Contributions in Ganjam

4. Christian Conversion Movement among the Savaras and Its Consequences in Ganjam

5. Christianity as a Countenance of Liberative Theology

That type of spiritual growth or development which involves an appreciable change of direction concerning religious ideas and behaviour. Most clearly and typically, it denotes an emotional episode of illuminating suddenness, which may be deep or superficial, though it may also come about by the more gradual process.

As the oppressors dehumanize others and violate their rights, they themselves also become dehumanised. As the oppressed, fighting to be human, take away the oppressors’ power to dominate and suppress, they restore to the oppressors the humanity they had lost in the exercise of oppression. It is only the oppressed who, by freeing themselves, can free their oppressors. The latter, as an oppressive class, can free neither others nor themselves.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The tribal and Dalit (untouchable) Christians felt that the Indian Christian theology served the interests of the elite sections of the population. This initiated counter theology in the name of Indian Dalit theology that affirmed and confirmed the aspirations and needs of the marginalized people (Daughrity and Athyal 2016; Massey 2014). |

| 2 | The prevailing caste system in India is the system of four varnas, each comprising several endogamous castes and sub-castes (jatis) in the Hindu society. Each of these have their specified hereditary occupation. The four varnas are Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (soldiers), Vaishyas (traders), and Sudras (servants). People outside these varnas are called avarnas, Ati-Sudras, are arranged in their own hierarchies as the untouchables, the unseeable, and the unapproachable (Roy 2016). |

| 3 | The traditional beliefs about natural calamities like heavy rains, thunder and lighting, and earthquakes were that they were caused by demons. Therefore, during storms the locales would seek mercy from the Great God; when epidemics broke out, the Savaras believed that the evil spirits were pouring poisons from the top of trees or mountains, while the wind played carrier of those, thus ailing children (Paik 1910). |

| 4 | The Savara pantheon consisted of Lobosonum (female deity for good harvest), Karnasonum (male deity for good harvest of mango), Jenaangloo (village god or Kittung; a new harvest crop is first offered to the god before personal consumption), Ratusonum (male deity responsible for road safety), Edaisonum (ancestor god responsible for fever and Khudan sacrifices of a hen, goat, or beef before the house for propitiation), Lodasonum (forest deity), Rogasonum (both male and female in character worshipped to avoid breaking small pox), Karnisonnum (malevolent devil both male and female in character, and the Khudan offered pigs as sacrifice), Gangasonum (malevolent deity, female in character, worshipped to prevent drought and endemic diseases), Surendasonum (male in character, worshipped to keep away pests from the crops), Illasonum (devil responsible for consecutive miscarriages of a woman), Gagir-a-Bulu (devil responsible for creating ailments at the time of delivery; the shamanin offered hen, goats, or clothes for propitiation), and Sadru or Maandua (benevolent male god). In some areas, illness and diseases were linked to the symbols of colonialism. The Savaras created a new god Sahibosum, the Sahib (white man) god. Most probably, Sahibosum was a torturing official, a forest guard, or policeman, who was looked upon as a cholera carrier. The Savara carved wooden images in his honor and placed them at the outskirts of their villages to keep him out or at least divert his attention. Sacrifices were even performed for Sahibosum as it was essential to keep him happy (Tribal Myths of Orissa, Elwin 1954; Pati 2001). |

| 5 | ‘Purity and pollution,’ a concept presented by Louis Dumont, weaved his theory around the four-fold Indian caste system. He tried to establish the fact that a person’s ritual purity depended on the caste he was born to. Thus, for him, it was the caste rank that decided the degree of purity and pollution. Therefore, the untouchables belonging outside the caste hierarchy are the most polluting group in the society (Dumont 1980). |

| 6 | On every Saturday and Sunday, the Savaras used to visit the weekly markets in Parlakimedi where the missionaries used to preach the Gospel to them. Freeman expressed that they used to sell books and distribute pamphlets during the Hindu festival of Rathyatra (the ‘Car Festival’ of Lord Jagannatha). The missionaries used to stand amidst people, sing in Oriya and Savara, and share the word of God, which attracted the local people towards them. Dr. West, who arrived in 1919, carried out special evangelistic campaigns in the church, streets, homes of the sick, and in weekly markets (Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1910 1911; Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1923–1924). |

| 7 | The Protestant missionaries believed that medical mission was the most important agency to reach the rural inhabitants. It functioned like a ‘kindergarten system for preaching the message of the Gospel’ (Basu 2013). |

| 8 | The Ganjam Mala Odiya Baptist Church Association was founded with the support of four main churches and some of the sub-churches in Serango. In the beginning, the Savaras worshipped with the Panos without any hesitation or conflict. However, during the 1940s, with the spread of Christianity among the Savaras, they felt a need for a separate church. Out of the seventy-six respondents among both the Savaras and the Panos, all of them preferred a separate church because of linguistic and socio-cultural dissimilarities (Report of the Saora Church 1947, Field News-India; Set-1, Box 1 1948). |

| 9 | A person near Rayagada took baptism in 1922 after recovering from a chronic fever (Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1921–1922 1923). |

| 10 | Medical women were pious females extensively associated with, and having more actively participated in, promoting evangelical activities (Brouwer 1990). |

| 11 | While Turnbull was discoursing about eternal life and heaven to a group of Savaras in the open air, he reported: Suddenly someone shouted ‘airplane’ or ‘flying house’ as they called it. All the audience was at once in the middle of the street gazing upward, “see, see there it is- up very high,” and they watched it until it disappeared. Then as they settled down on the veranda again to hear the finish of the wonderful story, I was telling them, one man in all seriousness asked, “do your country people go to the eternal life heaven in airplanes?” (Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1942 1943). |

| 12 | One day, the Gumma zamindar (landlord), out of resentment, beat some Christians severely. These frightened the latter and they decided to complain to the missionary. Glendinning met them on his way, bound their wounds, and recorded their complaints. Then he called on the landlord. The Raja admitted his fault and sought for forgiveness, lest the missionary would have lodged a complaint with the police (Proceedings Nos. 81–82, July 1925 1926). |

| 13 | I borrow the concept of ‘popular’ from Sumit Sarkar who used ‘popular’ for the tribal people (along with the peasant and agrarian class) (Sarkar 1983). |

| 14 | Hindu cultural supremacy is the ascendance of dominant Brahminic forms of culture and, after India’s independence in 1947, Hindutva has made the unification of Hindus as a central agenda of its political aspirations. V.D. Savarkar reaffirmed this belief by stating that the Hindus “constitute the foundation, the bedrock, the reserved forces of the Indian state”. This synonymized India as Hindu Rashtra or State, and vice versa. So, to Hindutva, every conversion to Christianity indicated a loss in the battle for creating a Hindu majoritarian state (Chatterji 2009; Froerer 2012 (second impression); Chatterji et al. 2019). |

| 15 | The Christian missionaries were alleged to proselytize people with money power, allure the ignorant sections of the Hindu population, and displace Indian traditions by replicating western cultural patterns through the conduits of conversion. The attacks were generally hurled by the dominant sections of the society, and not the dominated ones. It was also pointed out that the missionaries took advantage of natural calamities like drought and famine when they posed themselves as saviors, which led people to convert (Lobo 1991). |

| 16 | This famous poem was written by Rudyard Kipling as a response to the American takeover of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War and projected the responsibility of white men in civilizing people of the culturally ‘backward’ country (Kipling n.d.). |

| 17 | A religious option can offer a wide range of emotional gratifications starting from developing a sense of solidarity, and relief from guilt, to building new relationships (Rambo 1993). |

| 18 | As a method of approach, the National Christian Council proposed that the only feasible practice was to select certain areas as demonstration centers and carry out evangelical works there. The main objectives were—firstly, development of Christian character, fellowship and service; secondly, enabling healthy living in a healthy environment; thirdly, improvement of family life through sanitation and child-care facilities; fourthly, enhance economic condition of people in villages; fifthly, maintain a cordial social attitude towards the neighbors and create an environment of social cooperation; sixthly, the constant re-creation of personality involving physical, mental, and spiritual attributes. Kenyon L. Butterfield proposed ten types of services in rural India—firstly, proclaiming Christianity through preaching and friendship; secondly, promoting religious education both to the Christians and non-Christians; thirdly, establishing village schools; fourthly, ministry of healing; fifthly, providing economic and social relief; sixthly, play and recreation; seventhly, helping the home-makers; eighthly, providing mass education; ninthly, establishing rural organisations; tenthly, training indigenous leaders (Manshardt 1933). |

References

- Abeyasingha, N. 1979. Indian Approaches to the Theology of Liberation. New Blackfriars 60: 270–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, Manoranjan. n.d. Religious Beliefs and Practices: A Case Study of Saoras of Gajapati District. In Tribal Culture in Transition. Edited by Trilochan Misra, Debi Prasanna Pattanayak and Bimalendu Mohanty. Bhubaneswar: Utkal University of Culture, pp. 69–72.

- Allaby, Edith. 1932. Research Notes: Among the Telugus 1930–1931. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press (Walter C. Koerner Library, University of British Columbia). [Google Scholar]

- Allaby, Edith. 1943a. Research Notes: Dr West’s Report (Serango Hospital) 1942. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press (William C. Mearns Centre for Learning-McPherson Library, University of Victoria, British Columbia), pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Allaby, Edith. 1943b. Research Notes: Turnbull’s Report 1942. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, Susanta Kumar. 2007. Agrarian Problem, Peasant and National Movement in Orissa. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 68: 944–54. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, Raj Sekhar. 2013. Healing the Sick and the Destitute: Protestant Missionaries and Medical Missions in 19th and 20th Century Travancore. In Medical Encounter in British India. Edited by Deepak Kumar and Raj Sekhar Basu. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Bayly, Susan. 1989. Saints, Goddesses and Kings. Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, Mohan. 1991. The Jayantira Pano: A Scheduled Caste Community of Orissa. Bhubaneswar: Tribal and Harijan Research-Cum-Training Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Behuria, Nrusinha Charan. 1992. Orissa District Gazetteers: Ganjam. Cuttack: Stationery and Publication, Government of Orissa. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, Barbara M. 1996. The Khonds: Human Sacrifice and Religious Change. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, Ruth Compton. 1990. New Women for God: Canadian Presbyterian Women and India Missions, 1876–1914. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, Glenn R. 1976. Toward a Liberation Theology for the “Oppressor”. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 44: 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, Henriette. 1994. Mission and Tamil Society: Social and Religious Change in South India (1840–1900). Surrey: Curzon Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Carder, W. Gordon. 1940. Christian Medical Service in Serango. Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Carder, W. Gordon. 1950. Serango-The Saoras: General Work. Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 2, 17, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Carder, W. Gordon. 1951. Medical Service in Serango. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carder, W. Gordon. 1961. Christian Medical Service in Serango. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Cederlof, Gunnel. 1997. Bonds Lost: Subordination, Conflict and Mobilisation in Rural South India c.1900–1970. New Delhi: Rajkamal Electric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centennial ‘Great Things’ 1968–1970 (CBOMB). 1971. Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 24–26.

- Chatterji, Angana P. 2009. Violent Gods: Hindu Nationalism in India’s Present-Narratives from Orissa. New Delhi: Three Essays Collective. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji, Angana P., Thomas Blom Hansen, and Christophe Jaffrelot. 2019. Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism Is Changing India. London: HarperCollins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cheria, Anita. 2014. The Church and the Adivasi-Towards Stronger Partnerships: With Reference to the Southern Regions and Islands. In Hearing the Voices of Tribals and Adivasis. Edited by Hrangthan Chhungi. Delhi: ISPCK/NCCI-COT, pp. 171–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chethimattam, John Britto. 1972. Towards a theology of liberation. Jeevadhara 2: 31. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Walter Houston. 1958. The Psychology of Religion. An Introduction to Religious Experience and Behaviour. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Sathianathan. 1998. Dalits and Christianity: Subaltern Religion and Liberation Theology in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Copley, Antony. 1997. Religions in Conflict: Ideology, Cultural Contact and Conversion in Late-Colonial India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Orville E. 1966. Rising Tides in India. Toronto: Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Orville E. 1973. Moving with the Times: The Story of Baptist Outreach from Canada into Asia, South America and Africa, During One Hundred Years, 1874–1974, Since the Canadian Baptist Mission was founded in India. Toronto: Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Bhaskar. 1983. Impact of the British Administration in Southern Orissa Zamindars. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 44: 409. [Google Scholar]

- Daughrity, Dyron B., and Jesudas M. Athyal. 2016. Understanding World Christianity: India. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devalle, Susana B. C. 1992. Discourses of Ethnicity: Culture and Protest in Jharkhand. New Delhi: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, Saurabh. 2004. Colonial Registers of a Vernacular Christianity: Conversion to Translation. Economic and Political Weekly 39: 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, Louis. 1980. Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and its Implications. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elwin, Verrier. 1954. Tribal Myths of Orissa. Bombay: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elwin, Verrier. 1955. The Religion of an Indian Tribe. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exley, Richard, and Helen Exley. 1973. The Missionary Myth—An Agnostic View of Contemporary Missionaries. Guildford and London: Lutterworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, Duncan. 1980. Caste and Christianity: Attitudes and Policies on Caste of Anglo-Saxon Protestant Missions in India. Wharton: Curzon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 1973. Education for Political Consciousness. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Froerer, Peggy. 2012. Religious Division and Social Conflict: The Emergence of Hindu Nationalism in Rural India. (Second Impression). New Delhi: Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric. 2003. Christians in India: An Historical Overview of Their Complex Origins. In Christians and Missionaries in India: Cross-Cultural Communication Since 1500. Edited by Robert Eric Frykenberg. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Glassie, Henry. 1995. Tradition. The Journal of American Folklore 108: 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, Sita Ram. 1986. Papacy: Its Doctrine and History. New Delhi: Voice of India. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, Gustavo. 1973. A Theology of Liberation. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, John R. 2000. Cultural Meanings and Cultural Structures in Historical Explanation. History and Theory 39: 331–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardgrave, Robert L. 1969. The Nadars of Tamilnad: The Political Culture of a Community in Change. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, David. 1987. The Coming of the Devi: Adivasi Assertion in Western India. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Christopher. 2008. Religious Transformation in South Asia: The Meanings of Conversion in Colonial Punjab. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hemrom, A. S. 2011. Empowerment of Adivasis/Tribals in India. In Critical Issues in Mission Among Tribals. Edited by Awala Longkumer. Delhi: ISPCK, pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, C. A. 1930. Report of C.A. Henderson in the Ganjam Administative Report of 1928–1929. Bhubaneswar: Orissa Government Press (Orissa State Archives). [Google Scholar]

- Horton, Robin. 1975. On the Rationality of Conversion. Africa 45: 219–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenifa, Rani S. 2013. A Reappraisal on Church’s Mission over Dalit Conversion and Dalit Christians’ Struggles by Taking in to Account Consideration of Hindutva’s Resistance. Bachelor’s thesis, United Theological College, Bangalore, India. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Dina Krishna. 2007. Lord Jagannath—The Tribal Deity. Orissa Review 80. [Google Scholar]

- Kappen, S. 1971. The Christian and the call to revolution. Jeevadhara 1: 39. [Google Scholar]

- Katoke, Israel K. 1984. Christianity And Culture: An African Experience. Transformation 1: 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, Alistair. 1987. Domination or Liberation? London: SCM, p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Mumtaz Ali. 1991. Mass Conversions of Meenakshipuram: A Sociological Inquiry. In Religion in South Asia: Religious Conversion and Revival Movements in South Asia in Medieval and Modern Times, 2nd revised ed. Edited by Geoffrey A. Oddie. New Delhi: Manohar, p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sebastian C. H. 2003. In Search of Identity: Debates on Religious Conversion in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kipling, Rudyard. n.d. The White Man’s Burden. Available online: https://ux1.eiu.edu/nekey/syllabi/british/kipling1899.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Konduru, Delliswararao. 2016. Ethnographic Analysis of Savara Tribe. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) 2: 985–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, Dick. 1989. Conversion and Social Equality in India: The London Missionary Society in South Travancore in the Nineteenth Century. New Delhi: Manohar Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurti, Yamini. 1993. What is Culture? World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues 2: 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, Lancy. 1991. Religious Conversion and Social Mobility: A Case Study of the Vankars in Central Gujarat. Surat: Centre for Social Studies, South Gujarat University Campus. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, George F. 1991. What Is Culture? The Journal of Museum Education 16: 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, L. K. n.d. Changing Religion and World View among the Tribes in India. In Tribal Culture in Transition. Edited by Trilochan Misra, Debi Prasanna Pattanayak and Bimalendu Mohanty. Bhubaneswar: Utkal University of Culture, p. 135.

- Malinowski, Bronisław. 1945. The Dynamics of Culture Change: An Inquiry into Race Relations in Africa. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manshardt, Clifford. 1933. Christianity in a Changing India: An Introduction to the Study of Missions. Calcutta: YMCA Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, James. 2014. Dalit Theology: History, Context, Text, and Whole Salvation. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, Bijay Chandra. 1927. The Aborigines of the Highlands of Central India. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. [Google Scholar]

- McLaurin, Mary S. 195? 25 Years on 1924–1949. Toronto: Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Sebastian Maria. 2015. Christianity and Cultures: Anthropological Insights for Christian Mission in India. Delhi: ISPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, P. Sanal. 2015. Modernity of Slavery: Struggles Against Caste Inequality in Colonial Kerala. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, Surendra K. 2002. The Impact of Protetsant Christianity on the Lives of Panos and Saoras in Ganjam District, Orissa, from 1902–1947. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Carey Library and Research Centre, Serampore, Indian; pp. 100–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, Sadananda. 2016. Christian History and Historiography: A Study of Odisha. Delhi: Shivalik Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Oddie, Geoffrey A. Oddie. 1977. Religion in South Asia: Religious Conversion and Revival Movements in South Asia in Medieval and Modern Times. London: Curzon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osuri, Goldie. 2012. Religious Freedom in India: Sovereignty and (Anti) Conversion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Padel, Felix. 2009. Sacrificing People: Invasions of a Tribal Landscape. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Pvt. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, Purna Chandra. 1910. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. CBOMB India, Box-2, 88–106; 88–179. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Panikkar, Kavalam Madhava. 1953. Asia Under Western Dominance: A Survey of the Vasco da Gama Epoch of Asian History, 1478–1945. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, Biswamoy. 2001. Situating Social History: Orissa 1800–1997. Delhi: New Delhi. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, Nityananda. 1989. The Saora. Orissa: Tribal and Harijan Research-cum-Training Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, Georg. 2014. Ethnographies of States and Tribes in Highland Odisha. Asian Ethnology 73: 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pickett, J. Waskom. 1933. Christian Mass Movement in India. Lucknow: Lucknow Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Proceedings (Home Department) Judicial 1926. 1927. Government Proceedings. New Delhi: Government of India (National Archives of India), pp. 11–12.

- Proceedings (Home-Judicial) of 1928. 1929. Government Proceedings. Bhubaneswar: Government of Orissa (Orissa State Archives), pp. 5–6.

- Proceedings Nos. 81–82, July 1925. 1926. Home Department, Judicial-A. New Delhi: Government of India (National Archives of India), July.

- Proceedings of the Judicial Department, Acc. No. 2275G: FL-1. 1878. Bhubaneswar: Governemnt of Orissa (Orissa State Archives).

- Raj, Ebe Sunder. 2004. Conversion: A National Debate. Delhi: Horizon Printers and Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, Lewis R. 1993. Understanding Religious Conversion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Chilkuri Vasantha. 2008. Jathara: A Festival of Christian Witness. Delhi: ISPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, Robert. 1955. The Social Organization of Tradition. The Far Eastern Quarterly 15: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1893. 1894. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Bhubaneswar: Orissa Mission Press (United Theological College Archives), pp. 25–26.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1905. 1906. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Bhubaneswar: Orissa Mission Press (United Theological College Archives), pp. 17–18.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1907. 1908. Report of Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Bhubaneswar: Orissa Mission Press, p. 17.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1908. 1909. Report of Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 18–19.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1910. 1911. Report of Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 33–36.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1911. 1912. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, p. 23.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1921–1922. 1923. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1930–1931. 1932. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press, pp. 11–13.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1942. 1943. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press (United Theological College Archives, Bangalore).

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1943. 1944. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press, pp. 20–21.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission 1966. 1967. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Cocanada: Canadian Baptist Mission Press, pp. 17–20.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Mission, July 1914–July 1915. 1916. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Cuttack: Orissa Mission Press (United Theological College Archives, Bangalore), p. 45.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Missionary (CBOMB 86–70 India) 1965. 1966. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University, pp. 17–20.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board, India, Bethel Hospital, Vuyyuru, 1939–1940. 1941. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Telugu Mission 1890–1949. 1950. Report of the Canadian Baptist Foreign Mission Board. Madras: SPCK, pp. 11–15.

- Report of the Canadian Baptist Telugu Mission 1902–1903. 1904. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Madras: SPCK (United Theological College Archives), p. 11.

- Report of the Saora Church 1947, Field News-India; Set-1, Box 1. 1948. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives (Walter C. Koerner Library, University of British Columbia), pp. 13–16.

- Report of the Saora-Oriya Work Committee: Evangelistic Cooperation in Western Ganjam, Orissa 1969–1970. 1970. Report of the Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University.

- Report of the Utkal Baptist Association 1930 (CBOMB-India). 1931. Canadian Baptist Overseas Mission Board. Hamilton: Canadian Baptist Mission Archives, School of Divinity Studies, McMaster University.

- Robinson, Francis. 2001. The Ulama of Farangi Mahall and Islamic Culture in South Asia. London: Hurst and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Rowena, and Sathianathan Clarke. 2003. Religious Conversion in India: Modes, Motivations, and Meanings. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Arundhati. 2016. The Doctor and the Saint. In Annihilation of Caste: The Annotated Critical Edition. Edited by Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. New Delhi: Navayana Publishing Pvt Ltd., p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ruether, Rosemarv. 1972. Liberation Theology. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, Sumit. 1983. ‘Popular’ Movements and ‘Middle Class’ Leadership in Late Colonial India: Perspectives and Problems of a ‘History from Below’. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Segundo, Juan Luis. 1976. The Liberation of Theology. New York: Orbis, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, Jayanta. 2015. At the Margins: Discourses of Development, Democracy, and Regionalism in Orissa. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Bhupinder. 1984. The Saora Highlander: Leadership and Development. Bombay: Somaiya Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Small Farmers Development Agency: District Ganjam. 1972. Cuttack: Agriculture Information Unit, Government of Orissa (Orissa State Archives).

- Srinivas, Mysore Narasimhachar. 1972. Social Change in Modern India. New Delhi: Orient Longman Limited. First Published in 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Suna, Nimai Charan. 2017. A Theology of Religious Freedom: An Engagement with the Odisha Freedom of Religion Act, 1967. In Religious Freedom and Conversion in India. Edited by Aruthuckal Varughese John, Atola Longkumer and Nigel Ajay Kumar. Bengaluru: SAIACS Press, pp. 186–212. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Birchell, and Burchell Taylor. 1991. The Theology of Liberation. Caribbean Quarterly 37: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, John. 1965. The Primal Vision. London: SCM. [Google Scholar]

- Thavare, Bhimrao S. 2000. Trends in the Theology of Conversion in India. In Conversion in a Pluralistic Context: Perspectives and Perceptions. Edited by Krickwin C. Marak and Plamthodathil S. Jacob. Delhi: ISPCK, pp. 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, Edgar. 1909. Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Madras: Government Press, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, V. 2008. Conversion Debate. Frontline 9: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, Gauri. 1998. Outside the Fold: Conversion, Modernity, and Belief. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, John C. B. 2007. The Dalit Christian: A History. Delhi: ISPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, John H. 1990. The Wider Setting of “Liberation Theology”. The Review of Politics 52: 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Basu Roy, T. Christianity and Liberation: A Study of the Canadian Baptist Mission among the Savaras in Ganjam (Orissa), c.1885–1970. Religions 2022, 13, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100996

Basu Roy T. Christianity and Liberation: A Study of the Canadian Baptist Mission among the Savaras in Ganjam (Orissa), c.1885–1970. Religions. 2022; 13(10):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100996

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasu Roy, Tiasa. 2022. "Christianity and Liberation: A Study of the Canadian Baptist Mission among the Savaras in Ganjam (Orissa), c.1885–1970" Religions 13, no. 10: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100996

APA StyleBasu Roy, T. (2022). Christianity and Liberation: A Study of the Canadian Baptist Mission among the Savaras in Ganjam (Orissa), c.1885–1970. Religions, 13(10), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100996