Kucha and Termez—Caves for Mindful Pacing and Seated Meditation

Abstract

1. Introduction

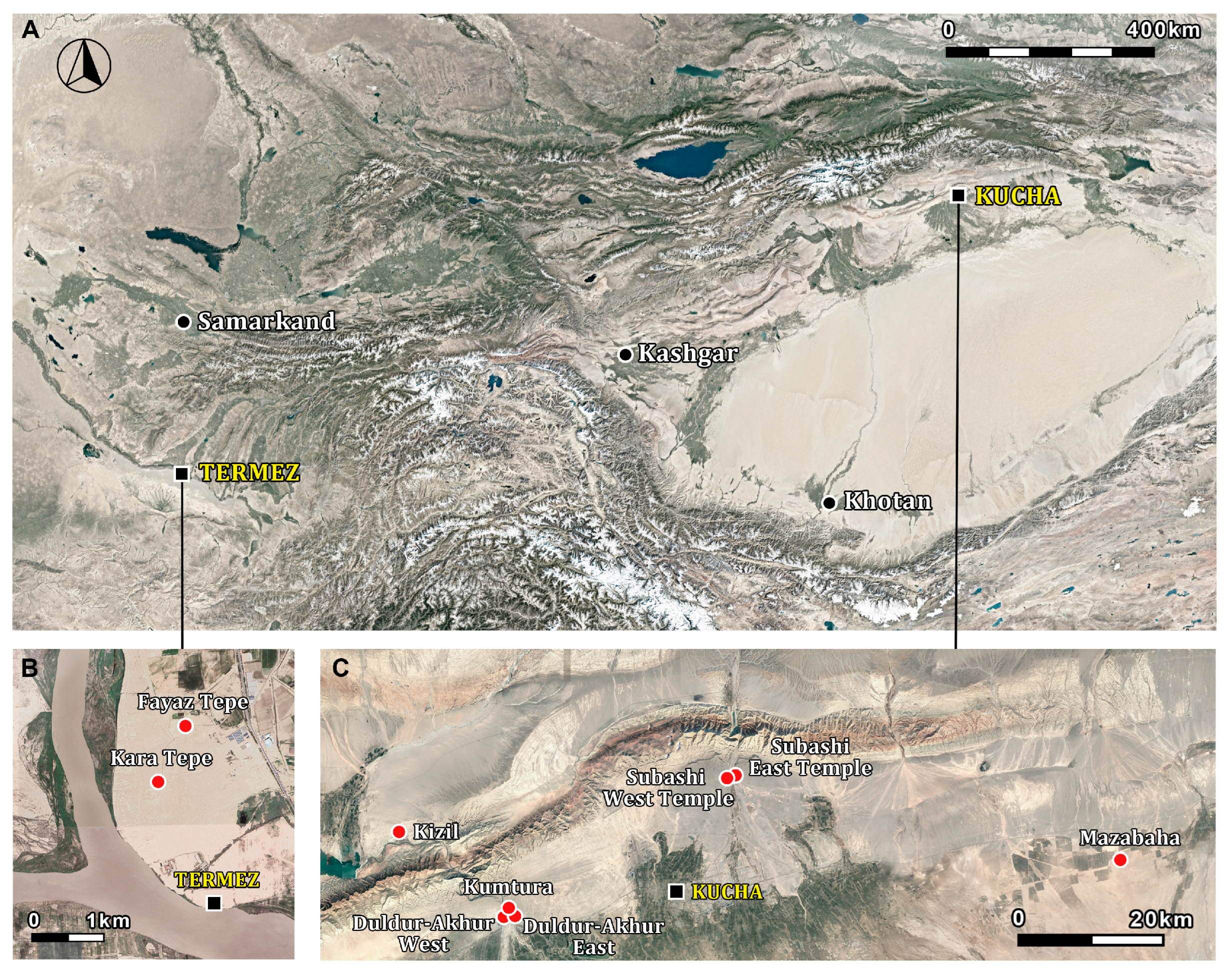

2. The Monasteries of Termez and Meditation

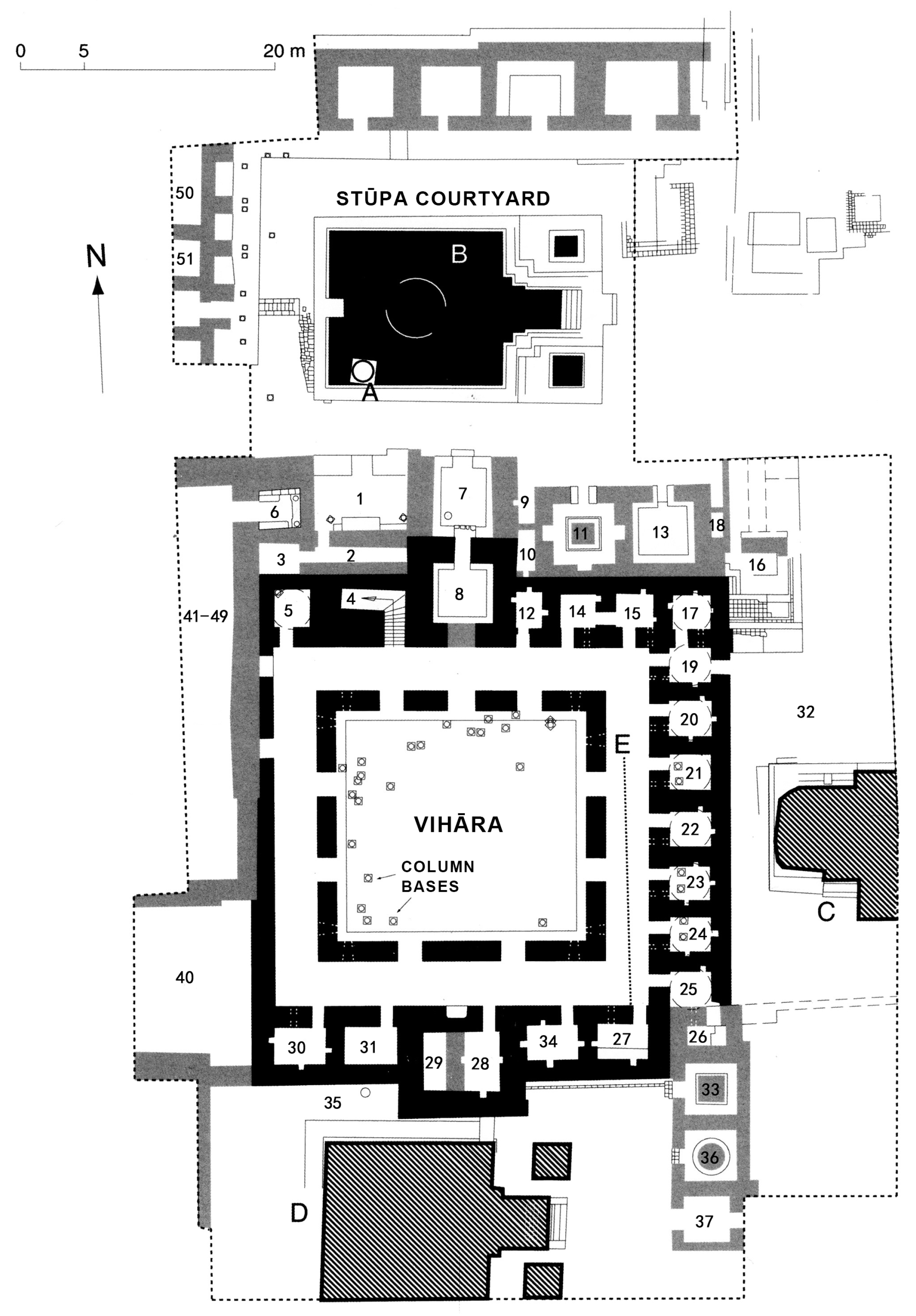

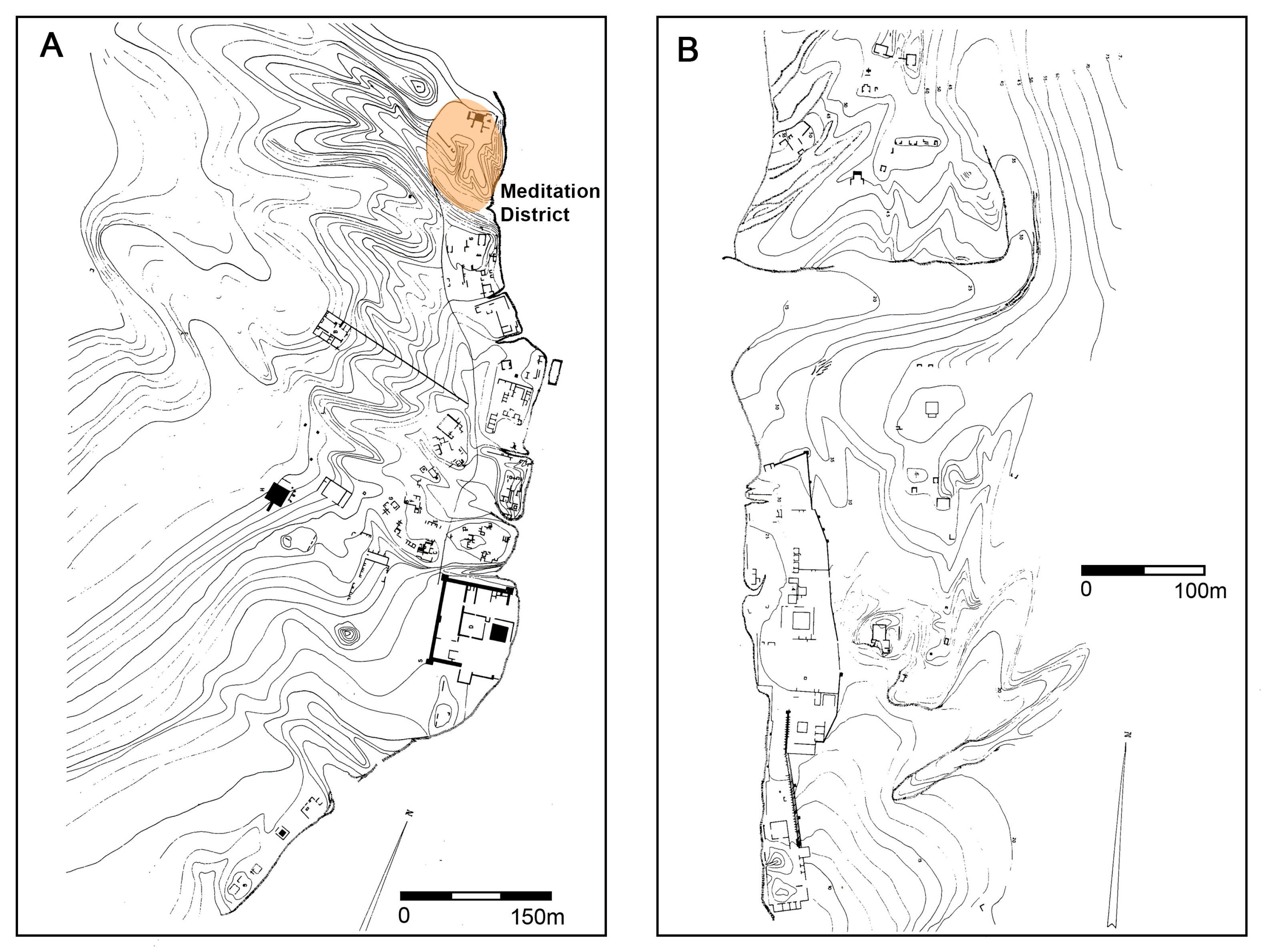

2.1. Kara Tepe

2.2. On the Function of the South and West Districts

3. Kucha Monasteries and Meditation

3.1. Meditation Cells

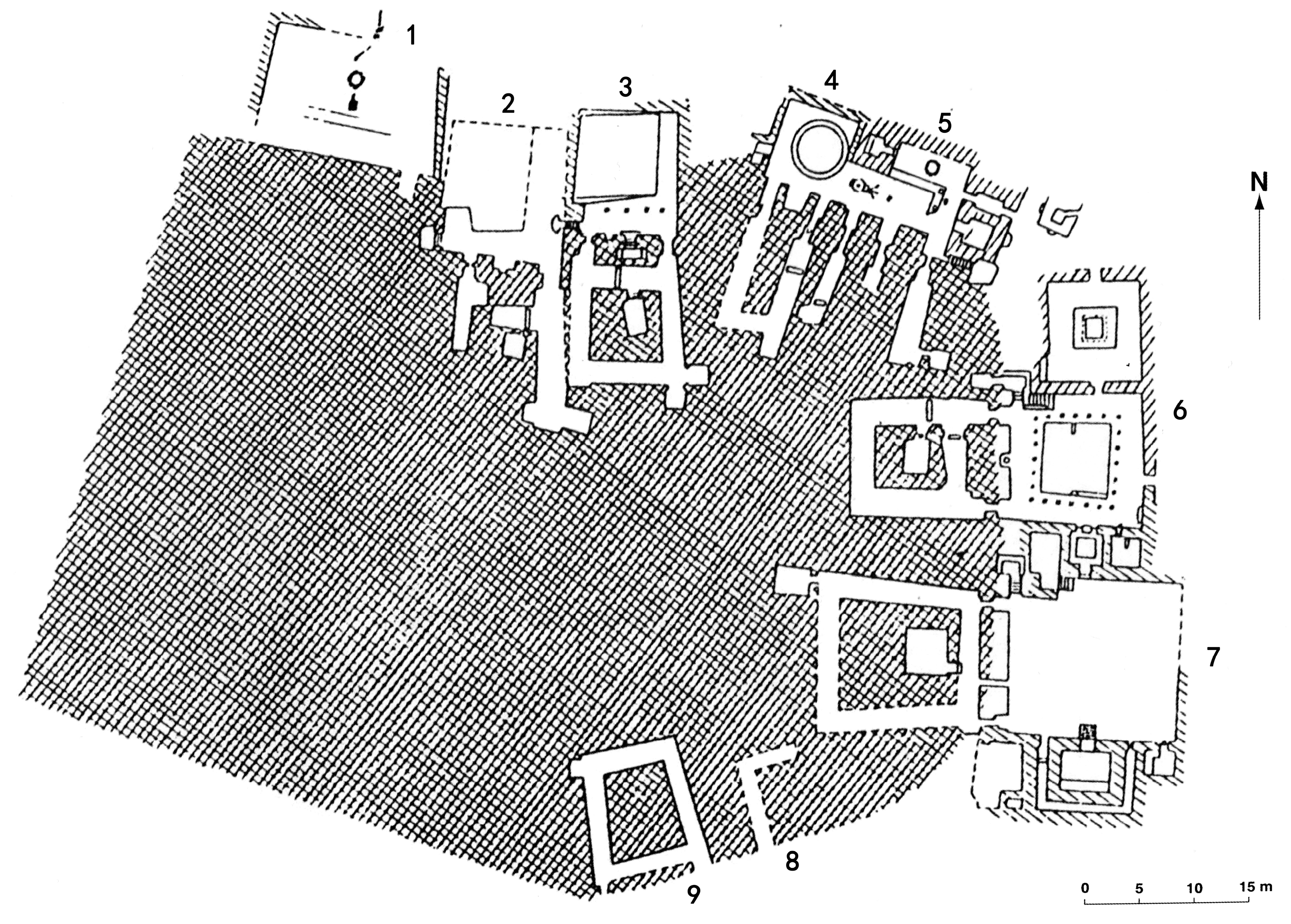

3.2. Mazabaha

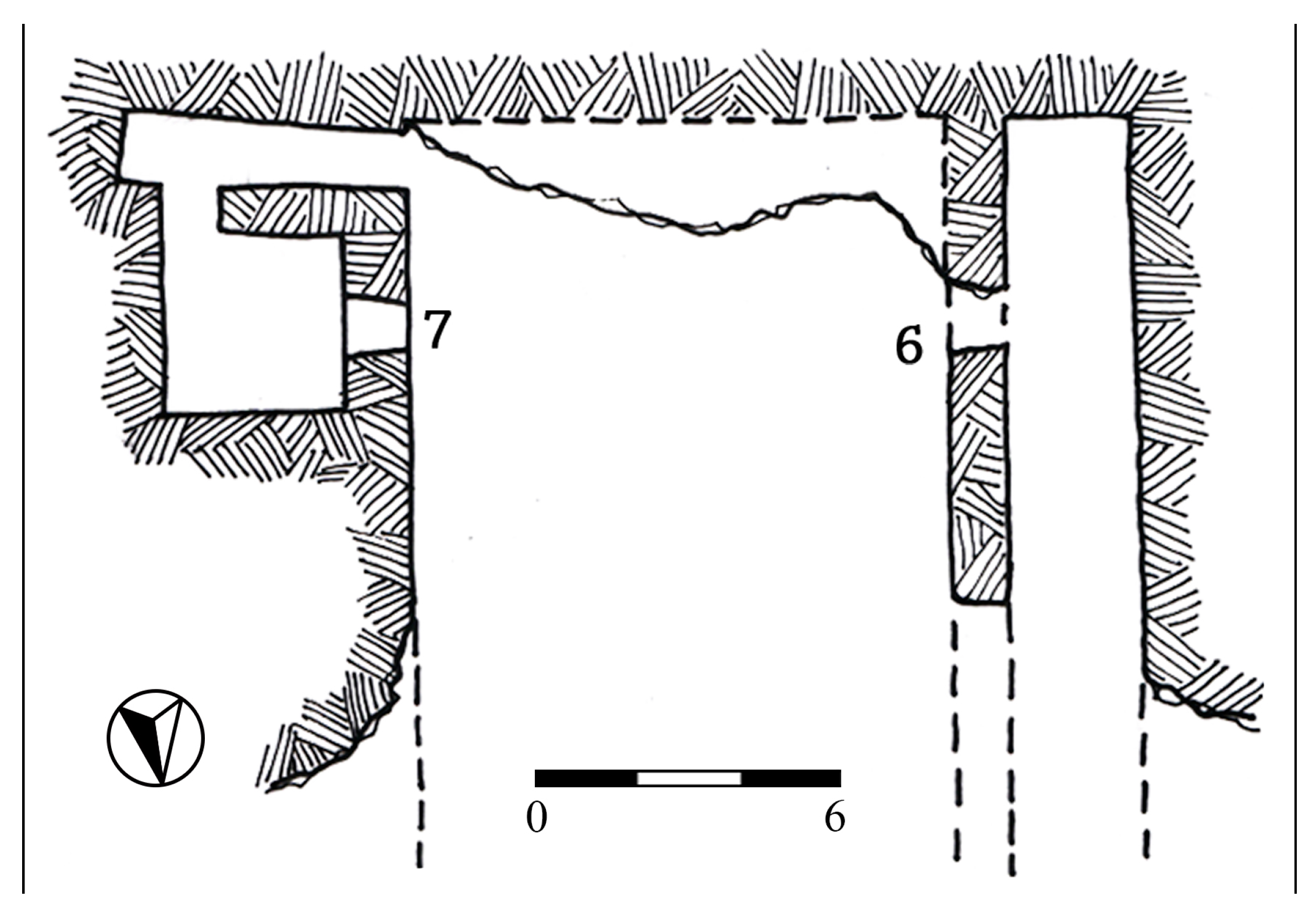

3.3. Duldur-Akhur

3.4. Subashi

4. About Mindful Pacing (caṅkrama) in Buddhism

4.1. Two Combined Meditative Practices in Buddhism

From this observation, it becomes evident that mindful pacing and sitting meditation emerge as two pivotal practices for monks within the Buddhist tradition.… (A Bhikṣu) goes to a secluded place, whether under a tree, or in an empty hut, and can practice mindful pacing, or sitting meditation to purify all hindrances in his mind.Having purified all hindrances in his mind during the day, whether practicing mindful pacing or sitting meditation, in the first part of the night, he again, whether practicing mindful pacing or sitting meditation, purifies all hindrances in his mind.Having purified all hindrances in his mind in the first part of the night, whether practicing mindful pacing or sitting meditation, in the middle part of the night, he enters the dwelling intending to lie down, folds his uttarāsaṅga fourfold and lays it on his bed, folds up his saṃghātī to make a pillow, and lies down on his right side, with his feet overlapping…In the last part of the night, he rises from his bed, whether for practicing mindful pacing or sitting meditation, he purifies all hindrances in his mind. This is the lion-like rule concerning the sleeping27 of bhikṣus.……至無事處,或至樹下,或空室中,或經行,或坐禪,淨除心中諸障礙法。晝或經行或坐禪,淨除心中諸障礙已。復於初夜或經行,或坐禪,淨除心中諸障礙法。於初夜時,或經行,或坐禪,淨除心中諸障礙已。於中夜時,入室欲臥,四疊優哆邏僧敷著床上,襞僧伽梨作枕,右脅而臥,足足相累…… 彼後夜時速從臥起,或經行,或坐禪,淨除心中諸障礙法,如是比丘師子臥法。(T 26 [I], pp. 473c20–474a4)

4.2. Location and Design of Mindful Pacing Paths

In the state of Ālavi, a new monastery was built. The monks had no place for walking meditation, so they reported this matter to the Buddha. The Buddha said, ‘A place for walking meditation should be made’. Because the region was hot and monks would sweat while walking, the Buddha further advised, ‘Trees should be planted in the walking meditation area.佛在阿羅毘國,新作僧伽藍,諸比丘無經行處,是事白佛,佛言:“應作經行處。”彼土熱,經行時汗流,佛言:“應經行處種樹。”(T.1435 [XXIII], p. 284a1–4)

At that time, the king constructed paths for mindful pacing within a forest and stayed there. The segments and paths of that forest were connected; hence it was named the ‘Segments Forest’.時王即為於一林中造經行處,即於中住,以彼支節分分相連,即名此林為分分林。(T1451 [XXIV], p. 331a1–2)

4.3. Records of Mindful Pacing by Buddhists Monks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| 1 | Xuanzang states that the perimeter of the city walls of Termez was about 20 li (one li 里 corresponds to ca. 450 m). In Termez, there were a dozen Buddhist monasteries and about a thousand monks, but it is not specified to which doctrinal current they belonged (Beal 1906, p. I, 39; Ji et al. 1985, p. 103). Based on epigraphic data, it seems as if the dominant Buddhist school present in Termez was the Mahāsāṃghika (Staviskii and Mkrtychev 1996, p. 222; Fussman 2011a, p. 35). Fussman believes that the monasteries of Kara Tepe and the nearby Fayaz Tepe did not change affiliation during the six centuries of their history. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | The structures of the monastery belong to several construction phases; I refer here to the late phase, which is better excavated and has structures that could be discerned; the structures below, which belong to earlier phases, do not reveal a clear plan. |

| 4 | To make it easier to identify individual complexes in the South District, we replaced the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet with Arabic numerals, see Figure 6. |

| 5 | The archaeological reports are vague about the phases of excavation of the corridors and the dating of the features within them. There are no data available concerning the unfinished corridors, and whether they were utilized. The date of the opening of niches within the corridors or in the rear wall of the courtyards remains unclear. Some of the caves were reutilized as tombs in a late period, but it remains unclear how much this repurposing impacted the structure of the caves. For a succinct overview of these issues see Fussman (2011a, pp. 15–18). |

| 6 | In the search for the origins of central pillar caves, the caves in Kara Tepe and other Central Asian caves were considered as possible prototypes, cf. Qinlan Zhao (1995, pp. 34–35). On the contrary, Rhie (1999–2002, pp. 189–90, 644) sees only a possible influence rather than a direct derivation. The central pillar caves of Central China (zhongxin zhu ku 中心柱窟), also called pagoda temple caves (ta miao ku 塔廟窟), are characterized by an unexcavated ‘pillar’ in the center of the main hall. On this issue see Vignato and Casalini (2022). In the central pillar caves in Kucha, the cave is fully decorated, the main Buddha image inserted in the niche carved on the side of the pillar facing the entrance. Modelled or painted episodes from the Buddha’s life, images of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, celestial beings and decorative motifs cover all walls, ceiling, and even the floor. The iconographic program invites the worshipper to perform circumambulation of the pillar in a clockwise direction. If we examine the Kara Tepe caves, on the other hand, we notice that they do not have a main hall, but only narrow corridors of the same width, lack a worship image across the entrance, and are almost completely devoid of decoration; they are accessed directly by very deep side corridors, which do not arouse the idea of being designed for circumambulation of a pillar. A comparison of the two types highlights how they were designed for completely different functions. |

| 7 | In the corridors of Complex 6 is preserved a painting depicting the Buddha accompanied by monks, probably in the scene of the First Sermon (Lo Muzio 2017, pp. 194–95, Table 7.4). |

| 8 | Note that, in Kucha, a place of worship is usually found near or above meditation caves, which could be either a decorated cave or a stūpa (see below). One wonders whether the stairway in Complex 1 was meant to lead to a place of worship such as a small stūpa, functionally similar to those in the courtyards of Facilities 4 and 6. |

| 9 | In some complexes in the South District of Kara Tepe, a niche opens at the center of the rear wall of the court, located between the two entrances (Complexes 2, 3, 4, and 6). Although the time in which these niches were excavated remains unclear, the presence of a statue or cult object would be in line with the practice of meditation. |

| 10 | The indication comes from Fussman (2011a, p. 21), who states that Fayaz Tepe monastery is located in a flat area 900 m north of Kara Tepe. |

| 11 | We base this on the chronology formulated by Fussman (2011a, pp. 18, 21, 25: Kara Tepe, 50–650 CE; Fayaz Tepe 50–400 CE). |

| 12 | Given the contemporaneity of the two monasteries and the different floor plans, one might wonder if one of them was used by nuns. Fussman (2011a, p. 33) points out that the inscriptions on the earthenware fragments only mention the names of monks, a fact that cannot be considered conclusive evidence. Moreover, he indicates that the term vihāra in Buddhist texts is used with the meaning of a male monastery, and he cites G. Schopen, who argues that nunneries were typically located within cities (Schopen 2008, pp. 229, 246–47). In Kucha, according to the 379 CE Preface concerning the history of the translation of the Bhikṣuṇīprātimokṣa (Biqiuni jieben suochu benxu 比丘尼戒本所出本序), preserved in the Collected Records concerning the Tripitaka (Chu sanzang jiji 出三藏記集), the larger convents housed 180 and 150 nuns, the smaller ones 30. The monks housed in the mentioned monasteries were fewer. It seems unlikely, however, that all these large structures were located within a relatively small town like Kucha. The issue of archaeological evidence of nunneries in Kucha has been recently discussed in Wang and Vignato (forthcoming). |

| 13 | Chinese Buddhist tradition reports that a conspicuous number of Kucha monks came to central China between the second and third centuries CE to translate religious texts into Chinese. For the bibliography on this topic, see Vignato and Hiyama (2022, p. 3, note 2). |

| 14 | According to Xuanzang’s, the perimeter of the city walls of Kucha was 17–18 li (Beal 1906, p. I, 19; Ji et al. 1985, p. 54). |

| 15 | Rock monasteries have been the subject of study for over a century. For bibliographical references, see Howard and Vignato (2015) and Vignato and Hiyama (2022). Monasteries on the surface have been investigated much less, see Zhang (2010). The most important study on Subashi and Duldur-Akhur remains the publication of Paul Pelliot’s materials (Hallade and Gaulier 1967–1982). Li Lin’s (2018) work and a recent study of Subashi sites (Sang 2021) are also useful. |

| 16 | Buddhism in Kucha went through several phases (Vignato and Hiyama 2022, pp. 7–9). Central pillar caves belong to a middle-late phase—possibly starting not earlier than the end of the 5th century CE. They usually form groups consisting of caves of different types or several central pillar caves. In several cases, small individual meditation caves seem to belong for the most part to the phase of the carving of central pillar caves (Vignato 2005, p. 133; Wei 2013). The later appearance of individual meditation cells in the rock monasteries of Kucha might explain the reason for the lack of this type in Termez. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | The plan of the monastery and all the information we have are based on Pelliot’s description (Hallade and Gaulier 1967–1982). A selection of artefacts, including some paintings, are preserved in the Guimet Museum. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | The area in front and on either side of Cave 9 has been excavated recently, revealing several rooms in its proximity, but the results have not yet been published. It is hoped that this excavation will definitively clarify the type of cave and its construction phases. |

| 21 | In the gorge immediately north of Duldur-Akhur West Monastery—First Valley—there are only a few decorated niches and only one central pillar cave, Cave 17. All belong to a late phase of the district’s history (Vignato and Hiyama 2022, p. 87). In the early phase there were only caves for meditation. |

| 22 | This district was briefly described in Howard and Vignato (2015, pp. 92–94). Wanli Ran’s (2020) recent publication presents the meditation caves as they currently are, not cleared of rubble, and with new numbering, which is unfortunately regrettably inconsistent. A map showing the location of the caves has not been published. Excavation of groups of monastic cells is ongoing in the East Monastery. |

| 23 | Some of the caves of this type in Subashi, such as Caves 1, 2, 4 in the West Monastery and Caves 1, 2 in the East Monastery, present decorations on the walls. These decorations are poorly studied; whether the paintings were part of the original plan or executed in a successive period remains to be determined. |

| 24 | Some of the caves are very damaged, and in some cases have been covered with plaster in recent decades—such as Cave 1. One must not be misled by the photographs. |

| 25 | Qinzhi Zhu (1992, pp. 239–40) suggests that, in the translation jingxing 經行, the character xing 行 translates the Sanskrit word krama, while the character jing 經 is influenced by the pronunciation of caṅ-. Kim (2019a, pp. 159–60) proposes that 經行 might initially have been the translation of īryāpatha, which later became specifically associated with caṅkrama. Kim also suggests that it can be interpreted as an emphasis on the intensive form of the Sanskrit word, which is formed by repeating the verb root. |

| 26 | Kim (2019a, pp. 163–65) has discussed the different English translations of the word. |

| 27 | This paragraph has no Pāli parallel, but the shiziwofa 師子臥法 is elucidated in the earlier part of this sūtra as follows: the Beast King, the lion… returns to its cave after foraging. When it desires to sleep, it positions its legs in a piled manner, extends its tail behind, and lies down on its right side. Upon passing the night and reaching dawn, it turns its head to inspect its body (獸王師子……行已入窟,若欲眠時,足足相累,伸尾在後,右脅而臥,過夜平旦,回顧視身。) (T 26 [I], p. 473c12–14). A bhikṣu should emulate this manner of the lion when sleeping. |

| 28 | See the Sarvāstivāda Saṃyukatāgama (Za ahan jing 雜阿含經) (T 99 [II], p. 96): numerous bhikṣus left their quarters to practice mindful pacing in the open air 眾多比丘出房舍外露地經行. |

| 29 | See The Other Translation of Samyuktāgama (Bie yi za ahan jing 別譯雜阿含經) (T 100 [II], p. 381): the śramaṇa Gautama was in Rājagṛha, and in the last part of the night, he practiced mindful pacing in the forest 沙門瞿曇在王舍城,於夜後分,林中經行. |

| 30 | This story appears in at least six versions, in the Sarvāstivāda Saṃyukatāgama (T 99 [II], p. 362), the Vinaya of the Sarvāstivāda (Shi song lü 十誦律) (T.1435 [XXIII], p. 113), The Other Translation of Samyuktāgama (T 100 [II], P.480), the Vinayakṣudraka of the Mūlasarvāstivāda (Genben shuoyi qieyou bu pinaye zashi 根本說一切有部毘奈耶雜事) (T 1451, P.233), the Vinaya of Dharmagupta (Si fen lü 四分律) (T 1428 [XXII], pp. 673b19–c10) and the Pāli Saṃyuttanikāya. The versions in Sarvāstivāda Saṃyukatāgama (T 99) and the Vinaya of the Sarvāstivāda (T 1435) closely resemble each other, while the version in The Other Translation of Saṃyuktāgama (T 100), the Vinayakṣudraka of the Mūlasarvāstivāda (T 1451) and the Vinaya of the Dharmaguptaka presents slight variations. Central to the Sarvāstivāda tradition’s narrative is the scenario in which, during the early part of the night, the Buddha engages in mindful pacing outdoors, with the monk Nāgapāla (xiangshou 象守) serving as his attendant. As the sky threatens rain, Indra magically creats a vaiḍūrya cave or pavilion to shield the Buddha from the rain. The Buddha had been continuously walking, however the Buddha’s attendant Nāgapāla faces a dilemma rooted in the discipline of Buddha’s attendants, which prohibits entry into a room before the Buddha does. Overcome by sleepiness, Nāgapāla resorts to startling the Buddha by announcing the Yakṣa Pojuluo (婆俱羅) was coming, thereby allowing Nāgapāla himself to retire for the night. In the Pāli text, there is also a similar story about Buddha practicing (bhāvanā) in the rain, in which it is the ghost Ajakalāpaka who was trying to frighten the Buddha and the parts regarding the attendant Nāgapāla and Indra were totally non-existent. |

| 31 | See Shi song lü 十誦律 (T 1435 [XXIII], p. 74): at that time, the venerable monks of Ālavī themselves pulled out…the grass in the paths of mindful pacing, and the grass at both ends of the paths of mindful pacing… 爾時阿羅毘諸比丘,自手拔……經行處草、經行兩頭處草…… |

| 32 | See Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya (Genben shuoyiqiyoubu pinaye 根本說一切有部毘那耶) (T 1442 [XXIII], p. 785): at that time, there was a place for mindful pacing where the ground was so hard that it caused injuries to the feet. The Buddha said, “soft grass should be spread so that the feet are not harmed.” After the grass was spread, insects and ants began to appear. The Buddha then said, “it should be abandoned”. 時有經行之處,其地堅鞕令足傷損,佛言,應布軟草勿令傷足。彼布草已,蟲蟻便生,佛言,應棄. |

| 33 | After rising up, he went to the north of the Bodhi tree and practiced mindful pacing for seven days, pacing back and forth over a distance of more than ten paces. Along his path, eighteen distinct flowers appeared. Later, people built a brick platform on this site, standing over three feet high. 其起也,至菩提樹北,七日經行,東西往來,行十餘步,異華隨迹,十有八文。後人於此,壘甎為基,高餘三尺 (Ji et al. 1985, p. 678). |

| 34 | Beside it, there is a mindful pacing path, over seventy paces long, with pippala trees at both the north and south sides. 其側有經行之所,長七十餘步,南北各有卑鉢羅樹 (Ji et al. 1985, p. 686). Pace (bu 步) is a Tang Dynasty unit of length. As mentioned in Jiu tang shu (舊唐書) regulations were established in 627 CE for the measurement of the land. One foot (chi 尺) is around 29.5 cm, five feet make one step, therefore one pace (= two steps) is around 1.475 m. (武德七年,始定律令,以度田之制:五尺為步,步二百四十為畝,畝百為尺). |

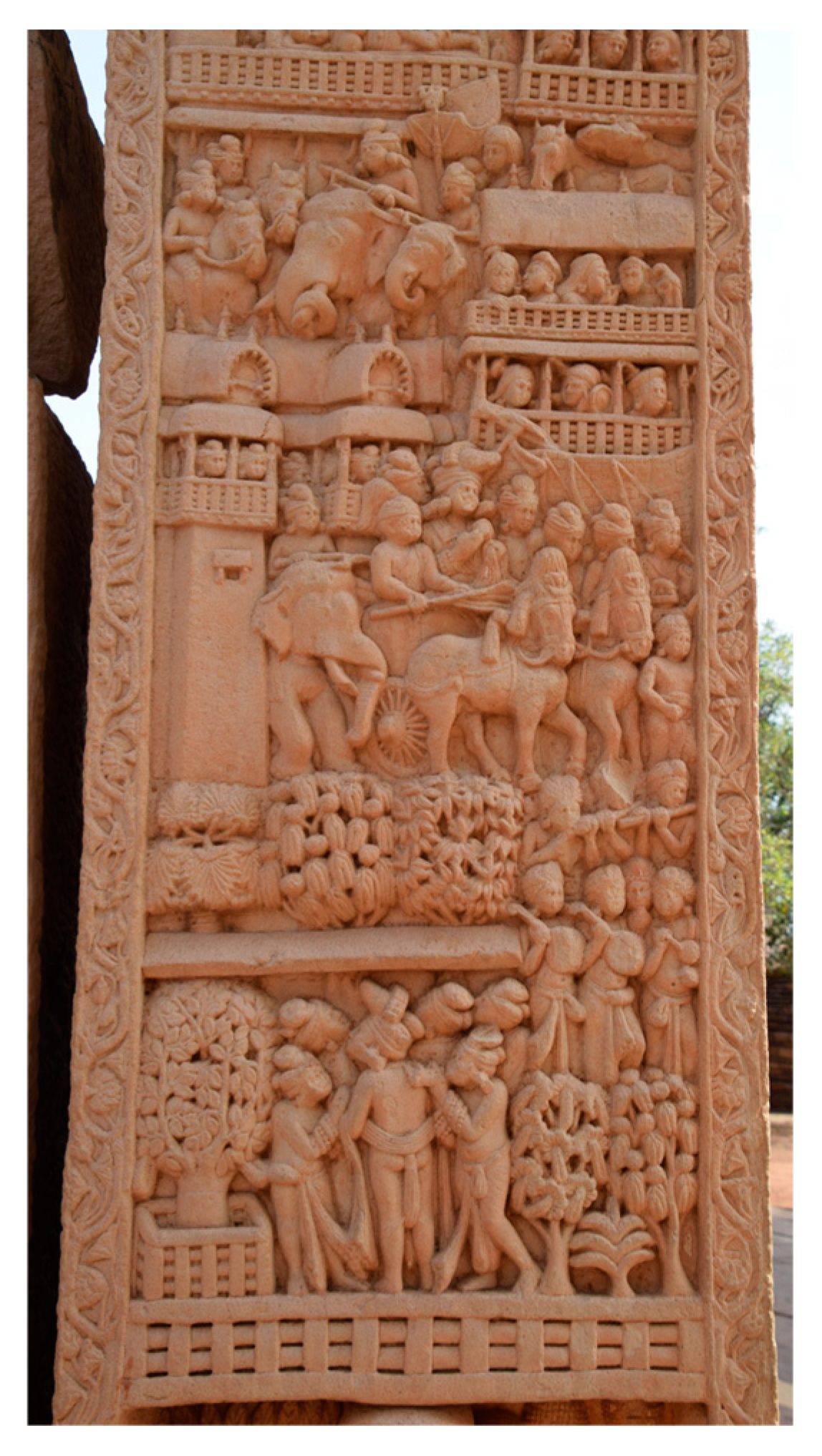

| 35 | In the inscriptions, the term “bodhisattva” is employed. Kim (2019b, p. 207) suggests that this term refers to the Buddha himself prior to his enlightenment. Additionally, it appears that the images are situated on a monument symbolizing the Buddha’s path of mindful pacing. With regard to the inscriptions containing caṃkame (on the promenade), see (Schopen 1997, pp. 244–45; Skinner 2017, pp. 258, 260, 261). |

| 36 | As stated in the Essential Instructions for Practicing Meditation (Chanxiu yaojue 修禪要訣): mindful pacing involves going straight back and forth. How can it be the same as circumambulating? Moreover, a stūpa is a place where many people come and go, making it unsuitable for mindful pacing within. 經行者直往直來,豈同旋遶耶,又塔是多人往來處,不可於中經行. (X 1222 [LXIII], p. 15) |

| 37 | It seems that Buddhapāla is quite confused about why people would have so many questions about mindful pacing as he stated in the Essential instructions for Practicing Meditation (X61, p. 15): practice of mindful pacing is quite common, evident throughout both past and present. There is no need to cause confusion about it 經行之事,蓋是尋常,今古顯然,無宜致惑. |

| 38 | Little attention has been given to meditation districts as essential parts of monasteries. If a meditation district was an essential element of Central Asian monasteries, the presence of meditation caves indicates the presence of a close by monastery. Conversely, once a monastery is identified, the surrounding should be investigated for the possible presence of mediation cells. |

| 39 | This aspect of Kuchean Buddhism received full attention in Howard and Vignato (2015). |

| 40 | Mizuno (1962, 1971); Verardi and Paparatti (2004). The function of several of the corridor-shaped caves shown in these reports could have been meditation caves. |

| 41 |

References

Primary Sources

T. 26 [I]: 421–809. Ven. Gautama Saṅghadeve 瞿曇僧伽提婆 (translator), Zhong ahan jing 中阿含經(Madhyāgama). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T 99 [II]: 1–373. Ven. Guṇabhadra求那跋陀羅 (translator), Za ahan jing 雜阿含經 (Saṃyuktāgama). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T 100 [II]: 374–492. Bieyi za ahan jing 別譯雜阿含經 (The Other Translation of Saṃyuktāgama). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T 1428 [XXII]: 567–1014. Si fen lü 四分律 (Dharmaguptavinaya). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T.1435 [XXIII]: 1–470. Ven. Puṇyatara 弗若多羅 and Kumārajīva 鳩摩羅什 (translator), Shi song lü 十誦律 (Daśabhāṇavāravinaya). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T. 1442 [XXIII]: 627–905. Ven. Yijing 義淨 (translator), Genben shuoyiqieyoubu pinaye 根本說一切有部毗那耶 (Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T. 1451 [XXIV]: 207–414. Ven.Yijing 義淨 (translator), Gebnben shuoyiqieyoubu pinaye zashi 根本說一切有部毘奈耶雜事 (Vinayakṣudraka). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).T. 2053 [L]: 220–280. Ven. Huili慧立, Datang daciensi sanzangfashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 (The Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).X. 1222 [LXIII]: 14–17. Ven. Buddhapāli 佛陀波利 and Mingxun 明恂, Chanxiu yaojue 修禪要訣 (Essential Instructions for Practicing Meditation). Retrieved from https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh (accessed on on 3 June 2024).Secondary Sources

- Al’baum, Lazar’ I. 1974. Raskopki buddijskogo kompleksa Fajaz-tepe (po materialam 1968–1972 gg.). In Drevnjaja Baktrija. Predvaritel’nye Soobščenija ob Archeologičeskich Rabotach na Juge Uzbekistana. Edited by Vadim M. Masson. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Al’baum, Lazar’ I. 1976. Issledovanie Fajaztepe v 1973 g. In Baktrijskie Drevnosti. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Al’baum, Lazar’ I. 1990. Živopis’ svjatilišča Fajaztepa. In Kul’tura Srednego Vostoka: Izobrazitel’noe i Prikladnoe Iskusstvo. Edited by Galina A. Pugačenkova. Tashkent: Nauka, pp. 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Annaev, Džalol, and Tuchtaš Annaev. 2010. Architekturno-planirovočnaja struktura i datirovka buddijskogo monastyr’ja Fajaztepa. In Tradicii Vostoka i Zapada v Antičnoj Kul’tury Srednej Azii: Sbornik Statej v čest’ Polja Bernara. Tashkent: Noshirlik Yog’dusi, pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Samuel. 1906. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. London: Trübner & Co., 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, Caren. 2015. Abenteuer Seidenstraße. Die Berliner Turfan-Expeditionen 1902–1914. Berlin and Leipzig: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin—E.A. Seemann. [Google Scholar]

- Fussman, Gérard. 2011a. Catalogue des Inscriptions sur Poteries, with a Contribution by Nicholas Sims-Williams and in Collaboration with Eric Ollivier, Monuments Bouddhiques de Termez/Termez Buddhist Monuments, Vol. I. Paris: Éditions de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Fussman, Gérard. 2011b. Catalogue des Inscriptions sur Poteries, with a Contribution by Nicholas Sims-Williams and in Collaboration with Eric Ollivier, Monuments Bouddhiques de Termez/Termez Buddhist Monuments, Vol. II. Paris: Éditions de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Grünwedel, Albert. 1912. Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan. Berlin: Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Hallade, Madeleine, and Simone Gaulier. 1967–1982. Douldour-Aqour et Soubachi. (Mission Paul Pelliot: Documents archéologiques, 3–4). Paris: Maisonneuve—Recherches sur les Civilisations, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Angela F., and Giuseppe Vignato. 2015. Archaeological and Visual Sources of Meditation in the Ancient Monasteries of Kuča. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Xianling 季羡林, and et al., eds. 1985. Datang Xiyuji Jiaozhu 大唐西域记校注 [Annotations on the Records of the Western Regions]. Beijing 北京: Zhonghuashuju 中华书局. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Minku. 2019a. Sites of Caṅkrama (Jingxing 經行) in Faxian’s record. Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies 2: 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minku. 2019b. Where the Blessed one Paced Mindfully—The Issue of Caṅkrama on Mathurā’s Earliest Freestanding Images of Buddha. Achives of Asian Art 69: 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Li 林立. 2018. Xiyu Gu Fosi—Xinjiang Gudai Dimian Fosi Yanjiu 西域古佛寺—新疆古代地面佛寺研究 [Ancient Buddhist Temples of the Western Regions—A Study of Ancient Ground-Level Buddhist Temples in Xinjiang]. Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Muzio, Ciro. 2012. Remarks on the Paintings from the Buddhist Monastery of Fayaz Tepe (Southern Uzbekistan). Bulletin of the Asia Institute 22: 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Muzio, Ciro. 2017. Archeologia Dell’Asia Centrale Preislamica. Dall’età del Bronzo al IX Secolo d.C. Milano: Mondadori Università. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Seiichi, ed. 1962. Haibak and Kashmir-Smast. Survey of Cave Temples in Afghanistan and Pakistan 1960. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Seiichi, ed. 1971. Basawal and Jelalabad-Kabul. Buddhist Cave-Temples and Topes in Southeast Afghanistan, Surveyed Mainly in 1965. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Wanli 冉万里. 2020. Xinjiang Kuche Subashi Fosi Yizhi Shiku Diaocha Baogao 新疆库车苏巴什佛寺遗址石窟调查报告 [Investigation Report on the Caves of the Subashi Buddhist Temple Site in Kucha, Xinjiang]. Shanghai: Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Rhie, Marilyn. 1999–2002. Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia. Leiden, Boston and Köln: Brill, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Fan 桑梵. 2021. Xinjiang Subashi Fosi Jianzhu Xingzhi Yanjiu 新疆苏巴什佛寺建筑形制研究 [A Study of the Architectural Forms of the Subashi Buddhist Temple in Xinjiang]. Master’s dissertation, Architettura, Università Sudorientale, Nanjing. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 1997. Bones, Stones and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India. Honolulu: University of Huwai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 2008. On Emptying Chamber Pots without Looking and the Urban Location of Buddhist Nunneries in Early India again. Journal Asiatique 2: 229–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, Michael C. 2017. Marks of Empire: Extracting a Narrative from the Corpus of Kuṣāṇa Inscriptions. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskii, Boris, and Tigran Mkrtychev. 1996. Qara-Tepe in Old Termez. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 10: 219–32. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja. 1986. La Bactriane Sous Les Kushans. Problèmes D’histoire et de Culture. Paris: Jean Maisonneuve. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja, ed. 1969. Buddijskie Peščery Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze. Osnovnye Itogi Rabot 1963–1964. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja, ed. 1972. Buddhijskij Kul’tovij Centr Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze. Osnovnye Itogi Rabot 1965–1971 gg. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja, ed. 1975. Novye Nachodki na Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze. Osnovnye Itogi Rabot 1972–1973 gg. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja, ed. 1982. Buddijskie Pamjatniki Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze, Osnovnye Itogi Rabot 1974–1977. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja, ed. 1996. Buddijskie Kompleksy Kara-Tepe v Starom Termeze. Osnovnye Itogi Rabot 1978–1989 gg. Moskva: Vostočnaja Literatura. [Google Scholar]

- Staviskij, Boris Ja, Evgenija V. Pčelina, and Tat’jana V. Grek, eds. 1964. Kara-Tepe–Buddijskij Peščernyj Monastyr’ v Starom Termeze. Osnovnye Itogi Rabot 1937, 1961–1962 gg. i Indijskie Nadpisi na Keramike. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Verardi, Giovanni, and Elio Paparatti. 2004. Buddhist Caves of Jāghūrī and Qarabāgh–e Ghaznī, Afghanistan. Rome: IsIAO. [Google Scholar]

- Vignato, Giuseppe. 2005. Kizil: Characteristics and Development of the Groups of Caves in Western Guxi. Annali Dell’Università Degli Studi di Napoli “l’Orientale” 65: 121–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vignato, Giuseppe. 2006. Archaeological Survey of Kizil: Its Groups of Caves, Districts, Chronology and Buddhist Schools. East and West 56: 359–416. [Google Scholar]

- Vignato, Giuseppe. 2023. Solids and Voids in the Rock Monasteries of Kucha. International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture 33: 165–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignato, Giuseppe, and Alice Casalini. 2022. A failed transmission?: The case of the Kucha type central pillar caves. Rivista Degli Studi Orientali XCV: 259–84. [Google Scholar]

- Vignato, Giuseppe, and Satomi Hiyama. 2022. Traces of the Sarvāstivādins in the Buddhist Monasteries of Kucha. New Delhi: Dev Publishers & Distributors. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qian 王倩, and Giuseppe Vignato. Forthcoming. Qiuci biciuni zhuju hechu? xingbie kaogu shijiaoxia de qiuci shikusi 龟兹比丘尼住居何处?——性别考古视角下的龟兹石窟寺 [Where Did the Kucha bhikṣuṇīs Reside?—Kucha Cave Temples from the Perspective of Gender Archaeology]. Religions. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Zhengzhong 魏正中. 2013. Quduan yu Zuhe—Qiuci Shiku Siyuan Yizhi de Kaoguxue Tansuo 区段与组合:龟兹石窟寺院遗址的考古学探索 [Districts and Grups—Indagine Archeologica sui Monasteri Rupestri di Kucha]. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, William Dwight. 1889. Sanskrit Grammar. Leipzig: Breitk Opf and Härtel. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Lidong 夏立栋. 2023. Qushi Gaochangguo Biguanku Chutan麴氏高昌国“闭关窟”初探 [Preliminary Study on the ‘silent retreat Caves’ of the Qushi Gaochang]. Dunhuangxue Jikan 敦煌学辑刊 4: 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Ping 张平. 2010. Qiuci Wenming—Qiuci Shidi Kaogu Yanjiu 龟兹文明—龟兹实地考古研究 [The Civilization of Kucha—Field Archaeological Research on Kucha]. Beijing: Renmin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Qinlan 赵青兰. 1995. Tamiaoku de kuxing yanbian ji qi xingzhi 塔庙窟的窟形演变及其性质 [L’evoluzione della forma e della natura delle grotte nel sito rupestre di Tamiao]. In Dunhuang Shiku Yanjiu Guoji Taolunhui Wenji 敦煌石窟研究国际讨论会文. Edited by Wenjie Duan 段文杰. Shenyang: Liaoning Meishu Chubanshe, vol. 1, pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Qinzhi 朱慶之. 1992. Fodian Yu Zhonggu Hanyu Cihui Yanjiu 佛典與中古漢語詞彙研究 [A Study of Buddhist Texts and Medieval Chinese Vocabulary]. Taibei: Wenjing Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vignato, G.; Li, X. Kucha and Termez—Caves for Mindful Pacing and Seated Meditation. Religions 2024, 15, 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081003

Vignato G, Li X. Kucha and Termez—Caves for Mindful Pacing and Seated Meditation. Religions. 2024; 15(8):1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081003

Chicago/Turabian StyleVignato, Giuseppe, and Xiaonan Li. 2024. "Kucha and Termez—Caves for Mindful Pacing and Seated Meditation" Religions 15, no. 8: 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081003

APA StyleVignato, G., & Li, X. (2024). Kucha and Termez—Caves for Mindful Pacing and Seated Meditation. Religions, 15(8), 1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081003