AHP-Based Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services in Academic Libraries Under Digital Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on the Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services

2.2. Transformation of Discipline-Specific Information Services Driven by Digital and Intelligent Technologies

2.3. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in Information Service Quality Evaluation

2.4. Summary

3. Construction of the Discipline-Specific Information Service Quality Evaluation Indicator System

3.1. Research Process

- (1)

- Selection and Structuring of Evaluation Indicators: To overcome the limitations of a single evaluation method and address the challenges of operability and measurability in evaluating subjective indicators, this study follows the principles of objectivity, systematicity, scientific rigor, applicability, and operability. A comprehensive approach integrating a literature review and expert interviews is employed to select, refine, validate, revise, and finalize the evaluation indicators for discipline-specific information services in academic libraries. This ensures that the evaluation indicator system is both scientifically robust and widely applicable across different contexts. The selected indicators are further categorized into specific sub-indicators, covering various aspects of service quality, and structured into a hierarchical model.

- (2)

- AHP-Based Weight Allocation: The AHP method is applied to assign weights to both the criterion-level indicators and sub-indicators. Expert judgments on the relative importance of these criteria are used to construct a pairwise comparison matrix, from which the weight of each criterion is derived. The AHP process consists of the following five steps:

- Conceptualizing the research problem and decomposing it into multiple interrelated components, forming a multilevel hierarchical structure: In this study, the evaluation of discipline-specific information service quality in academic libraries is structured into a three-tier hierarchical model: the goal level, which represents the overall evaluation of discipline-specific information service quality; the criterion level, encompassing six core dimensions; and the alternative level, consisting of 15 specific evaluation indicators.

- Using elements from a higher level as evaluation criteria, conducting pairwise comparisons of lower-level elements to establish a judgment matrix: In this study, the expert interview method was employed, involving 12 experts who conducted pairwise comparisons of the six dimensions and their 15 sub-indicators to construct the judgment matrix.

- Based on the judgment matrix, calculating the relative weights of each element with respect to its higher-level criterion: In this study, the eigenvector method was employed to calculate the relative weights of the judgment matrix, thereby determining the final weight of each indicator.

- Performing a consistency test on the judgment matrix, ensuring that the consistency ratio (CR) is below 0.10, which indicates an acceptable level of consistency in weight allocation.

- Calculating the composite weights of all elements within the hierarchy to generate the final evaluation model, providing a foundation for subsequent comprehensive evaluation.

- (3)

- Comprehensive Evaluation and Validation: The hierarchical structure analysis of AHP provides the weight foundation, while FCE further compensates for AHP’s limitations in capturing users’ subjective evaluations, ensuring that the evaluation system integrates both a structured decision-making logic and a user-centered assessment approach. The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (FCE) method, based on fuzzy mathematics, is adopted due to its advantages in handling ambiguous, difficult-to-quantify factors and providing clear, structured results [39]. The FCE method is utilized to quantify users’ qualitative evaluations of each indicator, thereby generating an objective and accurate assessment score for the evaluation system.

3.2. Empirical Analysis

3.2.1. Preliminary Selection of Dimension Indicators Based on the Literature Review

3.2.2. Selection of Dimensions and Indicators Based on Expert Interviews

- Selection and Composition of Research Experts

- 2.

- Implementation of Expert Interviews

- Scientific Rigor and Applicability of the Dimensions and Indicators: Do the six proposed dimensions comprehensively capture the core aspects of discipline-specific information service quality?

- Technology-Driven and Intelligent Services: How do artificial intelligence, big data, and knowledge graphs impact discipline-specific information service quality in the digital-intelligence era? Which technologies hold the greatest potential for the future development of discipline-specific information services?

- Practical Value of the Dimensions and Indicators: Does the evaluation system align with the practical needs of discipline-specific information services in university libraries?

- 3.

- Analysis of Expert Interview Results

3.3. Selection of Model Dimensions and Indicators

3.4. Determination of Indicator Weights in the Evaluation System Based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

Detailed Process Description

- Establishing the Hierarchical Structure Model (Figure 2):

- 2.

- Expert Interviews and Scoring

- 3.

- Scoring Scale and Data Aggregation

- 4.

- Software Analysis and Consistency Testing

4. Empirical Validation of the Quality Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services in Academic Libraries

4.1. Sample Selection, Data Sources, and Processing

4.2. Evaluation Process

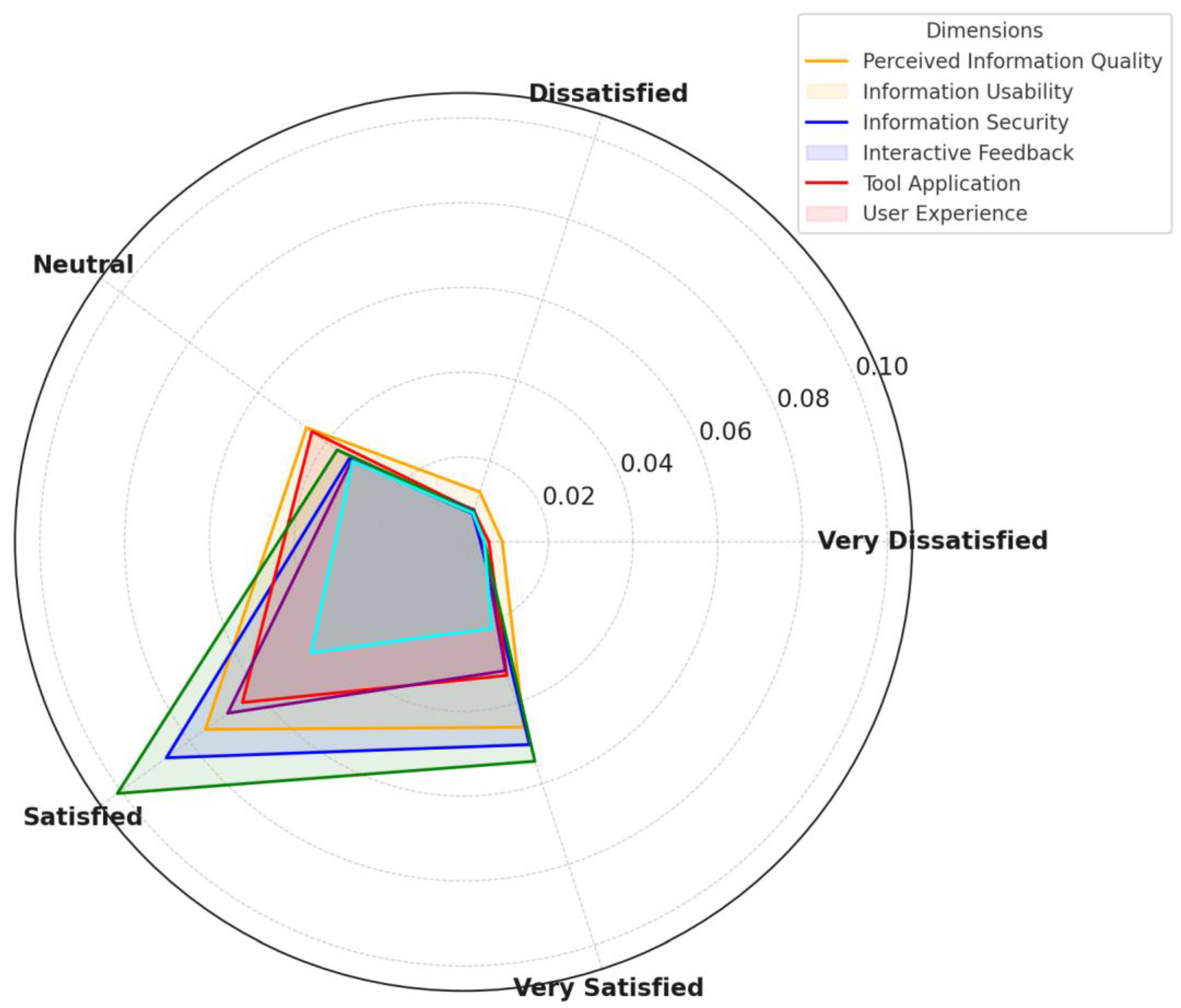

4.3. Results Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Survey Questionnaire: Survey on the Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services at Tsinghua University Library

- Section 1: Information Quality

- Information Relevance

- How would you evaluate the relevance of the library’s discipline-specific information to your research and teaching needs? Do you find the library’s resources closely aligned with your discipline and research focus?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Information Accuracy

- How would you rate the accuracy and reliability of the library’s discipline-specific information? Do you find the retrieved documents and data credible and trustworthy?

- (1)Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Information Diversity

- How would you evaluate the richness and diversity of the discipline-specific resources provided by the library? Are you satisfied with the library’s coverage of various types of literature and interdisciplinary resources?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Section 2: Information Usability

- Ease of System Operation

- How would you rate the user experience of the library’s discipline-specific information service platform, including search, browsing, and download functions? Is the system interface intuitive and easy to use?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Personalized Services

- How would you evaluate the library’s ability to provide personalized information recommendations and customized services based on your preferences? Do you find the recommended content relevant to your needs?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Section 3: Information Security

- User Privacy Protection

- How satisfied are you with the library’s measures to protect your privacy and ensure data security? Do you trust the library to handle your personal and academic data responsibly?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- System Reliability

- How would you evaluate the stability and reliability of the library’s discipline-specific information service system? Does the system frequently encounter issues or become inaccessible?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Section 4: Interaction Feedback

- Efficiency of Communication and Feedback

- How would you rate the speed and efficiency of the library in responding to your inquiries, suggestions, or feedback? Do you find the service responses timely?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Organization and Collaboration

- How effective do you find the library’s efforts to build discipline-specific communities or virtual collaboration platforms? Do these platforms facilitate communication and collaboration among faculties, students, and library staff?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Section 5: Tools and Technology Application

- Tool Availability

- How would you evaluate the practicality of the information analysis tools and related training services provided by the library? Do these tools help you better utilize discipline-specific information?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- AI-Driven Features

- How would you evaluate the library’s use of AI, big data, and other technologies to enable intelligent recommendations, automated classification, and other features? Do you believe these features enhance service quality and efficiency?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Discipline Data Management

- How satisfied are you with the library’s support for the collection, storage, sharing, and reuse of discipline-specific research data? Are you satisfied with the quality and usability of these services?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Section 6: User Experience

- Satisfaction and Trust

- Overall, how satisfied are you with the library’s discipline-specific information services? How much do you trust the library’s brand and service quality?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Support for Learning and Research

- How would you rate the contribution of the library’s discipline-specific information services to your learning and research activities? Have the services effectively supported your academic work?

- (1) Very Dissatisfied

- (2) Dissatisfied

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Satisfied

- (5) Very Satisfied

- Willingness for Continued Use

- Based on your experience, would you be willing to continue using the library’s discipline-specific information services and recommend them to others?

- (1) Very Unwilling

- (2) Unwilling

- (3) Neutral

- (4) Willing

- (5) Very Willing

References

- Tam, L.W.H.; Robertson, A.C. Managing change: Libraries and information services in the digital age. Libr. Manag. 2002, 23, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Helena, V.; Leonor Gaspar, P.; Paula, O. Revisiting digital libraries quality: A multiple item scale approach. Perform. Meas. Metr. 2011, 12, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Town, J.S. Value, impact, and the transcendent library: Progress and pressures in performance measurement and evaluation. Libr. Q. 2011, 81, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.C. A Mixed-Method Approach to the Identification and Measurement of Academic Library Service Quality Constructs: LibQUAL+TM. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adarkwah, M.A.; Okagbue, E.F.; Oladipo, O.A.; Mekonen, Y.K.; Anulika, A.G.; Nchekwubemchukwu, I.S.; Okafor, M.U.; Chineta, O.M.; Muhideen, S.; Islam, A.A. Exploring the Transformative Journey of Academic Libraries in Africa before and after COVID-19 and in the Generative AI Era. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2024, 50, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, W. Are academic libraries changing fast enough? Bibl. Forsch. Prax. 2018, 42, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D. Beyond Providing Information: An Analysis on the Perceived Service Quality, Satisfaction, and Loyalty of Public Library Customers. Libri 2002, 70, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, K.; Diljit, S. Modelling web-based library service quality. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2012, 34, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S. A conceptual framework for the holistic measurement and cumulative evaluation of library services. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2004, 41, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. On user studies and information needs. J. Doc. 2006, 62, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, L.; Stock, W.G. The Information Service Evaluation (ISE) model. Webology 2014, 11, 1–20. Available online: http://www.webology.org/2014/v11n1/a115.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Guttsman, W.L. Subject Specialisation in Academic Libraries: Some preliminary observations on role conflict and organizational stress. J. Librariansh. 1973, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishar NI, M.; Masodi, M.S. Students’ perception towards quality library service using Rasch Measurement Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovation Management and Technology Research, Malacca, Malaysia, 21–22 May 2012; pp. 668–672. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran, K. Service quality and customer satisfaction in academic libraries: Perspectives from a Malaysian university. Libr. Rev. 2010, 59, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettinger, W.J.; Lee, C.C. Perceived service quality and user satisfaction with the information services function. Decis. Sci. 2010, 25, 737–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, F.J.; López-Gijón, J.; Martínez, M.A.; Morente-Molinera, J.A.; Herrera Vied-ma, E.A. fuzzy linguistic extended LibQUAL+ model to assess service quality in academic libraries. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2017, 16, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, P. Measuring Library Performance: Principles and Techniques; Facet Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Loiacono, E.T.; Watson, R.T.; Goodhue, D.L. WebQual: An Instrument for Consumer Evaluation of Web Sites. Int. Electron. Commer. 2007, 11, 51–87. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27751221 (accessed on 16 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hernon, P.; Calvert, P. E-Service quality in libraries: Exploring its features and dimensions. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2005, 27, 377–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinfield, S. The changing role of subject librarians in academic libraries. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2001, 33, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, D.; Wallace, A. Intentional informationists: Re-envisioning information literacy and re-designing instructional programs around faculty librarians’ strengths as campus connectors, information professionals, and course designers. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2013, 39, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.; Eng, S. What students want: Generation Y and the changing function of the academic library. Portal Libr. Acad. 2005, 5, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Khan, S.A.; Iqbal, A. Effects of big data analytics on university libraries: A systematic literature review of impact factor articles. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, L. Generative AI and Libraries: Seven Contexts. 29 July 2024. LorcanDempsey.net. Available online: https://www.lorcandempsey.net/generative-ai-and-libraries-7-contexts/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Smith, H.J.; Milberg, S.J.; Burke, S.J. Information privacy: Measuring individuals’ concerns about organizational practices. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. Problems and changes in digital libraries in the age of big data from the perspective of user services. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2018, 45, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Fan, L. Performance evaluation about development and utilization of public information resource based on Analytic Hierarchy Process. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Management and Service Science, Wuhan, China, 12–14 August 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. Evaluation of e-commerce service quality using the analytic hierarchy process. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communication and 2010 Asia-Pacific Conference on Information Technology and Ocean Engineering, Macao, China, 30–31 January 2010; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddershede, A.M.; Carrasco, R.; Barham, E. Analytic hierarchy process model for evaluating a health service information technology network. Health Inform. J. 2007, 13, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Villacreses, G.; Jijón, D.; Nicolalde, J.F.; Martínez-Gómez, J.; Betancourt, F. Multicriteria decision analysis of suitable location for wind and photovoltaic power plants on the Galápagos Islands. Energies 2023, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.K.; Wang, S.-C. The Critical Factors of Success for Information Service Industry in Developing International Market: Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, E.W.T.; Chan, E.W.C. Evaluation of Knowledge Management Tools Using AHP. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2005, 29, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S.; Hsieh, Y.-C. Applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process for Investigating Key Indicators of Responsible Innovation in the Taiwan Software Service Industry. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. Redirection in Academic Library Management; Library Association: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Landøy, A. Using statistics for quality management in the library. In New Trends in Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries: Proceedings of the 2nd Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries International Conference, Chania, Crete, Greece 2012, 25–28 May 2010; Katsirikou, A., Skiadas, C., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.P. Determining the reliability and validity of service quality scores in a public library context: A confirmatory approach. Adv. Libr. Adm. Organ. 2008, 26, 317–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Abawajy, J.H. Digital library service quality assessment model. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Wei, S.; Yu, Y. The Framework of Technical Evaluation Indicators for Constructing Low-Carbon Communities in China. Buildings 2021, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Malhotra, A. E-S-QUAL: A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. J. Serv. Research 2005, 7, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, S.; Pitt, L. SERVQUAL as a measuring instrument for service provider gaps in business schools. Manag. Res. News 1992, 15, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Malhotra, A. Conceptual Framework for Understanding E-Service Quality: Implications for Future Research and Managerial Practice; working paper, Report No. 00-115; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine de Gruyter: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Multicriteria Decision Making: The Analytic Hierarchy Process; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.J.; Borycz, J. Integrating large language models and generative artificial intelligence tools into information literacy instruction. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2024, 50, 102899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Definition | Representative Literature | Referenced Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Information Quality | Evaluates the relevance, accuracy, timeliness, reliability, comprehensiveness, and diversity of discipline-specific information provided by the library. | Parasuraman [40] Loiacono [19] | E-SERVQUAL |

| Information Usability | Assesses the convenience of accessing and utilizing discipline-specific information services, including system simplicity, search tool usability, and ease of information retrieval. | Aladwani, A. M. [5] | WebQual |

| Information Security | Evaluates the degree of confidentiality protection in discipline-specific information services, including user privacy protection and data security. | Smith et al. [28] | E-SERVQUAL |

| Interactive Feedback | Measures the library’s capability to facilitate communication and feedback between users, as well as between users and the service platform or providers. | Rigotti et al. [41] | LibQUAL+TM E-SERVQUAL WebQual |

| Tool Application | Assesses the types and quality of tools provided by academic libraries for viewing, analyzing, and utilizing information services. | Loiacono [19] | WebQual |

| User Experience | Reflects users’ overall perception and satisfaction regarding personalized discipline-specific information services in academic libraries. | Zeithamal et al. [42] | WebQual SERVQUAL |

| Serial Number of the Expert | Type of Expert | Research/Practical Background |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | University Library Discipline-Specific Information Service Expert | Background in history and library science; works in a university discipline-specific information service department, responsible for academic information resource management, subject-specific information organization, and retrieval. |

| 2 | Background in computer science; responsible for university technological innovation, research commercialization, intellectual property information management consulting, and smart library system development. | |

| 3 | Background in history and information science; responsible for academic information service consulting and faculty–student information literacy education. | |

| 4 | Background in engineering; responsible for intelligence analysis and consulting services related to key disciplines in the university. | |

| 5 | Background in library and information science; responsible for graduate education information services and research data management. | |

| 6 | Background in library science; specializes in academic information resource sharing and inter-institutional collaboration, previously participated in academic library consortium projects. | |

| 7 | Background in information science and data analysis; responsible for academic information service consulting, strategy report writing, and related tasks. | |

| 8 | Background in information science; responsible for university digital resource procurement, evaluation, and research data management and mining. | |

| 9 | Library and Information Science Researcher | PhD, professor, and doctoral supervisor; research focuses on discipline-specific information resource development and user information behavior analysis; has led multiple national research projects. |

| 10 | PhD, professor; specializes in e-service quality and user behavior psychology; has been invited to participate in government digital service quality evaluations. | |

| 11 | PhD, professor; responsible for master’s and doctoral courses in information management; primary research areas include artificial intelligence and information ethics. | |

| 12 | PhD, associate professor, and master’s supervisor; research focuses on artificial intelligence and academic innovation, as well as university education management. |

| Question Categories | Summary of Interview Results |

|---|---|

| Quality Elements of Discipline-Specific Information Content | 1. Authenticity, accuracy, and applicability of information are crucial. 2. Timeliness of information ensures users access the latest discipline-specific knowledge. 3. Diversified types of information, including books, articles, research reports, and databases. 4. Originality of information supports the innovative development of disciplines. 5. Discipline-specific information should cover different research levels and directions. |

| Coverage Elements of Discipline-Specific Information | 1. Provide comprehensive discipline-specific information covering various academic fields. 2. Supply diverse types of information, such as books, journals, databases, and electronic resources. 3. Introduce intelligent recommendation algorithms to identify personalized user needs and offer dynamic updates. |

| Acquisition and Navigation of Discipline-Specific Information | 1. Easy-to-use retrieval systems with convenient keyword search, categorized search, and data download options. 2. Scientifically designed and intelligent navigation systems support fast resource location via voice or natural language. 3. Structured presentation of information for ease of understanding and application. 4. Provide necessary user guides and support for efficient system usage. |

| User Feedback and Interaction in Discipline-Specific Information Services | 1. Establish user communities to encourage communication and collaboration among users. 2. Conduct regular user satisfaction surveys to understand changing user needs. 3. Develop evaluation and feedback mechanisms for service quality. 4. Facilitate user feedback through online Q&A, intelligent chatbots, and real-time support to improve efficiency and satisfaction. |

| Tools and Application Support for Discipline-Specific Information Analysis | 1. Provide convenient online tools, such as data analysis and reference management tools. 2. Ensure usability of research tools to meet diverse user needs with technical, teaching, and training support. 3. Guarantee compatibility and stability of research tools. |

| User Experience in Discipline-Specific Information Services | 1. Offer diverse service formats, such as hybrid online and offline services, to meet varying user needs. 2. Monitor user behavior trends to provide advanced and responsive services. |

| Dimension | Indicator | Indicator Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Information Quality | Information Relevance | The degree to which the discipline-specific information provided by the library matches users’ research and teaching needs, including alignment with topics, fields, and research trends. |

| Information Accuracy | Authenticity and reliability, such as the accuracy of document resources, credibility of discipline-specific data sources, and correctness of discipline knowledge graphs. | |

| Information Diversity | Richness of resource types (e.g., papers, conferences, patents, standards, experimental data) and coverage of interdisciplinary and emerging fields. | |

| Information Usability | Ease of System Operation | The platform and resource repository offer an intuitive, convenient, and efficient user experience for searching, browsing, and downloading, covering interface design, navigation structure, and search functionality layout. |

| Personalized Services | Discipline-specific information services provide recommendations based on user preferences or behavior data, such as customized topic subscriptions and focused discipline sections, offering tailored online and offline integrated services. | |

| Information Security | User Privacy Protection | Security guarantees in information services, including authorized access, technical standards, and protection of confidential research data. |

| System Reliability | The stability of the discipline-specific information service platform, such as ensuring data backup and emergency response plans. | |

| Interactive Feedback | Efficiency of Communication and Feedback | The speed and efficiency of responses to user inquiries and suggestions by librarians or service platforms, including online consultations, offline appointments, and real-time communication tools. |

| Organization and Collaboration | Building discipline communities or virtual collaboration platforms to support ongoing communication, resource sharing, and co-creation among faculties, research teams, and librarians. | |

| Tool Application | Tool Availability | Information analysis tools and training services provided by libraries to facilitate the use of discipline-specific information and the presentation of research outcomes. |

| AI-Driven Features | Capabilities enabled by AI, big data, or knowledge graphs, such as intelligent recommendations, automatic classification, semantic search, trend prediction, and digital literacy skills. | |

| Discipline Data Management | Support for the collection, storage, sharing, and reuse of discipline-specific research data, such as data repositories, metadata management, data visualization, and collaborative analysis. | |

| User Experience | Satisfaction and Trust | Users’ overall satisfaction with discipline-specific information services and their trust in the library’s brand and the professional competence of librarians. |

| Support for Learning and Research | The extent to which services contribute to users’ academic activities, including support for course instruction, thesis writing, and research project progress. | |

| Willingness for Continued Use | The likelihood that users will continue or repeatedly use discipline-specific information services and recommend them to others after their experience. |

| Scale | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Two factors are of equal importance. |

| 3 | Indicates that one factor is slightly more important than the other. |

| 5 | Indicates that one factor is significantly more important than the other. |

| 7 | Indicates that one factor is strongly more important than the other. |

| 9 | Indicates that one factor is extremely more important than the other. |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate values between two adjacent judgments to reflect a more precise level of importance. |

| Reciprocal () | If factor is times more important than factor , then factor is times as important as factor . |

| Relative Importance | Perceived Information Quality | Information Usability | Information Security | Interactive Feedback | Tool Application | User Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Information Quality | 1.000 | 1.15 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 0.91 | 2.02 |

| Information Usability | 0.87 | 1.000 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.82 | 1.86 |

| Information Security | 0.77 | 0.83 | 1.000 | 1.02 | 0.68 | 1.54 |

| Interactive Feedback | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 1.000 | 0.69 | 1.48 |

| Tool Application | 1.10 | 1.22 | 1.47 | 1.45 | 1.000 | 2.14 |

| User Experience | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 1.000 |

| Maximum Eigenvalue | CI Value | RI Value | CR Value | Consistency Check Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.0088 | 0.0018 | 1.260 | 0.0014 | Passed |

| Perceived Information Quality Indicators | Information Relevance (C1) | Information Accuracy (C2) | Information Diversity (C3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 0.10010 | 0.06006 | 0.04004 |

| Information Usability Indicators | System Usability (C4) | Personalized Services (C5) | |

| Weight | 0.09911 | 0.08109 | |

| Information Security Indicators | User Privacy Protection (C6) | System Reliability (C7) | |

| Weight | 0.09090 | 0.06060 | |

| Interactive Feedback Indicators | Response Efficiency (C8) | Collaboration and Engagement (C9) | |

| Weight | 0.09724 | 0.05236 | |

| Tool Application Indicators | Tool Availability (C10) | AI-Driven Features (C11) | Discipline Data Management (C12) |

| Weight | 0.08736 | 0.07644 | 0.05460 |

| User Experience Indicators | Satisfaction and Trust (C13) | Learning and Research Support (C14) | Continued Usage Intent (C15) |

| Weight | 0.04509 | 0.03507 | 0.02004 |

| Dimension | Dimension Weight | Indicator | Relative Weight Within Dimension | Final Indicator Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Information Quality Indicators | 0.2002 | Information Relevance (C1) | 0.50 | 0.1001 |

| Information Accuracy (C2) | 0.30 | 0.0600 | ||

| Information Diversity (C3) | 0.20 | 0.0404 | ||

| Information Usability Indicators | 0.1802 | System Usability (C4) | 0.55 | 0.0991 |

| Personalized Services (C5) | 0.45 | 0.0810 | ||

| Information Security Indicators | 0.1515 | User Privacy Protection (C6) | 0.60 | 0.0909 |

| System Reliability (C7) | 0.40 | 0.0606 | ||

| Interactive Feedback Indicators | 0.1496 | Response Efficiency (C8) | 0.65 | 0.0972 |

| Collaboration and Engagement (C9) | 0.35 | 0.0523 | ||

| Tool Application Indicators | 0.2184 | Tool Availability (C10) | 0.40 | 0.0874 |

| AI-Driven Features (C11) | 0.35 | 0.0764 | ||

| Discipline Data Management (C12) | 0.25 | 0.0546 | ||

| User Experience Indicators | 0.1002 | Satisfaction and Trust (C13) | 0.45 | 0.0451 |

| Learning and Research Support (C14) | 0.35 | 0.0351 | ||

| Continued Usage Intent (C15) | 0.20 | 0.0200 |

| Indicator | Very Dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Neutral | Satisfied | Very Satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Relevance (C1) | 0.0357 | 0.0536 | 0.2143 | 0.4286 | 0.2679 |

| Information Accuracy (C2) | 0.0517 | 0.0862 | 0.2414 | 0.3448 | 0.2069 |

| Information Diversity (C3) | 0.061 | 0.0458 | 0.2441 | 0.2905 | 0.1678 |

| System Usability (C4) | 0.0185 | 0.037 | 0.1852 | 0.5185 | 0.3148 |

| Personalized Services (C5) | 0.027 | 0.0405 | 0.1851 | 0.4363 | 0.2361 |

| User Privacy Protection (C6) | 0.0469 | 0.0586 | 0.2734 | 0.4297 | 0.1914 |

| System Reliability (C7) | 0.028 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.26 |

| Response Efficiency (C8) | 0.0296 | 0.0556 | 0.2037 | 0.4815 | 0.2407 |

| Collaboration and Engagement (C9) | 0.0315 | 0.0489 | 0.2449 | 0.4206 | 0.1641 |

| Tool Availability (C10) | 0.0156 | 0.025 | 0.125 | 0.4375 | 0.25 |

| AI-Driven Features (C11) | 0.0259 | 0.0444 | 0.1852 | 0.5 | 0.2593 |

| Discipline Data Management (C12) | 0.0288 | 0.036 | 0.2162 | 0.4505 | 0.2342 |

| Satisfaction and Trust (C13) | 0.0431 | 0.0647 | 0.3026 | 0.4741 | 0.2138 |

| Learning and Research Support (C14) | 0.048 | 0.072 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.22 |

| Continued Usage Intent (C15) | 0.0625 | 0.0833 | 0.375 | 0.4167 | 0.2083 |

| Very Dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Neutral | Satisfied | Very Satisfied | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Information Quality | 0.00913997 | 0.01238768 | 0.04579707 | 0.07532706 | 0.04600991 |

| Information Usability | 0.00402035 | 0.0069472 | 0.03334642 | 0.08672365 | 0.05032078 |

| Information Security | 0.00596001 | 0.00775074 | 0.04424406 | 0.06451173 | 0.03315426 |

| Interactive Feedback | 0.00452457 | 0.00796179 | 0.03260791 | 0.06879918 | 0.03197847 |

| Tool Application | 0.00491468 | 0.00754276 | 0.0368788 | 0.1010348 | 0.05444784 |

| User Experience | 0.00487861 | 0.00711117 | 0.03237926 | 0.04445791 | 0.02153038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. AHP-Based Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services in Academic Libraries Under Digital Intelligence. Information 2025, 16, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030245

Zhang S, Zhang T, Wang X. AHP-Based Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services in Academic Libraries Under Digital Intelligence. Information. 2025; 16(3):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030245

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Simeng, Tao Zhang, and Xi Wang. 2025. "AHP-Based Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services in Academic Libraries Under Digital Intelligence" Information 16, no. 3: 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030245

APA StyleZhang, S., Zhang, T., & Wang, X. (2025). AHP-Based Evaluation of Discipline-Specific Information Services in Academic Libraries Under Digital Intelligence. Information, 16(3), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16030245