The Saint Dionysius and Saint Margaret Altarpiece from the Cathedral of València

Abstract

1. Location and Origin of the Altarpiece

2. Description of the Altarpiece

3. Central Board

4. The Lateral Boards

4.1. Adoration of the Magi

4.2. The Ascension of Jesus

E de continent los sants apòstols partiren del cenacle qui és en lo mont de Sion e anaren-se’n en Betània axí com lo senyor los avia manat. E anà-y axí mateix la Gloriosa ab alcuns feels creents. [And suddenly the holy Apostles left the cenacle, which is on Mount Zion, and went to Bethany, as the Lord had told them to do. And the Virgin Mary also went with them, with some believers].(VCE 10,18 p. 351v,a)

Lavors lo gloriós Senyor primerament se posà sobre una bella pedra plana qui encara es aquí segons diu Sulspicius e diu que les sues santes petgades hi són impresses (…). Segonament diu aquest tantost la sua gloriosa cara rajà e ensenyà les dots de glòria. (…) Ell se levà pujant dret en alt envers lo cel e pujant levà les mans en alt faent gràcies al seu Pare e en senyal de gran amor baxà la cara envers ells e benehí-los altra vegada (…) estant en alt digueren-los axí: Barons de Galilea! Guardats alt al cel sapiats que Jesus, Fill de Déu, qui ara se’n puja ab tanta virtut e potestat davant vosaltres, axí vendrà poderosament e gran al juhí final a la fi del món. E los dits àngels dients aquestes paraules una nuu resplandent se entreposà entre lo Salvador pujant e los apòstols e aquells que aquí eren e ja no·l veeren pus pujant [Then the Lord stood on a beautiful flat stone which is still there according to Sulpicius, and it is said that his footprints are still marked upon it (…). Secondly it is said that his glorious face exploded in light and it showed the features of glory. (…) He arose towards Heaven and also raised his hands as a sign of gratitude to his Father, and as a sign of great love, lowered his face towards them and he blessed them once more. (…) and as he was rising to Heaven the angels said: Men of Galilee! Look at Heaven and be aware that Jesus, the Son of God, who in this moment is rising to Heaven with so much virtue and power in front of you, will come again with great power at the Last Judgement and at the end of the world. And as soon as the angels finished these words, a dazzling cloud appeared between the Lord and the Apostles and the rest of the people who were there at that moment, and they could not see the Lord anymore].(VCE 10,19 p. 352,a)

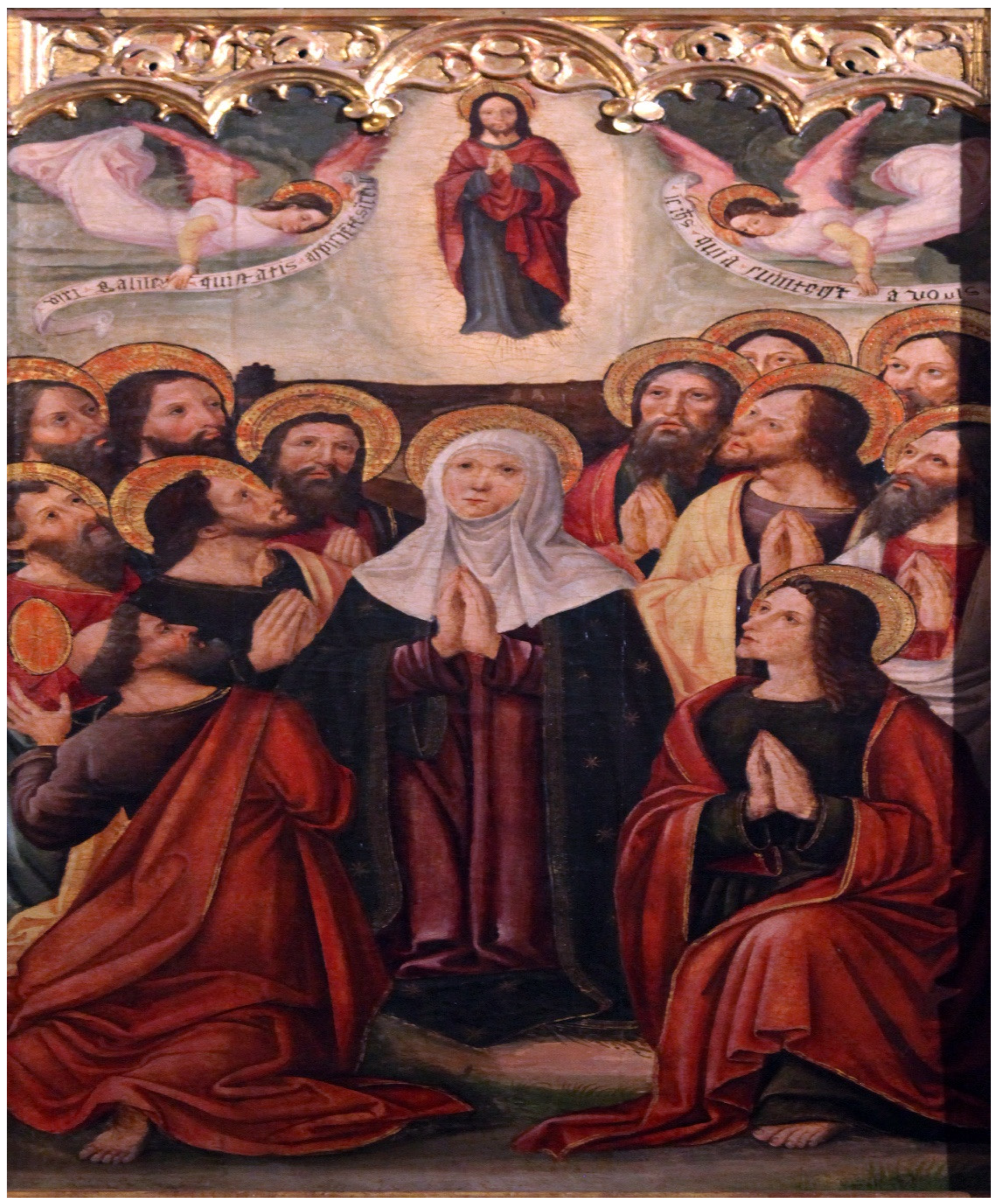

4.3. Pentecost

Pujat, donchs, lo Salvador, en lo cel imperi, alt sobre tots los altres cels, e pus bell e pus virtuós, los sants apòstols romangueren en lo cenacle de Jesucrist en lo mont de Sion, en Jerusalem. E aquí, per deu jorns orants e dejunants, e apparellant-se a reebre lo Sant Sperit lo jorn de cinquagèsima qui era lo cinquanté dia aprés la Resurreció, segons que posa sent Luch Actuum, primo. E com la gloriosa Mare de Déu, ab altres, fos en lo dit cenacle, e fossen entre tots cent e vint, lo Sant Sperit vench sobre ells e la manera posada per lo dit sent Luch e glosada per los sants doctors estech aquesta. Primerament, lo dit jorn de cinquagesima a hora de tèrcia estech fet gran tro en l’ayre e soptosament aparegueren cent e vint formes de lengües en semblances de foch e posaren-se sobre les dites cent e vint persones, cascuna sobre lo seu. E tantost foren tots plens del sant Sperit. [The Savior arrived at the upper Heaven, which is the most beautiful and virtuous one, high above all others, and at the same time the Apostles remained in Jesus Christ’s cenacle, on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. And they prayed and fasted for ten days, and were ready to receive the Holy Spirit on the fiftieth day after the Resurrection, according to the word of St. Luke Actuum, primo. And as the Holy Mother of Christ was in that cenacle and there were one hundred and twenty people among them, the Holy Spirit came to them in the manner that St. Luke explains and that has been glossed by the holy Doctors of the Church. So that day at the terce hour a great thunder in the air was heard, and suddenly one hundred and twenty tongues with the form of fire appeared, and they were set over these one hundred and twenty people. And thus they were full of the Holy Spirit].(VCE 10,54 p. 354,a)

4.4. The Assumption of the Mother of God

Lo segon punt en aquesta materia lo qual posa Teofilus si és que lo fill beneyt li tramés lo àngel que la saludà molt delitablement e li presentà aprés la salutació un ram de palma luent dient-li que lo seu preciós Fill lo li trametia en senyal que ella havia triumfat e ahuda victòria de totes les sues temptacions. E per tal volia que lo dit ram fos portat davant lo lit on ella seria posada quant seria portada a soterrar. [The second point regarding this matter according to Teophilus is that the blessed son of the Virgin sent her an angel who greeted her very kindly and afterwards gave her a bright palm branch and told her that sending her the palm branch was a sign that she had overcome all her temptations. And therefore, he wanted this palm branch to be carried to the bed where she would be placed when she was taken to be buried].(VCE 10,35 p. 359v,a)

E nota ací aquest doctor que com lo dit àngel li apparech denunciant-li que aprés tres dies finaria ses dies, que en senyal de la victòria de la carn e dels altres enemichs que avia vençuts en sa vida que lo seu gloriós Fill li trametria del cel un bell ram de palma luent lo qual no era fet en terra mas solament era creat en lo cel per la virtut de Déu tot poderós lo qual ram de palma lo gloriós fill seu manava que li fos portat davant lo lit com seria portada a la sepultura. [And this doctor remarks that when this aforementioned angel appeared and announced to her that she would die within three days, as a sign of victory over the flesh and other enemies that she had defeated during her life, her glorious son would carry her a bright palm branch that had not been made on Earth, but had been created in Heaven by the virtue of God Almighty. And her glorious son ordered this palm branch to be taken to the bed on which she would be carried for the burial].(VCE 10,38 p. 360v,a)

Lavors los sants apòstols tots agenollats li besaren los peus ab gran reverència e prengueren lo lit e portaren lo molt reverent e sagrat cors a la vaill de Josafat on li faeren fer lo sepulcre. E sent Pere portà al cap del lit e cantant intonà lo psalm qui comença In exitu Israel de Egipto e sent Johan per manament de sant Pere portà-li davant lo ram de la palma damunt dit, axí com lo Senyor avia manat fins al dit loch. [And then the holy Apostles knelt down and kissed her feet with great reverence and took the bed where the very holy and reverent body of the Virgin lay to the Josaphat valley, where the sepulcher was made. And St. Peter sang the psalm that begins In exitu Israel de Egipto (When the people of Israel left Egypt) as he was carrying the bed. And St. John followed the command of St. Peter and brought the aforementioned palm branch to the burial place, as the Lord had ordered].(VCE 10,43 p. 362v,a)

Los sants apòstols continuant son cant vingueren al sepulcre e ahí ab gran reverència posaren lo preciós cors de la verge gloriosa. [The Holy Apostles sang until they arrived at the sepulcher and they placed the precious body of the glorious Virgin there with great reverence].(VCE 10,43 p. 362v,b)

4.5. The First Apparition of the Resurrected Christ to His Mother

E, acostant se ja a la posada hon la dita Senyora staua, sanct Gabriel, qui era hu dels ordenadors de la professo, cuyta, ab la verga dor en la ma, per portar la bona noua a sa senyoria, de la qual era special seruidor e priuat; e, entrant dins lo retret de sa altesa, troba sa excellencia algun poch alegra, car havia vist partir de la corona del Senyor qui dauant tenia, e del seu propri mantell, la sanch quey era escampada, e creya que lo seu Fill era resuscitat; ab tot nos podia del tot alegrar, puix vist nol hauia. [And St. Gabriel came to the place where the Virgin was, with his golden cane in order to bring the good news to her, to whom he was a special servant. He also had a good acquaintance with her. And when he arrived where she was, he found her with a little joy, since she had seen that the blood had been removed from the crown of thorns and from the cape that her son wore when he was taken to be crucified. And she thought that her son had resurrected, but she could not be totally happy, since she had not seen it personally].(VCV 3, 165)

E, hoint açò Adam ab goig no recomptable, cuytà de anar. E, venint dauant la Senyora, fon recomplit de tanta alegria e consolació que li paregué hauer augmentat en gran grau la benauenturança sua, e prostrà·s als peus de sa altesa volent besar aquells ab sobirana reuerència; e la Senyora no·u permès, reuerint-lo com a pare, e, leuant-se de peus, manà-li que·s dreçàs. [And as Adam heard that with immense joy, he went towards the Virgin. And as he came to the Virgin, he was so full of joy and relief that his blessedness seemed to have grown; and he prostrated himself at the feet of the Virgin, and he wanted to kiss them with great reverence; but the Virgin did not allow it, since she revered him as a father, and she stood up, and ordered him also to stand up].(VCV 3, 174)

E, la Senyora vehent dauant si Adam e·ls fills seus ab tanta glòria e jocunditat, fon lo goig de sa senyoria infinit, car veja complit de tot son desig que del instant de la sua incarnació hauia supplicat lo eternal Pare per la reparació e glorificació de natura humana, la qual obtengué perdent la vida de aquell excel·lent Fill qui, sens comparació, molt més que la pròpria vida amaua; e per ço sa clemència estimaua molt e·s alegr[au]e de aquella redemptió com a cosa que molt li costaua. [And when the Virgin saw Adam and his sons in front of her, she was full of infinite glory and joy, since her wish was accomplished. Since the moment of the Incarnation she had requested the eternal Father to repair and glorify human nature, and it was done through the death of that excellent Son, whom she loved more than herself without comparison. And because of her leniency she praised and rejoiced over that Redemption, even though it was something that cost him dearly].(VCV 3, 176)

E dit açò, aquell gloriosíssim cors fon reunit ab la ànima guarit de totes les nafres, exceptat de les principals cinch, que per gran excel·lència hauia reservades, les quals embellien tant aquell glorificat cors e lançauen de si tanta claror e resplandor que, admirats tots los àngels e sancts qui aquí eren, e recomplits de irrecomptable goig e alegria, prostrats en terra, adorant sa Magestat, digueren: “Dignus es Domine lesu Christe accipere laudem e benedictionem et gloria et honorem.” [And afterwards, that extremely glorious body joined with his soul, and it was healed from his wounds, except for five, which had been reserved by His Excellency. And these wounds embellished so much that glorified body and threw so much light and gleam that the angels and saints that were there prostrated themselves to the ground, and full of countless joy and delight, they worshiped his Majesty and said: “Dignus es Domine lesu Christe accipere laudem et benedictionem et gloria et honorem.” (You Lord Jesus Christ are worthy of praise, and benediction, and glory, and honor)].(VCV 3, 161)

4.6. Dead Jesus Christ on the Cross

5. The Predella

E axi, aquesta Senyora, turmentada per tanta dolor, Veent dauant si aquelles persones que al seu Fill amauen tan carament, perdé lo parlar e totes les forces, e caygue esmortida; [And so the Virgin Mary, tormented with so much pain, seeing in front of her the people who loved her son so dearly, lost her speech and all her strength, and fainted].(VCV 3, 84)

Joseph e Nicodemus, ab tot tinguessen molta dolor e compassió del dolorós capteniment de aquella Senyora, hagueren a pendre esforç per executar lo que fer-li auien, e dreçaren les scales, fermant les en la creu, e ells abduix pujaren, cascú per sa escala; car lo que ells podien fer en seruici del Senyor no·u volien comanar a nengun altre. E, començant arrancar aquells dolorosos claus, sanct Joan los féu senyal que·ls y donassen amagadament, que la senyora Mare no ves de prop la feredat e granea de aquells claus que axí cruelment hauien turmentat lo seu amat Fill; e axí fon fet. E, desclauades les mans per aquells virtuosos homens, besauen-les ab molta dolor e làgrimes, no gosant cridar per no alterar la dolorosa Mare, qui tan prop li staua. E Joseph, qui era pus animós, per ésser caualler hauia la força de sa persona bé experimentada, dix a Nico[de]mus que lexàs lo braç del Senyor que tenia, que ell sol sostendria tot lo cors, e que deuallàs a desclauar los sagrats peus. E, Nicodemus dexant lo braç, Joseph abraçà aquell cors ab singular reuerència e amor, sentint tanta consolació dins la sua ànima que quasi ixqué de si mateix; e conegué ésser pus rich e mes abundós en tot bé tenint aquel Senyor que si posseýs tots los béns del món. [Even though Joseph and Nicodemus suffered much pain and compassion for the Virgin, they endeavored to do what they had to do, and they set the stairs, tightened them to the cross, and each one of them got up through his stair, since they did not want to order other people to do what they could do personally for the Lord. And when they began to pull those painful nails out, St. John requested them to deliver them to him secretly, so that the Virgin could not see how big they were, and the harm that they had inflicted on her beloved Son, and thus it was done this way. And when they pulled the nails from his hands out, they kissed his hands with lots of pain and tears, but they did not dare to shout, so as not to upset his glorious mother, who was next to them. And Joseph, who was strong and could carry the weight of the whole body, told Nicodemus to let the arm of the Lord loose, which he was holding, that he would hold the whole body, and that instead he should pull the nails out from the feet. And when Nicodemus dropped the arm, Joseph embraced that body with so much love and reverence, and feeling so much consolation in his soul, he understood that in that moment he was richer and more abundant in goods than if he had possessed all the goods on the Earth].(VCV 3, 90–91)

6. The Canopy

les celles que havia altes e pontades, el nas gran e bell, e lo front ample e la faç ampla e la boca poqua, e les dentes fort belles e blanques e la barba poqueta mas bifurcada, los ulls fort bells e queucom gracets. E.ls cabels fins als muscles, declinants a color de castanya. (…) Avia les mans longues ab fort bells dits, los braços fort responents a la sua statura, sinó que eren fort rescarpats. Lo pit ample e les espatles belles e amples. E la altea del seu cors tenia egualtat, cor ne era dels majors ne dels menors mas decantava més a granea cor era gran covinentment. (…) era vestit de dues gonelles (…) una vestedura de filadiç morat, la qual no era cosida ab agulla ans la li féu la Gloriosa mare sua ans que·l Senyor nasqués e crexia ab ell. (…) e com preycava alçava la ma dreta tenint tres dits levats en alt. [the eyebrows were high, the nose was big and beautiful, and the forehead was wide, and the face was wide but the mouth was small, and the teeth were very beautiful and white, and the beard was not very grown but split in two, the eyes were very beautiful and endearing. His hair went down to his shoulders, and was mostly brown in color. (…) He had long hands with very beautiful fingers and his arms were according to his height. His chest was wide and his shoulders beautiful and wide. And he was of average height, although a little taller than the rest of the people. (…) And he wore two shirts (…) made of violet cloth, which were not sewn with needles, but made by his mother the Virgin before he was born, and they grew with him. (…) And when he preached he raised his right hand with three fingers pointing to the sky].(VCE 8, 1; 215v,b)

7. Comprehensive Explanation of the Altarpiece

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Tormo, de primer (Arte español 1923, p. 299; Levante 1923, pp. 132–33) el va creure de Francesco Pagano i després de Paolo da San Leocadio o d’algun deixeble seu, i el va considerar ·l’obra mestra de prerafaelisme valencià” (Los Museos 1932, p. 125, nº 30). El baró de San Petrillo va interpretar erròniament els seus escuts com del llinatge Cabanyes (AEAA 1933, p. 94), i des d’aquesta falsa premissa va suposar que el pintor Antoni Cabanes a qui connectà amb aquest llinatge, podria haver sigut l’autor d’aquest retaule que suposadament hauria lliurat com a ofrena personal al temple de Sant Joan de l’Hospital, incloent-hi el seu escut. Com que aquest argument no convencia, per fantàstic, Saralegui (AAV 1933, pp. 33–34) i Post (History, VI 1935, t.II p. 396) van preferir referir-se a l’autor de retaules com a Mestres dels Cabanyes o simplement Mestre de Cabanyes, admetent, en tot cas, la presumpta identificació dels escuts feta per San Petrillo. Això donaria peu a la invenció del Mestre de Cabanyes com a mer nom de laboratori per a designar un anònim pintor, la identitat del qual avui saben que correspon a l’etapa juvenil de Vicent Macip. (Benito and Galdón 1997a, p. 52). Tormo believed at first (Arte español 1923, p. 299; Levante 1923, pp. 132–33) that the author was Francesco Pagano and later he thought that it was Paolo da San Leocadio or one of his disciples, and considered it as the masterpiece of Valencian Prerafaelism” (Los Museos 1932, p. 125, nº 30). The baron of San Petrillo mistakingly understood the shields as belonging to the Cabanyes family (AEAA 1933, p. 94), and therefore he supposed that the author was painter Antoni Cabanes, whom he connected with this family. The altarpiece could have been created as a personal offering to the Church of Sant Joan de l’Hospital. Since this argument was not convincing, Saralegui (AAV 1933, pp. 33–34) and Post (History, VI 1935, t.II p. 396) preferred to name the author as Mestres dels Cabanyes or simply Mestre de Cabanyes. They admitted in any case the identification of the shield that San Petrillo made. It would be the starting point for the invention of the name Mestre de Cabanyes as an artificial name for an anonymous painter. Nowadays, neverthless, we know that the painter’s identity corresponds to Vicent Macip in his youth. (Benito and Galdón 1997a, p. 52). |

| 2 | Vicent Macip (c. 1475–1550). His life and work have generated great controversy among scholars. He was the first in a line of painters established in Valencia over three generations. His work is influenced by Paolo da San Leocadio and Rodrigo de Osona and, later, by Sebastiano del Piombo whose work will mark a change of direction in Macip’s painting towards his stage of creative maturity for which he will be known as the person who introduced the First Renaissance to Spain. About Vicent Macip vide Martínez Aloy (1909–1910); Sanchis Sivera (1909); Tormo (1932); Garín y Ortiz de Taranco (1955); Cerveró (1966); Albi (1979); Benito (1981, 1988, 1993); Vallés and Benito (1991); Samper (2001); Benito and Galdón (1997a, 1997b); Company and Tolosa (1997, 1999a, 1999b) and Tolosa et al. (2006). |

| 3 | O, Senyora, que aquell sagell del Pare eternal, de tan gran estima, hon es esculpida la ymatge sua, ço es, lo seu diuinal Fill, del qual es dit: ymago bonitatis illius, car es ymatge propria de la bonea e excel·lència del Pare seu, a vos, Senyora, sola, lo ha comanat la Magestat del dit Pare, no fiant de neguna altra creatura de tot lo imperi seu! (VCV 3, 172) [Oh my Lady, that seal of the Eternal Father, where his image is sculpted, that is, his divine Son, of whom it is said: ymago bonitatis illius, i.e., suitable image of goodness and excellency of your Father, to you alone, Lady, has been assigned by the Father’s Majesty. And He does not rely on any other person than you, among all the ones that belong to him]. |

| 4 | The golden background of the table appears in another work of Macip: Saint Anne with the Virgin and Jesus the Infant accompanied by Mary Magdalene. Owing to this coincidence Benito and Galdón (1997a, p. 54) suggests dating this altarpiece to the first decade of the 16th century, since the work of Saint Anne is dated from 1507. |

| 5 | Ecce sacerdos magnus, qui in diebus suis placuit Deo, et inventus est iustus: et in tempore iracundiæ factus est reconciliatio. [Behold a great priest, who in his days pleased God, and was found righteous: and in the time of wrath was made a reconciliation] (Sirach 44:16–17). |

| 6 | Intret, intret in patriarcharum familiam gentium plenitudo, et benedictinem in semine Abrahæ, qua se fílii carnis abdicant, fílii promissionis accípiant. Adorent in tribus magis omnes populi universitatis Auctorem; et non in Iudæa tantum Deus, sed in toto orbe sit notus, ut ubique in Israel sit magnum nomen eius [Enter, let the fullness of the nations enter into the family of the patriarchs, and receive the blessing in the seed of Abraham, by which the children of the flesh renounce themselves, the children of the promise. All the peoples of the universe worship the Author in three ways; and let God be known not only in Judea, but in the whole world, so that his name is great everywhere in Israel]. Leo Magno, In Epiphania Domini 3, 3: PL 54, 240–44. |

| 7 | This book belongs to the medieval literary genre of the “Vitae Christi” (Lives of Jesus Christ), whose best example is Ludolf of Saxony’s “Vita Christi”. Each book that belongs to this literary genre is not just a normal biography but also a story, a comment from the Fathers of the Church, a list of moral and dogmatic considerations, instructions, meditations, and prayers. Everything is connected with the life of Jesus Christ from his birth until his Ascension. In this book, Eiximenis’s complete scholasticism can also be found in some of its parts. Only in this work the influence of heterodox sources, especially the apocryphal Gospels, can be noticed. In any case, according to Albert Hauf, the most important authors that influence this book are the Pseudo-Bonaventure and the Franciscan Ubertino of Casale. Isabel de Villena’s “Vita Christi” especially emphasized the women who played an important role in Christ’s life (e.g., his mother Marie and Marie Magdalene). Villena’s “Vita Christi” begins with the Nativity of the Virgin and ends with the Assumption of Mary. Mary’s and Elizabeth’s visitations are extended by Isabel. Mary also has dialogues with allegorical representations of diligence and mercy. This dialogue already appeared in Boethius’s “The Consolation of Philosophy.” Female figures are as important in Isabel’s book as Jesus and the corresponding male figures themselves. Isabel even defends the defamed Eve and Mary Magdalene. |

| 8 | For an overview of Assumption Apocrypha in Spanish see de Santos Otero (2003, p. 705) and Aranda (1995, p. 324). |

| 9 | The mystical mandorla, as an intersection of two circles, takes on a double meaning, since it represents the communication between two worlds and two different dimensions, i.e., the material and the spiritual world, the human and divine dimensions. Vide (Cirlot 1992, p. 295). |

| 10 | This iconographic matter is closely related to the crucifixion. Upon his birth, the Magi ask Herod for the location of the the king of the Jews and at the end of his life, the reason for his execution inscribed on the cross similarly read: This is the king of the Jews. |

| 11 | The matter of Mary as queen can be found in Micah 5:2. It deals with the model of gebiráh in the Davidic kingdom. See (de Vaux 1976, pp. 172–74). |

References

- Albi, José. 1979. Joan de Joanes y su Círculo Artístico. 3 vols. Valencia: Institución Alfonso el Magnánimo. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, Gonzalo. 1995. Dormición de la Virgen: Relatos de la tradición copta. Apócrifos cristianos 2. Madrid: Ciudad Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Fernando, and José Luis Galdón. 1997a. Vicent Macip (c. 1475–1550): Museu de Belles Arts de València, del 4 Febrer-20 Abril 1997. València: Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia—Generalitat Valenciana. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Fernando, and José Luis Galdón. 1997b. Retablo de San Dionisio y Santa Margarita. In Vicente Macip (h. 1475–1550). València: Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia—Generalitat Valenciana. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Fernando. 1981. Vicente Macip y Joan de Joanes. Semejanzas y diferencias de un estilo pictórico similar. Debats 1: 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Fernando. 1988. Sobre la influencia de Sebastiano del Piombo en España: A propósito de dos cuadros suyos en el Museo del Prado. Boletín del Museo del Prado 9: 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Fernando. 1993. El maestro de Cabanyes y Vicente Macip. Un solo artista en etapas distintas de su carrera. Archivo Español de Arte 66: 223–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cerveró, Luis. 1966. Pintores valentinos: Su cronología y documentación. Archivo de Arte Valenciano 37: 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cirlot, Juan Eduardo. 1992. Diccionario de Símbolos. Barcelona: Labor. [Google Scholar]

- Company, Ximo, and Lluïsa Tolosa. 1997. Petjades joanesques a la Safor. Reflexions sobre el codi lingüístic més important de la pintura valenciana del segle XVI. In Miscel·lània Josep Camarena. Gandia: CEIC Alfons el Vell, pp. 101–27. [Google Scholar]

- Company, Ximo, and Lluïsa Tolosa. 1999a. De pintura valenciana: Bartolomé Bermejo, Rodrigo de Osona, el Maestro de Artés, Vicente Macip y Joan de Joanes. Archivo Español de Arte 287: 268–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, Ximo, and Lluïsa Tolosa. 1999b. La obra de Vicente Macip que debe restituirse a Joan de Joanes. Archivo de Arte Valenciano 80: 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- de Santos Otero, Aurelio, ed. 2003. Los evangelios apócrifos. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [Google Scholar]

- de Vaux, Rolando. 1976. Instituciones del Antiguo Testamento. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Feuillet, André. 1966. L’heure de la femme (Jn 16,21) et l’heure de la Mère de Jésus (Jn 19,25–27). Biblica 47: 361–80. [Google Scholar]

- Garín y Ortiz de Taranco, Felipe María. 1955. Catálogo-Guía del Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes de San Carlos. Valencia: Institución Alfonso el Magnánimo. [Google Scholar]

- Llorca, Fernando. 1930. San Juan del Hospital. València: Prometeo. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Aloy, José. 1909–1910. La Casa de la Diputación. Valencia: Tipografía Doménech. [Google Scholar]

- Potterie, Ignace de la. 1993. María en el Misterio de la Alianza. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, Vicente. 2001. Documentos inéditos para la biografía de los Macip. Archivo Español de Arte 74: 163–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis Sivera, José. 1909. La Catedral de Valencia. Guía Histórica y Artística. Valencia: F. Vives Mora. [Google Scholar]

- Thurian, Max. 1962. Marie Mère du Seigneur et Figure de l’Église. Paris: Taizé. [Google Scholar]

- Tolosa, Lluïsa, Ximo Company, and Lorenzo Hernández. 2006. De nuevo sobre Joan Macip, alias Joan de Joanes (c. 1505–1510–1579). In De pintura Valenciana (1400–1600). Estudios y Documentación. Coordinated by Lorenzo Hernández Guardiola. Alicante: Instituto Alicantino de Cultura Juan Gil Albert. [Google Scholar]

- Tormo, Elías. 1932. Valencia: Los Museos. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Históricos. [Google Scholar]

- Vallés, Vicent, and Fernando Benito. 1991. Nuevas noticias de Vicente Macip y Joan de Joanes. Archivo Español de Arte 64: 353–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramón i Ferrer, L. The Saint Dionysius and Saint Margaret Altarpiece from the Cathedral of València. Religions 2023, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010077

Ramón i Ferrer L. The Saint Dionysius and Saint Margaret Altarpiece from the Cathedral of València. Religions. 2023; 14(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamón i Ferrer, Lluis. 2023. "The Saint Dionysius and Saint Margaret Altarpiece from the Cathedral of València" Religions 14, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010077

APA StyleRamón i Ferrer, L. (2023). The Saint Dionysius and Saint Margaret Altarpiece from the Cathedral of València. Religions, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010077