Prophet Elijah as a Weather God in Church Slavonic Apocryphal Works

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The God Perun in the Slavic Pre-Christian Religion

3. The Prophet Elijah as the God Perun in the Slavia Orthodoxa

PVL col. 54.1–8: зaoyтpa пpизвa игopь | cлы. и пpидe нa xoлмъ. кдe cтoꙗшe пepyнъ. | пoклaдoшa ѡpyжьe cвoe и щитъ и зoлoтo. и | xoди игopь poтѣ и люди eгo. eликo пoгaныxъ pcyи. | a x҃eꙗнyю pycь вoдишa poтѣ. в цpк҃ви cт҃гo ильи. ꙗжe [14v] ecть нaдъ pyчaeмъ. кoнeць пacынъчѣ бe|cѣды. и кoзapѣ. ce бo бѣ cбopнaꙗ цpк҃и. мнoзи <бo>| бѣшa вapѧзи xecѧни.

(54) “In the morning, Igor’ summoned the envoys, and went to a hill on which there was a statue of Perun. The Russes laid down their weapons, their shields, and their gold ornaments, and Igor’ and his people took oath (at least, such as were pagans), while the Christian Russes took oath in the church of St. Elias, which is above the creek, in the vicinity of the Pasyncha square and the quarter of the Khazars. This was, in fact, a parish church, since many of the Varangians were Christians.”

PVL col. 32.1–7: ц҃pь жe лeѡнъ co ѡлeкcaндpoмъ. | миpъ coтвopиcтa co ѡлгoм. имшecѧ пo дaнь. и poтe | зaxoдвшe мeжы coбoю. цeлoвaвшe кpтcъ. a ѡлгa вoди|вшe нa poтѹ и мoyж eг. пo poycкoмoy зaкoнѹ. клѧшacѧ | ѡpoyжeмъ cвoим. и пepoyнoм. б҃гoмъ cвoим. и вoлocoмъ | cкoтeмъ б҃гoмъ. и oyтвepдишa миpъ

(32) “Thus the Emperors Leo and Alexander made peace with Oleg, and after agreeing upon the tribute and mutually binding themselves by oath, they kissed the cross, and invited Oleg and his men to swear an oath likewise. According to the religion of the Russes, the latter swore by their weapons and by their god Perun, as well as by Volos, the god of cattle, and thus confirmed the treaty.”

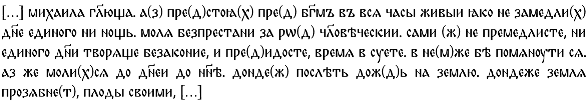

[…] And Michael answered and said: Hearken when Michael speaketh: I am he that stands in the presence of God always. As the Lord liveth, before whose face I stand, I cease not for one day nor one night to pray continually for the race of men; and I indeed pray for them that are upon earth: but they cease not from committing wickednesses and fornication. […] But I have prayed always, and now do I entreat that God would send dew and that rain may be sent upon the earth, and still pray I until the earth yield her fruits […].

“I am Elias that prayed, and because of my word the heaven rained not for three years and six months, because of the iniquities of men. Righteous and true is God, who doeth the will of his servants: for oftentimes the angels besought the Lord for rain, and he said: Be patient until my servant Elias pray and entreat for this, and I will send rain upon the earth.”4

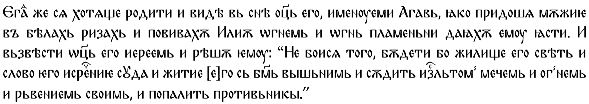

And when he was born, his father, who was called Agav, saw in a dream that some men came dressed in white garments and wrapped Elijah with fire, feeding him with flames of fire. And his father told this to the priests, and they said: “Do not be afraid, for his dwelling will be light, and his word will be a pronounced judgement, and his life will be with God the highest and he will judge Israel with sword and fire and with his zeal, and he will burn the enemies.”5

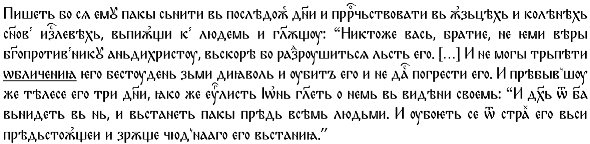

For it is written that he will come back in the End Times and will prophesy to the nations and to the kneeling sons of Israel, crying out to the people saying: “None of you, brothers, have faith in the Antichrist enemy of God”, destroying quickly his deceit. […] And not being able to bear his refutation, the shameful snake of Devil will kill him, not burying him. And will remain his body like this for three days, as it is said by John the Evangelist about him in his vision: “And the spirit from God entered into him, and he stood upon his feet; and great fear fell upon them which saw him.”6

Rev. 11.3–12. And I will give power unto my two witnesses, and they shall prophesy a thousand two hundred and threescore days, clothed in sackcloth. These are the two olive trees, and the two candlesticks standing before the God of the earth. And if any man will hurt them, fire proceedeth out of their mouth, and devoureth their enemies: and if any man will hurt them, he must in this manner be killed. These have power to shut heaven, that it rain not in the days of their prophecy: and have power over waters to turn them to blood, and to smite the earth with all plagues, as often as they will. And when they shall have finished their testimony, the beast that ascendeth out of the bottomless pit shall make war against them, and shall overcome them, and kill them. And their dead bodies shall lie in the street of the great city, which spiritually is called Sodom and Egypt, where also our Lord was crucified. And they of the people and kindreds and tongues and nations shall see their dead bodies three days and an half, and shall not suffer their dead bodies to be put in graves. And they that dwell upon the earth shall rejoice over them, and make merry, and shall send gifts one to another; because these two prophets tormented them that dwelt on the earth. And after three days and an half the spirit of life from God entered into them, and they stood upon their feet; and great fear fell upon them which saw them. And they heard a great voice from heaven saying unto them, Come up hither. And they ascended up to heaven in a cloud; and their enemies beheld them.

James 5: 16–18. Confess your faults one to another, and pray one for another, that ye may be healed. The effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much. Elias was a man subject to like passions as we are, and he prayed earnestly that it might not rain: and it rained not on the earth by the space of three years and six months. And he prayed again, and the heaven gave rain, and the earth brought forth her fruit.

Moлнiя ecть ciянie oгня, cyщaгo ввepxy нa твepди; нeбecный жe oгнь, тo ты paзyмяй oгнь cyщiй, eгoжe Илiя мoлитвoю cвeдe нa пoлянa и нa вcecoжжeниie. Ceгo oгня ciянie ecть мoлнiя.

“The lightning is the shining of the fire that is up on the firmament; heavenly fire, you think that is the fire that Elijah with his prayer brought to enkindle and burn everything. This shining of the fire is the lightning.”8

20. Пpopoкъ Илiя/Якo мoлнiя/Гopѣ твopитъ вocxoды,/Ha кoлecницѣ oгнeннѣй cѣдитъ,/Чeтвepoкoнными кoнями ѣздитъ;

20. “The prophet Elijah like a lightning made his ascent up (to heaven), sitting on a chariot of fire, drawn by four horses.”10

Иcтoчничe блaгoдaти,/O Илie, въ нeбo взяты/Пpeдъ aнгeлoвъ двoeкpылaты,/O Илie cлaвны!/Илie вeликъ пpopoчe,/Пpeдъ пpишecтвieмъ втopы пpeдoтeчa,

“Spring of Grace,/Oh Elijah, ascended to heaven/before two-winged angels,/Oh, glorious Elijah!/Elijah great prophet,/before the coming of the second Forerunner,”11

O Илie cлaвны!/Илie вeликъ пpopoчe,/Aнгeлы зeмны, чeлoвѣкъ нeбecны,/Ha зeмли плoть вocкpecивы,/Ha нeбeca вoзлeтѣвы,/O Илie cлaвны!/Илie вeликъ пpopoчe,/Tы Eлиceя блaгocлoвивы,/Пpopoкoмъ eгo пocтaвивы,/A нeбeca зaключивы,

“Oh, glorious Elijah!/Elijah great prophet,/earthly angel, heavenly man,/On earth the flesh you resurrected,/To heaven you flew,/Oh, glorious Elijah!/Elijah great prophet,/You blessed Elisha,/established him as a prophet,/and closed the sky,”12

Бoжe мили, чyдa нeвидeнa!/У Пaвлoвy cвeтoмъ мaнacтиpy/Пocтaвлeны oдъ злaтa cтoлoви,/Cви cy cвeци peдoмъ пoceдaли:/Ha вpxъ coвpe Гpoмoвникъ Илия,

“Dear God, unseen miracle!/At the monastery of St. Paul/Settled at golden tables,/all the saints are sitting around:/At the head of the table is seated Elijah the thunder-bearer,”13

Бoжe мили! чyдa вeликoгa!/Глeдax чyдa пpиje нeвиђeнa./У Пaвлoвy cвeтoм нaмacтиpy/Пocтaвљeни oд злaтa cтoлoви,/Cви ce cвeци peдoм пocaдили;/Haвpx coφpe Гpoмoвник Илиja,

“Dear God! Great miracle!/Have been seen miracles unseen before./At the monastery of St. Paul/Settled at golden tables,/all the saints are sitting around:/At the head of the table is seated Elijah the thunder-bearer,”14

Kaдa cвeци блaгo пoд‘jeлишe:/Пeтap yзe винцe и шeницy,/И кљyчeвe oд нeбecкoг цapcтвa;/A Илиja мyњe и гpoмoвe;

“When the saints distributed the gifts:/Peter took the vines and the shed, and the keys of the heavenly kingdom;/And Elijah the lightning and the thunder;”15

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | http://www.marquette.edu/maqom/pseudepigrapha.html (accessed on 9 August 2024). |

| 2 | Cor 12.1–5: It is not expedient for me doubtless to glory. I will come to visions and revelations of the Lord. I knew a man in Christ above fourteen years ago, (whether in body, I cannot tell; or whether out of the body, I cannot tell: God knoweth;) such an one caught up to the third heaven. And I knew such a man, (whether in body, or out of the body, I cannot tell: God knoweth;) how that he was caught up into Paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter. Of such an one will I glory: yet of myself I will not glory, but in mine infirmities. |

| 3 | Respondit Michael et dixit: Audite Michaelo loquente. Ego sum qui consisto in conspectu dei omne ora. Viuit dominus in cuius consisto conspectu quia non intermito uno die uel nocte orans indeficienter pro ienere umano. Et ego quidem oro pro eis qui sunt super terram. Ipsi autem non cessant facientes iniquitatem et fornicationes et non adferunt mihi in bono constituti in terris. Et uos contempsistis tempus in uanitate in quo debuistis penitere. Ego autem oraui semper sicut et nunc deprecor ut mittat deus ros et pluuia destinetur super terram. Etiam peto quousque et terra producat fructos suos. (Silverstein and Hilhorst 1997, p. 158). |

| 4 | Translation of the author of the Latin version L1: Ego sum Elyas qui horaui et propter uerbum meum non pluit cęlum annis tribus et mensibus vi propter iniusticias hominum. Iustus deus et uerax, qui facit uoluntatem famulorum suorum. Sepe etenim angeli deprecati sunt dominum propter pluuiam et dixit: Pacienter agite quoadusque seruus meus Elyas horet et precetur propter hoc et ego mitam pluuiam super terram. (Silverstein and Hilhorst 1997, p. 167; cf. Tischendorf 1866, p. 553). |

| 5 | Translation by the author. |

| 6 | See Note 5. |

| 7 | “Great Monthly Readings”, a collection of biblical books with commentaries and prologues, translated and original Russian lives of saints, and works by “church fathers” and Russian ecclesiastical writers, which was compiled during the 1530s and 1540s under the direction of Metropolitan Makarij of Moscow. |

| 8 | See Note 5. |

| 9 | Collection of information on the lives of the saints, arranged according to the days of the month. |

| 10 | See Note 5. |

| 11 | See Note 5. |

| 12 | See Note 5. |

| 13 | See Note 5. |

| 14 | See Note 5. |

| 15 | See Note 5. |

References

- Angelov, Bonyu St., Kuio M. Kuev, and Khristo Kodov. 1970. Kliment Okhridski, Săbrani săčinenija 1. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, pp. 673–706. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Pedrosa, Juan Antonio. 2021. Sources of Slavic Pre-Christian Religion. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Baun, Jane. 2007. Tales from Another Byzantium. Celestial Journey and Local Community in the Medieval Greek Apocrypha. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bessonov, Pavel’ A. 1861–1863. Kaleki perekhožie. Sbornik stikhov i issledovanie I–II. Moskva: Tipografija Vakhmetev. [Google Scholar]

- Hazzard Cross, Samuel, and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor. 1953. The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text. Cambridge: Mediaeval Academy of America. [Google Scholar]

- Istrin, Vasilij. 1897. Otkrovenie Mefodija Patarskogo i apokrifičeskie videnija Daniila v vizantiĭskoĭ i slavjanorusskoĭ literaturakh. Issledovanija i teksty. Moskva: Universitetskaja Tipografija. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Jordan E. 1903. Kul’t Peruna u južnykh Slavjan. Izvestija Otdelenija russkogo jazyka i slovesnosti Imperatorskoj Akademii Nauk 8: 140–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav V., and Vladimir N. Toporov. 1974. Issledovanija v oblasti slavjanskikh drevnostej. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Jacimirskij, Aleksandr I. 1915. Apokrify i legendy. K istorii apokrifov, legend i ložnykh motiv v južnoslavjanskoj pis’mennosti. Vyp. I–III. Petrograd: Imperatorskaja Akademija Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague R. 1983. The Apocryphal New Testament. Being the Apocryphal Gospels, Acts, Epistles, and Apocalypses. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 525–55, 563–64. First published 1924. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague R. 2004. Apocrypha Anecdota: A Collection of Thirteen Apocryphal Books and Fragments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 109–26. First published 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Karadžić, Vuk St. 1895. Srpske narodne pjesme. Knjiga druga. U kojoj su pjesme junačke najstarije. Belgrade: Štamparija Kraljevine Srbije. First published 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Karskij, Evtimij F., ed. 1962. Lavrent’evskaja letopis’ i suzdal’skaja letopis po akademičeskomu spisku. In Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisej. Leningrad and Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Vostočnoj Literatury, vol. 1. First published 1926–1927. [Google Scholar]

- Lajoye, Patrice. 2015. Perun, dieu slave de l’orage et ses successeurs chrétiens Elie et Georges. Archéologie, histoire, ethnologie. Paris: Lingva. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov, Pëtr A. 1901. Pokhvala Il’e proroku: Novoe slovo Klimenta Slovenskogo. Izvestija Otdelenija russkogo jazyka i slovesnosti Imperatorskoj Akademii Nauk 6: 236–80. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczyński, Michał. 2011. Kognitywna definicja Peruna: Etnolingwistyczna próba rekonstrukcji fragmentu słowiańskiego tradycyjnego mitologicznego obrazu świata. Studia Mythologica Slavica 14: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mil’kov, Vladimir V. 1999. Drevnerusskie apokrify. St. Petersburg: Iz-vo RHGU. [Google Scholar]

- Roždestvenskaja, Maria D. 1987. Apokrify o Il’e proroke. In Slovar’ knižnikov i knižnosti Drevnej Rusi (XI—Pervaja polovina XIV v.). Edited by Dmitri S. Likhačëv. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Theodore, and Anthony Hilhorst. 1997. Apocalypse of Paul. A New Critical Edition of Three Long Latin Versions. Geneva: Patrick Cramer Éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Sorlin, Irène. 1961. Les traités de Byzance avec la Russie au Xe siècle (I). Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétique 2: 323–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonravov, Nikolai S. 1970. Pamjatniki otrečennoj russkoj literatury II. Moskva: [The Hague—Paris: Mouton], pp. 22–30, 40–58. First published 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Tischendorf, Constantine von. 1866. Apocalypses Apocryphae: Mosis, Esdrae, Pauli, Iohannis, Item Mariae Dormitio. Lipsiae: Hermann Mendelssohn, pp. 34–69. [Google Scholar]

- Uspenskij, Boris A. 1982. Filologičeskie razyskanija v oblasti slavjanskikh drevnostej. Moskva: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Velikie Minei-Četii. 1945. Velikie Minei-Četii, sobrannye vserossiiskim mitropolitom Makariem. issues 1–14. St. Petersburg: Arkheografičeskaja kommissija, Istoriia russkoi literatury, vol. 2, part 1. Moscow and Leningrad: Akademija Nauk SSSR. First published 1868–1917. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos Marinas, E. Prophet Elijah as a Weather God in Church Slavonic Apocryphal Works. Religions 2024, 15, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080996

Santos Marinas E. Prophet Elijah as a Weather God in Church Slavonic Apocryphal Works. Religions. 2024; 15(8):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080996

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos Marinas, Enrique. 2024. "Prophet Elijah as a Weather God in Church Slavonic Apocryphal Works" Religions 15, no. 8: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080996

APA StyleSantos Marinas, E. (2024). Prophet Elijah as a Weather God in Church Slavonic Apocryphal Works. Religions, 15(8), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080996