Abstract

In 1977, a diverse group of forty-five leaders and scholars drafted the “Chicago Call”, urging evangelicals to reconnect with historic Christianity and embrace a richer understanding of worship and sacrament. The Call highlighted tensions between those who understood evangelicalism as a movement within the broader Church and those who prioritized Reformation principles and scriptural authority. This article begins by exploring the origins of the conference, key leaders, and its historical context. It then moves to a comparison of primary documents, revealing points of friction that arose between conference participants as they worked to draft the statement. I conclude by assessing the Chicago Call’s limitations, emphasizing the inherent fragility of the evangelical coalition and the ongoing challenge of negotiating a theological consensus.

Keywords:

Chicago call; Robert Webber; evangelicalism; Bible; sacraments; historical continuity; unity; identity 1. Introduction

What does it mean to be an “evangelical”? This question has become particularly vexing in the aftermath of the 2016 American presidential election, when a group of people identified by the media as “evangelicals” played an outsized role in electing a controversial president. Different camps within this constituency responded to Donald Trump’s presidency in different ways: some with shouts of affirmation, others with cries of anguish, and many wondering publicly and privately whether they want to claim the label “evangelical”. Indeed, Trump’s rise to political power coincided with a raft of scholarship around definitional questions, including books with on-the-nose titles like Who is an Evangelical? The History of a Movement in Crisis (2019) and Evangelicals: Who They Have Been, Are Now, and Could Be (2019). Today, the word “evangelical” has become a shibboleth, presumed to reveal as much about an individual’s political identity as it does about his or her theology.

However, the question “Who is an evangelical?” goes back further than 2016. Forty years earlier, Newsweek featured a cover story, written by religion editor Kenneth Woodward, about what the magazine famously described as “the year of the evangelical”. At the time, Jimmy Carter, a self-described evangelical who spoke publicly about his faith on the campaign trail, had unexpectedly captured the American presidency. Woodward noted that the moment was fraught for conservative Protestants. “Just as the nation is at last taking notice of their strength, evangelicals find their house divided”, he observed. “The Presidential election has only exacerbated latent differences in doctrine and social attitude”. Woodward concluded with a sobering prediction: “[This] may yet turn out to be the year that evangelicals won the White House but lost cohesiveness as a distinct force in American religion and culture” (Woodward 1976, p. 78).

I juxtapose these two presidential elections for their similarities: both show that divisive American socio-political conflicts often exacerbate equally deep conflicts amongst evangelicals over their definitional identity. However, there are also significant differences between the 1976 and 2016 evangelical landscapes. When cultural commentators today explain twenty-first century intra-evangelical conflicts, they tend to downplay the role of theology. “Evangelical leaders often like to claim that evangelicalism is defined not by race or by politics but by theology”, suggests historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez. “Yet, in reality, political and social issues tend to define evangelical identity every bit as much as theological claims—perhaps even more so” (Stewart 2024). Similarly, when commenting on the fractured state of contemporary evangelicalism, former Fuller Theological Seminary president Mark Labberton observes,

Evangelicals can affirm that faith commitments and their implications are essential to discerning values; but when evangelicals who affirm the same baseline of faith reach radically opposing social and political opinions, we have to ask what else is at play. The collusion can’t be explained by different definitions of the incarnation or by alternate views of the Bible and its authority. Rather, opposing views expose that underneath “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” lie basic instincts in our mental and social frames related to who and what actually matters.(Labberton 2018, p. 6)

By contrast, Woodward’s 1976 Newsweek story highlighted specifically theological ruptures within the evangelical movement:

Evangelicals are sharply divided over fundamental religious issues such as the infallibility of Scripture and what they think the Gospel requires of them as born-again Christians. Searching for more authentic Christian lifestyles, younger evangelicals are rejecting the salvation-brings-success ethos of establishment evangelicals. And in their hour of political ascendancy, the evangelicals are exhibiting new and often sharply divergent views on how the church should relate to public affairs.(Woodward 1976, p. 70)

For at least one group of influential Christians, the most significant threat to evangelical identity in the late 1970s came from inside the Church. Deeply concerned about what they perceived as the rootlessness, individualism, and superficiality of their movement, these leaders gathered together to make an appeal to fellow American evangelicals for recovering a more historically grounded understanding of the Christian faith. This article offers an in-depth analysis of their conference, the theological debates it raised, and the statement it produced: the Chicago Call of 1977. It shows that even as “evangelical” identity was becoming important in American political life, evangelicals continued to debate foundational questions about their religious identity.

The idea for the Call originated with Robert Webber, a forty-four-year-old professor of church history at Wheaton College, Illinois. Webber was an interesting figure. Born in the Congo to missionary parents, he was raised in a Baptist church in Philadelphia and earned an undergraduate degree from Bob Jones University. Over the course of his graduate education, he earned degrees at Anglican, Presbyterian, and Lutheran seminaries. He began teaching at Wheaton College in 1968, where he was described as “youthful, energetic and sympathetic to the concerns of students … a popular and highly effective lecturer” (Webber 2012). In the 1970s, Webber became increasingly convinced that the evangelical church had tossed aside vital worship practices during the Reformation, and that the spiritual health of contemporary evangelicalism depended upon a recovery of a “catholic” concept of the Church.

Webber contacted several like-minded colleagues, and in May 1977, they hosted a two-day conference at a retreat center ten minutes away from Wheaton. The forty-five participants came from Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist, Free Church, and Roman Catholic traditions and shared a common goal: to draft an appeal urging evangelicals to return to the theology and practices of historic Christianity. Attendees were divided into eight working groups, each tasked with drafting one section of the statement. Over the course of two days, the group produced a five-page document titled “The Chicago Call: An Appeal to Evangelicals”, which included eight sections: a call to historic roots and continuity, a call to biblical fidelity, a call to creedal identity, a call to holistic salvation, a call to sacramental integrity, a call to spirituality, a call to church authority, and a call to church unity. In the end, all but three participants signed the final statement.

The Chicago Call was printed in the popular magazine Christianity Today (Tinder 1977) and then published, along with explanatory essays, as The Orthodox Evangelicals in 1978 (Webber and Bloesch 1978). It also received national media attention: Ken Woodward, the religion editor who wrote the Newsweek cover story about the “year of the evangelical” in 1976 covered the Chicago Call conference for that same publication in 1977. In post-conference interviews, Webber was enthusiastic about what the group of theologically diverse leaders had accomplished. “I am not surprised that the Call contains differences”, he explained. “What amazes me is that there were not more! I am encouraged by the unanimity that did exist among us and look on the Call as a beginning” (Read et al. 1979, p. 10). Other conference participants were more reserved in their assessment. One attendee conceded that the Call represented a compromise in which “everyone lost something in the final struggles over the wording” (Viviano 1978, p. 228). Another expressed doubt that “anyone present who endorsed the Chicago Call was wholly happy with every one of the eight affirmations it asks other evangelicals to consider” (Daane 1977, p. 2).

Two groups emerged early in the Chicago Call conference. On one side were the conference organizers and their like-minded colleagues. They saw evangelicalism as a renewal movement within the larger Church and believed that contemporary evangelicalism could be revitalized by embracing overlooked aspects of the Church’s common catholic heritage, especially from the first three centuries. However, liturgical historian Paul Bradshaw identified a problem with attempts to ground unity in a “return” to the practices of the early church: namely, what to do with the radical discontinuities in practice introduced during the sixteenth century? As Bradshaw puts it, “efforts to find ‘deep structures’ that perdure throughout all forms of Christian worship typically founder on these [Reformation] rocks”(Bradshaw 1998, p. 185). Bradshaw’s insight foreshadows the concerns of a second group of conference participants with a more populist understanding of evangelicalism: one that emphasized the necessity of the Reformation and aligned with the dominant beliefs taught at Wheaton College, championed by Billy Graham, and defended by publications like Christianity Today. This group valued church tradition, but their priority was to uphold the authority of scripture. These competing understandings of evangelical Christianity sat uneasily side by side, vying for supremacy during the conference and after. The Chicago Call may have been an imperfect compromise, but it provides an excellent case study in the challenges of conducting theological dialogue within an evangelical tradition that remains deeply divided today.

2. Methods

In what follows, I will draw on unpublished primary source materials from Evangelism and Missions Archives of Wheaton College, Illinois, to analyze the internal theological debates that produced the Chicago Call statement. The Wheaton collection houses all existing records of the conference, including correspondence, detailed minutes of the nine conference planning meetings, two sets of notes (written by two different hands) that record specific comments made during plenary discussions, and drafts of each section of the Chicago Call.

This article will proceed in three stages. The next section explains how the conference originated, introduces key leaders, and situates the event in its historical context. The minutes from the nine conference planning sessions reveal several important details. For instance, the conference was organized swiftly to avoid clashing with two other national evangelical gatherings. The first round of invitations was sent out less than three months before the event: as a result, more than half of the planning committee’s preferred candidates were unable to attend.

Where exactly were the points of friction that arose among these particular evangelicals as they worked to draft a consensus statement? To date, nothing in the robust field of the secondary literature about the Chicago Call has addressed this question directly.1 Webber himself offers only a passing reference to controversies in his behind-the-scenes account of the conference proceedings:

In a plenary session we all went through the entire draft word for word. The main contention throughout the day was between those who desired a more catholic expression and those who wanted to retain a language more common to the Reformers. This issue became particularly evident in “A Call to Sacramental Integrity” which was sent back for re-write before approval. The conferees were in good spirits throughout the day evidencing a real sense of seeking to understand the other point of view.(Webber 1978, pp. 31–32)

The primary documents provide many more clues about the specifics of the conferees’ disagreements. In particular, four sections of the Call—the Prologue, the “Call to Historic Roots and Continuity”, the “Call to Biblical Fidelity”, and the “Call to Sacramental Integrity”—went through several rounds of revisions. The task of the “Conference Debates” section is to analyze the marginal notes, deletions, and insertions of the primary source materials to show how the group’s collective thinking shifted and evolved.

The final segment concludes by taking stock of the achievements and limitations of the conference and its statement. The Chicago Call was a milestone attempt to consolidate evangelicalism behind a solid theological show of unity. However, behind-the-scenes debates reveal the inherent fragility of this alliance. The prescient question raised by the Chicago Call has only become more urgent today: can self-identified evangelicals negotiate the essential and nonessential elements of their faith without causing their coalition to collapse under the weight of internal disputes?

3. Conference Background and Planning

3.1. Assembling the Planners

Robert Webber, the primary architect of the Chicago Call, had a keen interest in the history and practices of the early church. Webber writes that he was first introduced to the writings of the “Apostolic Fathers” (a group of early Christian leaders and authors who lived shortly after the apostles) as a graduate student at Concordia Theology Seminary in St Louis in 1965:

To my surprise the study of these fathers revolutionized my thinking. … I had blindly assumed that my own brand of Christianity was clearly apostolic. But when I saw what the apostolic fathers thought, I began to realize that my own faith and practice was not exactly in tune with that of the second century.(Webber 1978, p. 21)

Webber started his graduate work with the intent of pursuing a doctorate in New Testament studies. Sensing his fascination with the early church, one of his professors pulled him aside and gave Webber a life-changing piece of advice: “If evangelicalism is to mature, she is going to have to develop an interest in history and this will come from trained historical theologians teaching in evangelical seminaries” (Webber 1978, p. 21). Evangelicals already had numerous scholars in the area of New Testament, he continued, but almost none in the area of historical theology. Webber switched tracks and eventually completed a doctoral thesis in historical theology.

As a teacher, Webber passed along his passion for the Church Fathers to his college students: “I noticed the immense interest they took in the fathers when I spoke about them in class. It was significantly more than a casual interest” (Webber 1978, p. 21). At the same time, Webber was growing increasingly concerned about the state of evangelical Christianity: “We are, for the most part, a people without roots…Most of us have no sense of the past, no understanding of where we came from, what our original concerns were”. He admonished, “We tend toward a superficiality, a pop-evangelicalism that markets Christ in the mass media [as] the cure for all ills” while at the same time denying “what God can do and does in the church and by the sacraments” (Webber 1978, p. 36). Before his death in 2007, Webber would go on to publish over thirty volumes on the subject of worship. He coined the term “ancient-future” to describe his vision for the recovery of church tradition among evangelicals, and for many Christians in low-church traditions, his work was their first introduction to the fruits of the Liturgical Movement.

In many ways, the Chicago Call marked the beginning of Webber’s ancient-future campaign. In November of 1976, Webber reached out to three like-minded scholars—Peter Gillquist, Thomas Howard, and Donald Bloesch—to ask for their help in planning a conference that would call evangelicals back to historic Christianity. (Webber’s intended title for the event was “National Conference of Evangelicals for Historic Christianity”). This trio of colleagues would have been sympathetic to Webber’s desire for reform. Gillquist pursued graduate studies at Dallas Theological Seminary and Wheaton College and worked full time for the evangelical organization Campus Crusade for Christ. At the time of the Chicago Call, he was an editor for the Thomas Nelson Publishing.2 During his time working for Campus Crusade, Gillquist began studying church history and came to the conclusion that the Orthodox Church was the only unchanged church in history. While he was collaborating with Webber, Gillquist was also working to establish a network of house churches called the New Covenant Apostolic Order that aimed to restore a primitive form of Christianity based in the writings of the early Church Fathers. In 1987, ten years after the Chicago Call, Gillquist would be instrumental in leading 2000 formerly Protestant Christians into canonical Orthodoxy.3

Thomas Howard had been raised in an influential evangelical family.4 He attended Wheaton College and became an Episcopalian in his mid-twenties. At the time of the Chicago Call, Howard was an English professor at Gordon College, where he known as “a tweedy professor who loved all things Oxford and attracted a loyal retinue of students” (Silliman 2020). He was an early expert on C.S. Lewis (whom he had met in 1961) and a specialist in T.S. Eliot’s religious poetry. After the Chicago Call, Howard would become a center of great interest in the evangelical world when in 1985, he entered the Catholic Church in 1985—a decision that cost him his position at Gordon—and when he brought out his religious memoir, Evangelical Is Not Enough, published that same year. In the book, Howard offered a defense of liturgy and church traditions including written prayers, the church calendar, the sacramental understanding of Communion, and the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Unlike the others, Donald Bloesch had not attended a conservative Christian college. His ecclesial roots were in the German Evangelical and Reformed Synod that merged into the United Church of Christ (UCC). He earned his undergraduate degree Elmhurst College (UCC) and completed his graduate work at Chicago Theological Seminary and then the University of Chicago. Bloesch did postdoctoral work in the field of systematic theology at Oxford, Basel, and Tübingen, and he became one of the most important evangelical interpreters of Karl Barth. Bloesch remained in the UCC denomination his entire life and spent his thirty-five-year career teaching at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary in Iowa. Bloesch described himself as a “catholic evangelical” and criticized the excesses of both the theological left and right.

Gillquist, Howard, and Bloesch had seniority and experience. However, they lived outside of the Chicago area, and Webber soon realized that he would need input from local individuals with more flexible schedules. To this end, he invited a small cadre of individuals from his church to join the planning team: Lane Dennis (a doctoral student at Northwestern University), his brother Jan Dennis of Lithocolor Press; Gerald Erickson, professor of English at Trinity College, Victor Oliver, editor-in-chief of Tyndale House, and Richard Holt, a dentist in Wheaton (Webber 1978, p. 24).5

3.2. Setting a Date

When Webber invited Bloesch, Gillquist, and Howard to join the planning committee, he suggested that the conference would be convened in the fall of 1977—a date almost a year away. However, the notes from the group’s first planning meeting (4 December 1976) noted two potential conflicts:

Bob Webber told of two forthcoming conferences, one with Armerding and Billy Graham next Fall—to bring unity and peace to the evangelical world. The second conference, also next Fall or earlier, to bring together all camps—funded by Fuller—conference on scripture. A question: what significance would these two conferences have on ours?

No further details are provided in the notes, but it is possible to make educated guesses about the conferences to which Webber was referring. In the 17 December 1976 issue of Christianity Today, there was an announcement that the evangelist Billy Graham, along with Wheaton College president Hudson Armerding and Donald Hoke (director of Wheaton’s Billy Graham Center) would be gathering in March with twenty-five other evangelical leaders to discuss the idea of convening a conference for a larger group. The goal of this conference would be “to unite evangelicals in developing strategy to meet the needs and opportunities facing the church in the next two decades”(Editor 1976).6 There are no public records of a Fuller-sponsored conference on scripture in the late 1970s. However, in September 1977, a group of some 50 theologians and Christian leaders met at the Chicago O’Hare Hilton to form an Advisory Board for the newly established International Council of Biblical Inerrancy and to prepare for a conference that would launch their group’s work in October 1978.7 It is entirely plausible that Webber had gotten wind of both events.

This abundance of conferences suggests that evangelicalism was at a critical juncture in the late 1970s. The precise origins of the movement are controversial, but many historians trace the beginnings of neo-evangelicalism (later shortened simply to “evangelicalism”) to the postwar coalition of conservative Protestants who separated from fundamentalism and founded the National Association of Evangelicals (1942), Fuller Seminary (1947), and Christianity Today (1956). The 1970s represented a period of transition from first generation leaders to a younger generation that sought more depth and less simple reaction to the liberal Protestants against whom the early generation positioned itself. Webber was at pains to stress both continuity and difference when he described the ethos that motivated the Chicago Call:

In the past ten years or so, a number of evangelicals have been growing beyond the borders of what has, until now, been regarded as the limits of evangelicalism. In the same way that our current evangelical fathers Billy Graham, Harold Ockenga, Harold Lindsell, Carl F.H. Henry and others grew beyond the borders of fundamentalism, so we, following their example, have continued to look beyond present limitations toward a more inclusive and ultimately more historic Christianity.(Webber 1978, p. 20)

The race was on to see which younger leaders would be able to unite the increasingly fractured movement and bring clarity and definition to the term “evangelical”. To that end, Webber strategized to get ahead of the other two conferences looming on the horizon.8 Consequently, the Chicago Call planning was incredibly rushed. The committee met nine times within two months—once, sometimes twice, a week and often at unusual times (early morning breakfast, Saturday afternoons, and after church services on Sunday). Meetings were convened during the holiday season, including the two days immediately following Christmas and the day after New Year’s.9 The date for the conference was a constantly moving target and was not finalized as 2–3 May 1977, until the eighth, penultimate meeting.

3.3. Selecting Participants

After the conference agenda was settled, the remaining piece of the puzzle was to finalize the invitation list. During the first, second, and third meetings, the executive committee debated the merits of an Advisory Board: a select group of individuals who could amplify the Call through their name recognition, established platforms, and networks of influence. Some of the names the committee brainstormed included Robert Schaper (dean of chapel at Fuller Theological Seminary), Bruce Lockerbie (The Stony Brook School), and C.T. MacIntyre (Institute for Christian Studies). Because an Advisory Board would bring the additional benefit of more gender diversity, suggestions also included Elisabeth Elliott, Cheryl Forbes, Madeleine L’Engle, and “other women”.10 An invitation letter was drafted, but no list of names was ever finalized. When the date of the conference was moved up to the spring, it seems the idea was dropped. Minutes from the fourth planning meeting simply state, “no time for advisors”.

Much of the time in the remaining meetings was spent drawing up names of potential conference attendees. The members of the planning committee each submitted their individual recommendations, and the list was then collaboratively winnowed and prioritized.11 The first group of names was decided upon during the sixth planning meeting. Of these, twenty appear to have been designated “high priority” invitees: they included individuals who had previously been considered for the Advisory Board, and people who had influence on both sides of the Atlantic (Some of the most recognizable names in this category included Dutch Catholic priest and professor Henri Nouwen, English-Canadian theologian J.I. Packer, and British pastor and theologian, John Stott).12 Additionally, three names on the prioritized list were doctoral students that members of the planning committee knew personally.13 Next were ten “second tier” invitees. These individuals had some name recognition, and almost all were college or seminary professors.14 At the seventh planning meeting, Peter Gillquist—who was late in submitting his recommendations—offered a list of ten additional names, which the committee accepted.15 At the eighth planning meeting, a “list of conferees” appears as an agenda item, but no further specifics are offered. At the ninth and final meeting, an official typed list of invitees appears for the first time. The list contains forty-eight names: twenty-one “top tier” names and ten “second tier” names first agreed upon by the entire group, the ten additional names suggested by Peter Gillquist, and seven new names.16

The rushed nature of conference planning had a ripple effect on everything that followed. The committee had settled on the conference date only one week prior to finalizing the invitation list. This meant that invitations to the early May conference were not mailed until late January or early February, leaving potential attendees less than three months to plan. Time constraints would have been particularly acute for invitees who lived abroad. For example, in a letter dated March 4th, John Stott wrote to Webber from London with his regrets: “Your kind letter of January 28 has only just reached me, for I have been constantly traveling”.

Further insights emerge by cross-referencing the names of the forty-eight original invitees against the names of the forty-eight individuals who ultimately attended the conference. Slightly over half of the original invitees declined the invitation (26 declined; 22 accepted). Of the committee’s original 21 “top tier” candidates, only six participated in the conference. (Three of those six were doctoral students).17 Thirteen of the conference attendees were invited at the last minute: some with less than two months’ notice.18

This background context helps bring two elements of the conference into sharper focus. First is the matter of geography. Historian Elesha Coffman has drawn attention to the fact that the Chicago Call was a particularly local effort:

Not everyone involved [in the Chicago Call] was [from Wheaton]. Signatories also represented Bethel, up in St. Paul, Minnesota; Fuller, out in California; Gordon-Conwell, in Boston; and Dubuque Seminary, in Iowa; along with a few other places. Mostly, though, their institutions were all places even a Wheaton College student without a car could easily access: the college itself, Tyndale House, Good News Publishers, College Church. With a little help from public transit, I could get to Elmhurst, North Park Seminary, and Trinity International University, too. I don’t want to press this point too hard, and I don’t want to be reductionistic, but viewing this geography as a historian and, even more so, from my other academic discipline—religious studies—I have to say that Wheaton is exactly the place you’d expect to find a youthful religious rebellion turning toward history and the high church.(Coffman 2012, pp. 111–12)

Coffman explains that from a sociological perspective, higher education tends to propel people toward “higher” churches. She concludes,

One need not cast the members of The Chicago Call group as crass social climbers in order to observe that, while their statement was in many ways countercultural, they did not entirely swim against the sociological tide. Many of them were already well-educated, suburban Presbyterians (and members of other churches in the Reformed wing of evangelicalism) in 1977. Ecclesially speaking, they had nowhere to go but up.(Coffman 2012, p. 112)

Such insights into the spiritual, cultural, and socio-economic context of Wheaton in the late 1970s add significant nuance to our understanding of the Call. A surprising number of evangelicals in the area were indeed migrating to Anglicanism during this period (See Noll 1978). At the same time, it is important not to overlook the most straightforward explanation for why so many participants came from the Wheaton area: invitations were issued at the last minute, and those who lived nearby were the most likely to accept.19

The second thing the statistics reveal is the conference that the executive committee originally planned was significantly different from the conference that actually took place. The committee started out with lofty ambitions: they had envisioned an Advisory Board of evangelical celebrities and a Call issued by a group of internationally recognized scholars, pastors, and church leaders. Therefore, it must have stung when Christianity Today described the Call signatories as “an ad hoc group” of “comparatively unknown Christians” (Tinder 1977, p. 32). In a personal conversation with Webber, Harold Lindsell, editor of the magazine, similarly observed that the Call had been “put together by such a mixed bag” (Webber 1978, p. 33).

The theological make-up of the conference may also have been a surprise to Webber. Forty-five people participated in the conference.20 Of this group, thirty-two attendees—nine planning committee members and twenty-three individuals from the original invitation list—would have been “known entities”. They came from diverse denominational backgrounds but were invited because Webber was confident that they would support his ecumenical goals. That left 13 “wildcards”—late additions whose theological positions were less known to the conference organizers. As we will see, three of these “wildcards”—Donald Tinder (book editor, Christianity Today), Morris Inch (ordained Baptist minister, Chair of Department of Biblical, Religious, and Archaeological Studies at Wheaton College), and David Wells (Congregationalist minister, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School)—would shape the final version of Chicago Call in ways that Webber and the planning committee may not have anticipated.21

4. Conference Debates

4.1. Determining a Title

In his introduction to The Orthodox Evangelicals, Webber noted that the planning committee was united by a conviction that evangelical Christianity suffered from a reduction in historic faith and practice. He simultaneously stressed that the organizers’ overarching concern was “to offer something positive rather than to be mere critics of the evangelical movement”(Webber 1978, p. 24). However, the committee’s critiques of evangelicalism were stronger than Webber’s public-facing account let on. The notes from the third planning meeting are particularly illustrative. At the end of the meeting, Dick Holt, the group’s secretary, recorded a summary of how the conference organizers understood their mission: “Our statements should say, ‘You have left historic Christianity and lost the understanding of what you affirm, and we want to call you back and recover the understanding of what you are doing’”22. Holt’s use of second- and third-person language for evangelicalism (referring to “you” and “they”, rather than the first-person “we”) is revealing. In his public writings about the Chicago Call, Webber emphasized that conference organizers “felt we were speaking from inside the [evangelical] movement rather than from the outside” (Webber 1978, p. 24) The planning minutes reveal an opposite side to the coin. Holt’s summation concludes with a telling observation: “The irony is that we are with them and yet not with them”.

Webber, Gillquist, Howard, and Bloesch operated with a small “e” definition of evangelical: it was a renewal movement within the larger universal church throughout the ages. As Webber put it, “those who stand in the biblical tradition and preach [the] gospel are evangelical no matter what denomination they belong to—whether Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, one of the Protestant denominations, or any of the many churches that stand in the free church tradition” (Webber 2009, p. 50). In his comments in The New Oxford Review, a magazine that sought to bring together evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics, planning committee member Thomas Howard made the point more colloquially:

There is one sense in which it may be said of you, “Once an evangelical, always an evangelical”. That is, if I end up wearing a brocaded maniple and fiddleback chasuble, and singing the Latin Mass at a 17-foot altar pushed hard against the east wall (which will take a bit of doing, seeing as how I am a layman), I will nonetheless always have near the center of my vision and concerns the things that my early [evangelical] training taught me.(Read et al. 1979, p. 12)

Less than ten years after the Chicago Call conference, Howard did in fact join the Roman Catholic Church; even then, he continued to identify as an evangelical. In a 1985 interview with Christianity Today about his conversion, Howard insisted, “As a Catholic, I can lay claim to the ancient connotation of the word ‘evangelical’—namely, a man of the gospel, referring to the gospel, the evangelical councils, and so on” (Howard 1985). Howard conceded that those who defined evangelicalism primarily by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century movements in the Church of England, the free church movement, or the American revivalist phenomenon might place him outside the definitional boundary.

Indeed, most rank-and-file churchgoers in the late 1970s would not have defined the term evangelical in a way that included any Roman Catholics. The Call was written at a time when evangelicalism was associated with mass media evangelists such as Pat Robertson (who started in 1961), Jimmy Swaggart (1971), and Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker (1974). Hal Lindsay’s 1970 runaway bestseller, The Late Great Planet Earth (1970) connected contemporary politics with “end-time” prophecies to events in the Bible, particularly in the books of Daniel, Ezekiel, and Revelation. In hindsight, historian Elesha Coffman astutely observes that the Call was “pointing one way—toward the past, toward tradition, toward contemplation—at a moment when the strongest currents in evangelicalism were flowing the other way—toward an apocalyptic future [and] toward change in the presentation, though not the content, of the gospel” (Coffman 2012, pp. 118–19).

Conference participant Donald Tinder would have sensed this tension. In his role as book editor at Christianity Today, Tinder had his finger on the pulse of the northern, postwar evangelicals associated with his magazine. He spoke out against the proposed subtitle of the Call, which was “An Appeal to Evangelicals”. Tinder favored something more all-encompassing: “An Appeal to Christians”. Tinder’s concern was that most of the conference participants were not well known at the popular level. He worried that the average evangelical reader would wonder, “Who are these people trying to speak to us? Half of them aren’t evangelicals. This is a group outside of evangelicalism trying to tell us what to do”. In other words, readers would focus on the signatories rather than the issues the conference was trying to raise. Tinder preferred to leave the distracting term evangelical to the historians and simply address the Call to the “one flock”. Ultimately, the conferees unanimously approved the original subtitle—Webber made a convincing argument that “an appeal to Christians wouldn’t have the same bite as an appeal to evangelicals would”—but there was enough support for Tinder’s proposal that Webber was nervous (See R. E. Webber 1978, pp. 30–31). The question of evangelical identity would continue to haunt the Call discussions, most noticeably in debates over the tone of the Prologue.

4.2. Prologue

The Prologue was included in a packet of materials the participants received prior to the conference. In contrast to the eight subsections of the Call, which were collaboratively written in small groups during the two-day conference, the prologue had been prepared in advance by the executive committee. They likely anticipated that it would be adopted with minimal discussion. Early in the first day’s deliberations, there was a motion and a second to accept the prologue with only slight stylistic emendations.

However, Tinder spoke up. As one who worked in popular journalism, he cautioned the group that they needed to take special care before moving ahead: the prologue was the place where the Callers would gain or lose readers. Specifically, Tinder worried that the prologue as drafted gave the impression that the Callers thought the current state of evangelicalism was “dismal”.23 It was 1977, the Year of the Evangelical, and Tinder pointed out that “most people get the impression that evangelicalism is doing better nowadays”. Consequently, the prologue needed to acknowledge “that there is blessing present”. Morris Inch, chairman of the Department of Biblical, Religious, and Archaeological Studies at Wheaton College, agreed. Inch expressed that he personally felt an “overwhelming sense of gratitude for [the] evangelical movement” and wanted the prologue to reflect this sentiment. It needed less bite and more affirmative language. The motion to accept the prologue was defeated, and it was sent back to a committee appointed by the chair to be rewritten (41).

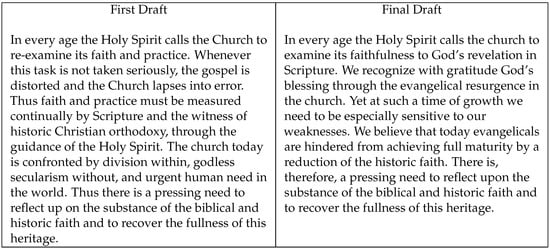

Webber and the executive committee had won the question of the conference’s subtitle, but they made significant concessions in the revised Prologue (Figure 1). The original draft began by stating that “in every age, the Holy Spirit calls the church re-examine its faith and practice”. The revised draft stated that the Holy Spirit calls the church to “examine its faithfulness to God’s revelation in Scripture”—a nod to the importance evangelicals placed on the authority of the Bible. The next two sentences, which suggest “whenever this task is not taken seriously, the gospel is distorted and the Church lapses into error” and that “faith and practice must be measured continually by Scripture and the witness of Christian orthodoxy” were cut. The notes provide no rationale for this decision; however, the removal of “the witness of Christian orthodoxy” as a yardstick for measuring faith and practice foreshadows how uncomfortable many conferees would be about any inference that church tradition and scripture were on the same authoritative level.

Figure 1.

First and final drafts of the Prologue.24

In keeping with the suggestion to adopt a more positive tone about the state of evangelicalism, the revised draft excised the statement that “the church today is confronted by division within, godless secularism without, and urgent human need in the world”. It also included the addition of three new sentences:

We recognize with gratitude God’s blessing through the evangelical resurgence in the church. Yet at such a time of growth we need to be especially sensitive to our weaknesses. We believe that today evangelicals are hindered from achieving full maturity by a reduction of the historic faith.25

Only one sentence remained unchanged between the original and revised drafts: an acknowledgement of the “pressing need to reflect upon the substance of the biblical and historic faith and to recover the fullness of this heritage”.

Disagreements about the Call’s tone would continue throughout the conference. Halfway through the drafting, for example, Webber gave what the plenary session notes describe as a “pep talk” to the group, enjoining them to be more focused and succinct in their statements of the problem: “Too flat. Need succinct statement of problem. Why angry? … Get fists up. Don’t be theological sissies”. Conversely, in his reflections after the conference, Inch noted that “the actual mood of the group was negative against evangelicalism” and that he “especially fought for a positive prologue”.26

4.3. A Call to Historic Roots and Continuity

By all accounts, the question that most divided participants throughout the conference was how to situate the Reformation. As noted earlier, Webber saw the main divide at the conference as between “those who desired a more catholic expression and those who wanted to retain a language more common to the Reformers” (Webber 1978, pp. 31–32). Thomas Howard similarly noted an ideological divide between the conference planning committee and many of the attendees:

The “vibes” in the air were fascinating, since it had, in fact, been a smallish group who did, in fact, have “catholic” concerns who had done the spade-work for the conference. But that group was far, far out-numbered by men, most of whom were professional theologians of a starkly Reformational cast of mind.(Read et al. 1979, p. 12)

One camp sought to subordinate Protestant emphases and recover the theological vision of the early, undivided Church. Another camp argued that any future reformation of the church must incorporate the valid and enduring contributions of sixteenth-century Protestantism.

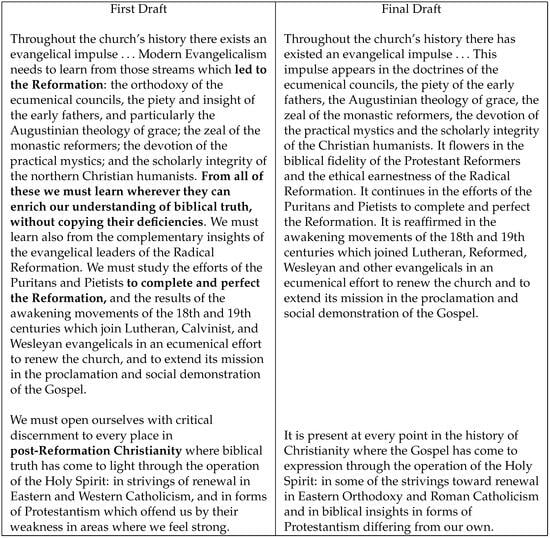

The first draft of the Call to Historic Roots and Continuity written during the conference favored the Reformation-centric perspective, as indicated by the phrases in bold (Figure 2). The ecumenical councils, the early Church Fathers, and the monastics, mystics, and Christian humanists all “led up to the Reformation”—language that suggested that sixteenth-century Protestantism represented an apex in theological thought. The sixteenth century remained the historical touchstone for the rest of the draft: Puritans and Pietists sought to “complete and perfect the Reformation”, and the contemporary church operated in the context of “post-Reformation Christianity”.

Figure 2.

Early and final drafts of “A Call to Historic Roots and Continuity”.27

The final draft is less directive. Historical streams no longer lead to or from the Reformation. Instead, the verbs suggest a nonhierarchical, logical progression: “appears”, “flowers”, “continues”, and “is reaffirmed”. The handwritten session notes indicate that the conferees debated vigorously about how to portray this trajectory. The sentence explaining that the evangelical impulse “flowers in the biblical fidelity of the Protestant Reformers and the ethical earnestness of the Radical Reformation” was particularly controversial. Some argued that the verb “flowers” was problematic because it “makes the Protestant Reformation ultimate”. Couldn’t another verb—“shines”, “matures”, “blossoms”—make the point more effectively? Other members had concerns about traditions the metaphor excluded. As Roman Catholic participant Father Benedict Viviano recounts,

Someone suggested that there might have been an effort at biblical fidelity within the Church of Rome and not only among the Protestant Reformers. At that, another defended the original wording on the grounds that “Trent was no flower, baby.” I piped up, “Not even a tiny violet?” “A merest forget-me-not?” impishly added another. The original wording was retained, despite our gallant efforts.(Viviano 1978, p. 228)

The Reformation-centric members of the conference had to compromise on the Call to Historic Roots and Continuity. However, they would prevail in another section of the document. In the working outline of the Call to Creedal Integrity, conferees were asked to “affirm the normative value of the ecumenical creeds and the “contextual value of confessional statements”. Webber wanted to draw a distinction between the ecumenical creeds (which were “universal in character”) and the Reformation confessions (which were “valuable testimonies to the truth but limited by their local and parochial character”) (See Read et al. 1979, p. 10). The conference voted to put them both on an equal level.28

4.4. A Call to Biblical Fidelity

In the summer of 1976, just a few months before the organizers of the Chicago Call began planning their conference, Harold Lindsell published a book with a provocative title: The Battle for the Bible. Lindsell, who had served on the faculties of Chicago’s Northern Baptist Seminary, Wheaton, and Pasadena’s Fuller Seminary, argued emphatically that the Bible is inerrant, meaning it contains no errors in its original manuscripts. This claim extended beyond spiritual matters to include the Bible’s historical, scientific, and geographic assertions. Prior to Lindsell, evangelical leaders just as often described scripture as infallible, an older term indicating that scripture is reliable and trustworthy in matters of faith and practice. Lindsell, however, argued that an affirmation of biblical inerrancy was the litmus test distinguishing true evangelicals from those who wrongly claimed the title. Specifically, Lindsell launched scathing attacks on the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, the Southern Baptist Convention, and Fuller Theological Seminary as examples of formerly “evangelical” groups that had abandoned inerrancy and were falling into spiritual decline.

The organizers of the Chicago Call were united in their conviction that debates over inerrancy would not take over the conference discussion. The notes from the second pre-conference planning meeting including the following summary discussion about scripture:

Need to issue a call (idea by Tom Howard). He sees this as a witness to the evangelical community—to get people into the early church fathers. Authority of scripture—traditional. Position of Lindsell? Will carry only Fundys.29

The conference notes suggest that there was also robust conversation among the conference attendees over how to describe the authority of scripture. One person wondered if it was necessary use “infallible” at all since the word “invited misinterpretations and misunderstandings”. Others objected, “keep it! [sic]” and defended “infallible” as “germane” and “important to include” so “we’re not compromising on a high view of scripture”. A motion to strike the word “infallible” was made and defeated: a total of 12 were in favor of elimination and 22 opposed.

Some of the conservative-leaning Callers suggested ways of nuancing the notion of infallibility; in particular, they advocated for adopting language of the Lausanne Confession, which stated that the Bible is “without error in all that it affirms, and the only infallible rule of faith and practice”. Donald Tinder objected that the phrase “without error in all that it affirms” was “code language”—a wink to Lindsell’s notion of inerrancy without actually using the contested word. In the end, the group contented itself with affirming that the scriptures are “the infallible Word of God” and “the basis of authority in the church”. The notes do not reveal how the group came to this decision, but again, the reflections of Father Benedict Viviano shed light on how the dispute was resolved: “This word was chosen because it was traditional Reformation confessional statements and therein the word ‘infallible is followed by ‘in matters of salvation, doctrine, and life’. The word was so intended by authors of this portion of the Call, and it is in this sense that I signed the Call” (Viviano 1978, p. 231).

In addition to describing the inspiration of scripture, the conference notes and early drafts of the “Biblical Fidelity” section reveal a second, even more divisive issue amongst the Callers: articulating the precise relationship of the Bible to the Church. In a letter, Peter Gillquist spelled out the ethos behind the kind of statement on scripture that he and his colleagues on the executive committee were hoping for:

With the rise of individualism in our culture, Christian people have opted toward “private interpretation”, forgetting all about allowing the church to speak by consensus as to what Scripture really means. It has been each man individually before God with his open Bible. That hermeneutic will not carry the day, and needs to be dramatically challenged. … In the ancient church, men of God met in council to reach an agreement upon what it is that the Scriptures teach. Assuming that the figure of 50 million evangelicals in this country is correct, it would appear as though 50 million private councils are being held regularly to decide what the Scripture teaches on eschatology, ecclesiology, theology, submission and authority, eternal security, and even the doctrine of inspiration itself! We have left our forefathers and forgotten them.30

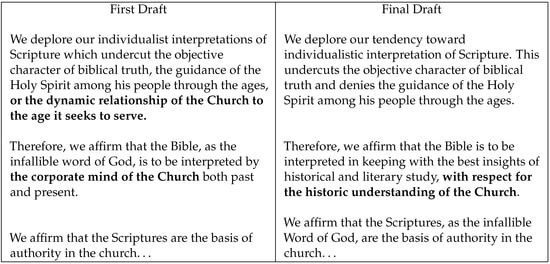

The original draft of “Call to Biblical Fidelity” leaned in the executive committee’s favor (Figure 3). For example, the proposed phrasing at that start of the second paragraph affirmed that “the Bible…is to be interpreted by the corporate mind of the Church both past and present”. However, this sentence went through several significant rewrites, and ultimately re-emerged as a very different idea.

Figure 3.

Early and final drafts of “A Call to Biblical Fidelity”.31

Morris Inch proposed dropping the reference to the Bible being “interpreted by the corporate mind of the Church” and instead affirming that the Bible is to be interpreted “in keeping with the best insights of historical and literary study with respect to the Church” (emphasis mine). Ray Nethery, a former Campus Crusade for Christ worker, lobbied to tweak Inch’s proposal: the Bible is to be interpreted not “with respect to the Church” but rather “in continuity with the Church”. The discussion notes indicate that Inch objected to Nethery’s wording as “too strong”.

At this point, David Wells, professor at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, jumped in to ask for a clarification: does interpreting the Bible “in continuity with the Church” mean that Christians had to endorse every interpretation of the ancient and medieval Church? Wells pointed to Luke 1:28, where the angel says to Mary, “Hail, O favored one, the Lord is with you”. Wells objected that in the late Middle Ages, this passage was widely understood to support the sinlessness of Mary—a doctrine which he vehemently opposed. In Wells’ view, saying that Christians read scripture “in continuity with the church” made the Bible subject to human history and conceded too much to the Roman Catholic perspective. Wells’ comments appear to have swayed the group. A vote was taken, and Nethery’s proposed language (“in continuity”) was defeated. In a second vote, Inch’s amendment (“with respect to the Church” instead of “by the corporate mind of the Church both past and present”) was unanimously approved.

It is worth noting how much the executive committee lost in the final compromise. In the materials sent to participants to study before the conference began, Webber suggested points of emphasis for each of the eight subsections. Under “Biblical Fidelity”, he suggested that attendees issue a call that would accomplish the following:

- Affirm a high view of scripture;

- Recognize the biblical witness illumined by the Spirit in the Church as the basis of authority, and the crucial role of church traditions in the proclamation of this witness;

- Replace subjective hermeneutics with one that respects the objectivity of the unique revelation given in biblical history and conveyed through church traditions.

In the end, the conference affirmed only the first point.

This was surely a disappointment. In an ecumenical forum about the Call published in the New Oxford Review in 1977, Anglo-Catholic respondent Rev. Canon Francis Read responded warmly to the Call but pushed back against the ambiguity of the sentence stating that the Bible is to be interpreted “with respect for the historic understanding of the Church”. “Who is to do this interpreting”, he queried, “and does ‘the church’ mean the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church of Christian history”? Canon Read argued that “in the absence of a comprehensive doctrine of the Church”, the sentence was “meaningless” (Read et al. 1979, p. 8). Robert Webber and Thomas Howard had no defense. “Canon Read rightly criticizes our statement as failing to have a comprehensive doctrine of the Church behind it”, Webber conceded, acknowledging that “the statement of the Call as it stands does not recognize the co-inherent relationship between the Scriptures, the Church, and the ministry” (Read et al. 1979, p. 10). Howard noted that he agreed “with virtually every syllable of Canon Read’s statement” and affirmed that Read was “right on the target when he observes that no solution is proposed for the problem of church authority in an independent-minded evangelicalism, nor is there any suggestion as to who is to do the interpreting of the Bible in the ‘Call to Biblical Fidelity’” (Read et al. 1979, pp. 12–13). The executive committee recognized its defeat.

4.5. A Call to Sacramental Integrity

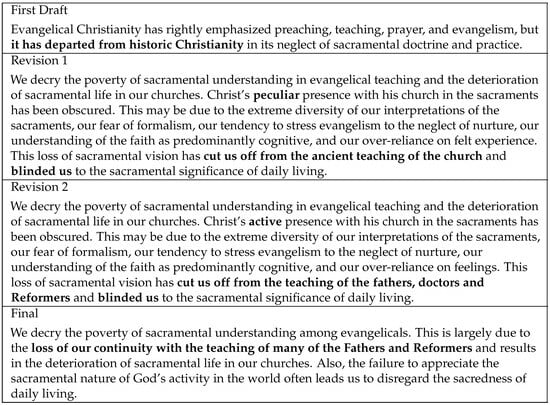

The Call to Sacramental Integrity was the most difficult section of the document to negotiate. It went through four stages: a first draft, two revised drafts (which were rejected by the conference), and the rewritten final draft, which was ultimately approved (Figure 4). The two most contentious issues were the nature of Christ’s presence in the sacraments and the notion of “sacramentality” outside the church.

Figure 4.

Early, revised, and final drafts of “A Call to Sacramental Integrity”.32

The first problem was naming how Christ was present in the sacraments. Richard Lovelace agreed that the evangelical church had “moved away from Reformation belief” insofar as “Zwingli becomes the norm”. He suggested that Calvin might provide a good middle ground. While Lovelace was not personally disturbed by the phrase “special presence”, he worried that it would be open to misinterpretation when read by a wider evangelical audience. Webber proposed replacing “special” with “active”, and Lovelace concurred, noting that “‘active’ says enough but not too much”. Donald Bloesch offered an alternative suggestion: the phrase “real spiritual presence”, which was used by the Reformers. Theodore Laesch, a Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod pastor, reflected that he would have no problems with either “special” or “active”, but he struck down Bloesch’s proposal of “real spiritual presence” as a bridge too far. A vote was taken, and the language of “Christ’s active presence” was adopted.

However, the second half of the statement, “with his church” was also subject to debate. Victor Oliver, editor-in-chief at Tyndale House Publishing, wanted to delete the phrase, arguing that it was “not well liked”. Donald Tinder suggested revising the sentence so that it read “Christ’s presence in sacramental observance has been obscured”, and a motion was made to adopt this language. Roman Catholic participant Benedict Viviano demurred, protesting that “observance” was too limiting, because Christ was present as a “prolonged reality” and not only “in the event”. A vote was taken, and Tinder’s proposal of “sacramental observance” lost, with 15 in favor and 19 against.

At this point, Roger Nicole of Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary argued that all language about Christ’s presence was a “red herring” and that the group should “leave it out”. Donald Bloesch concurred: like the infallibility issue, the question of eucharistic presence was bound to cause division. Another participant protested (“lots of evangelicals hold some sort of [notion of] presence”), but in the end, the group voted to strike the problematic sentence from the document entirely.

A second sentence also shows signs of heavy editing: “This loss of sacramental vision has cut us off from the ancient teaching/Fathers, doctors, and Reformers of the church and blinded us to the sacramental significance of daily living”. Richard Lovelace, also from Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary, raised two objections. First, he thought the phrase “cut us off from” was too passive: many of the Reformers deliberately moved away from the teachings of those who came before.33 Webber wondered if the problem could be solved by dropping “doctors”. Lovelace agreed that this was an improvement but argued that it was still problematic: he, for example, would not want to include Origen among the list of “Fathers”.34

Before the issue of the doctors and Fathers could be resolved, Donald Bloesch moved to strike the phrase “blinded us to the sacramental significance of daily living” from the statement. David Wells’ response to the Chicago Call in The Orthodox Evangelicals offers clarity about his specific objections to the phrase. Wells observed that Christ himself instituted only two sacraments, Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, but others at the conference wanted to infuse the entire created order with sacramental significance. “Forgive me for asking, then, but on what grounds to the Callers prescribe as sacramental what the church’s head, our Lord Jesus Christ, declined to do”? he asked (Wells 1978, p. 220). In the end, Bloesch and Wells lost the fight to drop “the sacramental significance of daily living” by a narrow margin. Sixteen people voted against the phrase; nineteen voted to retain it.

The notes indicate that by now, the group had gone well beyond the allotted time for discussion. Nevertheless, heated debate continued. Gordon Saunders of Trinity College voted to excise the entire controversial sentence: the Call to Sacramental Integrity would have no reference to being cut off from the early Church Fathers or being blinded to the sacramental significance of daily living. Another conferee seconded this move. Others spoke out against Saunder’s suggestion. A motion was made to appoint a committee to “fix it up and come back”. The committee that originally drafted the statement was not in favor of further revisions; everyone else at the conference voted in favor of the motion. Thomas Howard appointed a committee comprised of Roger Nicole, Robert Webber, Benedict Viviano, and Jeffrey Steenson to rework the statement and present it again later for a vote.

What was lost from the first to the final version? The first draft of the “Call to Sacramental Integrity” pulled no punches: the writers declared that evangelical Christianity had “departed from historic Christianity in its neglect of sacramental doctrine and practice”. This rhetoric was toned down slightly in the first and second revisions: rather than “departing from” historic Christianity (active language that hints at heresy) evangelicals were experiencing a “loss of” sacramental vision that had caused them to become “cut off” and “blinded” (passive language that suggests an accidental or unintentional turn of events). The verbs were softer still in the final draft: evangelicals “failed to appreciate” God’s sacramental action and were often “led to disregard” the sacredness of daily living.

Whereas the original draft called out specific deficiencies in evangelicalism (“neglect of sacramental doctrine and practice” in the first draft; “poverty… in evangelical teaching and the deterioration of sacramental life” in the two revisions), the final statement substituted weaker, less specific language. It simply decried “the poverty of sacramental understanding among evangelicals”. The final statement has no mention of Christ’s active presence with the Church in the sacraments and omits the forceful statement referencing “the extreme diversity of [evangelical] interpretations of the sacraments, our understanding of the faith as predominantly cognitive, and our over-reliance on feelings”.

5. Conclusion: Assessing the Debates

The drafters of the Chicago Call were divided by two conflicting interpretations of evangelicalism, as illustrated by two books published in 1978. The first, The Orthodox Evangelicals—a product of the Chicago Call conference and edited by Robert Webber—argued that the maturity of evangelicalism depended on aligning more closely with the broader Christian tradition. The second, The Evangelical Challenge by Morris Inch, sought to challenge “badly worn stereotypes” of evangelicalism and present the movement in a more positive light (Inch 1978, p. 10). Both books, written by Wheaton College professors, shared a common concern for strengthening evangelicalism’s ties to historic Christian orthodoxy. However, they differed significantly in spirit, character, and perspective. Webber’s tone was self-critical and open to correction; Inch’s was self-assured and prepared to witness (Oliver 1981, p. 168). The Chicago Call conference showed how difficult it was to reconcile these two competing perspectives.

In his introduction to The Orthodox Evangelicals, Webber stressed his appreciation for this evangelical establishment, even as he expressed his hope to move beyond it: “we take very little, if any issue with the doctrine of our current fathers” (Webber 1978, p. 19). However, conference participant James Daane argued that key theological concerns of the Chicago Call—things like respect for sacraments and a recognition of the Church as the context of biblical authority—could not simply “grow” out of the evangelicalism of the 1970s in the way Webber was hoping. “Some drastic pruning will have to be done first”, he warned (Daane 1979, p. 28). In time, Weber came to agree. Twenty-five years after the Call was issued, Webber suggested that the reason the Chicago Call was “largely ignored by the evangelical establishment” was because “there was no room in the evangelical subculture for this kind of witness to historic Christianity” (Webber 2002, p. 35). Ultimately, many of the conference organizers sought out new ecclesial paths. While never repudiating small “e” evangelicalism, Webber became an Anglican, Thomas Howard joined the Roman Catholic Church, and Peter Gillquist led his congregation into Eastern Orthodoxy.

“Establishment evangelicals” like Morris Inch, Donald Tinder, and David Wells recognized and shared many of Webber’s critiques of the movement. For them, however, the answer was not to leave low-church evangelicalism for the supposedly greener pastures of Anglican, Roman Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox churches. David Wells, who ultimately declined to sign the Chicago Call, would himself come to publish strong criticisms of contemporary evangelical movements.35 He nonetheless voiced his opposition strongly to the type of criticism found in the Chicago Call:

I cannot be persuaded that [evangelicals] would be substantially better off venerating Catholic saints than pretty starlets, or that sober-faced genuflectors and swingers of incense are much to be preferred to the vacant worshippers some of our churches are creating. This may be a time of small happenings, of pygmy spirituality, but a mass pilgrimage into the world of Anglo-Catholicism is not, with all due respect, what we need right now. Indeed, it is not what we need at any time.(Wells 1978, p. 214)

Three examples from letters and editorials published in response to the Chicago Call help illustrate how the “establishment” vision of evangelicalism differed from “catholic” evangelical understanding. In the first letter, a Baptist reader Winn Barr wrote to Christianity Today with a critique that echoed David Wells’ concerns. Barr affirmed that “on the whole, the Chicago Call gives us valuable suggestions” but wondered, “do I detect in it an implied rebuke to all free Christians and free churches”? He was skeptical that the Chicago Call would “dislodge those who really believe in direct access and personal responsibility to Jesus Christ”, and it certainly would not change the minds of those who understood baptism and the Lord’s Supper as ordinances rather than sacraments. As Barr put it, “such people [low-church evangelicals] …will accept common interest as the basis of unit cooperation within the fellowship of their kind and as the limit of cooperation with other kinds of Christians” (Barr 1977, p. 6). In other words, for many evangelicals, the grounds of Christian unity did not lie in a rediscovered past but rather in the shared concerns of the present.

A second critique came from John Walvoord, president of Dallas Theological Seminary, who argued that the “common interest” that united establishment evangelicals was an appeal to scripture, not history. Webber claimed that in the planning stages of the conference, the organizers’ modus operandi “was to make a list of all evangelical schools and institutions and draw representatives from them” (Webber 1978, p. 30). However, conservative-leaning evangelicals like Walvoord noted that their institutions were excluded:

Signers of the “Chicago Call”, while not to be identified as representatives of their respective institutions, nevertheless reveal some significant omissions. Institutions such as Moody Bible Institute, as well as the entire Bible institute movement, and such seminaries as the Conservative Baptist Theological Seminary, Dallas Theological Seminary, Grace Theological Seminary, Talbot Theological Seminary, and Western Conservative Baptist Seminary are all absent and without representation. It is evident that the “Chicago Call” is attempting to provide a standard of orthodoxy short of the rigidity of the inerrancy movement, and yet to the right of neoorthodoxy.(Walvoord 1979, p. 359)

Carl F.H. Henry lodged a similar complaint: “In their effort to move beyond fundamentalism and establishment Evangelicalism to a more inclusive view, the conveners of the Call invited only a slim minority of participants committed to inerrant inspiration” (Henry 1979, p. 4). Webber’s “catholic evangelicalism” was inclusive of high church traditions but less so of fundamentalists, dispensationalists, and those who were committed to the doctrine of inerrancy.

In a third example, Edward Crossmore, a reader of Christianity Today, wrote to the magazine with reservations about how the Chicago Call described the relationship between scripture and tradition. Recall that during the debates over the “Call to Biblical Fidelity”, catholic evangelicals lobbied to affirm that the Bible is interpreted “by the corporate mind of the Church both past and present” or “in continuity with the Church”. Establishment evangelicals, led by Morris Inch and David Wells, talked the group into a more watered-down affirmation that “the Bible is to be interpreted…with respect for the historic understanding of the Church”. For Crossmore, even that statement was a bridge too far:

[The Chicago Call] would have us interpret Scripture “with respect for the historic understanding of the church”. … Surely the intentions of the biblical authors are not in the least influenced by the writings of Athanasius the Great, Augustine, Calvin, or the edicts of any post-apostolic council. … Let us not be ignorant of the much bad fruit borne by the Roman Catholic doctrine that sacred tradition together with sacred Scripture make up the Word of God.(Crossmore 1977, p. 8)

The authority of scripture was paramount for many evangelicals, and they would not be able to hear any of the Call’s recommendations or correctives until that issue was addressed.

In the end, if Webber and the catholic evangelicals were disappointed in the outcome of the conference, it was because their side had conceded many important points:

- The Prologue lost much of its sharp rhetorical “bite”;

- Qualifying adjectives were added to temper an uncritical embrace of early church teachings (i.e., “some of the strivings toward renewal in Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism” and “continuity with the teaching of many of the Fathers and Reformers”);

- The Council of Trent was pruned from the evangelical lineage;

- Any sense that Christians read scripture “in continuity with” the historic Church was lost;

- There was no acknowledgement of Christ’s presence—whether “real”, “special”, or “active”—in the sacraments, nor any recognition of the sacramental significance of the created order.

Conversely, if Inch, Tinder, Wells, and other establishment evangelicals felt disappointed by the conference, it was because they perceived the overall tone of the gathering as excessively critical and felt that their concerns about the authority of scripture were not adequately addressed. For whatever other successes it may have achieved, the “Chicago Call: An Appeal to Evangelicals” failed to unify the fragile and unwieldy coalition to whom it was addressed.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was collected and analyzed in this research.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge with gratitude the help I received from Emily Banas and other staff members at the Special Collections on Evangelism and Missions at the Billy Graham Center in Wheaton, Illinois. Thanks also go to Alexander Callaway and to JCR for their research assistance. I am especially grateful to Mark Noll for his insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See especially: (Coffman 2012; Neff 2012; Shelton 2004; Johnson 2002; Congdon 2024). |

| 2 | Thomas Nelson provided financial backing for the conference and also published The Orthodox Evangelicals. |

| 3 | Bloomington, Indiana [Orthodox Church of America]. “In Memoriam: Archpriest Peter E. Gillquist”. In Memoriam: Archpriest Peter E. Gillquist-Orthodox Church in America. https://www.oca.org/in-memoriam/archpriest-peter-e.-gillquist (accessed on accessed on 7 September 2024). |

| 4 | Thomas was the son of Philip Howard, president/publisher/editor of The Sunday School Times. His sister, Elisabeth Elliot, became a missionary to Ecuador, where her husband died trying to evangelize the Waorani people. His brother David headed the World Evangelical Alliance for a decade. |

| 5 | In this passage, Webber refers specifically to a small cadre of young men and women who were…eminently qualified to provide leadership in calling such a conference” (emphasis mine). Webber then lists seven men and one woman, Isabelle Erickson, book editor at Tyndale House and the spouse of committee member Gerald Erickson. However, in Webber’s unpublished draft of this chapter, he refers only to “a small cadre of young men”. Isabelle’s name never appears in the minutes of the nine planning meetings, which always began with a roll call of those present. There is no asterisk next to her name (indicating an executive committee member) in the list of signatories published after the conference. One suspects she was added to give more gender balance to the official account. |

| 6 | The steering committee met in March 1977. Their efforts led to the “Consultation on Evangelical Concerns, which took place in Atlanta, Georgia during December 1977 and the “Continuing Consultation on Future Evangelical Concerns”, which was held in December 1978. |

| 7 | http://web.archive.org/web/20100928034543/http://65.175.91.69/Reformation_net/Pages/ICBI_Background.htm. Accessed on 7 October 2024. The fact that this conference was held so close to Wheaton lends credence to the idea. Donald Hoke was the common link between these two conferences. He, like Webber, was working at Wheaton College at the time, which may explain how Webber got his insider information. |

| 8 | Notes from the second planning meeting report, “Consider possible date change for conf. from Oct. 77 to May 77—thinking here is that perhaps our conf. would be better before the other two Fall 77 confs”. |

| 9 | The planning meeting dates were December 4, 10, 26, 27 (1976), and January 2, 6, 12, 15, 21 (1977). |

| 10 | Elisabeth Elliott was a critically acclaimed author and speaker. Cheryl Forbes was the assistant editor of Christianity Today. Madeleine L’Engle was a Newberry Award-winning author: in addition to other works, her famous young adult novels, A Wrinkle in Time (1962) and A Wind in the Door (1973) would have been well known at this time. No suggestions of “other women” appear in the notes. |

| 11 | Here, I am using my best deductive reasoning. Names on the list were marked with the letter “P”, “B”, or “Q”, but there is no explanation for these abbreviations. “P” names seem to be the most famous and influential invitees, and “B” names appear to be second priority. The “Q” list is the shortest and might be a reserve list of alternates. |

| 12 | Other top-priority names included Marvin Anderson (Fuller), F.F. Bruce (Manchester University), James Daane (Fuller), Elisabeth Elliot, Cheryl Forbes, Michael Green, Arthur Holmes, Madeleine L’Engle, Bruce Lockerbie, C.T. McIntyre, Eugene Osterhaven, Larry Richards, Gordon Saunders (Trinity), Robert Stamps (Oral Roberts University), and Loren Wilkenson (Seattle Pacific) |

| 13 | Jim Hedstrom (doctoral student, Vanderbilt), Jeffrey Steenson (doctoral student, Harvard), and Lance Wonders (doctoral student, Dubuque). |

| 14 | Second-priority names included John Baird (Dubuque), Victor Cruz (Dubuque), George Farrell (University of Iowa), Donald Frisk (North Park), Richard Jensen (Wartburg Seminary), Killian McDonald (RC, Collegeville Institute), F. Burton Nelson (North Park), Rudolph Schade (Elmhurst), and Benedict Viviano (RC, Aquinas Institute). |

| 15 | Gillquist’s names included Dick Ballew*, John Braun*, Bishop Goodwin Hudson, Ken Jenson, Archbishop Joseph McKinney, Ray Nethery*, Jack Sparks*, Kevin Springer*, Gordon Walker*, and Ted Williams. The names marked with an asterisk indicate former Campus Crusade workers who were now part of Gillquist’s New Covenant Apostolic Order. |

| 16 | The eight additional names were Jon Alexander, Al Glenn, John Guest, Russell Hitt, David Howard, Kathryn Lindskoog, and Roger Nicole. Lindskoog’s name had previously appeared on the waiting list. |

| 17 | In addition to the three students—Jim Hedstrom, Jeffrey Steenson, and Lance Wonders—the three other names were James Daane, Eugene Osterhaven, and Gordon Saunders. |

| 18 | For example, Donald Bloesch proposed the name of Richard Lovelace (Gordon–Conwell) to Robert Webber in a letter dated February 28, 1977. Lovelace would have received his invitation in early March. |

| 19 | For example, consider the thirteen attendees who were invited with the least amount of notice. Two were pastors of local Wheaton churches: Nathan Goff (College Church, Wheaton) and Theodore Laesch (St John Lutheran Church, Wheaton). Three of the attendees worked at Wheaton College: Morris Inch and Herbert Jacobsen were professors and Lois Ottaway worked for Wheaton College News Service. Donald Dayton (North Park) and David Wells (Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) worked in nearby Chicago, as did Luci Shaw (author). Kenneth Jensen (New Covenant Apostolic Order) was leading a church in Indianapolis, only a three-hour drive away from Chicago. Of the remaining five attendees, at least two traveled from some distance: Richard Lovelace (Gordon–Conwell) and Howard Loewen (Mennonite Brethren Bible College). It is unknown how far the final two attendees—Donald Tinder (Christianity Today) and Matthew Welde (Presbyterians United for Biblical Concerns)—lived from Wheaton at the time. |

| 20 | There is some confusion about the final number of participants. In an unpublished draft of The Orthodox Evangelicals, Webber states, “Of the forty-six scholars, pastors, theologians, and students who attended The Chicago Call, only three found they were unable to sign the statement which The Call issued”. (Emphasis mine.) In the published book, Webber revises that number to forty-five. Three individuals opted out of signing. David Wells differed from the group consensus. Jon Alexander (Aquinas Institute) was a Dominican, and worried that his signature would commit the whole fraternal order. Finally, Webber writes that a third individual “feared that signing the statement would draw unpleasant reprisals from the institution he served.” Webber was referring to Richard Jensen of Wartburg Seminary. Jenson originally signed the document (his signature appears in the version printed in the 17 June 1976, issue of Christianity Today), but he must have changed his mind before The Orthodox Evangelicals was published: his name is not included in the list of signatories in that volume. Adding to the confusion is the fact that the name “Eric Lemmon” (assistant professor of theology at Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary) appears in the printed list of participants that all the conference attendees received. However, Lemmon did not sign the Call, and there is no further mention of him in either the primary or secondary sources. |

| 21 | Inch, Wells, and Tinder were not among the 48 individuals who originally received invitations. Wells’ name appears on the “Q” (reserve) list. Donald Tinder was likely a substitute for the original Christianity Today invitee, Cheryl Forbes. |

| 22 | “Minutes of Planning Meetings, 1976–1977”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 1, Folder 1. |

| 23 | All quotes from conference attendees come from “Minutes 2 May 1977, meeting” and “Minutes, May 1977 meeting”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 1, Folders 8 and 9, unless otherwise stated. |

| 24 | “Drafts: Prologue”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 1, Folder 10. |

| 25 | “Drafts: Prologue”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 1, Folder 10. |

| 26 | “Miscellaneous Papers, February 1977”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 2, Folder 2. |

| 27 | Drafts: A Call to Historic Roots and Continuity”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 1, Folder 14. |

| 28 | The approved statement read: “We affirm the abiding value of the great ecumenical creeds and the Reformation confessions”. |

| 29 | “Minutes of Planning Meetings, 1976–1977”, Records of the Chicago Call, BGC Archives, CN 033, Box 1, Folder 1. |