Asynchronous Magnetic Bead Rotation (AMBR) Microviscometer for Label-Free DNA Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Reagents

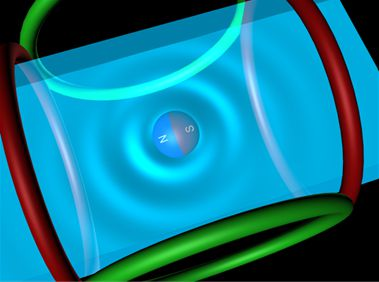

2.2. Viscosity Measurement

2.3. Preparation of Digestion Reaction Samples

2.4. Preparation of PCR Samples

2.5. Gel Electrophoresis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Calibration of AMBR Viscometer

3.2. Viscosity Measurement of DNA Aqueous Solutions

| Experimental Results | Expected Range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Conc. (g/L) | Rotation Period (s) | Viscosity (cP) | Min Viscosity (cP) | Max Viscosity (cP) |

| 0.00 | 2.40 ± 0.24 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| 0.02 | 2.70 ± 0.64 | 0.96 ± 0.14 | 0.94 | 1.07 |

| 0.05 | 3.12 ± 0.62 | 1.06 ± 0.14 | 1.02 | 1.34 |

| 0.09 | 3.87 ± 0.21 | 1.22 ± 0.05 | 1.15 | 1.78 |

| 0.19 | 5.86 ± 0.49 | 1.67 ± 0.11 | 1.41 | 2.67 |

| 0.35 | 9.52 ± 1.53 | 2.48 ± 0.34 | 1.85 | 4.18 |

3.3. Measurement of DNA Reaction Progression

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Y.-W.; Procop, G.W.; Persing, D.H. Molecular diagnostics of infectious diseases. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 2021–2038. [Google Scholar]

- Valasek, M.A.; Repa, J.J. The power of real-time PCR. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2005, 29, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Biswas, A.; Choi, K.; Pal, U. Methods for rapid detection of foodborne pathogens: An overview. Am. J. Food Technol. 2011, 6, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oorschot, R.; Ballantyne, K.N.; Mitchell, R.J. Forensic trace DNA: A review. Investig. Genet. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landegren, U.; Kaiser, R.; Caskey, C.T.; Hood, L. DNA diagnostics—Molecular techniques and automation. Science 1988, 242, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kubista, M.; Andrade, J.M.; Bengtsson, M.; Forootan, A.; Jonak, J.; Lind, K.; Sindelka, R.; Sjoback, R.; Sjogreen, B.; Strombom, L.; Stahlberg, A.; Zoric, N. The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006, 27, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handal, M.I.; Ugaz, V.M. DNA mutation detection and analysis using miniaturized microfluidic systems. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2006, 6, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Mahon, A.R.; Barnes, M.A.; Feder, J.; Lodge, D.M.; Hwang, C.-T.; Schafer, R.; Ruggiero, S.T.; Tanner, C.E. Quantitative and rapid DNA detection by laser transmission spectroscopy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakite, M.L.; Champ, J.; Descroix, S.; Malaquin, L.; Amblard, F.; Viovy, J.L. A low-cost, label-free DNA detection method in lab-on-chip format based on electrohydrodynamic instabilities, with application to long-range PCR. Lab Chip 2012, 12, 4738–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D.C.; Li, J.; Strachan, B.C.; Begley, M.R.; Finkler, D.; Bazydlo, L.A.; Barker, N.S.; Haverstick, D.M.; Utz, M.; Landers, J.P. New detection modality for label-free quantification of DNA in biological samples via superparamagnetic bead aggregation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5689–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak-Dahl, E.; Lee, J.; Burns, M.A. Nanoliter droplet viscometer with additive-free operation. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Davenport, R.D.; Burns, M.A. Nanoliter viscometer for analyzing blood plasma and other liquid samples. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, M.L. The viscosity of dilute solutions of long-chain molecules. IV. Dependence on concentration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1942, 64, 2716–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.D.; Scruggs, R.L. Viscosity study of DNA. II. The effect of simple salt concentration on the viscosity of high molecular weight DNA and application of viscometry to the study of DNA isolated from T4 and T5 bacteriophage mutants. Biopolymers 1968, 6, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsortos, A.; Papadakis, G.; Gizeli, E. The intrinsic viscosity of linear DNA. Biopolymers 2011, 95, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, L.H.; Oene, H.V. Shear dependence in the viscometry of high polymer solutions: A new variable-shear capillary viscometer. Can. J. Chem. 1961, 39, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheely, M.L. Glycerol viscosity tables. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1932, 24, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, P.; Sinn, I.; McNaughton, B.H.; Newton, D.W.; Burns, M.A.; Kopelman, R. Monitoring the growth and drug susceptibility of individual bacteria using asynchronous magnetic bead rotation sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2751–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, B.; Agayan, R.; Wang, J.; Kopelman, R. Physiochemical microparticle sensors based on nonlinear magnetic oscillations. Sens. Actuator B Chem. 2007, 121, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, I.; Kinnunen, P.; Albertson, T.; McNaughton, B.H.; Newton, D.W.; Burns, M.A.; Kopelman, R. Asynchronous magnetic bead rotation (AMBR) biosensor in microfluidic droplets for rapid bacterial growth and susceptibility measurements. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 2604–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, G.; Pieranski, P.; Skjeltorp, A. Dynamic behavior of simple magnetic hole systems. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 42, 7271–7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, G.; Pieranski, P.; Skjeltorp, A. Nonlinear phenomena in systems of magnetic holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevry, L.; Sampathkumar, N.; Cebers, A.; Berret, J.F. Magnetic wire-based sensors for the microrheology of complex fluids. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frka-Petesic, B.; Erglis, K.; Berret, J.F.; Cebers, A.; Dupuis, V.; Fresnais, J.; Sandre, O.; Perzynski, R. Dynamics of paramagnetic nanostructured rods under rotating field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2011, 323, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, A.; Luzinov, I.; Owens, J.R.; Kornev, K.G. Magnetic rotational spectroscopy with nanorods to probe time-dependent rheology of microdroplets. Langmuir 2012, 28, 10064–10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Pierre, T.G.S.; Dobson, J. Experimental evaluation of the magnetic properties of commercially available magnetic microspheres. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2005, 15, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Sinn, I.; Kinnunen, P.; Pei, S.N.; Clarke, R.; McNaughton, B.H.; Kopelman, R. Magnetically uniform and tunable Janus particles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Larson, R.G. The scaling of zero-shear viscosities of semidilute polymer solutions with concentration. J. Rheol. 2005, 49, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, A.; Commiskey, P.; Shah, N.; Kopelman, R. Bead assembly magnetorotation as a signal transduction method for protein detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 48, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Appendix

Analysis of Figure A3

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Burke, D.T.; Kopelman, R.; Burns, M.A. Asynchronous Magnetic Bead Rotation (AMBR) Microviscometer for Label-Free DNA Analysis. Biosensors 2014, 4, 76-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios4010076

Li Y, Burke DT, Kopelman R, Burns MA. Asynchronous Magnetic Bead Rotation (AMBR) Microviscometer for Label-Free DNA Analysis. Biosensors. 2014; 4(1):76-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios4010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yunzi, David T. Burke, Raoul Kopelman, and Mark A. Burns. 2014. "Asynchronous Magnetic Bead Rotation (AMBR) Microviscometer for Label-Free DNA Analysis" Biosensors 4, no. 1: 76-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios4010076

APA StyleLi, Y., Burke, D. T., Kopelman, R., & Burns, M. A. (2014). Asynchronous Magnetic Bead Rotation (AMBR) Microviscometer for Label-Free DNA Analysis. Biosensors, 4(1), 76-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios4010076