Ethnopharmacology, Antimicrobial Potency, and Phytochemistry of African Combretum and Pteleopsis Species (Combretaceae): A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Botany, Ethnopharmacology, and Importance in Herbal Markets of African Combretum and Pteleopsis Species

3.1. The Genus Combretum

3.1.1. Botany

3.1.2. Ethnopharmacology

| Species Name and Geographical Occurence | Part of Plant Used and Herbal Preparation | Traditional Medicinal Uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. aculeatum Vent. From West to East Africa via the Sudano-Sahelian belt | Water decoctions of aerial parts and roots | Tuberculosis, laxatives, venereal diseases, leprosy, skin infections, colic, diarrhea, intestinal disorders, wounds, gastritis, eye treatments, stomach troubles | [63,64,65,66] |

| C. adenogonium Steud ex A. Rich. syn. C. fragrans F. Hoffm Widely distributed in tropical Africa from West to East Africa and south to Zimbabwe and Mozambique | Leaves, barks, and roots are used as decoctions, infusions and macerates | Diarrhea, leprosy, syphilitic sores, coughs, snakebites, wounds, sores, chest and abdominal pains, schistosomiasis, and fungal infections of the scalp | [17,36,44,65,66,67, 68] |

| C. apiculatum Sond. East, south, and southwestern Africa | Leaf extracts, leaf decoctions, and root decoctions | Stomach problems, disinfection of the navel after birth, venereal diseases, conjunctivitis, schistosomiasis, abdominal disorders, leprosy, and conjunctivitis | [66,69,70] |

| C. collinum Fresen. Widespread in dry savanna areas in tropical Africa. Occurs from Senegal to East Africa and south throughout southern Africa | Roots, boiled roots, barks, leaves, gum are used as decoctions; roots and twigs are chewed | Stomachache, purgative, diuretic, coughs, toothache, dysentery, snake bites, colds, chronic diarrhea, panaritium (nail bed inflammation), infertility, venereal diseases, sores, wounds, and malaria | [29,49,53,54,56,69,71] |

| C. erythrophyllum (Burch.) Sond. Native to southern African countries | Root, stem, and bark decoctions; dried powdered gum and leaves | Coughs, colds, leprosy, wounds and sores, prophylactic for venereal diseases, infertility, diarrhea, and dysentery | [29,35,60,61] |

| C. hartmannianum Schweinf. Horn of Africa, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia | Roots, leaves, stem bark, stem wood, macerations, decoctions, tonics, pastes, ointments, and smoke fumigant | Abdominal pain, sore throat, dysentery, fever, jaundice, sexually transmitted diseases, fungal nail infections, rheumatism, fatigue, skin diseases, acne, wounds, ulcer infections, leprosy, and bacterial infections | [64,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] |

| C. hereroense Shinz In tropical Africa from Angola in West Africa to the Sudan in East Africa, as well as growing on a strip from Kenya to Zimbabwe | Shrub, leaves, and crushed leaves are suspended in water and used as a cold infusion Roots, leaves, young shoots, and barks are used as decoctions | Headache, female infertility, gonorrea, chlamydia symptoms in men, coughs, stomach problems, chest problems, schistosomiasis, abdominal ulcers, wounds, malaria, leprosy, and toncillitis | [35,51,53,54,69,71,79] |

| C. imberbe Wawra Occurs mainly in African countries south of the equator | Powdered roots, leaves or bark are used as decoctions; the smoke of burnt leaves is inhaled; leaves are chewed; infusions of leaves and roots are taken orally; and ashes of the wood are used as toothpaste | Stomach problems and diarrhea, colds, coughs and chest pains, sexually transmitted infections, malaria, bilharzia, female infertility, leprosy, viral, bacterial and fungal infections, and toothpaste | [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,80] |

| C. kraussii Hochst syn. C. nelsonii Duemmer | Leaf extracts, roots, and leaves | Bacterial respiratory diseases and wound healing | [22,81,82,83] |

| C. micranthum G. Don West African savanna region | Leaves, seeds, stem bark and roots are used as dried powders and decoctions, juice is made from fresh roots, root powder, and fruit (dried and fresh), steam baths, and infusions or tea | Wounds, burns, insect stings, nausea, coughs, bronchitis, fever, toothache, malaria, massage, sores, diuretic, diarrhea, ointment, treatment of bruises, colds, vomiting, and gastrointestinal problems | [20,45,47,48,49,53,54,84,85] |

| C. molle R. Br. ex G. Don Throughout tropical Africa and the Arabian Peninsula | Barks, roots, leaves, infusions, and twigs | Dental caries and bad smell, wound dressing, skin disorders, dysentery, snakebite, coughs, pneumonia, fever, inhalant for chest complaints, tuberculosis, leprosy, dysentery, stomach problems, edema, worms, gonorrhea, syphilis, venereal diseases, malaria and HIV, extracts of leaves inhaled as steam bath, and peeled twigs as chewing sticks | [13,35,36,37,40,41,42,43,59,69,70,86] |

| C. nigricans Lepr. ex Guill. et Perr. Sénégal, Mauretania, Niger, Burkina Faso | The gum exudated from the bark and roots | Gastrointestinal disorders, enteralgia (colic), stomach problems, acne, jaundice, arthritis, rheumatism, cataract, conjunctivitis, headaches, and malaria | [64,80,87,88] |

| C. padoides Engl. & Diels Tropical and south-eastern Africa | Leaves, roots, crushed leaves, decoctions, and water extracts | Snakebites, wounds, hookworms, malaria, diarrhea, conjuctivitis, and bacterial and fungal infections | [69,80,88,89] |

| C. pentagonum M. A. Lawson syn. C. lasiopetalum Engl. & Diels South-East Kenya to South Tropical Africa | Roots, leaves | Wounds, edema, gonorrhea, loose tooth, and bleeding gums | [71] |

| C. psidioides Welw Angola, Namibia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe | Decoction of roots; fresh, pounded leaves mixed with porridge; and in combination with C. molle and C. zeyheri | Diarrhea, oedema, and back and muscle pains | [36] |

| C. zeyheri Sond. From Kenya to eastern DR Congo and northern Namibia to north-eastern South Africa | Barks, roots, leaves, the smoke of burnt leaves, decoctions, water extracts | Smallpox, nose bleeding, hemorrhoids, diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, coughs, toothaches, bacterial and fungal infections, scorpion bite, dry wounds, schistosomiasis, and eye inflammation | [17,35,51,59,69] |

| P. hylodendron Mildbr. West and Central Africa, Cameroon | Decoctions of stem bark, leaf sap | Measles, chickenpox, sexually transmitted diseases, female sterility, liver and kidney disorders, and epilepsy | [90,91] |

| P. myrtifolia (Laws.) Engl. & Diels Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Angola, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa | Root, stem bark and leaves are used as decoctions, macerations and baths, leaf sap, soup of roots cooked with chicken, leaf sap mixed with leaf sap of Diospyros zombensis (B.L. Burtt) F. White, leaves and fruits as vegetables | Venereal diseases, sores, wounds, dysentery, menorrhagia, swellings of the stomach, wounds, muscle pain, and diarrhea | [17,92,93,94] |

| P. suberosa Engl. & Diels West Africa; Mali, Senegal, Guinea, Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria | Leaves, leafy twig infusions, root decoctions, roasted pulverized root is used topically for headache, extracts of chopped roots and young shoots, stem bark, and young branches are used as chew sticks Called “Terenifu” in Malian traditional medicine | Meningitis, convulsive fever, headache, jaundice, dysentery, dermatitis, stomachache, gastric ulcers, purgative, toothache, hemorrhoids, conjunctivitis, trachoma, gastrich ulcers, cataract, cough medicine, sexually transmitted diseases, hemorrhoids, viral diseases, and candidiasis | [24,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104] |

3.2. The Genus Pteleopsis

3.2.1. Botany

3.2.2. Ethnopharmacology

4. Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties

4.1. Antibacterial and Antifungal Effects of Combretum spp. Extracts

| Plant Extracts | MIC/IZ/IZD | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| C. acutifolium Exell. (leaf) Acetone, hexane, DCM, and methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.02–2.5 mg/mL against C. albicans, C. neoformans, A. fumigatus, S. schenckii, and M. canis. | [108] |

| C. acutifolium (leaf) Methanol extract | MIC range: 0.15–1.50 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C.adenogonium Steud ex A.Rich syn. C. fragrans F. Hoffm. (leaf) Water, methanol, and n-hexane | MIC values: 1 mg/mL (B. cereus, K. pneumoniae), 0.01562 mg/mL (B. cereus), and 0.25 mg/mL (S. aureus). | [116] |

| C. fragrans F. Hoffm. syn. C. adenogonium (leaf) Ethanol extracts | MIC 0.25–4 mg/mL (Candida species) MIC between 0.5 and >4 mg/mL (Filamentous micromycetes). | [117] |

| C. fragrans F. Hoffm. syn. C. adenogonium (root) Methanol extracts | IZD between 0 and 38 mm (Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and Candida albicans). Best result: 38 mm against Micrococcus luteus. | [36] |

| C. fragrans syn. C. adenogonium (root) Methanol extracts | Antifungal against Candida albicans, C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and Cryptococcus neoformans. Best result against C. glabrata: IZD 26 mm. | [17] |

| C. adenogonium (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC 0.625 mg/mL (E. coli) | [118] |

| C. albopunctatum Suess. (leaf) Acetone and hexane extracts | MIC 0.08 mg/mL (C. neoformans and A. fumigatus). | [108] |

| C. albopunctatum (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.75–3 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. albopunctatum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values ranging between 0.02 and 0.64 mg/mL against C. albicans, C. neoformans, M. canis, S. schenckii, and A. fumigatus. | [83] |

| C. albopunctatum (leaf, stem bark) Water extracts | Stem bark and leaf extracts inhibit the QS-dependent production of violacein and pyocyanin in Chromobacterium violaceae and P. aeruginosa. | [119] |

| C. apiculatum Sond. subsp. apiculatum (leaf) Ethanol and water extracts | MIC values of ethanol extracts: 0.049 mg/mL against B. subtilis and S. aureus. MIC values of water extracts: 0.39 mg/mL against B. subtilis and S. aureus. | [120] |

| C. apiculatum ssp. apiculatum (leaf) DCM, methanol, and acetone | MIC 0.04 mg/mL (C. albicans and C. neoformans), | [108] |

| C. apiculatum subsp. apiculatum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC 1.6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.4 mg/mL (S. aureus), 0.8 mg/mL (E. coli), and 0.8 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. bracteosum (Hochst.) Engl. & Diels (leaf) DCM, methanol, and hexane | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. neoformans) MIC 0.02 mg/mL (S. schenckii) | [108] |

| C. bracteosum(Hochst.) Brandis (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.50–3.00 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. caffrum (Eckl. & Zeyh.) Kuntze (leaf) Hexane and DCM extracts | MIC 0.16 mg/mL (C. albicans, C. neoformans). | [108] |

| C. caffrum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.8 mg/mL (S. aureus), 1.6 mg/mL (E. coli), and 0.4 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. caffrum (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.63–2.50 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. celastroides ssp. celastroides Welw. ex M.A. Lawson (leaf) DCM, methanol, acetone, and hexane extracts | MIC range between 0.02 and >2.5 mg/mL C. albicans, C. neoformans, A. fumigatus, Sporotrichum schenkii, and Microsporum canis. Best results: DCM 0.08 mg/mL (C. neoformans); acetone and MeOH 0.02 mg/mL (M. canis). | [108] |

| C. celastroides ssp. celastroides (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 3.0 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.8 mg/mL (S. aureus), 3.0 mg/mL (E. coli), and 1.6 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. celastroides ssp. orientale (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 1.6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 1.6 mg/mL (S. aureus), 3.0 mg/mL (E. coli), and 0.8 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. celastroides subsp. celastroides and C. celastroides subsp. orientale (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.50–3.00 mg/mL and 0.25–3.00 mg/mL, respectively, against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. collinum ssp. Suluense (Engl. & Diels) Okafor (leaf) Acetone and DCM | MIC values: 0.08 mg/mL (C. albicans and C. neoformans). | [108] |

| C. collinum ssp. Taborense (Engl.) Okafor (leaf) Acetone, DCM extracts | MIC values: 0.08 mg/mL (C. neoformans) and 0.64 mg/mL (C. albicans). | [108] |

| C. collinum Fresen. (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 0.13 mg/mL (S. aureus), 0.07 mg/mL (E. coli), 0.08 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), and 0.100 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [121] |

| C. collinum (fruits, leaves, roots) Methanol extracts | No activity against Candida spp. or Cryptococcus neoformans, with the exception of a leaf MeOH extract against C. krusei (IZD 18.4 mm). | [17] |

| C. edwardsii Exell (leaf) Acetone and methanol extracts | MIC 0.04 mg/mL (C. albicans). | [108] |

| C. edwardsii (leaf) Ethyl acetate fraction, DCM, hexane, and water fractions | MIC range from 0.390–3.125 mg/mL against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus. | [30] |

| C. eleagnoides Klotzsch (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC 0.05 mg/mL against B. cereus and a low average MIC value of 0.52 mg/mL against the other bacteria used in the screenings. | [109] |

| C. erythrophyllum (Burch.) Sond. (leaf) Ethyl acetate and acetone extracts | MIC 0.04 mg/mL (Fusarium spp.). | [19] |

| C. erythrophyllum (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC 3.875 mg/mL (C. albicans, A. niger). | [29] |

| C. erythrophyllum (leaf) Acetone, methanol, DCM extracts | MIC values: 0.02 mg/mL (M. canis), 0.32 mg/mL (C. neoformans, S. schenckii, and M. canis). | [108] |

| C. erythrophyllum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 3.0 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.8 mg/mL (S. aureus), 1.6 mg/mL (E. coli), and 1.6 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. erythrophyllum (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.50–2.50 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. erythrophyllum (leaf) Water, CHCl3, butanol, 35% water in methanol, and CCl4 bioautography | MIC 0.05–25 mg/mL of solvent partition fractions against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis and E. coli Best result for a 35% water extract in MeOH against S. aureus (MIC 0.05 mg/mL); a chloroform fraction contained the highest number of antibacterial compounds. | [114] |

| C. hartmannianum (Schweinf) (bark) DCM, ethyl acetate, ethanol | MIC values of 12.5, 25 and 1.56 mg/mL, respectively, against Mycobacterium aurum A+. | [112] |

| C. hartmannianum (bark) Methanol, 50% ethanol | MIC values of 0.5 and 1 mg/mL, respectively, against Porphyromonas gingivalis. | [122] |

| C. hartmannianum (fruit) Water extracts | MIC 1.91 mg/mL, and IZD 20 and 19 mm against B. subtilis and S. aureus, respectively. | [74] |

| C. hartmannianum (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC 1.43 mg/mL, IZD 30 mm against B. subtilis. | [74] |

| C. hartmannianum (leaf) DCM, ethyl acetate, ethanol | MIC values of 0.78, 3.12 and 0.19 mg/mL, respectively, against Mycobacterium aurum A+. | [112] |

| C. hartmannianum (root) Ethanol extracts | MIC 0.2 mg/mL (E. coli, S. aureus). | [75] |

| C. hartmannianum (root) | MIC 0.313 and 0.625 mg/mL, respectively, of a methanol and ethyl acetate extract of the root against Mycobacterium smegmatis. | [76] |

| C. hereroense Schinz (leaf) Acetone, methanol, DCM and hexane extracts | MIC values of 0.02 mg/mL (Cryptococcus neoformans), 0.02–0.32 mg/mL (Candida albicans), and 0.02–0.04 mg/mL (Microsporum canis). | [108] |

| C. hereroense (leaf) Hexane, DCM, acetone and methanol extracts | MIC values of 1.25, 0.62, 0.47 and 1.90 mg/mL, respectively, against Mycobacterium smegmatis. | [113] |

| C. hereroense (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 1.6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 3.0 mg/mL (S. aureus), 3.0 mg/mL (E. coli), and 1.6 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. hereroense (leaf) Methanol extracts Water extracts | MIC values: 5.075 mg/mL (A. niger), 4.486 mg/mL (C. albicans), 0.395 mg/mL (Rhizopus stolonifer), 0.240 mg/mL (Proteus vulgaris), and 0.287 mg/mL (Proteus vulgaris and Rhizopus stolonifer). | [29] |

| C. hereroense (stem) Methanol extracts | MIC values: 30.0 mg/mL (S. epidermidis) and 23.3 mg/mL (Sarcina sp.). | [36] |

| C. imberbe Wawra (leaf) Hexane, DCM | MIC 0.16 mg/mL (C. albicans and C. neoformans). | [108] |

| C. imberbe (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 2.5 mg/mL (C. albicans), 0.16 mg/mL (C. neoformans), 0.04 mg/mL (M. canis), and 2.5 mg/mL (S. schenckii, A. fumigatus). | [83] |

| C. imberbe (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.05–0.75 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. imberbe (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 3.0 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 1.6 mg/mL (S. aureus), 3.0 mg/mL (E. coli), and 1.6 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. imberbe (leaf) Ethanol extracts | MIC 0.125 mg/mL (Mycobacterium smegmatis). | [51] |

| C. kraussii Hochst (bark) Ethyl acetate, ethanol, and aqueous extracts | MIC values between 0.6–9.0 mg/mLagainst B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae. | [123] |

| C. kraussii (leaf) Hexane extracts | MIC 0.08 mg/mL (C. albicans) | [108] |

| C. kraussii (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 1.6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.8 mg/mL (S. aureus, E. faecalis), and 1.6 mg/mL (E. coli). | [107] |

| C. kraussii (leaf) Ethyl acetate fraction, DCM, hexane fraction, and water fractions | MIC range from 0.390 to 1.560 mg/mL against E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. aureus. | [30] |

| C. kraussii (root) Ethyl acetate, ethanol, and aqueous extracts | MIC values between 0.195–3.125 mg/mLagainst B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae. | [123] |

| C. micranthum G. Don (root, stem bark and leaves) Water and methanol extracts | Agar diffusion IZD results: All root, bark, and stem bark extracts showed a strong growth inhibition of clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa at a level significantly higher than ampicillin, gentamycin, and ciprofloxacin. Hot-water extracts of the root bark inhibited the growth of clinical strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. The root and stem bark extracts were more active than extracts of the leaves. | [124] |

| C. micranthum (leaf) Ethanol extracts | Active at 1 mg/mL and 5 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa and S. aureus) and at 5 mg/mL against C. albicans (IZ from 8 to 11 mm). MIC 0.5 mg/mL of an ethanol extract of the leaves against S. aureus. | [84] |

| C. micranthum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC 310 µg/mL (Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides). | [125] |

| C. micranthum (stem bark) A 70% EtOH extract and its solvent partition fractions; n-hexane, chloroform, and aqueous | 70% EtOH extract and aqueous fraction: MIC 230 µg/mL (E.coli), MIC 470 µg/mL (P. aeruginosa), and MIC 940 µg/mL (S. aureus). n-hexane fraction: MIC 7.5 mg/mL (S. aureus, E. coli), and 15 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa). chloroform fraction: MIC 1880 µg/mL (S. aureus, B. subtilis, and E. coli). | [126] |

| C. microphyllum Klotzsch(leaf) Acetone, methanol, DCM, and hexane extracts | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. neoformans) | [108] |

| C. microphyllum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 1.6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.4 mg/mL (S. aureus), 0.8 mg/mL (E. coli), and 0.8 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. microphyllum (leaf) Methanol extracts | 3.9 mg/mL (A. niger), 1.008 mg/mL (C. albicans), and 0.494 mg/mL (R. stolonifer). | [29] |

| C. microphyllum (leaf) Acetone and 1% aqueous sodium bicarbonate, hexane, ethyl ether, methylene dichloride, tetrahydrofuran, acetone, ethanol, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water. | MIC against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. coli and E. faecalis varied from 0.08 to 1.20 mg/mL for the different extracts, with hexane providing the lowest MIC of 0.08 mg/mL against E. faecalis. The water extract was not as active as the other extracts (MIC 1.20 mg/mL). | [127] |

| C. moggii Excell (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. albicans and C. neoformans). | [108] |

| C. moggii (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC 3.0 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.8 mg/mL (S. aureus), 1.6 mg/mL (E. coli), and 1.6 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. molle R. Br. ex. G. Don. (stem bark) Acetone extracts | MIC 0.050 mg/mL (Shigella spp., E. coli) | [43] |

| C. molle (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC 0.625 mg/mL (E. coli) | [118] |

| C. molle (leaf) Ethyl acetate and acetone extracts | MIC 0.04 mg/mL (Fusarium spp.) | [19] |

| C. molle (leaf) Ethyl alcohol:H2O (50:50) | MIC 0.25 mg/mL (Microsporum, Trichophyton) | [46] |

| C. molle (leaf) Acetone, methanol, DCM and hexane | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. neoformans) | [108] |

| C. molle (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC 0.160 mg/mL (Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides) | [125] |

| C. molle (leaf) Methanol extracts | IZD 0–30 mm. Best results: 30 mm against Micrococcus luteus, 25 mm against Enterobacter aerogenes, and 25 mm against Sarcina sp. | [36] |

| C. molle (root) Methanol extracts | MIC 1.00 mg/mL (S. aureus) A decoction was inactive. | [128] |

| C. molle (stem bark) Ethanol extracts | MIC 0.250 mg/mL (B. cereus) | [129] |

| C. molle (stem bark) Acetone extracts | MIC 1.000 mg/mL (M. tuberculosis) | [111] |

| C. molle (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC 0.040 mg/mL against Penicillium janthinellum. | [130] |

| C. molle (root) Methanol extracts | Antifungal against all Candida spp. used in the screening and Cryptococcus neoformans. Best activity against C. glabrata (IZD 25.8 mm) | [17] |

| C. mossambicense (Klotzsch) (leaf) Methanol and hexane extracts | Active against yeasts, dimorphic fungi and moulds at MIC values between 0.02 and 2.5 mg/mL. Lowest MIC values: 0.04 mg/mL of a methanol extract (C. albicans); 0.02 mg/mL of acetone, dichloromethane and hexane extracts (M. canis); and 0.02 mg/mL of a hexane extract (C. neoformans). | [108] |

| C. mossambicense (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 0.800 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa, S. aureus), 1.600 mg/mL (E. coli), and 0.400 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. nelsonii Duemmer (Angustimarginata Engl. & Diels) syn. C. kraussii Hochst (leaf) Hexane extracts | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. neoformans) | [108] |

| C. nelsonii (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values between 0.02 and 0.16 mg/mL against C. albicans, C. neoformans, M. canis, S. schenckii and A. fumigatus. | [83] |

| C. nelsonii (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values of 3.0 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa), 0.8 mg/mL (S. aureus), 1.6 mg/mL (E. coli) and 6.0 mg/mL (E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. nigricans Lepr. (leaf) Ethyl alcohol–water (50:50, v/v) | MIC values between 1 and >4 mg/mL against C. albicans, Epidermophyton floccosum, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Trichophyton rubrum. | [46] |

| C. nigricans (entire root) Ethyl alcohol–water (50:50, v/v) | MIC between 0.25 and >4 mg/mL against C. albicans, Epidermophyton floccosum, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Trichophyton rubrum. | [46] |

| C. padoides Eng. & Diels (leaf) DCM and acetone extracts | MIC 0.32 mg/mL (C. albicans, C. neoformans) | [108] |

| C. padoides (leaf) 70% Acetone in acidified water (crude), water, hexane, ethyl acetate, and butanol fractions | MIC between 0.019 and 2.5 mg/mL against C. albicans, C. neoformans, A. fumigatus, E. coli, E. faecalis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa. MIC values of various extracts: Crude extract (70% acetone): 0.039 mg/mL (C. neoformans) Hexane fraction: 0.019 mg/mL (E. coli, E. faecalis, S. aureus) Ethyl acetate fraction: 0.019 mg/mL (C. neoformans) Butanol fraction: 0.019 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa) | [117] |

| C. padoides (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 0.800 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and E. faecalis), and 6.000 mg/mL (S. aureus). | [107] |

| C. padoides (root) Methanol extracts | Antifungal against all Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans. Best result against C. glabrata; IZD 29.1 mm MIC 6.25 mg/mL (C. glabrata and Cryptococcus neoformans) | [17] |

| C. padoides (stem bark) Crude methanol extract and a butanol fraction resulting from solvent partition of the MeOH extract | Lowest MIC: 1250 µg/mL of a methanol extract MIC of a butanol fraction: 2.5 mg/mL Test bacterium: Mycobacterium smegmatis | [23] |

| C. padoides (stem bark, root) Methanol | IZD range: 0–32 mm Best results: IZD 32 mm against Enterobacter aerogenes and 31 mm against S. aureus. Not active against E. coli. | [36] |

| C. paniculatum Vent. (leaf) Acetone, methanol, DCM and hexane extracts | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. neoformans) | [108] |

| C. paniculatum (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 1.6 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and E. faecalis), 0.8 mg/mL (E. coli). | [107] |

| C. paniculatum (root) Methanol, water extracts | MIC values: 2.77 mg/mL (S. epidermidis), 1.85 mg/mL (S. aureus), and 14.44 mg/mL (S. epidermidis, S. aureus). | [128] |

| C. pentagonum Laws. (fruit) Methanol extracts | MIC 3.44 mg/mL, IZD = 21 mm, (B. subtilis)MIC 6.87 mg/mL, IZD = 23 mm, (S. aureus) | [74] |

| C. pentagonum (bark) Water extracts | MIC 4.86 mg/mL, IZD = 18 mm, (B. subtilis) | [74] |

| C. petrophilum Retief. (leaf) Acetone, methanol, DCM, and hexane | MIC 0.02 mg/mL: acetone and methanol extracts against C. albicans and M. canis; acetone, hexane, dichloromethane, and methanol extracts against C. neoformans. | [108] |

| C. petrophilum (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.50– >3.00 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae | [109] |

| C. psidioides Welw. (stem bark and fruit) Methanol extracts | IZD 16.0–24.6 mm against C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and Cryptococcus neoformans | [17] |

| C. psidioides (leaf) Methanol extracts | IZD between 17–30 mm (diameter of hole: 12 mm) against S. aureus, E. aerogenes, S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, and C. albicans | [36] |

| C. psidioides (stem bark) Methanol extract and its n-butanol and chloroform fractions resulting from solvent partition | IZD range: 14–29.00 mm, with the crude methanol extract being the most active (IZD 29 mm). Lowest MIC: 625 µg/mL of a methanol extract. MIC 2500 µg/mL for the n-butanol and chloroform fractions. Test bacterium: M. smegmatis | [23] |

| C. woodii Duemmer (leaf) Hexane, DCM, methanol extracts | MIC values: 0.08 mg/mL (C. albicans and C. neoformans) and 0.02 mg/mL (Microsporum canis). | [108] |

| C. woodii (leaf) Crude water and methanol extracts | MIC values: 0.078 mg/mL (C. neoformans), 1.250 mg/mL (C. albicans), 0.156 mg/mL (E. faecalis), 0.625 mg/mL (E. coli, P. aeruginosa), and 0.312 mg/mL (S. aureus). | [117] |

| C. woodii (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.50–3.00 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. zeyheri Sond. (leaf) Methanol extracts | MIC range: 0.25–3.00 mg/mL against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| C. zeyheri (entire plant) | Active at 0.03 mg/mL against C. albicans and Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Screening with bioautography. | [131] |

| C. zeyheri (leaf) Water and methanol extracts | MIC 6 mg/mL against E. coli and B. subtilis. | [132] |

| C. zeyheri (leaf) Acetone and methanol extracts | MIC 0.02 mg/mL (C. albicans) MIC 0.08 mg/mL (C. neoformans) | [108] |

| C. zeyheri (leaf) Acetone extracts | MIC values: 0.80 mg/mL (P. aeruginosa and S. aureus) and 1.60 mg/mL (E. coli, E. faecalis). | [107] |

| C. zeyheri (stem bark, fruits, root) Methanol extracts | IZD between 0–33 mm. Micrococcus luteus: IZD was 33 mm for a stem bark methanol extract. | [36] |

4.1.1. Combretum molle

4.1.2. Combretum erythrophyllum

4.1.3. Combretum adenogonium

4.1.4. Combretum hartmannianum

4.1.5. Combretum zeyheri

4.1.6. Combretum micranthum

4.1.7. South African and Sudano-Sahelian Species of Combretum

4.2. Antibacterial and Antifungal Effects of Pteleopsis Species

4.2.1. Pteleopsis hylodendron

4.2.2. Pteleopsis habeensis

4.2.3. Pteleopsis suberosa

4.2.4. Pteleopsis myrtifolia

| Plant Extracts | MIC/IZ/IZD | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pteleopsis habeensis Aubrev ex Keay (stem bark) Methanol extracts | MIC/IZD against E. coli: 1.562 mg/mL (no growth), IZD 18–25 mm (at 12.5–100 mg/mL). MIC/IZD against S. aureus:1.562 mg/mL (no growth), IZD 18–24 mm (at 12.5–100 mg/mL). | [140] |

| Pteleopsis hylodendron Mildbr. (stem bark) Crude methanol extracts | MIC 0.781–12.5 mg/mL: E. coli, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, S. flexneri, S. paratyphi A/B, and S. typhi. MIC 0.781–3.125 mg/mL: E. faecalis, S. aureus. IZD against Gram-negative bacteria: 0.00–22.00 mm IZD against Gram-positive bacteria: 10.87–25.00 mm IZD against S. aureus (most sensitive): 20.00–25.00 mm | [139] |

| Pteleopsis hylodendron (stem bark) Ethyl acetate extract | Ethyl acetate extract of the stem bark active against Salmonella typhi, Corynebacterium diptheriae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Bacillus cereus. | [90] |

| Pteleopsis myrtifolia (M.A. Laws.) Engl. & Diels. (roots) Methanol extracts | IZD 21.2 mm against C. glabrata IZD 16.9–21.2 mm; C. albicans, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. neoformans. | [17] |

| Pteleopsis myrtifolia (leaves) Methanol extracts | Average MIC 1.85 mg/mL ± 0.88 mg/mL against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria; S. aureus, B. cereus, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, S. sonnei, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae. | [109] |

| Pteleopsis suberosa Engl. et Diels (stem bark) Methanol extracts ad decoctions | MIC-values: 0.03125–0.250 mg/mL and 0.0625–0.500 mg/mL, respectively, against Helicobacter pylori (ATCC 43504), and five clinical isolates of H. pylori. | [142] |

| Pteleopsis suberosa (stem bark and shoots/twigs) Ethyl alcohol–water (50:50, v/v) | MIC-values: 0.25–1 mg/mL (stem bark) and 0.25–2 mg/mL (shoot) against Candida albicans, Epidermophyton floccosum, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum. | [46] |

| Pteleopsis suberosa (stem bark) Methanol extracts | Antimicrobial activity against some microorganisms causing skin infections, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus capitis, S. epidermidis, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Pseudomonas cepacia. | [141] |

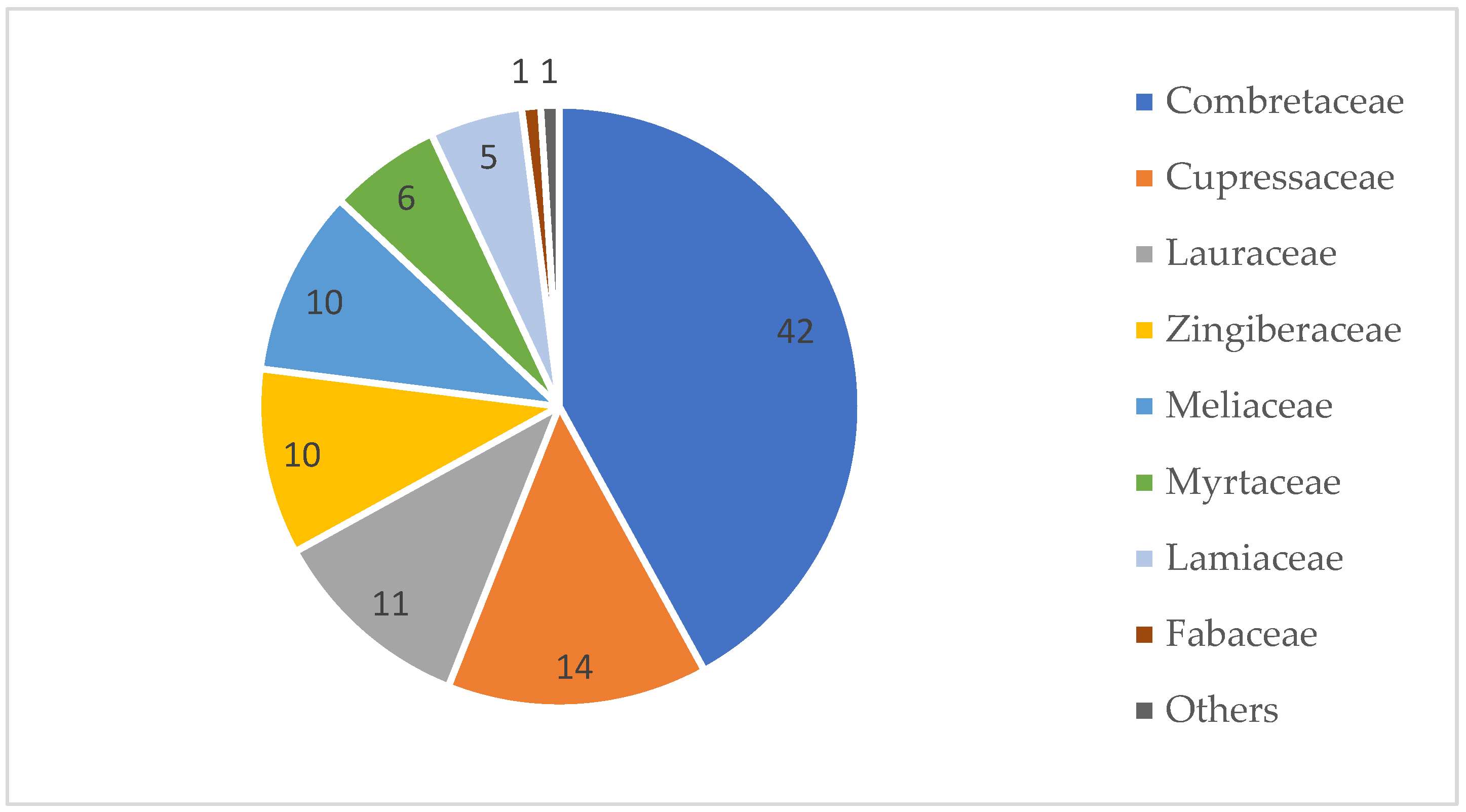

4.3. Antimicrobial Screenings Comparing Species Belonging to Two or More Genera of Combretaceae

5. Phytochemistry and Antimicrobial Compounds in Combretum and Pteleopsis spp.

5.1. Phytochemistry and Antimicrobial Compounds of Combretum Species

5.1.1. Triterpenes and Saponins

5.1.2. Flavonoids

5.1.3. Hydrolysable Tannins, Their Derivatives, and Condensed Tannins

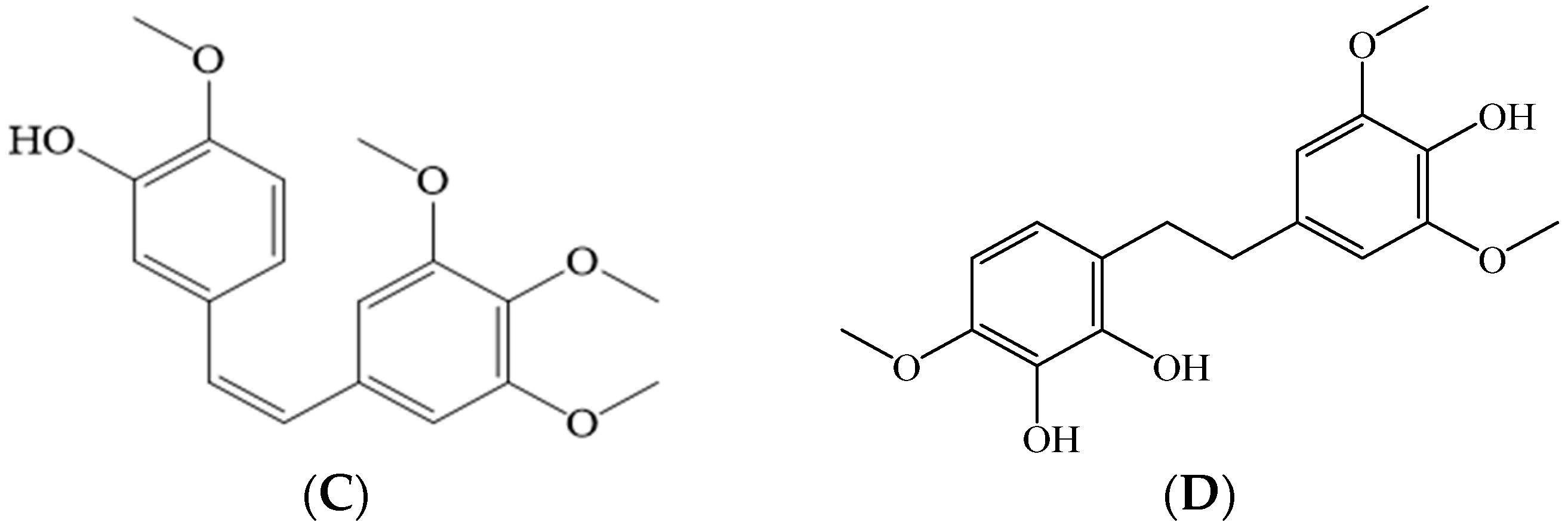

5.1.4. Stilbenoids (Bibenzyles and Phenanthrenes)

5.1.5. Cyclobutanes

5.1.6. Alkaloids

5.2. Phytochemistry and Antimicrobial Compounds of Pteleopsis Species

6. Potentiating Effects

6.1. Combination Effects of Combretum Species with Antibiotics and Other Plant Extracts

6.2. Nature and Significance of Interactions

6.3. Putting Synergies into Practice

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abadi, A.T.B.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Haertlé, T.; Blatt, N.L. World Health Organization Report: Current Crisis of Antibiotic Resistance. BioNanoScience 2019, 9, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seung, K.J.; Keshavjee, S.; Rich, M.L. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a017863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. World Health Organization, 2019: 2019 Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development: An Analysis of the Antibacterial Clinical Development Pipeline; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, L.; Sleiman, A.; Abdel-Massih, R.M. Antimicrobial activity of polyphenols and alkaloids in Middle Eastern plants. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rex, J.H.; Walsh, T.J.; Sobel, J.D. Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.C.; McBain, A.J.; Simões, M. Plants as sources of new antimicrobials and resistance-modifying agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.C.; Coqueiro, A.; Sultan, A.R.; Lemmens, N.; Kim, H.K.; Verpoorte, R.; Van Wamel, W.J.B.; Simões, M.; Choi, Y.H. Looking to nature for a new concept in antimicrobial treatments: Isoflavonoids from Cytisus striatus as antibiotic adjuvants against MRSA. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomoodally, M.F. Traditional medicines in Africa: An appraisal of ten potent African medicinal plants. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 617459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsobou, R.; Mapongmetsem, P.M.; Van Damme, P. Medicinal plants used for treating reproductive health care problems in Cameroon, Central Africa. Econ Bot. 2016, 70, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taofiq, O.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Hydroxycinnamic acids and their derivatives: Cosmeceutical significance, challenges and future perspectives, a review. Molecules 2017, 22, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.A.; Zolnik, C.P.; Molina, J. Leveraging phytochemicals: The plant phylogeny predicts sources of novel antibacterial compounds. Future Sci. 2019, 5, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eloff, J.N.; Katerere, D.R.; McGaw, L.J. The biological activity and chemistry of the southern African Combretaceae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaw, L.J.; Rabe, T.; Sparg, S.G.; Jäger, A.K.; Eloff, J.N.; Van Staden, J. An investigation of the biological activity of Combretum species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 75, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawe, A.; Pierre, S.; Tsala, D.E.; Habtemariam, S. Phytochemical constituents of Combretum Loefl. (Combretaceae). Pharm. Crops. 2013, 4, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordaan, M.; Van Wyk, A.E.; Maurin, O. A conspectus of Combretum (Combretaceae) in southern Africa, with taxonomic and nomenclatural notes on species and sections. Bothalia 2011, 41, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fyhrquist, P.; Mwasumbi, L.; Hæggström, C.-A.; Vuorela, H.; Hiltunen, R.; Vuorela, P. Antifungal activity of selected species of Terminalia, Pteleopsis and Combretum (Combretaceae) collected in Tanzania. Pharm. Biol. 2004, 42, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilney, P.M. A contribution to the leaf and young stem anatomy of the Combretaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2002, 138, 163–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seepe, H.A.; Amoo, S.O.; Nxumalo, W.; Adeleke, R.A. Sustainable use of thirteen South African medicinal plants for the management of crop diseases caused by Fusarium species—An in vitro study. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 130, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahate, S.; Hemke, A.; Umekar, M. Review on Combretaceae family. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2019, 58, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Gorai, D.; Acharya, R.; Roy, R. Combretum (combretaceae): Biological activity and phytochemistry. Indo Am. J. Pharm Res. 2014, 4, 5266–5299. [Google Scholar]

- Cock, I.E.; Van Vuuren, S.F. The traditional use of southern African medicinal plants for the treatment of bacterial respiratory diseases: A review of the ethnobotany and scientific evaluations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyhrquist, P.; Salih, E.Y.A.; Helenius, S.; Laakso, I.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R. HPLC-DAD and UHPLC/QTOF-MS analysis of polyphenols in extracts of the African Species Combretum padoides, C. zeyheri and C. psidioides related to their antimycobacterial activity. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pasquale, R.; Germano, M.P.; Keita, A.; Sanogo, R.; Iauk, L. Antiulcer activity of Pteleopsis suberosa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1995, 47, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanò, M.P.; D’Angelo, V.; Biasini, T.; Miano, T.C.; Braca, A.; De Leo, M.; De Pasquale, R.; Sanogo, R. Anti-Ulcer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of the n-butanol fraction from Pteleopsis suberosa stem bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeh, J.E.; Huang, X.; Sattler, I.; Swan, G.E.; Dahse, H.; Härtl, A.; Eloff, J.N. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of four known and one new triterpenoid from Combretum imberbe (Combretaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welch, C.; Zheng, J.; Bassène, E.; Raskin, I.; Simon, J.E.; Wu, Q. Bioactive polyphenols in kinkéliba tea (Combretum micranthum) and their glucose-lowering activities. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Morais Lima, G.R.; de Sales, I.R.; Caldas Filho, M.R.; de Jesus, N.Z.; de Sousa Falcão, H.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Cabral, A.G.; Souto, A.L.; Tavares, J.F.; Batista, L.M. Bioactivities of the genus Combretum (Combretaceae): A Review. Molecules 2012, 17, 9142–9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cock, I.E.; Van Vuuren, S.F. A comparison of the antimicrobial activity and toxicity of six Combretum and two Terminalia species from Southern Africa. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, 149740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chukwujekwu, J.C.; Van Staden, J. In vitro antibacterial activity of Combretum edwardsii, Combretum krausii, and Maytenus nemorosa and their synergistic effects in combination with antibiotics. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Komape, N.P.M.; Bagla, V.P.; Kabongo-Kayoka, P.; Masoko, P. Anti-mycobacterial potential and synergistic effects of combined crude extracts of selected medicinal plants used by Bapedi traditional healers to treat tuberculosis related symptoms in Limpopo Province, South Africa. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017, 17, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurib-Fakim, A. Medicinal plants: Traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006, 27, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu, C.; Ayyanar, M.; Raja, N.; Ignacimuthu, S. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzor, P.F.; Ebrahim, W.; Osadebe, P.O.; Nwodo, J.N.; Okoye, F.B.; Müller, W.E.G.; Lin, W.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. Metabolites from Combretum dolichopetalum and its associated endophytic fungus Nigrospora oryzae—Evidence for a metabolic partnership. Fitoterapia 2015, 105, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J.M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa Being an Account of Their Medicinal and Other Uses, Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Effects and Toxicology in Man and Animal, 2nd ed.; E & S. Livingstone Ltd.: Edinburgh, Scotland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fyhrquist, P.; Mwasumbi, L.; Hæggström, C.-A.; Vuorela, H.; Hiltunen, R.; Vuorela, P. Ethnobotanical and antimicrobial investigation of some species of Terminalia and Combretum (Combretaceae) growing in Tanzania. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 79, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasethe, M.T.; Semenya, S.S.; Maroyi, A. Medicinal plants traded in informal herbal medicine markets of the Limpopo province, South Africa. Evid. Based Compl. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 2609532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xavier, C.; Molina, J. Phylogeny of medicinal plants depicts cultural convergence among immigrant groups in New York City. J. Herb. Med. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelzer, G.H.; Gurib-Fakim, A. (Eds.) Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 11(1). Medicinal Plants 1; PROTA Foundation: Wageningen, The Netherlands; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands; CTA: Waningenen, The Netherlands, 2008; 791p. [Google Scholar]

- Anato, M.; Ketema, T. Anti-plasmodial activities of Combretum molle (Combretaceae) [Zwoo] seed extract in Swiss albino mice. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rademan, S.; Lall, N. Combretum molle. In Underexplored Medicinal Plants from Sub-Saharan Africa-Plants with Therapeutic Potential for Human Health; Academic Press, Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grønhaug, T.E.; Glæserud, S.; Skogsrud, M.; Ballo, N.; Bah, S.; Diallo, D.; Paulsen, B.S. Ethnopharmacological survey of six medicinal plants from Mali, West-Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 2008, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asres, K.; Mazumder, A.; Bucar, F. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of extracts of Combretum molle. Ethiop. Med. J. 2006, 44, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Augustino, S.; Gillah, P.R. Medicinal plants in urban districts of Tanzania: Plants, gender roles and sustainable use. Int. For. Rev. 2005, 7, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, C.R. Chemistry and Pharmacology of Kinkéliba (Combretum micranthum), a West African Medicinal Plant. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers University, Medicinal Chemistry, Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; 283p. [Google Scholar]

- Baba-Moussa, F.; Akpagana, K.; Bouchet, P. Antifungal activities of seven West African Combretaceae used in traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 66, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, F.; Valentin, A.; Pelissier, F.; Diafouka, F.; Marion, C.; Kone-Bamba, D.; Kone, M.; Mallie, M.; Yapo, A.; Bastide, J.-M. In vitro Antimalarial activity of vegetal extracts used in West-African traditional medicine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996, 54, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonkian, L.N.; Yerbanga, R.S.; Traoré/Coulibaly, M.; Lefèvre, T.; Sangaré, I.; Ouédraogo, T.; Traore, O.; Ouédraogo, J.B.; Guiguemde, T.R.; Dabiré, K.R. Plants against Malaria and Mosquitoes in Sahel region of Burkina Faso: An Ethno-botanical survey. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2017, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Keïta, J.N.; Diarra, N.; Kone, D.; Tounkara, H.; Dembele, F.; Coulibaly, M.; Traore, N. Medicinal plants used against malaria by traditional therapists in malaria endemic areas of the Ségou region, Mali. J. Med. Plants Res. 2020, 14, 480–487. [Google Scholar]

- Madikizela, B.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Antimycobacterial, anti-inflammatory and genotoxicity evaluation of plants used for the treatment of tuberculosis and related symptoms in South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwenzi, R.; Nyakunu, C.; Mukanganyama, S. The effect of selected Combretum species from Zimbabwe on the growth and drug efflux systems of Mycobacterium aurum and Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Microbial. Biochem. Technol. 2014, S3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ribeiro, A.; Romeiras, M.M.; Tavares, J.; Faria, M.T. Ethnobotanical survey in Canhane village, district of Massingir, Mozambique: Medicinal plants and traditional knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chinsembu, K.C.; Hedimbi, M. An ethnobotanical survey of plants used to manage HIV/AIDS opportunistic infections in Katima Mulilo, Caprivi region, Namibia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chinsembu, K.C.; Hijarunguru, A.; Mbangu, A. Ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional healers in the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic diseases in Rundu, Kavango East Region, Namibia. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 100, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinsembu, K.C. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora utilised by traditional healers in the management of sexually transmitted infections in Sesheke District, Western Province, Zambia. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheikhyoussef, A.; Shapi, M.; Matengu, K.; Ashekele, H.M. Ethnobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plant use by traditional healers in Oshikoto region, Namibia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dan, V.; Mchombu, K.; Mosimane, A. Indigenous medicinal knowledge of the San people: The case of Farm Six, Northern Namibia. Inf. Dev. 2010, 26, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzomba, P.; Chayamiti, T.; Nyoni, S.; Munosiyei, P.; Gwizangwe, I. Ferriprotoporphyrin IX-Combretum imberbe crude extracts interactions: Implication for malaria treatment. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 6, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, R.B.; Coates-Palgrave, K. Common Trees of the Highweld; Longman Rhodesia: Rhodesia, South Africa, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, N.D.; Katerere, D.R.; Eloff, J.N. Seven flavonoids with antibacterial activity isolated from Combretum erythrophyllum. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2004, 70, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawoza, T.; Ndove, T. Combretum erythrophyllum (Burch.) Sond. (Combretaceae): A review of its ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2015, 4, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Thulin, M. Flora of Somalia; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993; Volume 1, 501p. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad, K.M.; Sabry, M.M.; Elgayed, S.H.; El Shabrawy, A.-R.; El-Fishawy, A.M. Pharmacognostical Study of Combretum aculeatum Vent. Growing in Sudan. In Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy; Cairo University: Cairo, Egypt, 2019; Volume 57, No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, E.Y.A. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Antimicrobial Activity of Combretum, Terminalia and Anogeissus Species (Combretaceae) Growing Naturally in Sudan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2019. Tropical Forestry Reports 50. 193p. [Google Scholar]

- Diop, E.H.A.; Queiroz, E.F.; Marcourt, L. Antimycobacterial activity in a single-cell infection assay of ellagitannins from Combretum aculeatum and their bioavailable metabolites. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 238, 111832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerharo, J.; Adam, J.G. La Pharmacopée Sénégalaise Traditionelle- Plantes Médicinales et Toxiques; Frères, V., Ed.; Paris (France) Vigot: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens, G.E. Flora of Tropical East Africa. Combretaceae; East African Community, Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, London, UK, 1973; 99p. [Google Scholar]

- Dawé, A.; Mbiantcha, M.; Yakai, F.; Jabeen, A.; Ali, M.S.; Lateef, M.; Ngadjui, B.T. Flavonoids and triterpenes from Combretum fragrans with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antidiabetic potential. Z. Naturforsch. 2018, 73, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokwaro, J.O. Medicinal Plants of East Africa; East African Literature Bureau: Nairobi, Kenya, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, S.C.; Mahunnah, R.L.A.; Mshiu, E.N. Plants used in traditional medicine in Eastern Tanzania. II. Angiosperms (Capparidaceae to Ebenaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989, 25, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hedberg, I.; Hedberg, O.; Madati, P.J.; Mshigeni, K.E.; Mshiu, E.N.; Samuelsson, G. Inventory of plants used in traditional medicine in Tanzania. I. Plants of the families Acanthaceae-Cucurbitaceae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1982, 6, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.B.; Coombes, P.H. Acidic triterpene glycosides in trichome secretions differentiate subspecies of Combretum collinum in South Africa. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1999, 27, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, G.; Zerihun, M.; Solomon, Z. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Asgede Tsimbila district, Northwestern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2012, 10, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elegami, A.A.; El-Nima, E.I.; El Tohami, M.S.; Muddathir, A.K. Antimicrobial activity of some species of the family Combretaceae. Phytother Res. 2002, 16, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldeen, I.M.S.; Van Staden, J. In vitro pharmacological investigation of extracts from some trees used in Sudanese traditional medicine. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salih, E.Y.A.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Luukkanen, O.; Fahmi, M.K.M.; Fyhrquist, P. Hydrolyzable tannins (ellagitannins), flavonoids, pentacyclic triterpenes and their glycosides in antimycobacterial extracts of the ethnopharmacologically selected Sudanese medicinal plant Combretum hartmannianum Schweinf. 2021. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ghazali, G.E.B.; El Tohami, M.S.; El Egami, A.A. Medicinal Plants of the Sudan. Part III. Medicinal Plants of the White Nile Province; National Center for Research: Khartoum, Sudan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Muddathir, A.M.; Mitsunaga, T. Evaluation of anti-acne activity of selected Sudanese medicinal plants. J. Wood Sci. 2013, 59, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, G.; Farah, M.H.; Claeson, P.; Hagos, M.; Thulin, M.; Hedberg, O.; Alin, M.H. Inventory of plants used in traditional medicine in Somalia. I. Plants of the families Acanthaceae-Chenopodiaceae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 35, 25–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwinger, H.D. African Traditional Medicine: A Dictionary of Plant Use and Applications. With Supplement: Search System for Diseases; Medpharm: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000; 599p, Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20026790056 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Regassa, F.; Araya, M. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Combretum molle (Combretaceae) against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from crossbred dairy cows with clinical mastitis. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoko, P.; Mdee, L.K.; Mampuru, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. Biological activity of two related triterpenes isolated from Combretum nelsonii (Combretaceae) leaves. Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 22, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoko, P.; Picard, J.; Howard, R.L.; Mampuru, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. In vivo antifungal effect of Combretum and Terminalia species extracts on cutaneous wound healing in immunosuppressed rats. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abreu, P.M.; Martins, E.S.; Kayser, O.; Bindseil, K.-U.; Siems, K.; Seemann, A.; Frevert, J. Antimicrobial, antitumor and antileishmania screening of Medicinal Plants from Guinea-Bissau. Phytomedicine 1999, 6, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inngjerdingen, K.; Nergård, C.S.; Diallo, D.; Mounkoro, P.P.; Paulsen, B.S. An ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for wound healing in Dogonland, Mali, West Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 92, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van-Wyk, B.; Van-Wyk, P. Field Guide to Trees of Southern Africa; Struik Publishers: Cape Town, South Africa, 1997; 525p. [Google Scholar]

- Burkill, H.M. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa. In Combretum nigricans Lepr. [family COMBRETACEAE]; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, London, UK, 1985; Volume 1, p. 981. [Google Scholar]

- Chinedu, E.; Akah, P.A.; Jacob, D.L.; Onah, I.A.; Ukegbu, C.Y.; Chukwuemeka, C.K. Antimalarial activities of butanol and ethylacetate fractions of Combretum nigricans leaf. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2019, 9, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.S.; McGaw, L.J.; Elgorashi, E.E.; Naidoo, V.; Eloff, J.N. Polarity of extracts and fractions of four Combretum (Combretaceae) species used to treat infections and gastrointestinal disorders in southern African traditional medicine has a major effect on different relevant in vitro activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ngounou, N.F.; Atta-Ur-Rahman; Choudhary, M.I.; Malik, S.; Zareen, S.; Ali, R.; Lontsi, D. Two saponins from Pteleopsis hylodendron. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nana, H.M.; Ngane, R.A.N.; Kuiate, J.R.; Koanga Mogtomo, L.M.; Tamokoua, J.D.; Ndifor, F.; Mouokeu, R.S.; Ebelle Etame, R.M.; Biyiti, L.; Amvam Zollo, P.H. Acute and sub-acute toxicity of the methanolic extract of Pteleopsis hylodendron stem bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuel, L.; Bechel, A.; Noormahomed, E.V.; Hlashwayo, D.F.; Madureira, M.d.C. Ethnobotanical study of plants used by the traditional healers to treat malaria in Mogovolas district, northern Mozambique. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharani, N. Field Guide to Common Trees & Shrubs of East Africa, 3rd ed.; Alves, C., Ed.; Struik Nature: Western Cape, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Magwede, K.; van Wyk, B.; van Wyk, A.E. An inventory of Vhavenḓa useful plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, M.; De Tommasi, N.; Sanogo, R.; D’Angelo, V.; Germanó, M.P.; Bisignano, G.; Braca, A. Triterpenoid saponins from Pteleopsis suberosa stem bark. Phytochemistry. 2006, 67, 2623–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raliat, A.A.; Saheed, S.; Abdulhakeem, S.O. Pteleopsis suberosa Engl. and Diels (Combretaceae) aqueous stem bark extract extenuates oxidative damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. Pharmacogn. J. 2019, 11, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhavani, P.K.; Aik, W.T.; Basil, D.R. Pharmacology of traditional herbal medicines and their active principles used in the treatment of peptic ulcer, diarrhoea and inflammatory bowel disease. New Adv. Basic Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 14, 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Akintunde, J.K.; Babaita, A.K. Effect of PUFAs from Pteleopsis suberosa stem bark on androgenic enzymes, cellular ATP and keratic acid phosphatase in mercury chloride—Exposed rat. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2017, 22, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, T.; Myren, B.; Van Onselen, S. Ghana’s herbal market. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Izzo, A.A. The Plant Kingdom as a Source of Anti-ulcer Remedies. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.E.; Vestergaard, H.T.; Hansen, S.L.; Bah, S.; Diallo, D.; Jäger, A.K. Pharmacological screening of Malian medicinal plants used against epilepsy and convulsions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 121, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroz, D.; Towns, A.; Legba, S.I.; Swier, J.; Brière, S.; Sosef, M.; Van Andel, T. Quantifying the domestic market in herbal medicine in Benin, West Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanou, B.A.; Klotoe, J.R.; Fah, L.; Dougnon, V.; Koudokpon, C.H.; Toko, G.; Loko, F. Ethnobotanical survey on plants used in the treatment of candidiasis in traditional markets of southern Benin. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsoba, H.; Deschamps, J.-P. Use of medicinal plants for the treatment of oral diseases in Burkina Faso. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 104, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Amin, H.E. Trees and Shrubs of the Sudan; Ithaea Press: Exeter, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Von Maydell, H.J. Trees and Shrubs of the Sahel, Their Characteristics and Uses (No. 196); TZ Verlagsgesellschaft, GTZ: Germany, 1986; ISBN 3880853185. [Google Scholar]

- Eloff, J.N. The antibacterial activity of 27 Southern African members of the Combretaceae. S. Afr. J. Sci. 1999, 95, 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Masoko, P.; Picard, J.; Eloff, J.N. The antifungal activity of twenty-four southern African Combretum species (Combretaceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anokwuru, C.P.; Sandasi, M.; Chen, W.; Van Vuuren, S.; Elisha, I.L.; Combrinck, S.; Viljoen, A.M. Investigating antimicrobial compounds in South African Combretaceae species using a biochemometric approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 269, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, N.; Meyer, J.J.M. In vitro inhibition of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by ethnobotanically selected South African plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 66, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asres, K.; Bucar, F.; Edelsbrunner, S.; Kartnig, T.; Höger, G.; Thiel, W. Investigations on Antimycobacterial Activity of Some Ethiopian Medicinal Plants. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldeen, I.M.S.; Van Staden, J. Cyclooxygenase inhibition and antimycobacterial effects of extracts from Sudanese medicinal plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2008, 74, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masoko, P.; Nxumalo, K.M. Validation of antimycobacterial plants used by traditional healers in three districts of the Limpopo Province (South Africa). Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 586247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martini, N.D.; Eloff, J.N. The preliminary isolation of several antibacterial compounds from Combretum erythrophyllum (Combretaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998, 62, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, A.M.; Castro, R.H.A.; Cordeiro, R.P.; Sobrinho, T.J.S.P.; Castro, V.T.N.A.; Amorim, E.L.C.; Xavier, H.S.; Pisciottano, M.N.C. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial and toxicity properties of extracts of Schinopsis brasiliensis Engl. (Anacardiaceae). Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 5, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maregesi, S.M.; Pieters, L.; Ngassapa, O.D.; Apers, S.; Vingerhoets, R.; Cos, P.; Berghe, D.A.V.; Vlietinck, A.J. Screening of some Tanzanian medicinal plants from Bunda district for antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batawila, K.; Kokou, K.; Koumaglo, K.; Gbeassor, M.; de Foucault, B.; Bouchet, P.; Akpagana, K. Antifungal activities of five Combretaceae used in Togolese traditional medicine. Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroumsia, T.; Saotoing, P.; Dawé, A.; Djaouda, M.; Ekaney, M.; Mua, B. The sensitivity of Escherichia coli to extracts of Combretum fragrans, Combretum micranthum and Combretum molle locally used in the treatment of diarrheal diseases in the Far-North Region of Cameroon. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Vandeputte, O.M.; Kiendrebeogo, M.; Rajaonson, S.; Diallo, B.; Mol, A.; El Jaziri, M.; Baucher, M. Identification of catechin as one of the flavonoids from Combretum albiflorum bark extract that reduces the production of quorum-sensing-controlled virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGaw, L.J.; Jager, A.K.; Van Staden, J. Antibacterial, anthelmintic and anti-amoebic activity in South African medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 72, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netshiluvhi, T.R.; Eloff, J.N. Influence of annual rainfall on antibacterial activity of acetone leaf extracts of selected medicinal trees. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 102, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohieldin, E.A.M.; Muddathir, A.M.; Mitsunaga, T. Inhibitory activities of selected Sudanese medicinal plants on Porphyromonas gingivalis and matrix metalloproteinase-9 and isolation of bioactive compounds from Combretum hartmannianum (Schweinf) bark. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eldeen, I.M.S.; Elgorashi, E.E.; Van Staden, J. Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-cholinesterase and mutagenic effects of extracts obtained from some trees used in South African traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 102, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh, I.P.; Nworu, C.S.; Eleazar, C.I.; Onyemelukwe, F.N.; Esimone, C.O. Antibacterial profile of extracts of Combretum micranthum G. Don against resistant and sensitive nosocomial isolates. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 2, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muraina, I.A.; Adaudi, A.O.; Mamman, M.; Kazeem, H.M.; Picard, J.; McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. Antimycoplasmal activity of some plant species from northern Nigeria compared to the currently used therapeutic agent. Pharm Biol. 2010, 48, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeem, A.A.; Ejikeme, U.C.; Okarafor, E.U. Antibacterial potentials of the ethanolic extract of the stem bark of Combretum micranthum G. Don and its fractions. J. Plant Stud. 2012, 1, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Kotze, M.; Eloff, J.N. Extraction of antibacterial compounds from Combretum microphyllum (Combretaceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2002, 68, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steenkamp, V.; Fernandes, A.C.; Van Rensburg, C.E. Antibacterial activity of Venda medicinal plants. Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyid, A.; Abebe, D.; Debella, A.; Makonnen, Z.; Aberra, F.; Teka, F.; Kebede, T.; Urga, K.; Yersaw, K.; Biza, T.; et al. Screening of some medicinal plants of Ethiopia for their anti-microbial properties and chemical profiles. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogashoa, M.M.; Eloff, J.N. Different Combretum molle (Combretaceae) leaf extracts contain several different antifungal and antibacterial compounds. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 126, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, A.M.; Khan, M.R.; Ndaalio, G.; Nkunya, M.H.H.; Wevers, H. Studies on the rationale of African traditional medicine. Part III. Preliminary screening of medicinal plants for antifungal activity. Pak. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 1978, 21, 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Masengu, C.; Zimba, F.; Mangoyi, R.; Mukanganyama, S. Inhibitory activity of Combretum zeyheri and its S9 metabolites against Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis and Candida albicans. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2014, 6, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maregesi, S.M.; Ngassapa, O.D.; Pieters, L.; Vlietinck, A.J. Ethnopharmacological survey of the Bunda district, Tanzania: Plants used to treat infectious diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 113, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapfunde, S.; Sithole, S.; Mukanganyama, S. In vitro toxicity determination of antifungal constituents from Combretum zeyheri. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nyambuya, T.; Mautsa, R.; Mukanganyama, S. Alkaloid extracts from Combretum zeyheri inhibit the growth of Mycobacterium smegmatis. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karou, D.; Dicko, M.H.; Simpore, J.; Traore, A.S. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of polyphenols from ethnomedicinal plants of Burkina Faso. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 823–828. [Google Scholar]

- Kola, K.A.; Benjamin, A.E. Comparative antimicrobial activities of the leaves of Combretum micranthum and C. Racemosum. Global J. Med. Sci. 2002, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banfi, S.; Caruso, E.; Orlandi, V.; Barbieri, P.; Cavallari, S.; Viganò, P.; Clerici, P.; Chiodaroli, L. Antibacterial activity of leaf extracts from combretum micranthum and guiera senegalensis (Combretaceae). Res. J. Microbiol. 2014, 9, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mokale Kognou, A.L.; Ngono Ngane, R.A.; Kuiate, J.R.; Koanga Mogtomo, M.L.; Tchinda Tiabou, A.; Mouokeu, R.S.; Biyiti, L.; Amvam Zollo, P.H. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of the methanolic extract of the stem bark of Pteleopsis hylodendron (Combretaceae). Chemother. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 218750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muhammad, S.L. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activities of crude methanolic extract of Pteleopsis Habeensis (Aubrev Ex Keay) stem bark against drug resistant bacteria and fungi. Int. J. Technol. Res. Appl. 2014, 2, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bisignano, G.; Germano, M.P.; Nostro, A.; Sanogo, R. Drugs used in Africa as Dyes: II. Antimicrobial activities. Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Germano, M.P.; Sanogo, R.; Guglielmo, M.; De Pasquale, R.; Crisafi, G.; Bisignano, G. Effects of Pteleopsis suberosa extracts on experimental gastric ulcers and Helicobacter pylori growth. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998, 59, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiyegoro, O.A.; Okoh, A.I. Use of bioactive plant products in combination with standard antibiotics: Implications in antimicrobial chemotherapy. J. Med. Plant Res. 2009, 3, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Khameneh, B.; Iranshahy, M.; Soheili, V.; Fazly Bazzaz, B.S. Review on plant antimicrobials: A mechanistic viewpoint. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eloff, J.N.; Famakin, J.O.; Katerere, D.R.P. Isolation of an antibacterial stilbene from Combretum woodii (Combretaceae) leaves. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 1167–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Songca, S.P.; Ramurafhi, E.; Oluwafemi, O.S. A pentacyclic triterpene from the leaves of Combretum collinum Fresen showing antibacterial properties against Staphylococcus aureus. Afr. J. Biochem. Res. 2013, 7, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerere, D.R.; Gray, A.I.; Nash, R.J.; Waigh, R.D. Antimicrobial activity of pentacyclic triterpenes isolated from African Combretaceae. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegel, K.H.; Rogers, C.B. The characterization of mollic acid 3ß-D-xyloside and its genuine aglycone mollic acid, two novel 1-α-hydroxycycloartenoids from Combretum molle. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1985, 1, 1711–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeh, J.E.; Huang, X.; Swan, G.E.; Möllman, U.; Sattler, I.; Eloff, J.N. Novel antibacterial triterpenoid from Combretum padoides [Combretaceae]. ARKIVOC 2007, ix, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gossan, D.P.A.; Alabdul Magid, A.; Yao-Kouassi, P.A.; Josse, J.; Gangloff, S.C.; Morjani, H.; Voutquenne-Nazabadioko, L. Antibacterial and cytotoxic triterpenoids from the roots of Combretum racemosum. Fitoterapia 2016, 110, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runyoro, D.K.B.; Srivastava, S.K.; Darokar, M.P.; Olipa, N.D.; Cosam, C.J.; Mecky, I.N.M. Anticandidiasis agents from a Tanzanian plant, Combretum zeyheri. Med. Chem. Res. 2013, 22, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegler, V.; Sendker, J.; Petereit, F.; Liebau, E.; Hensel, A. Bioassay-guided fractionation of a leaf extract from Combretum Mucronatum with anthelmintic activity: Oligomeric procyanidins as the active principle. Molecules 2015, 20, 14810–14832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, T.; Qin, B.; Gao, M.; Yin, Y.; Wang, C.; Zang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, T. Effects of epigallocatechin gallate on the cell-wall structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 2122–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, F.; Hatano, T.; Ito, H.; Taniguchi, S.; Takahashi, E.; Okamoto, K. Antibacterial effects of guava tannins and related polyphenols on Vibrio and Aeromonas species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 1934578 × 08003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerere, D.R.; Serage, A.; Eloff, J.N. Isolation and characterisation of antibacterial compounds from Combretum apiculatum subspecies apiculatum (Combretaceae) leaves. Suid-Afrik. Tydskr. Vir Nat. En Tegnol. 2018, 37, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Katerere, D.R.; Gray, A.I.; Nash, R.J.; Waigh, R.D. Phytochemical and antimicrobial investigations of stilbenoids and flavonoids isolated from three species of Combretaceae. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Cragg, G.M.; Herald, D.L.; Schmidt, J.M.; Lohavanijaya, P. Isolation and structure of combretastatin. Can. J. Chem. 1982, 60, 1374–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Singh, S.B. Isolation, structure, and synthesis of combretastatin A-2, A-3, and B-2. Can. J. Chem. 1987, 65, 2390–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Singh, S.B.; Niven, M.L.; Hamel, E.; Schmidt, J.M. Isolation, structure, and synthesis of combretastatins A-1 and B-1, potent new inhibitors of microtubule assembly, derived from Combretum caffrum. J. Nat. Prod. 1987, 50, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Singh, S.B.; Niven, M.L. Antineoplastic agents. 160. Isolation and structure of combretastatin D-1: A cell growth inhibitory macrocyclic lactone from Combretum caffrum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 8539–8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Singh, S.B.; Schmidt, J.M.; Nixen, M.L.; Hamel, E.; Lin, C.M. Isolation, structure, synthesis, and antimitotic properties of combretastatins B-3 and B-4 from Combretum caffrum. J. Nat. Prod. 1988, 51, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettit, G.R.; Singh, S.B.; Boyd, M.R.; Hamel, E.; Pettit, R.K.; Schmidt, J.M.; Hogan, F. Antineoplastic agents. 291. Isolation and synthesis of combretastatins A-4, A-5, and A-6. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 1666–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookes, K.B.; Doudoukina, O.V.; Katsoulis, L.C.; Veale, D.J.H. Uteroactive constituents of Combretum kraussii. S. Afr. J. Chem. 1999, 52, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mushi, N.F.; Innocent, E.; Kidukuli, A.W. Cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities of substituted phenanthrenes from the roots of Combretum adenogonium Steud Ex A. Rich (Combretaceae). J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, E.; Swinny, E. Substituted bibenzyls, phenanthrenes and 9, 10-dihydrophenanthrenes from the heartwood of Combretum apiculatum. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 1139–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letcher, R.M.; Nhamo, L.R.M.; Gumiro, I.T. Chemical constituents of the Combretaceae. Part II. Substituted phenanthrenes and 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes and a substituted bibenzyl from the heartwood of Combretum molle. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1972, 1, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerere, D.R.; Graya, A.I.; Kennedy, A.R.; Nash, R.J.; Waigh, R.D. Cyclobutanes from Combretum albopunctatum. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawe, A.; Kapche, G.D.W.F.; Bankeu, J.J.K.; Fawai, Y.; Ali, M.S.; Ngadjui, B.T. Combretins A and B, new cycloartane-type triterpenes from Combretum fragrans. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2016, 99, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.B.; Coombes, P.H. Mollic acid and its glycosides in the trichome secretions of Combretum petrophilum. Biochem. Sys. Ecol. 2001, 29, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.C.J.; da Silva, V.C.; Dall’Oglio, E.L.; Teixeira de Sousa, P. Flavonoids from Combretum lanceolatum pohl. Biochem. Sys. Ecol. 2013, 49, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandeputte, O.M.; Kiendrebeogo, M.; Rasamiravaka, T.; Stévigny, C.; Duez, P.; Rajaonson, S.; Diallo, B.; Mol, A.; Baucher, M.; El Jaziri, M. The flavanone naringenin reduces the production of quorum sensing-controlled virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbiology 2011, 157, 2120–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pfundstein, B.; El Desouky, S.K.; Hull, W.E.; Haubner, R.; Erben, G.; Owen, R.W. Polyphenolic compounds in the fruits of Egyptian medicinal plants (Terminalia bellerica, Terminalia chebula and Terminalia horrida): Characterization, quantitation and determination of antioxidant capacities. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1132–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Luo, M.; Fu, Y.; Zu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yao, L.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Y. Effect of corilagin on membrane permeability of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans. Phyther. Res. 2013, 27, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzini, P.; Arapitsas, P.; Goretti, M.; Branda, E.; Turchetti, B.; Pinelli, P.; Romani, A. Antimicrobial and antiviral activity of hydrolysable tannins. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Amakura, Y.; Yoshimura, M. Structural features and biological properties of ellagitannins in some plant families of the order Myrtales. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jossang, A.; Pousset, J.-L.; Bodo, B. Combreglutinin, a hydrolysable tannin from Combretum Glutinosum. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, J. Ellagitannins in Finnish Plant Species–Characterization, Distribution and Oxidative Activity. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Turku, Turku, Finland, 2015; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Hattas, D.; Riitta Julkunen-Tiitto, R. The quantification of condensed tannins in African savanna tree species. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, S.; Casanova, N.A.; Rufián Henares, J.Á.; Fernandez Miyakawa, M.E. Natural tannin wood extracts as a potential food ingredient in the food industry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 2836–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialonska, D.; Kasimsetty, S.G.; Schrader, K.K.; Ferreira, D. The effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) byproducts and ellagitannins on the growth of human gut bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8344–8349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V.; Tabopda, T.K.; Ngameni, B.; Nana, F.; Tshikalange, T.E.; Ngadjui, B.T. Antimycobacterial, antibacterial and antifungal activities of Terminalia superba (Combretaceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatano, T.; Kusuda, M.; Inada, K.; Ogawa, T.-O.; Shiota, S.; Tsuchiya, T.; Yoshida, T. Effects of tannins and related polyphenols on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, S.; Shimizu, M.; Sugiyama, J.; Morita, Y.; Mizushima, T.; Tsushiya, T. Mechanisms of action of Corilagin and Tellimagrandin I that remarkably potentiate the activity of beta-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004, 48, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.; Shiota, S.; Mizushima, T.; Ito, H.; Hatano, T.; Yoshida, T.; Tsuchiya, T. Marked potentiation of activity of β-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by corilagin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 3198–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taguri, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kouno, I. Antibacterial spectrum of plant polyphenols and extracts depending upon hydroxyphenyl structure. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puljula, E.; Walton, G.; Woodward, M.J.; Karonen, M. Antimicrobial activities of ellagitannins against Clostridiales perfringens, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus plantarum and Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2020, 25, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Bee, G. Invited review: Tannins as a potential alternative to antibiotics to prevent coliform diarrhea in weaned pigs. Animal 2020, 14, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatoprak, G.Ş.; Küpeli Akkol, E.; Genç, Y.; Bardakcı, H.; Yücel, Ç.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. Combretastatins: An overview of structure, probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.; Pandey, P.; Singh, S.; Negi, A.S.; Banerjee, S. Unveiling the future reservoir of anti-cancer molecule—Combretastatin A4 from callus and cell aggregate suspension culture of flame creeper (Combretum microphyllum): Growth, exudation and elicitation studies. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020, 143, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwikkard, S.; Zhou, B.-N.; Glass, T.E.; Sharp, J.L.; Mattern, M.R.; Johnson, R.K.; Kingston, D.G.I. Bioactive compounds from Combretum erythrophyllum. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letcher, R.M.; Nhamo, L.R.M. Chemical constituents of the Combretaceae. Part III. Substituted phenanthrenes, 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes, and bibenzyls from the heartwood of Combretum psidioides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1972, 1, 2941–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Singh, S.B.; Hamel, E.; Lin, C.M.; Alberts, D.S.; Garcia-Kendal, D. Isolation and structure of the strong cell growth and tubulin inhibitor combretastatin A-4. Experientia 1989, 45, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Nagwanshi, R.; Bakhru, M.; Bageriab, S. Stereoselective photodimerization and antimicrobial activities of heteroaryl chalcones and their photoproducts. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, J.; Simon, J.E.; Wu, Q. Total synthesis of novel skeleton flavan-alkaloids. Molecules 2020, 25, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinedu, N.P. Qualitative Phytochemical Screening, Anti-inflammatory and Haematological Effects of Alkaloid Extract of Combretum dolichopetalum Leaves. Asian Hematol. Res. J. 2020, 3, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Atta-ur-Rahman; Zareen, S.; Choudhary, M.I.; Akhtar, M.N.; Ngounou, F.N. A triterpenoidal saponin and sphingolipids from Pteleopsis hylodendron. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2400–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, T.C.; Kozjak-Pavlovic, V. Diverse facets of sphingolipid involvement in bacterial infections. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]