Muslim-Jewish Harmony: A Politically-Contingent Reality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- That one’s religious identity is wholly exclusive, whereas this can differ in specific circumstances, especially in cases of forced conversions, inter-religious marriage, or communicatio in sacris—all of which were common in medieval Islamic Iberia.

- (ii)

- That one’s religious association is the primary, most important, and most distinguishable identity marker for an individual—which stands above ethnicity, nationality, tribal association, social class, and other perceivable markers.

- (iii)

- That a binary analysis is possible on its own terms—i.e., one does not need to contextualise further, for example, if Christian interplay was fundamentally significant to the Muslim-Jewish relationship (e.g., in Islamic Iberia), then to what extent is the analysis truly binary?

2. Islamic Iberia

2.1. Samuel ibn Naghrela—A Functional Political Reality

2.2. Joseph ibn Naghrela—Political Disintegration

- ‘Do not consider it a breach of faith to kill them, the breach of faith would be to let them carry on.

- They have violated our covenant with them, so how can you be held guilty against the violators?’

3. Continuation of Political Contingency Post-1948—The Modern Day

3.1. Deadlock—The Military Regime

3.2. The Sahwa—A Religio-Political Rise

4. The Abraham Accords—Present Developments

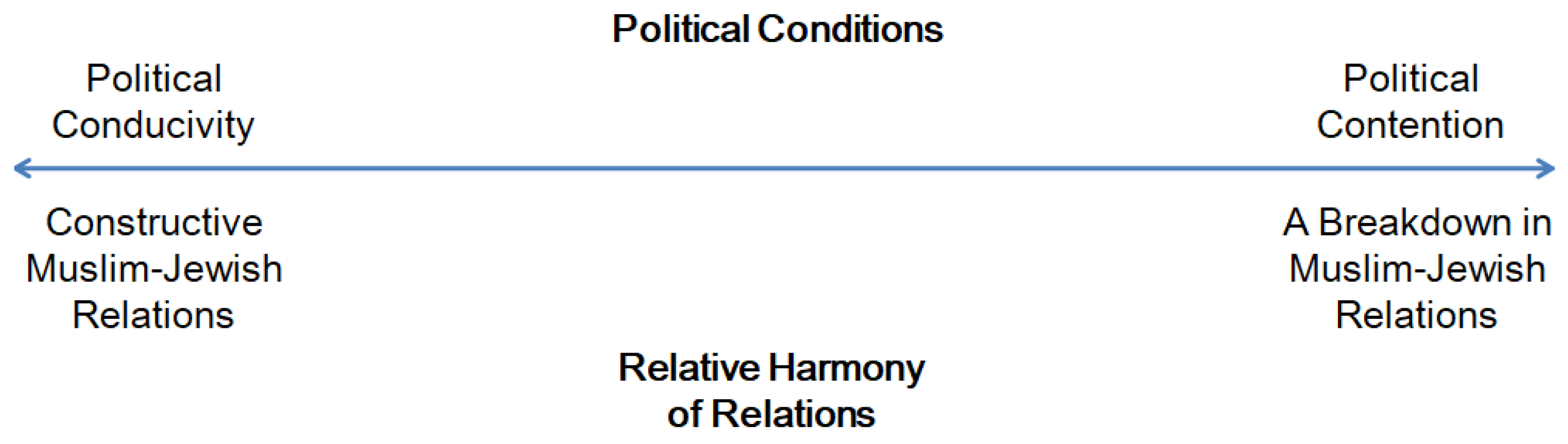

5. Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aburish, Said. 1998. Arafat, From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 41–90. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Atawneh, Muhammad, and Nohad Ali. 2018. Islam in Israel: Muslim Communities in Non-Muslim States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 18–19, 90–95, 130–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Nohad. 2004. Political Islam in an Ethnic Jewish State: Its Historical Evolution, Contemporary Challenges and Future Prospects. Holy Land Studies 3: 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Komi, Ahmed. 2018. Gaza’s Christians blocked from travel to Bethlehem. Al-Monitor, December 24. [Google Scholar]

- Arab Opinion Index. 2020. Section 6, Nov. The 2019–2020 Arab Opinion Index: Main Results in Brief. See Figure 36 (and Figure 35 for Further Information). Available online: arabcenterdc.org (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Bennison, Amira, and Maria Gallego. 2007. Jewish Trading in Fes on The Eve of the Almohad Conquest. Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Hebreo 56: 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Boms, Nir Tuvia, and Hussein Aboubakr. 2022. Pan Arabism 2.0? The Struggle for a New Paradigm in the Middle East. Religions 13: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Americo. 2020. Introduction. In The Spaniards: An Introduction to their History. Translated by William King, and Selma Margaretten. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. i–xii. First published in 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Hillel. 2009. Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917–1948. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark. 1991. The Neo-Lachrymose Conception of Jewish-Arab History. Tikkun 6: 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Constable, Olivia Remie, ed. 1997. Medieval Iberia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cudworth, Erika, Timothy Hall, and McGovern John. 2007. The Modern State: Theories and Ideologies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Nissim. 2003. The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status. Sussex: Sussex Academic Press, pp. 200–1. [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, Abdallah Nimr. 2001. Al-Ḥall al-Muqtara wa al-Salām al-Manshūd. In al-Mithāq, 8th ed. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Daud, Abraham. 1971. Sefer ha-Kabbalah of Ravad. Jerusalem: Seder Olam Rabba, pp. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dumper, Michael. 1994. Islam and Israel: Muslim Religious Endowments and the Jewish State. Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Eban, Abba. 1984. Heritage: Civilization and the Jews. New York: Simon & Schuster, pp. 144–46. [Google Scholar]

- Freas, Erik. 2012. Hajj Amin Al-Husayni and the Haram al-Sharif: A Pan-Islamic or Palestinian Nationalist Cause. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 39: 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freih, Abu Freih. 2014. Islam in the Negev: Conflict and Agreement between the ꜤUrf and the SharīꜤa in the Muslim Arab Population in the Negev. Master’s thesis, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er Sheva, Israel; pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Ian. 2012. Dialogue between Christians, Jews and Muslims. Ph.D. thesis, MCD University of Divinity, Melbourne, Australia; pp. 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, Jonathan, and Roie Yellinek. 2021. UAE-Israel diplomatic normalization: A response to a turbulent Middle East region. Comparative Strategy 40: 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCC JewishUAE. 2020. Video-Link. The Video Has Been Downloaded in Case of Its Removal from YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AuOJMtHYKK0 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Kramer, Martin. 1986. Islam Assembled: The Advent of the Muslim Congresses. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–9, 123–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1984. The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Rose. 1971. The Myth of Arab Toleration. Midstream 16: 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Jacob Rader. 1938. Jew in the Medieval World: A Source Book, 315–1791. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, pp. 335–38. [Google Scholar]

- Menocal, Maria Rosa. 2002. A Grand Vizier, A Grand City. In The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. New York: Brown and Company, pp. 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Religious Affairs. 1962. A Plan for Training Qāḍī Candidates. Ministry of Religious Affairs (Government Paper), October 28, 20/29 (II). [Google Scholar]

- Prager, Dennis, and Joseph Telushkin. 1983. Why the Jews? The Reason for Anti-Semitism. New York: Simon & Schuster, pp. 110–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rekhess, Elie. 1989. Israeli Arabs and the Arabs of the West Bank and Gaza: Political Affinity and National Solidarity. Asian and African Studies 23: 119–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmer, Tilde. 2010. The Islamic Movement in the Jewish State. In Political Islam: Context versus Ideology. Edited by Khaled Hroub. London: Saqi, pp. 182–209. [Google Scholar]

- Rouhana, Nadim. 1997. Palestinian Citizens in an Ethnic Jewish State: Identities in Conflict. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 96–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Peled, Alisa. 2001. Debating Islam in the Jewish State: The Development of Policy toward Islamic Institution in Israel. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 121–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, Solomon. 1902. Genizah Material. Jewish Quarterly Review 6: 643. [Google Scholar]

- Spivakovsky, Erika. 1971. The Jewish presence in Granada. Journal of Medieval History 2: 215–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, Norman. 1979. The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, pp. 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, Merlin. 1970. The Position of Jews in Arab Lands following the Rise of Islam. The Muslim World 60: 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibi, Bassam. 1981. Arab Nationalism: A Critical Enquiry. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 165–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tritton, Arnold. 1930. The Caliphs and Their Non-Muslim Subjects. Bombay: Oxford University Press, pp. 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera-Molins, Maria. 2010. Al-Andalus and the Maghrib (from the fifth/eleventh century to the fall of the Almoravids). In The Western Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries. Edited by Maribel Fierro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, M.I. Muslim-Jewish Harmony: A Politically-Contingent Reality. Religions 2022, 13, 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060535

Ahmed MI. Muslim-Jewish Harmony: A Politically-Contingent Reality. Religions. 2022; 13(6):535. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060535

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Mohammed Ibraheem. 2022. "Muslim-Jewish Harmony: A Politically-Contingent Reality" Religions 13, no. 6: 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060535

APA StyleAhmed, M. I. (2022). Muslim-Jewish Harmony: A Politically-Contingent Reality. Religions, 13(6), 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060535