Abstract

Han Yu 韓愈 was a prominent literatus in the Tang dynasty and an influential figure in the history of Chaozhou culture. From the Song dynasty, the Neo-Confucian teachings became popular, and Han Yu was revered as a significant pioneer; hence, his position was raised to a new height. In Chaozhou, local officials and the literati continuously emphasized Han Yu’s significance to Chaozhou culture and education and built many temples and academies devoted to him. As a deity, Han Yu was viewed as a representative of Confucianism and was typical of orthodoxy sacrifices. The present article clarifies the origination and transmission of the Han Yu belief in the Chaozhou region and explores the process of deification and the spread of Chinese popular religion. Although local officials and the literati spared no efforts in promoting the Han Yu belief, the belief never became popular among Chaozhou people. Local officials and the literati focused on different aspects of the Han Yu belief. They stressed the orthodoxy of the belief and were never concerned with miracles. What they were concerned with and endeavored for somewhat hampered the spread of the belief among the masses.

Keywords:

Han Yu; belief; temple; academy; orthodoxy; deification; Chaozhou; local culture; transmission; Chinese popular religion 1. Introduction

Han Yu 韓愈 (768–824), born in Heyang 河陽 (today Mengzhou 孟州, Henan 河南 province), was a prominent literatus in the Tang dynasty and an influential figure in the history of Chaozhou 潮州 culture. In his lifetime, Han Yu propounded Confucian orthodoxy to maintain and restore the ruling order of the Tang court. In the fourteenth year of Kaiyuan 開元 (819), Han Yu submitted a memorial entitled Jian ying fogu 諫迎佛骨, also known as Lun fogu biao 論佛骨表, to Emperor Xianzong 憲宗. In the memorial, he elaborated on the hazards of Buddhist worship, criticized Emperor Xianzong for welcoming and offering sacrifices to Buddhist relics, and advised Emperor Xianzong to destroy Buddhist relics (). His sincere advice, however, provoked Emperor Xianzong to punish him: Han Yu was immediately relegated to the governor of Chaozhou, a city exceedingly far from Chang’an 長安. In Chaozhou, Han Yu did not lose heart and fulfilled his responsibility. During his eight-month term, Han Yu endeavored to remove the threat of crocodiles, valued farming, released slaves, and promoted local education (). Although Han Yu attempted to contribute to local people, he was not able to bring much change to Chaozhou in a short period. For example, crocodiles still endangered Chaozhou people during the Song dynasty. It was, however, during the Song dynasty that local officials began to publicize Han Yu’s contributions to Chaozhao and build a temple for him. From the Song dynasty, Neo-Confucian teachings became popular, and Han Yu was revered as a significant pioneer; hence, his position was raised to a new height. In Chaozhou, local officials and the literati continuously emphasized Han Yu’s significance to Chaozhou culture and education. He was shaped into a mentor to enlighten Chaozhou people. Han Yu gradually became a key figure in the transformation of Chaozhou’s history and a symbol of Chaozhou civilization. Consequently, many areas were created and/or marked with Han Yu; for example, the largest river Exi 鱷溪 in Chaozhou was renamed Hanjiang 韓江. Another kind of site elevated Han Yu’s position to the highest level, i.e., temples. Han Yu became a deity and was presented with sacrifices in Chaozhou for more than a thousand years. As a deity, Han Yu was viewed as a representative of Confucianism and was typical of orthodoxy sacrifices (zhengsi 正祀) initiated and supported by local officials and the literati. They never worried about the image of Han Yu and never spared efforts in adapting the beliefs of Han Yu to national policies on sacrifices. From the Song dynasty onward, many local deities changed and had to adapt themselves to national policies by revising their background and performing miracles. They aimed to be recognized as orthodox sacrifices or at least avoid being labeled as illicit sacrifices (yinsi 淫祀).1 During this process, the literati and local officials played dominant roles in interpreting these local deities and negotiating with the court.

The process of deification and the spread of deities are important topics in the study of Chinese popular religion. From the Song dynasty onward, China underwent tremendous changes in its demographic, political, intellectual, and social landscape (see ; ; ; ). Chinese popular religion entered a new era, with great changes in its national religious policies, regional economy, and social culture (). Hymes argued that the concerns and self-conceptions of the local elite shifted significantly, i.e., a turn from national to local spheres of interest, and increasingly supported the rise of local deities (). Local deities were confronted with new challenges and opportunities, and a few developed into nationwide deities. Watson explored how the Empress of Heaven transformed from a village god to a national deity from the Song to the modern period, and how this deity was interpreted and accepted by various groups. Watson pointed out the significance of the state and argued that the state exercised control over the religious lives of ordinary people by subtle means (). Duara used the concept of “superscription of symbols” to explain the complexity of Emperor Guan myths and interpret the wide spread of the belief of Emperor Guan (). Hansen used secular sources to analyze popular religious change in the Southern Song dynasty. She argued that the Song dynasty witnessed great changes in popular religion; many new deities and regional cults sprang up, and miracles became the core of popular deities (). Kleeman continued the discussion of regional cults. He described the history of the deity Wenchang 文昌 and discussed how a local deity developed into a national deity of imperial civil examinations (). Zhu Haibin 朱海濱 focused on changes in national policies on sacrifices from the Song to Qing dynasties and explored the spread of important national and local deities in Zhejiang 浙江, such as Emperor Guan, Zhou Xiong 周雄, and Hu Ze 胡則. He argued that many groups adapted these deities to national policies and regional natural and human environments when they became widespread in a certain region (). The spread of Chinese popular religion has been the subject of many studies, especially nationwide deities like Emperor Guan. Ter Haar performed a comprehensive study of Emperor Guan and explored the wide spread of Emperor Guan. He highlighted the significance of oral culture and reflected on previous different models and concepts of traditional Chinese religious culture ().

The present article clarifies the origination and transmission of the Han Yu belief in the Chaozhou region2 and further discusses different groups in the spread of Chinese popular religion. A few scholars have conducted pioneering research on the Han Yu belief in Chaozhou. Zeng Chunan 曾楚楠 studied Han Yu’s activities in Chaozhou and compiled related historical resources ().3 Wu Rongqing 吳榕青 expounded the origination and development of academies offering sacrifices to Han Yu (; ; ). Other scholars described the history of the Han Yu belief and explored how and why the belief rose in Chaozhou. They emphasized that the Han Yu belief was profound and popular among Chaozhou people, but their discussion only concentrated on the ancestral Temple of Han Wengong in the center of Chaozhou (; ; ). Although local officials and the literati spared no efforts in promoting the Han Yu belief, they never became popular among Chaozhou people. The primary religious practice of Chaozhou people was described as “worshipping deities” (bai laoye 拜老爺). In the fieldwork, we can see that the number of temples ranges from one to over ten in villages/communities; there are more than ten thousand temples and hundreds of deities, but only very few Han Yu cults have been discovered. This is irrational and abnormal. Local officials and the literati were the most powerful and influential groups in traditional China, but their efforts to spread the Han Yu belief failed to make an impression on the masses. This article uses the example of the Han Yu belief to reassess the position of the literati in Chinese popular religion. It contains three sections. The first section delineates the history of the Han Yu temples supported by local officials in the center of Chaozhou and affiliated counties. It explores how local officials promoted the belief and why the belief was able to be transmitted. The second section focuses on another kind of organization involved in the belief, that is, the academy. Han Yu was viewed as the most significant figure in the history of Chaozhou culture and was worshipped in many academies. This section describes the history of academies and the transformation of Han Yu as a deity in literature. The third section explores the Han Yu belief among the masses by using oral resources, vernacular literature, and investigation data. It discovers that the masses depicted a different image of Han Yu and failed to respond to the official promotion of the belief.

2. The Han Yu Belief and Local Officials

Local officials initiated the Han Yu belief in Chaozhou and continuously supported the ancestral Han Wengong Temple (Han Wengong Ci 韓文公祠) from the Song dynasty to the Republic. In the second year of Xianping 咸平 (999), a Chaozhou controller-general (tongpan 通判), Chen Yaozuo 陳堯佐 (963–1044), first built a temple devoted to Han Yu behind the office of the regional inspector, which was the origination of the Han Yu belief in the center of Chaozhou. In that year, Chen Yaozuo wrote the Verse Summoning Han Wengong (Zhao Han Wengong wen 招韓文公文) and a preface to record his pioneering work. He argued that the Han Wengong temple was typical of orthodox sacrifices against ghost worship, which was frequently associated with local deities and was labeled as an illicit sacrifice; therefore, the founding of the temple was the local officials’ responsibility:

Nanyue [people] mostly worship ghosts, but the Han Yu temple was not established. How can officials who manage local people be described as [who administer the policy of] benevolence? 南粵大率尚鬼,而公之祠弗立,官斯民者,又曰仁乎?()

His successors accepted this viewpoint and shouldered their responsibilities to maintain the Han Wengong Temple. In a thousand years (999–1949), the temple was relocated twice and was renovated or rebuilt more than twenty-eight times (). In 1189, a Chaozhou prefect (zhizhou 知州), Ding Yunyuan 丁允元4, relocated the Han Wengong Temple to the East Mountain (Dongshan 東山, a. k. a. Hanshan 韓山), where Han Yu frequently visited in his eight-month term. Henceforth, the temple was never removed and continuously supported by local officials. The supreme governors of Chaozhou became strong supporters, donating their salaries and appealing to colleagues for renovation or reconstruction. Among the twenty-eight times rebuilding work is known to have taken place, nineteen of the works were advocated by prefects (zhizhou or zhifu 知府) or commanders (zongguan 總管), six by provincial officials, and three by magistrates of Haiyang. Advocated by provincial officials, the supreme governors of Chaozhou were still significant participants and implementers. The end of the nineteenth century witnessed a largescale reconstruction of the Han Wengong Temple by provincial and local officials. In 1887, the governor-general of Liangguang (Liangguang zongzu 兩廣總督) inspected Chaozhoufu and ordered the Chaozhou prefect Fang Gonghui 方功惠 (1829–1897) to renew the temple. Fang Gonghui took seven years to accomplish the reconstruction project and considerably extended the temple.5

The continuity of the temple became a kind of political achievement and a way for local officials to express their indignation and ambition. The first initiator, Chen Yaozuo, was a famous grand councilor (zaixiang 宰相) and experienced ups and downs in his more than fifty-year career (). In 998, Chen Yaozuo was relegated to Chaozhou because his plain speaking enraged Emperor Zhenzong 真宗. Similar to Han Yu, Chen Yaozuo attached importance to local education and people’s hardships, i.e., renovating the Confucian temple and eliminating crocodiles (). Chen Yaozuo was obviously inspired by Han Yu, and this subsequently evolved into a fixed pattern for many Chaozhou officials. In a well-known inscription entitled Chaozhou Han Wengong Miao bei 潮州韓文公廟碑, Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101) pointed out that the Chaozhou prefect Wang Di 王滌 took Han Yu as the only model on which to cultivate talents and govern people (凡所以養士治民者,一以公為師) (). From the Song dynasty onward, Neo-Confucian scholars regarded Han Yu as their pioneer and continuously promoted his position. Su Shi praised Han Yu that his articles rectified the deteriorating writing style of the past eight dynasties, and his Confucian way saved the world from degeneration (文起八代之衰,道濟天下之溺) (). Han Yu became a role model for Chaozhou officials and was respected as a mentor for generations (baishi shi 百世師). The creation and renovation of the Han Wengong Temple demonstrated local officials’ admiration for Han Yu and their aspiration to follow Han Yu. In particular, local officials suffered setbacks in their official careers and demonstrated their indignation and indomitable spirit by supporting the Han Wengong Temple. In an inscription entitled Han Wengong Citang ji 韓文公祠堂記, the Chaozhou prefect, Xu Xiling 許錫齡, expressed his admiration for Han Yu and his disappointment in failing to contribute to the Han Wengong Temple. Xu Xiling assumed the role of prefect for only several months and was dismissed from office due a mistake by the subordinate magistrate. Before leaving, he visited the temple many times and wrote an inscription to express his sentiment (). The aim of the temple, moreover, was to cultivate and create loyal and righteous people (). Local officials had a responsibility to educate local people and promote good social customs, which were significant political achievements. Their primary means was to promote orthodox sacrifices. The Han Wengong temple was typical of orthodoxy sacrifices. Chaozhou officials attached great importance to the Han Wengong Temple and rebuilt it once destroyed. In the year 1575, the authorities pacified a prolonged period of banditry and chaos, and instantly rebuilt the Han Wengong Temple. A vice commissioner, Jin Zhi 金淛, initiated the rebuilding project and argued that the temple was closely connected to moral customs.6 The Han Wengong temple gradually became a reflection of the social and political situation. The establishment and abolishment of the temple were associated with the rise and fall of the world’s morals and were related to the merits and demerits of the administration (一祠之興革,固世道盛衰之攸關,吏治得失之所係).7

The Han Wengong Temple was destroyed and rebuilt more than twenty-eight times and left many inscriptions (see Table 1). These inscriptions were created by local officials and the literati, and reflected their views on the Han Yu belief. The extant eighteen inscriptions are as follows:

Table 1.

Inscriptions of the Han Wengong Temple8.

The above twelve authors were officials and initiators, primarily Chaozhou prefects or provincial officials. The content of each inscription was similar and generally contained four sections. First, they described Han Yu’s experience, highlighting his upright and unyielding heroism and emphasizing his contribution to Confucian orthodoxy. Second, the authors expressed their admiration for Han Yu and illustrated the significance of offering sacrifices to Han Yu. Third, the authors detailed Han Yu’s activities in Chaozhou and highly praised his contributions. Last but not least, they recorded the history of the Han Wengong Temple and demonstrated that the authorities valued the temple and continuously provided support. Similar contents can be seen in temple inscriptions of other deities. These inscriptions, however, reflect an unusual phenomenon with regard to temple inscriptions. Hansen argues that temple inscriptions contained modified miracle tales circulating at the time and can be used to study the social context of popular religion in the twentieth and thirteenth centuries (). Referring to the creation, intension, and content of the temple inscriptions, Hansen pointed out the following:

On certain occasions, often following the performance of a particularly marvelous miracle or the receipt of a title from the government, the followers, both literate and not, of a given deity joined together to sponsor the carving of a commemorative text onto a stele. Put up to impress people with the power of a god, steles were not necessarily designed to be read. The sheer magnitude of the stone (sometimes over two meters high and one and a half meters wide) amply conveyed both a deity’s power and the extent of support for him. The texts carved on steles often include a biography of the deity before his or her apotheosis, a history of the deity’s miracles, a list of titles received from the central government, and a physical description of the temple().

Miracles triggered the creation of temple inscriptions and constituted a significant (or even indispensable) aspect of them. Temple inscriptions, furthermore, became evidence of miracles and presented a deity’s efficacy. In a study on Zhejiang, Zhu Haibin argued that the wide spread of local deities relied upon miracles that adjusted to regional natural and human environments (). The meaning of miracles was obvious, and therefore their absence in all extant inscriptions of the Han Wengong Temple was most likely not an unintended consequence. This indicates that the authorities deliberately neglected all miracles and were never concerned about the efficacy of Han Yu. As a deity, Han Yu relied on his personality and charisma and constant support from the authorities.

From the sixteenth century, the authorities began to build temples devoted to Han Yu in affiliated counties of Chaozhou. During this period, national sacrificial policies returned to Confucian fundamentalism and highlighted the orthodoxy of temples (). In the year 1572, a Chaoyang magistrate, Huang Yilong 黃一龍, supported the building of the Han Temple (Hanci 韓祠) in the East Mountain of Chaoyang. It was the first Han Yu temple outside of the Chaozhou center, and prefectural officials had promoted the Han Yu belief for more than five hundred years so that it had reached a high level: “river and mountain were surnamed Han” (江山易姓為韓). In 1570, Huang Yilong took office in Chaoyang and suggested building a temple devoted to Han Yu since he was exceedingly worshipped in the center of Chaozhou and because Han Yu also had a connection with Chaoyang.9 His suggestion, however, did not receive a positive response. Two years later, Huang Yilong visited the Temple of Twin Loyalty (Shuangzhong Miao 雙忠廟, a. k. a. Lingwei Miao 靈威廟)10. He looked at his colleagues and sighed:

The Twin Loyalty came to Chaoyang because [the spirit of] Han Yu had been here. Now there are temples devoted to the Twin Loyalty, yet how can it only lack a temple devoted to Han Yu [in Chaoyang]? The statue of Han Yu ever stood in a Buddhist temple, but it had been abandoned for a long time. Even if it still stands today, how is it enough to show respect? It is said that Han Yu never visited the East Mountain, and hence can we build a temple for Han Yu on the site of the former Temple of Dongyue this year? 夫二忠之來,以韓公之所在也。今二忠有廟,公可獨無?且像公者,故在沙門,然廢久矣。縱今猶存,曷足以示崇重?聞公嘗至東山,其以東嶽故地祠公,自斯年始,可乎?()

On this occasion, his proposal was supported by colleagues and the local literati, especially Lin Dachun 林大春 (1523–1588), who was born in Chaoyang and became a reputable scholar and senior official.11 Huang Yilong spared no efforts in building the Han Yu Temple and utilized the belief of Twin Loyalty, an official and influential belief in Chaoyang, to accomplish his ambition. From the fourteenth century, local officials and the gentry increasingly focused on the belief of Twin Loyalty and emphasized their roles in protecting Chaoyang against bandits and pirates (). The Twin Loyalty gradually became guardians of Chaoyang. Moreover, they highlighted and constructed the connection between Han Yu and Twin Loyalty to establish the orthodoxy of the Twin Loyalty in Chaozhou (). In 1565, the Temple of Twin Loyalty was rebuilt after being destroyed by bandits; Li Dachun wrote an inscription for this reconstruction and acted as a witness to the connection between Han Yu and Twin Loyalty.12 Huang Yilong strengthened the connection and received support to build the Han Temple. Lin Dachun approved Huang Yilong and provided a portrait of Han Yu from his collection in order to create a divine image (). Based on these temples, local officials and the gentry created an atmosphere in which loyal officials could worship in the East Mountain of Chaoyang.13 This case in Chaoyang shows that the spread of the Han Yu belief in nearby counties was not smooth, even though the belief was highly valued in the center of Chaozhou. After a long period of hard work, the authorities constructed temples in the center of several counties (see Table 2 below).

Table 2.

The Han Yu temples in the centers of the affiliated counties14.

In Fengshun county, Han Yu was worshipped in the Temple of Eminent Officials (Minghuan Ci 名宦祠) (). The magistrates led the promotion of the belief in counties and connected the Han Yu belief to local education. In the Qing dynasty, many temples were transformed into academies (shuyuan 書院) or constituted the principal part of academies. Han Yu became a significant deity among the literati.

3. The Han Yu Belief and the Literati

In his term, Han Yu contributed to the promotion of local culture and education; hence, he was exaggeratively depicted as the founder of Chaozhou education and was worshipped in academies from the end of the Song dynasty. In Chaozhou, Han Yu donated his salary to support the prefectural school and appointed Zhao De 趙德, a metropolitan graduate (jinshi 進士), as the county defender (xianwei 縣尉) of Haiyang, taking charge of the school.15 Su Shi argued that Han Yu exerted a profound impact on Chaozhou education:

Initially, Chaozhou people did not know learning. Han Yu engaged metropolitan graduate Zhao De as their mentor, and from then, on Chaozhou people were altogether devoted to articles and morals. 始潮人未知學,公命進士趙德為之師,自是潮之人士皆篤於文行。()

Before the arrival of Han Yu, other Chaozhou prefects, including Zhang Xuansu 張玄素 (?–664) and Chang Gun 常衮 (729–783), had established schools and promoted local education (). Su Shi also realized that Han Yu was not the first figure to start a new era of Chaozhou culture and education. He excessively praised Han Yu and aimed to highlight Han Yu’s role in popularizing Confucian education among the lower and middle classes (). Su Shi’s viewpoint was accepted by some local officials, and they established the earliest academy in Chaozhou. In the third year of Chunyou 淳祐 (1243), Zheng Liangchen 鄭良臣, a Chaozhou prefect, founded the Hanshan Academy (Hanshan Shuyuan 韓山書院) on the south of Chaozhou city, in which the Han Wengong Temple was located before 1189. The academy primarily contained a lecture hall, a shrine, and four dormitories. The shrine was devoted to Han Yu (in the middle) and Zhao De (). In 1269, Zhou Dunyi 周敦頤 (1017–1073) and Liao Deming 廖德明 joined the academy; these were the Chaozhou controller-general and a disciple of Zhu Xi 朱熹.16 The academy enrolled twenty students, called zhaisheng 齋生, who prepared for civil examinations; the position of dean (shanzhang 山長) was occupied by an instructor of the prefectural Confucian school (zhouxue jiaoshou 州學教授) (). From the thirteenth to the early twentieth centuries, the Hanshan Academy was rebuilt, relocated, and renamed many times because of wars and official policies. It, however, never broke off and consecutively acted as a center of Chaozhou culture and education. The academy supplemented Confucian schools and trained students for civil examinations. Offering sacrifices to Han Yu was essential to the academy and led to an increase in Chaozhou education from the Tang dynasty. At the beginning of the Qing dynasty, the academy met both challenges and opportunities because of the vacillation of educational policies. In 1688, the Hanshan Academy was transformed into the School of South Corner (Nanyu Shexue/Yixue 南隅社學/義學), which provided public elementary education. In 1691, Shi Qixian 史起賢, a Hui Chao military defense circuit (Hui Chao bingbeidao 惠潮兵備道), established a new academy, which offered sacrifices to Han Yu, alongside the Han Wengong Temple in Mt. Han, and was named the Changli Academy (Changli Shuyuan 昌黎書院) (). In 1732, Long Weilin 龍為霖, a Chaozhou prefect, reiterated Han Yu’s groundbreaking advancement of education and extensively enlarged the academy, adding libraries, rooms, and the Kuixing Tower (Kuixing Ge 奎星閣). Moreover, the academy was renamed Hanshan Shuyuan.17 In the same period, the School of South Corner was retransformed into an academy named Chengnan Shuyuan 城南書院, which offered sacrifices to Han Yu and Wenchang 文昌 (). In the Qing dynasty, the worship of Han Yu gradually became a characteristic of many academies.

In affiliated counties, more academies provided sacrifices to Han Yu and enshrined him with deities of literature. From the Song to the early Qing, local officials and the literati established many academies with various functions and purposes, and only a few sacrificed to Han Yu. From the eleventh year of Yongzheng (1733), the court supported the development of academies and promoted their institutionalization and regularization as a special supplement to Confucian schools (). After the Yongzhen court, new academies also increasingly came into being in Chaozhou, and more academies offered sacrifices to Han Yu since his position had reached a peak and many temples had been built in affiliated counties. Based on local gazetteers (fangzhi 方志) and inscriptions, it is clear that fourteen academies offered sacrifices to Han Yu from the Song to the Qing dynasties (see Table 3 below).

Table 3.

Academies that offered sacrifices to Han Yu in affiliated counties18.

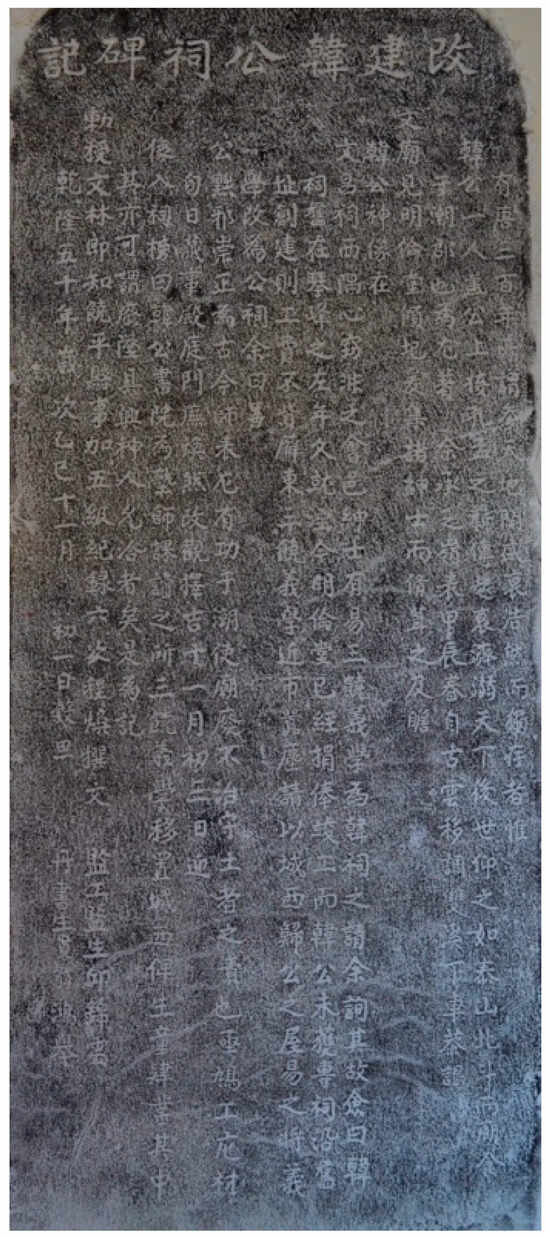

More than half were established in the Qing dynasty. The majority of academies were located in Haiyang, since the Han Yu belief originated in and was vigorously promoted in Chaozhou city. Depending on their connection with the belief, these academies can be divided into three groups. Firstly, some academies were in memory of Han Yu and initially offered sacrifices to him. Secondly, some academies were based on previous temples devoted to Han Yu. The temples were possibly extant or abandoned. Thirdly, some academies were transformed from other temples or initially sacrificed to other deities, frequently Wenchang and Kuixing. Some of these academies offered sacrifices to Han Yu at a time later than their creation time. This division was ideal, since the history of a few academies was complicated. The Hangong Academy was closely associated with the Han Wengong Temple established in the Ming dynasty. In the early Qing dynasty, the temple was abandoned, and the divine image of Han Yu was moved to a corner of Wenchang Ci. The gentry desired to reconstruct the Han Wengong Temple, but they failed because of underfunding. In 1785, the Raoping magistrate, Chen Huan 陳煥, and the gentry transformed the School of Sanrao (Sanrao Yixue 三饒義學) into the Hangong Shuyuan to sacrifice to the divine image and revive the Han Yu belief. Chen Huan wrote an inscription entitled Gaijian Hangong Ci beiji 改建韓公祠碑記19 (see Figure 1). The above table shows that many academies connected with the Wenchang temples. Academies frequently focused on the worship of Wenchang and Kuixing, since academies specially trained students for civil examinations in the Qing dynasty. Consequently, Han Yu was enshrined with deities of literature and became a deity of civil examinations in Chaozhou. In 1810, the literati of Zhanglin 樟林 asked the Chenghai magistrate, Qi Shouye 齊守業, if they could regain the Temple of Zhuzi (Zhuzi Ci 朱子祠) and transform it into the Temple of Wenchang. Four years later, the Temple of Wenchang was completed and devoted to Wenchang as the main deity and Han Wengong and Zhu Wengong 朱文公 as secondary deities. The newly appointed Chenghai magistrate, Li Shuji 李書吉, additionally set up a free school inside (). However, the temple and its property subsequently were occupied many times. Chen Chunsheng 陳春聲 argued that this kind of temple supported by the literati possibly lacked a wide and powerful belief base ().

Figure 1.

A rubbing of Gaijian Hangong Ci beiji by the Author.

Han Yu’s miracles related to civil examinations can be dated back to the Song dynasty. On the East Mountain, which is also known as Hanshan, an oak tree20 was planted next to a pavilion where Han Yu frequently visited; this later became the location of the Han Wengong Temple. In the Song dynasty, the tree was planted by Han Yu and was named Hanmu 韓木, since nobody knew its name. It became a tradition that Chaozhou people observed the tree’s blossom in order to divine the result of imperial civil examinations. In 1097, 1106, and 1124, the oak tree was in full bloom and Chaozhou students made outstanding achievements.21 After 1189, the tree became a part of the Han Wengong Temple and a famous landscape praised by the literati. It was said that the tree came to bloom in 1744, and the result of civil examinations reached a peak (). This was the last miracle, and the tree died decades later.

4. The Han Yu Belief and the Masses

Local officials and the literati delineated Han Yu as a brilliant and virtuous official and mentor, which exerted an impact on the masses and was reflected in local legends. Su Shi described the legend of Han Yu in the Song dynasty, stating that Han Yu taught Chaozhou people to build tile-roofed houses; Su Shi argued that the legend was not true and dropped it from his inscription (). In Chaozhou, gazetteers of the Song and Yuan dynasties recorded four events related to Han Yu’s administration in Chaozhou. First, it was recorded that the ancient commandery seat was Yahu 鴨湖, which was located on the east side of the Han River, northeast of Chaozhou city today, and that Han Yu took office there. It was verified that Yahu was the seat before the Tang dynasty, and but it was found that Han Yu never took office there and was introduced into the legend to convince listeners. Second, villagers in Shuinan 水南, in the east of Chaozhou, spoke in a different tongue called bulao 不老. It was said that Han Yu taught Chaozhou people in the mandarin language in his term, which led to the formation of the bulao tongue. From the Tang dynasty, a large number of Fujian people immigrated to Chaozhou and brought new dialects. In the twelfth century, local dialects rapidly changed in Chaozhou, and the Min dialect gradually became a primary language. Local people could not interpret this linguistic phenomenon and needed Han Yu to explain it to them. Third, Han Yu made sacrifices to crocodiles in Shiguitou 石龜頭 behind Mountain Gold (Jinshan 金山) and established a Buddhist pagoda in the middle of the Han River to suppress the threat of crocodiles. It was verified that the development of Shiguitou was from the Song dynasty, and that Han Yu advocated the exclusion of Buddhism. Lastly, it was recorded that a wooden tortoise in a Daoist Temple did not rot in feces and was not destroyed by fire. It was said that the tortoise was made by Han Yu and had divine power. These Song and Yuan records were virtually legends, and the editors of gazetteers vigorously disputed their authenticity. These early legends reflected that Han Yu became a cultural symbol for verifying local history and explaining unknowns and abnormal phenomena (). The legends of Han Yu were passed down from the Song dynasty to the present. In the 1980s, a few legends were collected in Chaozhou city, and these recorded that Han Yu acted as a diligent official who worked for Chaozhou people. Han Yu was concerned about people’s hardship and welfare once he arrived in Chaozhou; in his term, he built the north embankment to prevent floods, offered sacrifices to crocodiles to get rid of them, imparted techniques for the planting of sweet potatoes, created a kind of washcloth (shuibu 水布) to help workers who transported timber in the Han River, socialized with Monk Dadian 大顛 (732–824),22 and initiated the construction of Xiangzi 湘子 Bridge (; ; ).

In vernacular literature, the image of Han Yu was slightly different and not so lofty. There were two early Chaozhou texts on Han Yu: Building the Pontoon Bridge () and Newly Complete Songbook on Giving Winter Clothing (). Zao Fuqiao, also known as Xinbian Zao Xiangzi Qiao 新編造湘子橋, was a script and was played by a theatrical troupe named Lao yutangchun ban 老玉堂春班. The script was published by Li Wanli 李萬利 in Chaozhou city before 1949. The version we collected was not complete and only included four parts (ji 集). The primary plot was that Han Yu built the Xiangzi Bridge, a pontoon, to help Chaozhou people avoid crocodiles. In his term, Han Yu saw crocodiles eating people when they crossed the Crocodile River (exi 鱷溪, also known as Hanjiang) by boat. Han Yu immediately sought help from Monk Dadian. Dadian readily helped him since Han Yu deeply respected him after assuming office. Dadian said that crocodiles were descendants of the Dragon King of the Eastern Sea, and it was difficult to eliminate them. Han Yu was determined to remove the scourge of crocodiles. Dadian practiced divination by fingers and told Han Yu that the scourge could be removed in a month. A merchant’s only son was severely harmed by crocodiles, and he was caught by the Dragon King. His wife sought help from Monk Dadian, who suggested that she should implore Han Yu to post an official notice inviting a courageous man to help. Liu Yishi 劉逸士 was good at martial arts and accepted the invitation. Liu was instructed by Dadian and was conferred magic weapons. Dadian asked Liu Yishi to invite his senior, Monk Guangji 廣濟23, to subdue the monsters. The monsters saw the notice and planned to seize Han Yu. Dadian advised Han Yu to let his servant, Li Wan 李萬24, pose as him. Li Wan was seized. Dadian and Guangji jointly repelled the monsters and rescued Li Wan and the merchant. In addition, Han Yu was going to build a pontoon to prevent crocodiles from eating people. Before the project, they needed to get rid of crocodiles. The subsequent plot is unknown.25 In this script, Han Yu was an ordinary person and excessively relied on Monk Dadian. The legend of Han Yu and the Xiangzi Bridge can be dated back to the Ming dynasty: “the aged said, sir Han Changli implored deities of the river; the river dried up for several days, and therefore the construction was able to start.” (故老相傳,昌黎韓公乞神於江,江為涸數日,因得而經始焉)26. The legend told in the 1980s included more details. Han Yu planned to build a bridge across the Crocodile River. Since its current was fast, Han Yu sought help from Han Xiangzi 韓湘子 (one of the Eight Immortals) and Monk Guangji. Han Xiangzi, with the other Eight Immortals and Monk Guangji, took charge of building a half of the bridge (). Currently, the bridge is known by the names Xiangzi qiao 湘子橋 and Guangji qiao 廣濟橋. In history, the bridge was first built around 1171 and named Jichuan 濟川; in 1435, the bridge was rebuilt and renamed Guangji 廣濟 (). In the front of the Xiangzi Bridge, the Temple of Han Xiangzi (Han Xiangzi Miao 韓湘子廟) was built in the Qing dynasty (). Moreover, Han Xiangzi was secondarily worshipped in the Temple of Han Wengong nearby (). From the nineth century, an uncle–nephew relationship between Han Yu and Han Xiangzi began to develop and led to the creation of many literary works (; ; ).

The lore of Han Yu and Han Xiangzi became the subject matter of popular literature and evolved into a set theme: deliverance (dutuo 度脫). The popular plot was that Han Xiangzi became an immortal through cultivating himself and returned to deliver his uncle Han Yu, aunt, and wife. An excellent example was the Newly Complete Songbook on Giving Winter Clothing, which was published by Wansheng Ji 王生記 in Chaozhou city before 1949. This songbook was a prosimetric text that was transmitted primarily among Chaohzou women. Its storyline began that Han Xiangzi, the reincarnation of a white crane with cultivation achievements, was reborn as the son of Han Yu’s elder brother. When Han Xiangzi was ten, his parents died, and Han Yu began to raise him like a son (since Han Yu had no children at that time). Han Yu had great expectations of Han Xiangzi: he could pass the imperial civil exam and extend the family line. Han Xiangzi, however, wholeheartedly sought the Way and cultivated himself under the instruction of his master immortal Zhongli Quan 鍾離權. Han Yu scolded Han Xiangzi and forced him to give up cultivation. Han Xiangzi ran away from home and jumped into a river. He was guided by his master and became an immortal. Han Xiangzi came back to deliver his relatives and spent most of his energy delivering Han Yu. Han Xiangzi arranged the event of Buddhist relics and instructed Emperor Xianzong to relegate Han Yu to Chaozhou. After Han Yu accomplished his tenure in Chaozhou, Han Xiangzi delivered Han Yu so that he could cultivate himself. Through cultivation, Han Yu received the jade decree (yuzhi 玉旨) to revive his heavenly office. The decree revealed that Han Yu previously was the Great General of Juanlian (Juanlian da jiangjun 捲簾大將軍) and was penalized for breaking the glazed lamp by being reincarnated to teach Chaozhou people. Overall, this storyline was adapted from the Ming novel the Complete Story of Han Xiangzi (Han Xiangzi Quanzhuan 韓湘子全傳). This novel was a great summa of Han Xiangzi lore, both from literary literatures and popular traditions; its earliest version can be dated to 1623 and was hitherto the most complex and developed version of Han Xiangzi lore, exerting a profound impact on the Han Xiangzi literature of the Qing dynasty (). The Chaozhou songbook possibly originated in the late seventeenth century, and the publisher Wangsheng Ji commenced the printing of songbooks in the second half of the nineteenth century (). By comparing the two literary works, the author of Songbook on Giving Winter Clothing abridged many plots related to Han Xiangzi’s cultivation and focused on how Han Xiangzi delivered Han Yu. The author supplemented the activities of Han Yu in Chaozhou, adding the new figures Monk Dadian and Zhao De, and deleted bantering plots to maintain a good image of Han Yu. By contrast, the image of Han Yu was secularized in most popular literature of the Qing dynasty beyond Chaozhou (; ; ). In these works, Han Yu frequently chose to become the tutelary god (tudi shen 土地神) since he enjoyed sacrifices of meat and wine. Among a few official bureaus in Beijing, Han Yu was worshiped as the tutelary god from the seventeenth century ().

This popular literature had an influence on Chaozhou morality books (shanshu 善書) created in the first half of the twentieth century. The modern period (1840–1949) witnessed the rise of the spirit-writing (fuluan/fuji 扶鸞/扶乩) movement as a response to crises. From the nineteenth century, spirit-writing cults sprang up throughout China. These cults were driven by a millenarian sense of mission, regarded moral exhortation as their very purpose of being, and were a product of the nineteenth-century movement of religious synthesis (). They devoted themselves to transmitting eschatological ideas as a way of saving the world from kalpa (jie 劫). Consequently, thousands of morality books, or specifically spirit-written books (luanshu 鸞書), were revealed and composed by deities by means of spirit-writing. In Chaozhou, the spirit-writing movement began to rise from the late nineteenth century and developed in the context of disasters, political chaos, and the transmission of foreign culture and religions. The movement reached its prime in the first half of the twentieth century and is represented by many spirit-written books recording their thoughts and activities (; ). In the more than thirty extant spirit-written books we collected, Han Yu descended as a deity and gave exhortations. He, however, appeared infrequently (only twice), which contradicted his significant reputation in Chaozhou. In his two appearances, Han Yu revealed his own experience to inspire and exhort Chaozhou people to cultivate themselves and achieve moral reform. First, Han Yu was relegated to Chaozhou because he did not believe in Buddha. He educated Chaozhou people and removed crocodiles with the help of Han Xiangzi. Han Yu realized the preciousness of Buddhism and Daoism and visited Monk Dadian three times. Han Yu repented the fact that he had refuted Buddhism and sought hollow wealth and rank (). In another spirit-written book, Han Yu revealed that Han Xiangzi delivered him many times, but he failed to wake and persisted in seeking senior rank and great wealth. After suffering setbacks in officialdom and on the path of banishment, Han Xiangzi successfully delivered Han Yu at Bull Pass (Languan 藍關). Han Xiangzi invited Han Yu to live in a temple and incarnated as Han Yu to fulfil his responsibilities in Chaozhou. Three years later, Han Xiangzi took Han Yu to cultivate himself and became a deity (). Although Han Yu descended as a deity to exhort people, his lifetime during the Tang dynasty was almost described as a negative example to stimulate people to cultivate themselves instantly.

As a deity, Han Yu was not ranked highly among the people, and belief in him was rare.27 Local officials and the literati spared no efforts in raising the position of Han Yu and worshipped him in many temples and academies. These promoting actions failed to resonate with the people.28 Without the support of local officials and the literati, almost all of these temples and academies came to an end. After 1949, the authorities ceased funding and all academies were closed down or transformed into modern schools. Only two temples were exceptional. The ancestral Temple of Han Wengong in Chaozhou was rebuilt in 1984 and redeveloped as a tourist attraction. Another Han Wengong Ci in Huilai was assigned to farmers after 1949 and was reconstructed as Hanwen Miao 韓文廟 by villagers and believers in 2010. In this reconstruction, it was merged with the Temple of Wenchang nearby and was supported by the spirit medium of Han Yu. In our fieldwork,29 only four temples were discovered:

- -

- the Han Wengong Ci in Longmenguan 龍門關, Linxi 磷溪 town, Xiangqiao 湘橋 district, Chaozhou,

- -

- the Han Wengong 韓文公 in Hubian 湖邊 village, Haimen town, Chaoyang district, Shantou,

- -

- the Han Wengong Zhi Ci 韓文公之祠 in Hemei 河美 village, Dongli 東里 town, Chenghai district, Shantou,

- -

- a niche inside the Jinzhou Gumiao 金洲古廟, in Jinzhou village, Waisha 外砂 town, Chenghai district, Shantou,

- -

- a shrine inside the Lingshan Si 靈山寺, in Tongyu 銅盂 town, Chaoyang district, Shantou.

The first temple was destroyed in 1956, but worship here has continued to the present. Legend has it that Han Yu dug ditches to improve irrigation and farming in Longmenguan.30 As a reward, villagers built the Han Wengong Ci. Historically, this temple was possibly established in the late Ming dynasty and acted as a management agency for irrigation works among eight villages31. Each village took turns to manage the temple for a year and preside over the ceremony to Han Yu on the nineth day of the nineth lunar month. After the ceremony, the management was transferred to the next village (). The second was small and built before 1949, beside the Temple of the Large-Lake God (Dahushen Miao 大湖神廟). In his term, Han Yu offered sacrifices to Dahushen in Chaoyang and wrote three sacrificial articles that prayed for rain and shine (). In the sixteenth century, the Temple of Mercy and Blessing (Huifu Miao 惠福廟, renamed Dahushen Miao later) was viewed as the place that Han Yu visited and prayed for weather. Local officials willingly followed in his footsteps. The Chaoyang magistrate Huang Yilong successfully prayed for rain many times and initiated the rebuilding of Huifu Miao (). When and why the worship of Han Yu began in Hubian are unknown. It is possible that Han Yu was worshipped as a secondary deity in the Huifu Miao temple first, and that a new temple was then built. Worship here possibly started before the eighteenth century. In an inscription dated 1718, Han Yu is called Changli Hanye 昌黎韓爺32, and is used to emphasize the orthodoxy of Dahushen Miao with regard to the protection of temple estates.33 The Han Wengong Temple is currently being rebuilt and extended. The statue of Han Yu has been put in a room nearby (see Figure 2). The third temple is also small and was built before the middle of the nineteenth century. It is located in Laoxiang 荖巷, which is in countryside that was once planted with betel (lao 荖). Around 1850, the betel was replaced by mandarin oranges since the habit of chewing betel nuts changed. During the Republic, it was said that Han Yu taught Chaozhou people to eat betel in order to resist miasma, and that villagers built a temple devoted to Han Yu out of gratitude. In the temple, the statue of Han Yu holds a piece of betel (). The temple was revived in 1988. The above three temples devoted to Han Yu are small in scale and similar to the tutelary temple. In another two temples, Han Yu was worshipped as a secondary deity. In Jinzhou village, the Ancient Temple of Jinzhou (Jinzhou Gumiao) is devoted to the Eldest King of Three Mountains, as the most important deity (dalaoye 大老爺), and more than ten deities as secondary deities. On the right side, six small wooden statues are in a wooden niche. The statues of Han Yu and Han Xiangzi are slightly larger and set in the middle (see Figure 3). Local villagers currently know little about the worship of Han Yu and do not have any specific ceremony or ritual for Han Yu. Existent inscriptions show that the temple was rebuilt in 1922 and revived in 1992. The last is a shrine inside the Temple of Numinous Mountain, which was first built by Monk Dadian. After his death, Dadian became the primary figure of worship in the temple. The shine is beside the shrine of Patriarch Dadian and is devoted to Patriarch Sanping (Sanping Zushi 三坪祖師, also known as Monk Guangji). Han Yu is a secondary deity in the shrine (see Figure 4). It is currently unknown when the worship of Han Yu emerged in this temple.34 It was said that Han Yu visited the Temple of Numinous Mountain in order to meet Monk Dadian and left his clothes as a parting gift since he failed to meet Dadian. During the reign of Chenghua 成化 (1465–1487), villagers built the Pavilion of Leaving Clothes (Liuyi Ting 留衣亭) on the left of the temple, and the Chaoyang magistrate Wu Gu 吳穀 ordered them to create the statue of Han Yu in the pavilion in memory of the friendship between Han Yu and Dadian (). The pavilion has been repaired and reconstructed many times (see Figure 5).

Figure 2.

The statue of Han Yu in Hubian.

Figure 3.

The statues of Han Yu (right) and Han Xiangzi in Jinzhou.

Figure 4.

The statue of Han Yu (left) in the Temple of Numinous Mountain.

Figure 5.

The Pavilion of Leaving Clothes, rebuilt in 1985 (all photographed by the author).

5. Official Support and Popular Religion: Preliminary Conclusions

The development of the Han Yu belief can be summarized into three aspects. First, the Han Yu temples were built in the prefectural seat and most county seats over a period of nearly a thousand years. In the year 999, Chaozhou controller-general Chen Yaozuo first built a temple devoted to Han Yu in the center of Chaozhou. This temple was typical of orthodox sacrifices and was continuously supported by local officials, particularly the supreme governors of Chaozhou. From the Song dynasty to the Republic, the temple was relocated twice and was renovated or rebuilt more than twenty-eight times. Local officials attached great importance to the Han Wengong Temple and rebuilt it once destroyed. Its continuity became a kind of political achievement and a reflection of local developments. From the sixteenth century, the Han Yu belief entered a new stage and was transmitted to county seats. This transmission was slow, and only seven temples were established in three hundred years. Second, these Han Yu temples laid a foundation for the belief in academies. In 1243, the Chaozhou prefect Zheng Liangchen founded the first academy that offered sacrifices to Han Yu, which started another form of the Han Yu belief in Chaozhou. It was from the seventeenth century that many academies were established and offered sacrifices to Han Yu; in addition, the worship of Han Yu was performed in preexistent academies. The new development of temples and academies was related to national polices that were affected by Confucian fundamentalism and centered around the orthodoxy of sacrifices. Lastly, the worship of Han Yu came into being among the masses, but its spread was considerably limited. Only several small temples or shrines were discovered. Although local officials and the literati spared no efforts in supporting the Han Yu belief, Han Yu failed to develop into a powerful and influential deity in Chaozhou.

As shown in the article, local officials and the literati supported the rise of the Han Yu belief in Chaozhou. The Han Yu belief was a typical official (or orthodoxy) belief promoted by local officials. We know that they usually and mainly developed orthodox sacrifices in opposition to “illicit sacrifices”. From the Song dynasty onward, the position of Han Yu reached a peak, and Han Yu himself became a cultural symbol and cultural resource. Local officials followed Han Yu to govern Chaozhou and viewed him as a role model. They established and developed the Han Yu temples to express their sense of admiration and accomplish political achievements. The Han Yu belief was an orthodoxy and became an excellent way to educate Chaozhou people. From the sixteenth century, local officials began to construct temples in affiliated counties. In the eighteenth century, temples were built in most counties. The development of the Han Yu temples relied on constant official support, and therefore the belief was able to continue without miracles. In the meantime, Han Yu was depicted as a pioneering figure in the history of Chaozhou education and became a significant deity among the literati. The worship of Han Yu in academies was an extension of the Han Yu temples. Most academies were built or began to offer sacrifices to Han Yu after the middle of the eighteenth century. The worship of Han Yu in academies was caused by Han Yu’s own position as an outstanding figure in the domain of literature and Neo-Confucian teachings. Han Yu was a mentor for the literati and was transformed into a deity of imperial civil examinations, but this transformation was not so successful.

Among the masses, the image of Han Yu became increasingly secularized. As an official, Han Yu helped the Chaozhou people. In many stories, Han Yu’s contribution was based on the help of his nephew Han Xiangzi and Monk Dadian. As a deity, Han Yu was low in rank, like a tutelary god. Only a few temples were built, and these were small in scale. Local officials and the literati raised Han Yu’s popularity and promoted the belief, but the belief was never widespread in the Chaozhou region. This demonstrates that local officials and the literati focused on different aspects of the Han Yu belief. They emphasized that Han Yu was both an admirable official and outstanding mentor. They were never concerned with miracles and always stressed the orthodoxy of the Han Yu belief. For example, local officials replaced the wood statues of Han Yu and Zhao De with wood tablets in the middle of the Ming dynasty since the statues were not consistent with Confucian rites (). When unsuitable behaviors and activities emerged, they criticized and rectified them. What they neglected and what they rectified were what the masses were really interested in. Meanwhile, what they were concerned with and endeavored to achieve somewhat hampered the spread of the Han Yu belief among the masses.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangdong Provincial Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation (Guangdong sheng sheke) No. GD21TW04-02 and Shantou University No. STF21019.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For example, cults of snakes and cults of Kings of Three Mountains (Sanshan Guowang 三山國王). In Chaozhou, cults of snakes at least can be dated back to the Song. In the city of Chaozhou, the Temple of Green Dragon (Qinglong Miao 青龍廟) was built before the Ming and was devoted to snakes. From the seventeenth century, the main deity was gradually transformed into a governor (taishou 太守) named Wang Kang 王伉 and was listed among official sacrifices (). In another example, many legends and miracles were created to constrcuted the orthodoxy of Kings of Three Mountains that were widespread deities in Chaozhou. Han Yu was used as a source of orthodoxy from the Yuan dyansty. The literati argued that Han Yu offered sacrifices to the Kings in his term (). |

| 2 | In this article, Chaozhou is a cultural region, depending on its geographic surroundings, a relatively stable pattern of administrative division, and an evolving regional culture. The Chaozhou region is located in the southeastern coastal region of China and contains the second largest plain in Guangdong, i.e., Chaoshan pingyuan 潮汕平原. In administrative division, the region primarily referred to Chaozhou, Chaozhoulu 潮州路, or Chaozhoufu 潮州府 from the Sui 隋 dynasty to the Republic. Its center was the Chaozhou city and located in Haiyang 海陽. The scope of Chaozhou kept rather stable, but the administrative division changed along with the rising population and the increasing infiltration of state power. From the sixteenth century, many new counties were set up. In 1208, Chaozhou governed Haiyang, Chaoyang 潮陽, and Jieyang 揭陽 counties; in 1582, Chaozhoufu 潮州府 governed Haiyang, Chaoyang, Jieyang, Chengxiang 程鄉, Raoping 饒平, Huilai 惠來, Dabu 大埔, Chenghai 澄海, Puning 普寧, and Pingyuan 平遠 counties. In 1820, Chaozhoufu governed nine counties and one subprefecture (ting 廳): Haiyang, Chaoyang, Jieyang, Raoping, Huilai, Dabu, Chenghai, Puning, Fengshun 豐順, and Nan’ao ting 南澳廳. In the stable region, a distinctive regional culture was evolving and reflected in many aspects, such as Chaozhou dialect as a primary language and similar popular religion in different counties. Cf. (). |

| 3 | An early version was published in 1993. |

| 4 | Ding Yunyuan was relegated to the Chaozhou prefect because of his earnest remonstrances (). |

| 5 | Fang Gonghui, Zengxiu Hanshan Changli Ci ji 增修韓山昌黎祠記 (1894) (). |

| 6 | Liu Zixing, Chongxiu Han Wengong Miao beiji 重修韓文公廟碑記 (1575) (). |

| 7 | Zeng Huagai 曾華蓋, Chongxiu Hangong Ci ji Guangji qiao beiji 重修韓公祠及廣濟橋碑記 (1681) (). |

| 8 | Cf (; ; , ). |

| 9 | Huang Yilong, Xinjian Hanci ji 新建韓祠記 (1572) (). |

| 10 | The Twin Loyalty refer to Zhang Xun 張巡 and Xu Yuan 許遠 who sacrificed their lives for guarding Suiyang 睢陽 in the An Shi rebellion (755–763). Since Han Yu wrote an essay to defend Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan in the Tang court and supported sacrifices to them, the court first built the Temple of Twin Loyalty in Suiyang. Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan became a symbol of loyalty and righteousness as deities. From the end of the Song dynasty, the belief of Twin Loyalty was transmitted to Chaoyang and experienced a long period of localization in the Chaozhou region. In the process of localization, the literati used Han Yu to exphasize the orthodoxy of Twin Loyalty in Chaozhou and strengthen the connection between the Twin Loyalty and Chaozhou. The sixteenth century witnessed that the Twin Loyalty became significant deities in the Chaoyang city and protecting deities of many villages and clans. By the nineteenth century, more than seventy temples were established for the Twin Loyalty. Cf. (; ; ; ). Unlike the Han Yu belief, the belief of Twin Loyalty is active and influenial currently. |

| 11 | Lin Dachun reached the rank of Zhejiang’s 浙江 Education Intendant (tidu xuedao 提督學道). In 1569, he was dismissed from office and returned to Chaoyang. |

| 12 | Lin Dachun described, when he took office in Suiyang and visited battlefields where Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan used to fight, he enquired the aged about the Twin Loyalty’s coming to Chaoyang; the aged said, the Twin Loyalty came to Chaoyang to reward Han Yu’s defence in court since Han Yu was relegated to Chaozhou. See Lin Dachun, Chongjian Lingwei Miao ji 重建靈威廟記 (1565) (). This experience was close to a marvelous miracle. More miracles about Han Yu and the Twin loyalty in Chaozhou, see (). Li Dachun actively participated in the construction of Hanshan Academy, writing calligraphy for plaques in 1577 and 1583 (). |

| 13 | See Chen Zhi’ang 陳之昂, Dongshan sixian shuo 東山四賢説 (1648) (). There was a temple devoted to Wen Tianxiang 文天祥 (1236–1283) and constructed in 1497 in the East Mountain (). |

| 14 | See Cf (; ; ; ; ). |

| 15 | Han Yu, Chaozhou qing zhi xiangxiao die 潮州請置鄉校牒 (). |

| 16 | Lin Xiyi 林希逸, Chaozhou chongxiu Hanshan Shuyuan ji 潮州重修韓山書院記 (1269) (); (). |

| 17 | Long Weilin, Hanshan Shuyuan beiji 韓山書院碑記 (1733), erected in Hanshan Normal University currently. |

| 18 | Cf “Lidai Chaozhou de sihan shuyuan;” Wu Rongqing ed., Gudai Chaozhou jiaoyu beike ziliao ji 古代潮州教育碑刻資料集 (2012, unpublished); Cheng Huan 程煥, Gaijian Hangong Ci beiji 改建韓公祠碑記 (1785); Dabu Xianzhi. |

| 19 | The tablet is stored in the backyard of Sanrao 三饒 Township Government. |

| 20 | Oaks were distributed in the north of China, such as Han Yu’s hometown. |

| 21 | Wang Dabao 王大寶 (1094–1170), Hanmu zan 韓木讚 (). |

| 22 | Dadian was a reputable monk of the Zen sect in the Chaozhou region. He established the Temple of Numinous Mountain (Lingshan Si 靈山寺) in Chaoyang and passed his teachings to more than a thousand disciples. Dadian had a relationship with Han Yu, which became a dispute among descendants (). |

| 23 | In history, Guangji was a disciple of Dadian. |

| 24 | Li Wan and another servant, Zhang Qian 張千, were secondarily worshiped in the Temple of Han Wengong in Hanshan at least from the Qing. |

| 25 | A new script was created in 1988. Han Yu acted as a righteous official to punish wizards and corrupt officials in Chaozhou. See Shi Qizhou 施其洲, Han Yu Chu E 韓愈除鱷, printed by Raopingxian Wenhuaju 饒平縣文化局, 1988. |

| 26 | Chen Yisong 陳一松, Chongxiu Guangji qiao ji 重修廣濟橋記 (1578) (). Another record: “for the construction of the bridge, the aged said, Changli offered sacrifices to the river, and the river dried up.” (先是此橋之建,故老相傳昌黎祭河,河為之涸) See Lin Xichun, Chongxiu Hanci beiji (1609), erected in the Temple of Han Wengong currently. |

| 27 | In an investigation of more than 300 villages in Puning, more than 500 temples and 150 deities were discovered, but the belief of Han Yu was not discovered (). |

| 28 | In Suzhou 蘇州, the Chazhou Guild (Chaozhou Huiguan 潮州會館) began to offer sacrifices to Han Yu in 1708. See Chaozhou Huiguan ji 潮州會館記 (1784) (). |

| 29 | I visited hundreds of villages and thousands of temples in this region in recent ten years. |

| 30 | At least from the seventeenth century, it was said that Han Yu built the North Embankment of Chaozhou (). |

| 31 | There were Yangshan 陽山, Raosha 饒砂, Gudi 古堤, Houyangdi 後洋堤, Jishui 急水, Gumei 古美, Neikeng 內坑, and Xianmei 仙美. |

| 32 | Chaozhou people usually called deities laoye 老爺 which refers to both male and female deities. For Han Yu, local people can call him Hanye. |

| 33 | Lianming xianzhu laoye Zhi shijin 廉明縣主老爺支示禁, erected in the front of the Han Wengong Temple currently. |

| 34 | An inscription, dated 1521 and discovered in recent years, records that the Hong 洪 family supported the building of Hanci in 949 to commemorate the event of leaving clothes. See Li Chaoyuan 李朝元, Chongxiu Qibei Hongshi shizhu Citang ji 重修歧北洪氏施主祠堂記 (). The inscription is erected in the Temple of Numinous Mountain currently. The record contradictes the description in local gazetteers, and it needs more histiorical resources to clarify this question. |

References

- Bian, Liang 卞梁, and Chenxi Lian 連晨曦. 2020. Chao Tai Han Yu xinyang bijiao yanjiu 潮台韓愈信仰比較研究 [A Comparative Study of Hanyu Belief in Chaozhou and Taiwan]. Hanshan Shifan Xueyuan Xuebao 韓山師範學院學報 Journal of Hanshan Normal University 41: 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Liangjun 卞良君. 2013. Gudai xiaoshuo zhong Han Yu gushi de yanbian ji Han Yu xingxiang de chuangzao 古代小說中韓愈故事的演變及韓愈形象的創造 [The Evolution of the Story of Han Yu in Ancient Novel and the Creation of Han Yu’s Image]. Guangdong Shehui Kexue 廣東社會科學 Social Sciences in Guangdong 161: 152–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Liangjun. 2014. Qingdai daoqing, baojuan zhong Han Yu xingxiang de yanbian jiqi lishi wenhua jiazhi 清代道情、寶卷中韓愈形象的演變及其歷史文化價值 [The Evolution of Han Yu’s Image in the Chanting Folk Tales during the Qing Dynasty and Its Historical and Cultural Value]. Zhongzhou Xuekan 中州學刊 Academic Journal of Zhongzhou 206: 152–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Liangjun. 2015. Daoqing, Baojuan zhong de Han Yu gushi jiqi dui xiangguan difang xiqu de yingxiang 道情、寶卷中的韓愈故事及其對相關地方戲曲的影響 [Han Yu’s Stories in the Chanting Folk Tales and Their Influence on Related Local Operas]. Xueshu Luntan 學術論壇 Academic Forum 295: 101–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Peter K. 1992. “This Culture of Ours”: Intellectual Transitions in T’ang and Sung China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Zemin 蔡澤民, ed. 1988. Chaozhou Minjian Gushi Jicheng Ziliaoben 潮州民間故事集成資料本 [Data Book of the Collection of Chaozhou Folktale]. Chaozhou: Chaozhoushi Minjian Wenxue Santao Jicheng Bianzuan Weiyuanhui. [Google Scholar]

- Chaozhoushi Minjian Wenxue Santao Jicheng Bianweihui 潮州市民間文學三套集成編委會. 1988. Xianfo Zaoqiao: Chaozhou Minjian Gushi Xuan 仙佛造橋:潮州民間故事選 [Immortals and Buddha Building Bridge: Selections of Chaozhou Folktale]. Fuzhou: Haixia Wenyi Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chunsheng 陳春聲. 2001. Zhengtongxing, difanghua yu wenhua de chuangzhi: Chaozhou minjian shen xinyang de xiangzheng yu lishi yiyi 正統性、地方化與文化的創制:潮州民間神信仰的象徵與歷史意義 [The Symbolic and Historical Significance of Popular Cults in Chaozhou]. Shixue Yuekan 史學月刊 Journal of Historical Science 1: 123–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chunsheng. 2003. “Zhengtong” shenming difanghua yu diyu shehui de jiangou: Chaozhou diqu Shuangzhonggong chongbai de yanjiu “正統”神明地方化與地域社會的建構:潮州地區雙忠公崇拜的研究 [The Localization of Orthodoxy Deities and Construction of Local Society: Study on Shuangzhong Cults in the Chaozhou Region]. Hanshan Shifan Xueyuan Xuebao 韓山師範學院學報 Journal of Hanshan Normal University 24: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chunsheng. 2021. Difang Gushi Yu Guojia Lishi: Hanjiang Zhongxiayou Diyu De Shehui Bianqian 地方故事與國家歷史:韓江中下游地域的社會變遷 [Local Stories and National History: Social Changes in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Han River]. Beijing: Shenghuo Dushu Xinzhi Sanlian Shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Meihu 陳梅湖, ed. 2007. Nan’ao Xianzhi 南澳縣志 [Nao’ao Gazetteer]. Taiyuan: Shanxi Neibu Tushu. First published 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Meihu, ed. 2009. Raoping Xianzhi Buding 饒平縣志補訂 [Supplement to Raoping Gazetteer]. Raoping: Raopingxian Difangzhi Bangongshi. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shuzhi 陳樹芝, ed. 1991. Jieyang Xianzhi 揭陽縣志 [Jieyang Gazetteer]. Beijing: Shumu Wenxian Chubanshe. First published 1731. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Taiyu 陳汰餘, ed. 2005. Zhanglin Xiangtu Zhilüe 樟林鄉土志略 [Brief History of Zhanglin]. Chenghai: Chenshi Lishi Wenhua Yanjiu Choubeihui. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yunjin 陳運金, ed. 1987. Zhongguo Minjian Wenxue Jicheng Guangdong Juan Chaoyangxian Ziliaoben 1 中國民間文學集成廣東卷潮陽縣資料本1 [Data Book of the Collections of Chinese Folk Literature · Guangdong Province · Chaoyang County]. Chaoyang: Chaoyangxian Minjian Wenxue Santao Jicheng Bianzuan Lingdao Xiaozu. [Google Scholar]

- Chongkan Jiujie Jindeng Quanbu 重刊救劫金燈全部 [Golden Lamp for Saving People from Calamity]. 1915. Chaozhou: Lin Wenzai lou 林文在樓.

- Clart, Philip. 1996. The Ritual Context of Morality Books: A Case-Study of a Taiwanese Spirit-Writing Cult. Ph.D. dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Clart, Philip. 2008. The Relationship of Myth and Cult in Chinese Popular Religion: Some Remarks on Han Xiangzi. Xingda Zhongwen Xuebao 興大中文學報 Journal of Chinese Literature 23: 479–514. [Google Scholar]

- Duara, Prasenjit. 1988. The Myth of Guandi, Chinese God of War. The Journal of Asian Studies 47: 778–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Chun-wu 范純武. 2003. Shuangzhong Chongsi Yu Zhongguo Minjian Xinyang 雙忠崇祀與中國民間信仰 [Chinese Popular Religion and Shuangzhong Cults]. Ph.D. dissertation, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, China. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhoufu 葛洲甫, ed. 1967. Fengshun Xianzhi 豐順縣志 [Fengshun Gazetteer]. Taipei: Chengwen Chubanshe. First published 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Han 關漢, and Xuan Wei 韋軒, eds. 1982. Guangdong Minjian Gushi Xuan 廣東民間故事選 [Selections of Guangdong Folktale]. Guangzhou: Huacheng Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Chunzhen 郭春震, ed. 1991. Chaozhou Fuzhi 潮州府志 [Chaozhou Gazetteer]. Beijing: Shumu Wenxian Chubanshe. First published 1547. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Zizhang 郭子章, ed. 2003. Chaozhong Zaji 潮中雜紀 [Records of Chaozhou]. Chaozhou: Chaozhoushi Difangzhi Bangongshi. First published 1585. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Yu 韓愈. 1986. Han Changli Wenji Jiaozhu 韓昌黎文集校注 [Annotations on Han Changli’s Collected Works]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Valerie. 1990. Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127–1276. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell, Robert M. 1982. Demographic, Political, and Social Transformations of China, 750–1550. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 42: 365–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Chanjuan 何嬋娟. 2018. Qianxi Chaozhou shike yu Han Yu de shenhua xianxiang 淺析潮州石刻與韓愈的神化現象 [A Brief Analysis of Chaozhou Stone Inscription and the Deification of Hanyu]. Guangxi Jiaoyu Xueyuan Xuebao 廣西教育學院學報 Journal of Guangxi College of Education 155: 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ting 黃挺, and Zhanshan Chen 陳占山. 2001. Chaoshan Shi 潮汕史 [History of Chaoshan]. Guangzhou: Guangdong Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, Robert P. 1986. Statesmen and Gentlemen: The Elite of Fu-Chou Chiang-Hsi, in Northern and Southern Sung. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, Robert P. 2002. Way and Byway: Taoism, Local Religion, and Models of Divinity in Sung and Modern China. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiangsusheng Bowuguan 江蘇省博物館, ed. 1959. Jiangsusheng Ming Qing Yilai Beike Ziliao Xuanji 江蘇省明清以來碑刻資料選集 [Selections of Jiangsu Inscriptions Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Beijing: Shenghuo Dushu Xinzhi Sanlian Shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman, Terry F. 1994. A God’s Own Tale: The Book of Transformations of Wenchang, the Divine Lord of Zitong. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guoping 李國平. 2017. Song Yuan yijiang Chaozhou diqu Shuangzhong xinyang de dili fenbu 宋元以降潮州地區雙忠信仰的地理分佈 [Geographical Distribution of Twin Loyalty Belief in the Chaozhou Area since the Song and Yuan Dynasties]. Zhongguo Lishi Dili Luncong 中國歷史地理論叢 Journal of Chinese Historical Geography 122: 136–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guoping. 2018a. Difang miaoyu yu quyu wenhua: Yi Mingdai yi jiang Shuangzhong xinyang zai Chaozhou zhongxin chengqu de chuanbo wei li 地方廟宇與區域文化:以明代以降雙忠信仰在潮州中心城區的傳播為例 [Local Temples and Regional Cultural on the Transmission of Chaozhou Twin Loyalty Belief]. Zhongzheng Lishi Xuekan 中正歷史學刊 Chung Cheng Journal of History 21: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guoping. 2018b. Guangdong Chaoyangxian Shuangzhong xinyang yuanqi tanwei 廣東潮陽縣雙忠信仰源起探微 [The Origin of Shuangzhong belief in Chaoyang County, Guangdong Province]. Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教學研究 Religious Studies 120: 256–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guoping. 2018c. Minjian xinyang qiyuan chuanshuo de shanbian: Yi Chaozhou Shuangzhong xinyang weili 民間信仰起源傳說的嬗變:以潮州雙忠信仰為例 [The Evolution of Original Legends of Popular Religion—With Chaozhou Twin Loyalty Belief as an Example]. Shantou Daxue Xuebao 汕頭大學學報 Journal of Shantou University 34: 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guoping. 2023a. Spirit-Writing Cults in the Chaozhou Region Between 1860 and 1949: Local Religion and Translocal Religious Movements. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guoping. 2023b. The Spirit-writing Movement in the Chaozhou Region: Response to Modern Crises (1840–1949). Religions 14: 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Laitao 李來涛. 1999. Longmenguan Hanci de cangsang 龍門關韓祠的滄桑 [History on Longmenguan Hanci]. Chaozhou Wenshi Ziliao 潮州文史資料 Chaozhou Cultural and Historical Materials 19: 150–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhixian 李志賢. 2012. Tangren Songshen: Han Yu zai Chaozhou de shenhua yu shenhua 唐人宋神:韓愈在潮州的神話與神化 [A Man in the Tang Dynasty but a God in the Song Dynasty: Myths and Deification of Han Yu in the Sate of Chao]. Shanxi Shifan Daxue Xuebao 陝西師範大學學報 Journal of Shaanxi Normal University 41: 166–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Dachuan 林大川. 2000. Hanjiang Ji 韓江記 [Anecdotal Account of Hanjiang]. Xi’an: Zhongzhou Guji Chubanshe. First published 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Dachun 林大春, ed. 1963. Chaoyang Xianzhi 潮陽縣志 [Chaoyang Gazetteer]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Shudian. First published 1572. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Juncong 林俊聰, ed. 2004. Chaoshan An Si (Shantoushi) 潮汕庵寺(汕頭市) [Chaoshan Temples]. Guangzhou: Huacheng Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Quanhua Xinbian 勸化新編 [New Collection for Exhorting Transformation]. 1922. Shantou: Minglixuan.

- Rao, Zongyi. 2009a. Chaozhou Han Wengong Ci kao 潮州韓文公祠考 [Study on Chaozhou Han Wengong Ci]. In Rao Zongyi Ershi Shiji Xueshu Wenji Juanjiu (Xia) 饒宗頤二十世紀學術文集·卷九(下)[Rao Zongyi’s 20th Century Academic Collection]. Beijing: Zhongguo Renmin Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Zongyi 饒宗頤. 2009b. Guangji qiao zhi 廣濟橋志 [Gazetteer of Guangji qiao]. In Rao Zongyi Ershi Shiji Xueshu Wenji Juanjiu (Shang) 饒宗頤二十世紀學術文集·卷九(上)[Rao Zongyi’s 20th Century Academic Collection]. Beijing: Zhongguo Renmin Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, Anna M. 2015. One Who Knows Me: Friendship and Literary Culture in Mid-Tang China. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Wenzao 唐文藻, ed. 2009. Chaoyang Xianzhi 潮陽縣志 [Chaoyang Gazetteer]. Guangzhou: Lingnan Meishu Chubanshe. First published 1819. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Haar, Barend J. 2017. Guan Yu: The Religious Afterlife of a Failed Hero. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Dai 王岱, ed. 2004. Chenghai Xianzhi 澄海縣志 [Chenghai Gazetteer]. Chaozhou: Chaozhoushi Difangzhi Bangongshi. First published 1686. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jianchuan 王見川, and Qingsheng Pi 皮慶生. 2010. Zhongguo Jinshi Minjian Xinyang: Song Yuan Ming Qing 中國近世民間信仰:宋元明清 [Chinese Popular Religion in Early Modern Period: Song Yuan Ming Qing]. Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lianhua 王蓮華. 2009. Han Yu Minjian Xingxiang Kaolun: Yi Suwenxue Wei Zhongxin 韓愈民間形象考論——以俗文學為中心 [A Study of the Images of Han Yu in Folklore——An Investigation Centered on the Popular Literature of China]. Master’s thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, James L. 1985. Standardizing the Gods: The Promotion of T’ien Hou (Empress of Heaven) Along the South China Coast, 960–1960. In Popular Culture in Late Imperial China. Edited by David Johnson, Andrew J. Nathan and Evelyn S. Rawski. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, pp. 292–324. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Daorong 吳道鎔, ed. 1967. Haiyang Xianzhi 海陽縣志 [Haiyang Gazetteer]. Taipei: Chengwen Chubanshe. First published 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Rongqing 吳榕青. 2009. Lidai Chaozhou de si Han shuyuan: Yi beike ziliao wei zhongxin 歷代潮州的祀韓書院——以碑刻資料為中心 [Academies in Memory of Han Yu in History in Chaozhou: Based on Tablet Data]. Shantou Daxue Xuebao 汕頭大學學報 Journal of Shantou University 25: 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Rongqing. 2011. Chaozhou Hanshan Shuyuan de shijian niandai, yuanzhi ji yange zaitan: Yi beike ziliao wei zhongxin 潮州韓山書院的始建年代、院址及沿革再探——以碑刻資料為中心 [Re-analysis of the Foundation Year, Academic Site and Evolution of Chaozhou Hanshan Academy——Focused on the Inscriptions Materials]. Hanshan Shifan Xueyuan Xuebao 韓山師範學院學報 Journal of Hanshan Normal University 32: 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Rongqing. 2015. Chaozhou Qinglong (Anji) Miao de xinyang yuanyuan jiqi bianqian 潮州青龍(安濟)廟的信仰淵源及其變遷 [The Origin and Changing of the Belief in Qinglong (Anji) Temple in Chaozhou]. Wenhua Yichan 文化遺產 Cultural Heritage 2: 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Rongqing. 2019. Hanshan Shuyuan Shigao 韓山書院史稿 [History of Hanshan Academy]. Shenzhen: Shenzhen Baoye Jituan Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Rongqing 吳榕青, and Guoping Li 李國平. 2023. “Han Yu zai Chaozhou” de lishi yu xiangxiang: Yi Song Yuan Sanyang Zhi, Sanyang Tuzhi jizai wei zhongxin “韓愈在潮州”的歷史與想象——以宋元《三陽志》《三陽圖志》記載為中心 [History and Imagination on “Han Yu in Chaozhou”——Centered around Records of Song’ and Yuan’s Sanyang zhi and Sanyang tuzhi]. Chaoxue Yanjiu 潮學研究 Chaozhou-Shantou Culture Research 27: 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Tiesheng 向鐵生, and Yuxuan Wu 吳宇軒. 2018. Tang Wudai biji xiaoshuo zhong Han Yu gushi de zhuti wenhua chengyin ji jiazhi 唐五代筆記小說中韓愈故事的主題、文化成因及價值 [The Theme, Cultural Cause and Value of Han Yu’s Story in the Literary Sketches of the Tang and Five Dynasties]. Fujian Shifan Daxue Xuebao 福建師範大學學報 Journal of Fujian Normal University 212: 109–17. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Linzhi 蕭麟趾, ed. 1974. Puning Xianzhi 普寧縣志. Taipei: Chengwen Chubanshe. First published 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Shaosong 蕭少宋. 2009. Chaozhou Gece Yanjiu 潮州歌冊研究 [Study of Chaozhou Songbook]. Ph.D. dissertation, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Xinzao Song Hanyi Quange 新造送寒衣全歌 [Newly Complete Songbook on Giving Winter Clothing]. n.d. Before 1949. Chaozhou: Wansheng ji.

- Yang, Erzeng 楊爾曾. 2007. The Story of Han Xiangzi: The Alchemical Adventures of a Daoist Immortal. Translated and Introduced by Philip Clart. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Guo’an 楊國安. 2006. Songdai Hanxue Yanjiu 宋代韓學研究 [Research on the Song Dynasty’s Han Study]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yongle Dadian 永樂大典 [Yongle Encyclopedia]. 1986. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.

- Zao Fuqiao 造浮橋 [Building the Pontoon Bridge]. n.d. Before 1949. Chaozhou: Li Wanli.

- Zeng, Chunan 曾楚楠, ed. 2015. Han Yu Zai Chaozhou 韓愈在潮州 [Han Yu in Chaozhou]. Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Chunan, ed. 2023. Chaozhoushi Wenwu Zhi 潮州市文物志 [Records on Chaozhoushi Cultural Relics]. Guangzhou: Huacheng Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Wei 趙葦. 2022. Beisong Mingchen Chen Yaozuo Yanjiu 北宋名臣陳堯佐研究 [Study on Chen Yaozuo, a Famous Minister in the Northern Song Dynasty]. Master’s thesis, Heibei University, Baoding, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Changshi 鄭昌時. 1995. Hanjiang Wenjianlu 韓江聞見錄 [Records on Hanjiang]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. First published 1824. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shuoxun 周碩勳, ed. 1967. Chaozhou Fuzhi 潮州府志 [Chaozhou Gazetteer]. Taipei: Chengwen Chubanshe. First published 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Haibin 朱海滨. 2008. Jisi Zhengce Yu Minjian Xinyang Bianqian: Jinshi Zhejiang Minjian Xinyang Yanjiu 祭祀政策與民間信仰變遷:近世浙江民間信仰研究 [Sacrificial Policies and Changes in Popular Religion: A Study of Zhejiang Popular Religion in Early Modern Period]. Shanghai: Fudan Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).