Good Practices for Web-Based Cultural Heritage Information Management for Europeana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Project

- Content Contributors: As contributors, users have been using the platform to upload/edit and submit content and metadata. Effortless and mass-uploading of vast data sizes was implemented using Cloud technologies and techniques which do not impose data-entry delays while uploading, enabling parallel processing to be implemented. New contributors can join the consortium and enrich the thematic channel by submitting their content. This process is very important for new researchers who wish to store and make their research available, as they will be located centrally, ensuring that they preserve their content ownership rights.

- Content Validators: The platform’s users are themselves content experts and as such they can act as validators for the submitted content. However, our external data validation experts are on hand during and before the final submission of a collection. This feature, combined with the creation of well-typed term vocabularies, enables metadata accessibility and uniformity, creating a solid data structure that can be effectively accessed both manually and automatically.

- Developers: We have been dealing with data and metadata issues, enabling existing content to be described appropriately, while new content can also be described and classified. New content involves data types including augmented reality, virtual reality and holographic content, new audio types involving locative information and latest minimum content-sampling requirements that enable this content to be used for the development of virtual-reality and holographic presentation environments.

- Users: Users are able to view the digital collection items and now the exhibition with a complete timeline. Users are presented with the options to browse generally through the collection, search for specific terms, identify the copyright terms and trace the copyright owner should they wish to use the content within their projects. They may also propose edits and corrections to the database.

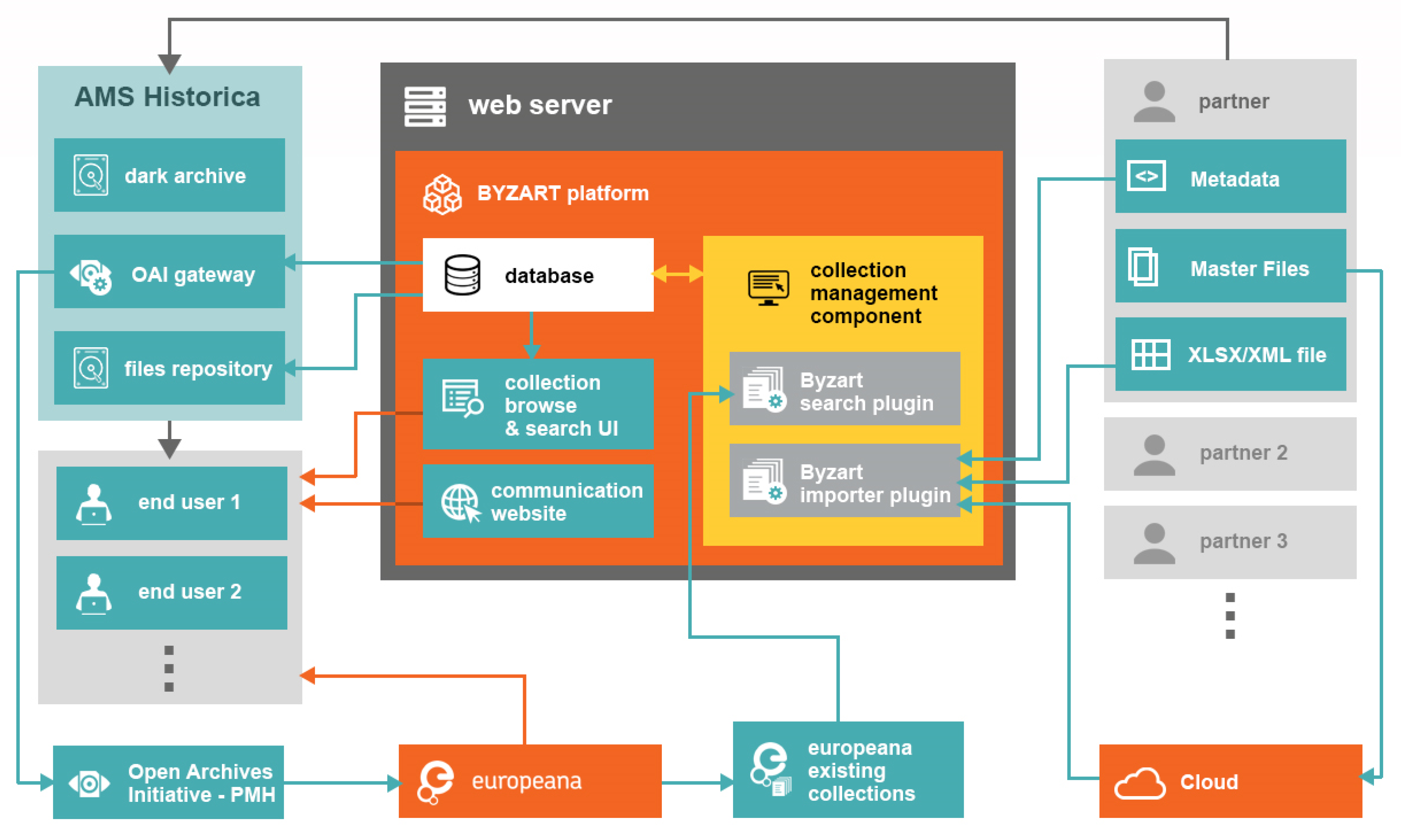

3. Technical Implementation

- The platform needed to be available online through a Web interface. Since the project involved multiple partner institutions from multiple countries, an online collaborative solution was an absolute necessity. The amount of work required by each institution dictated the use of multiple staff members. This meant that the requirement of specific software tools on the side of the content providers would hinder the project’s chances of success. Thus, a Web interface was deemed necessary, since that would mean that a browser and an active internet connection would be sufficient for someone to work on the project.

- The platform needed to be fast, reliable and secure. Online data management systems are often limited by performance issues caused either by network latency or lack of processing power [12]. The project’s scope meant that the platform had to be able to carry enough memory and processing power to run a big database server-side without causing delays, while at the same time providing a user interface that not only had low system requirements from each contributor’s device but also was fully compatible with a variety of operating systems and browsers. Additionally, none of these requirements could be fulfilled at the cost of data security. This meant that a secure, robust and fast hardware and software combination was necessary for the Web server.

- The platform needed to be able to handle large data and files. The project’s scope meant that the platform had to be able to work with vast data and metadata sizes on the server side, as dictated by the nature of the objects of cultural heritage that were its focus. Thousands of high-quality image, video and audio files had to be collected, organized and served, and for that reason, the use of Cloud services was employed.

- The platform needed to allow users to provide content in a non-serial manner. The sheer number of cultural heritage objects involved would have made the process of manual input a daunting task. For that purpose, it was deemed necessary for processes to be created that were used to batch-import both metadata and actual content files.

3.1. Building the Platform

3.2. Facilitating the Data Entry Process

3.3. Ensuring Adherence to Standards

3.4. Diffusion of the Collected Data

3.5. Enriching the Final Project

4. Implementation Importance and Future Uses

- The use of Cloud storage in order to facilitate the transmission of data between content providers and the system as well as maintain high-quality master files of the digitized items.

- The focus on facilitating the end user through means of batch metadata importing, using external formats such as xlsx or xml while simultaneously converting that information into a popular standardized data structure. This can be especially helpful for ingesting collections with existing digital information as long as the process focuses on preserving the richness of the original metadata [16].

- The definition of URI vocabularies and a system that allows the end user to provide information in text form that will be converted into URIs by the system as well as a system that validates user-provided URIs from specific sources.

- The focus on supporting already dominant dissemination technologies such as OAI-PMH and using internationally acknowledged standards like the EDM. This can help promote the content and ensure its longevity in the ever-changing World Wide Web. The promotion and focus on the diffusion of the digitized content should be considered an integral part of the digitization process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dimoulas, C.; Kalliris, G.; Chatzara, E.; Tsipas, N.; Papanikolaou, G. Audiovisual production, restoration-archiving and content management methods to preserve local tradition and folkloric heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, N.; Voorburg, R.; Cornelissen, R.; de Valk, S.; Meijers, E.; Isaac, A. Aggregation of linked data in the cultural heritage domain: A case study in the Europeana network. Information 2019, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagedorn-Saupe, M.; Peukert, A. Do It Yourself Digital Cultural Heritage: Three Services Developed by Europeana Space that Support the Creative Reuse of Digital Cultural Heritage Content. Uncommon Cult. 2018, 19, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Psomadaki, O.; Dimoulas, C.; Kalliris, G.; Paschalidis, G. Digital storytelling and audience engagement in cultural heritage management: A collaborative model based on the Digital City of Thessaloniki. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, M.; Davies, R. Towards a Holistic Documentation and Wider Use of Digital Cultural Heritage. In Metadata and Semantics Research, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, MTSR 2018, Limassol, Cyprus, 23–26 October 2018; Garoufallou, E., Sartori, F., Siatri, R., Zervas, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 76–88.

- Anagnostou, G.; Chatziefstratiou, A.; Peristeri, T.; Theofanellis, T. Suggestions on how to use Europeana for pedagogical purposes in order to promote Europe’s cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Cultural Informatics, Communication & Media Studies, Mytilene, Greece, 13–15 June 2019; Aegean University: Mytilene, Greece; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kabassi, K. Evaluating websites of museums: State of the art. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 24, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, A.; Haslhofer, B. Europeana linked open data—Data. Eur. Semant. Web 2013, 4, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroni, S.; Tomasi, F.; Vitali, F. The aggregation of heterogeneous metadata in Web-based cultural heritage collections. Int. J. Web Eng. Technol. 2013, 8, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deliyannis, I.; Giannakoulopoulos, A.; Poulimenou, F. Combining Byzantine Art Content and Interdisciplinary Technologies. In The Silk and the Blood. Images of Authority in Byzantine Art and Archaeology. Inauguration of the Digital Exhibition and Proceedings of the Final Meeting of “Byzart-Byzantine Art and Archaeology on Europeana” Project, Bologna, 15 February 2019; Baldini, Ι., Lamanna, C., Marsili, G., Orlandi, L.M., Eds.; Università di Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2019; pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomov, N.; Simeonov, B.; Parvanova, J.; Alexiev, V. Europeana creative. EDM endpoint. Custom views. Digit. Present. Preserv. Cult. Sci. Herit. 2013, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, C. The New Hardware Development Trend and the Challenges in Data Management and Analysis. Data Sci. Eng. 2018, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omeka Project. Available online: https://omeka.org/about/project/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Orlandi, L.M.; Marsili, G. Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage Preservation. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2019, 3, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Szekely, P.; Knoblock, C.A.; Yang, F.; Zhu, X.; Fink, E.E.; Allen, R.; Goodlander, G. Connecting the Smithsonian American Art Museum to the Linked Data Cloud. In The Semantic Web: Semantics and Big Data; 2013 ESWC 2013. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boer, V.; Wielemaker, J.; Gent, J.; Hildebrand, M.; Isaac, A.; Van Ossenbruggen, J.; Schreiber, G. Supporting Linked Data Production for Cultural Heritage Institutes: The Amsterdam Museum Case Study. The Semantic Web: Research and Applications 2012, ESWC 2012. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ionian Research Committee. 80418: Digital Tour Guide Making Use of Augmented Reality and Holograms. Available online: https://rc.ionio.gr/programs/80418/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Ionian Research Committee. 80351: BRENDA-Digital Gastronomy Routes. Available online: https://rc.ionio.gr/programs/80351/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Koukopoulos, Z.; Koukopoulos, D. Evaluating the Usability and the Personal and Social Acceptance of a Participatory Digital Platform for Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2019, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Plugin Name | Utility |

|---|---|

| ByzartBatch | Enabled the batch editing of item status concerning the QA process. |

| ByzartDocumentation | A series of documentation and user help pages in the Omeka administration area. |

| ByzartElements | Implemented EDM in the Omeka classic environment. |

| ByzartExporter | Used for exporting metadata in EDM xml format files |

| ByzartGalleries | Interface for creating multi-item themed galleries available to the public |

| ByzartImporter | Used for importing items from spreadsheets or xml files as well as content files from the Cloud |

| ByzartOutput | Used to implement the ability for Omeka to display the EDM schema in XML format online. |

| ByzartSearch | Interface for searching Europeana collections and seamlessly importing items to be displayed as external collection items. |

| ByzartStatistics | Interface for displaying statistics regarding the content provided by every partner |

| ByzartValidate | Implementing the validation of the EDM schema in Omeka’s content form. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannakoulopoulos, A.; Pergantis, M.; Poulimenou, S.M.; Deliyannis, I. Good Practices for Web-Based Cultural Heritage Information Management for Europeana. Information 2021, 12, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12050179

Giannakoulopoulos A, Pergantis M, Poulimenou SM, Deliyannis I. Good Practices for Web-Based Cultural Heritage Information Management for Europeana. Information. 2021; 12(5):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12050179

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannakoulopoulos, Andreas, Minas Pergantis, Sofia Maria Poulimenou, and Ioannis Deliyannis. 2021. "Good Practices for Web-Based Cultural Heritage Information Management for Europeana" Information 12, no. 5: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12050179

APA StyleGiannakoulopoulos, A., Pergantis, M., Poulimenou, S. M., & Deliyannis, I. (2021). Good Practices for Web-Based Cultural Heritage Information Management for Europeana. Information, 12(5), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12050179