A Mixed-Method Approach for Domain Analysis in Interdisciplinary Fields Using Bibliometrics: The Case of Global Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- Enhance domain analysis knowledge by empirically applying a mixed-method approach to GS, an interdisciplinary field of knowledge.

- −

- Nourish the current state-of-the-art, which is characterized by studies in which bibliometrics is generally used as the single analysis method, generally not for KO. Many studies involving bibliometrics, under the label of “domain analysis”, are analyses of a field that considers only bibliometric metrics, which serve purposes different from those of KO.

- −

- Provide GS scholars and information centers with additional terminology corresponding to non-controlled vocabularies. Currently, controlled vocabularies cannot be updated at the same pace as knowledge production, a problem faced by current thesauruses on GS and related fields.

- −

- The understanding of an emergent field not yet recognized in current classifications in libraries, bibliographical databases, or supranational organizations, e.g., OCDE or UNESCO.

1.1. Domain Analysis and Bibliometrics

1.2. Bibliometrics, Domain Analysis and KO

1.3. Global Studies and the Interdisciplinary Challenge

1.4. Interdisciplinary Fields and KO

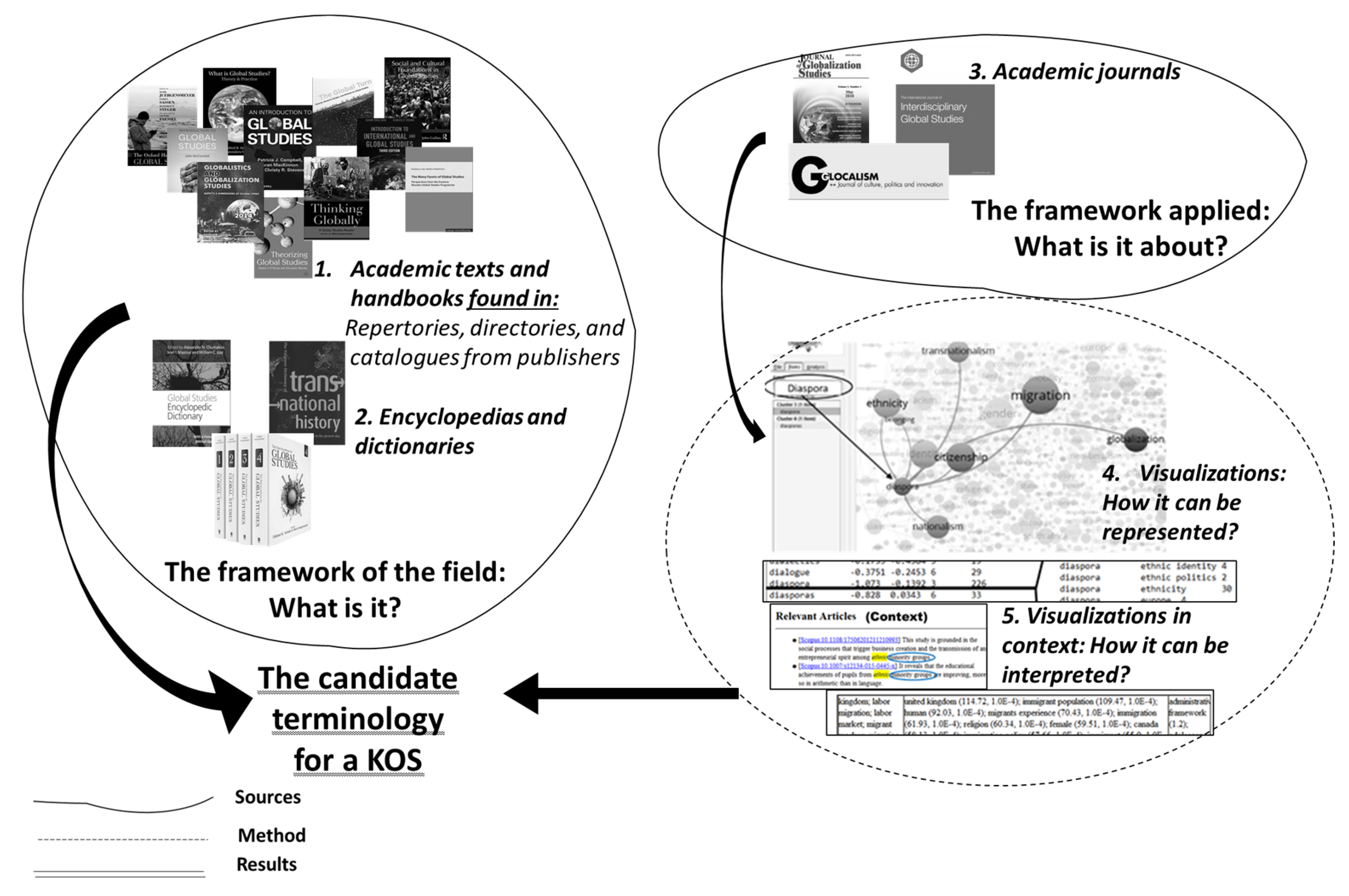

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Understanding GS Through Selected Theoretical Books

- Introductory discussions and theoretical chapters about GS: Identification of content about the definition of the field, its main characteristics, theories, and related fields.

- Main chapters with study cases: Identification of the main topics used by scholars as examples of research subjects in GS.

- References: Manual identification of the main disciplines included in the referenced sources.

- Appendixes: Lists of bibliographical material that provide general information on academic journal titles and GS websites.

2.2. GS and Its Terminology in Reference Sources (Method I)

- −

- Generate group categories that will help to understand the terminology of the GS domain community.

- −

- Be able to identify the key concepts related to the GS field to improve the thematic criteria in choosing the sample (academic journals).

- −

- Become familiar with the GS terminology to compare some results among visualizations and analyze results.

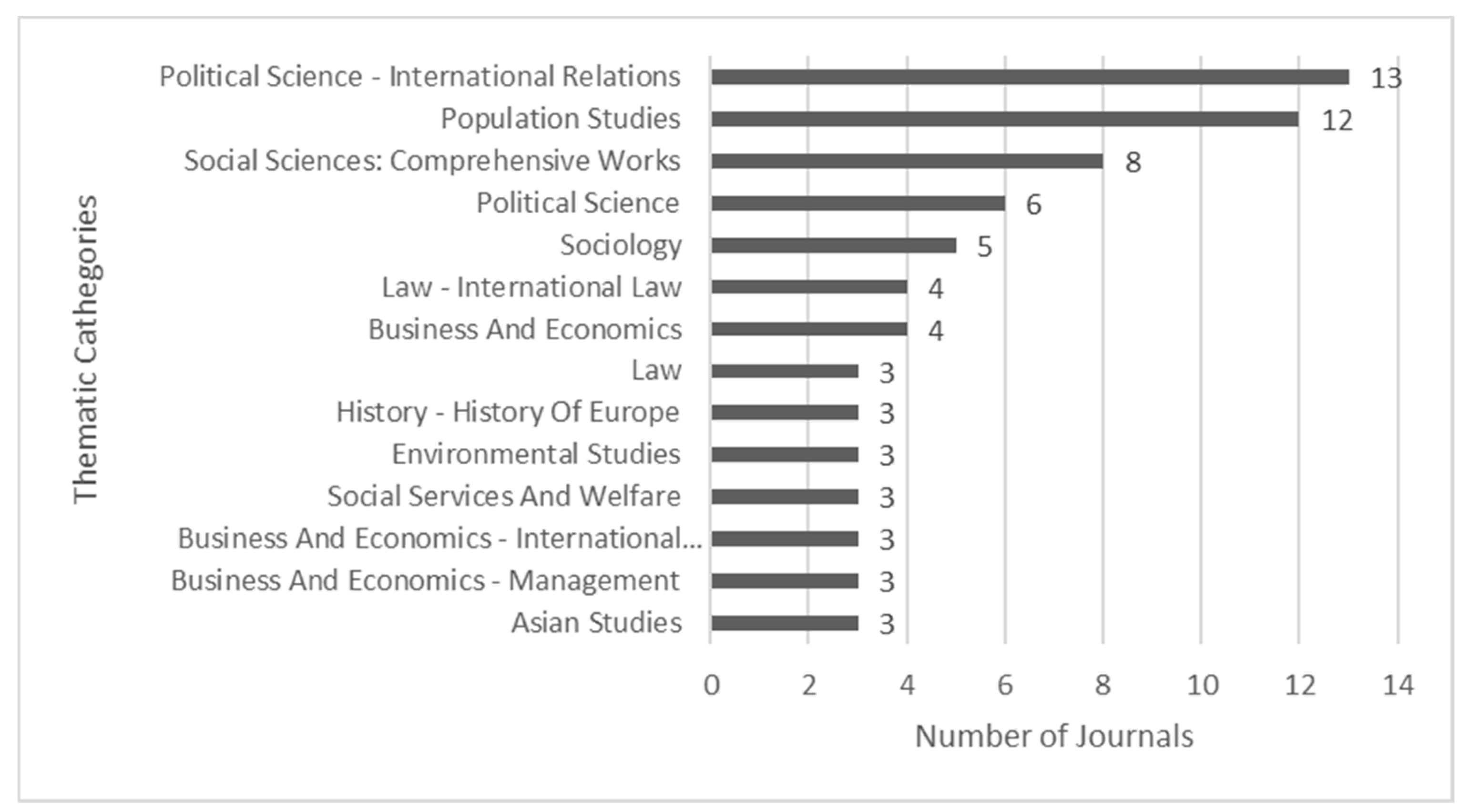

2.3. Global Studies and Co-Occurrence Bibliometric Analysis (Method II)

- −

- The serial directory UlrichWeb and

- −

- Recommended literature on the Websites of GS academic programs

2.4. The Two Complementary Methods for Domain Analysis

2.5. The Terminology and the Classification System ILC

3. Results

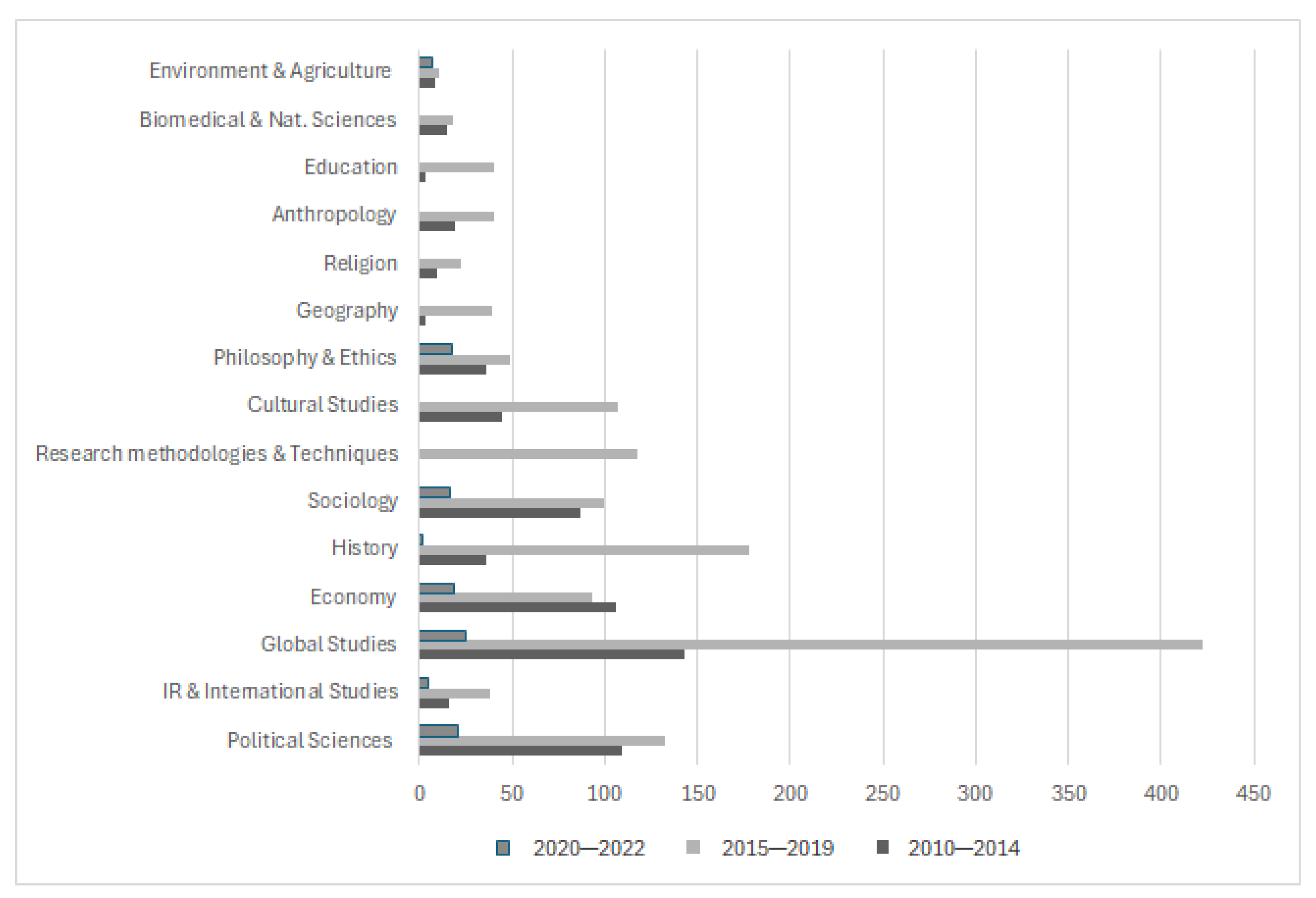

3.1. Main Disciplines and Subject Categories in Books

Global Studies Main Topics in Three Selected Reference Sources

- Generate group categories that will help us understand the terminology of the GS domain community.

- −

- Be able to identify the key concepts related to the GS field to improve the thematic criteria when choosing the sample of academic journal titles

- −

- Become familiar with the GS terminology, facilitating the selection of the phenomena included in the ILC case examples for the GS field.

- Communications and technology

- History, culture, and society

- Demography, environment, and resources

- Education and knowledge

- Economy and trade

- Global order and politics

- Law and regulations

- Religion and ideologies

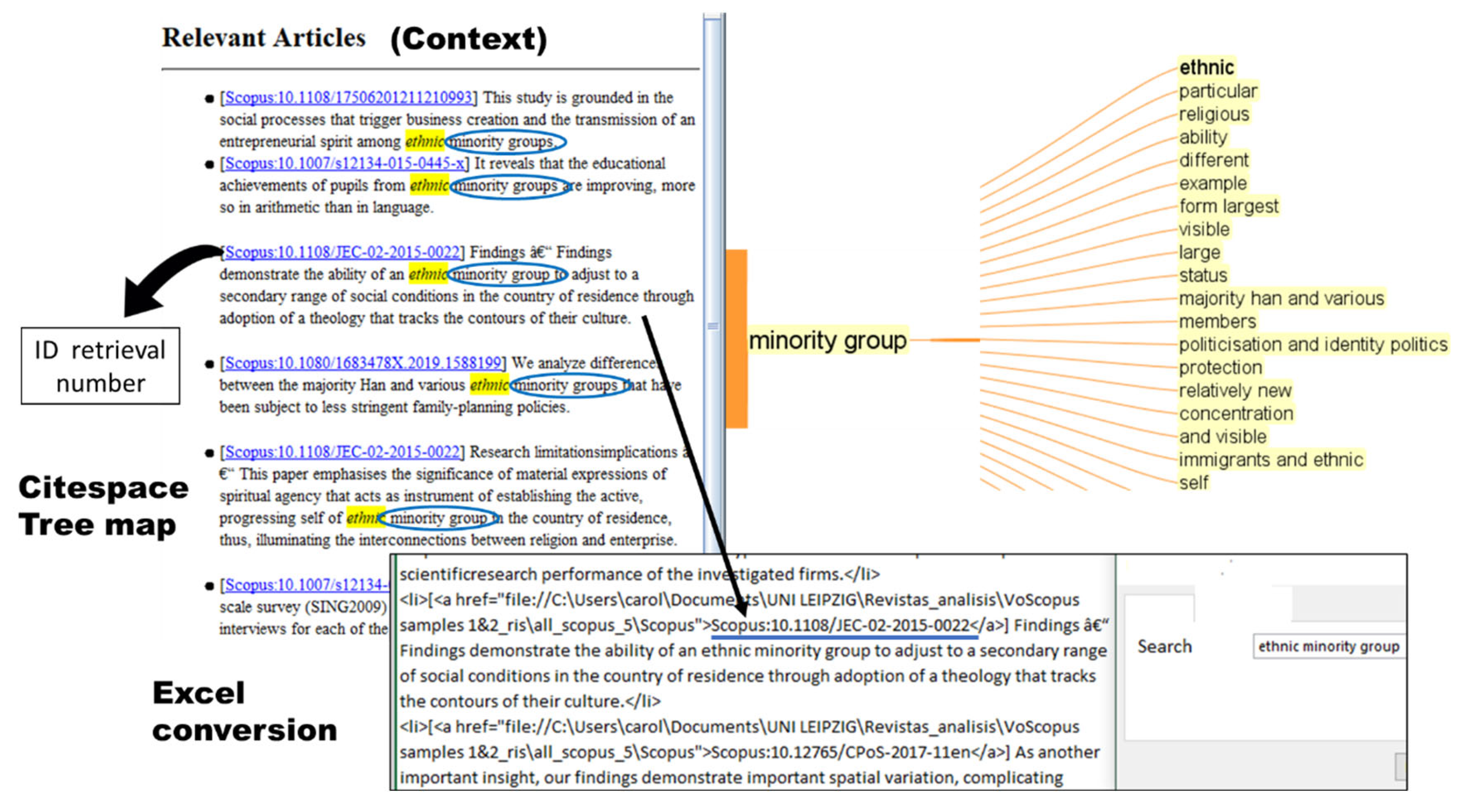

3.2. Co-Occurred Terms and Keywords in GS Journal Titles and the ILC Classification

4. Discussion

4.1. The Contribution of Various Sources for the Characterization of the Global Studies Field

The Main Characteristics of GS Are Based on the Studies’ Results

4.2. The Mixed-Methods Approach and Its Contribution to LIS Using Bibliometrics

- A selection of sources that did not rely on pre-defined categories but in the manual selection of them based on content revision

- The use of two complementary bibliometric software programs

- The analysis of terminological reference sources based on a non-disciplinary categorization of entries (Own proposed categories)

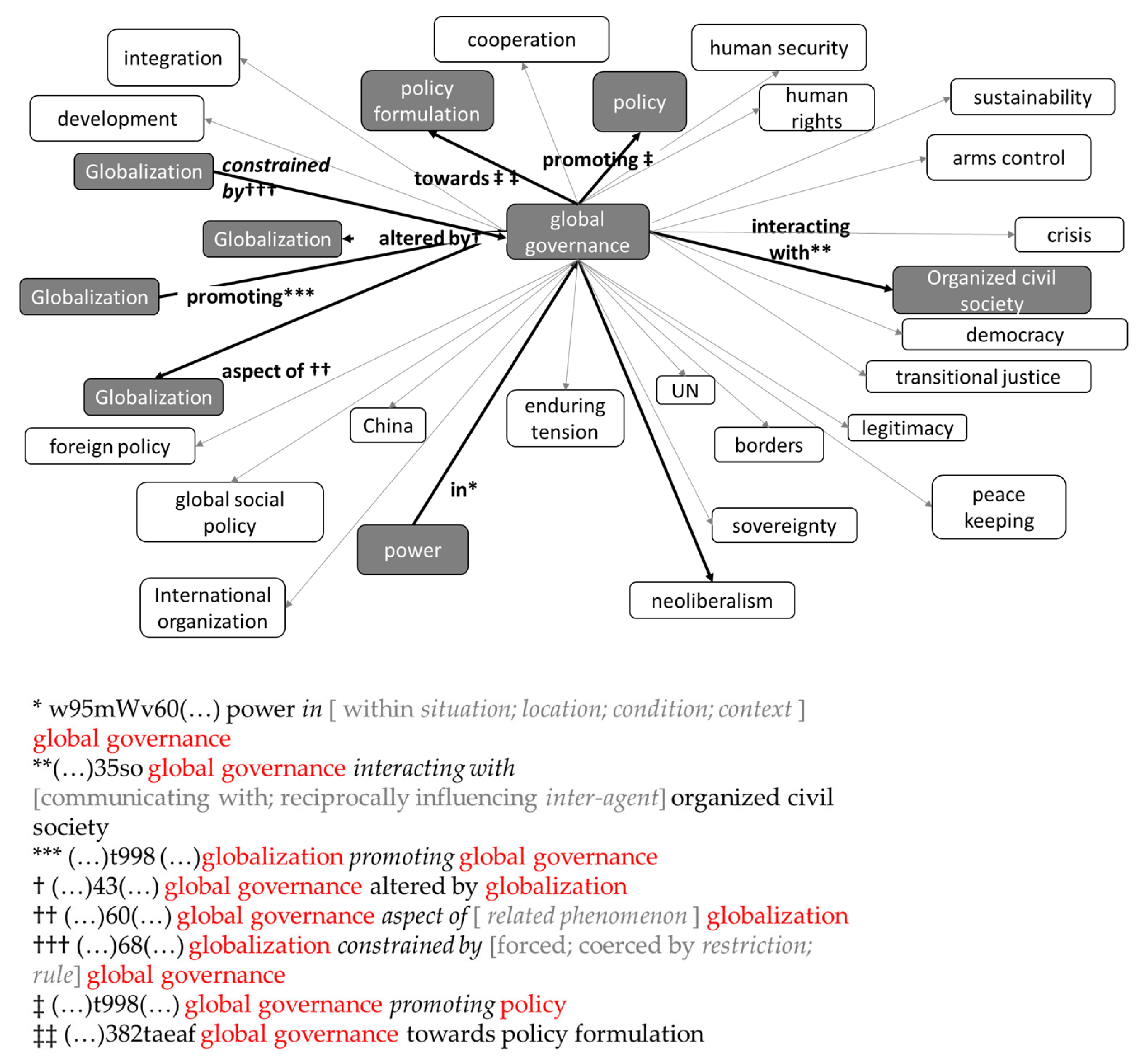

- The analysis of sources in context, where the content of articles with high co-occurrence of specific terms and keywords provided a list of main topics that GS scholars are interested in (Global governance, as selected as an example in Figure 9).

- The application of co-occurred phenomena into a non-hierarchical classification of sciences.

4.3. What Does the Process of Content Analysis Say About the Field, and What Is Its Contribution to the ILC Classification?

4.4. Limitations of the Study and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hjørland, B.; Albrechtsen, H. Toward a New Horizon in Information Science: Domain-analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1995, 46, 400–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjørland, B. Domain Analysis in Information Science: Eleven Approaches-Traditional as Well as Innovative. J. Doc. 2002, 58, 422–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiraglia, R.P. Domain Analysis for Knowledge Organization: Tools for Ontology Extraction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennis, J. Two Axes of Domains for Domain Analysis. Knowl. Organ. 2003, 30, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina Gutierres Castanha, R.; Cláudia Cabrini Grácio, M.; Cristina Gutierres, R.; Cláudia Cabrini, M. Bibliometrics Contribution to the Metatheoretical and Domain Analysis Studies. Knowl. Organ. 2014, 41, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjørland, B. Domain Analysis. Knowl. Organ. 2017, 44, 436–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.B.; Wahlrab, A. What Is Global Studies?: Theory & Practice; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Juergensmeyer, M.; Faessel, V.; Steger, M.B.; Sassen, S. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Global Studies; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.B.; Battersby, P.; Siracusa, J.M. The SAGE Handbook of Globalization; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostak, R.; Gnoli, C.; López-Huertas, M. Interdisciplinary Knowledge Organization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hjørland, B.G.C. Knowledge Organization (KO). Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization. Available online: https://www.isko.org/cyclo/knowledge_organization (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Rozo-Higuera, C. Topic Tendencies in Global Studies: Beyond the Boundaries of Regions and Disciplines in 30 Years of Publication Using Bibliometrics. New Glob. Stud. 2024. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Solla Price, D.J. Littel Science, Big Science; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. The Matthew Effect in Science. Science 1968, 159, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, B. On the Extensions of Concepts and the Growth of Knowledge. Sociol. Rev. 1982, 30, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchart, A. Statistical Bibliography or Bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, E. Citation Measures Used as an Objective Estimate of Creativity. Curr. Contents 1970, 1, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, C.; Larivière, V. Measuring Research: What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Borner, K.; Chen, C.; Boyack, K.W. Visualizing Knowledge Domains. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 179–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. Scientography: Mapping the Tracks of Science. Curr. Contents Soc. Behav. Sci. 1994, 5, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Knowledge Domain Visualization. In Information Visualization Beyond the Horizon; Springer: London, UK, 2006; pp. 143–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bawden, D.; Robinson, L. Introduction to Information Science; Facet Publising: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hjørland, B.; Hartel, J. Afterword: Ontological, Epistemological and Sociological Dimensions of Domains. Knowl. Organ. 2003, 30, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiraglia, R.P. Universes, Dimensions, Domains, Intensions and Extensions: Knowledge Organization for the 21st Century. In Categories, Contexts and Relations in Knowledge Organisation; Neelameghan, A., Raghavan, K.S., Eds.; Ergon Verlag: Wurzburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, E. Is Citation Analysis a Legitimate Evaluation Tool? Scientometrics 1979, 1, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H.G. Cited Documents as Concept Symbols. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1978, 8, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; McCain, K.W. Visualizing a Discipline: An Author Co-Citation Analysis of Information Science, 1972–1995. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 327–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Quesada, B.; de Moya-Anegón, F. Visualizing the Structure of Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Small, H. Co-citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Co-Citation Context Analysis and the Structure of Paradigms. J. Doc. 1980, 36, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees-Potter, L.K. Dynamic Thesaural Systems: A Bibliometric Study of Terminological and Conceptual Change in Sociology and Economics with Application to the Design of Dynamic. Inf. Process. Manag. 1989, 25, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, H.; Pedersen, J.O. A Cooccurrence-Based Thesaurus and Two Applications to Information Retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 1997, 33, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.W.; Borland, P. A Bibliometric-Based Semi-Automatic Approach to Identification of Candidate Thesaurus Terms: Parsing and Filtering of Noun Phrases from Citation Contexts. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Crestani, F., Ruthven, I., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2005; Volume 3507, pp. 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyack, K.W. Thesaurus-Based Methods for Mapping Contents of Publication Sets. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markscheffel, B. An Ontology Based Visualization Approach for the Joined Interpretation of Bibliometrics and Webometrics Data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management of Emergent Digital EcoSystems, MEDES’11, Luxembourg, 28–31 October 2013; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, C.; Robinson, L. Ontological Realism and Classification: Structures and Concepts in the Gene Ontology. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureev, V.N.; Mazov, N.A. Assessment of the Relevance of Journals in Research Libraries Using Bibliometrics (a Review). Sci. Tech. Inf. Process. 2015, 42, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastva, J.; Shank, J.; Gutzman, K.E.; Kaul, M.; Kubilius, R.K. Capturing and Analyzing Publication, Citation, and Usage Data for Contextual Collection Development. Ser. Libr. 2018, 74, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, G. Taking a Quantitative Approach to Collection Assessment: An Introduction to Bibliometrics in Practice. In Assessment as Information Practice; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Studies Consortium. About Us. Available online: https://globalstudiesconsortium.org/about/ (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Anheier, H.K.; Juergensmeyer, M.; Faessel, V. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Global Studies; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Juergensmeyer, M. Global Studies. In Encyclopedia of Global Studies; Anheier, H.K., Juergensmeyer, M., Eds.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 4, pp. 728–737. [Google Scholar]

- Middell, M. A New Discipline in the Making? In The Many Facets of Global Studies; Loeke, K., Middell, M., Eds.; Leipziger Universitätsverlag: Leipzig, Germany, 2019; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, W. Reconfiguring Area Studies for the Global Age. In Social Theory and Regional Studies in the Global Age; Arjomand, S.A., Ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 145–178. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, J. Introduction to Global Studies; Palgrave: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.B. What Is Global Studies? In The Oxford Handbook of Global Studies; Juergensmeyer, M., Faessel, V., Steger, M.B., Sassen, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov, A.N.; Mazour, I.I. Global Studies. In Global Studies Encyclopedic Dictionary; Chumakov, A.N., Mazour, I.I., Gay, W.C., Eds.; Rodopi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 223–225. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization Society of Knowledge (ISKO). The León Manifesto. Available online: http://www.iskoi.org/ilc/leon.php (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- López-Huertas, M.J. Gestión Del Conocimiento Multidimensional En Los Sistemas de Organización Del Conocimiento. In Actas del VIII Congreso ISKO-España; Bravo, B.R., Díez, M.L.A., Eds.; Universidad de León: León, Spain, 2007; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, S.R. Philosophy of Library Classification; Ejnar Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, H.E. The Organization of Knowledge and the Systems of Science; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, H.E. The Organization of Knowledge in Libraries; H.W. Wilson Company: New York, NY, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, H.A. The Power to Name; Springer: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.J. Historical Studies in Documentation a Short Biography of Henry Evelyn Bliss (1870–1955). J. Doc. 1976, 32, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoli, C. Integrative Levels Classification (ILC). Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization; Hjørland, B., Gnoli, C., Eds.; International Society for Knowledge Organization (ISKO): Toronto, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov, A.N.; Mazour, I.I.; Gay, W.C. Global Studies Encyclopedic Dictionary; Rodopi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iriye, A.; Saunier, P.Y. (Eds.) The Palgrave Dictionary of Transnational History; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garshol, L.M. Metadata? Thesauri? Taxonomies? Topic Maps! Making Sense of It All. J. Inf. Sci. 2004, 30, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostak, R. Integrating the Human Sciences: Enhancing Progress and Coherence Across the Social Sciences and Humanities; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tannuri Oliveira, E.F.; Cabrini Grácio, M.C. Studies of Author Cocitation Analysis: A Bibliometric Approach for Domain Analysis. IRIS-Rev. Informação Memória Tecnol. 2013, 2, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.N.; Li, D.D.; Robinson, N.; Liu, J. ping. Practical Guidance on Bibliometric Analysis and Mapping Knowledge Domains Methodology—A Summary. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 56, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, M. Knowledge Input for the Domain of Information Science. Aslib. Proc. 2013, 65, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, G.; Wang, C. Visual Topical Analysis of Library and Information Science. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 1753–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjurström, P.; Hammarfelt, B. On the Use of Bibliometrics for Domain Analysis: A Study of the Academic Field of Political Science in Europe; Uppsala Universitet: Uppsala, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Wenping, Y.; Cao, Z.; Dong, B.; Peng, X.; Jiang, N. Exploring the Domain of Emotional Intelligence in Organizations: Bibliometrics, Content Analyses, Framework Development, and Research Agenda. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 810507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kath, E.; Lee, J.C.H.; Warren, A. The Digital Global Condition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Author(s) | Title | Year | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM1 | Campbell, P.J., MacKinnon, A., and Stevens, C.R. | An introduction of Global Studies. | 2011 | Wiley-Blackwell |

| TM2 | O’Byrne, D.J. and Hensby, A. | Theorizing Global Studies. | 2011 | Palgrave Macmillan |

| TM3 | M. Juergensmeyer (Ed.) | Thinking Globally: A Global Studies Reader. | 2013 | University of California Press. |

| TS4 | Grinin, L.; Ilyin, I.; Hewrrmann, P.; and Korotayev, A. | Globalistics and Globalization Studies: Global Transformations and Global Future | Eds. 2012–2017 | Uchitel |

| TM5 | Smallman, S. and Brown, K. | Introduction to international and Global Studies. | 2015 | University of North Carolina Press |

| TM6 | Stoddart, E. and Collins, J. | Social and Cultural Foundations in Global Studies | 2016 | Routledge |

| TM7 | Steger, M.B. and Wahlrab, A. | What is Global Studies? Theory and practice. | 2017 | Routledge, Taylor, and Francis Group |

| TM8 | Darian-Smith, E. and McCarty, P.C. | The global turn: theories, research designs, and methods for Global Studies | 2017 | University of California |

| TM9 | McCormick, J. | Introduction to Global Studies. | 2018 | Palgrave |

| TM10 | Juergensmeyer, M.; Sassen, S.; Steger, M. B., and Faessel, V. (Eds.) | Oxford Handbook of Global Studies | 2019 | Oxford University Press |

| TM11 | Loecke, K. and Middell, M. (Eds.) | The many facets of Global Studies: Perspectives from the Erasmus Mundus Global Studies Programme | 2019 | Leipziger Universitätsverlag |

| TM12 | Cai, T. and Liu, Z. | Global Studies: Volume 1: Globalization and Globality | 2020 | Routledge |

| TM13 | Hamed Hosseini S.A., Goodman, J., Motta, S.C. and Gills, B. | The Routledge handbook of transformative global studies | 2021 | Routledge, Taylor, and Francis Group |

| Code | Author | Title | Year | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS1 | Anheier, H. K., Juergensmeyer, M., and Faessel, V. (Eds.). | The Encyclopedia of Global Studies [43] | 2012 | Sage |

| RS2 | Chumakov, A. N., Mazour, I. I., and Gay, W. C. (Eds.) | The Global Studies Encyclopedic Dictionary (2014) [56] | 2014 | Rodopi |

| RS3 | A. Iriye and P. Y. Saunier (Eds.) | Palgrave Dictionary of Transnational History (2009) [57] | 2009 | Palgrave Macmillan |

| Category | Sub-Category | Entry Term |

|---|---|---|

| History, Culture, and Society | Assets (non-tangible) and issues | Pacifism |

| Responsibility, Global | ||

| Hunger | ||

| Ethnic Cleansing | ||

| Gender Oppression | ||

| Theories, Views, and Ideas | Anthropocentrism | |

| Globalization, Social effects | ||

| Alarmism | ||

| Alienation | ||

| Consolation | ||

| Processes, States, and Periods | Civil disobedience | |

| Colonialism | ||

| Development, Social | ||

| Globalization, Historical stages of | ||

| Risk and Postmodern Society | ||

| Economy and Trade | Theories, Views, and Ideas | Economic Security |

| Capitalism | ||

| Ecometry | ||

| Economic Security | ||

| Economy, World | ||

| Processes, States, and Periods | Debt crisis | |

| Perestroika | ||

| Mergers and acquisitions | ||

| Capital, Transnational | ||

| Capital Punishment | ||

| Channels, Instruments, and Assets (Tangible) | Golden Billion | |

| Green Taxes | ||

| Composite Development Indices | ||

| Global Order and Politics | Theories, Views, and Ideas | Bipolar World |

| Center and Periphery | ||

| Political Culture | ||

| Modernity, Global Changes of | ||

| Globalization, limits of | ||

| Processes, States, and Periods | Japanese Post-War | |

| Migration | ||

| Mondialization | ||

| Age of Great Unity | ||

| Globalization | ||

| Actors (Active) | Al Qaeda | |

| Third World | ||

| States, Institutions, and Groups (9) | International Organizations | |

| European Union | ||

| NATO Response Force |

| Co-Occurred Terms (General) | Co-Occurred Terms (Countries/Geographies, Spaces) |

|---|---|

| Migration → identity Migration → ethnicity Migration → labor Global governance → organized civil society Global governance → policy formulation Economy → environment Economy → innovation Sustainable development → economic growth Global health → mortality Society → History Globalization → civil society Regional integration | United States → immigration Europe → immigrant population European Union → policy China → Chinese foreign policy Global production networks → China Global cities → inequality Eastern Europe → enlargement Responsibility → Lybia Global warming → Asia Pacific Power → China |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rozo-Higuera, C. A Mixed-Method Approach for Domain Analysis in Interdisciplinary Fields Using Bibliometrics: The Case of Global Studies. Information 2025, 16, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040304

Rozo-Higuera C. A Mixed-Method Approach for Domain Analysis in Interdisciplinary Fields Using Bibliometrics: The Case of Global Studies. Information. 2025; 16(4):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040304

Chicago/Turabian StyleRozo-Higuera, Carolina. 2025. "A Mixed-Method Approach for Domain Analysis in Interdisciplinary Fields Using Bibliometrics: The Case of Global Studies" Information 16, no. 4: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040304

APA StyleRozo-Higuera, C. (2025). A Mixed-Method Approach for Domain Analysis in Interdisciplinary Fields Using Bibliometrics: The Case of Global Studies. Information, 16(4), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040304