Exploiting Laser-Ablation ICP-MS for the Characterization of Salt-Derived Bismuth Films on Screen-Printed Electrodes: A Preliminary Investigation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Apparatus and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Bismuth Films Screen-Printed Electrodes from Insoluble Bismuth Phosphate

2.3. Measurement Procedures

2.4. LA-ICP-MS Analysis

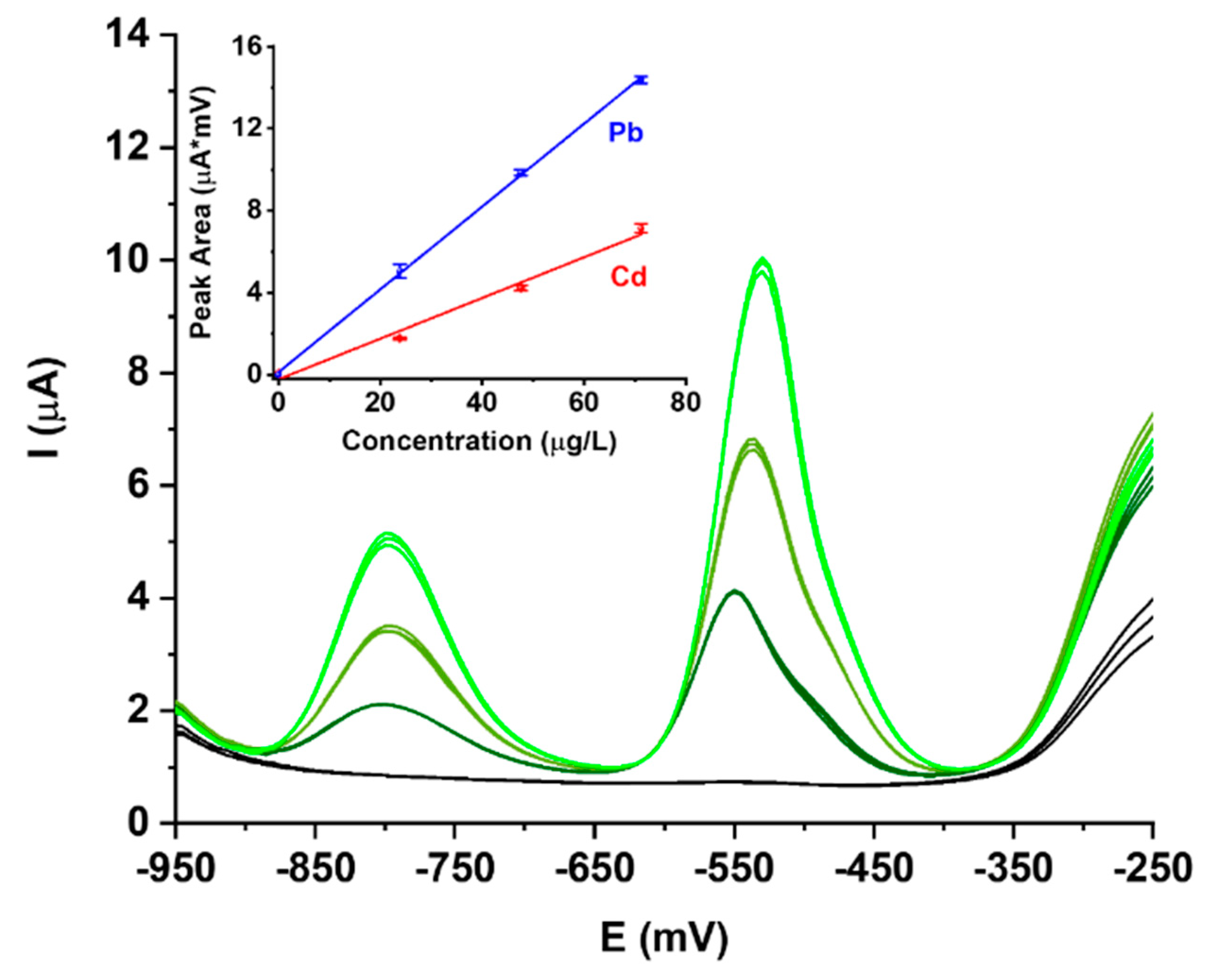

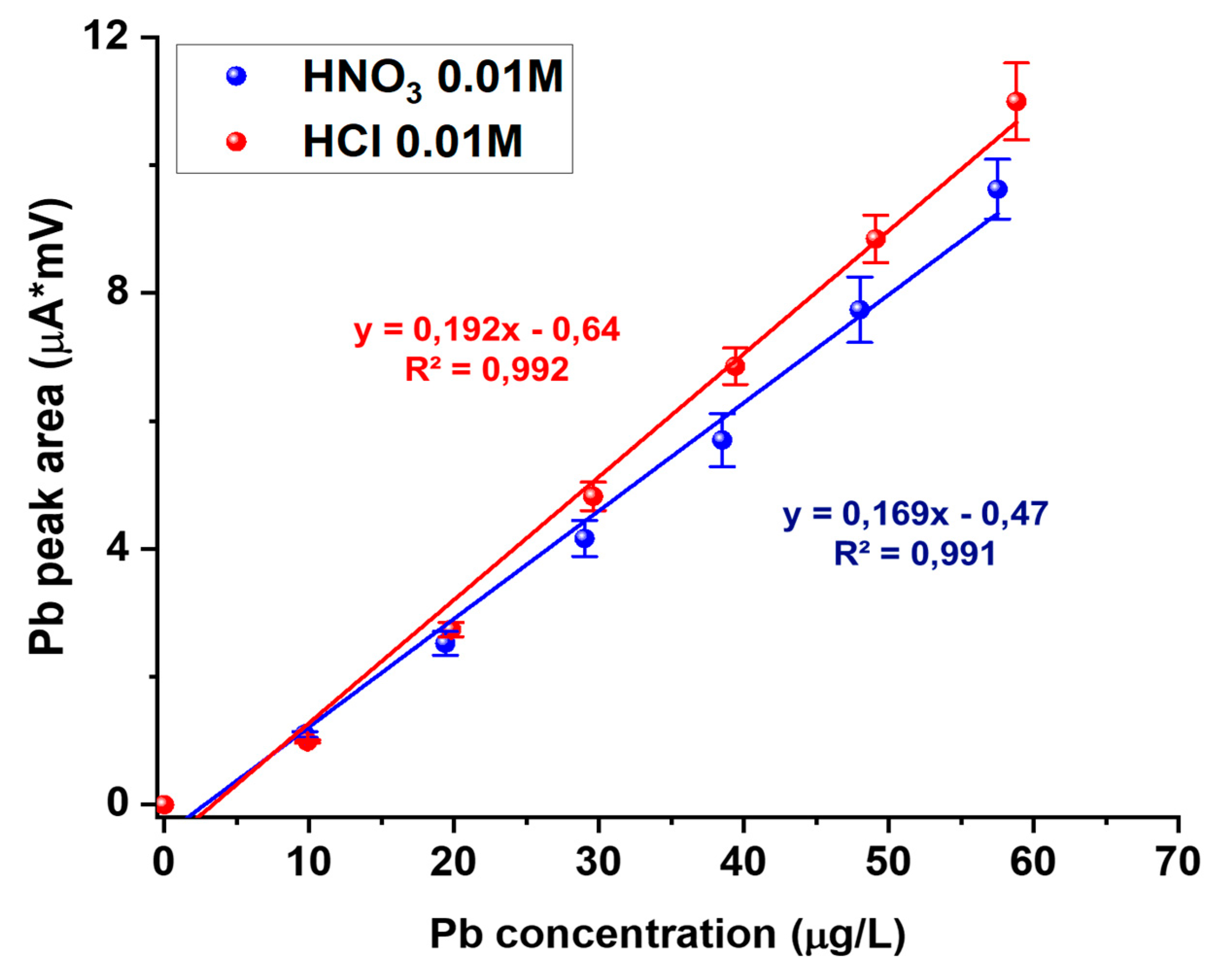

3. Results

3.1. Electrode Preparation

3.2. Laser Ablation-ICP-MS Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Hocevar, S.B.; Farias, P.A.; Ogorevc, B. Bismuth-Coated Carbon Electrodes for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 3218–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoĉevar, S.B.; Ogorevc, B.; Wang, J.; Pihlar, B. A Study on Operational Parameters for Advanced Use of Bismuth Film Electrode in Anodic Stripping Voltammetry. Electroanalysis 2002, 14, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarczyk, M.; Adamczyk, M. Bismuth film electrode and chloranilic acid as a new alternative for simple, fast and sensitive Ge(IV) quantification by adsorptive stripping voltammetry. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 15215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Y.; Liang, X.; Niyungeko, C.; Zhou, J.; Xu, J.; Tian, G. A review of the identification and detection of heavy metal ions in the environment by voltammetry. Talanta 2018, 178, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wu, H.; Ping, J. Simultaneous determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II) ions in honey and milk samples using a single-wallet carbon nanohorns modified screen-printed electrochemical sensor. Food Chem. 2019, 274, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, Y.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. Recent advances in nanomaterial- enabled screen-printed electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection. TrAC 2019, 115, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, A. Screen-printed electrodes modified with “Green” metals for electrochemical stripping analysis of Toxic Elements. Sensors 2018, 18, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lezi, N.; Vyskočil, V.; Economou, A.; Barek, J. Electroanalysis of Organic Compounds at Bismuth Electrodes: A Short Review. In Sensing in Electroanalysis; Kalcher, K., Metelka, R., Svancara, I., Vytras, K., Eds.; University Press Centre: Pardubice, Czech Republic, 2012; Volume 7, pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tyszczuk-Rotko, K.; Surowiec, K.; Szwagierek, A. Application of Eco-friendly Bismuth Film Electrode for the sensitive determination of Rutin. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2018, 14, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladislavic, N.; Buzuk, M.; Brinic, S.; Byljac, M.; Bralic, M. Morphological characterization of ex-situ prepared bismuth film electrodes and their application in the electroanalytical determination of the biomolecules. J. Sol. State Electr. 2016, 20, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandil, A.; Amine, A. Screen-Printed Electrodes Modified by Bismuth Film for the Determination of Released Lead in Moroccan Ceramics. Anal. Lett. 2009, 42, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo Quintana, J.; Arduini, F.; Amine, A.; Van Velzen, K.; Palleschi, G.; Moscone, D. Part two: Analytical optimisation of a procedure for lead detection in milk by means of bismuth-modified screen-printed electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 736, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dossi, C.; Monticelli, D.; Pozzi, A.; Recchia, S. Exploiting chemistry to improve performance of screen-printed, bismuth film electrodes (SP-BiFE). Biosensors 2016, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bedin, K.C.; Mitsuyasu, E.Y.; Ronix, A.; Cazetta, A.L.; Pezoti, O.; Almeida, V.C. Inexpensive bismuth-film electrode supported on pencil-lead graphite for determination of Pb(II) and Cd(II) ions by anodic stripping voltammetry. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2018, 1473706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kefala, A.; Economou, A.; Voulgaropoulos, A. A study of Nafion-coated bismuth-film electrodes for the determination of trace metals by anodic stripping voltammetry. Analyst 2004, 129, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, J.; Luo, X.; Wang, F.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Liu, D.; Chen, D.; Wei, J.; Liu, Y. Synergetic sensing effect of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose and bismuth on cadmium detection by differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry. Sensors 2019, 19, 5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malakhova, N.A.; Stojko, N.Y.; Brainina, K.Z. Novel approach to bismuth modifying procedure for voltammetric thick film carbon containing electrodes. Electrochem. Comm. 2007, 9, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladislavic, N.; Buzuk, M.; Buljac, M.; Kozuk, S.; Bralic, M.; Brinic, S. Sensitive electrochemical determination of folic acid using ex-situ prepared bismuth film electrodes. Croat. Chem. Acta 2017, 90, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardelly, J.K.B.; Lapolli, F.R.; Gomes da Silva Cruz, C.M.; Floriano, J.B. Determination of zinc and cadmium with characterized electrodes of carbon and polyurethane modified by a bismuth film. Mat. Res. 2011, 14, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Kolosov, V.; Yushkov, A.A.; Veretennikov, L.M. Recrystallization and investigation of bismuth thin film IOP by means of electron beams in transmission electron microscopy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1115, 032087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyszczuk-Rotko, K.; Metelka, R.; Vytřas, K.; Barczak, M.; Sadok, I.; Mirosław, B. A simple and easy way to enhance sensitivity of Sn(IV) on bismuth film electrodes with the use of a mediator. Mon. Chem. Chem. Mon. 2016, 147, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Zhou, L.; Lan, C.; Fan, F.; Xie, R.; Tan, H.; Xie, T.; Zhao, L. Nanostructured carbon black for simultaneous electrochemical determination of trace lead and cadmium by differential pulse stripping voltammetry. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mazzaracchio, V.; Tomei, M.R.; Cacciotti, I.; Chiodoni, A.; Novara, C.; Castellino, M.; Scordo, G.; Amine, A.; Moscone, D.; Arduini, F. Inside the different types of carbon black as nanomodifiers for screen-printed electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 317, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, F.; Giotta, L.; Chirizzi, D.; Papazoglou, S.; Kryou, C.; De Bartolomeo, A.; De Leo, V.; Guascito, M.R.; Zergioti, I. Phosphate Modified Screen Printed Electrodes by LIFT Treatment for Glucose Detection. Biosensors 2018, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monticelli, D.; Di Iorio, A.; Ciceri, E.; Castelletti, A.; Dossi, C. Tree ring microanalysis by LA–ICP–MS for environmental monitoring: Validation or refutation? Two case histories. Microchim. Acta 2009, 164, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amman, A.A. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP MS): A versatile tool. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arduini, F.; Amine, A.; Moscone, D.; Ricci, F.; Palleschi, G. Fast, sensitive and cost-effective detection of nerve agents in the gas phase using a portable instrument and an electrochemical biosensor. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 388, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, F.; Cassisi, A.; Amine, A.; Ricci, F.; Moscone, D.; Palleschi, G. Electrocatalytic oxidation of thiocholine at chemically modified cobalt hexacyanoferrate screen-printed electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2009, 626, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palchetti, I.; Laschi, S.; Mascini, M. Miniaturised stripping-based carbon modified sensor for in field analysis of heavy metals. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 530, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, D.; Castelletti, A.; Civati, D.; Recchia, S.; Dossi, C. How to Efficiently Produce Ultrapure Acids. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, D.; Civati, D.; Giussani, B.; Dossi, C.; Spanu, D.; Recchia, S. A viscous film sample chamber for Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma—Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2018, 179, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Laser Ablation Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Scan Speed | 20 μm/s |

| % output | 20% |

| Step rate | 20 Hz |

| Laser spot size | 80 μm |

| Distance between each laser scan | 260 μm |

| Mass Spectrometer Parameters | |

| Dwell Time | 40 ms |

| PC Detector | 3300 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dossi, C.; Binda, G.; Monticelli, D.; Pozzi, A.; Recchia, S.; Spanu, D. Exploiting Laser-Ablation ICP-MS for the Characterization of Salt-Derived Bismuth Films on Screen-Printed Electrodes: A Preliminary Investigation. Biosensors 2020, 10, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10090119

Dossi C, Binda G, Monticelli D, Pozzi A, Recchia S, Spanu D. Exploiting Laser-Ablation ICP-MS for the Characterization of Salt-Derived Bismuth Films on Screen-Printed Electrodes: A Preliminary Investigation. Biosensors. 2020; 10(9):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10090119

Chicago/Turabian StyleDossi, Carlo, Gilberto Binda, Damiano Monticelli, Andrea Pozzi, Sandro Recchia, and Davide Spanu. 2020. "Exploiting Laser-Ablation ICP-MS for the Characterization of Salt-Derived Bismuth Films on Screen-Printed Electrodes: A Preliminary Investigation" Biosensors 10, no. 9: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10090119

APA StyleDossi, C., Binda, G., Monticelli, D., Pozzi, A., Recchia, S., & Spanu, D. (2020). Exploiting Laser-Ablation ICP-MS for the Characterization of Salt-Derived Bismuth Films on Screen-Printed Electrodes: A Preliminary Investigation. Biosensors, 10(9), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios10090119