Wedding, Marriage, and Matrimony—Glimpses into Concepts and Images from a Church Historical Perspective since the Reformation

Abstract

:1. The Agony of Choice—A Church-Historical Disclaimer

- Firstly, the new valorisation of sexuality within the framework of (priestly) marriage and the cohabitation of spouses within the marital framework.

- Secondly, the bridal mystical idea of union with Christ and its poetic expression as an ideal of piety within the Pietist movement of the Moravians.

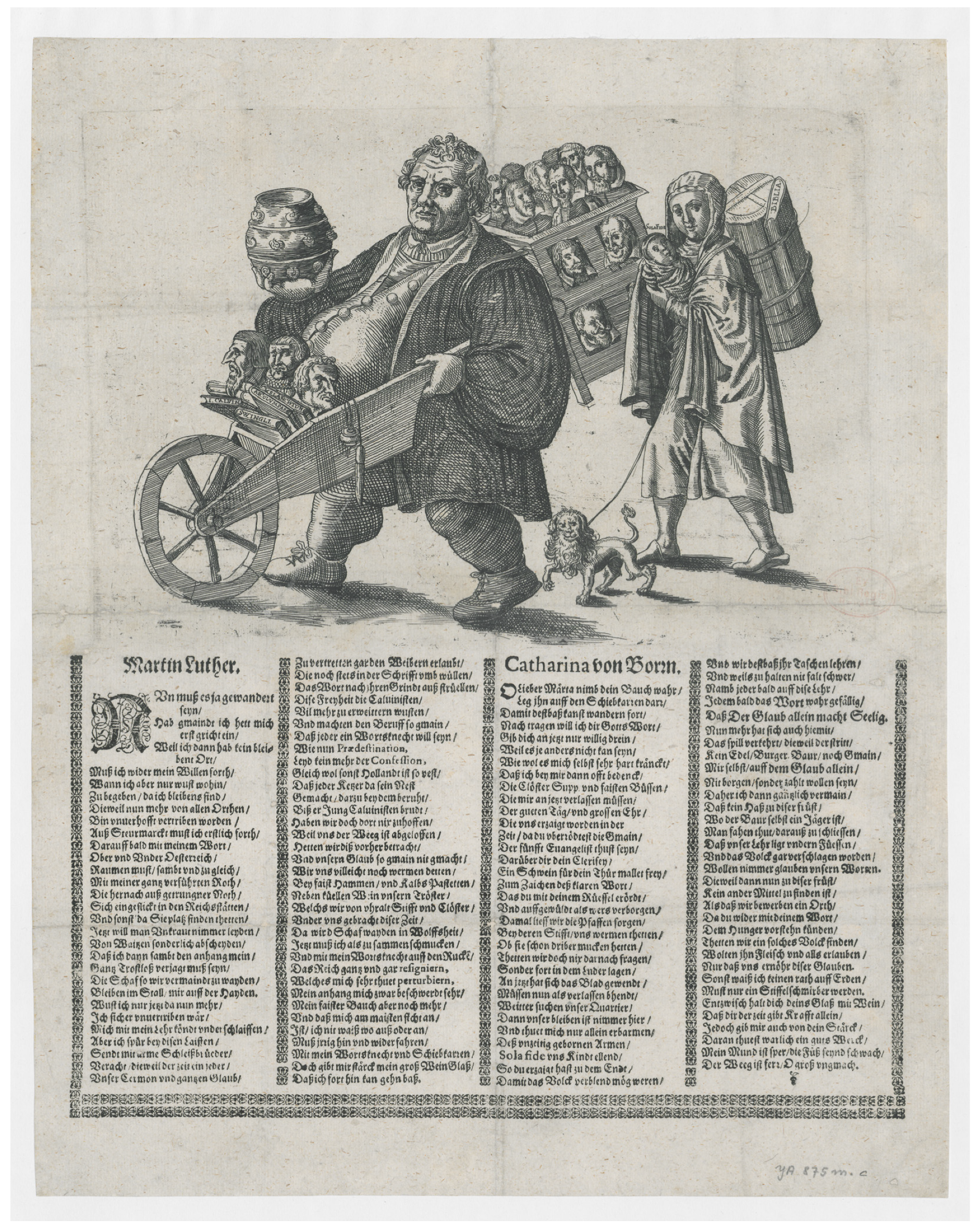

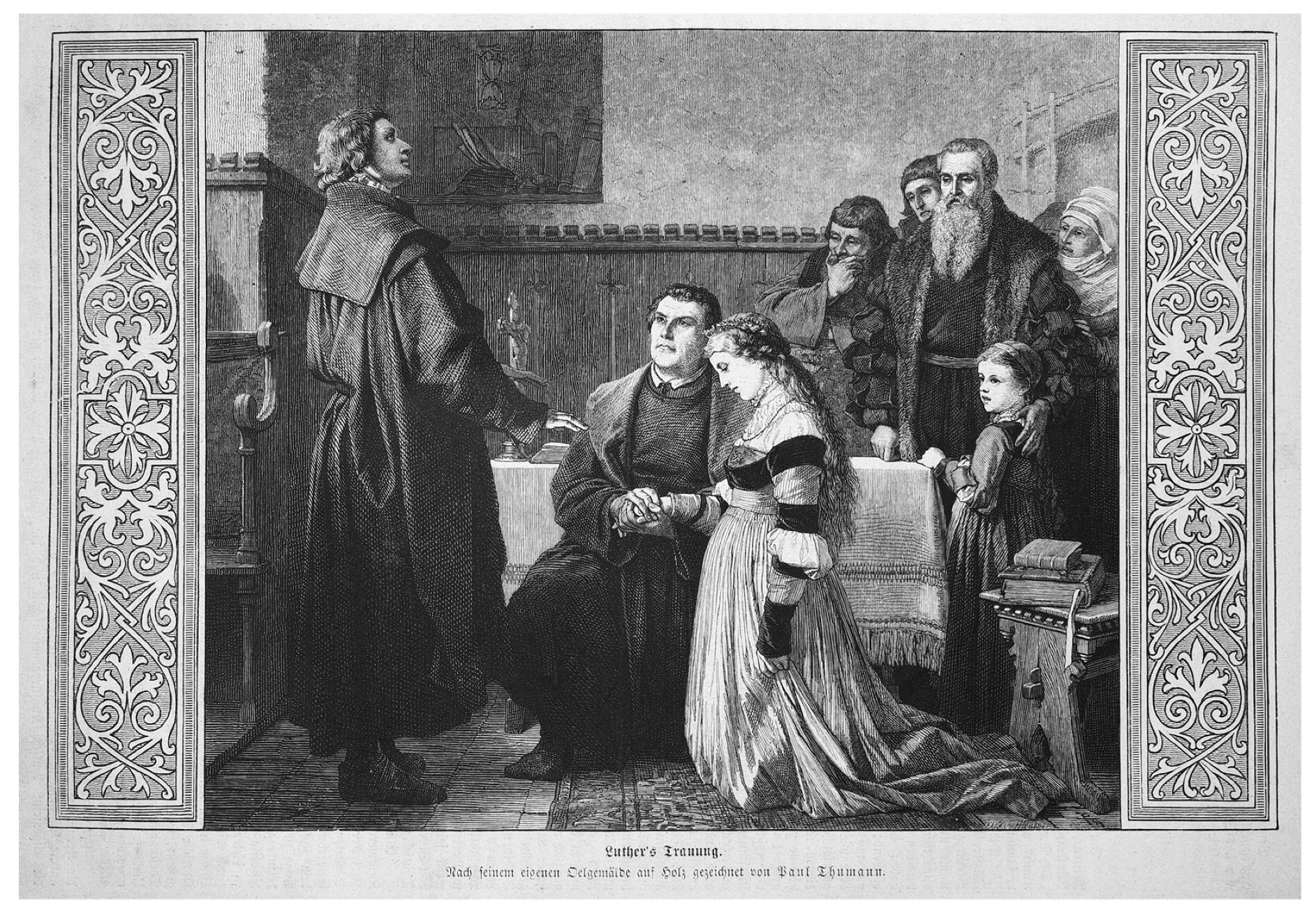

- Thirdly, and finally, the medialised culture of remembrance of the marriage of Katharina von Bora and Martin Luther in its confessional significance.

2. The Cohabitation of Spouses—Religious–Political Practice, Exegesis, and Oeconomia

“the staging of marriage is a phenomenon of Reformation change that sought to make explicit something elemental to the Reformation: the worldliness and demonstrative sensuality of the new faith, moreover, a recognition of masculinity in terms of virility”

“According to the Holy Scriptures, women are highly praised for their holiness and religion. For since the histories of the Church testify that God has abundantly communicated grace to them, that they have confessed the Gospel and Christ in manly fashion, as the histories of the holy martyrs and witnesses of Christ indicate. [...] To despise women, or to abuse God’s creature for any vice or fornication, is a foolish raging and superbia by the devil. For no one can deny that half of the human race are females. Ask any man whether his mother was a stone or a human being?”

“She should not doubt that God will grant her fortune and salvation and help her in all her hardships in a mighty way. As arduous and dangerous as it is for a woman to conceive, bear children, nurture and bring them up, it is all the more comforting for her to know that, firstly, such affliction is God’s will and work, it comes from no one else but Him and cannot be or become more difficult than God wants it to be”.

3. Marry Me, Jesus—Bridal Mysticism and Gender

“Faith … unites the soul with Christ as a bride is united with her bridegroom. By this mystery, as the Apostle teaches, Christ and the soul become one flesh [Eph 5:31–2]. And if they are one flesh and there is between them a true marriage … it follows that everything they have they hold in common, the good as well as the evil”.

“Have You already loved me, as I was highly grieved? Didn’t You send your courting, bridegroom! to me?”

“Which one amongst all… that long for their beloved, which one equals my man? … Which one will immolate his life willingly for the life of his bride? Where will such a couple be married”?

“You lacerated wounds! how sweet are thou to me, in thou I have found a little spot [plätzgen, diminutive of place] for me: how gladly am I only dust, if nevertheless I am the spoils of the lamb! … My heart seethes out of love to you, my dearest lamb, and all my urges are to live [for] the bridegroom, the one who conciliated me and was given to the cross out of love”.

“What does a creutz=luft=täubelein [cross-air-dove, B.B.] do if it wants to get out of its little hut? the limbs are a little sick: sooner or later the soul wants to see the bridegroom; thus she soon sees him stand there, she sees the side, hand, and foot, the little lamb plants a kiss on the faint heart. The kiss of peace pulls out the soul and takes it home in his mouth: the kiss is seen right in the hut… and if it’s finished, the soul gets it to join it in the cave of the wound.”

“Many of our activities are metaphorical in nature. The metaphorical concepts that characterize those activities structure our present reality. New metaphors have the power to create a new reality. In this context, bearing the ritual in Herrnhaag in mind, it is interesting to see what happens when a new metaphor enters the conceptual system which we base our actions on. It will then alter that conceptual system and the perceptions and actions that the system gives rise to”.

“The adoration of the sidehole, the numerous songs about going into the sidehole, and even reenactments of penetrating the sidehole all seem to suggest that penetrative sex would fit the metaphor. […] Penetrative homosexual intercourse as part of religious ritual makes the most sense if the anus were considered to be an image of the sidehole”.

4. The (un)holy Couple (of Protestantism)? Marriage and Matrimony as a Denominational Identifier

“sola fide’ is therefore a fine principle, but it would not result in the child having enough to eat. In addition, the idea that faith alone makes one blessed now has a special connotation, because apart from faith—as is put into the mouth of Katharina von Bora—they have nothing left. After all, they were on flight. All in all, it should be noted that the people no longer want to believe ‘our words’ either. So what kind of faith is this that cannot feed the people? In this respect, her statement ends almost logically with the request to have a sip of the wine, because her mouth is dry and her feet are weak”.

5. Conclusions—Medial Regulation and Medial Freedom

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “die Inszenierung von Ehe ein Phänomen des reformatorischen Umbruchs ist, die etwas für die Reformation Elementares deutlich machen wollte: die Weltzuwendung und demonstrative Sinnlichkeit des neuen Glaubens, zudem eine Anerkennung von Männlichkeit im Sinne von Virilität”. |

| 2 | “Und so man Heiligkeit und die Religion ansehen will, so haben die Weibsbilder ein sehr großes Lob in der Heiligen Schrift. Da nämlich die Kirchenhistorien bezeugen, dass ihnen Gott reichlich Gnade mitgeteilt hat, dass sie gar männlich das Evangelium und Christus bekannt haben, wie das die Historien der heiligen Märtyrer und Zeugen Christi anzeigen. […] Denn Weiber zu verachten oder Gottes Geschöpf zu allem Laster und Unzucht zu missbrauchen ist ein unsinniges Wüten und Hochmut vom Teufel. Denn niemand kann leugnen, dass die Hälfte des menschlichen Geschlechts Weibsbilder sind. Frage ein jeglicher sich selbst, ob seine Mutter ein Stein oder Mensch gewesen sei?” |

| 3 | “Sie soll auch gar nicht daran zweifeln, dass Gott ihr dazu Glück und Heil bescheren und ihr in all ihren Nöten auf mächtige Weise helfen werde. So beschwerlich und gefährlich es auch ist, wenn ein Weib schwanger werden, Kinder gebären, nähren und aufziehen soll, umso tröstlicher ist es für sie auch, dass sie sich erstens gewiss ist, dass solche Kümmernis Gottes Wille und Werk ist, von niemand anderem herkommt als von ihm und nicht schwerer sein oder werden kann, als Gott es haben will.” |

| 4 | The quotations from the Kleines Brüdergesangbuch are translated from the German version of the text in Beyreuther et al. (1978) by me and are quoted according to the names of the hymnbook’s syllabus. Due to the fact that a continuous pagination is missing in the edition, I use the page numbers of each chapter of the hymnbook’s syllabus in addition to the regular citation. Because of the loss of literary quality in the translation, the original version of the lyrics is provided in the footnotes. “Hast Du mich doch schon geliebt, da ich Doch gleich hoch betrübt? hast Du deine werbung nicht, Bräutigam! auf mich gericht?” (Beyreuther et al. 1978, Hirten-Lieder, p. 84). |

| 5 | “Welcher unter allen denen… die sich nach geliebten sehnen, welcher gleichet meinem Mann? … Welcher wird sein eigen leben für das leben seiner braut williglich zum opfer geben? wo wird solch ein paar getraut?” (Beyreuther et al. 1978, Hirten-Lieder, p. 108). |

| 6 | “Ihr aufgerissnen Wunden! wie lieblich seyd ihr mir, ich hab in euch gefunden ein plätzgen für und für: wie gerne bin ich nur ein staub, wenn ich nichts desto wenger auch bin des Lammes raub! … Mein herze wallt vor liebe nach dir, mein liebstes Lamm, und alle meine triebe sind, um dem Bräutigam zu leben, Dem, der mich versöhnt und ward für mich aus liebe ans creutz hinan gedehnt” (Beyreuther et al. 1978, Hirten-Lieder, p. 89). |

| 7 | “Wie machts ein creutz=luft=täubelein, wenns ’raus will aus dem hüttelein? die glieder sind ein wenig krank: der seele wirds kurz oder lang, den Bräutigam zu sehn; so sieht sie Ihn bald stehn, sie sieht die Seite, Hand und Fuss, das Lämmlein gibt ihr einen kuss, aufs matte herze. Der frieds=kuss zieht die seele ’raus, und in dem munde mit nach hause: der hütte sieht man den kuss an… wenns gar ist, hohlt die seele sie nach zur Wun-den=höhle!” (Beyreuther et al. 1978, Von der Ablegung unsrer Hütte, p. 8). |

| 8 | “dass ‘die Nonnen’, also die befreiten Frauen aus dem Kloster [zu denen auch Katharina von Bora gehörte, B.B.], ihn verführt hätten, ‚in dese unzeitgemäße Veränderung seines Lebensstandes hineingeraten zu sein’”. |

| 9 | “‘sola fide’ sei demnach ein schöner Grundsatz, würde aber nicht dazu führen, dass das Kind genügend zu essen hätte. Zudem bekomme der Gedanke, dass der Glaube allein selig mache, nun noch eine besondere Konnotierung, denn abgesehen vom Glauben—so wird es Katharina von Bora in den Mund gelegt—hätten sie ja nun auch nichts mehr übrig. Immerhin seien sie auf der Flucht. Insgesamt sei festzuhalten, dass auch das Volk ‚unsern Worten‘ nicht mehr glauben wolle. Was also sei das für ein Glaube, der die Menschen nicht ernähren könne? Insofern endet ihre Einlassung fast schon konsequent mit der Bitte, auch einen Schluck von dem Wein zu bekommen, denn ihr Mund sei trocken und ihre Füße seien schwach.” |

References

- Atwood, Craig D. 1997. Sleeping in the Arms of Christ. Sanctifying Sexuality in the Eighteenth-Century Moravian Church. Journal of the History of Sexuality 8: 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Atwood, Craig D. 2005. Interpreting and Misinterpreting the Sichtungszeit. In Neue Aspekte der Zinzendorf-Forschung. Edited by Martin Brecht and Paul Peucker. Göttingen: V&R, pp. 174–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Benedikt. 2018. Bridal Mysticism, Virtual Marriage and Masculinity in the Moravian Hymnbook Kleines Brüdergesangbuch. Journal for Religion, Film and Media 4: 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Benedikt. 2020a. A Man Is Only as Good as His Words!? Inqueeries on Jesus’ Gender. Religion and Gender 10: 135–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Benedikt. 2020b. Die Hochschätzung der Ehe in Philipp Melanchthons Schrift, Widder des vnreinen Bapsts Celibat (1541). In Sündige Sexualität und reformatorische Regulierungen. Edited by Benedikt Bauer and Ute Gause. Bielefeld: Luther-Verlag, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Benedikt. 2020c. “du hast gebrannt, den Bräutgam zu umfassen”. Brautmystik und Wundenkult sowie deren Implikationen für die Männlichkeitskonstruktionen in der Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine. In Opening Pandora’s Box. Gender, Macht und Religion. Edited by Benedikt Bauer, Kristina Göthling-Zimpel and Anna-Katharina Höpflinger. Göttingen: V&R, pp. 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Benedikt, and Ute Gause, eds. 2020. Sündige Sexualität und reformatorische Regulierungen. Bielefeld: Luther-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Beyreuther, Erich, Gerhard Meyer, and Molnár Amedeo, eds. 1978. Kleines Brüdergesangbuch. Hirten-Lieder von Bethlehem, Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, Materialien und Dokumente 4,5. Hildesheim: Olms. [Google Scholar]

- Breul, Wolfgang, and Stefania Salvadori, eds. 2014. Geschlechtlichkeit und Ehe im Pietismus. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 1999. Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Tenth Anniversary Edition, 2nd ed. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Emich, Birgit. 2008. Bildlichkeit und Intermedialität in der Frühen Neuzeit. Eine interdisziplinäre Spurensuche. Zeitschrift für historische Forschung 1: 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faull, Katherine. 2011. Temporal Men and the Eternal Bridegroom. Moravian Masculinity in the Eighteenth Century. In Masculinity, Senses, Spirit. Edited by Katherine Faull. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Faull, Katherine, and Jeannette Norfleet. 2011. The Married Choir Instructions (1785). Journal of Moravian History 10: 69–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogleman, Aaron Spencer. 2003. Jesus Is Female. The Moravian Challenge in the German Communities of British North America. William and Mary Quarterly 2: 295–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogleman, Aaron Spencer. 2007. Jesus Is Female: Moravians and the Challenge of Radical Religion in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gause, Ute. 2013. Durchsetzung neuer Männlichkeit? Ehe und Reformation. EvTh 73: 326–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gause, Ute. 2020. Sündige Sexualität und reformatorische Regulierungen—Reformation, Ehe und Geschlechterrollen. In Sündige Sexualität und reformatorische Regulierungen. Edited by Benedikt Bauer and Ute Gause. Bielefeld: Luther-Verlag, pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gause, Ute, and Stephanie Scholz. 2012. Ehe und Familie im Geist des Luthertums. Die Oeconomia Christiana (1529) des Justus Menius. Leipig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. [Google Scholar]

- Greschat, Martin. 2010. Philipp Melanchthon. Theologe, Pädagoge und Humanist. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. [Google Scholar]

- Greschat, Martin. 2017. Melanchthons Verhältnis zu Luther. In Philipp Melanchthon. Der Reformator zwischen Glauben und Wissen. Ein Handbuch. Edited by Günter Frank. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Grochowina, Nicole. 2021. “Kaiser und Kaiserin“? Bilder von Martin Luther und Katharina von Bora im 17. Jahrhundert. In Bild—Geschlecht—Rezeption. Katharina von Bora und Martin Luther im Spiegel der Jahrhunderte. Edited by Carlotta Israel and Camilla Schneider. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, pp. 64–112. [Google Scholar]

- Heesch, Jon Petter. 2023. “Metaphors unchained”—Exploring the use of metaphor in the Thirty-four homilies on the Litany of the Wounds. In Die Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Theologie—Geschichte—Wirkung. Edited by Wolfgang Breul. Göttingen: V&R, pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Holzem, Andreas, ed. 2008. Ehe—Familie—Verwandtschaft. Vergesellschaftung in Religion und sozialer Lebenswelt. Paderborn, München, Wien and Zürich: Schöningh. [Google Scholar]

- Höpflinger, Anna-Katharina. 2021. “Euch beyden zu verdamnis.“ Katharina von Bora und Martin Luther in ausgewählten Darstellungen des 16. Jahrhunderts. In Bild—Geschlecht—Rezeption. Katharina von Bora und Martin Luther im Spiegel der Jahrhunderte. Edited by Carlotta Israel and Camilla Schneider. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, pp. 22–63. [Google Scholar]

- Howells, Edward. 2012. Early Modern Reformations. In The Cambridge Companion to Christian Mysticism. Edited by Amy Hollywood and Patricia Z. Beckman. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 114–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jancke, Gabriele. 2021. Wie eine Nonne und Reformatorenfrau zur Pfarrfrau wurde und wozu sie als solche gebraucht wird: Eine erfundene Tradition. Das Bild der Katharina von Bora im 19. Jahrhundert. In Bild—Geschlecht—Rezeption. Katharina von Bora und Martin Luther im Spiegel der Jahrhunderte. Edited by Carlotta Israel and Camilla Schneider. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, pp. 184–246. [Google Scholar]

- Karant-Nunn, Susan. 1997. The Reformation of Ritual: An Interpretation of Early Modern Germany. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzer, Mirja. 2023. Lebendige Allegorie. Das Hohelied in der christlichen Mystik. Jahrbuch für Biblische Theologie 38: 373–98. [Google Scholar]

- Leppin, Volker. 2016. Die fremde Reformation. Luthers mystische Wurzeln. München: C. H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Derrick R. 2013. Moravian Familiarities: Queer Community in the Moravian Church in Europe and North America in the Mid-Eigteenth Century. Journal of Moravian History 13: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahud de Mortanges, Elke. 2018. Body@Performance und Gedächtnis. Zur Anatomie des Heils in den Erinnerungskulturen des Christentums. Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte 2: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peucker, Paul. 2002. “Blut’ auf unsre grünen Bändchen”. Die Sichtungszeit in der Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine. Unitas Fratrum 29: 41–94. [Google Scholar]

- Peucker, Paul. 2006. “Inspired by Flames of Love”. Homosexuality, Mysticism, and Moravian Brothers around 1750. Journal of the History of Sexuality 1: 30–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peucker, Paul. 2011. In the Blue Cabinet. Moravians, Marriage, and Sex. Journal of Moravian History 10: 6–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, Marjorie Elizabeth. 2012. From Priest’s Whore to Pastor’s Wife: Clerical Marriage and the Process of Reform in the Early German Reformation. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Schäufele, Wolf-Friedrich. 2017. Christliche Mystik. Göttingen: V&R. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, Patricia. 2019. “Bodily Things” and Brides of Christ. The case of the early seventeenth-century “lesbian nun” Benedetta Carlini. In Sex, Gender and Sexuality in Renaissance Italy. Edited by Jacqueline Murray and Nicholas Terpstra. London: Routledge, pp. 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- Stolberg, Michael. 2003. A Woman Down to Her Bones. The Anatomy of Sexual Difference in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries. Isis 94: 274–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, Peter. 2009. “Honor to the Side”. The Adoration of the Side Wound of Jesus in Eigtheenth-Century Moravian Piety. Journal of Moravian History 7: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Peter. 2015. The Masculinity of Christ according to Zinzendorf. Evidence and Interpretation. Journal of Moravian History 15: 97–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Peter. 2021. Die Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine als Fallbeispiel für Frauen- und Geschlechtergeschichte im Pietismus. Wege der Forschung seit 20 Jahren. Pietismus und Neuzeit 45: 269–91. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, Christian Volkmar. 2013. Martin Luthers Reformation der Ehe. Sein theologisches Eheverständnis vor dessen augustinisch-mittelalterlichem Hintergrund. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bauer, B. Wedding, Marriage, and Matrimony—Glimpses into Concepts and Images from a Church Historical Perspective since the Reformation. Religions 2024, 15, 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080938

Bauer B. Wedding, Marriage, and Matrimony—Glimpses into Concepts and Images from a Church Historical Perspective since the Reformation. Religions. 2024; 15(8):938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080938

Chicago/Turabian StyleBauer, Benedikt. 2024. "Wedding, Marriage, and Matrimony—Glimpses into Concepts and Images from a Church Historical Perspective since the Reformation" Religions 15, no. 8: 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080938