The Future of Higher Education: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in AI-Driven Lifelong Learning in Peru

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To identify the key challenges that Peruvian universities must address in the coming years concerning the future of education.

- This analysis aligns with global educational trends while considering specific factors that could influence the strategic goals of universities in Peru.

- To present an analytical methodology that integrates conceptual analysis, natural language processing and quantitative techniques based on semantic projections, enabling a more in-depth approach to foresight for strategic planning.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

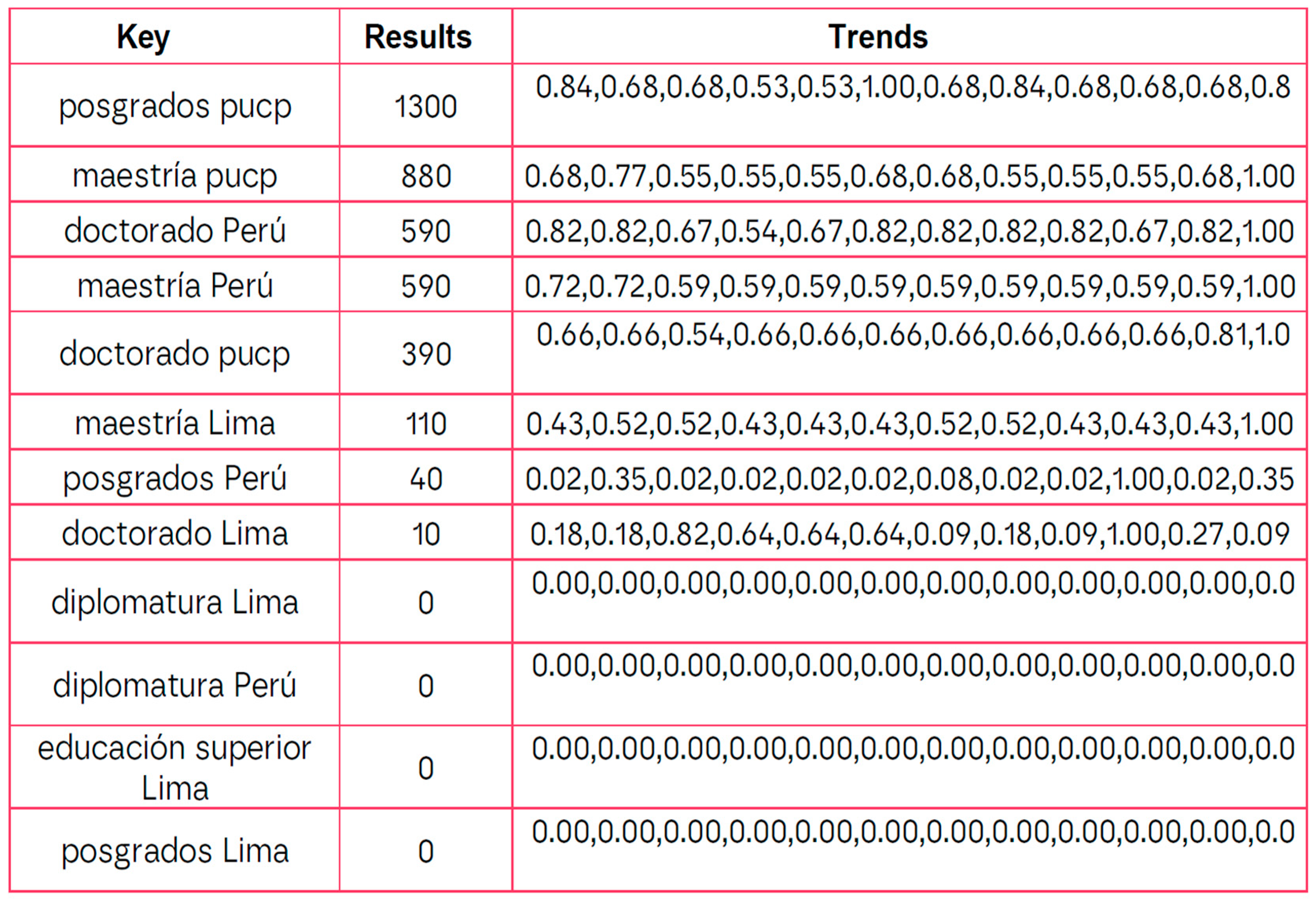

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Validation of Results

3. Results

- Education as a search for and development of talent: talent-availability; talent-development; talent-detection.

- Education based on the development of skills and abilities, which implies a paradigm shift towards practical approaches in teaching: skills-knowledge; skills-share; training-comprehensive; skills-engagement; share-reskilling; skills-training; skills-cognitive; skills-self

- Turn towards the knowledge-based economy and promoted through economic and social achievements: education-attainment; organizations-knowledge.

- Education and new technologies: Education-technologies; education-workforce; education-4.0.

- Adaptability and flexibility scenario: it is projected that, by 2030, 40% of programmes will use hybrid and flexible formats, allowing students to better manage their work and educational commitments.

- Integration of digital services scenario: by 2030, it is expected that the use of digital services and AI-based tools will increase by 50%, optimising the educational experience and improving administrative management.

- Ecosystem collaboration and networking scenario: a 30% increase in collaboration between educational institutions and actors in the productive sector is expected by 2030, promoting joint projects that enrich graduate education programmes.

- -

- Adaptability: Adaptability is essential for educational institutions wishing to adapt to new student demands. By 2030, 40% of programmes are expected to adopt a hybrid format, demonstrating the growing need for personalisation and flexibility in educational approaches.

- -

- Digital services: The adoption of digital services, including AI-based tools, is expected to grow by 50%, improving the efficiency and accessibility of educational programmes.

- -

- People and Culture: This group focuses on student empowerment and active participation. Gen Z, a demographic seeking more dynamic and personalised learning experiences, showed a preference for digital content in 65% of cases.

- -

- Ecosystems: Collaborative networks between educational institutions and the productive sector are essential for innovation. A 30% increase in inter-institutional agreements and joint projects is expected, which will enrich the PUCP’s educational offer.

- -

- Collaboration: Cooperation between the different actors in the education ecosystem will be key to innovation. This collaboration includes not only academic institutions, but also companies in the productive sector that can support the development of skills relevant to the labour market.

- -

- Work transformation: The work environment is being transformed by digitalisation and automation, which requires graduate education to provide advanced competencies in these areas. Students need to develop specific skills to navigate an increasingly automated labour market

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Trend | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | E11 | E12 | E13 | E14 | E15… |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 10 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 11 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 12 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 13 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 14 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 15 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 16 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 17 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 18 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 19 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 20 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 21 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 22 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 23 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 24 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 25 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 26 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 27 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 28 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 29 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 30 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

References

- Abulibdeh, A.; Zaidan, E.; Abulibdeh, R. Navigating the confluence of artificial intelligence and education for sustainable development in the era of industry 4.0: Challenges, opportunities, and ethical dimensions. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 437, 140527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG International. The Future of Higher Education in a Disruptive World. 2020. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/what-we-do/industries/government/education/the-future-of-higher-education-in-a-disruptive-world.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Lara-Navarra, P.; Sánchez-Pérez, E.A.; Ferrer-Sapena, A.; Fitó-Bertran, À. Singularity in higher education: Methods for detection and classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 239, 122306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Kanuka, H. Blended Learning: Uncovering its Transformative Potential in Higher Education. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasa, T. Education and the Future: Four Orientations. Eur. J. Educ. 2024, 60, e12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukan, E.; Tawil, S. A new social contract for education: Rebuilding trust in education as a common good. Prospects 2024, 54, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A. The Future of Higher Education. 2024. Available online: https://www.adlittle.com/sites/default/files/reports/ADL_Future_of_higher_education_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Manetti, A.; Lara-Navarra, P.; Sánchez-Navarro, J. El proceso de diseño para la generación de escenarios futuros educativos. Comun. Rev. Científica Iberoam. Comun. Educ. 2022, 30, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojan, M.P.; Lara-Navarra, P.; Sánchez-Navarro, J. Profiling soft skills in the labour market: The case of communication. In Research and Innovation Forum 2023; Visvizi, A., Troisi, O., Corvello, V., Eds.; RIIFORUM 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Belchior-Rocha, H.; Casquilho-Martins, I.; Simões, E. Transversal competencies for employability: From higher education to the labour market. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Lauder, H.; Ashton, D. The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs, and Incomes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Catalysing Education 4.0: Investing in the Future of Learning for a Human-Centric Recovery. 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/catalysing-education-4-0-investing-in-the-future-of-learning-for-a-human-centric-recovery/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Lavado, P.; Martínez, J.; Yamada, G. ¿Una Promesa Incumplida? La Calidad de la Educación Superior Universitaria y el Subempleo Profesional en el Perú; Working Paper Series, DT 2014 021; Banco Central del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Center on Education Policy. For the Common Good: Recommitting to Public Education in a Time of Crisis. Center on Education Policy. 2020. Available online: https://www.cep-dc.org/displayDocument.cfm?DocumentID=147 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- United Nations. Global Citizenship Education for a More Just and Equitable World. United Nations. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/global-citizenship-education-more-just-and-equitable-world (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M.; Mulà, I. Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development: Emerging Teaching and Research Developments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, R. Education as a Public and Common Good: Reframing the Governance of Education in a Changing Context. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2018. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261614 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Tikly, L. The future of Education for All as a global regime of educational governance. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2017, 61, 22–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branica, V.; Opačić, A. Lifelong learning between professional identity, structural changes, and professional regulation in social work. In The Routledge International Handbook of Social Work Teaching, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; p. 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson Lindqvist, M.; Mozelius, P.; Jaldemark, J.; Cleveland Innes, M. Higher education transformation towards lifelong learning in a digital era—A scoping literature review. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2023, 43, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimes Campos, M.A.; Campos Cornejo, L.L. Labor expectations from students of private and public universities in Peru. Int. J. Educ. Policy Res. Rev. 2019, 6, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz Rivera, P.Y.; Yangali Vicente, J.S. Factors influencing the labour market insertion of undergraduate graduates from Peruvian universities. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 4740–4749. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, P.; Sivesind, K.; Thostrup, R. Managing expectations by projecting the future school: Observing the Nordic future school reports via temporal topologie. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 20, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S. Generations X, Y, Z: The effects of personal and positional inequalities on critical thinking digital skills. Online Inf. Rev. 2025, 49, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Manetti, A.; Ferrer-Sapena, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, E.A.; Lara-Navarra, P. Design trend forecasting by combining conceptual analysis and semantic projections: New tools for open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-Cot, F.; Lara-Navarra, P.; Serradell-López, E.; Manetti, A. Design-driven external analysis: A framework for adaptation and innovation in digitally native enterprises. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantú-Ortiz, F.J.; Galeano Sánchez, N.; Garrido, L.; Terashima-Marin, H.; Brena, R.F. An artificial intelligence educational strategy for the digital transformation. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2020, 14, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Chiriatti, M. GPT-3: Its Nature, Scope, Limits, and Consequences. Minds Mach. 2020, 30, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghnemat, R.; Shaout, A.; Al-Sowi, A.M. Higher education transformation for artificial intelligence revolution: Transformation framework. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, M.; Katebzadah, S.; Fazil, A.W. Comprehensive Insights Into E-Learning in Contemporary Education: Analyzing Trends, Challenges, and Best Practices. J. Educ. Teach. Learn. 2024, 6, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Infante Moro, A. Empleo del método Delphi y su empleo en la investigación en comunicación y educación. Edutec Rev. Electrón. Tecnol. Educ. 2014, 48, a272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, B.; Pascual-Ezama, D. La metodología Delphi como técnica de estudio de la validez de contenido. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2012, 28, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDUCAUSE. EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and Learning Edition. 2023. Available online: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2023/5/2023-educause-horizon-report-teaching-and-learning-edition (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Alexander, A.; Manolchev, C. The future of university or universities of the future: A paradox for uncertain times. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 34, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K.; Tlili, A.; Schunka, L.; Salha, S.; Saiti, A. Reimagining Educational Leadership and Management Through Artificial Intelligence: An Integrative Systematic Review. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2025, 24, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, N.J.; Jones, S.; Smith, D.P. Generative AI in higher education: Balancing innovation and integrity. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 81, 14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafezi, R.; Ghaboulian Zare, S.; Taghikhah, F.R.; Roshani, S. How universities study the future: A critical view. Futures 2024, 163, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, M.; Karataş, İ.H.; Varol, N. Ethical Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Educational Leadership: Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2025, 24, 46–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, S.; Koh, J.H.L.; Daniel, B.K. Correction: A systematic review of the opportunities and challenges of micro-credentials for multiple stakeholders: Learners, employers, higher education institutions and government. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihendro, H.L.; Warnars, H.S.; Prabowo, H.; Sfenrianto. Understanding the definitions of microcredentials in higher education: Systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on TVET Excellence & Development (ICTeD), Melaka, Malaysia, 16–17 December 2024; pp. 188–194. [CrossRef]

- Grybauskas, A.; Pilinkienė, V.; Lukauskas, M.; Stundžienė, A.; Bruneckienė, J. Nowcasting Unemployment Using Neural Networks and Multi-Dimensional Google Trends Data. Economies 2023, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Kim, Y.; Cho, Y.-N. Digital Marketing and Analytics Education: A Systematic Review. J. Mark. Educ. 2024, 46, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Kirby, J. Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.; Smith, L. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Samala, A.D.; Rawas, S.; Criollo, C.S.; Bojic, L.; Prasetya, F.; Ranuharja, F.; Marta, R. Emerging technologies for global education: A comprehensive exploration of trends, innovations, challenges, and future horizons. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-de-Menendez, M.; Escobar Díaz, C.A.; Morales-Menendez, R. Educational experiences with Generation Z. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2020, 14, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemiller, C.; Grace, M. Generation Z: Educating and engaging the next generation of students. J. Educ. Pract. 2023, 22, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy–and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood; Atria Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies; W.W. Norton & Company: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H.; Prusak, L. Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know; Harvard Business Review Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Customisation | 11. Staying in education longer | 21. Business mash-ups |

| 2. Personalisation | 12. Direct democracy | 22. Labor shortages |

| 3. Individualisation | 13. Population Aging | 23. Hyperconnectivity |

| 4. Empowerment | 14. Gen Z Rising | 24. Greater Interconnectedness |

| 5. Multiculturalism | 15. Customised learning | 25. Applied Adaptive AI |

| 6. Beyond Globalisation | 16. Rising levels of education | 26. Synthetic media |

| 7. Digital Culture | 17. Changing Business Volatility | 27. AI risks for business |

| 8. Digital Natives | 18. Service Economy | 28. Intelligent environments |

| 9. New ways of Working | 19. Knowledge-based economy | 29. Technology Convergence |

| 10. Reimagine work | 20. Innovation as a key driver | 30. Digital Self-actualisation |

| Continuing Education | 0.6 | Labour innovation | 0.45 | Personalisation | 0.35 | Global education | 0.2 |

| Personal growth | 0.55 | Digital services | 0.42 | Digital culture | 0.35 | Citizen participation | 0.18 |

| Service Economy | 0.55 | Artificial Intelligent | 0.4 | Virtual Media | 0.35 | Artificial Intelligence | 0.15 |

| Knowledge Economy | 0.5 | Education Industry | 0.35 | Personalised Services | 0.2 | AI-Generated Content | 0.15 |

| Transformation | 0.5 | AI Risk Management | 0.35 | Online Self-Realisation | 0.2 | Gen Z | 0.12 |

| Terms | Count | Terms | Count | Terms | Count | Terms | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| global | 1276 | jobs | 485 | abilities | 362 | transformation | 258 |

| skills | 1193 | higher | 482 | years | 351 | retention | 257 |

| share | 1155 | skill | 465 | key | 351 | machine | 255 |

| education | 1136 | outlook | 453 | upskilling | 337 | service | 252 |

| learning | 1063 | reskilling | 448 | economic | 327 | hiring | 246 |

| surveyed | 1009 | growth | 446 | roles | 323 | comprehensive | 239 |

| organizations | 959 | effect | 441 | services | 320 | experience | 229 |

| talent | 912 | workers | 436 | world | 319 | student | 225 |

| job | 903 | digital | 432 | dei | 318 | potential | 220 |

| training | 850 | technology | 430 | teaching | 311 | inclusion | 219 |

| net | 731 | labour | 408 | average | 306 | source | 217 |

| business | 620 | students | 399 | environmental | 302 | ordered | 214 |

| data | 611 | social | 393 | managers | 301 | hours | 213 |

| companies | 584 | workforce | 386 | churn | 299 | consumers | 212 |

| impact | 562 | thinking | 386 | availability | 299 | online | 210 |

| industry | 522 | ai | 376 | new | 291 | displacer | 207 |

| improve | 510 | expected | 374 | economy | 286 | creative | 207 |

| future | 502 | management | 371 | institutions | 281 | components | 206 |

| development | 487 | report | 362 | percent | 275 | analytical | 205 |

| technologies | 485 | abilities | 362 | change | 272 | lifelong | 199 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lara-Navarra, P.; Ferrer-Sapena, A.; Ismodes-Cascón, E.; Fosca-Pastor, C.; Sánchez-Pérez, E.A. The Future of Higher Education: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in AI-Driven Lifelong Learning in Peru. Information 2025, 16, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030224

Lara-Navarra P, Ferrer-Sapena A, Ismodes-Cascón E, Fosca-Pastor C, Sánchez-Pérez EA. The Future of Higher Education: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in AI-Driven Lifelong Learning in Peru. Information. 2025; 16(3):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030224

Chicago/Turabian StyleLara-Navarra, Pablo, Antonia Ferrer-Sapena, Eduardo Ismodes-Cascón, Carlos Fosca-Pastor, and Enrique A. Sánchez-Pérez. 2025. "The Future of Higher Education: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in AI-Driven Lifelong Learning in Peru" Information 16, no. 3: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030224

APA StyleLara-Navarra, P., Ferrer-Sapena, A., Ismodes-Cascón, E., Fosca-Pastor, C., & Sánchez-Pérez, E. A. (2025). The Future of Higher Education: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities in AI-Driven Lifelong Learning in Peru. Information, 16(3), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030224