I would like to identify three trends within digitalization that seem to challenge the traditional (neo)-Kantian deontological framework. They relate to the underlying understanding of humans as ‘rational agents’, technological objects and nature as mere ‘passive entities’, and societies as the place of ‘rational deliberation’.

In the next section, I will look at these three challenges in turn. Since they cover a broad range of domains, I want to limit myself to the case of a specific type of digital technologies, namely ICT-based behavior change technologies, as mentioned above. BCTs are technologies that are intentionally designed to change the behavior of users. Digital BCT seem to perfectly illustrate the changes in digital objects, subjects and intersubjectivity as they affect all three domains. Furthermore, these technologies are already in existence and are in fact getting more and more widespread. Other, more advanced technologies that would alter the three domains even more radical—such as fully autonomous robots or full-fledged AI—are still more distant and futuristic. They will therefore be left out of the scope of this essay. Digital BCTs can serve as ‘transition’ technologies that illustrate the trend towards fully autonomous AI. The real effects of BCTs can already be observed and can therefore inform ethical analysis.

3.1. Deontology and Digital Objects

One can argue, that it was fair enough in the time of the Enlightenment to focus on human agency only, and regard objects as passive things that do not have agency of themselves. However, recently we observe that the distinction between subjects and objects seems to get blurred for technological artefacts with the rise of digitalization. Algorithms take over human decisions, they help to fly planes, invest in the stock market and will soon let cars drive autonomously. The potential end-point of this development might be robots that pass the Turing test [

12], are equipped with full-fledged artificial intelligence and can for all intense and purposes be regarded as real actors. This will raise questions, whether these robots should be regard as ‘persons’ and which—if any—of the human rights should be applied to them [

13,

14,

15].

The observation that technologies are more than mere neutral tools is however older and pre-dates the focus on digitalization. Already Winner famously claimed that artifacts—such as bridges—can have politics [

16]. Actor-network-theory goes even further and argued that we should ascribe agency and intentionality to all artifacts and even to entities in nature, such as plants [

17,

18,

19]. In a similar vein, post-phenomenology has been developed in part as a strict opposition to the Cartesian subject-object dualism and maintains that all technologies affect human agency, since they shape human perception and alter human action [

11,

20]. One can of course still argue that it is meaningful to distinguish between full-fledged human agency and intentionality on the one hand, and whatever ‘objects’ are currently doing on the other hand [

21,

22]. However, the phenomenon of increasing agency of objects through digitalization deserves attention, especially for an ethical approach such as deontology that starts from notions of (human) agency and autonomy.

For the purpose of this paper, I therefore want to suggest to distinguish between three types of objects: “good old objects”, “digital objects” and “autonomous objects”. The intuitive distinction behind these three categories is the amount of agency we are willing to ascribe to any of these objects: no agency (good old objects), some limited form of agency (digital objects), and full-fledged agency (autonomous robots) (This distinction is thus meant to be conceptual and therefore independent from any concrete framework about agency of artifacts. Depending on your preferred philosophy of technology, you can judge what concrete objects belong in each category. E.g., mediation theory and actor-network theory might claim that “good old objects” never really existed, this class would thus be an empty class under this framework. On the other extreme, if you are embracing a framework that requires mind and consciousness as necessary pre-conditions for full-fledged agency, you might doubt whether there ever will be (fully) autonomous objects (see, e.g., Searle’s criticism of the extended mind). For a conceptual analysis of the relation between agency and artifacts see [

23,

24]).

Traditional tools (without any agency) are what I want to refer to for now as “good old” objects. A screwdriver, that it used by a mechanic might have affordances [

23], but lacks agency of its own. It does nothing in the absence of a human being, other than just lying there in a toolbox. Next to this we have at the other end of the spectrum “fully autonomous robots”, that for all intense and purposes “act by themselves” and whose actions might at some point be indistinguishable from what a human would do. These are the robots that will pass the Turing tests and whose actions can no longer be distinguished sharply from those of a human being. In between, we have a third category consisting of all technologies that encompass some form of agency. There are currently many artifacts to which we would ascribe some form of agency. Self-driving cars, e.g., can be seen to decide autonomously how to drive on a highway, but of course they lack many other aspects of agency. However, this in-between category does not seem to fit into the traditional subject–object dualism. It does thus require special consideration from a deontological standpoint. Let us look at all three categories from a deontological perspective.

How would Kant treat ‘autonomous objects’? As said above, traditional Kantian ethics merely distinguishes between subjects and objects. Subjects are agents that are capable to act autonomously based on what they have most reasons to do (and who can reflect on this capacity and give reasons for their actions). Mere objects do not have this capacity. In this Cartesian spirit, Kant also famously assumes that animals belong into the category of objects. They are no moral agents, and they have no intrinsic moral status [

25,

26].

However, the first thing to note is, that there is nothing in the Kantian enterprise that restricts moral agency to humans only. Kant himself speculates about potential rational agents that might exist on other planets and that might be sufficiently similar to humans: they could possess a free will, in which case—according to Kant—also their actions would be subject to the same moral law. According to Kant the moral law even binds the agency of God. Kant is thus not a ‘speciecist’ in the terminology adapted by Singer [

27]. It is not our biology that makes us special, but our capacity to act morally. We can therefore speculate that once artificial agents encompass autonomous agency, that is sufficiently similar to human agency, they should be seen as bound by the same moral law as humans. At least that would be a natural application of Kant’s theory to autonomous artificial agents. In short, if artificial agents ever become ‘subjects’, they are bound by the same moral law that all rational and free agents are subjected to, according to a Kantian framework. Fully autonomous AI agents, would therefore need to be treated like ‘subjects’. Or in other words: if artifacts (technological objects) ever possess the necessary and sufficient conditions for free and autonomous moral agency, then they should be treated as ‘subjects’, i.e., as persons. (This question is independent from the issue of whether the Kantian framework is the best framework to implement in artificial moral agents [

28,

29,

30], or whether it might even be immoral to try to create Kantian artificial moral agents in the first place. The later point has been argued by Tonkens, based on the assumption, that artificial moral agents could not have free will [

31]. For a general analysis of ‘moral agency’ of artificial agents see [

32,

33].)

Kant also has no problem to deal with mere good old objects. Objects can be used as tools and—in a Kantian framework—there are no duties that we owe to objects, except in cases where our actions would violate the rights of other humans. We can destroy our property and, e.g., disassemble our old cars and sell the pieces we no longer need. We do not owe anything to mere objects, at least not in the Kantian framework. It is, therefore, precisely the “in-between category” that raises interesting questions. I will thus focus on the case of distributed agency, and I will illustrate a deontological perspective by analyzing the case of behavior change technologies.

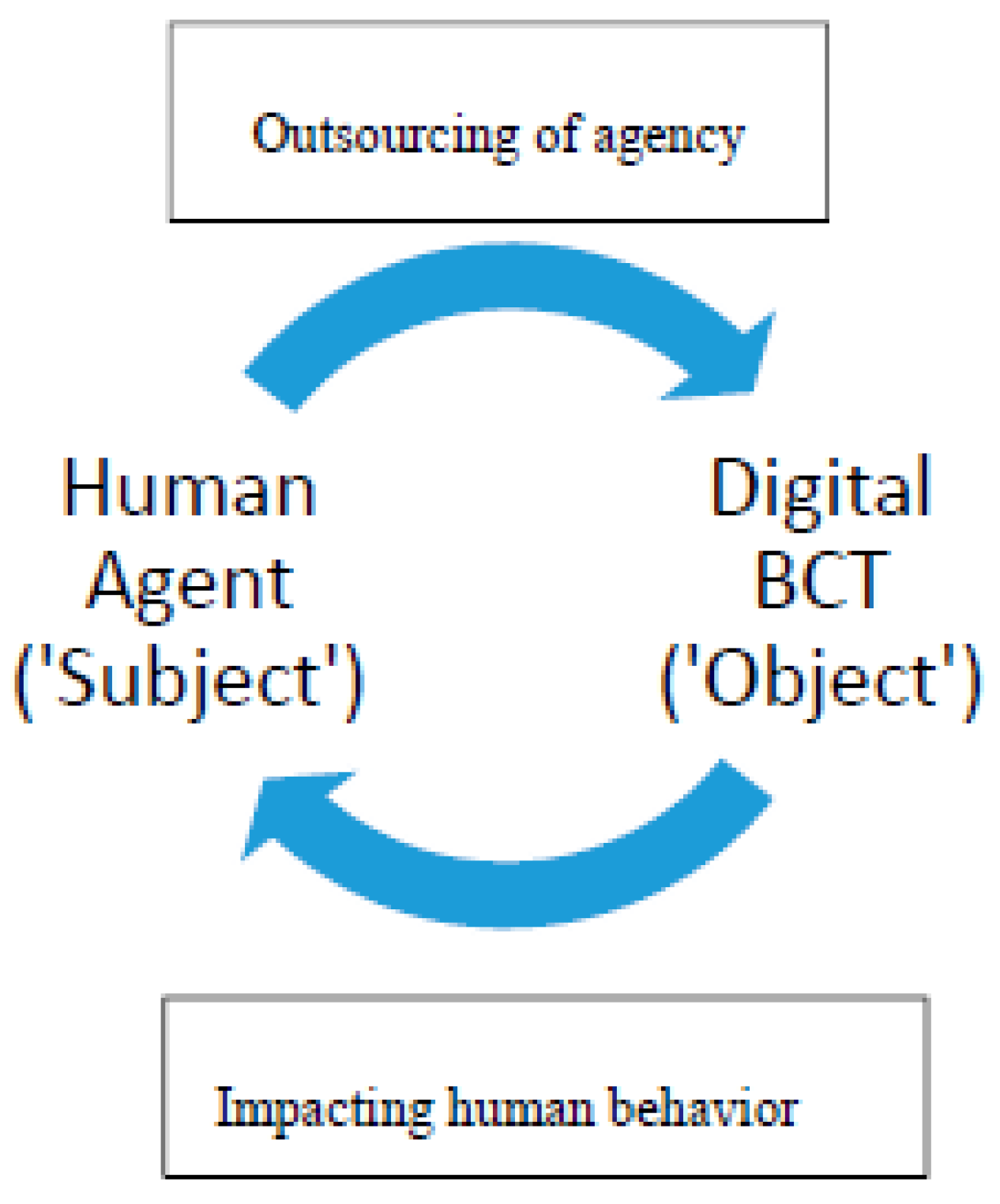

Digital behavior change technologies affect human agency, but also start to inter-act with humans, even if currently only in limited forms. Conceptually, I want to therefore distinguish between two cases of the ‘flow of agency’ in digital BCTs (see

Figure 1). (1) One the one hand, BCTs can be used to affect the behavior of users. They are designed to change the attitude and/or behavior of users. In this case the traditional human subject is not the source, but the target of the influence, and the digital BCT acts with the intent to influence human agency. Users might or might not be aware of these influences. I will focus on this category first.

(2) On the other hand, BCTs can be used by humans to enhance or extend their agency. For example, I can use a health-coaching app to help me reach my goals and support my desire to exercise more. In this case I am delegating or expanding my agency; the human subject is so to speak the source of the agency. I will look at this category in the next paragraph (on ‘digital subjects’), since these are cases of agency that are initiated by the subject.

It must be noted that this distinction is a conceptual one: the same technology can exercise both forms of agency. An E-coaching health app is in part an extension of human agency (as it is installed and initiated by the user), that—once installed—goes on to act upon the user (e.g., in pushing against weakness of the will). It does thus encompass both flows of agency: from user to technology and from technology to user. Since both cases raise different ethical issues it is nevertheless helpful to distinguish these two dimensions analytically and treat them separately.

Let us look more closely at the way in which digital BCTs affect human agency. Already Fogg observed that Computers and ICT technologies can be used to steer human behavior. He defined persuasive technologies as those technologies that were intentionally designed to change human attitudes and/or behavior [

34]. Persuasive technologies were originally studied under the header of ‘captology’, referring to ‘computers as persuasive technologies’. The advent of digitalization allowed first computers and later smart technologies to monitor user behavior via sensors and to try to actively influence user behavior. Designers of BCT started to use psychological research to steer users towards desired behavior [

35,

36,

37].

Recently, Hung [

38] has distinguished two classes of behavior change technologies: material BCT (‘nudges’) and informational BCT (‘persuasive technologies’). Material behavior change technologies change the physical material environment in which users make decisions. One example would be a speed-bump that makes car-drivers slow down. Informational BCTs use feedback and information to guide or influence user behavior. A car-dashboard can, e.g., display a red color if the driver is wasting energy or reward him with symbolic digital flowers that grow on the dashboard if he keeps on driving in an environmentally friendly way. Informational BCTs are the most interesting type from a digitalization perspective, as they use ICT to monitor behavior and digital user interfaces to give evaluative feedback.

If one looks at informational BCT from a Kantian perspective one can develop ethical guidelines for the design of these technologies. A first deontological principles for BCT can be derived from the importance of autonomy and rationality within Kantian ethics. First of all, informational BCT are digital objects whose agency targets to influence human agency. Since autonomy is a key value in the Kantian framework, we can argue that informational BCT should be compatible with user autonomy. This means more specifically that they should allow for voluntary behavior change that is compatible with acting in accordance to what you have most reasons to do [

39,

40].

This means that, other things being equal, a non-coercive intervention should be preferred in the design of BCT. Smids [

40] has elaborated in more detail, what the requirement of compatibility with free and rational behavior change would entail for the design of these so called ‘persuasive’ technologies. He defines BCTs as coercive, that do not allow for a reflection on the reasons for behavior change, such as mandatory speed limiting technologies. A BCT that gives a warning, if one exceeds the speed limit, is compatible with rational behavior change. In principle the user can override these persuasive technologies. Thaler and Sunstein [

41] also try to accommodate this requirement in their advocacy for ‘nudges’, since these should be compatible with the free will of the users. They define nudges as holding the middle between paternalism and libertarianism. Nudges push users in a desired direction, but do not coerce them to change their behavior. (The question whether ‘nudges’ are, however, really compatible with autonomy is debated extensively in the literature [

3,

42]).

A second guideline can be related to the observation that digital persuasive technologies are going beyond being mere objects. Informational BCT establish a (proto-)communicative relation with the user: they give feedback on behavior, warn or instruct users to behave in a certain way and give praise for desired behavior. I have argued earlier that this establishes a primitive type of a basic communication [

43,

44]. Therefore, we cannot only treat these BCT as mere ‘objects’, but we can apply basic ethical rules that have prior only been useful in the relation between humans. The validity claims of communication, that have been analyzed by Habermas [

10] and discourse ethics scholars, can be applied to the relation between persuasive technologies and humans. Like in the human–human case, the feedback that persuasive technologies give should be comprehensible, true, authentic and appropriate.

Since informational BCTs often use feedback that should not require much cognitive load from the user, there is always a risk that the feedback is misinterpreted. Designers should therefore use easy to understand feedback, like, e.g., a red light for a warning and a green light for a positive feedback. The feedback should obviously be true, which might be more difficult in the case of evaluative feedback. Toyota hybrid cars, e.g., give us feedback ‘excellent’ written on the car dashboard, if the user drives in a fuel-efficient way. However, only the factual feedback of gallons per liter is accurate and properly truthful. The challenge of evaluative feedback is, who gets to decide what counts as ‘excellent’, and is the evaluation transparent to the user? Authenticity refers to the obligations of designers to not mislead users and give ‘honest’ feedback. Appropriateness refers to finding the sweet spot between too much insistence in attempting to change behavior vs. giving up to early (see [

5] for a more detailed analysis of these four validity claims, for a critical view see [

45]). It is plausible to assume, that future informational BCTs will be even closer in their behavior to human feedback, it is therefore important to reflect on the implications of this trend for their ethical design [

37].

To summarize the analysis of BCT as digital objects, one can formulate the main principle of deontological ethics as follows. The design of digital technologies should be compatible with the autonomy and the exercise of rational choice of the user. The preferred method of behavior change of informational BCT should be in line with basic truth and validity claims of human–human interaction. This means that persuasion should be preferred over coercion or other methods of behavior steering. Digital BCTs should be in line with ethical behavior we would expect other humans (subjects) to display. The latter is particularly true the more the digital BCTs move towards increasing (autonomous) agency. From deontology the main guiding principle for digital objects is therefore, that the usage and design of such technologies should be compatible with the conditions for human moral agency and the human capacity to act based upon what they have most reason to do. In short, digital objects should not undermine what makes Kantian ‘subjects’ rational agents in the first place. Digital BCT should thus respect the requirements of epistemic rationality: human agents should be able to base their actions as much as possible on a reflection on what they have most reasons to do.

3.2. Deontology and Digital Subjects

We have seen above that digitalization adds agency to our technological objects. In this section I want to look at the changes in the age of digitalization from the perspective of the acting subjects. As argued above, the focus of this section will thus be on the flow of agency from human subjects to digital objects. Like before, we can make a similar typology to distinguish different types of (the understanding of) ‘subjects’. In the age of Kant, human subjects were seen to be the only known examples of free and autonomous agents. In so far as this category still makes sense today, we can call these the “good old subjects”. Whereas the envisioned end point of digital objects are fully autonomous, possibly conscious acting robots, the vision we find with regard to future of human ‘subjects’ is the idea of a merging of humans and AI to create transhuman agents that have incorporated AI as part of their biology [

46,

47]. Transhuman cyborgs are thus the second category. In between we find theories of extended agency, which I would like to call ‘digital subjects’. We have observed above that objects get degrees of agencies of their own. We can similarly observe the extension of the human mind beyond the borders of the biological body with the help of digital technologies. Whereas digital objects are designed to affect human agency, digital subjects are cases of distributed agency, starting from the intentions and choices of the human subject.

Within philosophy of technology theories of the extended mind [

48,

49] and the extended will Ref. [

50] have been developed to account for the fact that humans can outsource elements of their cognitive functions of their minds or their volition with the help of technological artifacts (The idea that tools are an extension of human agency or the ‘mind’ is older than the rise of digital technologies (cfr. [

51]). Already a pen and paper, or a notebook can be seen as extensions of the human mind. For an application of theories of extended cognition to digital technologies see: Ref. [

52].). Again, it is this middle-category that is most interesting from a Kantian perspective. BCTs can not only be used to affect the agency of others, but also as an outsourcing of will-power. If we apply a deontological perspective to these technologies, we can develop prima facie guidelines for their design from a Kantian perspective.

In the previous section, we have formulated negative guidelines, about what BCTs should not do. We were starting from the Kantian worry to protect human autonomy and agency from improper interference from digital objects. Can we complement these guidelines with some positive accounts starting from the agency of digital subjects? We might regard these negative requirements (not to undermine or interfere with human autonomy) as perfect duties in the Kantian sense. Are there also weaker principles, or “imperfect duties”, i.e., guidelines that might point towards BCTs that could be regarded as morally praiseworthy?

I indeed suggest to consider two additional guidelines, which are weaker than the ones suggested above. As a positive principle one could add that BCT should, if possible, encourage reflection and the exercise of autonomous agency in the user. Designers should at least consider, that sometimes the best way to change behavior in a moral way is to simply prompt the user to actively reflect and make a conscious and autonomous choice. A smart watch for health-coaching for example might prompt the user to reflect on past performances and ask him to actively set new goals (e.g., the amount of calories to be burnt or minutes of exercise for the next week). Health apps can display supporting reasons for eating choices, to try to convince—rather than persuade—the user to change his diet. Bozdag and Hoven [

53] have analyzed many examples of digital technologies that help users to overcome one sided information on the internet, and that can help to identify and overcome filter-bubbles. One example they discuss is the browser tool ‘Balancer’ that tracks the user’s reading behavior to raise awareness on possible biases and to try to nudge the user to make her reading behavior more balanced.

If we take the observations of the prior section and this section together, we can use the epistemic requirement of deontology to distinguish three different types of digital behavior interventions in BCT based on their relation towards human autonomy and the human capacity to base choices on rational deliberation. (i) Some BCTs might be incompatible with the exercise of autonomous deliberation (e.g., coercive technologies), (ii) others might be compatible with it (persuasive technologies), (iii) some BTCs might even actively encourage or foster reflection (deliberative persuasive technologies).

There is a second deontological principle, that could be regarded as an imperfect duty in the design of digital BCTs. Behavior change technologies can be designed to support users in cases of weakness of the will. They can remind us, that we wanted to exercise, watch out for filter-bubbles, or that we planned to take our medication. This outsourcing of will-power to digital technologies is not problematic as such, and can even be seen as empowering, or as a “boosting” of self-control [

54]. The worry, one might have, however, with these technologies is the problem of deskilling of moral decision making through technology [

55]. Rather than training will-power or discipline, we might become dependent on technologies to reach our goals, while at the same time loosing capacities of will-power and relying on the fact that BCTs will and should tell us what to do.

In Ref. [

5] I have, therefore, contrasted ‘manipulation’ with ‘education’ as paradigmatic strategies of behavior change. Both are asymmetrical relations, that intend to change behavior; but they use opposite methods. The aim of manipulation is to keep the asymmetrical relation alive and keep the user dependent. Manipulation is therefore often capacity destructive. Education on the other hand aims at overcoming the initial asymmetrical relation between educator and user, it aims at capacity building. This strategy might therefore also better be referred to as ‘empowerment’. Designers of BCTs can thus try to use the paradigm of educational intervention in the design of BCT and reflect on the question, whether their technologies built up (rather than destroy) individual capacities, such as, e.g., digital E-coaches that aim at training and establishing new habits. One could thus with some oversimplification formulate as a deontological guiding principle, that ideally the aim of the persuasion in BCTs should be the end of the persuasion.

These positive guidelines bring us, however, to a controversial point of a Kantian deontological approach. We have identified motivational rationalism above as a key-feature of Kant’s deontology: the requirement that moral actions should not only be in-line with the action that an agent has most reasons to pursue, it should also (at least in part) be motivated by these reasons. I would argue, in line with many (early) criticisms of Kant, that this requirement is too strict. (Already, Kant himself seems to take back some of the rigor of the motivational requirements in his Groundwork, by including an elaborated virtue ethics in his Metaphysics of Morals). A convincing re-actualization of Kant should let go of the strict motivational requirement and replace it with a weaker version. Rather than always being motivated by reason, it is enough that a user is in principle able to give reasons that support his choice of action, though these reasons must not play a motivational effect at all times of the action.

A weaker version of the motivational requirement would allow for two things with regard to digital BCTs. It would encourage the development of BCT that are meant to overcome weakness of the will, by supporting users in their tasks as discussed above. The weak requirement would, however, still require, that the lack of “autonomy” within the behavior change interference could (or maybe even should) in principle be complimented by an act of rational agency, motivated by reason, at some other point in time. The best way to guarantee this, is to call for an actual act of decision that is based on reasoning. This could, e.g., be a free and autonomous choice to use a given BCT in the first place, with the intention of overcoming temptations or weakness of the will. It would not need to imply that the BCT itself only appeals to reflection and deliberation in its attempts to change the user behavior.

3.3. Deontology and Digital Societies

So far, we have focused on the domains of digital subjects and digital objects, and suggested to re-interpret the epistemic and motivational requirements of Kantian deontology to develop guidelines for the design and usage of digital BCTs. For the sake of completion, I want to conclude with a few remarks on the remaining, third aspect: digital intersubjectivity and the requirement of rational social deliberation. This topic deserves a more detailed analysis than can be given here in the context of the paper. There is a rich, growing literature on the impact of social media on societal debates and opinion forming [

56,

57,

58], though not many of these analyses are taking an explicitly deontological perspective. For the reminder of the paper I will restrict myself to try to identify the three most pressing challenges from a deontological perspective.

Initially social media have been greeted as a pro-democratic technology (e.g., due to their role in the Arab spring [

59,

60,

61,

62] or due to their potential to let more people participate in the public debate [

63]. However, recent worries have emerged about the impact of fake news on Facebook and twitter and the attempt to use these technologies to influence public debates and to interfere with elections [

64,

65]. These technologies are again aiming at behavior change: they can be used to change voter behavior and can target the attitudes and beliefs that people hold.

The first most fundamental worry from a deontological perspective is linked to the requirement of societal deliberational rationalism and its importance for the public sphere. Any deontological theory of social institutes will stress the importance of communicative rationality [

66] for public decision making, including debates in the public sphere. The spread of social media technologies can then be seen pessimistically as counter-enlightenment technologies that threaten to replace communicative rationality with strategic rationality and place humans again under a self-imposed tutelage (to use Kant’s language). Whereas deliberation is a conscious and transparent process to debate public issues, fake-news, misleading ads and attempts to polarize the debate can be regarded as attempts to use strategic rationality. A ‘silent might’ (Christian Illies) that threatens to distorts rational debates. This is particularly true with regard to two recent trends. The first is the distortion between “truth” and fake-news. Some researchers worry that we are moving towards a post-truth age [

67], in which it will be more and more difficult to distinguish facts from fictions, as traditional news-media (with editorial authority) are declining and social media—fueled by a click-bait attention economy—take over. Twitter, e.g., is not a medium that lends itself to a carefully considered debate, due to the character restrictions [

64], but it is a great medium to post short oversimplifications.

The fact that humans are willing to engage more, if they disagree with each other, leads to a polarization of the debate, where the loud voices are heard and the moderate voices seem to be less visible. This is helped by filter bubbles or echo-chambers, in which users are only confronted with their own views and not challenged to engage with view point diversity [

68]. The change in current political trends towards a rise of populism on the left and the right side of the political spectrum, together with a decline of traditionally more moderate parties, has many different reasons. The change of the shape of the public sphere due to social media may very well be one of the contributing factors [

64].

What should we make of these trends from a deontological perspective? I would argue, that traditional deontological theories about the importance of rational deliberation for a healthy society can give guidelines, that are, however, abstract, unless they are spelled out in more details in careful future analysis. For now, I would suggest to keep these three guidelines in mind in the development and usage of social media.

The first guideline would be to design social media technologies in line with the requirements of communicative rationality, and limit the aspects of strategic rationality [

5,

53,

66]. One example would be the debate about hate-speech on twitter. In an interesting pod-cast debate, Jack Dorsey (CEO of Twitter) discusses various attempts to deal with hate-speech on the platform [

69]. The debate covers the two ends of the spectrum. On the one hand, twitter needs to establish guidelines about which speech acts should be forbidden and lead to a ban from the platform. On the other hand, twitter could consider formulating also a positive ideal about the type of communication that it would like to encourage on its platform. Some of these aspects can be implemented differently in the technology design: hate-speech could be filtered out by humans, by algorithms or brought to a deliberative panel of voluntary users, that decide on possible sanctions. But twitter could also seek technological solutions. Twitter could implement, e.g., an ‘anger-detection’ algorithm, that prompts the user to save a harsh tweet before publishing it and ask the user to re-consider the usage of aggressive language before posting it. In a similar vein, Instagram has recently tried to improve focus on content and remove incentives for strategic behavior by hiding the amount of likes a picture gets. In the wake of the coronavirus, Twitter in the Netherlands, displayed a prominent link to official information by the Dutch Ministry to counter false information and rumors. These can be seen as attempts to (re-)design social media in light of the requirements of communicative rationality.

Future research should spell out in more detail what the application of communicative rationality would mean for the design of social media and BCT. Since the aim of deliberation is the joint search for the truth, technologies could try to overcome echo-chambers by occasionally presenting users with popular view points from an opposing position, rather than adding suggestions that confirm existing beliefs. The debate on whether tech-companies like Facebook or Twitter should be regarded also as media-outlets, that have a responsibility to not promote fake news, is currently very fierce in light of the upcoming US election. From a societal deliberational rationalism perspective, it would seem that these companies have indeed a greater editorial responsibility than they are currently willing to take.

These debates are being complicated by the fact, that—on the other hand—freedom of speech is an important value for communicative rationality and social deliberation as well. It is, therefore, important to develop a theory of communicative rationality in the age of social media, which investigates these questions more carefully than can be done in this short essay. This is arguably the most urgent field of research for the ethics of digitalization from a Kantian perspective.