How to Protect One’s Home in Medieval China? A Study of the Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng 佛說安宅神呪經

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Research on the AZSZJ

3. A Study of the AZSZJ Based on Medieval Buddhist Catalogues

3.1. Sēngyòu’s 僧祐 Chū sānzàng jìjí 出三藏記集 (“Compilation of Notes on the Translation of the Tripiṭaka”; Liáng 梁 Dynasty, ca. 494–97)

3.2. Fǎjīng’s 法經 Zhòngjīng mùlù 眾經目錄 (“Catalogue of the Multitudes of [Buddhist] Scriptures”; Suí Dynasty, ca. 594)

3.3. Fèi Chángfáng’s 費長房 Lìdài sānbǎo jì 歷代三寶記 (“A Record of the Three Treasures through the Ages”; Suí Dynasty; 597 CE)

3.4. Dàoxuān’s 道宣 Dà-Táng nèidiǎn lù 大唐內典錄 (“Catalogue of Canonical [Buddhist] Scriptures of the Great Táng”; 664 CE)

3.5. Míng Quán’s 明佺 Dà-Zhōu kāndìng zhòngjīng mùlù 大周刊定眾經目錄 (“Catalogues of Scriptures, Authorized by the Great Zhōu”; 695 CE)

3.6. Zhìshēng’s 智昇 Kāiyuán shìjiào lù 開元釋教錄 (“Catalogue of Śā[kyamuni]’s Teachings from the Kāiyuán Period”; 730 CE)

- Fascicle 1, section “Lost translations of the Later Hàn,” with the comment: “It is also called Ānzhái zhòu fǎ, [Sēng]yòu referred to it as Ānzhái zhòu (亦云安宅呪法,祐云安宅呪; T. 55, No. 2154, p. 483c5);

- Fascicle 3, section “Lost translations of the Eastern Jìn,” with the comment: “The Ānzhái zhòu—it is already included in the ‘Lost translations’ of the Later Hàn [section]; here it is recorded again, and one should know that this is redundant” (安宅呪-後漢失譯錄中已有,此中復載,故知重也。; T. 55, No. 2154, p. 509b27);

- Fascicle 12, section “Single translations of Mahāyāna scriptures (there exists a volume/text)” (大乘經單譯(有本), with the comment: “The Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng in one fascicle, a lost translation of the Later Hàn” (《安宅神呪經》一卷 ,後漢失譯; T. 55, No. 2154, p. 603c1);

- Fascicle 19, section Dàshèng rùzàng lù 大乘入藏錄: “The Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng in one fascicle, also referred as Ānzhái zhòu jīng” (《安宅神呪經》一卷(亦云《安宅呪經》); T. 55, No. 2154, p. 687c23).

4. An Annotated Translation of the “Canonical” Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng

At that time, the World-Honored One knew [the minds of the Licchavi sons] and therefore asked, “All of you sons of the elders! Why do you have this troubled appearance, [you seem to be] miserable and unhappy, and there is despair in your expressions?”

At that time, the sons of the elders14 univocally addressed the Buddha: “World-Honored One! We wonder when people reside in the world, are there frequently auspicious and inauspicious events concerning the homes of their families?” The Buddha answered: “All these matters are created based on the mental activities and dream-like thoughts (i.e., illusions) of the sentient beings; but it is not the case that [these phenomena] do not exist at all.”

爾時世尊知而故問:“諸長者子!以何因緣而有惱色,憂愁不樂,失於常容?”時諸長者子同聲俱白佛言:“世尊,未審人居世間,頗有家宅吉凶以不?”佛即答言:“如是諸事,皆由眾生心行夢想所造,不得都無。”15(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911b2–6)

The Licchavi16 addressed the Buddha: “World-Honored One! [Because your] disciples (i.e., we) received (i.e., accumulated) the most minute (lit. ‘tip of a hair’) merits in our former lives, we are [now] able to see the Tathāgata who in his mercy transforms (i.e., teaches) everybody without remainder,17 opens the gate of sweet dew,18 and moistens us with the rain of the Dharma. But what kind of crime have we committed, that we are born into this utmost evil world [stained with] the five defilements?19 [We have to] embrace worries and suffering,20 are terrified in innumerable ways, not [being able to] get rid [of all the troubles] for a single moment. The reason why we speak like this is that the disciples’ (i.e., our) virtue is shallow and our merits meek. [Therefore,] the frequency of disasters and irregularities related to the residences we live in is increasing. Day and night, evil demons vie with each other to intrude [our homes], [leading to that] sitting and lying down (i.e., the daily activities) are not safe, [and it feels] like embracing hot fire.21 Lately, we have lost our good hearts (i.e., wholesome thoughts) and have nothing to rely on. We just wish that you, the World-Honored One, accept our request and personally descend to our homes, and help us pacify our residences. [We ask you to] issue an order to all the home-guarding spirits and the tabooed ones22 during the four seasons to permanently protect us, causing us to be safe and auspicious day and night, and the disasters to disappear.”

諸離車等白佛言:“世尊!弟子等蒙宿緣一毫之福,得覩如來,慈化無遺,開甘露門,潤以法雨。復有何罪生此五濁極惡之世,懷憂抱苦,怖懼萬端,不捨須臾。所以言者,自惟弟子德淺福薄。所居舍宅,災怪頻疊。惡魔日夜競共侵陵,坐臥不安,如懷湯火。自頃已來,失去善心,無所恃怙。唯願世尊受弟子請,臨降所居,賜為安宅。勅諸守宅諸神及四時禁忌,常來榮衛,使日夜安吉,災禍消滅。”(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911b6–15)

The Buddha said, “Splendid, splendid! I will do what you ask for, and I know myself at what time”.23 In the morning of the next day, the World-Honored One gave an order to his disciples that each of them should straighten their garment and enter the village. Each [of the disciples] carried an alms’ bowl24 and went to the residences of the elders. After (jìbì 既畢) having eaten their meal, they arranged a wheel-turning seat, and [the Buddha] proclaimed the profound Dharma for the elders, causing them to get rid of their fears and making their body and mind delighted.25 At that time, the Licchavi all felt joyful, just like a monk entering the third dhyāna heaven.26

At that time, the World-Honored One then called all the spirits protecting the residences. When they arrived at the place of the Buddha, he told them the following: “From now onward, all these spirits and demons should not arbitrarily terrorize [the inhabitants]. If you [spirits and demons] should make somebody unsafe and constantly feel worried, I shall send spiritual beings of great powers to exterminate you, causing you to turn into dust!”

佛言:“善哉!善哉!當如汝說,吾自知時。”爾時世尊明旦勅諸弟子:“可各整衣服,當入聚落。各持應器,往至長者子舍。”飯食既畢,敷轉輪座,為諸長者說微妙法,令離怖畏身心悅樂。時諸離車各生歡喜,猶如比丘入第三禪。爾時世尊即呼守宅諸神,來到佛所,而告之言:“自今已後,是諸神鬼,不得妄作恐動,令某等不安,恒懷憂怖。吾當使大力鬼神,碎滅汝身,令如微塵。”(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911b15–24)

At that time, the World-Honored One furthermore addressed the assembly: Men of good families, women of good families: Five hundred years after my nirvāṇa, [because of] the sentient beings’ impurities, their perverted views will become increasingly intense27 and [the inhabitants of] Māra’s realm will vie with each other to rise, and the demons will be acting wildly. They will peak into the gates of people[’s residences] and wait for the right opportunity (sì biàn 伺便) [to intrude upon them]. They will search for people’s strong points and shortcomings (lit. “long and short”), and [if the right occasion arises] create problems and all kinds of difficulties for them. At that time, you, the disciples, should single-mindedly recollect the Buddha, recollect the Dharma, recollect the Sangha. [According to] purification rituals, maintain the three refuges and five precepts, the ten kinds of wholesome behavior, and the eight precepts of the one-day vow holder. During the six periods of day and night, venerate, do repentance, and persevere with a diligent mind. Invite a monk of pure conduct to arrange a ritual for pacifying the residence; burn plenty of high-grade incense and lit a continuously bright lantern;28 [in addition,] outside in the center court read this scripture.

爾時世尊復告大眾:諸善男子善女人等,吾涅槃後五百歲中,眾生垢重,邪見轉熾,魔道競興,妖魅妄作,闚人門戶各伺人便,覓人長短,為作不祥種種留難。當爾之時,是諸弟子,應當一心念佛、念法、念比丘僧,齋戒清淨奉持三歸五戒十善八關齋戒,日夕六時禮拜懺悔勤心精進,請清淨僧設安宅齋29,燒眾名香然燈續明,露出中庭讀是經典30。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911b25–c3)

Ever since [the time] when people started building houses in order to dwell safely, [they] have constructed the southern covered hallway and the northern main hall, the eastern and western side mansions, the mansion for pounding rice, the storage room, the well, the stove, the gates and the walls, the garden groves and the ponds, as well as the enclosures for the six domestic animals. Sometimes, they move the earth when altering the building and drill holes at inappropriate times; sometimes they infringe on the Concealed Dragon,31 the Soaring Snake,32 the Azure Dragon, the White Tiger, the Vermilion Bird, the Black Tortoise,33 or offend the taboo of the liùjiǎ days,34 or the taboo of spirits of the twelve time periods of the day,35 the spirits of the gate, the courtyard, the windows, small alleys, the well, the stove, in the halls, the doors, and the toilet.

某等安居立宅已來,建立南庌北堂,東西之廂,碓磨倉庫,井竈門牆,園林池沼,六畜之欄。或復移房動土,穿鑿非時;或犯觸伏龍、騰蛇、青龍、白虎、朱雀、玄武、六甲禁忌、十二時神、門庭戶陌井竈精靈,堂上戶中溷邊之神。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911c3–c8)

I now rely on the divine power (shénlì 神力) of all the buddhas and the dignified prajnaparamita-power40 of the bodhisattvas. I order now the protecting spirits, who dwell in front of the residence, behind the residence, to the left of the residence, to the right of the residence, in the middle of the residence; sons of spirits, mothers of spirits, the Concealed Dragon, the Soaring Snake, the tabooed ones (i.e., spirits) of the liùjiǎ days, the spirits of the twelve [two-hour] periods, evil spirits such as the Flying Corpse,41 demons such as the wǎngliǎng,42 who by seizing their shape take possession [of the residents].

From now on, you should not falsely mingle with my disciples. Sons of the spirits, mothers of the spirits, all the spirits in the residence, the witchcraft of evil demons,43 the wǎngliǎng spirits, and Māra the Evil One, each [should] exist there peacefully, and should not arbitrarily intrude on [the residents], causing trouble for them, and letting them be startled and terrified. You should conform to my teaching, and if you do not follow my teaching, I will cause your heads to be crushed into seven pieces, like the twigs of a palm tree!44

我今持諸佛神力,菩薩威光般若波羅蜜力。勅,宅前、宅後、宅左、宅右、宅中守宅神,神子、神母、伏龍、騰蛇、六甲禁忌、十二時神、飛屍邪忤,魍魎鬼神,因託形聲,寄名附著:自今已後,不得妄嬈我弟子等。神子、神母、宅中諸神、邪魅蠱道、魍魎弊魔,各安所在,不得妄相侵陵,為作衰惱,令某甲等,驚動怖畏。當如我教,若不順我語,令汝等頭破作七分,如多羅樹枝。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911c9–c16)

[Having proclaimed this warning against unrestrained spirits, the Buddha then recites the following spell:]

At that time, the World-Honored One proclaimed the following spell:

Hail (Skt. namu) to the buddhas of the four directions;45

Hail to the Dharma of the four directions;

Hail to the Sangha of the four directions.

Today, for the sake of disciple so-and-so (mǒujiǎ 某甲), I rely on the mighty power of the Buddha and expound the following supernatural (powerful) spell:

One-legged beings—don’t bother us!

Two-legged beings—don’t bother us!

Three-legged beings—don’t bother us!

Four-legged beings—don’t bother us!46

I have great kindness and compassion, taking pity on all sentient beings.

All of you evil demons, go back where you belong!

You must not deliberately disturb and harass my disciples!47

爾時世尊而說呪曰:

南無佛陀四野

南無達摩四野

南無僧伽四野

今為弟子某甲承佛威力而說神呪:

一足眾生莫惱我 二足眾生莫惱我

三足眾生莫惱我 四足眾生莫惱我

我有一切大慈大悲愍念一切眾生,汝等惡魔,各還所屬,不得橫忓,擾亂我弟子等。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911c17–24)

The White-and-Black Dragon King

The Good Son Dragon King

The Blue Lotus Dragon King

Dragon King of the Dispassionate Lake

白黑龍王 善子龍王 漚鉢羅龍王 阿耨大龍王(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911c26–27)

The “zone” magical spell:49

The Bhagavat has arrived, the Bhagavat has arrived; svāha50! [??]

The great powerful Dragon King of the East—a zone of seven miles—adamantine residence51

The great powerful Dragon King of the South—a zone of seven miles—adamantine residence

The great powerful Dragon King of the West—a zone of seven miles—adamantine residence

The great powerful Dragon King of the North—a zone of seven miles—adamantine residence

Expound it three times like this.

結界呪文

伽婆致 伽婆致 悉波呵

東方大神龍王 七里結界 金剛宅

南方大神龍王 七里結界 金剛宅

西方大神龍王 七里結界 金剛宅

北方大神龍王 七里結界 金剛宅

如是三說(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 911c28–912a4)

Deep mountains of the pójiū of the southern direction—śālaka—restrain your hundred spirits and attach a cangue to their necks!

Deep mountains of the pójiū of the western direction—śālaka—restrain your hundred spirits and attach a cangue to their necks!

Deep mountains of the pójiū of the northern direction—śālaka—restrain your hundred spirits and attach a cangue to their necks!

Repeat this three times.

[All of you spirits who] bring about [that residents] are sick, have headache, and that people’s residences are not secure: You should restrain all poisons (i.e., malicious deeds), and you should not vex my disciples. If you do not obey my spell, your heads shall be crushed into seven pieces!

東方婆鳩深山娑羅伽扠(=収)汝百鬼頸著枷

南方婆鳩深山娑羅伽扠(=収)汝百鬼頸著枷

西方婆鳩深山娑羅伽扠(=収)汝百鬼頸著枷

北方婆鳩深山娑羅伽扠(=収)汝百鬼頸著枷

如是三說

主疾病者,主頭痛者,主人舍宅門戶者,當歛諸毒,不得擾我諸弟子。若不順我呪,頭破作七分。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 912a5–12)

At that time, the World-Honored One spoke the following ghāta:

Building a residence and setting up the rooms—raising the sentient beings in peace;

The garden and the pond—the gate, walls, and56 the privy;

Planning (lit. “give rise to a thought”) to build the rooms of the residence—all [building] activities should be in correspondence with the sagely spirits;

Bowing to the ground and taking refuge in the Buddha—then the multitude of demons will not be able to [cause the buildings to] collapse;

The power of the great spell of the Dharma-king—totally removes (lit. “move and destroy”) the infinite number of demons;

The compassion of the Tathāgata universally bestows happiness [to the sentient beings]—and his awe-inspiring light penetrates everywhere;

Don’t wait, all of you take refuge—and the multitude of evil [spirits] will by themselves move [away].

爾時世尊而說偈言:

造宅立堂宇 安育諸群生 /ʂiajŋ/

園林并池沼 門牆及與圊 /tshiajŋ/

起心興舍室 動靜應聖靈 /liajŋ/

稽首歸命佛 衆魔莫能傾 /khjwaijŋ/

明燈照無極 五眼因之生 /ʂiajŋ/

法王大呪力 動破魔億千 /tshian/

如來慈普潤 威光徹無邊 /pjian/

莫等咸歸命 衆邪各自遷 /tshian/(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 912a13–21)

The Buddha told [the spirits of] the sun, the moon, the five planets, and twenty-eight constellations, the heavenly beings, spirits, nāgas and demons: You should not take control (qiánquè 前卻) of the home of so-and-so (i.e., somebody’s home)! [When the inhabitants] construct the eastern corridor, western corridor, southern veranda, and northern hall, I command you, the Spirit of the Day, the Month Killer, the General of the Earth, the White Dragon, the Azure Dragon, the White Tiger, the Vermilion Bird, the Black Tortoise, the murderous spirits of the year and month [?],59 the taboo of the liùjiǎ days, the Crouching Dragon of the Earth, do not create havoc anywhere (lit. “east and west”)!

佛告日月五星、二十八宿、天神龍鬼皆來受教明聽。佛告言:不得前却某甲之家。或作東廂西廂南(庌)北堂,勅日遊月殺土府將軍、青龍白虎朱雀玄武、歲月劫殺六甲禁忌、土府伏龍莫妄東西。

(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 912a21–25)

If there is [still] any activity (dòngjìng 動靜) by the spirits, burn incense, and instruct [the spirits in the following way]:

The residence of so-and-so is the ground of the vajra of the Buddha,60 extending [in each direction] for 200 steps. The Buddha has made a pledge, that all disease-bringing demons and spirits should not be disobedient; the heads of those who are not obedient will be crushed into seven pieces,61 your bodies will not remain whole, and you will not get hold of broth (i.e., you will not have any basis for living and cannot survive), and you will have to leave your original mansion.62

若有動靜燒香啟聞:某甲宅舍,是佛金剛之地,面二百步。佛有約言,諸疫鬼神,不得妄忤,忤者頭破作七分,身不得全,不得水漿,去離本宮。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 912a21–28)

After [the construction of] one’s home has been completed, one will achieve good fortune and honors and auspicious promotions [in office], and the fields will greatly yield harvest according to one’s wishes. Honor and glory will pertain to military matters, to the service as official, and to one’s family, which will be prosperous and splendid. Among the countless descendants, the fathers will be merciful and the children filial. Sons and daughters will be loyal and dependable, the older brothers good-hearted and the younger brothers obedient. Honors, righteousness, benevolence, and virtuousness, everything will be according to one’s wishes. [The buddhas of] the ten directions will be witnesses (i.e., confirm that one will gain Buddhahood in the future), and practicing like the bodhisattvas, one will attain the way just as the Buddha did.

宅舍已成,富貴吉遷,田作大得,所願光榮,行來在軍,仕宦宜官,門戶昌熾,百子千孫,父慈子孝,男女忠貞,兄良弟順,崇義仁賢,所願如意。十方證明,行如菩薩,得道如佛。(T. 21, No. 1394, p. 912a28–b3)

Buddha told Ānan[da], “If you wish to pacify your residence, outside in the center courtyard, lit forty-nine torches, sweep [the ground] and burn incense; single-mindedly repent, and show reverence to all the buddhas of the ten directions.” Furthermore, Ānan[da] addressed the Buddha: “How shall we call this sūtra?” The Buddha told Ānan[da], “This sūtra is called the ‘The Inconceivable Divine Power of the Great Compassion of the Tathāgata.’ It is also called ‘The Divine Spell of Taking Pity on the Sentient Beings, Securing the Home, and Destroying Māra.’”

After the Buddha had finished expounding the sūtra, the great assembly rejoiced, venerated him, and made offerings.

The Sūtra Spoken by the Buddha of the Divine Spell for Securing the Residence.

佛告阿難,若欲安宅,露出中庭,然四十九燈,掃灑燒香,一心懺悔,禮十方諸佛。阿難又白佛言:當何名斯經?佛語阿難:此經名如來大悲不可思議神力。

亦名,愍念眾生安宅破魔神呪。佛說經竟,大眾歡喜,作禮奉行。

佛說安宅神呪經 (T. 21, No. 1394, p. 912b3–9)

5. The AZSZJ and the Introduction of Buddhist Practices for Pacifying One’s Home

5.1. Notes on Traditional Chinese Ideas Concerning Ānzhái

“The method of residences” is truly a secret technique. People certainly inhabit residences, there are just differences concerning the size, and concerning the nature of Yīn and Yáng [of the building]. Additionally, even if a guest dwells in a room [of one’s home], there will be still good and bad [influences on him]. If there is a major [influence on the inhabitants], then we talk about major [measures to be taken]. If there is a minor [influence on the inhabitants], then we talk about minor [measures to be taken]. If [the inhabitant] has offended against the prohibitions [concerning the residential spirits], then there will be disaster. If [these offenses] are warded off (zhèn 鎮), then the calamities can be stopped. It is just like the effect of a medicine for curing a disease. Therefore, the residence is the “origin” (or: foundation) of a person. A person makes a residence their home, and if the dwelling is peaceful, then the [subsequent] generations of the family will be prosperous. If [the residence] is not peaceful, then the clan will decline. The same holds true for graves in terms of their situation at riverbanks and mountains. As for the upper level [of society], such as the army and the state, subsequently [the intermediate level of society], such as the prefectures, counties, districts and cities, and those on the lower level [of society], such as the villages [when constructing] lanes, local offices, fences, and buildings on mountains, all are indeed examples of this (i.e., all of them have to obey the “method of residences”).

宅法,是真秘術。凡人所居,無不在宅。唯只大小不等,陰陽有殊。縱然客居一室之中,猶[有]善惡。大者大說,小者小論。犯者有災,鎮而禍止,亦猶藥病之效也。故宅者,人之本。人者以宅為家,居若安,即家代昌盛;若不吉,即門族衰微。墳墓川岡,並同茲説。上之軍國,次及州郡縣邑,下之村坊署柵乃至山居,但人所處皆其例焉。64

If the families of people have exhausted (lit. “emptied”) their resources, money and property have been lost, the members of the families are sick, or are not promoted in office. […] [As a remedy] use five liǎng of red orpiment, five liǎng of cinnabar, five liǎng of copper [?],65 five liǎng of white quartz, five liǎng of purple quartz (amethyst?), and insert these items above (lit. “to the right”) into a rock which you place in the center courtyard, and subsequently bury them three inches deep [together] with multicolored silk; [these measures] will cause the families of the people’s residences to be auspicious.

凡人家虛耗,錢財失,家口不徤,官職不遷……用雄黃五兩,朱砂五兩,砂青五兩,白石英五兩,紫石英五兩,右件等物,石函盛之,置中庭,以五色綵隨埋之,深三尺,令人宅家(吉)。66

5.2. A Short Discussion of the Indian Background

Śramaṇa Gautama rejected drinking wine, did not get attached to fragrant flowers; did not watch [the performance of] songs and dances; did not sit on elevated seats; did not eat at inappropriate times; did not possess gold and silver; did not amass a wife or offspring, male servants, or maid servants; did not possess elephants and horses, pigs and goats, chickens and dogs, and birds and beasts; did not amass elephant riders, cavalry, charioteers, and infantry; and did not possess fields and residences, growing the five types of grains. […] These are the minor preconditions for observing the prohibitions.

沙門瞿曇捨離飲酒,不著香華,不觀歌舞,不坐高床,非時不食,不執金銀,不畜妻息、僮僕、婢使,不畜象馬、猪羊、鷄犬及諸鳥獸,不畜象兵、馬兵、車兵、步兵,不畜田宅種殖五穀……此是持戒小小因緣。(Cháng āhán jīng 長阿含經; T. 1, No. 1, p. 89a5–14)

You originally entered this mountain because of two matters (i.e., reasons). What are those two? First, you regard your wife and home as your prison and, second, your sons and relatives as your shackles. Thus, you came here to seek the way to disrupt the suffering from the cycle of life and death. But now you wish to return home, again becoming attached to the shackles and enter the prison; this [being immersed in] loving affection and caring feelings [for your family] will direct [you] toward hell.

卿本以二事故來入此山中。何等為二?一以妻婦舍宅為牢獄故,二以兒子眷屬為桎梏故。卿以是故來索求道,斷生死苦。方欲歸家,還著桎梏入牢獄中,恩愛戀慕徑趣地獄。(T. 4, No. 211, p. 601a21–25)

Non-Buddhist śrāmaṇera and brahmins eat the alms food of those of other faiths, [although] they practice a teaching which blocks the right way,68 and they do not earn their livelihood properly; some recite spells concerning water and fire, some make demonic incantations, some chant spells of the kśatriyas, some recite “elephant spells,” some spells concerning body parts, some talismanic spells concerning the pacification of one’s home […]. Śrāmaṇa Gautama does not involve in this kind of things (i.e., activities).

如餘沙門、婆羅門食他信施,行遮道法,邪命自活。或呪水火,或為鬼呪,或誦剎利呪,或誦象呪,或支節呪,或安宅符呪,…沙門瞿曇無如此事。(Cháng āhán jīng 長阿含經, T. 1, No. 1, p. 89c5–10)

When bhikṣus involved in the construction are about to determine the foundation [of the structure], they should obtain an auspicious time according to the star [deities]; if there are no lay people around, they themselves should insert a peg into the land (lit. “with a peg nail the earth”) in order to demarcate the territory that they want to build on; if it is [only] four fingers deep, there is no offense [against the monastic rules].

若營作苾芻欲定基時,得好星候吉辰,無有淨人,應自以橛釘地欲記疆界,深四指者無犯(Gēnběn shuō yīqiè yǒubù Pínàiyè 根本說一切有部毘奈耶, T. 23, No. 1442, p. 854b13–15)

If one protects one’s home, one should smear 1.800 stalks of lotus flowers with black sesame oil and recite the mantra of the “Mother dhāraṇī,” the secret mantra of the [true] mind, and the mantra of the fierce kings (mahārājas) and perform fire rituals;71 then, one will eradicate all disaster in one’s home.

若護宅者,當以蓮花一千八莖,塗黑芥子油,誦持母陀羅尼真言、祕密心真言、奮怒王真言,加持護摩,即除宅中一切災疾。(T. 20, No. 1092, p. 267c10–13)

5.3. Concrete Strategies of the AZSZJ

If the family is afraid without any obvious reason, then this is caused by the strange behavior of demon spirits. […] [As a remedy,] cut off the head of a chicken and place it above the door, pour the blood of a goose into a vessel, mix it with the husk of millet, and smear it on the gates, doors, wells, stove, and privy. Then there will be no harm.

人家無故恐者,皆是諸鬼精變恠使然……断鷄頭置門上,醘鵝血和黍糠以塗門户井竈溷,無咎矣。

At that time, the Buddha addressed the great assembly: “People of the world are deluded by ignorance, those having faith in the Buddha are few, and those believing in mistaken [teachings] are many. Fake masters are deceitful and cause the people of the world to have nothing to rely on, and those foolish people of shallow knowledge are just like cows following their owner. Later, when they encounter inauspicious and adverse circumstances, they ask a master to pacify their home, and he performs a blood sacrifice. These are all deluded commoners, and the sins they accumulate are numerous. Today, I have compassion with them, and will concisely teach the method of pacifying one’s residence.”

爾時佛吿一切大眾:“世人愚惑,信佛者少,信邪者多。邪師欺誑,致使世人無所歸趣,淺識愚迷,如牛隨主。後不吉利,諸不諧偶,請師安宅,煞生禱祀。此皆誑惑凡人,獲罪不少。吾今愍之,略教安宅之法。”73

6. Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBC | Chinese Buddhist Canonical Attributions Database, ed. by Michael Radich and Jamie Norrish (https://dazangthings.nz/cbc/). |

| CBETA | Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association (CBETA), based on the Taishō Tripiṭaka 大正新修大蔵經 (Daizo Shuppansha 大藏出版株式會社). https://www.cbeta.org/. [All citations of the T. canon are from the digitized versions in CEBTA.] |

| DDB | Digital Dictionary of Buddhism; Charles Muller (ed.). http://www.buddhism-dict.net/ddb (accessed on 12 October 2021). |

| Дx | Dūnhuáng manuscripts kept in the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg. |

| MC | Medieval/Middle Chinese. |

| P. | Dūnhuáng manuscripts of the Pelliot collection at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| S. | Dūnhuáng manuscripts of the Stein collection of the British Library. |

| T. | Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎et al. (eds.). 1924–1935. Taishō shinshū dai zōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 [Newly revised edition of the Buddhist Canon in the Taishā-era]. 100 volumes. Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai大藏出板會. [T. references from CBETA] |

| X. | Xùzàngjīng 續藏經. Táiběi: Táiwān xīnwénfēng chūbǎn gōngsī 台灣新文豐出版公司, 1993. |

| 1 | The importance of the right time and location when building or renovating is emphasized in a variety of medieval Chinese sources, e.g., the Lùnhéng 論衡 (“When erecting a home and building a structure, one has to select the [right] day.” 起宅蓋屋必擇日; p. 995); in order to avoid the disturbance of domestic spirits, traditionally, before the building process is initiated, various practices have to be performed to determine the auspicious timing and location. For a discussion of ānzhái practices in medieval Dūnhuáng, see, for example, (Yúzhù Chén 2007, pp. 169–74). |

| 2 | For a thorough discussion, see (Jones 2010). |

| 3 | In the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, the title of the scripture is translated as “Spirit-Spell Scripture for Pacifying Homes.” The “sūtra” is classified as an apocryphal; see (Buswell and Lopez 2014, p. 56). In canonical Buddhist literature, the term ānzhái very rarely appears. Qímíng Zhāng (2011, p. 84) remarks that in the Chinese context, ānzhái was first used during the Wèi 魏 period (220-266), although he dates the composition of the AZSZJ to the end of the Hàn dynasty. Terms related to ānzhái can indeed be traced to the Hàn dynasty, such as ān zhǒngmù 安冢墓 “pacify the tomb.” However, according to the current evidence, we find the early dating of the AZSZJ unconvincing. According to Zhāng Qímíng, ānzhái originally referred to taboos concerning dwellings and graves. In later periods, other terms were usually preferred when referring to similar practices, such as bǔzhái 卜宅, xiàngzhái 相宅, xiàngmù 相墓, etc. More generally, on Chinese apocryphal Buddhist scriptures, see (Buswell 1990a, 1990b; Tokuno 1990; Kuo 2000; Cáo 2011). |

| 4 | By this, Sēngyòu means that he personally inspected these texts, confirmed their authenticity, and included them in his catalogue. The Xīnjí xùzhuàn shīyì zájīng lù section consists of two parts: The first is referred to as yǒu běn 有本 (“there is an [extant] text version”), including 846 texts which have been seen as physical entities by Sēngyòu. The second part, wèi jiàn qí běn 未見其本 (“[I] have not yet seen these volumes/texts”), consists of texts that were not extant anymore or that he had not personally seen (including 460 titles). Both the Qīfó ānzhái shénzhòu and the Ānzhái zhòu are included in the yǒu běn part. |

| 5 | Rénjiān jīngzàng 人間經藏 most likely refers not to any “canonical” scriptures but rather to (often-apocryphal?) Buddhist texts circulating among the general populace. |

| 6 | Catalogues vary insofar as whether they add the formula fóshuō 佛說 (“expounded by the Buddha”) to Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng 安宅神呪經. In his Yīqiè jīng yīnyì 一切經音義, Táng scholar-monk Huìlín 慧琳 first uses Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng in his overview of scriptures but uses Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng in the actual discussion of the text. Clearly, he refers to one and the same scripture (T. 54, No. 2128, p. 589a21 and p. 590c10–17). |

| 7 | For a critical edition, see (Juān Xióng 2015, pp. 223–26). |

| 8 | The Saihō-ji 西方寺 manuscript has the following colophon: 人平二年十月十六日交了,悲母尊靈成佛得道也。 願主慶尊智成(花押), including a date when it was copied and a dedication to the soul of the deceased mother. The date indicates that it was copied on the 16th day of the 10th month of the Ninpei era (1151-1154), i.e., 1152. The Nanatsu-dera manuscript (ms. #611 in the catalogue) does not have a colophon, just a note that it was copied by a scribe by the name of Eigei (一校了永藝; Nakao and Honmon Hokkeshū Daihonzan Myōrenji 1997, p. 250). However, we can assume that it was copied between 1178 and 1181, the period to which most manuscript copies of the Nanatsu-dera canon are dated; on this canon, see (Keyworth 2016; Ochiai et al. 1991). According to its colophon, the Matsuo-sha 松尾社 manuscript version was produced around the 1140s, where the copy was made from an exemplar stored at that time at Amidabō 啊彌陀房 on Mt. Hiei; on these manuscripts, see (Nakao 1996). Unfortunately, we were unable to directly access the digitized versions of the Japanese ānzhái manuscripts (they are currently accessible only from within Japan). |

| 9 | For further information, please consult (Jīngpéng Shǐ 2016, p. 171). |

| 10 | P.3915 is in pothi form and consists of 50 oblong sheets (ca. 39 × 9 cm, with numbers on the recto side), with texts on both the recto and verso sides. The sheets are numbered and sheets 32 and 33 are missing. The copy is dated to the 10th century. P.3915 features several texts: the last section of the Lè rù shān zàn 樂入山讚 (“Eulogy of Rejoicing of Entering the Mountains”); Lè zhù shān [zàn] 樂住山[讚] (“[Eulogy of] Rejoicing of Dwelling in the Mountains”); one fascicle of Kumārajīva’s translation of the Jīngāng bōrě bōluómì jīng 金剛般若波羅蜜經 (Skt. Vajracchedikā-prajñāpāramitā-sūtra); the 25th fascicle of the Lotus Sutra, Guānshìyīn púsà pǔmén 觀世音菩薩普門 (“Universal Gate of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva”); one fascicle of the Āmítuó jīng 阿彌陀經 (Skt. Amitabha sūtra); two versions of the Fóshuō bāyáng shénzhòu jīng 佛說八陽神咒經 (“Spell Sūtra of the Eight Principles [of Heaven and Earth] Spoken by the Buddha”); and the Bāmíng pǔmì tuóluóní jīng 八名普蜜(密)陀羅尼經 ("Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Universal and Secret Eight Names”), a translation attributed to Xuánzàng 玄奘. The Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng can be found on sheets 34v, 35r, 35v, 36r, and 36v. For a critical edition of the two Dūnhuáng versions, see (Juān Xióng 2015, pp. 226–28). |

| 11 | For an edition, see (Juān Xióng 2015, pp. 223–26). |

| 12 | Typically, this consists of a multitude of anonymous bodhisattvas, monks, nuns, lay practitioners, and the eight kinds of spiritual beings, i.e., deva, nāga, yakṣa, gandharva, asura, garuḍa, kiṃnara, and mahoraga. In name, the disciples Śāriputra, Mahāmaudgalyāyana, Mahākāśapa, Mahākātyāyana, and Subhūti are mentioned, in addition to the bodhisattvas Mañjuśrī, Dǎoshǐ Bodhisattva (導師菩薩), Ākāśagarbha (Xūkōngzàng púsà 虛空藏菩薩), and Avalokiteśvara. |

| 13 | Líchē 離車, i.e., a member of the ruling class of Vaiśālī, in Jain and Buddhist sources described as politically progressive and tolerant to a variety of religions. |

| 14 | Zhǎngzhě can translate Skt. gṛhapati and śreṣṭhin and perhaps here refers not to “elders” but rather to the heads of rich households. |

| 15 | Occasionally, we modified the original Taishō and CBETA punctuation. |

| 16 | The plural is redundantly expressed here, with the quantifier zhū 諸 “all” preposed to Líchē and followed by the plural suffix děng 等. The Chinese compilers of the text skillfully implanted typical features of Buddhist Hybrid Chinese. |

| 17 | Wúyí 無遺, lit. “without remainder; without anything being left out” > “everybody without exception”. |

| 18 | Gānlù 甘露, “sweet dew; nectar” is a metaphor for the teaching of the Buddha. |

| 19 | Wǔzhuó èshì五濁惡世; this is an expression frequently used in Buddhist canonical literature, e.g., in the Lotus sutra: “All buddhas are born into the evil world of the five defilements, which consists of the defilement of the [present] kalpa (jiézhuó 劫濁), the defilement of afflictions (fánnǎozhuó 煩惱濁), the defilement of [being] a sentient being (zhòngshēngzhuó 眾生濁), the defilement of (having mistaken) views (jiànzhuó 見濁), the defilement of having a (shortened) lifetime (mìngzhuó 命濁)”; 諸佛出於五濁惡世,所謂劫濁、煩惱濁、眾生濁、見濁、命濁。(Miàofǎ liánhuá jīng 妙法蓮華經; T. 9, No. 262, p. 7b23–24). |

| 20 | Huái yōu bāo kǔ 懷憂抱苦 > huáibāo yōukǔ 懷抱憂苦 (for rhetorical reasons, the two disyllabic words are “nested” into each other). |

| 21 | The expression huáitāng huǒ appears in the Shēng jīng 生經 (無得臨壽終心中懷湯火; Jātaka sūtra; T. 3, No. 154, p. 74a1–2) and the Buddhacarita 佛所行讚 (我心懷湯火不堪獨還國; T. 4, No. 192, p. 11c1), expressing the deepest despair, comparable to suffering torture in hell. |

| 22 | Jìnjì 禁忌, with early examples in the Lùnhéng, literally means that certain actions should not be carried out during specific times (calendar taboos). Concretely, in this passage 四時禁忌 refers to the spirits which should not be offended against during the four seasons. Thus, jìnjì could be interpreted as “taboo > tabooed one (subject nominalization) > spirit that one should not offend against.” |

| 23 | With this, the Buddha indicates the proper timing for his sermon on this issue. |

| 24 | Yīngqì 應器 is syn. to bō 鉢 “begging bowl; alms’ bowl” (Skt. pātra). |

| 25 | Compare the more frequently used shēnxīn ānlè 身心安樂 “body and mind being at comfort”. |

| 26 | This refers to a deep state of contemplation, during which a feeling of joy transforms into a state of serenity and calmness (for a taxonomy of meditative states, see, for example, the Abidharma-kośa; the third meditation heaven is, for example, mentioned in T.25, No. 1509, p.120b4). |

| 27 | Chì 熾 is interpreted as chíshèng 熾盛 here, “blazing > abundant; intense.” |

| 28 | This is an altar lamp that burns day and night (chángmíng dēng 常明燈). |

| 29 | Zhāi has several meanings and originally refers to a vegetarian meal that is served to monks, or more generally, it refers to rituals or ceremonial acts during designated days. Zhāi usually includes purification and/or confession rituals. The “ritual of securing one’s residence” (ānzhái zhāi 安宅齋) was eventually also integrated into the Daoist ritual repertoire, as can be deducted from Sòng dynasty and Yuán dynasty texts, such as the Língbǎo lǐngjiào jìdù jīnshū 靈寶領教濟度金書, a ritual manual of the Língbǎo School where we find the following statement: “Generally, when people move the earth to build a house, it is likely that they will offend the spirits, and disaster can arise easily; [therefore] it is appropriate to perform the ‘ritual of securing the residence’” (凡人動土架屋,恐有觸犯土神,易生災患,宜修靈寳安宅齋。; Dàozàng, vol. 7: 41). |

| 30 | The idea that the recitation of Buddhist scriptures makes one’s home safe is frequently encountered in esoteric scriptures and Indigenous Chinese Buddhist texts. For example, see the Shǒuhù dàqiān guótǔ jīng 守護大千國土經 (Sūtra of Protecting the Great Thousand Lands; Skt. Mahāsāhasrapramardanī-nāma-mahāyānasūtra): “Furthermore, World-Honored One, if there is a person who in his own home, for one day and one night, recites this Shǒuhù dàqiān guótǔ dàmíngwáng jīng, then this person’s home will not have any troubles or inauspicious matters for one year” (世尊,若復有人於已舍宅,一日一夜讀誦如是守護大千國土大明王經,是人舍宅一歲之中,無諸衰患,不吉祥事。; T. 19, No. 999, p. 592a29–b2). Similar recommendations can be also found in Sòng dynasty and Yuán dynasty Daoist scriptures, such as the Tàishàng jiǔtiān yánxiáng dí’è sìshèng miàojīng 太上九天延祥滌厄四聖妙經, which states the following: “When one newly builds a residence, and commences with the work of moving the earth, and violates against the forbidden directions [where the spirits dwell], then one should lit seven candles in the middle of the courtyard, prepare five seasonably fresh fruits, burn all kinds of high-grade incense, and whole-heartedly recite this scripture facing the northern direction” (新蓋宅宇,動土興工,犯觸禁方,當於中庭燃燈七盞,備時新五菓,燒種種名香,至心望北念經。; Dàozàng, vol. 1: 810). |

| 31 | Fúlóng 伏龍, “Concealed Dragon,” may refer to the spirit of the stove here (see, for example, the Róng zhāi sì bǐ 容齋四筆; “If the Fúlóng is present, one should not engage in moving; what is called ‘Fúlóng’ refers to the spirit of the stove” 伏龍在,不可移作,所謂伏龍者,竃之神也。(ed. in Róng zhāi suí bǐ 容齋随筆: 667)). |

| 32 | The Soaring Snake (téngshé 騰蛇) has several meanings in the mythology of China, and it can refer to a dragon-like creature; see, for example, the Liùchén zhù wénxuǎn六臣註文選: “It resembles a dragon and is also a beast from the north” (似龍,亦北方獸也。). In addition, téngshé can refer to a spirit of ashes; see, e.g., Wǔxíng dàyì 五行大義 (p. 277): “The Soaring Snake dwells at the end of the fire (i.e., ashes) and exists in the beginning of the earth; [thus,] it is (or: becomes) the spirit of the ashes” (騰蛇居火之末,在土之初,而爲灰神). Probably, this means that the Soaring Snake exists at the point of transformation from the element of fire into the element of earth. In addition, the term can refer to a celestial constellation, e.g., Jìnshū 晉書 (p. 296): “The Soaring Snake [constellation] consists of twenty-two stars and is situated in the north of the Yíngshì (‘House’) constellation” 騰蛇,二十二星,在營室北。). |

| 33 | The Azure Dragon, the White Tiger, the Vermilion Bird and the Black Tortoise refer to the four divisions of the 28 Lunar Mansions (二十八宿), representing the guardians of the four directions; see, for example, the Hàn dynasty Sān fǔhuáng tú 三輔黄圖 (p. 14): 蒼龍、白虎、朱雀、玄武, 天之四靈, 以正四方。 |

| 34 | Liùjiǎ 六甲 refers to the six days, including the Heavenly Stem jiǎ, of the 60-day cycle (i.e., 甲子, 甲寅, 甲辰, 甲午, 甲申, 甲戌). During these days, protection against malignant spirits is especially important. |

| 35 | This refers to the 12 2-hour divisions of the day. |

| 36 | In order to avoid the improper and inauspicious encounter with spirits, it is important to calculate their movement and location at specific times. As for the movement of spirits residing in one’s dwelling, the Chì Sōngzǐ zhānglì 赤松子章曆 (p. 185) mentions the following activities:

The Chì Sōngzǐ zhānglì (p. 185) also mentions the exact days for the spirits’ movement; for example, if the spirits leave on the rénxū (i.e., 59th day of the 60-day cycle), they will return on the jiǎzǐ (i.e., 1st day). The text emphasizes that one also should know the exact time of the spirits’ movement. References to the importance of appropriate timing in construction work can also be traced to early Chinese texts, such as the Qín dynasty bamboo slips found at Shuì hǔ dì 睡虎地. In a text called Rìshū 日書 (“Daybook”) appears the following passage, with a warning to build a house on certain dates:

|

| 37 | On a study of medical Dūnhuáng scriptures concerning the hemerological methods that use the annual calendar to determine the movement of the “Day Spirit,” see (Arrault 2010). Determining the movement of this spirit was especially important for birthing practices. |

| 38 | This is an inauspicious “Day Spirit,” already appearing in daybook hemerologies of the Hàn period; see (Liu 2017, p. 82; Smith 2017, p. 345). |

| 39 | A prognostication text with references to the Five Planets, the Wǔxīng zhàn 五星占 was excavated at Mǎwángduī 馬王堆, 2nd century BC; see (Morgan 2016). |

| 40 | The term “prajñāpāramitā power” (bōrě bōluómì lì 般若波羅蜜力 “power of the perfection of wisdom”) appears in several prajñāparāmitā sūtras, such as the Móhē bōrě bōluómì jīng 摩訶般若波羅蜜經 (e.g., T. 8, No. 223, p. 272c15) and the Xiǎopǐn bōrě bōluómì jīng 小品般若波羅蜜經 (e.g., T. 8, No. 227, p. 539c2). It has an especially high frequency (appearing 11 times) in the Dàzhì dùlùn 大智度論. The compound púsà wēiguāng 菩薩威光, lit. “awe-inspiring light of the Bodhisattva,” is a rare expression in canonical Buddhist texts (see, for example, Pǔyào jīng 普曜經, T. 3, No. 186, p. 497c17; Fāngguǎng dàzhuāngyán jīng方廣大莊嚴經, T. 3, No. 187, p. 560c6; Fóxīn jīng 佛心經, T. 19, No. 920, p. 4a20). |

| 41 | In traditional Chinese medicine, fēishī 飛屍 was also used as a term for tuberculosis; see (Ma 2019, vol. 1, p. 683). In an early mention in the Lùnhéng (p. 1043), fēishī more generally refers to demons’ temporarily residing in one’s home (宅中客鬼). In Buddhist scriptures, the term can indicate demons’ causing lung illnesses such as tuberculosis (see, for example, Fǎjiè shèngfán shuǐlù shènghuì xiūzhāi yíguǐ 法界聖凡水陸勝會修齋儀軌 CBETA, X. 74, No. 1497, p. 806a10–15). Other texts mentioning this demon (in addition to other spirits mentioned in the AZSZJ) include the Dàodì jīng 道地經 (T. 15, No. 607, p. 234c24), the translation of which is attributed to Ān Shìgāo 安世高. |

| 42 | Wǎngliǎng 魍魎 (罔閬/罔兩/蝄蜽) is the name of a malevolent spirit; the term had already been used in classical Chinese literature. Originally referring to a specific type of demon, it is also used in medieval China as generic term for “demons; monsters; evil spirits.” In Buddhist translation literature, it can translate Skt. vyāḍa (DDB) as “a noxious spirit or monster that dwells in forests and crags lying in wait for human victims.” For a discussion of the term, see also (Kósa 2013, pp. 39–43): “are malevolent beings in the tomb that will harm the dead if they are not exorcised.” Reference to this demon can be found in several Buddhist scriptures, both canonical and apocryphal (e.g., Fómíng jīng 佛名經; T. 14, No. 441, p. 225b24; Dìzàng púsà běnyuàn jīng 地藏菩薩本願經; T. 13, No. 412, p. 784a18). Here, the Dūnhuáng version of the text uses four characters in a sequence, collectively referring to all kinds of demons, wǎngliǎng-bá-wèi 魍魎魃魅 (P-3915-33v-05). |

| 43 | Gǔdào 蠱道 can mean “method of incantation” but might refer to a specific spirit here. |

| 44 | Duōluó 多羅 “palm tree” (Skt. tāla). |

| 45 | Instead of sìfāng 四方, the text has sìyě 四野 “four open lands/wildernesses”; this expression is relatively rare in Buddhist texts but is occasionally used in traditional Chinese literature (e.g., wàng sìyě 望四野 “face the four directions”; Mù tiānzǐ zhuàn 穆天子傳, p. 110). |

| 46 | Here, the Buddha addresses spiritual beings of different forms and shapes. In Buddhist texts, we found reference to “no-legged beings” (wúzú zhòngshēng 無足眾生), “two-legged beings” (èrzú zhòngshēng 二足眾生), “three-legged beings” (sānzú zhòngshēng 三足眾生), and “four-legged beings” (sìzú zhòngshēng 四足眾生), e.g., Dàzhìdù lùn 大智度論: 有色眾生無色眾生,無足二足四足多足眾生。 (Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra; T. 25, No. 1509, p. 279c9–10). Mention of beings with one leg is scarce; however, a reference is included in a passage of the Guòqù xiànzài yīnguǒ jīng 過去現在因果經, fascicle 3:有形、無形、無足、一足、二足、四足、多足,一切眾生,無不悉有如此苦者。 (CBETA, T. 3, No. 189, p. 644b21–22). |

| 47 | Hénggān 橫忓 is an expression that occurs only three times in CBETA. 忓 should probably be interpreted here as meaning wǔ 忤 “unfilial; not obedient; deviating; uncontrolled,” although there is no match in CBETA or any non-Buddhist source that we checked. According to the Yùpiān 玉篇 (p. 73), 忓 has the semantics of rǎo 擾 (“disturb”), which fits well in the context. |

| 48 | Here, the text heavily draws on a passage from the Mahāsāṃghika vinaya (Móhē sēngqí lǜ 摩訶僧祇律), translated during the Eastern Jìn, where the protective power of the four nāga kings is invoked:

To the best of our knowledge, our text and the Mahāsāṃghika vinaya are the only sources in the Taishō canon that mention the terms 善子龍王 and白黑龍王. However, they appear in reverse sequence: 黑白龍王 (Móhē sēngqí lǜ摩訶僧祇律; T. 22, No. 1425). Shànzǐ, lit. “good son,” is rendered as a translation of Skt. Kuśala-pota; see (Hirakawa 1997, p. 533a). His rendering as kuśalapota, which occurs only in the Abhidharmakośbhāṣya as a metaphor for good (kuśala) actions being carried like a tiger carries her young (pota), is also unexpected, as one would expect kuśalaputra (“good son”). The term ānòu dàlóng 阿耨大龍 refers to *Anavatapta nāgarāja (阿那婆達多龍王); he is said to reside in a lake north of the Himalayas and is mentioned in the Tiānpǐn miàofǎ liánhuá jīng 添品妙法蓮華經 (Saddharmapuṇḍarīka sūtra/Lotus Sutra; translated in 601) as one of the eight protective dragon kings (see DDB, entry “阿那婆達多龍王”; accessed 12 December 2021). Ōubōluó 漚鉢羅 renders Skt. Utpala (“blue lotus”; Hirakawa 1997, p. 744a) and is also one of the eight dragon kings mentioned in the Lotus Sutra: 難陀龍王 [(Nandopa)nanda nāgarāja], 跋難陀龍王 [Upananda nāgarāja], 娑伽羅龍王 [Sāgara nāgarāja], 和脩吉龍王 [Vasūki nāgarāja], 德叉迦龍王 [Takṣaka nāgarāja], 阿那婆達多龍王 [*Anavatapta nāgarāja], 摩那斯龍王 [Mānasa nāgarāja], 漚鉢羅龍王等 [*Utpala nāgarāja] (T. 9, No. 264, p. 135a28–b1). 阿耨大龍 is rarely mentioned in the Buddhist canonical texts, and most of the references can be found in the Fóshuō xīngqǐ xíng jīng 佛說興起行經, where this dragon king is one of the protagonists. Another mention is in the Qī Fó bā púsà suǒshuō dà tuóluóní shénzhòu 七佛八菩薩所說大陀羅尼神呪經 (T. 21, No. 1332, p. 540c26). An early occurrence of 漚鉢羅 can be found in the Tiānpǐn miàofǎ liánhuá jīng 添品妙法蓮華經 (T. 9, No. 264, p. 135b1). As for 漚鉢羅 (also written 嗢鉢羅, 優鉢釗, etc.), Huìlín’s 慧琳’s Yīqiè jīng yīnyì has the following comment: 殟鉢羅,云是紅蓮花,有作優鉢,應從殟為正也 (T. 54, No. 2128, p. 483a6). In his work, he mentions only the meaning “red lotus,” and there is no mention of the name of a nāga king. As for 難陀龍王, it is perhaps unnecessary to reconstruct (Nandopa)nanda and just have Nanda, following the Chinese, which is the name of a nāga often found together with Upananda. According to (Edgerton 1970, pp. 289–90), Nandopananda, as the name for a nāga, occurs only once in the singular in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya and is more commonly found as a dual, meaning Nanda and Upananda are distinct more often than not (we thank Henry Albery for this information). |

| 49 | Jiéjiè 結界 is an important concept (especially in esoteric Buddhism), indicating a defined area or territory for carrying out religious practices and observances. Here, it concretely refers to the “zone” around the residence that cannot be intruded on by malicious spirits. In this passage, the protection of the zone of each direction by the corresponding nāga king is invoked. |

| 50 | 悉波呵 usually appears at the end of incantations/dhāraṇī as an (unusual) transliteration of Skt. *spāha/svāha; see (Karashima 2020, p. 4). For 伽婆致, there is no other reference found; therefore, we tentatively interpret 致 semantically and not as part of the phonetic transcription. Possibly, 伽婆 is an abbreviation of 婆伽婆, “Bhagavat,” an epithet of the Buddha. As Henry Albery has suggested, 致/至 could be interpreted as rendering the ending -ti or -te, thus transliterating (*bha)gavati svāha or (*bha)gavate svāta. However, at this point, all these interpretations are speculative. |

| 51 | There is a direct parallel to this spell in the Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng 孔雀王呪經 (“Peacock Sutra”), a scripture of somewhat unclear origin, which adds a fifth line with the “great powerful dragon king of the center”:

The central term is jīn’gāng zhái 金剛宅, “diamond residence,” probably indicating that one’s residence is as solid and hard as a diamond and as such impenetrable for demonic beings. The translation of the scripture is attributed to Kumarajīva, but the Yīqiè jīng yīnyì classifies it as “partly fake sūtra” (bàn shì wěijīng 半是偽經): 又有一本孔雀王呪經,約九紙,題云姚秦羅什譯。從頭有三紙半是偽經。無識愚人添加此文,即文中云七里結界金剛宅收汝百鬼項著枷,又云仙人鬼大幻持呪王等是偽也。從此南無佛南無法已下約五六紙是真經。智者尋攬自鑒取真偽,甚宜除去前偽文也。 (T. 54, No. 2128, p. 554c22–555a3). This text consists of a multitude of spells and the (often-repetitive) incantation of magical sounds. Huìlín assumes that the part beginning with 南無佛南無法南無僧 is authentic (T. 19, No. 988, p. 483a4–484c9). Importantly, the parallel parts to the Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng are included in the “fake” section of the Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng. |

| 52 | Pójiū 婆鳩 *baku [?]; there is also mention of a 婆鳩神 in a list of the names of 15 spirits in the Explanation of the Treatise on Mahāyāna, a commentary to the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna (Shì Móhēyǎn lùn 釋摩訶衍論; T. 32, No. 1668, p. 658b3); on this text, see CBC: https://dazangthings.nz/cbc/text/1507 (accessed on 15 March 2022). We could not trace any other occurrence of 婆鳩 in Buddhist scriptures. Possibly, 婆鳩 here generally refers to harmful spirits; therefore, a more readable translation could be the following: “Those harmful spirits in the deep mountains of the east, leader/king of the spirits (娑羅伽?), restrain all the spirits belonging to you and attach a cangue to their necks.” In Buddhist scriptures, we find expressions referring to spirits and demons, such as 薄鳩羅夜叉 (Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng, T. 19, No. 984, p. 451a4), 摩鳩羅鬼 (Zá āhán jīng 雜阿含經, T. 2, No. 99, p. 362b9), and 薄俱羅鬼 (Biéyì zá āhán jīng 別譯雜阿含經, T. 2, No. 100, p. 480b28). In these expressions, phonetically, 薄鳩 /bak-kjuw/, 摩鳩 /ma-kjuw/, and 薄俱 /bak-kju/ are very similar to 婆鳩 /ba-kjuw/. We conclude that 婆鳩 might be an abbreviated form of 薄鳩羅/摩鳩羅/薄俱羅, which can refer to a demon (Skt. Vakkula). According to Henry Albery the most common rendering of the name of this yakṣa is Bakkula, which is also the name of a monk who, incidentally, is also the foremost disciple of the Buddha with regard to health/medical knowledge. |

| 53 | Suō/shāluójiā/qū娑/沙羅伽/佉 usually refers to the śāla(ka?) tree. According to the Fóshuō guàndīng jīng 佛說灌頂經, it can be also (part of) the name of a spirit (神名檀特羅沙羅佉羊馱; T. 21, No. 1331, p. 495c22); in the same scripture, it is referred to as a spell, uttered when finishing the incantations during a guàndīng “consecration” ceremony (呪欲竟時三說沙羅佉; T. 21, No. 1331, p. 517a25). Or does it rather refer to a protective deity here? Also compare the Fóshuō què wēn huáng shénzhòu jīng 佛說却溫黃神呪經, Sūtra of the Plague-Dispelling Incantation (Xùzàngjīng 續藏經, Vol. 3: 776); in this apocryphon, the Buddha instructs his disciples on how to dispel the plague, by reciting the names of seven spirits that cause the disease. The names of the spirits are based on the Fóshuō guàndīng jīng and are seemingly transliterated from Sanskrit; however, it is probably “pseudo-Sanskrit” and not actually based on Indic words, but rather it probably aims at producing exotic-sounding spells. Therefore, the “reconstruction” śālaka is purely hypothetical. On the Fóshuō què wēn huáng shénzhòu jīng, see (Enso 2009); see also the DDB entry “却溫黃神呪經” (consulted 3 May 2022). In the Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng, the rendering of the term is 沙羅佉. Is it possible that 沙 is a mistake for 波, based on their structural similarity? Thus, the term maybe renders 波羅伽, Skt. palāśa, “carry over (to the other shore),” referring to the “boat” of pāramitā, alluding to the semantics of 波羅蜜; consequently, in the passage, the power of prajñāpāramitā (“perfection of wisdom”) might be invoked as protection against malicious spirits. Along these lines, a (speculative) translation of the passage would be the following: “Baku (Vakula) Demon of the Eastern deep mountains, [you should not harm the residents; otherwise, with] the power of the Perfection of Wisdom, [I] will restrain you hundred spirits by attaching a cangue to your necks!” |

| 54 | Again, there is a direct parallel to this spell in the Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng:

In a Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng fragment preserved at the Joraku-an depository of Tōfuku-ji 東福寺常楽庵 in Kyōto, there is an even-closer match of the phrase 佉收汝 with our text, 伽収汝: (龍王□〔仂ヵ〕・宅西方□〔大ヵ〕・伽収汝□〔百ヵ〕・婆□・□・□・若□〔有ヵ〕・二足□; see https://mokkanko.nabunken.go.jp/ja/MK026035000001; consulted 4 July 2022). |

| 55 | Reconstructions are based on (Pulleyblank 1991). Interestingly, there seems to be no differentiation between final -n and -ŋ, which could point to a northwestern medieval Chinese origin of this stanza. |

| 56 | 與圊 is parallel to 池沼 and thus should be interpreted as a noun. Most likely, the 與 is a phonetic loan for 浴 (> “bath and privy”). In the verse below, shènglíng 聖靈 is an unusual expression, and we read shénlíng 神靈. 聖靈 usually refers to the spirits of the deceased, a meaning that does not fit here. |

| 57 | Míngdēng 明燈 means “bright lamp,” a metaphor for the wisdom of the Buddha. |

| 58 | Wǔyǎn 五眼 means “five eyes” (physical eye, heavenly eye, eye of wisdom, Dharma eye, and Buddha eye). This term appears extremely frequently in prājñapāramitā literature, often in combination with liù shéntōng 六神通 “six supernatural abilities.” |

| 59 | Suì yuè jiéshā 歲月劫殺 might refer to the suìshā 歲殺 and jiéshā 劫殺, two traditional Chinese calendric spirits. Compare the Shén shū jīng, where it is stated that their Yīn vapors/energies (隂氣) are poisonous (神樞經: “嵗殺者,隂氣尤毒謂之殺也。常居四季謂四季之隂氣能遊天上。”; Yùdìng xīnglì kǎoyuán 御定星曆考源, fascicle 2: 32; ““劫殺者,嵗之隂氣也。主有殺害,所理之方忌有興造,犯之主有劫盜傷殺之事。”; Yùdìng xīnglì kǎoyuán 御定星曆考源, fascicle 2: 33). In the case of the latter, if an owner of a residence initiates building activities during taboo periods, inauspicious happenings such as robbery, injury, and murder will occur. |

| 60 | Here, the residence of a person is equated with the sanctuary of the Buddha. |

| 61 | The formula 頭破作七分 frequently appears at the end of sūtras, when Buddha utters a warning concerning improper behavior or actions against the Buddhist teachings or regulations. Compare T. 1, No. 33, p. 817c28–818a2 (Héngshuǐ jīng 恒水經): “From that time onward, the Buddha did not teach anymore the prohibitions of the sūtras. The prohibitions of the sūtras are very grave, and if there should be anybody in the assembly who offends against the prohibitions, his head will be torn into seven pieces. The Buddha concluded the teaching of the sūtra. All disciples single-mindedly maintained the Vinaya regulations” (自今已後,佛不復說經戒。佛經戒甚重,中有受持戒犯惡者,頭破作七分故也。佛說經訖。諸弟子皆一心重持戒法。). The following is another example: “Based on the divine power of this dharānī, if there are human or nonhumans (i.e., all kinds of spiritual beings) belonging to the Māra family, then their heads will be crushed into seven pieces” 以此陀羅尼威神力故,若魔眷屬人非人等頭破作七分。 (T. 13, No. 402, p. 567b26; Bǎoxīng tuóluóní jīng 寶星陀羅尼經; [Mahāsaṃnipāta]ratnaketu dhāraṇī). Even in the short scripture discussed in this paper, it is mentioned twice, emphasizing the divine power of the Buddha in the protection of one’s dwelling. If a spiritual being should ignore the Buddha’s command, then, by consequence, its head will be crushed into pieces. |

| 62 | In this passage here, the spirits/demons are directly addressed and confronted with the consequences of their naughty behavior. In canonical Buddhist texts, shuǐjiāng水漿 “broth/gruel” is occasionally used as an offering to the Buddha or a sagely person, indicating the basics one needs to nourish oneself and keep one’s body alive (as a combination of food and drink; however, in most texts, it is instead classified as a drink). Compare the Guāng zàn jīng 光讚經 (Skt. Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā sūtra): “Those who were blind from birth regained their eyesight and could see shapes; those who were deaf achieved hearing; those who were mentally deranged regained their wits, those who were naked received clothing; whose who were hungry managed to eat; and those who were thirsty got hold of gruel/broth” (其生盲者得目覩形,聾者逮聽,狂者復意,裸者獲衣,飢者致食,渴得水漿; T. 8, No. 222, p. 151a17–19). Běn gōng 本宮, lit. “original palace/mansion,” probably refers to the residence in which the spirits have settled; however, gōng can also refer to zodiacal mansions. Because most of the cited spirits are astral deities, Buddha might also threaten to remove them from their original zodiacal mansions as punishment for troubling residents. However, this is merely hypothetical. |

| 63 | According to the Lùnhéng 論衡 (p. 968), “popular beliefs” play an important role; e.g., extending one’s residence into a western direction can have inauspicious and catastrophic consequences, even resulting in the death of family members (俗有大諱四。一曰:諱西益宅。西益宅謂之不祥,不祥必有死亡。相懼以此,故世莫敢西益宅。防禁所從來者遠矣). In the Sòng dynasty Lèishuō 類説 (p.843), there is a section titled zhái bù jūchù 宅不居處 (lit. “residences not habitable”), which lists nine locations not suitable for building a residence (凡宅不居當街口處,不居古寺廟及祠社爐冶處,不居草木不生處,不居故軍營戰地,不居正當水流處,不居山衝處,不居大城門口處,不居對獄門處,不居百川口處。). |

| 64 | On this passage, see also (Shēnjiā Jīn 2007, p. 6). |

| 65 | No reference to shāqīng 砂青 was found. We interpret it as zēngqīng 曾青, a type of copper, following (Shēnjiā Jīn 2007). |

| 66 | On this passage, see also (Shēnjiā Jīn 2007, pp. 159–60). |

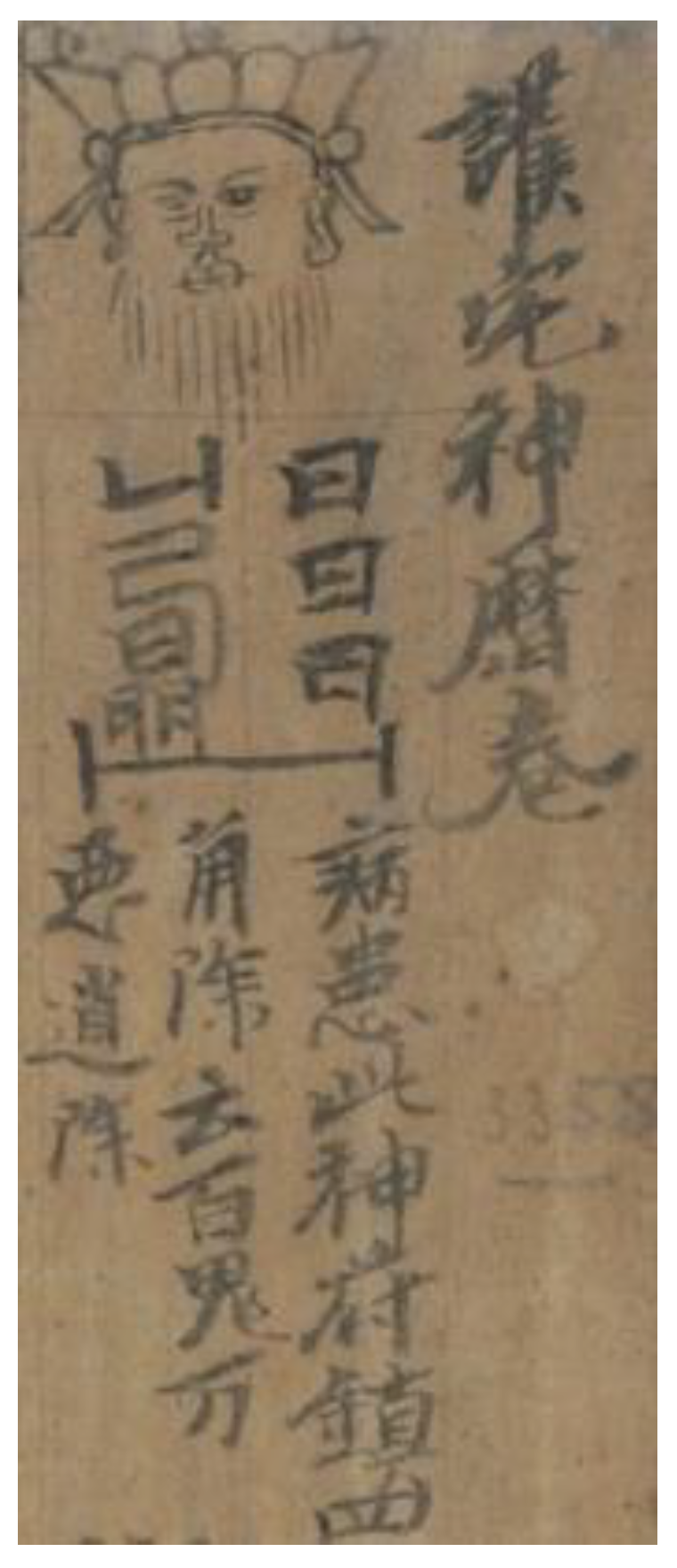

| 67 | The talismans are usually either pasted or buried at the four corners of a building to ensure its protection. For details, see (Zhōuhuī Yáo 2004, pp. 85–90). For a recent study on protective amulets and talismans, see (Líng Lǐ 2019). The fú discussed here is also mentioned in (Yu 2018). |

| 68 | Zhēdào fǎ遮道法, Skt. antarāyikā dharmāḥ. |

| 69 | On the transition of Buddhist monks living the life of itinerant monks to those settling in monastic structures in India, see (Daswani 2006). It is possible to date the beginning of this development to the 1st century BCE; see (Fogelin 2015, p. 104f). |

| 70 | Bùkōng juànsuǒ shénbiàn zhēnyán jīng 不空羂索神變眞言經 (Skt. Amoghapāśa-kalparāja), translated by Bodhiruci in 709. The rituals, dhāraṇīs, and maṇdalas in this text are especially related to manifestations of Alokiteśvara and Vairocana. |

| 71 | Jiāchí 加持, lit. “assistance, blessing” (DDB), refers to the performance of rituals or prayers for the purpose of connecting to a deity. In esoteric Buddhism, hùmó 護摩 (Skt. homa) refers to rituals involving the burning of objects (fire rituals); for details, see (Nakamura 1975, p. 386a). |

| 72 | Some of the master narratives in this respect are stories related to the submission of the demon deity Māra, his family, and his army. Instead of destroying them, Buddha ultimately converts them and turns them into protectors of Buddhism. |

| 73 | P.3519, leave 34, 1–3; compare (Juān Xióng 2015, p. 226). |

| 74 | This type of rhetoric against competitors in the medieval religious market is also typical of many other “apocryphal” Buddhist texts; for example, compare the Tiāndì bāyáng shénzhòu jīng 天地八陽神呪經, “Spell-sūtra of the Eight Principles of Heaven and Earth” (“愚人無智,信其邪師卜問望吉,而不修善、造種種惡業,命終之後復得人身者如指甲上土,墮於地獄、作畜餓鬼者如大地土。”) (T. 85, No. 2897, p. 1424a16-19). |

| 75 | See, for example, the Biàn zhèng lùn 辯正論, T. 52, No. 2110, p. 500a2-3. |

| 76 | The Dūnhuáng versions of the AZSZJ (and the differences to the “canonical” version) will be discussed in a forthcoming paper. |

References

Primary Sources and Collections

Bái zé jīngguài tú 白澤精怪圖 (Diagrams of Spectral Prodigies of White Marsh); P.2682.Bǎoxīng tuóluóní jīng 寶星陀羅尼經 (Skt. [Mahāsaṃnipāta]ratnaketu dhāraṇī); T. 13, No. 402.Biàn zhèng lùn 辯正論 (Discerning the Correct); T. 52, No. 2110.Biéyì zá āhán jīng 別譯雜阿含經 (Shorter Chinese Saṃyuktâgama); T. 2, No. 100.Bùkōng juànsuǒ shénbiàn zhēnyán jīng 不空羂索神變眞言經 (Infallible Lassoʼs Mantra and Supernatural Transformations: King of Ritual Manuals); T. 20, No. 1092.Cháng āhán jīng 長阿含經 (Skt. Dīrghâgama); T. 1, No.1.Chì Sōngzǐ zhānglì 赤松子章曆 (Almanac of Chì Sòngzǐ). In Dàozàng 道藏, Vol. 11.Chū sānzàng jìjí出三藏記集 (Almanac Compilation of Notes of the Translation of the Tripiṭaka); T. 55, No. 2145.Dàlóutàn jīng 大樓炭經 (Sūtra on the Great Conflagration); T. 1, No. 23.Dà-Táng xīyù jì 大唐西域記 (Record of Travels to the Western Regions); T. 51, No. 2087.Dà zhuāngyán lùnjīng 大莊嚴論經 (Skt. *Sūtrâlaṃkāra-śāstra); T.4, No. 201.Dàzhì dùlùn 大智度論 (Skt. Mahāprajñāpāramitā-śāstra); T. 25, No. 1509.Dàomén dìngzhì 道門定制 (Prescribed Rules for the Daoist Community); by Lǚ Yuánsù 呂元素; Dàozàng 道藏 Vol. 31.Dàomén kēfàn dàquánjí 道門科範大全集; by Dù Guāngtíng 杜光庭; Dàozàng 道藏 Vol. 31.Dàozàng 道藏. Běijīng: Wénwù chūbǎnshè 文物出版社; Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi shūdiàn 上海書店; Tiānjīn: Tiānjīn gǔjí chūbǎnshè 天津古籍出版社, 1988.Fǎjiè shèngfán shuǐlù shènghuì xiūzhāi yíguǐ 法界聖凡水陸勝會修齋儀軌 (Comprehensive Treatise on the Nature and Characteristics of the Dharmadhātu Holy and Wordly Water and Land Majestic Assembly); CBETA, X. 74, No. 1497.Fǎjù pìyù jīng 法句譬喻經 (Skt. Dharmapāda); T. 4, No. 211.Fāngguǎng dàzhuāngyán jīng方廣大莊嚴經 (Skt. Lalitavistara); T. 3, No. 187.Fó suǒ xíng zàn 佛所行讚 (Skt. Buddhacarita); T. 4, No. 192.(Fóshuō) ānzhái shénzhòu jīng (佛說)安宅呪經 (Sūtra (Spoken by the Buddha) of Magic Spells for Pacifying One’s Home); T. 21, No. 1394.Fóshuō guàndīng jīng 佛說灌頂經 (Consecration Sūtra Spoken by the Buddha); T. 21, No. 1331.Fóshuō què wēn huáng shénzhòu jīng 佛說却溫黃神呪經 (Sūtra of the Plague-Dispelling Incantation); CBETA, X. 2, No. 193.Fóshuō xīngqǐ xíng jīng 佛說興起行經 (The Sūtra on the Cause of Creation Spoken by the Buddha); T. 4, No. 197.Fóxīn jīng 佛心經 (Sūtra on the Buddha Mind); T. 19, No. 920.Gēnběn shuō yīqiè yǒubù Pínàiyè 根本說一切有部毘奈耶 (Skt. Mūla-sarvâstivāda-vinaya-vibhaṅga); T. 23, No. 1442.Gēnběn shuō yīqiè yǒubù Pínàiyè sòng 根本說一切有部毘奈耶頌 (Skt. Mūlasarvâstivāda-vinaya-kārikā); T. 24, No. 1459.Guāng zàn jīng 光讚經 (Skt. Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā); T. 8, No. 222.Guòqù xiànzài yīnguǒ jīng 過去現在因果經 (Scripture on Past and Present Causes and Effects); T. 3, No. 189.Héngshuǐ jīng 恒水經 (Sūtra of the Ganges River); T. 1, No. 33.Jīn guāngmíng zuìshèng wáng jīng 金光明最勝王經 (Skt. Suvarṇa-prabhāsôttamaḥ sūtrêndra-rājaḥ/Suvarṇa-bhāsôttamaḥ sūtrêndra-rājaḥ); T. 16, No. 665.Jìnshū 晉書 (The Book of the Jìn Dynasty), comp. by Fáng Xuánlíng 房玄齡 et al. (Táng Dyn.). Běijīng: Zhōnghuá shūjú 1974.Kǒngquè wáng zhòu jīng 孔雀王呪經 (The Sūtra of the Spell of the Peacock King); T. 19, No. 988.Lèishuō 類説 (Categorized Tales); comp. by Zēng Zào 曾慥 (Sòng dynasty); Yǐngyìn wényuāngé sìkù quánshū 影印文淵閣四庫全書, Vol. 873. Táiběi : Táiwān shāngwù yìnshūguǎn 臺灣商務印書館, 1986.Língbǎo lǐngjiào jǐdù jīnshū 靈寶領教濟度金書 (The Golden Book of Salvation According to the Língbǎo Tradition). In Dàozàng 道藏, Vol. 7.Liù chén zhù Wénxuǎn 六臣註文選 (Commentaries on the Six Masters on the Wénxuǎn), complied by Xiāo Tǒng 蕭統 (Liáng Dyn.) and commented on by Lǐ Shàn 李善 et al. Sìbù cóngkān 四部叢刊. Ed. Shànghǎi Hánfēn-lóu yǐngyìn Wǔyīng-diàn jùzhēn běn 上海涵芬樓影印武英殿聚珍本, 1929. Cè 冊 1901.Lùnhéng jiàoshì 論衡校釋 (An Annotated Edition of the Discussive Weighing); ed. by Huáng Huī 黃暉. Běijīng: Zhōnghuá shūjú 中華書局, 1990.Luóyún rěnrǔ jīng 羅云忍辱經; T. 14, No. 500.Móhē bōrě bōluómì jīng摩訶般若波羅蜜經 (Skt. Pañca-viṃśati-sāhasrikā-prajñā-pāramitā sūtra); T. 8, No. 223.Móhē sēngqí lǜ 摩訶僧祇律 (Skt. Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya); T. 22, No. 1425.Mù tiānzǐ zhuàn 穆天子傳 (Biography of King Mù). Mù tiānzǐ zhuàn huìjiào jíshì 穆天子傳匯校集釋, ed. by Wáng Yíliáng and Chén Jiànmǐn. Shànghǎi: Huádōng Shīfàn dàxué chūbǎnshè 華東師範大學出版社, 1994.Púsà běnshēng mán lùn 菩薩本生鬘論 (Skt. Jātaka-mālā); T. 3, No. 160.Pǔyào jīng 普曜經 (Skt. Lalitavistara); T. 3, No. 186.Qī Fó bā púsà suǒshuō dà tuóluóní shénzhòu 七佛八菩薩所說大陀羅尼神呪經 (Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī Spirit-Spells Spoken by the Seven Buddhas and Eight Bodhisattvas); T. 21, No. 1332.Róng zhāi suí bǐ 容齋隨筆 (Miscellaneous Notes from the Tolerant Studio). Ed. by Hóng Mài 洪邁. 1978. Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi gǔjí chūbǎnshè 上海古籍出版社.Ruíxìyē jīng 蕤呬耶經 (Skt. Guhya-sūtra); T. 18, No. 897.Sānfǔ huángtú 三輔黄圖 (Yellow [i.e., Imperial] Maps of the Three Metropolitan Areas); included in Yǐngyìnwén Yuāngé Sìkù quánshū影印文淵閣四庫全書 [The Complete Works in Four Sections of the Literary Abyss Library], cè 468. Táiběi: Táiwān Shāngwù yìshūguǎn, 1986.Shēng jīng 生經 (Jātaka-sūtra); T. 3, No. 154.Shì Móhēyǎn lùn 釋摩訶衍論 (Explanation of the Treatise on Mahāyāna); T. 32, No. 1668.Shǒuhù dàqiān guótǔ jīng 守護大千國土經 (Sūtra of Protecting the Great Thousand Lands; Skt. Mahāsāhasrapramardanī-nāma-mahāyānasūtra); T. 19, No. 999.Sìfēn lǜ 四分律 (Vinaya of the Four Categories; Skt. *Dharmaguptaka-vinaya); T. 22, No. 1428.Tàishàng jiǔtiān yánxiáng dí’è sìshèng miàojīng 太上九天延祥滌厄四聖妙經 (Ultimate High Miraculous Scripture of the Four Saints in the Nine Heavens Who Grant Good Fortune and Dispel Distress). In Dàozàng 道藏, Vol. 1.Tiān Lǎo shén guāng jīng 天老神光經 (The Scripture of the Divine Light of the Heavenly Lǎo[zǐ]); Dàozàng 道藏 Vol. 18.Tiānpǐn miàofǎ liánhuá jīng 添品妙法蓮華經 (Lotus sutra; Skt. Saddharmapuṇḍarīka sūtra); T. 9, No. 264.Tuóluóní zájí 陀羅尼雜集 (Skt. Maṇībhadra-dhāraṇī); T. 21, No. 1336.Wǔxíng dàyì 五行大義 (The Cardinal Meaning of the Five Phases), comp. by Xiāo Jí 蕭吉 (Suí Dyn.). In Xùxiū Sìkù quánshū 續修四庫全書 (Supplement to the Complete Books of the Four Storehouses), cè 冊 1060. Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi gǔjí chūbǎnshè, 2002.Xiǎopǐn bōrě bōluómì jīng小品般若波羅蜜經 (Shorter Version of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā sūtra); T. 8, No. 227.Xù gāosēng zhuàn 續高僧傳 (Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks); T. 50, No. 2060.Xùxiū Sìkù quánshū 續修四庫全書 (Supplement to the Complete Books of the Four Storehouses). Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi gǔjí chūbǎnshè 上海古籍出版社.Xùzàngjīng 續藏經 (Continuation of the Tripiṭaka). Táiběi: Táiwān xīnwénfēng chūbǎn gōngsī 台灣新文豐出版公司, 1993.Yīqiè jīng yīnyì 一切經音義 (Sound and Meaning of All Scriptures); T. 54, No. 2128.Yùpiān 玉篇 (Jade Book). In Yǐngyìn wényuāngé sìkù quánshū 影印文淵閣四庫全書, Vol. 224. Táiběi: Táiwān shāngwù yìnshūguǎn 臺灣商務印書館, 1986.Yúqié shī dìlùn 瑜伽師地論 (Skt. Yogâcārabhūmi-śāstra); T. 30, No. 1579.Zá āhán jīng 雜阿含經 (Skt. Saṃyuktâgama-sūtra); T. 2, No. 99.Zhèng yī jiào zhái yí 正一醮宅儀 (Correct Rituals for Residences). Dàozàng 道藏 Vol. 18.Secondary Sources

- Arrault, Alain. 2010. Activités médicales et méthodes hémérologiques dans les calendriers de Dunhuang du IXe au Xe siècle: Esprit humain (renshen) et esprit du jour (riyou). In Médicine, religion et société dans la Chine médiévale: Étude de manuscrits Chinois de Dunhuang et de Turfan. Edited by Catherine Despeux and Isabelle Ang. 3 vols. Paris: Collège de France, Institute des Hautes Études Chinoises, vol. 1, pp. 285–332. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr. 1990a. Introduction: Prolegomenon to the Study of Buddhist Apocryphal Scriptures. In Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha. Honolulu: University of Hawai´i Press, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr., ed. 1990b. Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha. Honolulu: University of Hawai´i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, Robert E., and Donald S. Lopez, eds. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cáo, Líng 曹凌. 2011. Zhōngguó fójiào yíwěi jīng zōnglù 中國佛教疑偽經綜錄 [A Comprehensive Catalogue of Chinese Buddhist Apocryphal Scriptures]. Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi gǔjí chūbǎnshè 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Chén, Yúzhù 陳于柱. 2007. Dūnhuáng xiěběn zháijīng jiàolù yánjiū 敦煌寫本宅經校錄研究 [A Critical Study of the Zhái jīng Dūnhuáng Versions]. Běijīng: Mínzú chūbǎnshè 民族出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Daswani, Rekha. 2006. Buddhist Monasteries and Monastic Life in Ancient India: From the Third Century BC to the Seventh Century AD. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton, Franklin. 1970. Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Enso, Kobayashi 小林圓照. 2009. Baishārī yakubyō kyūsai tan to Kyakuon’ō-jinju-kyō no hensei ヴァイシャーリー疫病救済譚と『却温黃神呪経』の編成 [The Vaiśali Plague Story and the Compilation of the Què wēnhuáng shénzhòu jīng]. Indogaku bukkyōgaku kenkyū 57: 1098–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelin, Lars. 2015. An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Donald, and Marc Kalinowski, eds. 2017. Books of Fate and Popular Culture in Early China: The Daybook Manuscripts of the Warring States, Qin, and Han. In Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, vol. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, Akira 平川彰, ed. 1997. A Buddhist Chinese-Sanskrit Dictionary 佛教漢梵大辭典. Tōkyō 東京: Reiyūkai 霊友会. [Google Scholar]

- Jīn, Shēnjiā 金身佳. 2007. Dūnhuáng xiěběn zháijīng zàngshū jiàozhù 敦煌寫本宅經葬書校註 [Annotated Translations of Scriptures on Residences and Texts on Burial Sites among the Dūnhuáng Manuscripts]. Běijīng: Mínzú chūbǎnshè. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Stephen. 2010. In Search of the Folk Daoists of North China. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, Marc. 2017. Hemerology and Prediction in the Daybooks: Ideas and Practices. In Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 138–206. [Google Scholar]

- Keyworth, George A. 2016. Apocryphal Chinese Books in the Buddhist Canon at Matsuo Shintō Shrine. Studies in Chinese Religions 2: 281–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Li-Ying. 2000. Sur les apocryphes bouddhiques chinois. Bulletin de l’École française d’Exrême-Orient 87: 677–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋靜志. 2020. Sān bù Záāhán jīng (Dàzhèngzàng 99, 100, 101) Yuányǔ wèntí jí qí suǒshǔ bùpài zhī kǎo 三部《雜阿含經》 (《大正藏》99、100、101) 原語問題及其所屬部派之考 [A study of the problems of the source language and sectarian affiliation of the three-part Zá āhán jīng (Saṃyuktâgama-sūtra), Taishō nos. 99, 100, 101]. Fóguāng xuébào 佛光學報 6: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kósa, Gábor. 2013. Buddhist Monsters in the Chinese Manichaean ‘Hymnscroll’ and the Guanyin Chapter of the ‘Lotus Sutra’. The Eastern Buddhist 44: 27–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lǐ, Líng 李零. 2019. Zhōngguó fāngshù kǎo 中國方術考 [A study of Divination in China]. Běijīng: Zhōnghuá shūjú 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Lexian. 2017. Daybooks: A Type of Popular Hemerological Manual of the Warring States, Qin, and Han. In Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Boying. 2019. History of Medicine in Chinese Culture. 2 vols. Hackensack: World Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Makita, Tairyō 牧田諦亮. 1976. Gikyō kenkyū 疑經研究 [Research in “Doubtful” sūtras]. Tokyo: Tōkyo daigaku jinbun kagaku kenkyūjo 京都大學人文科學研究所. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Daniel Patrick. 2016. The Planetary Visibility Tables in the Second-Century BC Manuscript Wu xing zhan 五星占. HAL 43: 17–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Hajime 中村元. 1975. Bukkyōgo daijiten 佛教語大辞典 [An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Buddhist Terms]. 2 vols. Tokyo: Tōkyō shoseki kan 東京書籍刊. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao, Takashi 中尾堯. 1996. Myōrenjizō “Matsuosha issaikyō” no hakken to chōsa 妙蓮寺蔵「松尾社一切経」の発見と調査 [Investigation of the Discovery of the Matsuo Shrine [Buddhist] Canon, held by the [Sūtra] Repository of Myōren Temple]. Rissho daigaku bungakubu ronsō 立正大学文学部論叢 103: 109–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nakao, Takashi 中尾堯, and Honmon Hokkeshū Daihonzan Myōrenji 本門法華宗大本山妙蓮寺, eds. 1997. Kyōto Myōrenji zō “Matsuosha issaikyō” chōsa hōkokusho 京都妙蓮寺蔵「松尾社一切経」調査報告書 [Written Report Investigating the Matsuo Shrine [Buddhist] Canon, Held by Myōren Temple in Kyoto]. Tokyo: Ōtsuka kōgeisha 大塚巧藝社. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, Toshinori, Antonino Forte, Tairyō Makita, and Silvio Vita. 1991. The Manuscripts of Nanatsu-dera: A Recently Discovered Treasure-house in Downtown Nagoya. Kyoto: Istituto italiano di cultura Scuola di studi sull’Asia orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1991. Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shǐ, Jīngpéng 史經鵬. 2016. Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng zhěnglǐ yǔ yánjiū <安宅神咒經>整理與研究 [A collation and study of the Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng]. In Fójiào wénxiàn yánjiū 收入方廣錩主編《佛教文獻研究》]. Edited by Fāng Guǎngchāng 方廣錩. Guìlín 桂林: Guǎngxī shīfàn dàxué chūbǎnshè 廣西師範大學出版社, pp. 155–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Richard. 2017. The Legacy of Daybooks in Late Imperial and Modern China. In Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 336–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tokuno, Kyoko. 1990. The Evaluation of Indigenous Scriptures in Chinese Buddhist Bibliographical Catalogues. In Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha. Honolulu: University of Hawai´i Press, pp. 31–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wáng, Zǐjīn 王子今. 2003. Shuìhǔdì Qínjiǎn Rìshū jiǎzhǒng shūzhèng 睡虎地秦簡《日書》甲種疏證 [Annotated Edition of the Qíng Dynasty Shuìhǔdì Day Book]. Wǔhàn 武漢: Húběi jiàoyù chūbǎnshè 湖北教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Xiāo, Dēngfú 蕭登福. 2003. Dàojiā dàojiào yǔ zhōngtǔ fójiào chūqī jīngyì fāzhǎn 道家道教與中土佛教初期經義發展 [The Development of the Meaning of Sūtras in Daoism and in the Early Period of Chinese Buddhism]. Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi gǔjí chūbǎnshè 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Xióng, Juān 熊娟. 2015. Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng yǔliào jiànbié 《安宅神咒經》語料鑑別 [A differentiation of the corpus of Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng scriptures]. In Hànwén fódiǎn yíwěi jīng yánjiū 《漢文佛典疑偽經研究》 [Studies in Chinese Buddhist Apocryphal Scriptures]. Shànghǎi: Shànghǎi gǔjí chūbǎnshè 上海古籍出版社, pp. 222–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yáo, Zhōuhuī 姚周輝. 2004. Shénmì de fúlù zhòuyǔ 神秘的符籙咒語 [Magical Mantras and Talismans]. Nánníng 南寧: Guǎngxī rénmín chūbǎnshè 廣西人民出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xin, ed. 2018. Rituels d’exorcisme à partir de figurines magiques trouvées le long de la route de la soie. In Savoirs traditionelles et pratiques magiques sur la route de la soie. Paris: Demopolis, pp. 442–506. [Google Scholar]

- Zhāng, Qímíng 張齊明. 2011. Foshuo Ānzhái shénzhòu jīng suǒ jiàn ānzhái guānniàn jí qí yǐngxiǎng 《佛說安宅神咒經》 所見安宅觀念及其影響 [The concept and influence of ‘pacifying one’s home’ in the Ānzhāi shénzhòu jīng]. Zōngjiàoxué yánjiū 宗教學研究 3: 83–88. [Google Scholar]

| Scripture Title ⇒ Catalogue ⇓ | 七佛安宅神呪[經] | 安宅呪[法] | [佛說]安宅神呪[經]6 | 安宅經 | ||||

| 真偽 | 存失 | 真偽 | 存失 | 真偽 | 存失 | 真偽 | 存失 | |

| 出三藏記集 | 真 | 存 | 真 | 存 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (法經)眾經目錄 | 真 | 失 | -- | -- | 偽 | 存 | 偽 | 存 |

| 歷代三寶記 | 真 | 失 | 真 | 失 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 大唐內典錄 | 真 | 失 | 真 | 失 | 偽 | 存 | 偽 | 存 |

| 大周刊定眾經目錄 | 真 | 失 | -- | -- | 真 | 存 | 偽 | 存 |

| 開元釋教錄 | 真 | 失 | 真 | 存 | 真 | 存 | 偽 | 存 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, G.; Anderl, C. How to Protect One’s Home in Medieval China? A Study of the Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng 佛說安宅神呪經. Religions 2023, 14, 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030368

Yang G, Anderl C. How to Protect One’s Home in Medieval China? A Study of the Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng 佛說安宅神呪經. Religions. 2023; 14(3):368. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030368

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Gang, and Christoph Anderl. 2023. "How to Protect One’s Home in Medieval China? A Study of the Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng 佛說安宅神呪經" Religions 14, no. 3: 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030368

APA StyleYang, G., & Anderl, C. (2023). How to Protect One’s Home in Medieval China? A Study of the Fóshuō ānzhái shénzhòu jīng 佛說安宅神呪經. Religions, 14(3), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030368