Cannabinoids in Periodontology: Where Are We Now?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Cannabinoids Definitions

3. Cannabinoid Receptors

4. Cannabinoid Effects on the Immune System

5. Cannabinoid Antimicrobial Properties

6. Cannabinoid Potential in the Treatment of Periodontitis

6.1. Effects of Cannabinoids on the Oral Microbiota

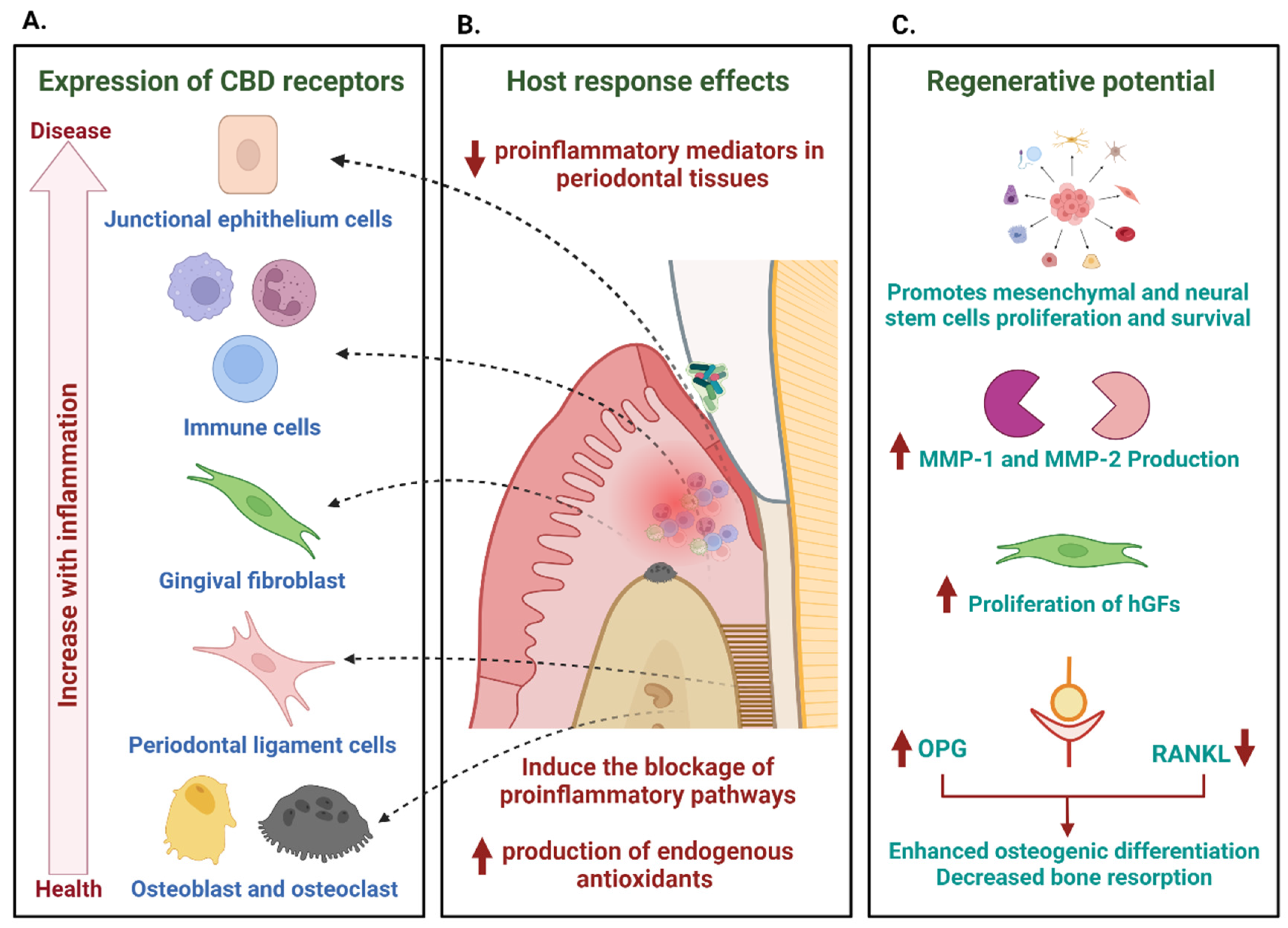

6.2. Expression of Cannabinoid Receptors in the Periodontium

6.3. Effects of Cannabinoids on Periodontal Inflammation Modulation

6.4. Regenerative Potential of Cannabinoids at the Periodontium

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cho, C.; Hirsch, R.; Johnstone, S. General and oral health implications of cannabis use. Aust. Dent. J. 2005, 50, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, J.; Rojas, M.; Espinoza, C. Clinical Use of Marijuana: The Thin Line Between Good and Evil? Arch. Med. Res. 2018, 49, 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleider, L.B.; Abuhasira, R.; Novack, V. Medical cannabis: Aligning use to evidence-based medicine approach. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2458–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, T.P.; Hindocha, C.; Green, S.F.; Bloomfield, M.A.P. Medicinal use of cannabis based products and cannabinoids. BMJ 2019, 365, l1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennici, A.; Mannucci, C.; Calapai, F.; Cardia, L.; Ammendolia, I.; Gangemi, S.; Calapai, G.; Soler, D.G. Safety of Medical Cannabis in Neuropathic Chronic Pain Management. Molecules 2021, 26, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdman, R.; Vigil, D.; Robinson, K.; Shah, P.; Contreras, A.E. Safety and Efficacy of Medical Cannabis in Autism Spectrum Disorder Compared with Commonly Used Medications. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022, 7, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylla, D.M.; Eklund, J.; Gilmore, G.; Gavenda, A.; Guggisberg, J.; VazquezBenitez, G.; Pawloski, P.A.; Arneson, T.; Richter, S.; Birnbaum, A.K.; et al. A randomized trial of medical cannabis in patients with stage IV cancers to assess feasibility, dose requirements, impact on pain and opioid use, safety, and overall patient satisfaction. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7471–7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, D.; Shapira, L. An update on the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, D.; Sanui, T.; Nishimura, F.; Shapira, L. Diabetes as a risk factor for periodontal disease—Plausible mechanisms. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Del Castillo, A.M.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis and Cardiovascular Diseases. Consensus Report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; Konradi, A.; Nguyen, M.; Haditsch, U.; Raha, D.; Griffin, C.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 23, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyke, T.E.; Bartold, P.M.; Reynolds, E.C. The Nexus Between Periodontal Inflammation and Dysbiosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.C. Cannabinoids for the treatment of inflammation. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2007, 8, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Junior, N.C.F.; dos-Santos-Pereira, M.; Guimarães, F.S.; Del Bel, E. Cannabidiol and Cannabinoid Compounds as Potential Strategies for Treating Parkinson’s Disease and l-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 37, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Junior, N.C.; Campos, A.C.; Guimarães, F.S.; Del-Bel, E.; Zimmermann, P.M.d.R.; Junior, L.B.; Hallak, J.E.; Crippa, J.A.; Zuardi, A.W. Biological bases for a possible effect of cannabidiol in Parkinson’s disease. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, R.; Gupta, V.; Suphioglu, C. Current Aspects of the Endocannabinoid System and Targeted THC and CBD Phytocannabinoids as Potential Therapeutics for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases: A Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 4878–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, T.E.; Szaflarski, J.P. Cannabis for the Treatment of Epilepsy: An Update. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 18, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienzl, M.; Storr, M.; Schicho, R. Cannabinoids and Opioids in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milando, R.; Friedman, A. Cannabinoids: Potential Role in Inflammatory and Neoplastic Skin Diseases. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunda, F.; Arowolo, A. A molecular basis for the anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrosis properties of cannabidiol. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 14083–14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryimak, N.; Zaiachuk, M.; Kovalchuk, O.; Kovalchuk, I. The Potential Use of Cannabis in Tissue Fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Sloan, L.; Saxena, D.; Scott, D.A. The Antimicrobial Properties of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Compounds and Relevance to CB2-Targeted Neurodegenerative Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Elliott, A.G.; Zhang, B.; Ramu, S.; Amado, M.; Lowe, G.J.; Hinton, A.O.; Pham, D.M.T.; Zuegg, J.; et al. The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, V.L.; Gonçalves, J.L.; Aguiar, J.; Teixeira, H.M.; Câmara, J.S. The synthetic cannabinoids phenomenon: From structure to toxicological properties. A review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2020, 50, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, G.; Sakr, B.; Rizack, T. Medical Marijuana Use in Oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellati, F.; Borgonetti, V.; Brighenti, V.; Biagi, M.; Benvenuti, S.; Corsi, L. Cannabis sativa L. and Nonpsychoactive Cannabinoids: Their Chemistry and Role against Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Hausman, J.-F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis sativa: The Plant of the Thousand and One Molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. Cannabinoid pharmacology: The first 66 years. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147 (Suppl. 1), S163–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C. The cannabinoid receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002, 68–69, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katchan, V.; David, P.; Shoenfeld, Y. Cannabinoids and autoimmune diseases: A systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharkey, K.A.; Wiley, J.W. The Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Brain–Gut Axis. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, M.A.; Wotjak, C.T. Role of the endocannabinoid system in regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Brain Res. 2008, 170, 397–432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Laurentiis, A.; Correa, F.; Solari, J.F. Endocannabinoid System in the Neuroendocrine Response to Lipopolysaccharide-induced Immune Challenge. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 6, bvac120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Y.; McKallip, R.J.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. Activation through Cannabinoid Receptors 1 and 2 on Dendritic Cells Triggers NF-κB-Dependent Apoptosis: Novel Role for Endogenous and Exogenous Cannabinoids in Immunoregulation. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greineisen, W.E.; Turner, H. Immunoactive effects of cannabinoids: Considerations for the therapeutic use of cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxford, J.L.; Yamamura, T. Cannabinoids and the immune system: Potential for the treatment of inflammatory diseases? J Neuroimmunol. 2005, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgelt, L.M.; Franson, K.L.; Nussbaum, A.M.; Wang, G.S. The Pharmacologic and Clinical Effects of Medical Cannabis. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2013, 33, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljaschewitsch, E.; Witting, A.; Mawrin, C.; Lee, T.; Schmidt, P.M.; Wolf, S.; Hoertnagl, H.; Raine, C.S.; Schneider-Stock, R.; Nitsch, R.; et al. The Endocannabinoid Anandamide Protects Neurons during CNS Inflammation by Induction of MKP-1 in Microglial Cells. Neuron 2006, 49, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, V.; De Petrocellis, L. Why do cannabinoid receptors have more than one endogenous ligand? Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2012, 367, 3216–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravian, N.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S.; Jimenez, J.J. Cannabidiol as a Novel Therapeutic for Immune Modulation. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2020, 9, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, C.; Millán, E.; García, V.; Appendino, G.; DeMesa, J.; Muñoz, E. The endocannabinoid system of the skin. A potential approach for the treatment of skin disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 157, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, M.; Egashira, N. New Perspectives in the Studies on Endocannabinoid and Cannabis: Abnormal Behaviors Associate With CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor and Development of Therapeutic Application. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004, 96, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, T.W. Cannabinoid-based drugs as anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.F.; Newton, C.; Widen, R.; Friedman, H.; Klein, T.W. Differential expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptor mRNA in mouse immune cell subpopulations and following B cell stimulation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 423, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipina, C.; Hundal, H.S. Modulation of cellular redox homeostasis by the endocannabinoid system. Open Biol. 2016, 6, 150276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, R.; Zuccaro, P.; Pichini, S.; Roset, P.N.; Poudevida, S.; Farré, M.; Segura, J.; de la Torre, R. Modulation of the Immune System in Cannabis Users. JAMA 2003, 289, 1929–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Scuderi, C.; Savani, C.; Steardo, L., Jr.; De Filippis, D.; Cottone, P.; Iuvone, T.; Cuomo, V.; Steardo, L. Cannabidiol in vivo blunts β-amyloid induced neuroinflammation by suppressing IL-1β and iNOS expression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Rajesh, M.; Patel, V.; Mukhopadhyay, B.; Gao, B.; Haskó, G.; Pacher, P. Cannabidiol attenuates cisplatin-Lnduced nephrotoxicity by decreasing oxidative/nitrosative stress, inflammation, and cell death. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 328, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Aviello, G.; Romano, B.; Orlando, P.; Capasso, R.; Maiello, F.; Guadagno, F.; Petrosino, S.; Capasso, F.; Di Marzo, V.; et al. Cannabidiol, a safe and non-psychotropic ingredient of the marijuana plant Cannabis sativa, is protective in a murine model of colitis. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 87, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Almeida, V.I.; Costola-de-Souza, C.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Pinheiro, M.L.; Vitoretti, L.B.; Gimenes-Junior, J.A.; Akamine, A.T.; Crippa, J.A.; Tavares-de-Lima, W.; et al. Cannabidiol improves lung function and inflammation in mice submitted to LPS-induced acute lung injury. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2015, 37, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuolo, F.; Petronilho, F.; Sonai, B.; Ritter, C.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.; Dal-Pizzol, F. Evaluation of Serum Cytokines Levels and the Role of Cannabidiol Treatment in Animal Model of Asthma. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 538670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juknat, A.; Pietr, M.; Kozela, E.; Rimmerman, N.; Levy, R.; Gao, F.; Coppola, G.; Geschwind, D.; Vogel, Z. Microarray and Pathway Analysis Reveal Distinct Mechanisms Underlying Cannabinoid-Mediated Modulation of LPS-Induced Activation of BV-2 Microglial Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demuth, D.G.; Molleman, A. Cannabinoid signalling. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, F.; Fasolino, I.; Romano, B.; Capasso, R.; Maiello, F.; Coppola, D.; Orlando, P.; Battista, G.; Pagano, E.; Di Marzo, V.; et al. Beneficial effect of the non-psychotropic plant cannabinoid cannabigerol on experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massa, F.; Marsicano, G.; Hermann, H.; Cannich, A.; Monory, K.; Cravatt, B.F.; Ferri, G.-L.; Sibaev, A.; Storr, M.; Lutz, B. The endogenous cannabinoid system protects against colonic inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.P.; Singh, N.P.; Singh, B.; Price, R.L.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.S. Cannabinoid receptor-2 (CB2) agonist ameliorates colitis in IL-10 -/- mice by attenuating the activation of T cells and promoting their apoptosis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 258, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naftali, T.; Schleider, L.B.-L.; Dotan, I.; Lansky, E.P.; Benjaminov, F.S.; Konikoff, F.M. Cannabis Induces a Clinical Response in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: A Prospective Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 1276–1280.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, M.; Nasser, M.W.; Ravi, J.; Wani, N.A.; Ahirwar, D.K.; Zhao, H.; Oghumu, S.; Satoskar, A.R.; Shilo, K.; Carson, W.E.; et al. Modulation of the tumor microenvironment and inhibition of EGF/EGFR pathway: Novel anti-tumor mechanisms of Cannabidiol in breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.P. Cannabinoids for Symptom Management and Cancer Therapy: The Evidence. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2016, 14, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.; Zeira, M.; Reich, S.; Har-Noy, M.; Mechoulam, R.; Slavin, S.; Gallily, R. Cannabidiol lowers incidence of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Autoimmunity 2006, 39, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfait, A.M.; Gallily, R.; Sumariwalla, P.F.; Malik, A.S.; Andreakos, E.; Mechoulam, R.; Feldmann, M. The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 9561–9566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvi, E.; Lorenzini, S.; Garcia-Gonzalez, E.; Maggio, R.; E Lazzerini, P.; Capecchi, P.L.; Balistreri, E.; Spreafico, A.; Niccolini, S.; Pompella, G.; et al. Inhibitory effect of synthetic cannabinoids on cytokine production in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2008, 26, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sumariwalla, P.F.; Gallily, R.; Tchilibon, S.; Fride, E.; Mechoulam, R.; Feldmann, M. A novel synthetic, nonpsychoactive cannabinoid acid (HU-320) with antiinflammatory properties in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Hankey, D.J.R.; Jackson, S.J.; Croxford, J.L.; Pocock, J.M.; Ledent, C.; Petzold, A.; Thompson, A.J.; Giovannoni, G.; et al. Cannabinoids inhibit neurodegeneration in models of multiple sclerosis. Brain 2003, 126, 2191–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozela, E.; Lev, N.; Kaushansky, N.; Eilam, R.; Rimmerman, N.; Levy, R.; Ben-Nun, A.; Juknat, A.; Vogel, Z. Cannabidiol inhibits pathogenic T cells, decreases spinal microglial activation and ameliorates multiple sclerosis-like disease in C57BL/6 mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klingeren, B.; ten Ham, M. Antibacterial activity of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1976, 42, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appendino, G.; Gibbons, S.; Giana, A.; Pagani, A.; Grassi, G.; Stavri, M.; Smith, E.; Rahman, M.M. Antibacterial Cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: A Structure−Activity Study. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, M.A.; El-Halfawy, O.M.; Gale, R.T.; MacNair, C.R.; Carfrae, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Jentsch, N.G.; Magolan, J.; Brown, E.D. Uncovering the Hidden Antibiotic Potential of Cannabis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Menghini, L.; Di Sotto, A.; Mancinelli, R.; Sisto, F.; Carradori, S.; Cesa, S.; Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; Angiolella, L.; et al. Chromatographic Analyses, In Vitro Biological Activities, and Cytotoxicity of Cannabis sativa L. Essential Oil: A Multidisciplinary Study. Molecules 2018, 23, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseppi, R.; Brighenti, V.; Licata, M.; Lambertini, A.; Sabia, C.; Messi, P.; Pellati, F.; Benvenuti, S. Chemical Characterization and Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils from Fibre-Type Cannabis sativa L. (Hemp). Molecules 2019, 24, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasim, K.; Haq, I.; Ashraf, M. Antimicrobial studies of the leaf of Cannabis sativa L. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 1995, 8, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nissen, L.; Zatta, A.; Stefanini, I.; Grandi, S.; Sgorbati, B.; Biavati, B.; Monti, A. Characterization and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of industrial hemp varieties (Cannabis sativa L.). Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardo, M.E.V.; Mendieta, J.R.; Villamonte, M.D.; Colman, S.L.; Nercessian, D. Antifungal and antibacterial activities of Cannabis sativa L. resins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 116839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, M.; Smoum, R.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Antimicrobial potential of endocannabinoid and endocannabinoid-like compounds against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Smoum, R.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Potential combinations of endocannabinoid/endocannabinoid-like compounds and antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Singh, S.; Niyogi, R.G.; Lamont, G.J.; Wang, H.; Lamont, R.J.; Scott, D.A. Marijuana-Derived Cannabinoids Trigger a CB2/PI3K Axis of Suppression of the Innate Response to Oral Pathogens. Front Immunol. 2019, 15, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Sionov, R.V.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Cannabidiol against Candida albicans. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionov, R.V.; Feldman, M.; Smoum, R.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Anandamide prevents the adhesion of filamentous Candida albicans to cervical epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, K.; Stahl, V. Cannabinoids infused mouthwash products are as effective as chlorhexidine on inhibition of total-culturable bacterial content in dental plaque samples. J. Cannabis Res. 2020, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozono, S.; Matsuyama, T.; Biwasa, K.K.; Kawahara, K.-I.; Nakajima, Y.; Yoshimoto, T.; Yonamine, Y.; Kadomatsu, H.; Tancharoen, S.; Hashiguchi, T.; et al. Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in periodontal healing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 394, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konermann, A.; Jäger, A.; Held, S.A.E.; Brossart, P.; Schmöle, A. In vivo and In vitro Identification of Endocannabinoid Signaling in Periodontal Tissues and Their Potential Role in Local Pathophysiology. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 37, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, Y.; Furuichi, Y.; Biswas, K.K.; Hashiguchi, T.; Kawahara, K.I.; Yamaji, K.; Uchimura, T.; Izumi, Y.; Maruyama, I. Endocannabinoid, anandamide in gingival tissue regulates the periodontal inflammation through NF-κB pathway inhibition. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäger, A.; Setiawan, M.; Beins, E.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.; Konermann, A. Analogous modulation of inflammatory responses by the endocannabinoid system in periodontal ligament cells and microglia. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, S.; Thomas, K.L.; Abu-Shaar, M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 1993, 365, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Qi, X.; Alhabeil, J.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Z. Activation of cannabinoid receptors promote periodontal cell adhesion and migration. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossola, C.A.; Surkin, P.N.; Mohn, C.E.; Elverdin, J.C.; Fernández-Solari, J. Anti-Inflammatory and Osteoprotective Effects of Cannabinoid-2 Receptor Agonist HU-308 in a Rat Model of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, G.; Carmagnola, D.; Toma, M.; Rasperini, G.; Orioli, M.; Dellavia, C. Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in current and recurrent periodontitis: A human study. J. Periodontal Res. 2023, 58, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettori, E.; De Laurentiis, A.; Zubilete, M.Z.; Rettori, V.; Elverdin, J.C. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of the Endocannabinoid Anandamide in Experimental Periodontitis and Stress in the Rat. Neuroimmunomodulation 2012, 19, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, A.H.; Presley, C.S.; Dabbous, M.; Tipton, D.A.; Mustafa, S.M.; Moore, B.M. Anti-inflammatory activity of cannabinoid receptor 2 ligands in primary hPDL fibroblasts. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 87, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskan, M.; Gevrek, F. PPAR-γ, RXR, VDR, and COX-2 Expressions in gingival tissue samples of healthy individuals, periodontitis and peri-implantitis patients. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, A.V.; Saigh, M.A.; McCulloch, C.A.; Glogauer, M. The Role of NrF2 in the Regulation of Periodontal Health and Disease. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDew-White, M.; Lee, E.; Alvarez, X.; Sestak, K.; Ling, B.J.; Byrareddy, S.N.; Okeoma, C.M.; Mohan, M. Cannabinoid control of gingival immune activation in chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques involves modulation of the indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-1 pathway and salivary microbiome. EBioMedicine 2021, 75, 103769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiricosta, L.; Silvestro, S.; Pizzicannella, J.; Diomede, F.; Bramanti, P.; Trubiani, O.; Mazzon, E. Transcriptomic Analysis of Stem Cells Treated with Moringin or Cannabidiol: Analogies and Differences in Inflammation Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, S.Y.; Dabbous, M.K.; Tipton, D.A. Effect of cannabidiol on human gingival fibroblast extracellular matrix metabolism: MMP production and activity, and production of fibronectin and transforming growth factor β. J. Periodontal Res. 2012, 47, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susin, C.; Wikesjö, U.M.E. Regenerative periodontal therapy: 30 years of lessons learned and unlearned. Periodontology 2000 2013, 62, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallat, A.; Lotersztajn, S. Endocannabinoids and Liver Disease. I. Endocannabinoids and their receptors in the liver. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007, 294, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ovejero, D.; Arevalo-Martin, A.; Petrosino, S.; Docagne, F.; Hagen, C.; Bisogno, T.; Watanabe, M.; Guaza, C.; Di Marzo, V.; Molina-Holgado, E. The endocannabinoid system is modulated in response to spinal cord injury in rats. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 33, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.A.; Camilleri, M. Cannabinoids in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 60, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Han, C.; Li, S.; Huo, N.; Ding, Y.; Duan, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sang, H. Activation of cannabinoid receptor CB2 regulates osteogenic and osteoclastogenic gene expression in human periodontal ligament cells. J. Periodontal Res. 2010, 45, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napimoga, M.H.; Benatti, B.B.; Lima, F.O.; Alves, P.M.; Campos, A.C.; Pena-Dos-Santos, D.R.; Severino, F.P.; Cunha, F.Q.; Guimarães, F.S. Cannabidiol decreases bone resorption by inhibiting RANK/RANKL expression and pro-inflammatory cytokines during experimental periodontitis in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofek, O.; Karsak, M.; Leclerc, N.; Fogel, M.; Frenkel, B.; Wright, K.; Tam, J.; Attar-Namdar, M.; Kram, V.; Shohami, E.; et al. Peripheral cannabinoid receptor, CB2, regulates bone mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossola, C.A.; Balcarcel, N.B.; Astrauskas, J.I.; Bozzini, C.; Elverdin, J.C.; Fernández-Solari, J. A new target to ameliorate the damage of periodontal disease: The role of transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 in contrast to that of specific cannabinoid receptors in rats. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Cao, Y.; Yang, H.; Han, N.; Zhu, X.; Fan, Z.; Du, J.; Zhang, F. CB1 enhanced the osteo/dentinogenic differentiation ability of periodontal ligament stem cells via p38 MAPK and JNK in an inflammatory environment. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Li, L.; Ge, L.; Zhang, F.; Fan, Z.; Hu, L. The cannabinoid receptor I (CB1) enhanced the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by rescue impaired mitochondrial metabolism function under inflammatory condition. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossola, C.; Rodas, J.; Balcarcel, N.; Astrauskas, J.; Elverdin, J.; Fernández-Solari, J. Signs of alveolar bone damage in early stages of periodontitis and its prevention by stimulation of cannabinoid receptor Model in rats. Acta Odontológica Latinoam 2020, 33, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, N.B.; Jurj, A.; Sorițău, O.; Lucaciu, O.P.; Dirzu, N.; Raduly, L.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Cenariu, M.; Boșca, B.A.; Campian, R.S.; et al. Cannabidiol and Vitamin D3 Impact on Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Medicina 2020, 56, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreekachon, P.; Chaichana, N.; Makeudom, A.; Kerdvongbundit, V.; Krisanaprakornkit, W.; Krisanaprakornkit, S. Proliferative effect of cannabidiol in human gingival fibroblasts via the mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) 1. J. Periodontal. Res. 2023, 58, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libro, R.; Scionti, D.; Diomede, F.; Marchisio, M.; Grassi, G.; Pollastro, F.; Piattelli, A.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E.; Trubiani, O. Cannabidiol Modulates the Immunophenotype and Inhibits the Activation of the Inflammasome in Human Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariccio, V.L.; Scionti, D.; Raffa, A.; Iori, R.; Pollastro, F.; Diomede, F.; Bramanti, P.; Trubiani, O.; Mazzon, E. Treatment of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells with MOR and CBD Promotes Cell Survival and Neuronal Differentiation via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carmona Rendón, Y.; Garzón, H.S.; Bueno-Silva, B.; Arce, R.M.; Suárez, L.J. Cannabinoids in Periodontology: Where Are We Now? Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121687

Carmona Rendón Y, Garzón HS, Bueno-Silva B, Arce RM, Suárez LJ. Cannabinoids in Periodontology: Where Are We Now? Antibiotics. 2023; 12(12):1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121687

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarmona Rendón, Yésica, Hernán Santiago Garzón, Bruno Bueno-Silva, Roger M. Arce, and Lina Janeth Suárez. 2023. "Cannabinoids in Periodontology: Where Are We Now?" Antibiotics 12, no. 12: 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121687