Abstract

Enterococcus hirae is a rare pathogen in human infections, although its incidence may be underestimated due to its difficult isolation. We describe the first known case of E. hirae infective endocarditis (IE), which involves the mitral valve alone, and the seventh E. hirae IE worldwide. Case presentation: a 62-year-old male was admitted to our department with a five-month history of intermittent fever without responding to antibiotic treatment. His medical history included mitral valve prolapse, recent pleurisy, and lumbar epidural steroid injections due to lumbar degenerative disc disease. Pre-admission transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed mitral valve vegetation, and Enterococcus faecium was isolated on blood cultures by MALDI-TOF VITEK MS. During hospitalization, intravenous (IV) therapy with ampicillin and ceftriaxone was initiated, and E. hirae was identified by MALDI-TOF Bruker Biotyper on three blood culture sets. A second TEE revealed mitral valve regurgitation, which worsened due to infection progression. The patient underwent mitral valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve and had an uncomplicated postoperative course; he was discharged after six weeks of IV ampicillin and ceftriaxone treatment.

1. Introduction

Enterococcus hirae is a known pathogen of some animal species, causing endocarditis in chickens, diarrhea in rats, mastitis in cattle, intra-abdominal infection in cats, and sepsis in birds [1]. The first documented case of a human infection dates back to 1988 and was reported by Gilad et al., who described the case of a 49-year-old patient with end-stage renal disease affected by E. hirae septicemia [2]. Since then, only a few human cases have been documented in the literature, such as urinary tract infections, infective endocarditis, bacteraemia, and biliary tract infections [1].

Although Enterococci are a frequent cause of infection in humans, only 0.4% to 3.03% are reported to be from E. hirae species; nevertheless, these data may be underestimated due to its difficult isolation, and its identification could increase using MALDI-TOF: a diagnostic system with a higher sensitivity level compared to previous ones [1,3].

We describe a case of mitral valve infective endocarditis (IE) in a 62-year-old male reviewing the previously reported cases of E. hirae IE.

2. Case Report

A 62-year-old male was admitted to our department for a five-month history of intermittent fever without responding to antibiotic treatment alongside weight loss, sweating, coughing, and fatigue.

His medical history included mitral valve prolapse causing severe regurgitation, recent pleurisy, and lumbar epidural steroid injections due to lumbar degenerative disc disease.

Twelve days before admission, a TEE performed for persistent fever showed one vegetation on the mitral valve posterior leaflet measuring 4 × 6 mm, and Enterococcus faecium was identified by MALDI-TOF VITEK MS on blood cultures. According to the 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases IE Criteria, with two major clinical criteria and two minor clinical criteria, the patient was diagnosed with infective endocarditis and was, therefore, admitted to our Department [4].

At admission, the patient was conscious with a body temperature of 38.5 °C, a pulse rate of 112/min, a respiratory rate of 20/min, oxygen saturation of 98% on room air, and blood pressure of 119/76 mm Hg. Laboratory investigation revealed a white cell count of 4900/microliters, a C-reactive protein of 37.8 mg/L, and procalcitonin of 0.173 μg/L.

On day 1, blood cultures were taken, and intravenous therapy with ampicillin 2 g q4h and ceftriaxone 2 g q12h was initiated, according to antibiotics sensitivity. A good clinical response was obtained, and the temperature was resolved after 24 h.

On the third day after admission, the three blood culture sets drawn on day 1 yielded positive for Enterococcus hirae (using MALDI-TOF Bruker Biotyper) with an antibiotic sensitivity profile (according to EUCAST clinical breakpoints v 13.1) the same as the one obtained on E. faecium identified before admission (Table 1). Antibiotic therapy was, therefore, confirmed, obtaining a clinical improvement and no growth on blood cultures collected on day 3.

Table 1.

E. faecium and E. hirae antibiograms with M.I.C. calculated by Vitek2.

An abdominal CT scan showed splenomegaly (longitudinal diameter 16.4 cm) and renal fascia thickening. The colonoscopy showed no pathologic findings.

On day 17, a TEE was repeated and showed a dilated left ventricle and mitral posterior leaflet prolapse, determining severe regurgitation. Moreover, two vegetations attached to the posterior mitral leaflet of 5 × 6 mm and 6 × 7 mm, respectively, were identified. Therefore, the patient underwent mitral valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve after four weeks of antibiotic treatment. Mitral valve leaflets cultures and blood cultures taken after surgery were negative.

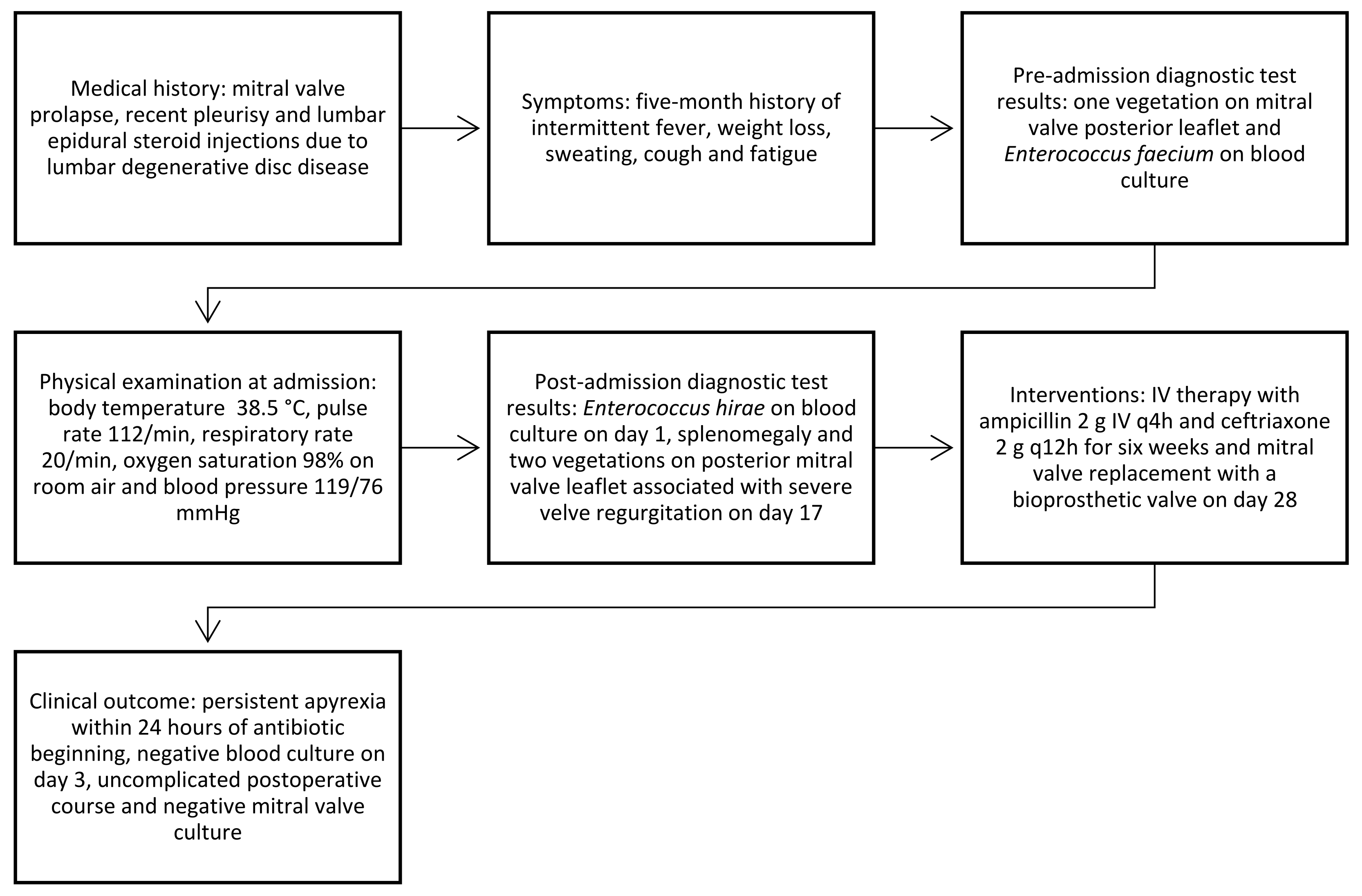

The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was discharged after a six-week IV ampicillin and ceftriaxone course. The timeline of clinical events is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of clinical events.

3. Literature Research

Online research without language restrictions was conducted using PubMed and SCOPUS. This research was performed by combining the terms endocarditis and Enterococcus hirae without limits. Furthermore, all references listed were hand-searched for other relevant articles.

The PubMed research identified 19 publications; their meticulous analysis led to 15 eligible articles, and no other articles (not present in PubMed) were found through the SCOPUS research. Overall, six articles describing the history of six patients, published between 2002 and 2020, were further evaluated.

Data regarding clinical characteristics, therapy, and the outcomes of the 6 patients were retrieved alongside that of our present case, which is analytically shown in Table 2. All patients were adults with a mean age of 66.3 years (56–78), and 3 out of 7 were females. Predisposing risk factors were present in 6 out of 7 patients, and none of them had a documented source of infection. Dual antibiotic therapy with two beta-lactams or one beta-lactam with aminoglycosides was administered for at least four weeks in all seven patients, five of which needed replacement valve surgery. All patients survived, although two of them had a relapse after the first treatment.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristic of patient with E. hirae IE.

4. Discussion

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a life-threatening disease associated with high mortality and severe complications. Enterococci are the third cause of infective endocarditis, after staphylococci and streptococci [11]. E. hirae is a member of the Enterococcus genus and is a well-documented cause of infection in animals (e.g., chickens, rats, cattle, cats, and psittacine birds) [1]. Otherwise, infection in humans is uncommon and could be secondary to contact with infected animals or the ingestion of contaminated food [12].

Although E. hirae is an important cause of endocarditis in broilers [12], our case is the seventh E. hirae IE in humans documented worldwide. Moreover, among the six previously described cases, five involved the aortic valve only, and one involving both the aortic and mitral valve. This is the first documented case of E. hirae IE involving only the mitral valve.

In the present case, the patient was affected by mitral valve prolapse with severe valve regurgitation. Predisposing risk factors for cardiac pathology were also present in five out of six previous patients, such as a history of coronary artery disease with percutaneous coronary intervention, aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve, cardiac arrhythmia with surgical ablation and patent foramen ovale, severe aortic regurgitation, severe aortic stenosis and the bicuspid aortic valve [5,6,7,8,9].

Although E. hirae is a common pathogen in animals, it is not documented as a clear E. hirae exposure in the previously reported cases nor in our one before symptom onset [5,6,7,8,9,10].

Four out of six previous cases of E. hirae IE had a history of gastrointestinal disease (colonic polyps with adenoma [6], gastric leiomyoma removal [7], cholecystectomy [9], colorectal cancer [10]); therefore the digestive tract may be the source of infection, as suggested by Winther M et al. [10]. In the present case, the patient had no GI symptoms or history of gastrointestinal disease, and the colonoscopy ruled out any local pathological involvement. The source of entry could be the lumbar epidural steroid injections the patient received a few months before the onset of symptoms due to lumbar degenerative disc disease or the ingestion of contaminated food.

The first blood culture taken before admission to our department identified E. faecium, whereas E. hirae was correctly identified to the species level through the three blood cultures drawn on day 1 of hospitalization in our department. In both cases, species identification was performed by mass spectrometry analysis MALDI-TOF MS (respectively, by VITEK MS and Bruker Biotyper).

Difficulties in the identification of E. hirae were also encountered in the first two documented cases of E. hirae IE, in which a rapid ID 32 Strep system misidentified the genus as E. durans and E. gallinarum. In both cases, E. hirae was subsequently and correctly identified using sodAint gene sequencing [5,6]. A case of native-valve bacterial endocarditis caused by Lactococcus garvieae, initially identified as E. hirae IE, was described as well [13].

In the other known E. hirae IE cases, species identification was performed by MALDI-TOF MS in cases four, five, and six, while it was unknown in the third.

MALDI-TOF MS proved to be an accurate system for the identification of both usual and unusual Enterococci with a high level of species-level discriminatory power [3]. The low rate of E. hirae incidence may have been the consequence of the limited power of other diagnostic systems; indeed, the identification of E. hirae increased after the development of MALDI-TOF MS [14]. Both the Bruker Biotyper and VITEK MS systems are able to correctly identify a wide range of bacteria; however, VITEK MS has a higher error rate compared to Bruker Biotyper in the case of unusual microorganisms [15], as corroborated by our case in which VITEK MS inaccurately identified the microorganism grown in the blood culture as E. faecium.

All seven patients survived E. hirae IE, five of which needed valve replacement surgery. The first two patients relapsed after treatment with ampicillin or amoxicillin and gentamicin, followed by rifampicin for six weeks. In the first case, vancomycin and gentamicin were administered for six weeks after relapse; in the second, the initial therapy was successfully repeated [5,6]. The third patient was treated with rifampin and ampicillin, followed by amoxicillin for a total of six weeks [7]. Ceftriaxone was administered in the fourth and fifth cases for six weeks, in combination with ampicillin in one case and with ampicillin, followed by penicillin G and then by a chronic suppressive therapy of oral penicillin in the other [8,9]. The sixth patient received benzylpenicillin for four weeks associated with gentamicin in the first two weeks [10]. In our case, six-weeks of therapy with ampicillin and ceftriaxone was administrated.

The European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a prolonged administration (up to 6 weeks) of synergistic bactericidal combinations of two cell wall inhibitors (ampicillin or penicillin and ceftriaxone for penicillin-susceptible strains) or one β-lactams with aminoglycosides for the management of enterococcal IE [16].

The susceptibility of E. hirae to antimicrobial agents suggests that this species is more similar to E. faecalis than E. faecium [14]. Treatment with ampicillin and ceftriaxone, with their synergism by inhibiting complementary PBPs, is as effective as ampicillin and gentamicin for E. faecalis IE [17,18]. Therefore, ampicillin plus ceftriaxone seems to be a good therapeutic alternative in E. hirae IE, reducing the risk of renal failure, which is typically associated with gentamicin administration [18].

In summary, E. hirae is a potential pathogen in severe human infections such as endocarditis; its incidence is expected to increase thanks to MALDI-TOF MS, an accurate system with a higher species-level discriminatory power than previous ones. Treatment with ampicillin and ceftriaxone for enterococcal IE is associated with a good prognosis and a low risk of side effects and could be a good therapeutic choice in E. hirae IE.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; Writing—review & editing, M.T., S.T., R.V., F.F., V.A. and A.C.; Conceptualization, R.G. and M.T.; Investigation, R.G. and A.C.; Resources, S.T., R.V. and V.A.; Supervision, A.C.; Funding Acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication costs of this article were covered by the Fund for VQR improvement assigned to the Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine, and Medical Specialties of the University of Palermo.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the retrospective nature of this case report and due to the fact that the patient’s data were anonymized, and no personal identification data were included.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Piccininiwe, D.; Bernasconi, E.; Di Benedetto, C.; Martinetti Lucchini, G.; Bongiovani, M. Enterococcus hirae infections in the clinical practice. Infect. Dis. 2023, 55, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilad, J.; Borer, A.; Riesenberg, K.; Peled, N.; Shnaider, A.; Schlaeffer, F. Enterococcus hirae septicemia in a patient with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1998, 17, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Chon, J.-W.; Jeong, H.-W.; Song, K.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Bae, D.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.-H. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Enterococcus isolates using MALDI-TOF MS and VITEK 2. AMB Expr. 2023, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, V.G.; Durack, D.T.; Selton-Suty, C.; Athan, E.; Bayer, A.S.; Chamis, A.L.; Dahl, A.; DiBernardo, L.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Duval, X.; et al. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Criteria for Infective Endocarditis: Updating the Modified Duke Criteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, ciad271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poyart, C.; Lambert, T.; Morand, P.; Abassade, P.; Quesne, G.; Baudouy, Y.; Trieu-Cuot, P. Native valve endocarditis due to Enterococcus hirae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2689–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talarmin, J.P.; Pineau, S.; Guillouzouic, A.; Boutoille, D.; Giraudeau, C.; Reynaud, A.; Lepelletier, D.; Corvec, S. Relapse of Enterococcus hirae prosthetic valve endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 1182–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghinah, R.; Watanabe, R.G.S.; Simabukuro, M.M.; Guariglia, C.; Pinto, L.F. Native valve endocarditis due to Enterococcus hirae presenting as a neurological deficit. Case Rep. Neurol. Med. 2013, 2013, 636070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebeling, C.G.; Romito, B.T. Aortic valve endocarditis from Enterococcus hirae infection. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2019, 32, 249–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkes, M.E.; White, C.; Wong, C.S. Native-Valve Enterococcus hirae endocarditis: A case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winther, M.; Dalager-Pedersen, M.; Tarpgaard, I.H.; Nielsen, H.L. First Danish case of infective endocarditis caused by Enterococcus hirae. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e237950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iung, B. Infective endocarditis. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and histopathology. Presse Med. 2019, 48, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, B.; Bolea, R.; Andrés-Lasheras, S.; Sevilla, E.; Samper, S.; Morales, M.; Vargas, A.; Chirino-Trejo, M.; Badiola, J.J. Antimicrobial Susceptibilities and Phylogenetic Analyses of Enterococcus hirae Isolated from Broilers with Valvular Endocarditis. Avian Dis. 2019, 63, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinh, D.C.; Nichol, K.A.; Rand, F.; Embil, J.M. Native-valve bacterial endocarditis caused by Lactococcus garvieae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2006, 56, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Matsuo, T.; Kawai, F.; Uehara, Y.; Mori, N. Enterococcus hirae bacteremia associated with acute pyelonephritis in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis: A case report and literature review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévesque, S.; Dufresne, P.J.; Soualhine, H.; Domingo, M.-C.; Bekal, S.; Lefebvre, B.; Tremblay, C. A Side by Side Comparison of Bruker Biotyper and VITEK MS: Utility of MALDI-TOF MS Technology for Microorganism Identification in a Public Health Reference Laboratory. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.J.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freeman, L.; Milkovits, A.; McDaniel, L.; Everson, N. Evaluation of penicillin-gentamicin and dual beta-lactam therapies in Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 59, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hidalgo, N.; Almirante, B.; Gavaldà, J.; Gurgui, M.; Peña, C.; De Alarcón, A.; Ruiz, J.; Vilacosta, I.; Montejo, M.; Vallejo, N.; et al. Ampicillin plus ceftriaxone is as effective as ampicillin plus gentamicin for treating enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).