Chastity in Temperance’s Images

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Chastity as a Virtue Associated with Temperance

“Dare I ask for helps from my enemy Moderation, whom my son’s very excesses so often offend? Yet shudder at the thought of tackling that squalid old peasant woman. Still, whatever its source, the solace of revenge is not to be spurned. I must certainly use her, her alone, to impose the harshest punishment on that good-for-nothing, shatter his quiver and blunt his arrows, unstring his bow, and quench his torch”.

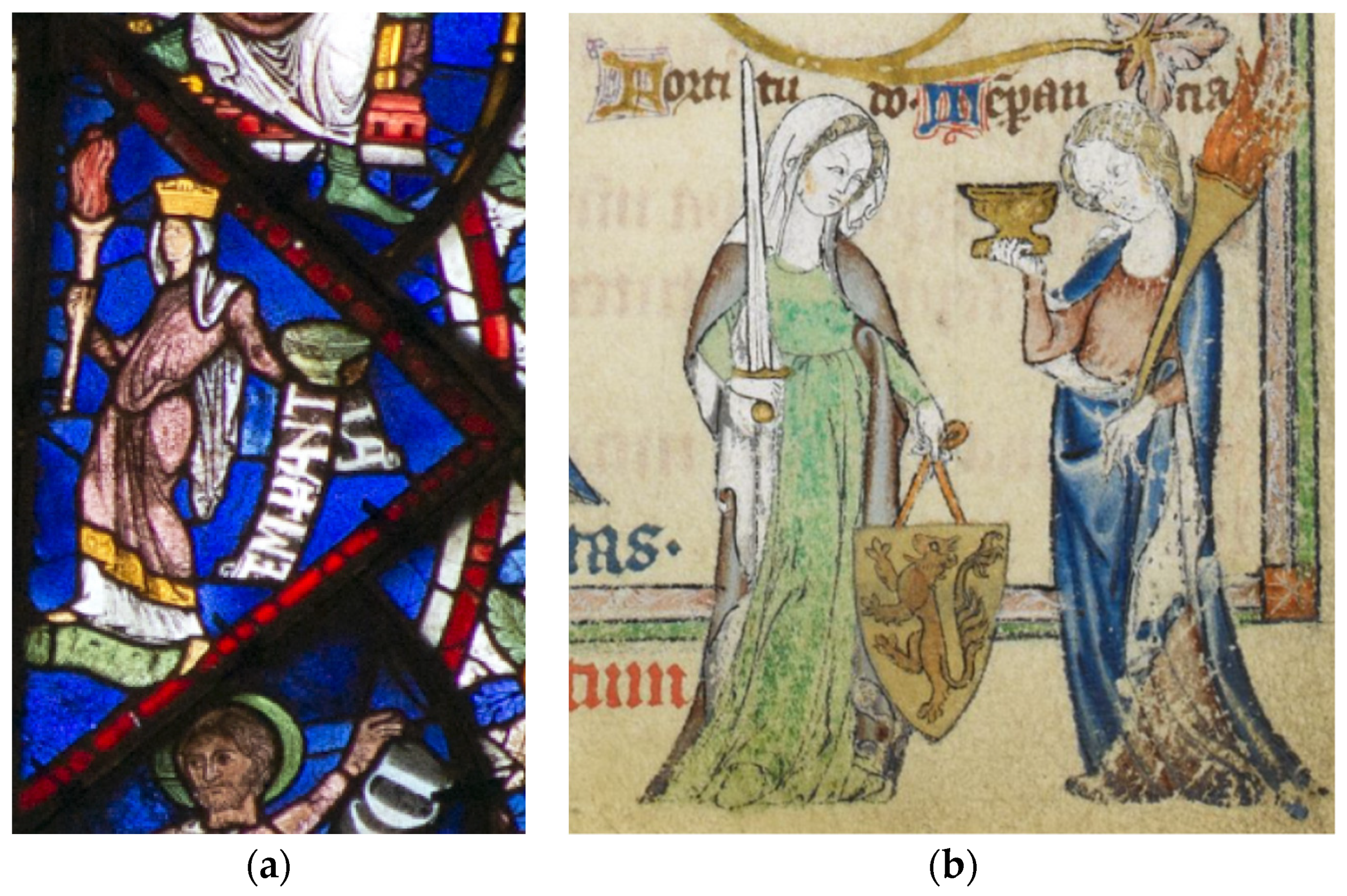

3. “Chaste Temperance” Iconographic Types

3.1. Chaste Temperance 1: Fire and Water

“Next to step forth ready to engage on the grassy field is the maiden Chastity, shining in beauteous armour. On her falls Lust the Sodomite, girt with the fire-brands of her country, and thrusts into her face a torch of pinewood blazing murkily with pitch and burning sulphur, attacking her modest eyes with the flames and seeking to cover them with the foul smoke”.

“To mediaeval mind, thoroughly familiar with such authors as Seneca and Horace, the torch appeared as a symbol of unholy ardor even more telling than the bow and he arrows—so that the illustrators of Prudentius’ Psychomachia, where only bow and arrows are mentioned as the attributes of Cupid, were prone to supplement them by the torch which in the text belongs to his mistress, Libido”.

3.2. Chaste Temperance 2: Castle and Keys

“La terza donna che’l nostro apetito/ch’ha’l soperchio dexio, domma e refrena,/sempre è d’onestà piena/e volser al suo chastel discreta chiave:/abre e serra soave,/cum vol razone a la cupiditate,/et in sobrietate/s’aviva, con fa’l corpo in nui per l’alma/e de vertù gran palma/produce e fructo bon suo dolce lito:/e poi chi vol nel sito/esser d’amore amante, chostei’l mena/a la sua real cena,/ma d’ogne vanitate e parlar brave/prima ch’i’ va, se vale./Ch’ivi è pur zente de benignitate,/sì ch’onne dignitate/a lor s’avean, però pun giù la salma/d’ogni viltà che scalma/in l’inferno Epichuro, che non volse/viver modesto e mo’ sotto lei dolse”.

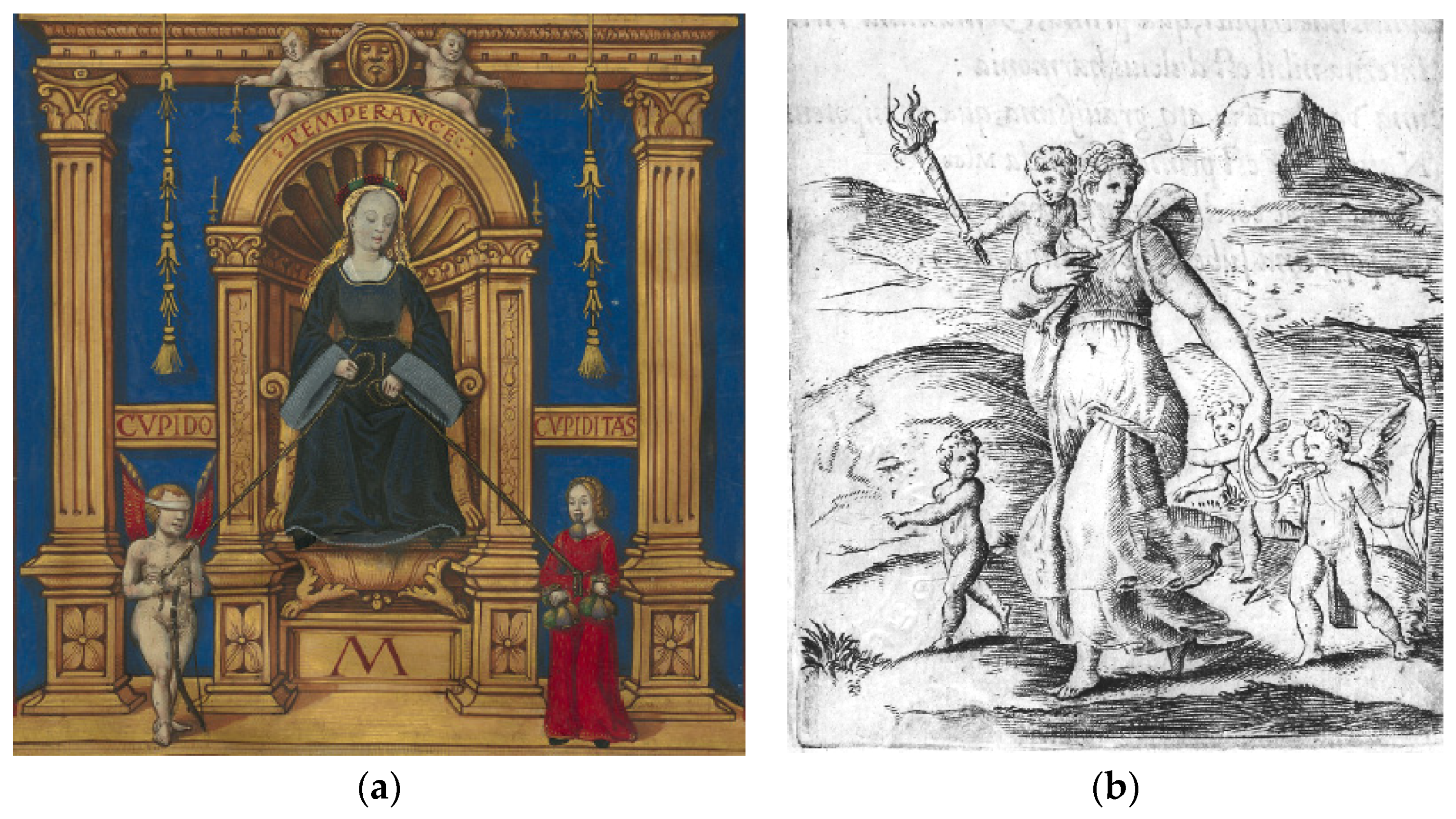

4. Attributes of Temperance Related to Chastity

4.1. Bit and Bridles

“Labraran mas vna brida/desabrida/contra el carnal mouimiento,/por que no con desatiento/en vn momento/nos manzilla fama y vida;/sy la carne no es regida y sometida/al freno déla razón, / las espuelas de afición/en tal son le dan tal arremetida,/que es muy cierta su cayda./Sera de blanca color/por honor,/que es enemiga de amores,/y serán de sus lauores/bordadores/esquiuidad y temor;/y terna mas el amargor/que el dulçor/por guardar el freno sano,/y desdeñado lo vfano,/a punto llano/labraran esta lauor,/que es mas segura y mejor”.

4.2. Salamander and Ermine

“De la salamandra, que vive de fuego, podemos conocer dos clases de hombres: una, son todos aquellos que están inflamados por el amor del Espíritu Santo, así como Nuestro Señor inflamó a los Apóstoles del Espíritu Santo, en forma de lenguas de fuego, el día de Pentecostés; (…) La otra clase, son todos aquellos que son lujuriosos y ardientes del amor carnal”.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | An iconographic type is the visual concretion of a topic. (García Mahíques 2009, p. 348). See (Montesinos Castañeda 2020). |

| 2 | From the 15th century, Virtues’ depictions were different in French art, which spread to Flemish and Spanish lands (Montesinos Castañeda 2022). |

| 3 | “Iconography”refers to an analytic description and classification of images. It is important not confusing this term with “iconology”, which refers to an analytical process to interpret visual artworks from the context in which they were created (García Mahíques 2009, p. 343). |

| 4 | Author translation. |

| 5 | See note 4 above. |

| 6 | Translation from: https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/TheGoldenAssV.php#anchor_Toc348436733 (accessed on 27 August 2023). |

| 7 | Translation from: https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/Metamorph10.php#anchor_Toc64105567 (accessed on 21 October 2023). |

| 8 | “temperantiae omnia relinquere, in quantum natura patitur, quae corporis usus requirit” (Macrobius 1952, 121; somn. 1,8,4). |

| 9 | “temperantia sequuntur modestia, verecundia, abstinentia, castitas, honestas, moderatio, parcitas, sobrietas, pudicitia” (Macrobius 1952, 121; somn. 1,8,7). |

| 10 | According to Alain de Lille Temperance’s virtues or qualities are: Continence, Chastity, Purity, Sobriety, Parsimony, Moderation, Honestity, Abstinence, Shame and Modesty (Delhaye 1963, p. 16). |

| 11 | “Ed udasi questa virtú per molte vie, ed ha catuna il suo nome per meglio averle a memoria. E quelle sono le virtú che nascono di Temperanza, e sono cosí appellate: Castità, Pudicizia, Astinenzia, Larghezza, Parcità, Umilità, Onestà, Vergogna” (Giamboni 1968, p. 9). |

| 12 | “discretio, morigeratio, taciturnitas, jejunium, sobrietas, afflictio carnis, contemptus saeculi” (Hugh of de St Víctor, De fructibus carnis et spiritus, 15; PL CLXXVI, 1003). |

| 13 | “Est autem temperantia circa delectationes tactus, quae dividuntur in duo genera. Nam quaedam ordinantur ad nutrimentum. Et in his, quantum ad cibum, est abstinentia; quantum autem ad potum, proprie sobrietas. Quaedam vero ordinantur ad vim generativam. Et in his, quantum ad delectationem principalem ipsius coitus, est castitas; quantum autem ad delectationes circumstantes, puta quae sunt in osculis, tactibus et amplexibus, attenditur pudicitia” [Other pleasures are directed to the power of procreation, and in these as regards the principal pleasure of the act itself of procreation, there is “chastity”, and as to the pleasures incidental to the act, resulting, for instance, from kissing, touching, or fondling, we have “purity”] (Aquinas 2017; S.Th. [44719] IIª-IIae, q. 143 co.). Translation from: https://www.newadvent.org/summa/3143.htm (accessed on 27 August 2023). |

| 14 | “Temperanza è la quarta virtú principale che nasce all’uomo e alla femina della buona volontà, per la quale si concia e ordina l’animo dell’uomo a rifrenare i desiderî della carne, laonde l’uomo è assalito e tentato” (Giamboni 1968, p. 9). |

| 15 | “The name of the second seed was ‘the Spirit of Temperance’. Whoever fed off this seed acquired a temperament of such a kind that he never ended up swollen, wether from over-eating or from stress. No mockery or insult could disturb his self-control; nor could an increase in his fortune, brought about by his success in trade. He would never allow himself to be upset by words thrown out in idle thoughtlessness. Nor would he ever let a suit of clothes artfully tailored and cut be seen on his back, nor spicy food from the hand of a master-chef diffuse its choice flavors on his palate” (Quoted by Tucker 2015, p. 164). |

| 16 | “Tempaerantia quippe quarta species virtutis est rationabilis in libidinem, atque in alios non rectos animi firma et moderata dominatio” (Rabano Mauro, De ecclesiastica disciplina, 3; PL CXII, 1255). “Temperantia est totius vitae modus, ne quid nimis homo vel amet, vel odio habeat, sed omnis vitae hujus varietates considerata temperet diligentia” (Halitgarius, De poenitentia 2,10; PL CV, 676). “Temperantia est dominium rationis in libidinem et in alios motus importunos” (Hildebert de Lavardin, Moralis philosophia, 36; PL CLXXI, 1034). |

| 17 | A literary image is which is composed by linguistic tools, such as a description, a metaphore or a poem (García Mahíques 2009, p. 344). |

| 18 | For more information about classical sources and Prudentius’ Psychomachia see: (Filosini 2022, pp. 9–37). |

| 19 | Other Cardinal Virtues have direct visual precedents, such as Athena/Minerva to Prudence, Heracles to Fortitude, Nemesis, Astrea, Maat or Shamash—among others—to Justice. |

| 20 | Camelliti’s paper is about Temperance’s depiction in Palazzo Minerbi-dal Sale in Ferrara (See Camelliti 2013). |

| 21 | Serafino Serafini’s Augustine of Hippo’s Triumph (ca. 1378, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Ferrara) and many 14th-century manuscripts show similar depictions. For instance: Lectura super Digesto novo de Bartoli de Sassoferrano, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, ms. 197, fol. 3r; Regia Carmina, Florencia, Bibliloteca Nazionale Centrale, Banco Rari 38, fol. 31v; Libro di Giusto, Roma, Galleria Nazionale, Gabinetto delle Stampe, inv. 2818–2833, fol. 4r. |

| 22 | Translation from: https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/phaedrus.html (accessed on 23 October 2023). |

| 23 | “Nescio cuius id est verbum sapientis iniquum,/tanquàm osurus ama. Quin ego amare velim/ut nunquam osurus. Nam quae vera, aut bona tándem/In vita reliqua est, dic mihi, amicitia?/Si quisque, olim ita amicum amet, ut fieri ipsum inimicum/posse putet? Virtusne ista rogo, an vitium est?/Quin ego non tanquàm: sed nunquam, osurus amabo./Vera sibi constat Semper amicitia” (Bocchi 1574, pp. 100–1; II, symb. XLVI). |

| 24 | “Eam non tantum non consumi igne, sed flamman etiam extinguere rigore suo” (Camerarius 1677, p. 138; IV, emb. 69). |

| 25 | “la Salamandra, che stando nelle fiamme, non si consuma, col motto Italiano, che diceva: NVTRISCO ESTIGVO, essendo propia qualità di quello animale, spargere dal corpo suo freddo humore sopra le bragie, onde avviene, ch’egli non teme la forza del fuoco, ma più tosto lo tempera e spegne” (Giovio 1559, p. 23). |

| 26 | “Della Salamandra (…) NVTRISCO ET ESTINGVO. Altri dicono c’havea scritto, Nutrisco il buono & estinguo il reo, c’havrebbe havuto altro significato” (Capaccio 1592, I, fol. 60r). |

| 27 | “E per dichiarare questo suo generoso pensiero di clemenza, figurò vn’Armellino circondato da vn riparo di letame, con vn motto di sopra, MALO MORI, QVAM FOEDARI, essendo la propia natura dell’Armellino di patir prima la norte per fame e per sete, che imbrattarsi, cercando di fuggire, di non pasar per lo brutt, per non macchiare il candore e la pulitezza della sua pretiosa pelle” (Giovio 1559, p. 31). |

References

- Amoris. 1629. Amoris divini et humani antipathia. Anvuerpiae: Snyders. [Google Scholar]

- Apuleius. 1996. La Metamorfosis o El asno de oro. Translated by Carlos García Gual. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Saint Thomas. 2017. Summa Teológica. Available online: https://www.newadvent.org/summa/3143.htm (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Aristotle. 1868–1944. Aristotle: In Twenty-Three Volumes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Aristotle. 1973. Obras. Edited by Francisco de P. Samaranch. Madrid: Aguilar. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi, Achille. 1574. Symbolicarum quaestionum, de universo genere, quas serio ludebat, libri quinque. Boloniae: Societatem Typographiae Bononiensis. [Google Scholar]

- Boissard, Jacques. 1588. Emblematum Liber. Metz: Francoforti ad Moenum. [Google Scholar]

- Cacho, María Teresa. 1999. Los moldes de Pygmalión (sobre los tratados de educación femenina en el Siglo de Oro). In Breve historia feminista de la literatura española (en lengua castellana). Edited by Iris M. Zavala. Barcelona: Anthropos, pp. 177–214. [Google Scholar]

- Camelliti, Vittoria. 2013. La Temperanza di Palazzo Minerbi-dal Sale a Ferrara. Riflessioni sulla trasmissione di una tipología iconográfica. Rivista di storia della miniatura 17: 122–36. [Google Scholar]

- Camerarius, Joachim. 1677. Symbola et emblemata. Maguncia: Christophori Küstleri. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli, Camillo. 1586. Imprese illustri di diverse. Venecia: Francesco Ziletti. [Google Scholar]

- Capaccio, Giulio Cesare. 1592. Trattato delle imprese. Nápoles: Horatij Salviani. [Google Scholar]

- de la Perrière, Guillaume. 1545. Le théatre des bons engins. Paris: Denys Ianot. [Google Scholar]

- Delhaye, Philippe. 1963. La vertu et les vertus dans les oeuvres d’Alain de Lille. Cahiers de civilisation médiévale 6: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Bartoli, Bono. 1904. La Canzone delle Virtù e delle Scienze. Bérgamo: Ed. d’Arti Grafiche. [Google Scholar]

- Faroult, Guillaume. 2006. Les Fortunes de la Vertu. Origines et évolution de l’iconographie des vestales jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. Revue de l’Art 152: 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Filosini, Stefania. 2022. Ovidian Presences in Prudentius’ Psychomachia. In After Ovid: Aspects of the Reception of Ovid in Literature and Iconography. Edited by Franca Ela Consolino. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mahíques, Rafael. 2009. Iconografiía e Iconología. Volumen 2. Cuestiones de método. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Giamboni, Bono. 1968. Il libro de’ vizî e delle virtudi e Il trattato di virtú e di vizî. Torino: G. Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Giovio, Paolo. 1559. Dell’imprese militari et amorose. Lyon: Guglielmo Roviglio. [Google Scholar]

- Horapolo. 1991. Hieroglyphica. Edited by José María González de Zárate. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Hurus, Juan or Pablo. 2013. Flor de Virtudes. Edited by A. Mateo Palacios. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial, Francisco. 1977. El dezir a las syete virtudes y otros poemas. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Lacarra, María Eugenia. 1999. Representaciones femeninas en la poesía cortesana y en la narrativa sentimental del siglo XV. In Breve historia feminista de la literatura española (en lengua castellana). Edited by Iris M. Zavala. Barcelona: Anthropos, pp. 159–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lackey, Douglas P. 2005. Giotto in Padua: A New Geography of the Human Soul. The Journal of Ethics: An International Philosophical Review 9: 563. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25115841 (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- León Coloma, Miguel Ángel. 1998. Sobre la iconografía de la templanza. Cuadernos de arte de la Universidad de Granada 29: 213–28. Available online: https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/caug/article/view/10398 (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Macrobius. 1952. Commentary on the Dream of Scipio. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, Fray Íñigo de. 1912. Vita Christi fecho por coplas por frey Yñigo de Mendoca a petiçion de la muy virtuosa señora doña Juana de Cartagena. In Cancionero castellano del siglo XV. Madrid: Bailly Bailliere. [Google Scholar]

- Moakley, Gertrude. 1966. The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family; An Iconographic and Historical Study. New York: New York Public Library. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos, José Galiano. 2019. El matrimonio medieval. Entre la castidad y la familia. Paratge 32: 119–34. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos Castañeda, María. 2020. Los fundamentos de la visualidad de la Templanza. Formación de su tipología iconográfica hasta el siglo XIV. De Medio Aevo 14: 161–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos Castañeda, María. 2022. El tipo iconográfico de la Templanza en la “nueva visualidad”. Eikón Imago 11: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Helen. 1979. From Myth to Icon: Reflections of Greek Doctrine in Literature and Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Jennifer. 1988. Studies in the Iconography of the Virtues and Vices in the Middle Ages. New York: Garland Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1965. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksells. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de Guzmán, Fernán. 1912. Coblas fechas por Fernán Pérez de Guzman de vicios i virtudes. In Cancionero castellano del siglo XV. Madrid: Bailly Bailliére, vol. 1, p. 615. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrasanta, Silvestro. 1634. De Symbolis Heroicis. Antuerpiae: Balthasaris Moreti. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1949. República. Translated by José Manuel Pabón, and Manuel Fernández-Galiano. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos. [Google Scholar]

- Prudentius, Aurelius. 1949. Prudentius, with an English Translation by H.J. Thomson. London: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Rademaker, Adriaan. 2004. Sophrosyne and the Rhetoric of Self-Restraint: Polysemy & Persuasive Use of an Ancient Greek Value Term. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, Cesare. 1765. Iconologia. Perugia: Piergiovanni Constantini, vols. 3 and 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián, Santiago. 1984. El Fisiólogo. Translated by Francisco Tejada Vizuete. Madrid: Tuero. [Google Scholar]

- Timoneda, Juan. 1992. Romance de Perseo. In Romances de la Antigüedad Clásica. Edited by M. Cruz de Castro. Madrid: Ediciones Clásicas. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Shawn. 2015. The Virtues and the Vices in the Arts. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lynn. 1969. The Iconography of “Temperantia” and the virtuousness of technology. In Action and Conviction in Early Modern Europe: Essays in Memory of E.H. Harbinson. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lynn. 1973. Tecnología medieval y cambio social. Buenos Aires: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Felicity. 1960. Oftermod et demesure. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 3: 115–17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montesinos Castañeda, M. Chastity in Temperance’s Images. Religions 2023, 14, 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111409

Montesinos Castañeda M. Chastity in Temperance’s Images. Religions. 2023; 14(11):1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111409

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontesinos Castañeda, María. 2023. "Chastity in Temperance’s Images" Religions 14, no. 11: 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111409

APA StyleMontesinos Castañeda, M. (2023). Chastity in Temperance’s Images. Religions, 14(11), 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111409