Social Networks and Digital Influencers in the Online Purchasing Decision Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Digital Influencers and the Digital World

2.2. Internet, Purchase Process, and Digital Influencers

3. Materials and Methods

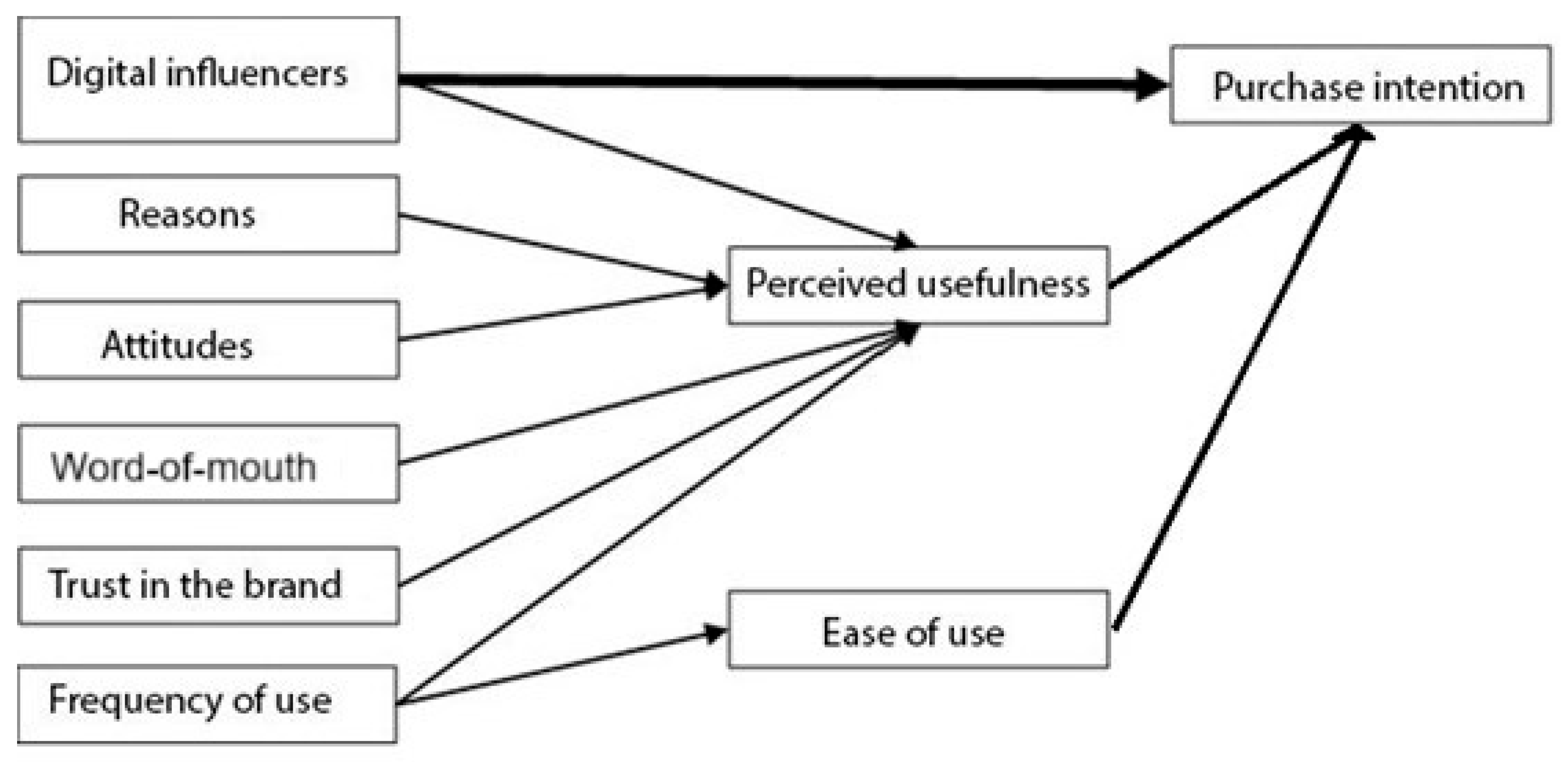

3.1. Problem, Objectives, and Conceptual Model

- -

- To check whether social networks and digital influencers have an influence on consumers in the process of deciding to buy products online;

- -

- To check whether sociodemographic factors influence social network users in the online product purchase decision process;

- -

- To identify consumers’ perceptions of the content posted by digital influencers.

3.2. Methodology, Research Framework, and Conceptual Model

3.3. Instrument and Procedures for Collecting and Analyzing Data and Validation of Empirical Model

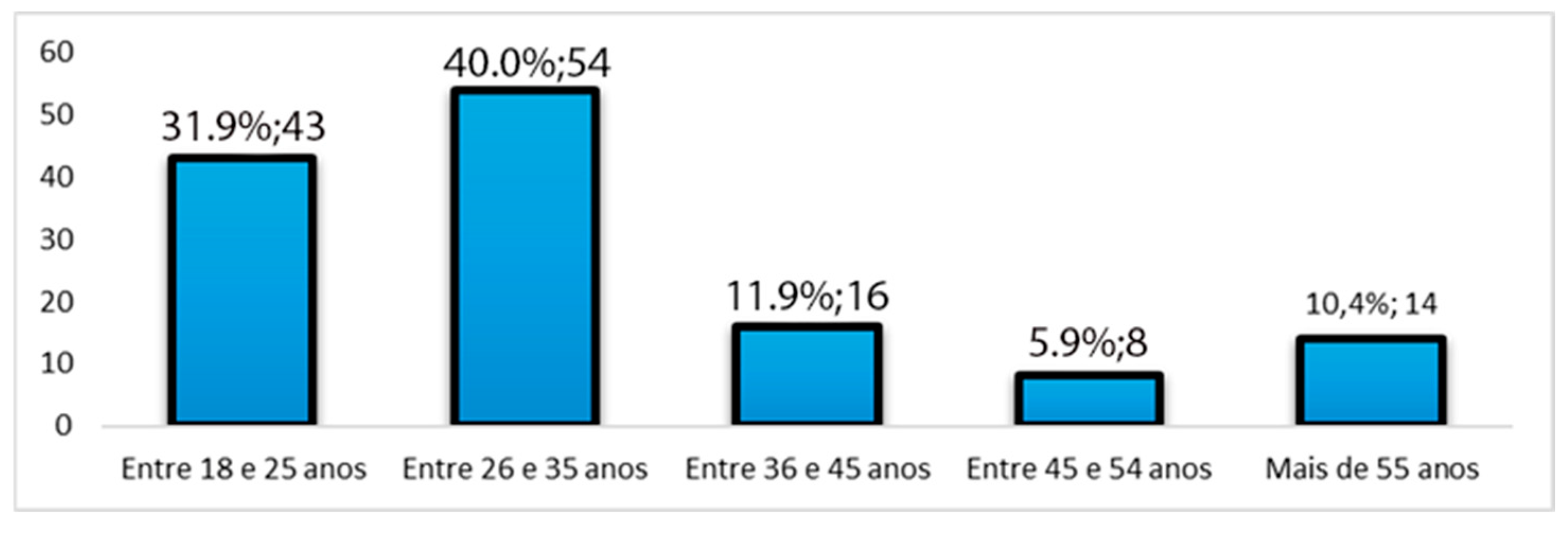

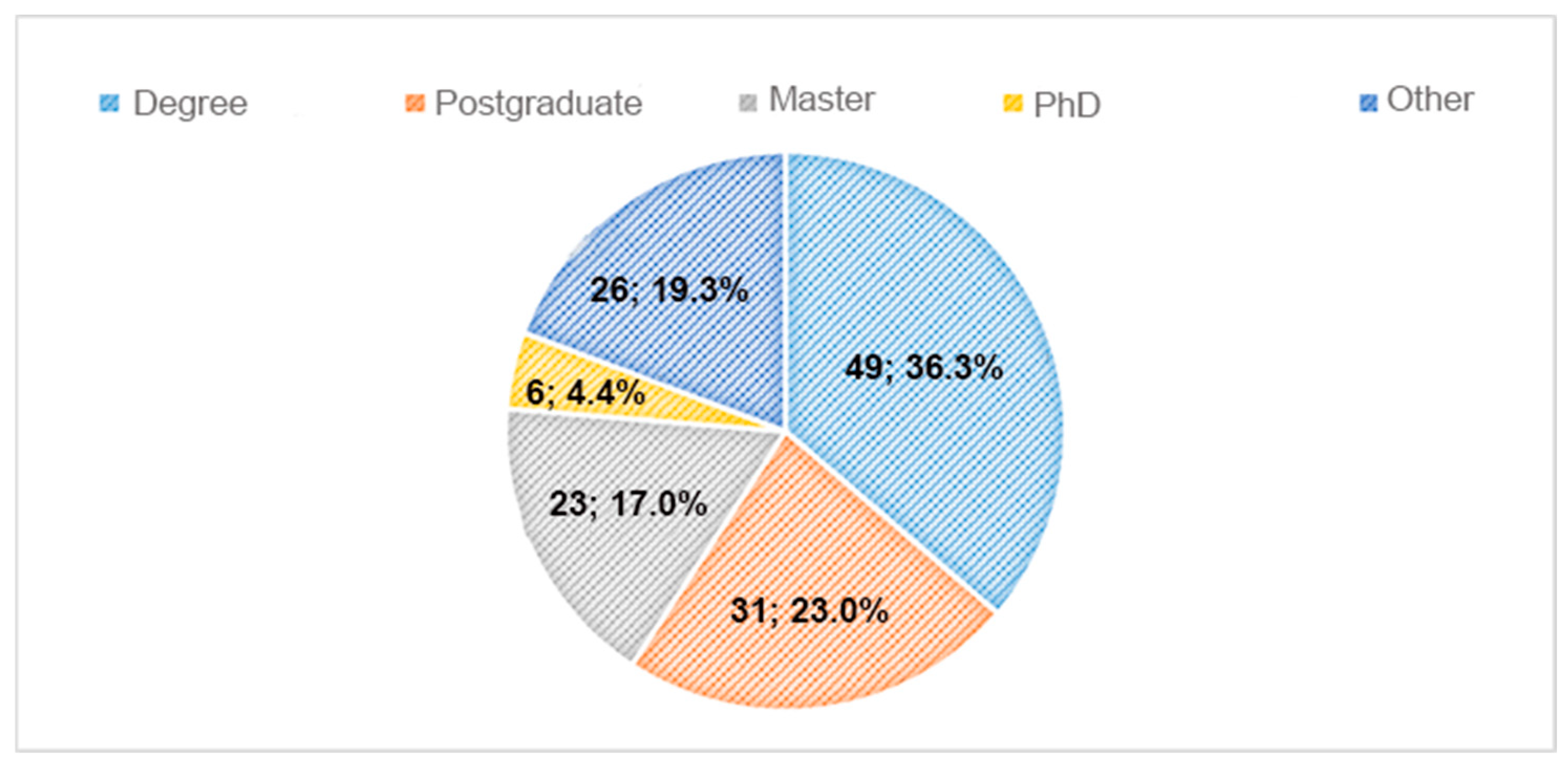

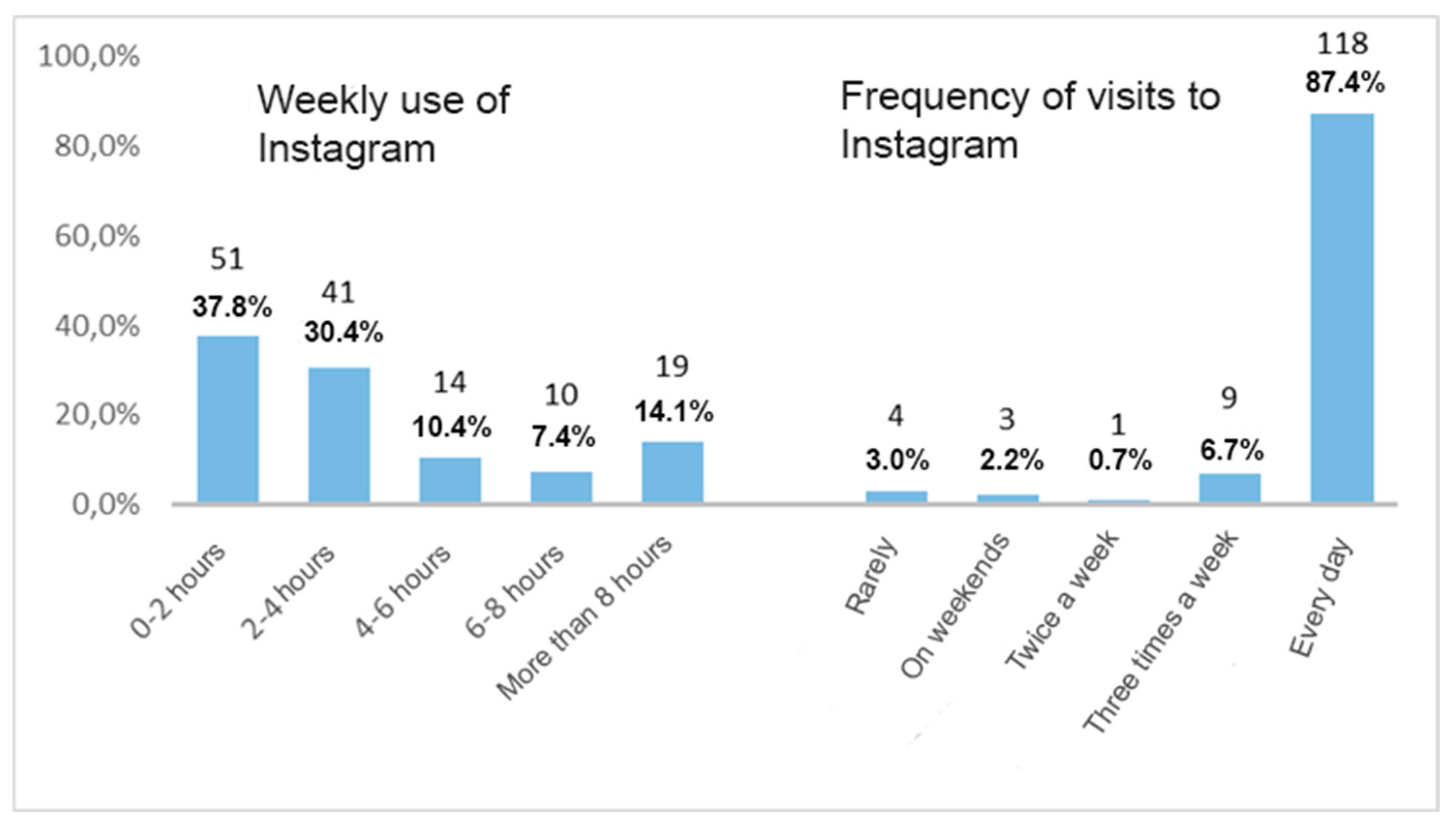

3.4. Study Object and Sample

4. Presentation of Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kemp, S. Digital 2020: 3.8 billion people use social media. We Are Social, 30 January 2020. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2020/01/digital-2020-3-8-billion-people-use-social-media/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Pereira, J.A. Estudo sobre o impacto dos influenciadores digitais na intenção de compra de moda da geração Y e Z. 2022. Available online: https://comum.rcaap.pt/bitstream/10400.26/42555/1/juelma_pereira.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lampeitl, A.; Åberg, P. The Role of Influencers in Generating Customer-Based Brand Equity & Brand-Promoting User-Generated Content. 2017. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8921874&fileOId=8921875 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Pop, R.-A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Dabija, D.-C.; Alt, M.-A. The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.C. The role of social media influencers on the consumer decision-making process. In Research Anthology on Social Media Advertising and Building Consumer Relationships; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1420–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, J.; Fedorko, R. The Impact of Influencers on Consumers’ Purchasing Decisions When Shopping Online. In Proceedings of the Digital Marketing & eCommerce Conference; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Santos-Roldán, L.M.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk in influencers’ product recommendations on their followers’ purchase attitudes and intention. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 184, 121997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.I.S.d.; Coelho, R.L.F.; Camilo-Junior, C.G.; Godoy, R.M.F.d. Quem lidera sua opinião? Influência dos formadores de opinião digitais no engajamento. Rev. De Adm. Contemp. 2018, 22, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Kumar, N.; Gupta, R.; Baber, H.; Venkatesh, A. How social media influencers impact consumer behaviour? Systematic literature review. Vision 2024, 09722629241237394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Behaviour. Int. Sci. J. Eng. Manag. 2024, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, B.; Wen, X.; Nazir, A.; Junaid, D.; Silva, L.J.O. Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lieva, G.; Yankova, T.; Ruseva, M.; Dzhabarova, Y.; Klisarova-Belcheva, S.; Bratkov, M. Social Media Influencers: Customer Attitudes and Impact on Purchase Behaviour. Information 2024, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B.; Henderson, K. Opinion leadership in a computer-mediated environment. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Lin, C.-P. Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: The mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, G.; Reisdorf, B.C. The Participatory Web. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundecha, P.; Liu, H. Mining social media: A brief introduction. New Dir. Inform. Optim. Logist. Prod. 2012, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-S.; Sin, S.-C.J.; Yoo-Lee, E.Y. Undergraduates’ use of social media as information sources. Coll. Res. Libr. 2014, 75, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoğlu, E.; Kip, S.M. Brand communication through digital influencers: Leveraging blogger engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskorski, M.; Brooks, G. Online broadcasters: How do they maintain influence, when audiences know they are paid to influence. Proc. 2017 Winter AMA 2017, 28, D70–D80. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, A.; Dekhil, F.; Djemel, T. Endorsement by celebrities: The role of congruence. Her. J. Mark. Bus. Manag. 2012, 1, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- KS, H.; Kurup, M.S.K. Effectiveness of television advertisement on purchase intention. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2014, 3, 9416–9422. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Bhakar, S. Does celebrity image congruence influences brand attitude and purchase intention? J. Promot. Manag. 2018, 24, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, P. Consumer-Generated Media (CGM) 101: Word-of-Mouth in the Age of the Web-Fortified Consumer. 2004. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Consumer-Generated-Media-(CGM)-101-%3A-Word-of-mouth-Blackshaw/596da0237a279f1ec6c65ab06ba351767699a194 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-branding,’micro-celebrity’and the rise of social media influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2017, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aced, C.; Lalueza, F. How (Spanish) companies are using social media: A proposal for a qualitative assessment tool. Intl. Conf. Soc. e-Xperience 2012, 6, 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, W.; Ye, Z.; Wan, S.; Yu, P.S. Web 3.0: The Future of Internet. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.06032. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, P.; Sutherland, K.E. Public relations practitioners and social media: Themes in a global context. In Proceedings of the World Public Relations Forum, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 18 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, D.K.; Hinson, M.D. An analysis of the increasing impact of social and other new media on public relations practice. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Public Relations Research Conference, Miami, FL, USA, 14 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, M. Impact of promotional marketing using Web 2.0 tools on purchase decision of Gen Z. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lies, J. Marketing Intelligence and Big Data: Digital Marketing Techniques on Their Way to Becoming Social Engineering Techniques in Marketing. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha, A.P.; Abreu, A.J.; Angélico, M.J.; da Silva, A.F.; Teixeira, S. A content analysis of social media in tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. In International Conference on Tourism, Technology and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualman, E. Socialnomics: How Social Media Transforms the Way We Live and Do Business; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aced, C. Relaciones Públicas 2.0: Cómo Gestionar la Comunicación Corporativa en el Entorno Digital; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; pp. 1–226. [Google Scholar]

- Grunig, J.E. Paradigms of global public relations in an age of digitalisation. PRism 2009, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Macnamara, J. Public relations and the social: How practitioners are using, or abusing, social media. Asia Pac. Public Relat. J. 2010, 11, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Casaló, L.V.; Cisneros, J.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Determinants of success in open source software networks. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Angriawan, A.; Summey, J.H. Technological opinion leadership: The role of personal innovativeness, gadget love, and technological innovativeness. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2764–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothi, P.S.; Neelamalar, M.; Prasad, R.S. Analysis of social networking sites: A study on effective communication strategy in developing brand communication. J. Media Commun. Stud. 2011, 3, 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.L. Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, F.; Bródka, P.; Borg, A.; Johnson, H. Finding influential users in social media using association rule learning. Entropy 2016, 18, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, B.K. Using social media to our advantage: Alleviating anxiety during a pandemic. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Online consumer review: Word-of-mouth as a new element of marketing communication mix. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facebook. Bringing You Closer to the People and Things You Love. Instagram. 2023. Available online: https://about.instagram.com (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Jin, S.V.; Muqaddam, A.; Ryu, E. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Instagram: Distribution of Global Audiences 2021, by Age Group. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/325587/instagram-global-age-group/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Han, I. What drives the adoption of mobile data services? An approach from a value perspective. J. Inf. Technol. 2009, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.D.; Parboteeah, V.; Valacich, J.S. Online impulse buying: Understanding the interplay between consumer impulsiveness and website quality. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütter, M. The impact of social media on consumer buying intention. Marketing 2017, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcharat, T.; Leelasantitham, A. A retentive consumer behavior assessment model of the online purchase decision-making process. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratchatanon, O.; Sanlekanan, K.; Klinsukon, C.; Phu-ngam, J. The impact of e-commerce business on local entrepreneurs. Res. Rep. Bank Thailand. Bangk. Bank Thail. 2016, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stankevich, A. Explaining the consumer decision-making process: Critical literature review. J. Int. Bus. Res. Mark. 2017, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M.R.; Dahl, D.W.; White, K.; Zaichkowsky, J.L.; Polegato, R. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamis, A.; Koufaris, M.; Stern, T. Using an attribute-based decision support system for user-customized products online: An experimental investigation. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Botti, S.; Faro, D. Turning the page: The impact of choice closure on satisfaction. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, V.; Yoon, K.; Zahedi, F.M. The measurement of web-customer satisfaction: An expectation and disconfirmation approach. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBarbera, P.A.; Mazursky, D. A longitudinal assessment of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction: The dynamic aspect of the cognitive process. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Princípios de Marketing; Pearson Prentice Hall: Bridge, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, H. Effects of various characteristics of social commerce (s-commerce) on consumers’ trust and trust performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P.; Turban, E. Introduction to the special issue social commerce: A research framework for social commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Papamichail, K.N.; Holland, C.P. The effect of prior knowledge and decision-making style on the online purchase decision-making process: A typology of consumer shopping behaviour. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 77, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.G.; Ratneshwar, S.; Mohanty, P. The time-harried shopper: Exploring the differences between maximizers and satisficers. Mark. Lett. 2009, 20, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.M.A.G.; Gonçalves, M.J.A. Aplicações Móveis na Sala de Aula de Línguas no 2º e 3º Ciclo. RTIC-Rev. De Tecnol. Informação Comun. 2021, 2, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, M.; Lehmann, D.R.; Herrmann, A. Choice goal attainment and decision and consumption satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akand, F. Impact of social media influencers on purchase intentions: A comprehensive study across industries. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Updat. 2024, 7, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanief, F.A.; Oktini, D.R. Pengaruh Influencer Marketing dan Social Media Marketing terhadap Keputusan Pembelian. Bdg. Conf. Ser. Bus. Manag. 2024, 4, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, M.; Cao, T.; Wang, S.; Qiao, C. Marketing Strategy in the Digital Age: Applying Kotler’s Strategies to Digital Marketing; World Scientific: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.; Hayes, N. Influencer Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, J.; Bhattacharya, M. Impact of social media influencers on brand awareness: A study on college students of Kolkata. Commun. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Cartano, D.G. Methods of measuring opinion leadership. Public Opin. Q. 1962, 62, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Bernardes, Ó.; Gonçalves, M.J.A.; Terra, A.L.; da Silva, M.M.; Tavares, C.; Valente, I. E-Learning Enhancement through Multidisciplinary Teams in Higher Education: Students, Teachers, and Librarians. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kfairy, M.; Shuhaiber, A.; Al-Khatib, A.W.; Alrabaee, S. Social Commerce Adoption Model Based on Usability, Perceived Risks, and Institutional Trust. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 3599–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kfairy, M.; Shuhaiber, A.; Al-Khatib, A.W.; Alrabaee, S.; Khaddaj, S. Understanding trust drivers of Scommerce. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.C. O Impacto dos Estímulos do Instagram na Tendência para Comprar por Impulso Online Pela Geração Z: Setor da Moda. Ph.D. Thesis, IPAM, Port, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rauniar, R.; Rawski, G.; Yang, J.; Johnson, B. Technology acceptance model (TAM) and social media usage: An empirical study on Facebook. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.R.D. Os Determinantes da Intenção de Compra dos Consumidores Através do Instagram. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, Escola Superior de Comunicação Social, Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Razac, R. Impacto dos Influenciadores Digitais. 2018. Available online: https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/17496 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Portelada, B. Os Influenciadores Digitais e a Decisão de Compra dos Seguidores da Rede Social Instagram. Master Dissertation, Politécnico do Porto, Instituto Superior de Contabilidade e Administração do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Villinger, A. O Impacto do Word-of-Mouth Eletrónico na Atitude Relativamente à Marca e na Intenção de Compra. Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, Escola Superior de Comunicação Social: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gondaski, A.S.M.R. O Impacto das Atividades de Marketing no Instagram no Comportamento do Consumidor e na Lealdade à Marca. Master Thesis, Instituto Politecnico de Leiria, Leiria, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, M.J.; Baptista, C.S. Como Fazer Investigação, Dissertações, Tese e Relatórios-Segundo Bolonha (5a Edição). 2014. Available online: https://www.wook.pt/livro/como-fazer-investigacao-dissertacoes-tese-e-relatorios-cristina-sales-baptista/11006357 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.N.; Fischer, E.; Yongjian, C. How does brand-related user-generated content differ across YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter? J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Constructs | Sources | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of use | 1: [89] | 1. Do you have an active Instagram account? |

| 1 and 2: [90] | 1. How often do you visit Instagram? | |

| 2. On average, how many hours a week do you use Instagram? | ||

| 1 and 2: [91] | 1. Instagram is part of my daily activities | |

| 2. Instagram has become part of my routine | ||

| 1 [73] | 1. I use Instagram frequently during my week | |

| Perceived usefulness | 1, 2, and 3: [73] | 1. Using Instagram improves my performance as a consumer |

| 2. Using social media and Instagram is useful to me | ||

| 3. Using Instagram is useful for my consumer activities | ||

| Ease of use | 1, 2, and 3: [73] | 1. Using Instagram is easy for me |

| 2. I find it easy to interact with Instagram | ||

| 3. I feel comfortable and confident using Instagram | ||

| 1: [92] | 1. Using Instagram requires no mental effort on my part | |

| Attitudes | 1, 2, and 3: [92] | 1. I find Instagram an interesting way to get in touch with brands |

| 2. I find Instagram an interesting way to search for information about brands/products/services | ||

| 3. I see Instagram as a means of sharing knowledge | ||

| 1 and 2: [93] | 1. I like to buy products/services that have been recommended on Instagram. | |

| 2. I’m interested in buying products/services that have been recommended on Instagram. | ||

| Reasons | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6: [92] | 1. I follow brands on Instagram that I consume or buy |

| 2. I think that my interest in following a brand on Instagram is related to my satisfaction with the brand | ||

| 3. Following brands on Instagram helps me acquire information about new offers | ||

| 4. I like the influence and creative content on Instagram that is created by brands | ||

| 5. I think that product-related information obtained through Instagram is relatively reliable | ||

| 6. Instagram is a reliable source of information because it enables transparent communication between the brand and the consumer | ||

| Digital influencers | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6: [94] | 1. On Instagram, when an influencer demonstrates a product, I feel the need to look for more information about the product |

| 2. I feel that an influencer who interacts with their Instagram followers on a daily basis has a greater influence on purchasing decisions. | ||

| 3. I believe that the more followers on social media, particularly Instagram, the more credible the influencer is | ||

| 4. The greater the number of social media partnerships an influencer has, the more impact their communication has on products | ||

| 5. I tend to follow digital influencers with more followers on Instagram | ||

| 6. I have already become a customer of a brand or product through a digital influencer on Instagram | ||

| 1, 2, and 3: [93] | 1. I’m inclined to accept the opinions of digital influencers’ opinions on products/services on social media | |

| 1: [83] | 1. I am influenced by recommendations of | |

| Word of mouth | 1, 2, 3, and 4: [95] | 1. I use social networks to write (posts, comments) about the prices charged by a brand |

| 2. I use social media, particularly Instagram, to write (posts, comments) about my negative personal experience with a brand | ||

| 3. I use social media, particularly Instagram, to express (with posts, comments) any doubts I have about a brand. | ||

| 4. I write comments, opinions and/or information on Instagram because I want to help other users with my own experiences | ||

| 1, 2, 3, and 4: [92] | 1. I suggest products I like to my friends on Instagram | |

| 2. I comment on products and profiles of brands I like on Instagram | ||

| 3. I recommend other users to buy products online via Instagram | ||

| 4. Instagram allows me to get advice from other users before deciding on my purchase | ||

| Trust in the brand | 1, 2, 3, and 4: [96] | 1. I’d rather buy from my favourite brand than try one I don’t know |

| 2. I always buy from the brands I follow on Instagram | ||

| 3. I consider myself loyal to the product/service brands I follow on Instagram | ||

| 4. I follow/follow the brand of the products/services I buy on Instagram | ||

| Purchase intention | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7: [93] | 1. Communication on Instagram influences my opinions and feelings about products/services |

| 2. Communication on Instagram helps me remember products/services | ||

| 3. Communication on Instagram is useful when I’m deciding which brand or product to buy | ||

| 4. When deciding to buy a product/service, I’ll consider buying the one recommended by a digital influencer | ||

| 5. The likelihood of buying products/services recommended by digital influencers is high | ||

| 6. The communication made by digital influencers on Instagram influences the consumer’s intention to buy | ||

| 7. The communication of products/services on Instagram helps me make purchasing decisions |

| Construct | Indicator | Indicator Description | Outer Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of use | FreqU3 | Instagram is part of my daily activities | 0.946 |

| CR = 0.946 | FreqU4 | Instagram has become part of my routine | 0.950 |

| AVE = 898 | |||

| Trust in the brand | ConfM3 | I follow/follow the brand of the products/services I buy on Instagram | 0.863 |

| CR = 0.872 | ConfM4 | Communication on Instagram influences my opinions and feelings about products/services | 0.894 |

| AVE = 773 | |||

| Word of Mouth | WoM4 | I suggest products I like to my friends on Instagram | 0.827 |

| CR = 0.876 | WoM6 | I comment on products and profiles of brands I like on Instagram | 0.843 |

| AVE = 0.703 | WoM7 | I recommend other users to buy products online via Instagram | 0.844 |

| Attitudes | Att2 | I find Instagram an interesting way to search for information about brands/products/services | 0.691 * |

| CR = 0.892 | Att4 | I see Instagram as a means of sharing knowledge | 0.932 |

| AVE = 737 | Att5 | I like to buy products/services that have been recommended on Instagram. | 0.929 |

| Reasons | Mot1 | I follow brands on Instagram that I consume or buy | 0.841 |

| CR = 0.895 | Mot2 | I think that my interest in following a brand on Instagram is related to my satisfaction with the brand | 0.813 |

| AVE = 0.681 | Mot3 | Following brands on Instagram helps me acquire information about new offers | 0.827 |

| Mot4 | I like the influence and creative content on Instagram that is created by brands | 0.818 | |

| Digital Influencers | InfDig1 | On Instagram. when an influencer demonstrates a product, I feel the need to look for more information about the product | 0.720 |

| CR = 0.915 | InfDig6 | I feel that an influencer who interacts with their Instagram followers on a daily basis has a greater influence on purchasing decisions. | 0.833 |

| AVE = 0.684 | InfDig7 | I believe that the more followers on social media, particularly Instagram, the more credible the influencer is | 0.874 |

| InfDig8 | The greater the number of social media partnerships an influencer has, the more impact their communication has on products | 0.913 | |

| InfDig9 | I tend to follow digital influencers with more followers on Instagram | 0.781 | |

| Perceived Usefulness | UtP1 | Using Instagram improves my performance as a consumer | 0.899 |

| CR = 0.881 | UtP2 | Using social media and Instagram is useful to me | 0.723 |

| AVE = 0.713 | UtP3 | Using Instagram is useful for my consumer activities | 0.899 |

| Ease of use | FacU1 | Using Instagram is easy for me | 0.914 |

| CR = 0.914 | FacU2 | I find it easy to interact with Instagram | 0.929 |

| AVE = 0.781 | FacU3 | I feel comfortable and confident using Instagram | 0.803 |

| Purchase Intention | IC1 | Communication on Instagram helps me remember products/services | 0.726 |

| CR = 0.894 | IC2 | Communication on Instagram is useful when I’m deciding which brand or product to buy | 0.855 |

| AVE = 0.680 | IC3 | When deciding to buy a product/service, I’ll consider buying the one recommended by a digital influencer | 0.848 |

| IC4 | The likelihood of buying products/services recommended by digital influencers is high | 0.861 |

| Attitudes | Trust in the Brand | Ease of Use | Frequency of Use | Digital Influencers | Purchase Intention | Reasons | Perceived Usefulness | Word of Mouth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | 0.858 | ||||||||

| Trust in the brand | 0.531 | 0.879 | |||||||

| Ease of use | 0.373 | 0.244 | 0.884 | ||||||

| Frequency of use | 0.359 | 0.196 | 0.492 | 0.948 | |||||

| Digital Influencers | 0.635 | 0.702 | 0.230 | 0.318 | 0.83 | ||||

| Purchase Intention | 0.505 | 0.777 | 0.135 | 0.100 | 0.776 | 0.83 | |||

| Reasons | 0.507 | 0.585 | 0.452 | 0.397 | 0.502 | 0.376 | 0.83 | ||

| Perceived Usefulness | 0.562 | 0.328 | 0.260 | 0.518 | 0.504 | 0.360 | 0.394 | 0.844 | |

| Word of Mouth | 0.447 | 0.612 | 0.196 | 0.207 | 0.544 | 0.55 | 0.338 | 0.323 | 0.838 |

| Q2 | |

|---|---|

| Ease of use | 0.216 |

| Purchase Intention | 0.613 |

| Perceived Usefulness | 0.401 |

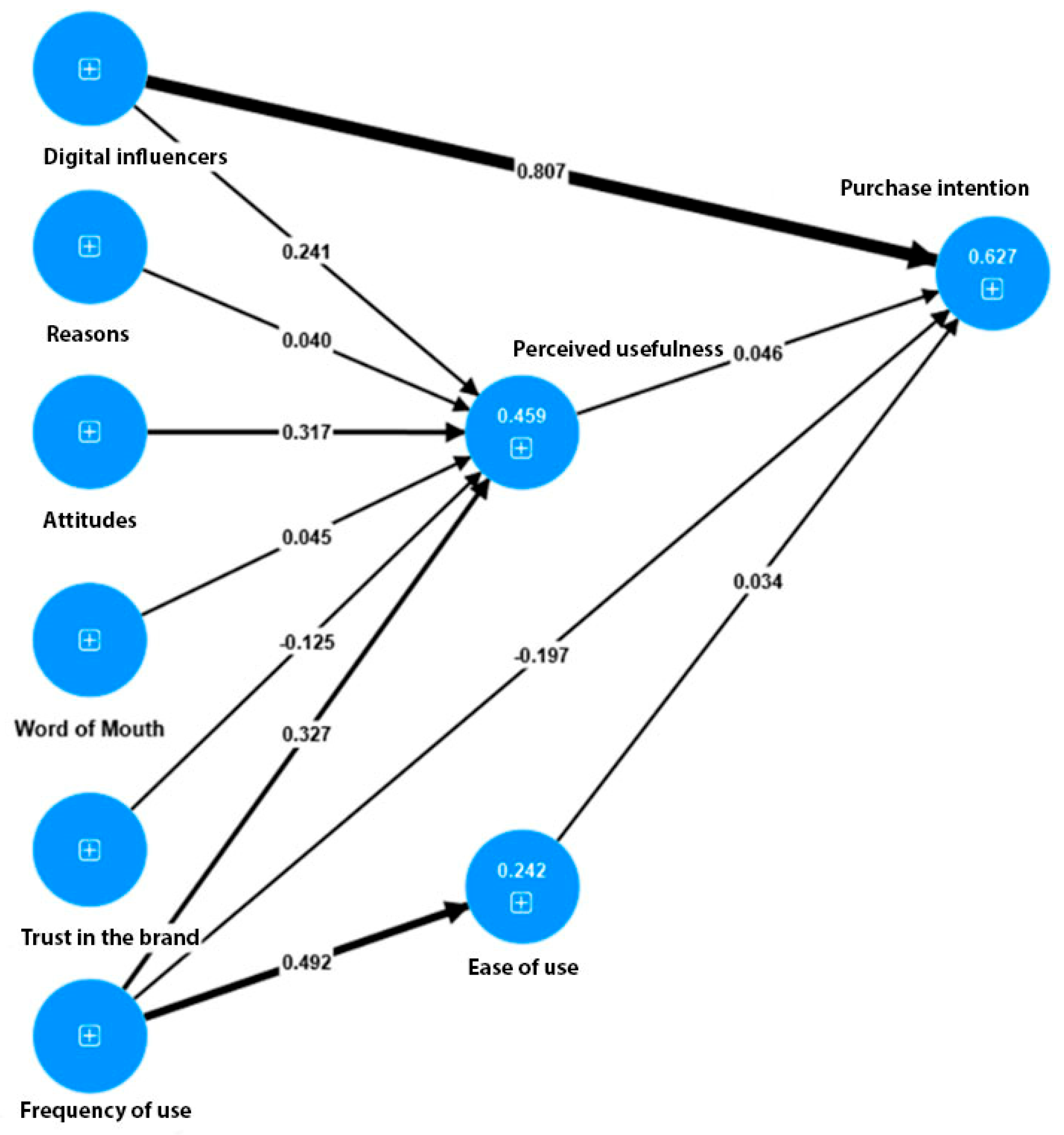

| b | DP | T Student (b/DP) | p-Value | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 Attitudes ⇨ Perceived usefulness | 0.317 | 0.097 | 3.280 | 0.001 | ✔ |

| H2 Trust in the brand ⇨ Perceived usefulness | −0.125 | 0.105 | 1.191 | 0.234 | X |

| H3 Frequency of use ⇨ Purchase intention | 0.034 | 0.049 | 0.679 | 0.497 | X |

| H4 Frequency of use ⇨ Ease of use | 0.492 | 0.082 | 6.017 | <0.001 | ✔ |

| H5 Frequency of use ⇨ Purchase intention | −0.197 | 0.071 | 2.770 | 0.006 | ✔ |

| H6 Frequency of use ⇨ Perceived usefulness | 0.327 | 0.072 | 4.566 | <0.001 | ✔ |

| H7 Digital influencers ⇨ Purchase intention | 0.807 | 0.053 | 15.345 | <0.001 | ✔ |

| H8 Digital influencers ⇨ Perceived usefulness | 0.241 | 0.098 | 2.455 | 0.014 | ✔ |

| H9 Reasons ⇨ Perceived usefulness | 0.040 | 0.079 | 0.507 | 0.612 | X |

| H10 Perceived usefulness ⇨ Purchase intention | 0.046 | 0.064 | 0.720 | 0.471 | X |

| H11 Word-of-mouth ⇨ Perceived usefulness | 0.045 | 0.081 | 0.560 | 0.575 | X |

| R2 | Model Adjustment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of use | 0.242 | SRMR = 0.089 NFI = 0.663 | ||

| Purchase Intention | 0.627 | |||

| Perceived Usefulness | 0.459 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, M.J.A.; Oliveira, A.; Abreu, A.; Mesquita, A. Social Networks and Digital Influencers in the Online Purchasing Decision Process. Information 2024, 15, 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100601

Gonçalves MJA, Oliveira A, Abreu A, Mesquita A. Social Networks and Digital Influencers in the Online Purchasing Decision Process. Information. 2024; 15(10):601. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100601

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Maria José Angélico, Adriana Oliveira, António Abreu, and Anabela Mesquita. 2024. "Social Networks and Digital Influencers in the Online Purchasing Decision Process" Information 15, no. 10: 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100601

APA StyleGonçalves, M. J. A., Oliveira, A., Abreu, A., & Mesquita, A. (2024). Social Networks and Digital Influencers in the Online Purchasing Decision Process. Information, 15(10), 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100601