Religious Nones and Spirituality: A Comparison between Italian and Uruguayan Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Socioreligious Challenges of Defining Nones

Scholars invented the category and then put people (and other phenomena) in it; we should not forget that it is a conceptual category. It was initially useful, and continues to be useful, in majority religious environments. But it is still an invention of scholars to help us theorize, identify, and measure a specific subset of populations around the world.

In some ways, the religiously unaffiliated are the most difficult groups to characterize in American society. At least Christians can agree that the Bible is a sacred text and that a worship service should contain some songs, Scripture reading, and prayer. The religiously unaffiliated are not a cohesive group in the same way. The reality is that the only thing that truly binds them together is the fact that they might all check the same box on the survey form.

2.2. Being A None: Demographics, Political Orientation, and Spiritual Practices

These are Nones who claim no religious affiliation but who nonetheless profess a belief in a God, a higher power, or life force; who engage in spiritual practices like prayer, meditation, or yoga; and who may, periodically at least, attend services of traditional religious groups.

2.3. Nones in Cross-National Study of Italy and Uruguay

2.3.1. Spirituality of Young Nones in Italy

When we investigate the religiousness of the Italian young people, the main question is not so much with which religion they identify themselves, considering the prevalence of Catholicism in the national territory, but rather describing the different modalities of practicing and believing, that they often live in a free and autonomous way in relation to such identification.

The positions of young Italians engaged in spiritual itineraries outside organized churches, and even those of ‘Neither religious nor spiritual’ youth, are critically and reflexively built on the basis of the dominant cultural model of Church religion: they refuse the latter’s authority and doctrinal dogmatism, but it is certainly still the reference prototype as far as religion and theological conceptions are concerned.

As we have seen, the dissolution of a metaphysical idea of religious subjects leads to the consideration of spiritual identity as a field of possibilities and limits contemporaneously belonging to different social worlds: working, residential, cultural, sporting and also religious. This multiple identity is significantly related to religious lifestyles which, insofar as they are real experiences of the self in various social situations, and their turn open, differentiated and reflexive.

2.3.2. Studying Religious Nones’ Spirituality in Uruguay

3. Method

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Measure

3.4. Participants

4. Results

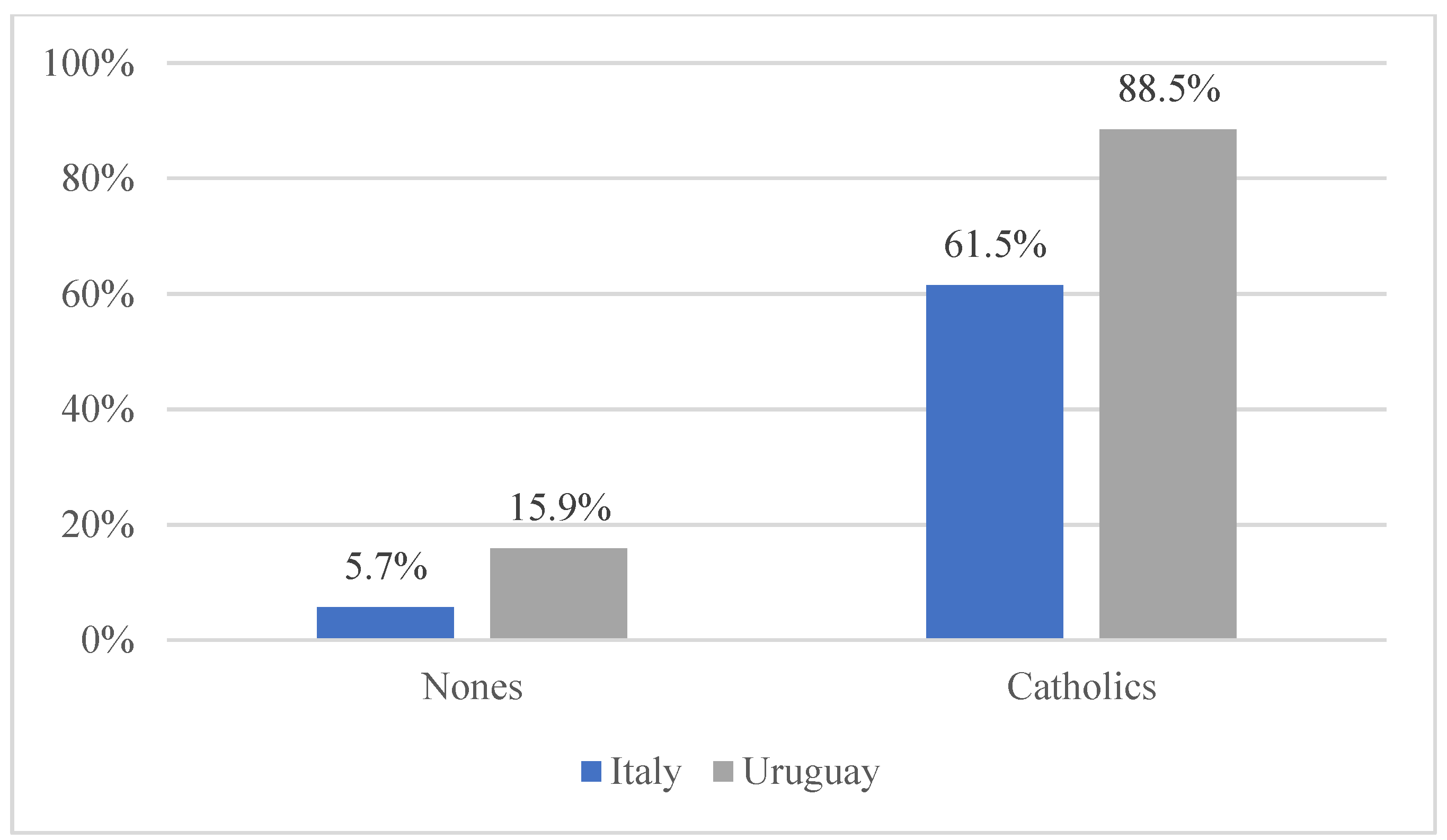

4.1. Nones: Sociodemographic Characteristics, Political Views, and Criticism toward Religion

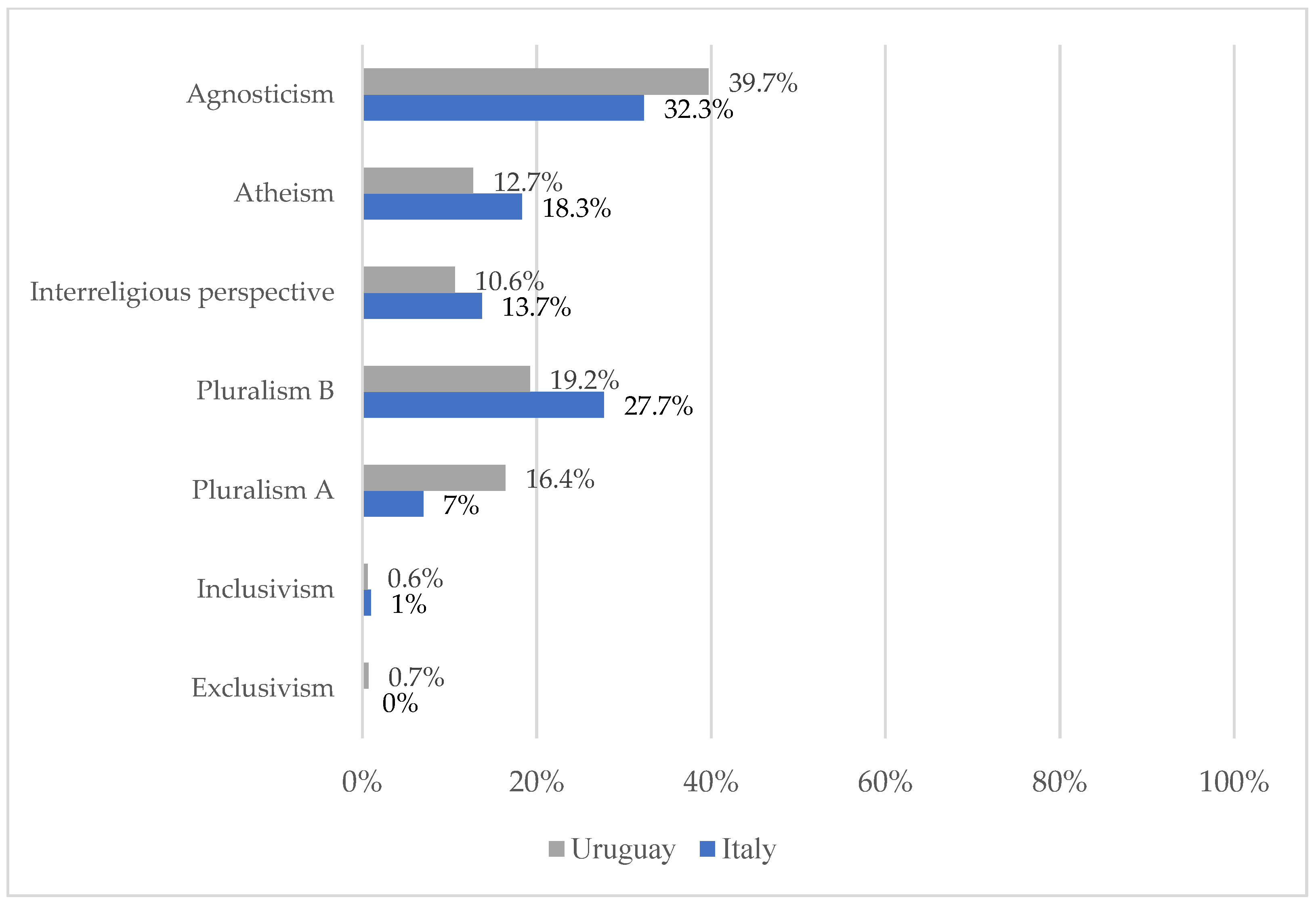

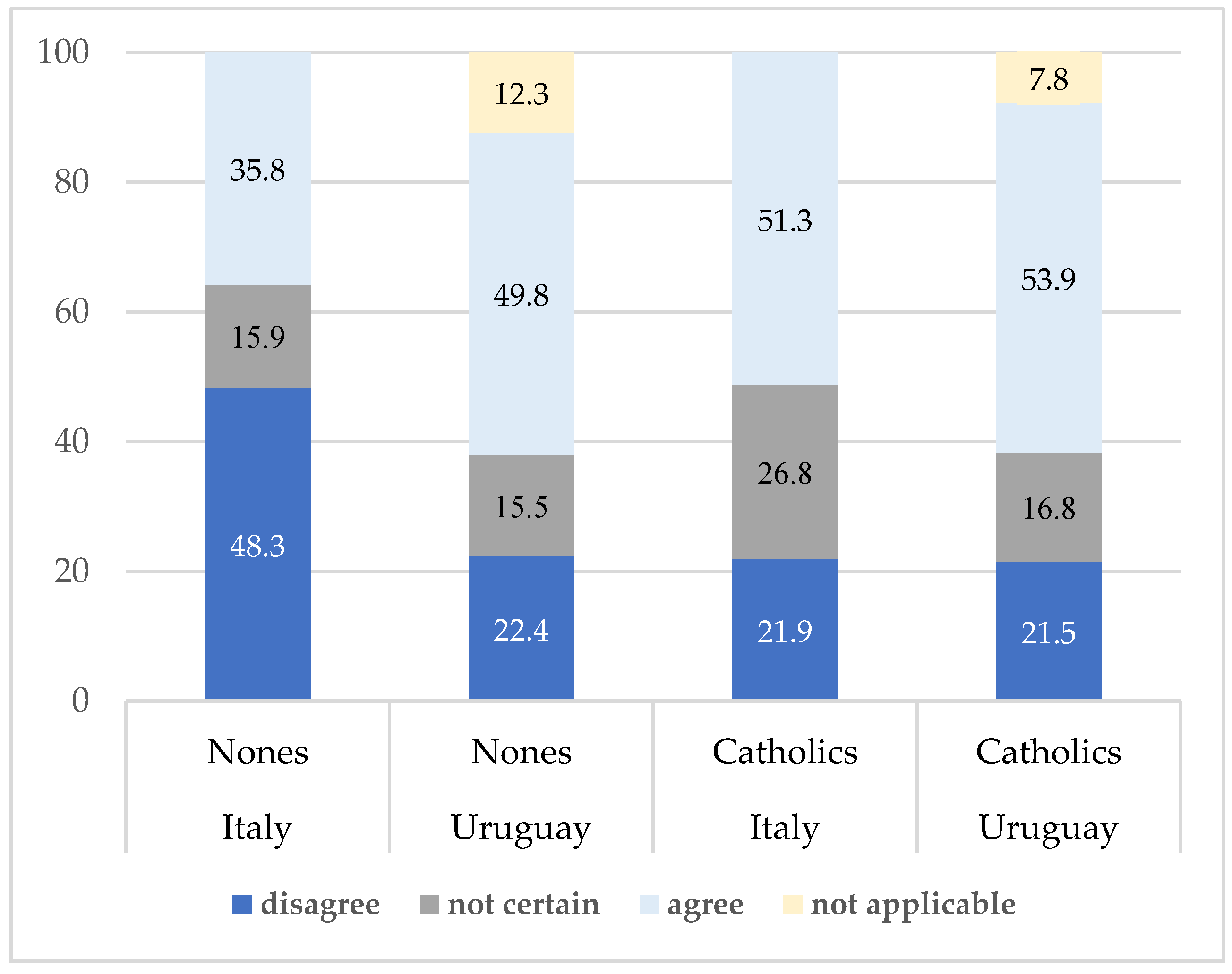

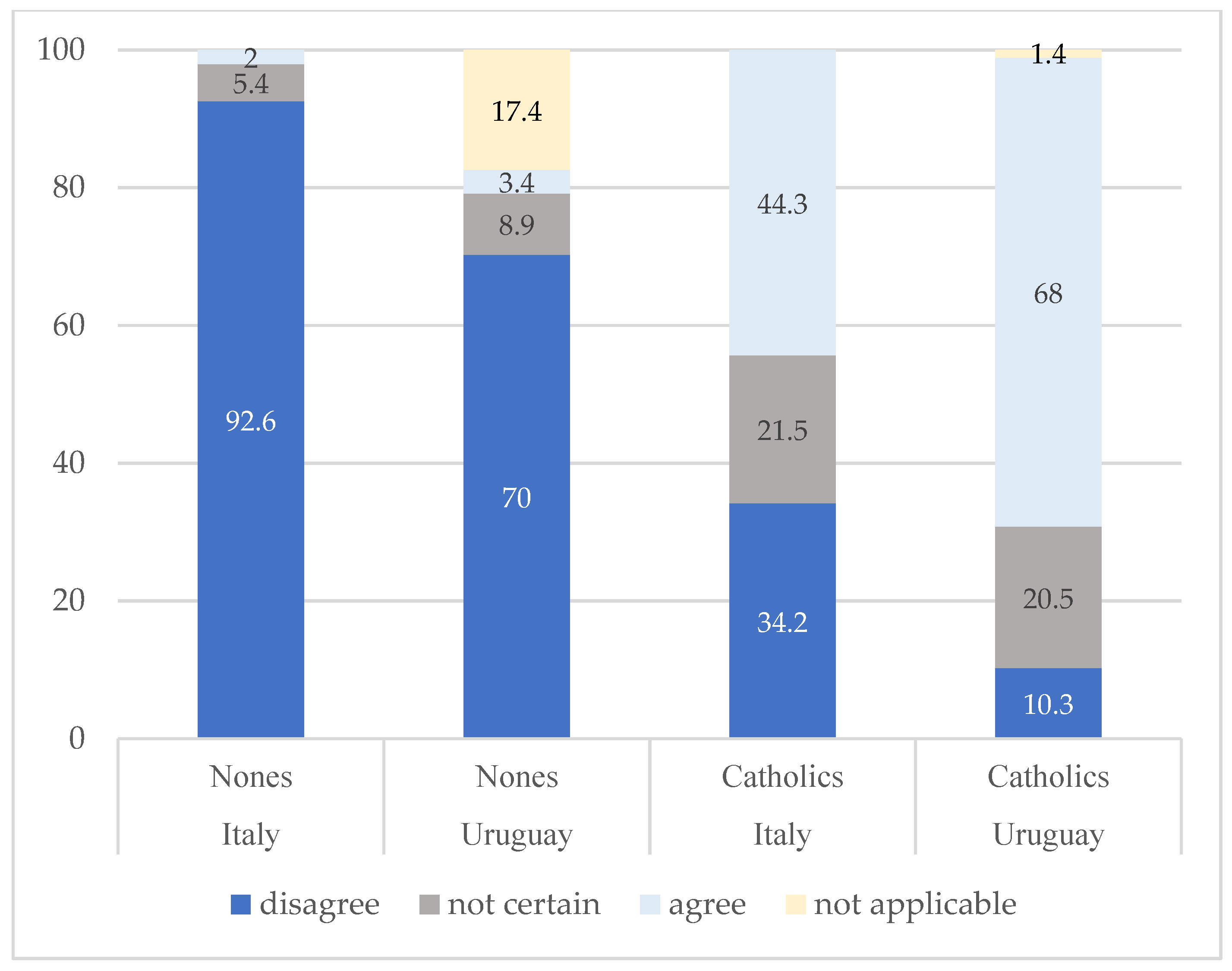

4.2. Religious Belief, Practices, and Truth Claims among Nones

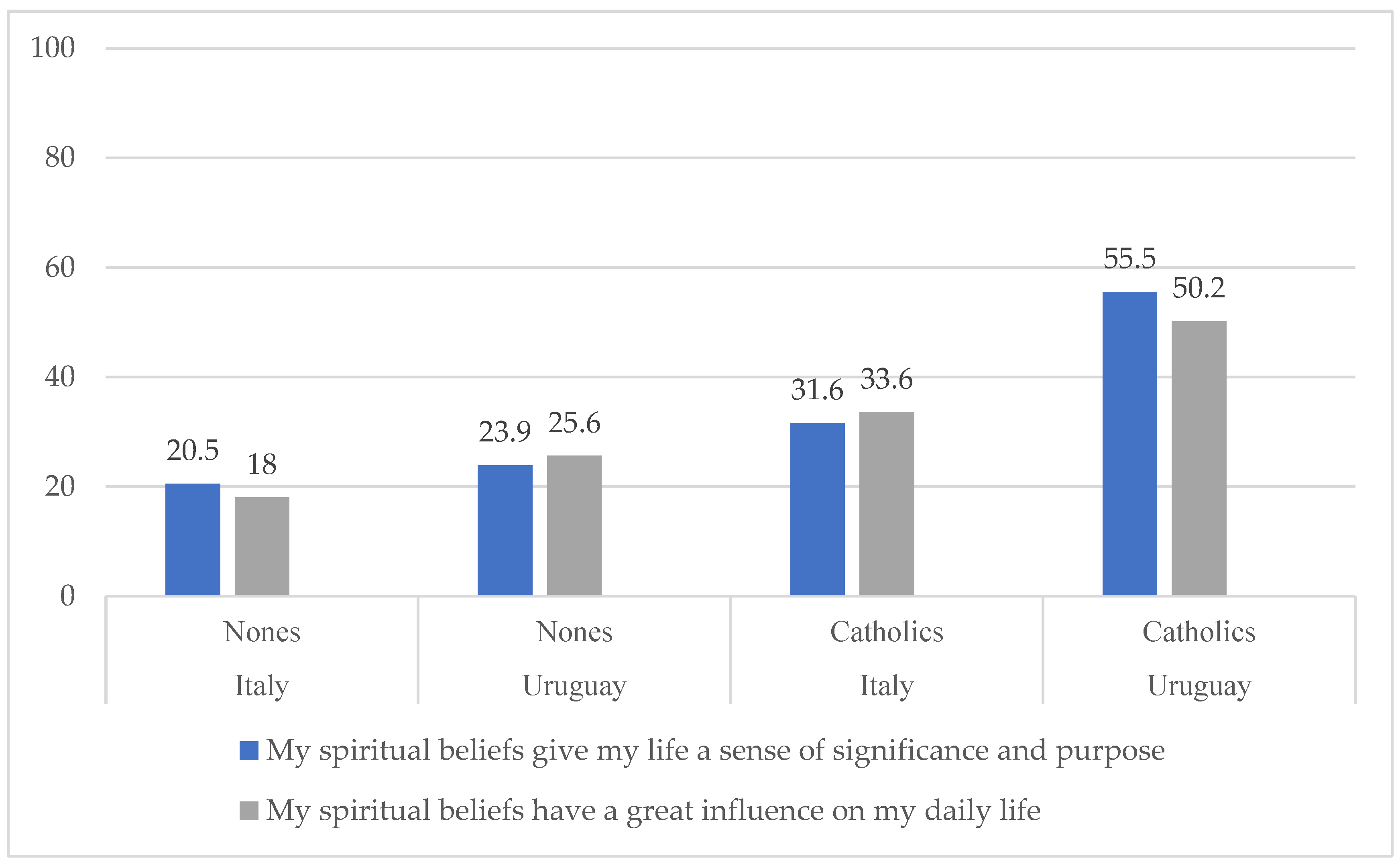

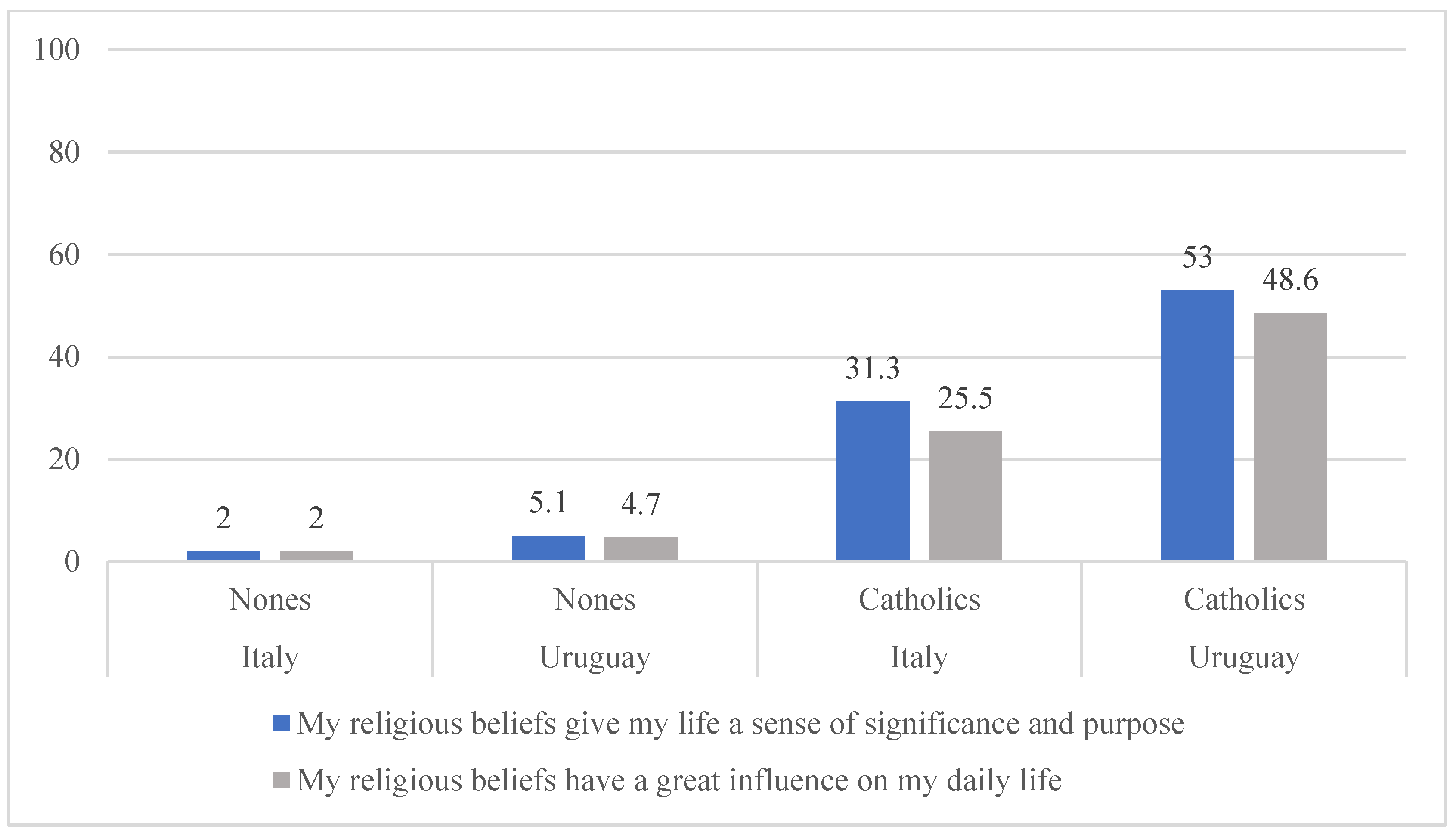

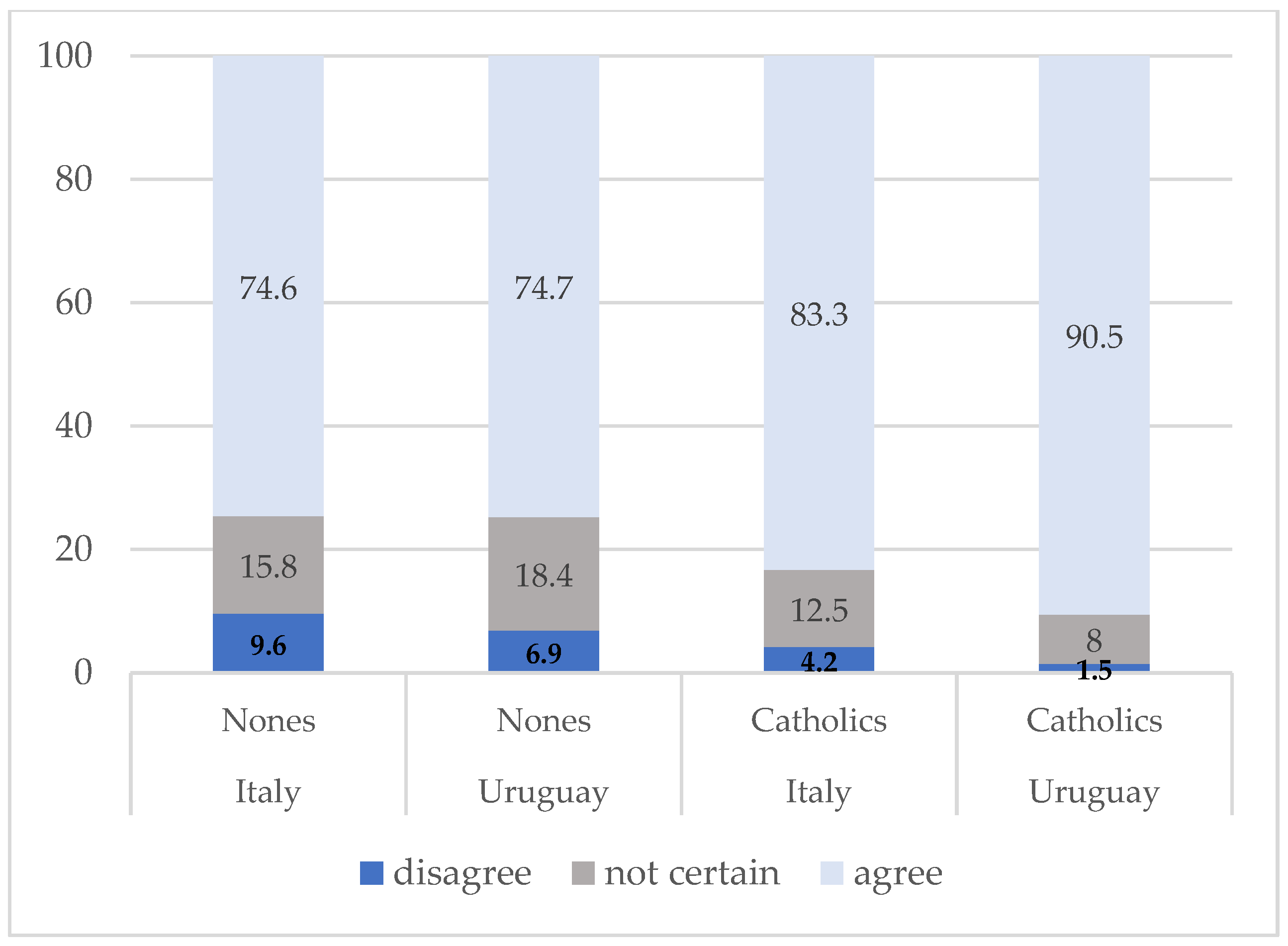

4.3. Spirituality–Religiosity Continuum and Individual Autonomy among Nones

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Given the nature and the size of this article, we do not focus on a broader sociological debate about spirituality revolution. See the following for details: (Flanagan and Jupp 2007; Heelas 2008; Heelas and Woodhead 2005; Giordan 2016; McGuire 2008; Ammerman 2013). |

| 2 | These profiles diverge in their perspectives on the quest for life’s meaning: deemed unimportant for “traditionalists” while significant for “Church spirituality” (Giordan 2010). Interestingly, those who considered the quest for life’s meaning important were divided into mostly similar groups: for those to whom reference to the Church for spiritual growth was not important (with types of “private spirituality” and “personal quest”) and for whom it was important (with types of “Church spirituality” and “critical people”). |

| 3 | This percentage contains the sum of people who responded “Believer, does not belong to the Church”; “Agnostic”; “Atheist”; and “None”. |

| 4 | The full list included the following options: No religion, Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox Christian, Pentecostal, Other Christian tradition, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Sikh, and Other (specify). |

| 5 | The introduction of the “non-applicable” option in the questionnaire on the Social Perception of Religious Freedom, especially concerning the statement about belief in God, came from its testing on the Italian sample in 2018. The original version of the instrument did not contain this option. The aim was to explore whether individuals identifying as Nones would choose this category instead of selecting the “disagree” option. In the questionnaire administered in Uruguay, this option was extended to questions concerning belief and spiritual and religious identities. |

References

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2003. Religious identities and religious institutions. In Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Michelle Dillon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 207–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Sacred Stories, Spiritual Tribes: Finding Religion in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Astley, Jeff, and Leslie J. Francis. 2016. Introducing the Astley–Francis Theology of Religions Index: Construct validity among 13- to 15-year-old students. Journal of Beliefs & Values 37: 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza Correa, Jorge, and Patricia Imbarack Dagach. 2023. Jóvenes “sin religión” en Chile: Un acercamiento cualitativo. Ultima década 31: 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagg, Samuel, and David Voas. 2010. The triumph of indifference: Irreligion in British society. In Atheism and Secularity: Voume 2—Global Expressions. Edited by Phil Zuckerman. Santa Barbara: Praeger, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Joseph O., and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2016. Gendering (non) religion: Politics, education, and gender gaps in secularity in the United States. Social Forces 94: 1623–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Joseph O., and Buster G. Smith. 2015. American Secularism: Cultural Contours of Nonreligious Belief Systems. New York: NYU Press, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, Lori G., and Steven Tomlins. 2015. Atheist Identities—Spaces and Social Contexts. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, William M., and Lorena Peña Rodríguez. 2023. Creencias y prácticas de jóvenes creyentes no afiliados en Bogotá. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 85: 1015–43. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, William M., Cely Julián E, and Sonia Larotta. 2022. El cambio religioso en Colombia en el siglo XXI: Hipótesis de trabajo. In Recomposición del campo religioso colombiano en el siglo XXI. Impactos y desafíos para la construcción de paz, la equidad de género y la inclusión social. Edited by Julián Ernesto Cely. Bogotá: Act Iglesia Sueca/World Vision/Comisión Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz, pp. 20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Berzano, Luigi. 2019. The Fourth Secularization. Autonomy of Individual Lifestyles. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berzano, Luigi. 2023. Senza più la domenica. Viaggio nella spiritualità secolare. Torino: Effatà. [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, Anthony J., Olga Breskaya, and Giuseppe Giordan. 2020. Religious freedom between religion and spirituality. Religioni e Società XXXV: 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Breskaya, Olga, and Giuseppe Giordan. 2019. Measuring the social perception of religious freedom: A sociological perspective. Religions 10: 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breskaya, Olga, and Giuseppe Giordan. 2021. One, Many or None. Religious Truth-Claims and Social Perception of Religious Freedom. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 12. Religious Freedom: Social-Scientific Approaches. Edited by Olga Breskaya, Roger Finke and Giuseppe Giordan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 51–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2015. Believing to Belong: Negotiation and Expression of American Identity at a Non-religious Camp. Ph.D. dissertation, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2022. Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, Ryan P. 2020. How many “nones” are there? Explaining the discrepancies in survey estimates. Review of Religious Research 62: 173–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, Ryan P. 2021. The Nones. Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, Gerardo. 2006. Laicismo y Política en el Uruguay Contemporáneo. Una mirada desde la Historia. In Laicidad en América Latina y Europa. Repensando lo religioso entre lo público y lo privado en el siglo XXI. Edited by Néstor Da Costa. Montevideo: Productora Editorial, CLAEH, pp. 121–59. [Google Scholar]

- Camurça, Marcelo A. 2017. Os “sem religião” no Brasil: Juventude, periferia, indiferentismo religioso e trânsito entre religiões institucionalizadas. Estudos de religião 31: 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, José. 2011. The Secular, Secularizations, Secularism. In Rethinking Secularism. Edited by Ryan Cragun, Mark Juergensmeyer and Jonathan VanAntwerpen. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, Roberto. 2017. Diffused Religion: Beyond Secularization. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, Katie, Cristopher P. Scheitle, and Ellory Dabbs. 2021. Multiple (non) religious identities leads to undercounting religious nones and Asian religious identities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60: 424–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragun, Ryan T., and Joseph H. Hammer. 2011. One person’s apostate is another person’s convert: What terminology tells us about pro-religious hegemony in the sociology of religion. Humanity & Society 35: 149–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cragun, Ryan T., and Kevin McCaffree. 2021. Nothing is not something: On replacing nonreligion with identities. Secular Studies 3: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, Néstor. 2006. La laicidad uruguaya, de la formulación de principios del siglo XX a las realidades del siglo XXI. In Laicidad en América Latina y Europa. Repensando lo religioso entre lo público y lo privado en el siglo XXI. Edited by Néstor Da Costa. Montevideo: Productora Editorial, CLAEH, pp. 161–77. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, Néstor. 2017. Creencia e increencia desde las vivencias cotidianas. Una mirada desde Uruguay. Estudos de religiao 31: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, Néstor. 2019. Creyentes sin religión y ateos en el laico Uruguay. In La religión como experiencia cotidiana: Creencias, prácticas y narrativas espirituales en Sudamérica. Edited by Hugo H. Rabbia, Gustavo S. J. Morello and Nestor Da Costa y Catalina Romero. Editorial de la Universidad Católica de Córdoba. pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, Néstor, Gustavo Morello, Hugo H. Rabbia, and Catalina Romero. 2021. Exploring the nonaffiliated in South America. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 89: 562–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, Néstor, Valentina Pereira Arena, and Camila Brusoni. 2019. Individuos e instituciones: Una mirada desde la religiosidad vivida. Sociedad y religión 29: 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, Kees. 2018. The Liquidation of the Church. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Diotallevi, Luca. 1999. Religione, Chiesa e modernizzazione. Il caso italiano. Roma: Borla. [Google Scholar]

- Diotallevi, Luca. 2001. Il rompicapo della secolarizzazione italiana: Caso italiano, teorie americane e revisione del paradigma della secolarizzazione. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino. [Google Scholar]

- Diotallevi, Luca. 2022. Il compito di una—Eventuale—“quarta sociologia della religione italiana”. Prima parte. Sociologia 3: 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, Elizabeth. 2016. Choosing Our Religion: The Spiritual Lives of America’s Nones. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, Juan C., María E. Funes, and María Sol Prieto. 2020. Ateos, agnósticos y creyentes sin religión: Análisis cuantitativo de los sin filiación religiosa en la Argentina. Sociedad y Religión 30: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Kieran, and Peter C. Jupp. 2007. A Sociology of Spirituality. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Furstova, Jana, Klara Malinakova, Dagmar Sigmundova, and Peter Tavel. 2021. Czech Out the Atheists: A Representative Study of Religiosity in the Czech Republic. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 31: 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garelli, Franco. 2016. Piccoli atei crescono. Davvero una generazione senza Dio? Mulino: Bologna. [Google Scholar]

- Garelli, Franco. 2020. Gente di poca fede. Il sentimento religioso nell’Italia incerta di Dio. Mulino: Bologna. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe. 2007. Spirituality: From a Religious Concept to a Sociological Theory. In A Sociology of Spirituality. Edited by Kieran Flanagan and Peter C. Jupp. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 161–81. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe. 2010. Believers in progress. Youth and religion in Italy. In Youth and Religion. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 10. Edited by Giuseppe Giordan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 353–81. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe. 2014. Introduction: Pluralism as legitimization of diversity. In Religious Pluralism. Framing Religious Diversity in the Contemporary World. Edited by Giuseppe Giordan and Enzo Pace. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe. 2016. Spirituality. In Handbook of Religion and Society. Edited by David Yamane. Cham: Springer, pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Greising Díaz, Carolina. 2023. Algunas reflexiones a propósito de la “teoría del gueto católico” en el Uruguay laico. Humanidades 14: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heelas, Paul. 2008. Spiritualities of Life: New Age Romanticism and Consumptive Capitalism. Malden-Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution. Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yinxuan. 2020. How Christian upbringing divides the religious nones in Britain: Exploring the imprints of Christian upbringing in the 2016 EU referéndum. Journal of Contemporary Religion 35: 341–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald F. 2021. Religion’s Sudden Decline: What’s Causing It, and What Comes Next? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin, Barry A., Ariela Keysar, Ryan T. Cragun, and Juhem Navarro-Rivera. 2009. American Nones: The Profile of the No Religion Population. Hartford: Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Latinobarómetro Survey. 2023. Available online: https://www.latinobarometro.org/latContents.jsp (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Lee, Lois. 2012. Research note: Talking about a revolution: Terminology for the new field of non-religion studies. Journal of Contemporary Religion 27: 129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Lois. 2015. Recognizing the Non-Religious: Reimagining the Secular. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Lois. 2017. Religion, difference and indifference. In Religious Indifference. Edited by Johannes Quack and Cora Schuh. Basel: Springer, pp. 101–21. [Google Scholar]

- Madge, Nicola, and Peter J. Hemming. 2017. Young British religious ‘nones’: Findings from the youth on religion study. Journal of Youth Studies 20: 872–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallimaci, Fortunato, Esquivel Juan, and Gabriela Irrázabal. 1999. De la homogeneidad a la diversidad: Las actuales transformaciones en el campo religioso en la sociedad argentina. Revista Sociedade e Estado 14: 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marzal, Manuel. 2000. De los viejos ateísmos a los agnosticismos posmodernos. Anthropologica, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, Gustavo S. J. 2021. Lived Religion in Latin America: An Enchanted Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Enzo. 2013. Le religioni nell’Italia che cambia. Mappe e bussole. Roma: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Palmisano, Stefania, and Nicola Pannofino. 2017. So far and yet so close: Emergent spirituality and the cultural influence of traditional religion among Italian youth. Social Compass 64: 130–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, Stefania, and Nicola Pannofino. 2021. Religione sotto spirito. Viaggio nelle nuove spiritualità. Milano: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Cristián. 1993. Otra lógica en América Latina. Religión popular y modernización capitalista. Santiago de Chile: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Arena, Valentina. 2018. “En busca de los católicos distanciados: Entre los católicos alejados y los creyentes sin iglesia”. In Newsletter N°37 ACSRM. Edited by Asociación de Cientistas Sociales de la Religión del Mercosur. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Arena, Valentina, and Camila Brusoni. 2017. Individuos, instituciones y espacios de fe. El caso de los católicos en Uruguay. Visioni Latinoamericane 17: 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Arena, Valentina, and Gustavo S. J. Morello. 2022. Entre el opio del pueblo y la búsqueda de la salvación. Aproximaciones a la religiosidad vivida desde América Latina. Revista De Estudios Sociales, Revista de Estudios Sociales 82: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quack, Johannes, and Cora Schuh. 2017. Conceptualising Religious Indifferences in Relation to Religion and Nonreligion. In Religious Indifference. Edited by Quack Johannes and Cora Schuh. Basel: Springer, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbia, Hugo H. 2017. Explorando los sin religión de pertenencia en Córdoba, Argentina. Universidade Metodista de São Paulo; Estudos de Religiao 31: 131–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodé, Patricio. 2007. Construcción de ciudadanía y fe cristiana. Una selección de sus textos. Edited by Gerardo Caetano y Néstor Da Costa. Montevideo: Editorial Doble Clic Editoras. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazín, Jean P. 2017. ¿Guiados por Dios o por Sí Mismos? Estudio comparativo entre adeptos a las espiritualidades alternativas y adeptos a las iglesias evangélicas. Cuestiones Teológicas 44: 373–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senra, Flavio, Izabella Faria, and José Campos. 2020. Os sem-religião. Espacialização e vozes de uma transformação. Caderno de Geografia 30: 480–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren E. 2014. Changing Faith: The Dynamics and Consequences of Americans’ Shifting Religious Identities. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gregory A., Patricia Tevington, Justin Nortey, Michael Rotolo, Asta Kallo, and Becka A. Alper. 2024. Religious ‘Nones’ in America: Who They Are and What They Believe, Pew Research Center. United States of America. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/11315293/religious-nones-in-america/12200947 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Smith, Jesse M., and Ryan T. Cragun. 2019. Mapping religion’s other: A review of the study of nonreligion and secularity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 319–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, Joel, and Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme. 2020. None of the Above: Nonreligious Identity in the US and Canada. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins, Steven, and Lori G. Beaman. 2015. Introduction. In Atheist Identities—Spaces and Social Contexts. Edited by Lori G. Beaman and Steven Tomlins. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Voas, David. 2009. The rise and fall of fuzzy fidelity in Europe. European Sociological Review 25: 155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voas, David, and Siobhan McAndrew. 2012. Three puzzles of non-religion in Britain. Journal of Contemporary Religion 27: 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Italy | Uruguay | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 20.8 | 21.7 |

| Female | 77.8 | 59.9 |

| Citizen | 92.9 | 95.5 |

| From urban area | 31.9 | 77.2 |

| From suburban area | 38.4 | 19.2 |

| From rural area | 29.7 | 3.6 |

| No religion | 29.9 | 53.7 |

| Catholic | 63.8 | 39.3 |

| Mother’s citizenship | 85 | 94.1 |

| Father’s citizenship | 86.8 | 94.7 |

| Italy | Uruguay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fr. | % | Fr. | % | |

| No religion (Nones) | 304 | 29.9 | 540 | 53.7 |

| Roman Catholic | 648 | 63.8 | 395 | 39.3 |

| Protestant | 2 | 0.2 | 27 | 2.7 |

| Christian—Orthodox | 17 | 1.7 | 1 | 0,1 |

| Pentecostal | 4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other Christian tradition | 4 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Muslim | 24 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Jewish | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 1.9 |

| Buddhist | 4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hindu | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sikh | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 6 | 0.5 | 15 | 1.4 |

| Total | 1016 | 100.0 | 1006 | 100.0 |

| Italy | Uruguay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Nones | 42.2% | 26.7% | 60.6% | 50.4% |

| Catholics | 53.8% | 67.1% | 35.7% | 42.7% |

| Religious minorities | 4.0% | 6.2% | 3.8% | 6.9% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Mother with a University Degree | Father with A University Degree | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Uruguay | Italy | Uruguay | |

| Nones | 23.4% | 68.4% | 20.7% | 56.5% |

| Catholics | 15.6% | 65.7% | 15.4% | 58.3% |

| Religious minorities | 24.6% | 66.1% | 23.2% | 57.1% |

| Italy | Uruguay | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nones | Catholics | Religious Minorities | Nones | Catholics | Religious Minorities | |

| It is important to me to live in a democratically governed country | 4.38 | 4.31 | 4.24 | 4.48 | 4.56 | 4.70 |

| Freedom to criticize religious leaders is an important aspect of religious freedom | 3.79 | 3.30 | 3.11 | 3.95 | 3.60 | 3.93 |

| Having many different religious points of view is good for Italian/Uruguayan society | 4.18 | 3.96 | 4.21 | 4.30 | 4.43 | 4.38 |

| Nones | Catholics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Uruguay | Italy | Uruguay | |

| Strongly disagree | 62.1% | 27.1% | 6.3% | 1.3% |

| Disagree | 16.9% | 14.4% | 8.0% | 1.0% |

| Not certain | 15.3% | 20.5% | 24.3% | 8.3% |

| Agree | 4.7% | 10.8% | 38.0% | 39.3% |

| Strongly agree | 1.0% | 5.1% | 23.5% | 49.2% |

| Not applicable | 22.0% | 8% | ||

| Italy (Nones) | Uruguay (Nones) | Italy (Catholics) | Uruguay (Catholics) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you pray in your home or by yourself? | ||||

| Never | 91.7 | 85.1 | 33.6 | 22.8 |

| Occasionally | 5.6 | 13.8 | 39.4 | 37.8 |

| At least once a month | 1.3 | 0.4 | 3.1 | 9.1 |

| At least once a week | 0.7 | 0.2 | 9.3 | 13.2 |

| Nearly every day | 0.7 | 0.6 | 14.7 | 17 |

| Apart from special occasions (like weddings), how often do you attend a religious worship service (e.g., in a church, mosque, or synagogue)? | ||||

| Never | 82.6 | 77.1 | 28.2 | 22.4 |

| Occasionally | 10.5 | 16.7 | 26.2 | 26 |

| A few times a year | 6.6 | 5.8 | 22.2 | 26 |

| At least once a month | 0.3 | 0.20 | 6.3 | 8.4 |

| Nearly weekly or more | 0 | 0.20 | 17 | 17.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Breskaya, O.; Pereira Arena, V. Religious Nones and Spirituality: A Comparison between Italian and Uruguayan Youth. Religions 2024, 15, 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070769

Breskaya O, Pereira Arena V. Religious Nones and Spirituality: A Comparison between Italian and Uruguayan Youth. Religions. 2024; 15(7):769. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070769

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreskaya, Olga, and Valentina Pereira Arena. 2024. "Religious Nones and Spirituality: A Comparison between Italian and Uruguayan Youth" Religions 15, no. 7: 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070769

APA StyleBreskaya, O., & Pereira Arena, V. (2024). Religious Nones and Spirituality: A Comparison between Italian and Uruguayan Youth. Religions, 15(7), 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070769