3. Historical Background

As

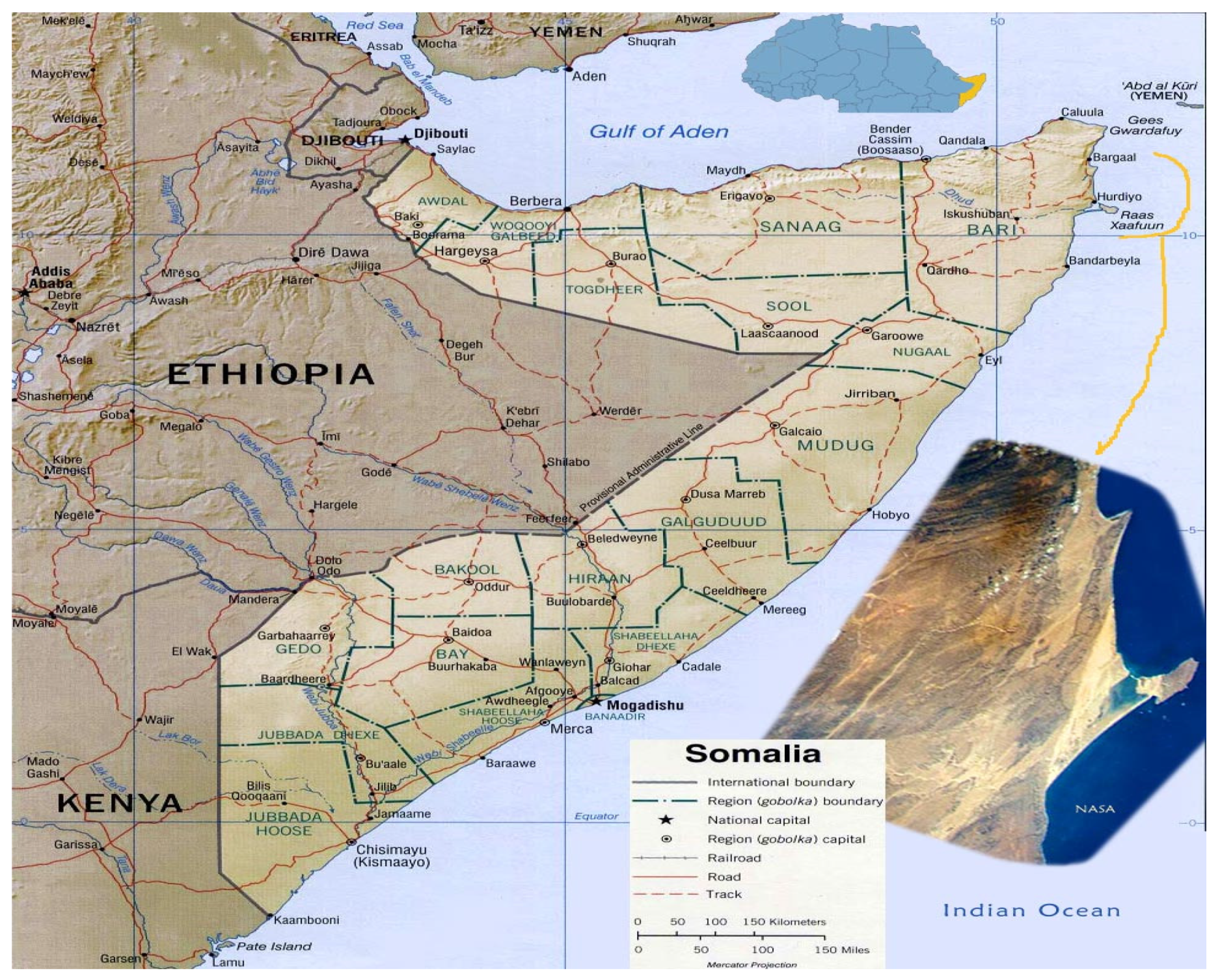

Figure 1 shows, Somalia is located on the Horn of Africa. Somalia is a tropical country and, except for a few places, is a country subject to frequent drought and famine (

Samatar 1982, p. 9). The below is the map of Somalia.

The Somalis are mainly an ethnic group that have traditionally lived in the Horn of Africa, stretching from the Awash Valley in Ethiopia, Djibouti, the Somali Republic, to beyond the River Tana in northern Kenya. The Somali people are, therefore, a nation rather than a state (

Middleton and Rassam 1995;

Lewis 1981).

It has been reported that Somalis, as well as the people of the Horn of Africa in general, embraced Islam early, perhaps even before it reached Madina Al-Munawarah

2 through the first migration from Mecca (the birthplace of Islam) to what was known at that time as

Ard al-Habasha (the land of Habasha, which might now include the entire Horn of Africa). This is where Prophet Mohamed advised the persecuted early Muslims in Mecca to migrate and seek refuge.

Secondly, subsequent migrants and traders from the Arabian Peninsula, such as those from Yemen and Oman, settled in urban areas, such as the coastal cities in the south of Somalia, including Mogadishu, Bawara, and Marka. These migrants and traders integrated into urban communities and facilitated them to contribute to teaching and spreading Islam (

Mukhtar 1995).

Mukhtar, a well-known scholar specialising in Somali history, argued that historical records demonstrate the formation of several ancient towns, markets, and urban centres that were established during large-scale Islamisation in Somalia (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 11). Academic reports confirm that traditional Somali religious scholars and teachers contributed greatly and at different times to the urbanisation of Somalia. For example, after receiving reasonable Islamic knowledge from their Islamic teachers and sheikhs, many of these newly graduated religious teachers returned to their nomadic tribes in order to establish settlements and Islamic teaching centres around water wells, and many of these centres were later transformed into villages, towns, and cities. For example, Hargeisa

3 was established by Sheikh Madar, who lived in 1825–1918. The city of Baardheere

4 was established in the form of an Islamic

Jamaaca and a teaching location of Islam by Sheikh Ibrahim Xassan Yabarow in 1819. Jigjiga

5 and many other towns in the Somali region of Ethiopia were also established as Islamic teaching centres and have lately been transformed into cities (

Luling 2002;

Abdullahi 2011, pp. 49–73). In brief, urban life can be critical spatial, economic, and psychological contributors to national stability, harmony, and reconciliation. Urban centres can be where civilisations are conceived, knowledge can flourish, and human skills and abilities can be developed. The streets and neighbourhoods of urban areas can be sites where concepts such as democracy, fairness, justice, respect, tolerance, capacity, celebration for cultural diversity, arts, daily interactions, and communication competencies are nurtured and developed (

Bollens 2006).

Thirdly, it was reported that some parts of the Somalia coast in the south, including Mogadishu, were conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate (685–705) to secure taxation, teach Islam, to safeguard the Caliphate, and, at the same time, to assure the loyalty of these cities on the coast of Somalia to the Umayyad administration. Furthermore, migrants from Persia settled in the coastal cities of south Somalia, such as Mogadishu and the Benadir region (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 3). Other historical evidence notes that, from 1400 AD onward, masses of people living in Somalia converted to Islam (

Holzer 2010, p. 23).

In northern Somalia, known currently as Somaliland, the presence of Arabs was insignificant despite its geographical proximity to the Arabian Peninsula. Early Arab writers often described two northern coastal cities, Seila and Berbera, as non-Arab cities that were populated by black people. Arabs’ lack of interest in the north could be attributed to the fact that there were few urban centres and limited viable economic resources that could possibly attract Arab Muslim migrants (

Mukhtar 1995, pp. 7–8).

In his travels in East Africa in the 14th century, Ibn Battuta visited Zeila in Northern Somalia (currently known Somaliland), describing it as a Shiite town (

Njoku 2013). As a result of geographical proximity, the Shiite group mentioned by Ibn Battuta could be Zaydis, who mainly inhabited Northern Yemen. The Zaydi doctrine is close to that of the Sunnis when compared to other Shiite branches. The city of Zeila gradually lost its Shiite character during the period between 1623 and 1639 (

Haghnavaz 2014).

As discussed above, early sources confirm the presence of southern Arabians alongside the Somali coastal areas. However, little is known about the spread of Islam in the countryside and rural areas despite the centrality of Islam in the life of Somalis (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 2). Some reports indicate that Islam spread inland through commercial networks linked to ports in the coastal cities. The other factor is that Islamic culture is primarily urban, and where there was no urban life, Islam could not penetrate quickly (

Mukhtar 1995, pp. 4–10).

Since its arrival in Somalia, Islam has been an influential factor in the lives of Somalis. For example, Mogadishu was known by Arab historians as

daar al-Islam (a city of Islam). Because Islam emerged in the Arabian Peninsula, the impact of Arabs on Somalis has also been, and is still, obvious (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 6). Experts in Somalia’s history report that the spread of Islam in Somalia resulted in the establishment of Islamic authorities that governed Somalia until the arrival of colonial powers in the late 18th century. Like many other African societies, European colonialists divided ethnic Somalis. The North became a British protectorate in 1887; the South was colonised by Italy in 1889; Djibouti was colonised by the French; and two other parts (the current Somali region of Ethiopia and the Northern Frontier District: NFD) were added to Ethiopia and Kenya. These different colonialists created different cultures and social systems within ethnic Somalis (

Svedjemo 2002;

BBC 2017). The north and the south became independent in 1960 from Britain and Italy, forming a united Somali republic (

BBC 2017). Interestingly, Somalia and Cameroon are the only two African countries that reunited upon gaining independence, as they were previously under different colonial powers (

Cabo 2015).

Somali history shows that foreign threats and colonialism often united Somali clan divisions under the banner of Islam (

Holzer 2010;

Elmi 2010a). Indeed, Somalis felt that they owed much to Islamic teachings, they trusted in the power of God and his Prophets without any doubts, and they supported any leader who called for an Islamic state (

Lewis 1981). Thus, at various times in the past, Islam has been a rallying point for Somalis against any external domination. In the sixteenth century, many Somali clans joined the army of Ahmed Gurey, a Muslim leader in the Horn of Africa who fought against the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia. Similarly, Somalis responded to the calls from their Islamic leader, Sayid Muhammad Abdallah Hassan—who belonged to Salihiyya, a branch of the Ahmadiya Sufi Order in Somalia—in his battles against the colonial powers. Sheikh Axmad Xaaji Mahdi, who Italian officials considered the most well-known propagandist against Italian colonials in the area of the middle Shabelle region, was also a member of the Qaadiriyya Sufi Order in Somalia. He refused the Italians’ humiliating policies and urged different Somali clans in the middle Shabelle region to resist Italian colonialism. Likewise, many other religious leaders, such as Sheikh Cabdi Abiikar and Sheikh Xassan Barsane who were influenced by the Ahmadiyya Sufi Order and who died in prison, fought against Italian colonialism (

Abdullahi 2011, pp. 60–67;

Hoehne 2015;

Cassanelli 1982). Teachers and scholars of the Islamic religion also participated in the founding of the successful but now-defunct Somali Youth League (SYL), whose objectives and vision were based on Islamic teachings, and who politically fought against colonialism (

Cassanelli 1982;

Abdullahi 2011).

More recently, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and nationalists have also mobilised Somalis to fight the Ethiopian invasion in 2016. Similarly, many Somali clans have joined the ICU in order to establish an Islamic state and oust the warlords who misused, manipulated, and politically divided Somali clans and who ruled the country for more than fifteen years. These warlords were accused of being funded and used by external enemies (

Omar 2011). As discussed above, Sufi scholars led the fight against colonialism and greatly influenced the psyches and spirituality of Somali society. The section below discusses this matter alongside the role of Islam in sharing Somali identity.

4. Sufism, Spirituality, and Islamic Identity

It is believed that a form of Sufism

6 has been practiced in the Muslim world since early Islamic history. However, it is estimated that the most organised Sufi Orders emerged in the eleventh century and onwards as a reaction to materialism and the luxurious lifestyles that prevailed in the Islamic urban centres when Muslims became powerful and wealthy (

Abdullahi 2021, pp. 83–84;

Hansen et al. 2022).

Locally, the arrival of Sufi Orders in Somalia has been recorded since the early fifteenth century. However, “the renewal and reform of Sufi Orders as an organised movement were noted since the mid-nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century” (

Abdullahi 2021, p. 83).

Abdullahi (

2021) confirms that Sufi reformation led to shifting Somali religious culture from individual activities to more organised and institutionalised activities. Sufi Orders have integrated into the local customs and have taken mainly peaceful approaches. Thus, the Sufi groups dominated religious life and identity in Somali society, reaching out to the wider society, and therefore, most Somalis identified with one of the Sufi Orders (

Hansen et al. 2022;

Abdullahi 2021, pp. 83–84). Additionally, Sufi scholars established Islamic centres. Sufism and Sufi activities were debilitated and weakened by the emergence of new Islamist movements in Somalia in the 1960s (

Abdullahi 2021, p. 84). However, Sufism was transformed during the confrontation with the Wahabi school of thought and, in particular, with al-Shabaab. Ahlu al-Sunna wa al-Jama has become “a symbol of Sufi militancy to encounter al-Shabaab” (

Abdullahi 2021, p. 84). Now, a new generation of well-educated Sufi groups has emerged and started educational institutions, such as Imam al-Shafi University, numerous schools, and many community Qur’anic schools and mosques (

Abdullahi 2021, p. 84;

Hansen et al. 2022, p. 10). Today, the Somali Sufis have reached far into the rural nomadic population and the countryside in general (

Hansen et al. 2022, p. 10).

Alongside Sufis, Somalis have adopted the ash-

Shafi’iyah school of jurisprudence, which is one of the four major Sunni schools of thought. The other three are: al-Hanafiyah, al-Malikiyah, and al-Hanbaliyah. Later in Islamic history, Abu Hamed al-Ghazali (1058–1111) was a scholar who succeeded in combining Sufism and Islamic jurisprudence. Therefore, in the Somali context, Islamic jurisprudence scholars and Sufis have integrated and lived together (

Abdullahi 2021;

Hansen et al. 2022).

There are two main

Dariiqooyin (Sufi Orders) in Somalia, which are the Qadiriyya and Ahmadiyya, and each has its local offshoots. As mentioned above, Sufism puts a lot of emphasis on spirituality and on the inward search for God. Sufism also shuns materialism and rigid legalism (

Hansen et al. 2022). In brief, spiritual resources can facilitate the practice of religious peacebuilding in protracted conflict and wars, such as those in Somalia. Faith-inspired peacebuilders can exercise compassion, care, honesty, love, patience, and humility in choosing to reach out and connect with those who represent the face of threat and harm in the midst of conflict (

Lederach 2015). The following paragraph highlights the role of Islamic spirituality in Somalis’ psyche and in their social and emotional wellbeing, with special emphasis on the role of Sufi Orders.

Dariiqooyin (Sufi Orders) were the main social, psychological, and emotional healers as well as spiritual masters in Somalia. The dariiqooyin (Sufism) in Somalia were “an extension of the similar phenomenon in the Muslim world with the added Somali specificity and flavour” (

Abdullahi 2017, p. 65). Somali Dariiqooyin (Sufi Orders) established

jamaacooyin7, focused on spiritual purification and communal chanting under the guidance of their spiritual Islamic masters in ways close to the local culture and lifestyle. Jamaacooyin have contributed to emotional and psychological wellbeing as well as the spiritual healing of huge gatherings and individuals (

Abdullahi 2017;

Harvard Divinity School 2022). Dariiqooyin methodologies of spiritual healing included

tafakur (contemplation and remembrance of Allah) either individually or collectively,

thikri (chanting with

Qasaa’id, which are religious poems) in artistic manners relevant to the local context and

qisas (storytelling), and

nabi-amaan, teaching characteristics of the Prophet Mohamed during the commemoration of his birth, known as

Mawliid (

Luling 2002;

Abdullahi 2011, pp. 49–50). Furthermore, Sufi Orders used to organise annual events through which they would bring together pastoral populations at locations of their ancestral tombs where Islamic programmes were organised, souls were healed and purified, conflicts were resolved, and religious functions were provided (

Luling 2002;

Abdullahi 2011). They followed a set of sequenced steps of religious play, such as bowing, swaying, and arm swinging, accompanied by rhythmic beats using wooden cymbals and special drums, which were some of the special aspects practiced in Somalia (

Luling 2002, p. 225). Other spiritual aspects practiced in Somalia included communal gatherings to honour people going to

Hajj (pilgrimage) in Mecca and asking them to pray and remember those left behind while in Mecca or welcoming those who have recently returned from Hajj and asking for their blessing and prayers (

Luling 2002, p. 222).

Wardi, in which verses from the Qur’an and selected

duas (prayers) from the teachings of the Prophet are mostly read silently, is also another form of highly regarded spiritual practice in Somalia (

Luling 2002, p. 228).

However, the Sufi Orders’ approach to Islam and their spiritualism have recently been challenged by the teachings of as-

Sahwa Islamiyah (Islamic awakening movements). Since the collapse of Somalia’s central government in 1991, the as-

Sahwa Islamiyah and reformist Islamic groups and their institutions played a crucial role in social services as a substitute to the collapsed central government. The Sahwa also filled the vacuum in almost all sectors and aspects of life (

Elmi 2010b;

Saggiomo 2011). Over time, these various Islamic movements developed their own educational, business, health, and charitable organisations as well as political approaches influenced by their interpretations and understanding of Islam (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 54;

Hansen et al. 2022), which brought contradicting outcomes. Although they have, to some extent, contributed to building the nation, they have also brought new challenges, leading to clashes between the traditionalist religious groups and revivalists, particularly Salafist groups. The traditional Islamic approach represented by the

fuqahaa (teachers of Islamic jurisprudence) of the Shafi’i school of thought and Sufi Orders were confronted by revivalist movements, particularly by the more recently imported ones, such as the Wahabi doctrine from Saudi Arabia since the 1980s, and then by the new Jihadi movements, particularly al-Shabaab and, to a lesser extent, the Muslim brotherhood influenced by the Egyptian Muslim brotherhood. Since Somalis are virtually all Muslims, the arising question is: How far can the Islamic religion contribute to shaping Somali identity, and can Islamic identity strengthen social harmony and stability?

Identity is a fundamental human need that, if not fulfilled, can drag individuals into conflict. People need recognition, acknowledgement and respect of their identity and belonging (

Tint 2017). The role of identity as an asset for peacebuilding and development has already been recognised by international bodies, such as UNESCO and the African Union (

Kagwanja and Hagg 2007).

Islam and clan lineages are considered to be the two major contributors to Somali identity at both the individual and collective levels (

Lewis 1981). Islam seems to be an inclusive identity maker in contrast to the exclusionary clan identity. Individuals and groups that have developed a clan-based identity seem to be unable to imagine an alternative communal identity distinct from their clannish views. Clannism is, therefore, a major form in which the contemporary, fragmented Somalis’ ‘imagined political identity’ is constructed (

Griffiths 2002, p. 37). From the Islamic perspective, the positive use of lineage identity is held with high esteem. However, the undesirable use of a clan-based identity that Islam warns to avoid is a common practice in Somali society, particularly at the political level (

Hansen et al. 2022, p. 21).

Notwithstanding, the socially fragmented nature of the Somali people’s historical experiences has mainly been caused by clan divisions or by greedy elites who exploited and instrumentalised these clan divisions. Islam, on the other hand, seems to offer Somalis a unifying force and a sense of positive belonging (

Cassanelli 1982;

Kagwanja and Hagg 2007), particularly when they are in a new culture and society that is predominantly non-Muslim, such as in Western countries (

Langellier 2010;

Holzer 2010). It is unimaginable that the term ‘Somali’ conceives any meaning without implying an Islamic identity (

Elmi 2010a, p. 50).

Religious leaders and Islamic teachers have not historically represented any particular clan, but they have been integrated into communities regardless of whether these communities were from their own clans or not. Therefore, they have been regarded as neutral while clan leaders and warrior men represented their clans (

Luling 2002;

Lewis 1981). For example,

Sufi Orders and

fuqahaa (teachers of Islamic jurisprudence) established mixed

jamaacooyin from different clans. The jamaacooyin are influenced by the philosophy of Prophet Mohamed’s teachings and practices, whereby he interconnected between

ansar (the local community of Medina) and

muhajirin (migrants from Mecca). The latter group were hosted and welcomed by the former group and finally formed a single

ummah, whose commitment to the Islamic ummah and Islamic values prevailed over tribal belonging and, at times, replaced clan identity (

Elmi 2010a;

Mukhtar 1995;

Abdullahi 2017). Similar to Prophet Mohamed’s practices, the Somali Sufis and religious leaders in general successfully created a new pan-clan community whose allegiance was only to their Islamic leader and not to clans (

Luling 2002;

Abdullahi 2011, p. 67). In fact, some early Somali preachers of Islam advised some warlike clans to leave their pre-Islamic clan affiliations and to instead adopt the wider Islamic identity (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 14). The concept of ummah and Prophet Mohamed’s practices of interconnecting between

ansar and

muhajirin have continued over the centuries and are still influential in defining and redefining the lives of Somali society, particularly within as-S

ahwa al-Islamiya (the Islamic awakening movements).

The historical recognition of religious leaders’ and the Islamic movements’ ability to stay and rise above clan rivalries has continuity to this day.

Hansen et al. (

2022, p. 21) argued that religious movements and networks have had greater success in transcending clan loyalty and clan divisions than other social movements across Somali society.

Elmi (

2010b) also contests that Somali Islamists have limited the impact of tribalism. Similarly, some new Western researchers in Somali studies have observed the phenomenon of Somali Islamists’ rise above clan divisions and hostilities in contrast to non-Islamists, who are marred into clan rivalries, disputes, and divisions. For example,

Felbab-Brown (

2018), a senior researcher from U.S. Brookings Institute, talked about her observations of Islamic revivalist groups’ capacity, such as the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and al-Shabaab, to rise above tribalism, saying “I have asked my Somali friends and interlocutors for many years, every time a single question: ‘Why is it that only ICU and al-Shabaab manage to rise above clan politics which so debilitate the functionality of the governments!’ Which so debilitate the Somali parliament?”

Despite the fact that Islam is a unifying factor together the existence of the resources for peacebuilding in Islam, these resources are not as effective as anticipated. In fact, Somalia is still one of the most war-affected and least developed countries in the world. I argue that there are several factors limiting the effectiveness of constructive Islamic resources for peacebuilding in Somalia, including the inherited colonial governance system, self-serving elites, and misinterpretation of Islam by the extremist groups.

The Somali society has suffered and endured a corrupt political elite inherited from the colonial system. Islam has constructively shaped Somalis’ identity, culture, and

xeer (the traditional clan customary law), and the subsequent governance systems existed before the arrival of the colonials. Islam has peacefully integrated into local culture and values. However, colonials brought their own governance system, designed to serve colonial interests rather than those of the Somalis (

Abdullahi 2020;

Hussein 2018). The new system marginalised indigenous knowledge, values, and familiar traditional governing mechanisms that had been shaped positively by Islam. The postcolonial government was a mere continuation of the colonial system but performed by corrupt Somali elites trained by colonials. As a result, these self-serving Somali leaders have failed. That system was replaced by a communist system imported by the military regime of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The communist regime denied traditional values and the indigenous mechanisms of governance. Similar to its predecessor, the communist system collapsed after 21 years of ruling the country with an iron fist. As a result of the failure of the two above-explained governing systems, which were in conflict with the indigenous values and systems, the corrupt elites resorted to exploiting the clan system in ways that served elite interests. Therefore, I argue that the corrupt political elite produced and influenced by the colonial system is one of the major factors perpetuating violent conflict in Somalia (

Abdullahi 2020;

Hussein 2018).

More recently, the wrong interpretation of Islam adopted by jihadist extremists to achieve their political agenda has contributed to sustaining the conflict. The extremists’ interpretation of Islam is not a home-grown approach, but it has been imported from different cultural contexts, such as Saudi Arabia. Similar to the system inherited from colonials, the imported version of interpretation was in direct conflict with the locally integrated traditional and peaceful version of Islam, such as that held by the Sufis and

fuqahaa (Islamic jurisprudents) (

Abdullahi 2020). Regarding development, neither the colonial powers nor the subsequent governments developed natural Somali resources or human capital. As a consequence, illiteracy is very high, and young people, representing 75% of the population, are vulnerable to being recruited by extremists and other criminal syndicates such as pirates, warlords, and drug dealers.

On the other hand, despite the fact that Islam has offered Somalis a unifying identity that is above clan divides, there have been elements of identity crises attributed to the Arabisation accompanied with the spread of Islam. Since the Prophet Mohamed was an Arab originating from the Qurayshi tribe, the Qur’an, the prophet’s teachings, and Islamic knowledge were in Arabic. The Arabs were associated with prestige, power, status, and glorious achievements in early Islamic history, and many Somali tribes identified with Arab ancestries, particularly with the Qurayshi tribe of the Prophet Mohamed, departing with their own indigenous clan belongings (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 14). For that reason, many Somalis are still experiencing an identity dilemma, such as the question of whether they are Arabs or Africans.

Douglas Jardine, however, believed that Somalis’ physical and facial features exhibit evidence of their long-standing relations with Arabs, and, therefore, Somalis are an amalgamated society, resulting from intermarriage between Arab traders and visitors and local Africans (cited in

Abdi 1993, pp. 22–23). Whether the claim of descent from Arabs is true or not, the reality is that Somalis are linked to and greatly influenced by Arabs through Islam, proximity, cultural communication, and trade. The Somali language contains a considerable number of Arabic words, and Arabic is a natural second language for Somalis (

Lewis 1980).

Another weakness associated with Arabisation is that most Islamic Awakening movements and their educational institutions adopt quite extreme interpretations of Islam regarding cultural identity, and they discourage many aspects of Somali cultural practices, including traditional folklore, songs, plays, etc., because they believe that these cultural aspects are incompatible with Islamic teachings (

Omar 2011). For example, a prominent Sheikh who is the chairman of one of the main Islamic organisations in Somalia recently warned against a music concert that was planned to be performed by a prominent female singer, Kiin Jaama, on Friday 20 April 2018 in Mogadishu. He argued that such music is dangerous and a threat to religious orders and the morals of Somali society, urging Somali people not to attend this show (

Hiiraan 2018b). This is in contrast to the traditionalist Sufi Orders, who successfully utilised and still use different forms of art, such as Islamic songs, storytelling,

nasro (specific religious chanting with drums using locally made instruments) for preaching Islam, social healing, and reconciliation. Alongside spiritual practices and strengthening the identity of Somali society, Islam has equally introduced the oral Somali society to an unfamiliar, new form of education based on reading and writing through learning Islam in the Arabic language. The following explores this matter.

5. Islamic Education

Historical facts show that Islam introduced Somalis to an unprecedented educational system contingent on reading and writing in the process of learning Islam. Evidence suggests that education is the most important instrument for building peace in conflict-affected societies (

Pherali and Lewis 2011;

Smith 2010). Education engages and transforms minds, and as wisdom says that ‘war begins in the mind’, by the same analogy, peace must begin in the mind (

Kagwanja and Hagg 2007). Emotional and psychosocial injuries, social and economic development, the building of human capital, and the construction of national stability can also be addressed and improved through education (

Pherali and Lewis 2011;

Smith 2010). In the following, I discuss the role of Islamic education in peace, stability and development in Somalia’s history as well as continuity and change in Islamic practices over time.

The first verses of the Quran revealed, indicated the importance of learning through reading skills and writing by pen that will enable people to know something human beings do not know. As the Quran says “Read: In the Name of your Lord who created… He who taught by the pen. Taught man what he never knew” (Chapter 96 verses 1-5). Because of the Islamic encouragement for learning, a ‘bottom-up educational revolution’ was started by Islamic organisations after the collapse of the Somalia’s central government in 1991 and “the education sector soon became the biggest employer of the nation” (

Abdullahi 2017, p. 103). Islam provided the first formal educational curriculum for Somalis (

Hoehne 2015). Centuries ago, Ibn Battuta

8 (1369) reported that:

Somali sultanates and centres in Mogadishu city and Benadir region placed a great importance on education. Students from faraway places were provided lodging and food similar to what was provided at student hostels such as the Riwaqs of al-Azhar and Porticos of Damascus, Baghdad, Medina and Mecca. Ibn Battuta himself was lodged in the students’ dorm in Mogadishu.

Before the modern education system was introduced by colonial powers, traditional education in Somalia, known as

dugsi or

mala’mat (Qur’anic school), was a community-centred form of Islamic education administered by local people. These traditional Islamic schools and teachings provided basic education to the masses and contributed to reducing

jahli (ignorance). After students graduated from dugsi/mala’mat by mastering the ‘reading and writing skills’ of the Qur’an in the Arabic language, they joined

xer-cilmi (knowledge-seeking seminarians), where higher levels of study of diverse subjects of Islam and Arabic language and literature were undertaken. For Somali nomads, this type of higher education took place under the shades of

geed-xereed (knowledge-seeking seminarians’ trees), whereas in cities, it took place in

masaajid (mosques) and

mowlac (small and invisible prayer sites spread in the suburbs). Describing the travel of knowledge-seeking seminarians studying at traditional Islamic higher education and their integration with the locals,

Andrzejewski (

2011, p. 28) explains that:

A teacher of law [Islamic jurisprudence]…traditional Islamic higher education… and theology… in the Somali territories… often had an itinerant school which depended for its upkeep on the generosity and hospitality of nomadic pastoralists, and it had to move across long distances, especially in hard times, in order not to outstay its welcome. Bonds of friendship often developed between the teachers and their hosts which in turn might lead to intermarriage, while the itinerant students themselves sometimes travelled even greater distances than the teachers as they sought out the most famous sheikhs in distant centres of learning.

Interestingly, many people who did not receive opportunities to learn through dugsi/mala’mat and, therefore, did not learn how to read and write Arabic used to attend geed-xereed, or masaajid and mowlac sessions, to learn through listening to explanations of Islamic subjects. These people earned the reputation of

ilmi-dhegood9. Until recently, the traditional Islamic education systems explained above were practically open to all men regardless of age. However, over the last few decades, they have been open to both men and women regardless of their ages. Before modern education, titles such as

Culumo or Sheikhs (Islamic scholars) and

macallin (Qur’anic teachers) were the only titles known and recognised by Somalis as designated educated people. Because these traditional learning methods were and still are community-centred education systems, they remained resilient, continuous, and sustainable for centuries, and they have been functional to this day, even during the diaspora, particularly with duigsi/mala’mat (

Luling 2002;

Abdullahi 2011, pp. 46–48). (see

Figure 2).

Although traditional Islamic education is seminally important, it lacked the ability to respond to changing practical social services and the need to touch their everyday life. It also lacked the capacity to transform Somali society by producing skilled, productive, and creative people, simply because traditional Islamic education was largely based on memorisation, and rote-learning. The impact of traditional Islamic education on stability and peace was not on a level in which it could have pacified warring tribes; otherwise, a 100% Muslim society would not have had continuous violent conflicts for centuries.

One of the earliest formal Islamic NGOs in Somalia was the Somali Islamic League (SIL) established in 1952. Its objectives and teachings included the promotion of Shari’a law and Arabic language through its Islamic education schools. SIL Islamic schools were funded by Egypt (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 54). Recently, since the collapse of the Somalia socialist government in 1991, Islamic organisations have contributed greatly to the reconstruction of the country’s education system and have become a de facto substitute for the ministry of education. They have also proven to be reasonably effective in the management of their schools, colleges, and universities (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 54). Groups close to the Muslim Brotherhood, such as al-Islah and their affiliates, took the lead in the education sector (

Hoehne 2015;

Hansen et al. 2022), promoting the brotherhood’s philosophies together with nationalist sentiments. For example, before the 2007 displacement caused by the Ethiopian invasion, Islamic organisations that were mostly associated with brotherhood philosophies had 13,000 students in their schools in Mogadishu, and the number has increased remarkably since. Additionally, most universities such as Mogadishu University were established by intellectuals inspired by their Islamic faith (

Conciliation Resource 2010). The effort of local Islamic organisations to respond to educational needs have partially been supported by international Islamic charities managed by Somali diasporic members. These international Islamic NGOs have also focused on education and humanitarian support (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 54).

The educational initiatives undertaken by Islamic awakening groups have created environments conducive to positive socialization and have shifted mindsets from war to normality, fostering the idea of positive interaction and a sense of dialogue through a culture of pen, paper, and learning instead of guns. However, I believe that the impact and relevance of Islamic education to Somalia’s context is questionable. This is because the curricula and subjects taught at these educational institutions were mainly imported from other countries, particularly from Arabs, and may not address the needs of a conflict-affected Somali society, such as citizenship, social participation, promoting peace, gender issues, reconciliation, viable dialogue, tolerance, and respect of diversity. To contribute to peacebuilding, stability, and recovery processes, Islamic education should address drivers of violence in religious sentiments, promote dialogue and social healing, recognise diverse identities, and facilitate inclusive participation of its members in all aspects of life (

Pherali and Lewis 2011;

Smith 2010).

A well-designed educational curriculum in conflict-affected societies can prevent violence by helping people understand symptoms and warning signs of violence or underlying causes of violent conflicts and the best ways to respond to this violence in non-violent ways (

Pherali and Lewis 2011;

Smith 2010, p. 2). However, that does not seem to be the case in Somalia’s education system, including Islamic education.

On the other hand, instead of strengthening peace and social harmony, education can be an active driver of violent conflict and a tool for radicalisation by perpetuating inequalities, teaching contentious readings of history and events, fueling grievances, and deepening stereotypes, xenophobia, and other antagonisms or biased knowledge that favours some groups over others or the othering of social groups (

Pherali and Lewis 2011;

Smith 2010). I argue that Islamic education in Somalia may, to some extent, widen social divisions even within Islamist groups. I attribute such divisions not to Islam itself, but to the interpretation of Islam by some extremist groups to achieve their end goals and political agendas. Such a political and an interest-based interpretation or misconception of religion itself can happen to any religion. To harmonise society and resolve social conflicts, Islam provides Somalis with new religious-based mechanisms of conflict settlement, reconciliation, justice, and good governance, although its contribution to politics is controversial. Some may ask about the effectiveness of these mechanisms, at least at the political level. The following section elaborates on these issues.

5.1. Musaalaha (Reconciliation), Justice, Governance, and Political Islam

5.1.1. Musaalaha (Reconciliation)

Islamic teachings have immensely influenced the reconciliation mechanisms of Somali society. Islamic teachings promote “salaam” (peace) and conflict resolution through (a)

Sulh10, which means a conflict settlement (or ending violent behaviour, e.g., cease-fire); (b)

Islāh, which means conflict transformation (or treatment of the root causes of the conflict); and finally (c)

Musaalaha, which means reconciliation (or treatment of the psychological and social effects of the conflict) (

Aroua 2013, p. 78). These Islamic practices (Sulh, Islaah, and Musaalaha) are drawn from the Islamic Shari’a law and have, to some extent, been applied by Somalis who integrated these Islamic peace values and concepts into

xeer (the Somali traditional customary laws) to come up with a single workable method that deals with social conflicts (

Le Sage 2005, p. 5). Early callers for Islam in Somalia encouraged warriors and warring Somali clans to adopt the Islamic philosophy of Sulhi and to embrace “peace which is an Islamic ideal, and settle their disputes in an Islamic way” (

Mukhtar 1995, p. 14).

Therefore, it is not surprising that Somalis seek help with unresolved disputes from the

ulamaa (Islamic scholars). Ulamaa have played, and are still playing, a critical role in conflict settlement and reconciliation meetings, either inside or outside Somalia. They can influence public opinion during weekly Friday sermons or through circulating their prerecorded lectures on social media (

Hansen et al. 2022). They are also the main group that offers private and public counseling sessions for conflicting parties and their representatives during negotiations. The ulamaa also speak to the general population through the media, urging them to show flexibility, justice, love, respect, empathy, mercy, care, collaboration, and a sense of unity. To some extent, Somali ulamaa practically put their lives on the firing line to stop war. For instance, when Aydeed and Ali Mahdi militias started exchanging heavy gunfire in 1991–1992, scholars such as Sheikh Mohammed Moallim, Sheikh Ibrahim Suuley, and Sheikh Sharif Sharafow started to traverse the frontlines in the midst of crossfire in a symbolic effort to urge a ceasefire. Another example is

al-Islax, which is one the largest contemporary Islamic organisations in Somalia. Islax established a peace council named ‘Somali Reconciliation Council’ (SRC), whose primary focus was on reconciliation between warring parties. For example, in the early 1990s, SRC “sent out mobile peace caravan missions” in an attempt to negotiate local peace deals in rural locations. Given their experience in peacemaking, religious leaders are likely to prove to be valuable allies for any actor seeking to engage in these issues (

Hansen et al. 2022, p. 14).

Despite the historical reputation and respect for the ulamaa, the reality is that the current political manifestation through violent actions and attitudes of jihadist and radicalised groups have undermined the traditional moral authority of the

ulemaa and, in the longer term, may have caused serious damage to the reputation of Islamist agendas and missions (

Conciliation Resource 2010). On the other hand, justice is a major Islamic principle that is rooted deeply in the traditional Somali justice system. The section below discusses the influence of Islamic justice in Somalis’ traditional justice system together with Islamic governance, which, in many ways, has governed the Somali people since Somalis embraced Islam.

5.1.2. Justice and Governance

Justice is one of the main Islamic principles, and it nurtures both inner and outer peace, instills a sense of fairness and equality, promotes social trust, and keeps security and social harmony. Justice and good governance are necessary to build and attain sustainable peace and social confidence in systems. Justice, good governance, and sustainable peace are inherently linked and mutually reinforcing of each other (

Zuin 2008).

In the early Islamisation of Somalia, some successful sultanates emerged in different parts of the Horn of Africa, currently known as Somalia. For example, Somalia’s historical city of Seila was famous as the capital city of the Sultanate of Ifat until 1415, and then Seila was inherited by the Adal Sultanate. There was also a powerful Ajuran Emirate in southern Somalia (

Abdullahi 2011, p. 45). Similarly,

Mukhtar’s (

1995, p. 11) research on Somali history confirms the existence of several ancient towns and markets along the coastline of Somalia established after the arrival of Islam. Therefore, I believe that these Islamic Sultanates, Emirates, towns, and markets developed their own justice, governing systems, and rule of law drawn from Islamic teachings and Islamic civilisation. This is in line with Ibn Battuta’s report, who centuries ago (1304–1369) observed:

The tremendous development of Islamic judicial systems… in the Somali sultanates of the Benadir coast where a judiciary council sat weekly to hear the complaints of the public. Questions of religious law are decided by the Qadi (judge); others are judged by the council… this has always been the custom among these people

This is also in agreement with

Luling’s (

2002) findings, who argued that there was a combination of religious and political leadership in the Sultanates of Geledi, Mogadishu, Baraawe, and Merka, where Sultans used to be religious or

ulamaa (religious scholars), which necessitates governance according Shari’a law. Currently,

Saggiomo (

2011) and

Hansen et al. (

2022) found that Islamic NGOs in Somalia have been less corrupt. They have acted as a source of institutional stability in Somalia, and they have also shown effective management, good services, reasonable ethical governance, and an organisational ethos influenced by Islamic principles, all of which positively impact peace, recovery, and nation building. In brief, good governance and the rule of law are the foundations for peace, stability, and successful urbanisation.

In Somalia’s context, there are three main forms of governing justice systems:

Shari’a law,

Xeer (traditional customary governing law), and the formal secular justice system (

Zuin 2008). The Xeer and Shari’a laws had historically coexisted and were shaped from each other. Xeer in particular was heavily influenced by Shari’a, and its implementation has been reinforced by Islamic morality, including forgiveness and reconciling community divides for the sake of Allah, hoping for Allah’s reward in both this life and the hereafter if justice is delivered properly, and fearing Allah’s punishment if justice is not delivered

11 (

Adam et al. 2004;

Hoehne 2015;

National Security Consultant 2014;

Abdi 1993).

Abdullahi (

2011, p. 24) explained that, although Islamic Shari’a has greatly influenced Xeer principles and practices, the full application of Islamic Shari’a has never been practiced across Somalia. This means that there are no coherent local memories and historical legacies of Islamic rule and governance in Somalia’s context.

By definition,

Shari’a is a comprehensive justice system that Somalis commonly recognise as legitimate and just in comparison to the formal and secular justice that resonates more with the international community (

Le Sage 2005, p. 8;

Zuin 2008). Additionally, the abuse of the formal secular justice system by Somali governments has led to Somalis being suspicious of the formal secular justice system. The formal justice system is perceived by the Somali mainstream as corrupt, ineffective, and biased in favour of the elites.

Felbab-Brown (

2018), whose research was based on fieldwork studies in Somalia in 2017, endorsed the view that the formal justice system is controlled by the most powerful groups who are not in touch with the community. Felbab-Brown argues that “None trust the judiciary courts that both are dominated by particular clans but are also extraordinarily corrupt”. Therefore, the formal and secular justice system lacks legitimacy in the eyes of the wider population (

Zuin 2008). The formal justice system can thus be seen to perpetuate Somalia’s conflict rather than solve its problems.

Because of the justice it delivers, a sense of sacredness, and the legitimacy it has historically enjoyed from the perspective of Somalis, the Shari’a justice system and Islamic courts have been and still are seen as more trustworthy than the formal justice system. For that reason, al-Shabaab’s Islamic courts are seen as effective and more trusted by the Somali population.

Felbab-Brown (

2018) recounts:

…al-Shabaab… delivers justice that is not corrupt, maybe harsh but nonetheless swift, and predictable…there are repeated stories including those I heard from my fieldwork of police officers who work in Mogadishu going to al-Shabaab controlled areas…they [police officers] go to [al-Shabaab’s] Mogadishu courts for dispute resolution; these [who go to al-Shabaab’s Mogadishu courts] are police officers. None trust the judiciary courts that…are…extraordinarily corrupt. Women often prefer to have…property disputes resolved by al-Shabaab. This despite the fact al-Shabaab brutalizes women…but in terms of property dispute because of the Shari’a ruling side that often is far better than [formal] justice courts or than clan courts (Xeer) that women do not have any representation; they [women] cannot address clan elders.

Because of this trust in Shari’a justice, Islamic courts have in the past been invested, funded, and sustained by Somali people. Additionally, people in bush and rural areas have access to Shari’a and Xeer compared with the formal judiciary system, which exists only in big cities (

Le Sage 2005;

Zuin 2008). Shari’a law and Xeer systems have already been in place for centuries, and they have been owned, used, and accepted by Somali people. This has proven to be sustainable compared with the formal justice system.

Although significant reform and improvements of Shari’a and Xeer are required in the long term, it can be argued that no major new and immediate structural changes are needed. Furthermore,

Xeer-Beegti (experts in traditional customary law) and

Qudaad (Islamic judges) are available and ready to perform the job, although further training and upgrading programmes are required. This is because the version of Shari’a law used in Somalia was written hundreds of years ago and has not been updated since. The same thing can be said of Xeer, a traditional customary law that is informal and under-developed, having been an unwritten agreement transmitted through oral narrations since pre-Islamic times (

Zuin 2008;

Adam et al. 2004).

5.1.3. Political Islam

As discussed earlier, in Somalia, there were multiple political Islamic representations by numerous Islamic Sultanates and Emirates in the period between the 12th and the 19th century, including Ifat and Adal in the north and later Ajuuraan in the south, and Shari’a law was assumed to be their governing mechanisms. However, contemporary studies have shown that apolitical

12 Sufism has historically dominated Somalia’s religious practices. In the mid twentieth century, the new Islamic awakening and reformist movements that had emerged across the Muslim world reached Somalia. These new reforms advocated for a return to the original sources of Islam. It is in this context that the modern term of ‘political Islam’ gained popularity, reputation, momentum, and relevance. Political Islam is comprehensive, as it reforms all aspects of society. A common goal that all political Islamists have is to establish Islamic states, but their strategies on how to establish an Islamic state are greatly different (

Elmi 2010b;

Hoehne 2015;

International Crisis Group 2005).

In the Somalia context, contemporary political Islam is dominated by non-Sufis, and it started as an underground movement in the mid 1970s when General Bare’s scientific socialistic regime clashed with Islamic scholars and executed 10 of them who had publicly opposed Bare’s socialist policies. Moderate or well-balanced contemporary Islamic awakening groups were inspired by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood of political action through students who travelled to Egypt and, lately, to Sudan to study, and then, when they returned to Somalia, they started to spread the philosophies of the Muslim Brotherhood. The well-balanced groups’ vision is to influence the future of the Somali state and its political system in the long term using a Western-developed democratic system, referencing Islamic philosophies (

Holzer 2010, p. 24;

International Crisis Group 2005). In contrast, the more strict Salafist groups were inspired by the Wahabi school of thought mainly through migrants and students who studied in Saudi Arabia’s Medina University (

Holzer 2010, p. 24). However, Islamists’ real influence on Somalia’s national politics was, in general, perceived as rather weak until the emergence of the Islamic Court Union (ICU) in 2006 and the subsequent government led by Sharif Sheikh Ahmed.

Historically, Islamist politicians in Somalia have been the strongest when they have been in opposition to non-Muslim foreign threats, such as Ahmed Gurey’s fight in the sixteenth century against Ethiopia’s Orthodox-dominated Kingdom, fights against colonialism, and the more recent fight against the Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006 and, to some extent, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) (

Holzer 2010, p. 24;

Hoehne 2015).

Since the start of Somalia’s civil war, affiliates with Egypt’s Muslim brotherhood have adopted peaceful political activities. Additionally, the Salafist groups, particularly the now-defunct al-Itihaad (currently known I’tisam) and salafiyah jadiidah (new salafists), which were influenced by the Saudi Wahabism school of thought, have lately appeared to change their approach and sought political transformation without using violence (

Saggiomo 2011;

Elmi 2010b;

Hansen et al. 2022). This may be because the Salafists were defeated on many fronts, including Arare and Bosaso by militia clans when they fought against clan warlords such as Mohamed Farah Aydiid and Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed. They were also defeated in the Gedo region (

Saggiomo 2011;

Hansen et al. 2022). On the other hand, Sufi groups such as Ahlu Sunna wal Jama’a have, until recently, remained without any noticeable change. Their political activities, however, resumed around 1991, as the powerful warlord Mohamed Farah Aydiid claimed himself to be a ‘traditionalist’ and a good partner of Sufis.

Recently, Somali Sufis held a two-day international conference in Mogadishu in April 2018 that focused on the fight against extremism and terrorist activities as well as on the peaceful spreading of Islam. The delegates were drawn from Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, the UK, Algeria, Morocco, Turkey, Sudan, Nigeria, Iraq, Senegal, and many other countries (

Hiiraan 2018a). This conference was partly aimed at countering al-Shabaab, Daesh, and Wahabism in general, and, as an outcome, the strengthening rather than the waning of religious influence can be expected in Somalia in the years and decades to come.

Similar to Somalia’s political divisions caused by social fragmentation and civil war, Somalia’s Islamist groups are politically diverse and characterised more by competition, division, exclusion and contradiction based on their different interpretations of Islam. These schisms are hardly less severe than those that plagued the tribalist political factions (

International Crisis Group 2005;

Elmi 2010b). Although fragmented armed militia clans emerged to fight the oppressive military regime, most Islamic organisations started operating at the grassroots level and worked hard towards strengthening their grassroots organisational base without developing collaborative mechanisms among them (

International Crisis Group 2005). Despite the above-explained challenges and divisions facing political Islam in Somalia, the current role of religious actors in the political process is considerable and will be a formidable part of the political landscape in the foreseeable future (

Hansen et al. 2022).

Thus far, this paper has discussed the continuity and modifications of Islamic services and teachings in the past and present, with special emphasis on the fields of education, spirituality, identity, justice, governance, and politics. The following section highlights some contemporary Islamic services by which as-Sahwa Islamiyyah has had tremendous contributions towards humanitarian action, charity, and economics.

6. Humanitarianism and the Economy

Since the collapse of Somalia’s central government in 1991, Islamic organisations have emerged as major local humanitarian groups. Although many humanitarian organisations focus on saving lives and making a smooth transition from relief to recovery, they have recently started to link their work with other areas more proactively, particularly with development, in order to contribute to the sustainable peace and processes of recovery. This means that humanitarian activities can potentially enhance, strengthen, and reinforce long-term peacebuilding outcomes (

Rossier 2011).

Islamic charities and Islamic humanitarian NGOs in Somalia can be run informally through mosques and groups or can be formally managed by Islamic movement organisations or their associates. Either informal or formal, these Islamic groups and organisations carry out voluntary aid work on the bases of their Islamic values (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 54). Many of these charities are funded by Muslim-majority countries, particularly the Gulf States, including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and the Emirates, or by International Islamic organisations based in the West, such as the UK, France, USA, and Canada. Additionally, there are local charity NGOs which are funded by local Somalis or by the International Islamic NGOs they are affiliated with. The main financial resources for Islamic organisations include

zakaat (alms), funds given by Muslim countries or privately owned companies, as well as public

sadaqaat (public voluntary donations) from individuals or Islamic philanthropists. Giving these donations is a sign of piety and religious practice (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 54). As time passes, many of these international and Gulf-based Islamic organisations are becoming indigenised and integrated into local Islamic charities. However, these indigenised organisations remain connected to their original headquarters outside Somalia for fundraising reasons and for ideological attachment (

Saggiomo 2011).

In terms of economy, over the last few decades, Islamic-value-inspired organisations and groups have greatly contributed to economic development and business in Somalia. Economic growth can reduce the likelihood of civil war, as it creates a lot of opportunities. To be part of the solution and recovery process, economic development policies in conflict-affected countries must be designed in ways that strengthen peace and stability (

International Alert 2015).

Since the collapse of Somalia’s central government in 1991, Islamic ethics such as trust have played a salient role in reshaping the economy of Somalia. This is because they have created consumer trust in business people through the projection of a trustworthy image (

Hansen et al. 2022, p. 21). Additionally, Islamic organisations associated with as-

Sahwah Islamiyya (Islamic awakening movement) received generous funding early in the civil war from their international counterpart charities, particularly those in the Gulf countries. At some point, they used these funds for their own enterprise businesses. The success of Islamist businesses can be attributed to the Islamic values and the positive side of tribal affiliations, which are instanced in businesses run by these Islamists in Somalia (

Holzer 2010).

The majority of new enterprises have emerged since the collapse of Somalia’s military regime, such as that of import/export trade, telecommunications, and money transfer, which are now owned by people inspired by Islamic awakening movements. In contrast, traditionalist Islamic groups in Somalia, such as the Sufis, had historically very limited involvement in business and trade (

Conciliation Resource 2010). Unlike the traditionalist religious groups, the new Islamic Somali charity organisations established by the Islamic revivalist and reformist movements do invest economically and promote the creation of private social service enterprises, which have created a lot of employment opportunities and which directly contribute to stability. For example:

A capable and qualified Individual such as a medical doctor is located by the charity organisation that wishes to invest financial resources in the start up of a medical social service. The charity then pays for the necessary infrastructure, the equipment and the initial salary of the newly hired professional, who in turn starts ‘the business’ by charging fees to his patients. This continues until he reaches the point of being financially independent… At this point, the charity withdraws and the cycle continues.

The result is that the Islamic reformist charities stimulate the founding of new social services in a business manner, which financially become sustainable on their own, and they are potentially able to implement pro-poor initiatives that are naturally in line with Islamic principles. As a humanitarian side effect, poor individuals may, in fact, be exempted from paying the service fee (

Saggiomo 2011, p. 57). As a result of social trust and integrity in Islamic-based trade, Islamist businesses attract a lot of shareholders from different tribes that enable them operate across divided communities (

Conciliation Resource 2010).