Abstract

A major modifiable factor contributing to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is inappropriate use and overuse of antimicrobials, such as antibiotics. This study aimed to describe the content and mechanism of action of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) interventions to improve appropriate antibiotic use for respiratory tract infections (RTI) in primary and community care. This study also aimed to describe who these interventions were aimed at and the specific behaviors targeted for change. Evidence-based guidelines, peer-review publications, and infection experts were consulted to identify behaviors relevant to AMS for RTI in primary care and interventions to target these behaviors. Behavior change tools were used to describe the content of interventions. Theoretical frameworks were used to describe mechanisms of action. A total of 32 behaviors targeting six different groups were identified (patients; prescribers; community pharmacists; providers; commissioners; providers and commissioners). Thirty-nine interventions targeting the behaviors were identified (patients = 15, prescribers = 22, community pharmacy staff = 8, providers = 18, and commissioners = 18). Interventions targeted a mean of 5.8 behaviors (range 1–27). Influences on behavior most frequently targeted by interventions were psychological capability (knowledge and skills); reflective motivation (beliefs about consequences, intentions, social/professional role and identity); and physical opportunity (environmental context and resources). Interventions were most commonly characterized as achieving change by training, enabling, or educating and were delivered mainly through guidelines, service provision, and communications & marketing. Interventions included a mean of four Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) (range 1–14). We identified little intervention content targeting automatic motivation and social opportunity influences on behavior. The majority of interventions focussed on education and training, which target knowledge and skills though the provision of instructions on how to perform a behavior and information about health consequences. Interventions could be refined with the inclusion of relevant BCTs, such as goal-setting and action planning (identified in only a few interventions), to translate instruction on how to perform a behavior into action. This study provides a platform to refine content and plan evaluation of antimicrobial stewardship interventions.

1. Introduction

The number of serious infections resistant to treatment is increasing and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the major risks facing public health [1,2]. In Europe, AMR is associated with approximately 25,000 deaths per year and 700,000 globally [3]. It is estimated that a continued rise in resistance would cost the world 100 trillion USD by 2050 if AMR is not addressed effectively [4]. The Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance report to the WHO recommends countries reduce the need for antimicrobials and enhance their responsible and prudent use, as well as advises the use of behavior change interventions aimed at both public and professionals [5].

One of the major modifiable factors contributing to AMR is inappropriate use and overuse of antimicrobials such as antibiotics [3]. In the UK, 72% of antibiotics are prescribed in General Practice (GP) [6]. Although consumption of antibiotics in UK primary care decreased by 16.7% between 2014–2018 [6], this more than a third higher than some other European countries, such as Sweden and The Netherlands [7].

The first step in intervention design is to specify the behavior(s) the intervention is aimed at changing [8]. Both prescribers’ and patients’ behavior is associated with the inappropriate use and misuse of antibiotics [9]. Prescribers may issue unnecessary prescription of antibiotics to patients with self-limiting infections [10] or inappropriately select the type and duration of the medication [11]. A European Center for Disease Prevention and Control survey of healthcare professionals reported that only 63% agreed or strongly agreed they have a key role in helping control antibiotic resistance [12]. Public misconceptions on the indications and effectiveness of antibiotics are prevalent with only 43% of respondents in a European Commission survey of general public views of antimicrobial resistance knowing that antibiotics are ineffective against viruses [13]. Patient’s expectations around the use of antibiotics can influence the GP’s prescribing behavior and lead to inappropriate prescribing and overuse [14].

The optimization of prescribing practice through antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programs was one of seven key priority areas for action in the UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018 [15]. AMS includes various initiatives to tackle AMR and improve patient safety, for example: establishing optimal standards for antimicrobial use within the healthcare setting, interventions aiming to promote appropriate prescribing, and reviewing the impact of the AMS initiatives. Multifaceted AMS programs aimed at the public, as well as frontline healthcare professionals, are needed to tackle AMR [16,17]. Moreover, there is evidence that the culture of the healthcare organization may also influence the prescribing behavior [18].

A number of policies and interventions have been developed and nationally implemented. However, it is unclear if these interventions focus on the behaviors that would optimally impact on AMR and whether they use the full range of intervention types and policy levers available. It is also unclear if the current program of AMS interventions aim to change behavior through the mechanisms hypothesized to be effective in behavior change theory.

Pinder et al. [19] conducted a review of 150 studies and identified key behaviors that should be targeted in AMS interventions and proposed potential opportunities for new interventions. They also identified a small number of nationally implemented interventions that were mapped to the barriers and facilitators found in the literature. To optimize the potential of AMS programs, the behaviors and populations targeted by these interventions, as well as their content and mechanisms of action of these needs, to be articulated. Tools developed in behavioral science can support such work.

The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) [20] is a synthesis of 19 frameworks of behavior change and can be used to characterize the content of interventions. The BCW is linked to a model of behavior, COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation–Behavior), which can be used to identify the mechanisms of action of interventions. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) can be considered an elaboration of COM-B (see Table S1). McParland [21] used the TDF and the Behavior Change Technique (BCT) Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1) [22], a classification of “active ingredients” that are used to change behavior, to describe public awareness AMR interventions. The authors concluded that there is a clear potential for improvement of interventions. However, the review focused on 20 peer-reviewed studies of interventions aimed at the general public only. There remains a need to review nationally implemented interventions that target both healthcare professionals, as well as the public. To the authors’ knowledge, the BCW has not been used to review AMS interventions already implemented nationally across England to analyze and improve the AMS initiatives.

The overarching aim of this study was to build on the work of Pinder et al. [19] by characterizing nationally implemented AMS primary care programs to identify any gaps in coverage and opportunities for refinement. The specific aims were to:

- identify the behaviors and target populations related to AMS for respiratory tract infection (RTI) in primary care;

- identify interventions targeting AMS for RTI in primary care;

- describe their content using the Behavior Change Wheel and BCT;

- describe their mechanisms of action of interventions using COM-B and TDF.

Research identifying gaps between the influences and behavioral content of AMS interventions to highlight potential avenues for improvement will be reported in a separate study.

2. Methods

We drew on the following sources to identify behaviors relevant to patient self-care and/or appropriate antibiotic advice for the management of signs and symptoms of self-limiting respiratory tract infections:

- A literature review and high level behavioral analysis of antibiotic prescribing in the public, primary and secondary care [19].

- Relevant official guidance [17,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

- UK AMR five-year strategy [15].

- Consultation with experts in epidemiology, pharmacy, infection management, and behavioral science.

- Self-limiting respiratory tract infections and symptoms of respiratory tract infections, included acute cough/acute bronchitis, common colds, flu, acute otitis media, acute otitis externa, (middle) ear infections, acute sinusitis, sore throat (tonsillitis), pharyngitis, laryngitis, bronchitis, respiratory tract infection, tracheitis, and acute rhinitis.

To describe the content of nationally adopted AMS interventions in England, authors identified potentially relevant programs for inclusion based on their knowledge of the policy area, consultation with key stakeholders and review of relevant documentation.

We included interventions implemented nationally in England between January 2014 and February 2018, where the primary objective was antimicrobial stewardship activities related to patient self-care and/or appropriate antibiotic advice for the management of respiratory tract infections. Interventions were excluded if local implementation only had occurred. Two authors (AS and VdLM) sought descriptions of the interventions from publicly available material and in some instances contacted the program leads for elaboration and to ensure accurate descriptions.

Providers and commissioners were defined as follows: providers defined as professionals in organizations providing care for the management of signs and symptoms of RTIs, e.g., Trusts, General Practice, private providers, and commissioners defined as professionals in organizations commissioning services for the management of signs and symptoms of self-limiting RTIs, e.g., Local Authorities, Clinical Commissioning Groups, Clinical Services Units, and National Health Service England.

Data Extraction Tools

The BCW and BCTTv1 were used to classify intervention content identified in intervention materials or descriptions of interventions into intervention types, policy options (see Table S2), and BCTs.

To describe the intervention mechanisms of action, we were guided by three matrices—two linking BCTs to TDF domains [33,34] and one linking intervention types to COM-B and TDF [8] to determine from the BCTs we identified in interventions, which influences on behavior (characterized using COM-B and TDF) the BCTs were likely to be targeting.

3. Data Analysis

For each intervention, we recorded the total number of COM-B components and TDF domains, intervention types, policy options, and BCTs, and calculated the mean and range. We recorded the number of interventions in which each COM-B component, TDF domain, intervention types, BCT, and policy option was present (mean and range).

Interrater Reliability

One researcher (LA) conducted 100% of the coding, and a second researcher (AS) coded 20% to establish reliability. Percentage agreement for each section of intervention coded was calculated where both coders assigned the same code(s) to the same section of intervention material. PABAK (Prevalence And Bias-Adjusted Kappa) statistic [35] was used to assess the presence or absence of codes within each intervention. This statistic adjusts for shared bias in the coders’ use of options and high prevalence of negative agreement, i.e., when both coders agree that codes are not present. Interrater reliability of 0.60–0.79 = ‘substantial’ reliability, >0.80 = ‘outstanding’ [36].

4. Results

We identified 32 behaviors related to AMS for RTI in primary care. These are summarized in Table 1 (see Table S3 for the sources from which behaviors were identified). Five were patient behaviors, 11 related to prescribers, five were community pharmacist behaviors, two related to providers, one related to commissioners), and eight related to both providers and commissioners.

Table 1.

Behaviors related to antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections (RTI) in primary care.

A total of 83 interventions were identified for content analysis of nationally adopted AMS interventions in England. Thirty-nine met the inclusion criteria (Table 2 with the target group(s)). Of the 44 excluded interventions: 31 were not aimed at the relevant behaviors or target groups; five were information, general media, or links to resources only; four were not nationally implemented; and four were part of other already identified interventions.

Table 2.

Intervention and target group.

Of the 39 included interventions, 15 were aimed at patients/public, 22 at prescribers, eight at community pharmacy staff, 18 at providers, and 18 at commissioners. Almost half of the interventions (n = 19) were aimed at one target group only, nine were aimed at two target groups and three interventions (Public Health England’s Antibiotic Guardian [37], TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) [38], and British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy’s Antibiotic Action [39]) were aimed at all five target groups. A mean of 5.8 behaviors were targeted by interventions.

Patient interventions were largely aimed at encouraging self-care and reducing requests for antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections (e.g., Antibiotic Guardian, Treat Yourself Better [40]). Interventions aimed at prescribers targeted various behaviors, but most commonly the behavior that antibiotic prescriptions ‘should be written only when there is a clear clinical benefit’ (e.g., UK Department of Health and Public Health England’s Antimicrobial Prescribing and Stewardship Competencies [41]), followed by the behavior to ‘provide a backup prescription where appropriate’ (e.g., TARGET). The behavior targeted least was that prescribing antibiotics following a telephone consultation should only occur in exceptional circumstances (e.g., NICE Infection Prevention and Control (QS61) [27]). Interventions targeting pharmacies were largely aimed at provision of self-care advice (e.g., NICE Antimicrobial stewardship: changing risk-related behaviors in the general population NICE guideline (NG63) [23]) and sharing written resources with the patient (e.g., The Learning Pharmacy [42]). The most frequently targeted behavior for providers and commissioners was ‘monitor antibiotic prescribing in relation to local and national resistance patterns or targets’ (e.g., TARGET).

4.1. Interrater Reliability

The kappa ranged from 0.60 to 0.89 suggesting good to very good inter-rater reliability. The PABAK was from 0.75 to 0.95, suggesting substantial to outstanding agreement. Kappa and PABAK for behaviors, mechanism of action (COM-B, TDF), and intervention content (intervention types, policy options, BCTs) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Interrater reliability.

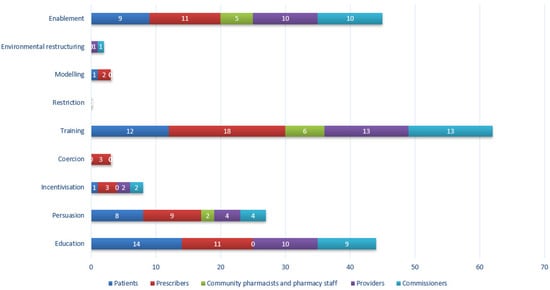

4.2. Intervention Types Identified in Interventions

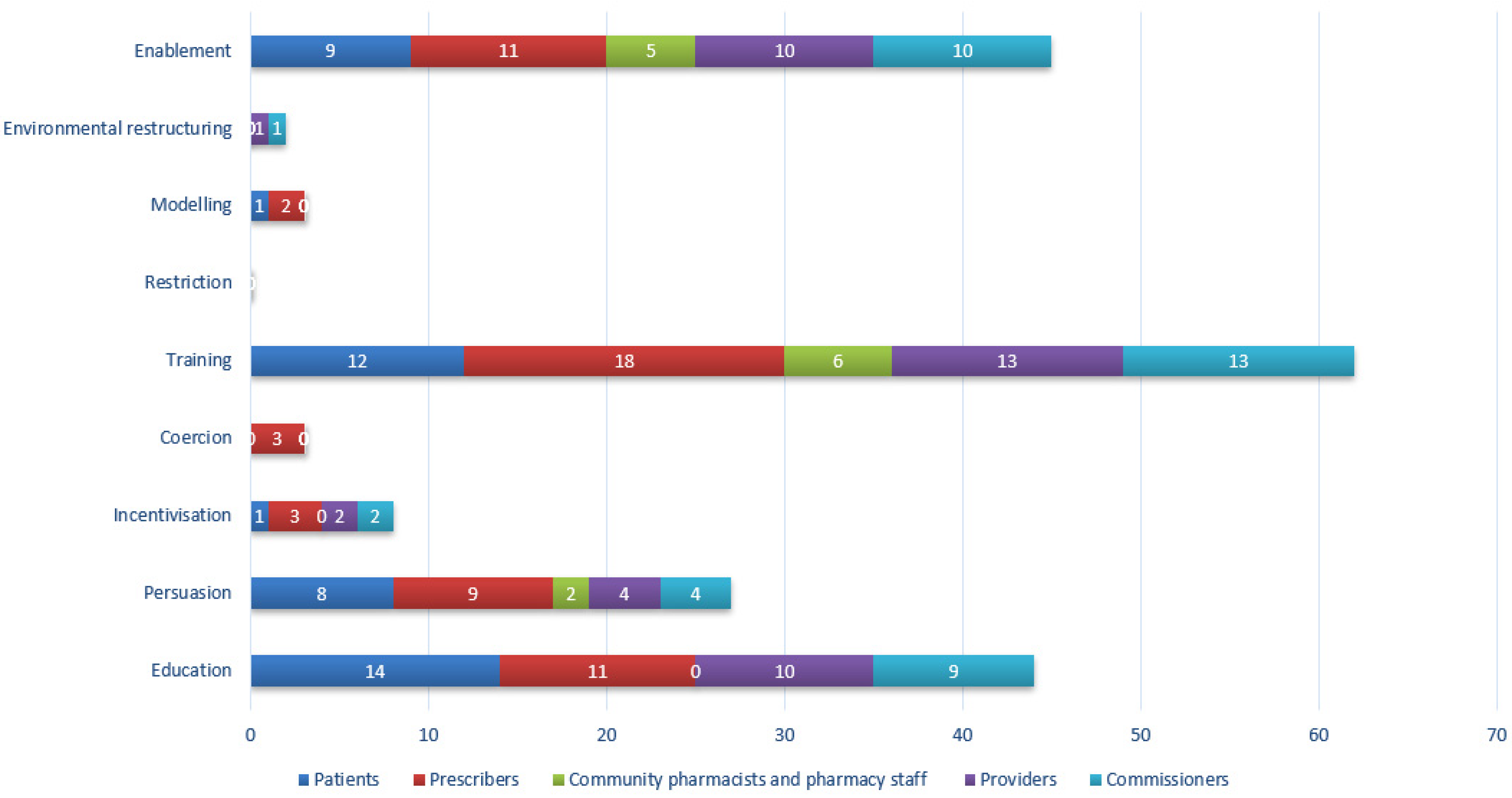

Eight of a potential nine intervention types were identified across all interventions (Table 4). The mean number of intervention types per intervention was 3 (range 1–6). Figure 1 shows the number of types identified in interventions split by target group. Patient interventions often used education, training and persuasion. Prescriber interventions included seven out of nine intervention types, primarily training, education, and persuasion. Pharmacy interventions frequently used enablement and training but also used education and persuasion covering four of the nine possible intervention types. Provider and commissioner interventions were most frequently training, enablement, and education. No interventions used restriction.

Table 4.

Frequency of types in interventions.

Figure 1.

Frequency of identification of intervention types by target group. Total count will exceed the maximum number of interventions (n = 39) as many interventions were aimed at more than one target group.

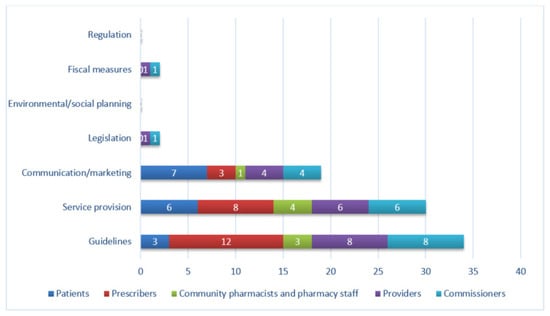

4.3. Policy Options Identified in Interventions

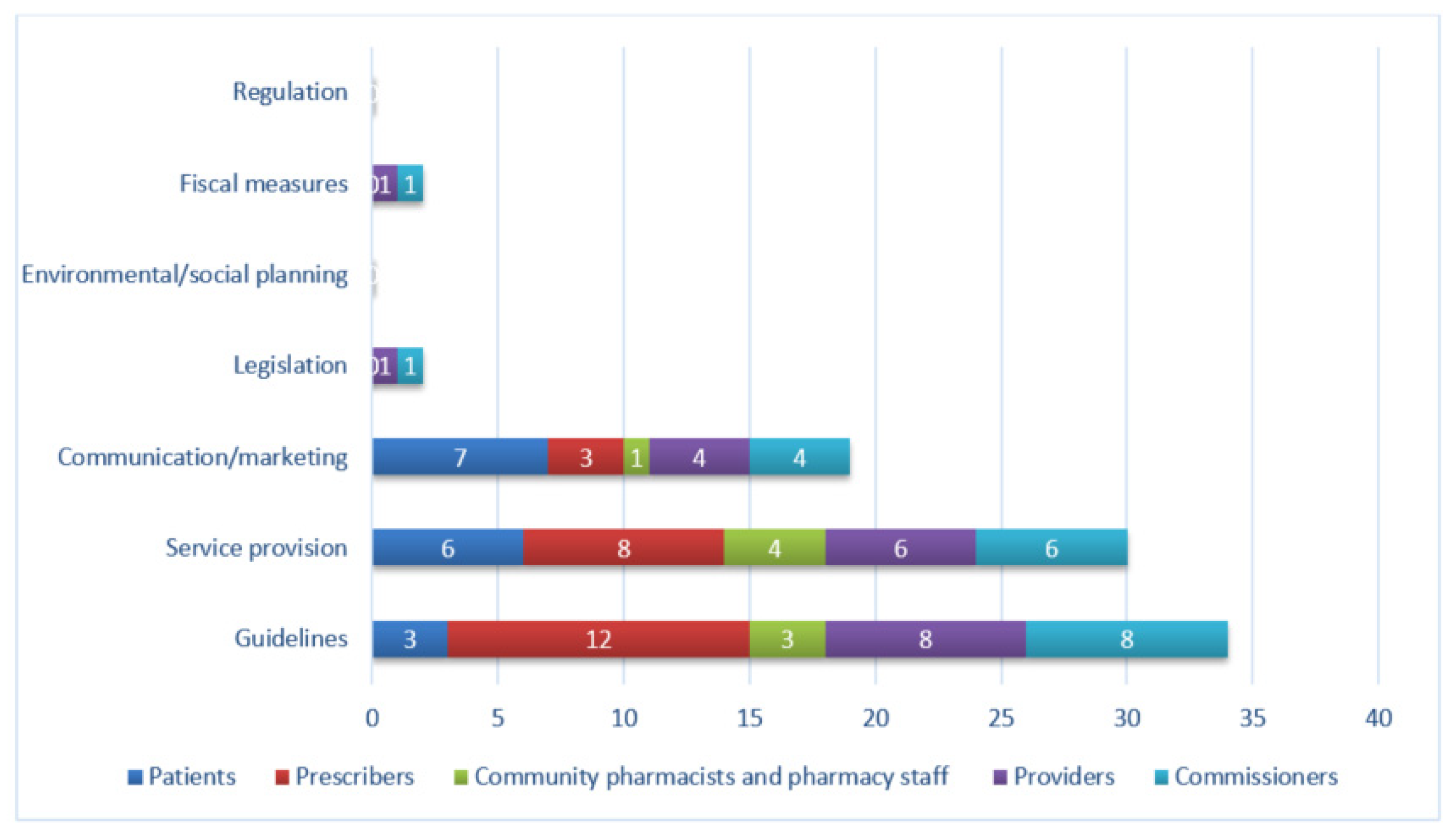

Five policy options were identified across the 39 interventions. ‘Service provision,’ e.g., website, was the most frequently identified (15/39), followed by ‘guidelines,’ e.g., NICE guidance, (14/39), ‘communication / marketing,’ e.g., poster, (10/39), ‘legislation,’ i.e., Health and Social Care Act (1/39), and ‘fiscal measures’, i.e., NHS Quality Premiums for CCGs (1/39). Figure 2 shows the number of policy options identified in interventions split by target group. No interventions were delivered through environmental/social planning or regulation. Patient interventions were commonly delivered using communication/marketing and service provision, while prescriber interventions were delivered mainly through guidelines, followed by service provision. Provider and commissioner interventions were delivered largely through guidelines and service provision, with some communication/marketing and legislation.

Figure 2.

Frequency of identification of policy options, by target group. Total count will exceed the maximum number of interventions (n = 39) as many interventions were aimed at more than one target group.

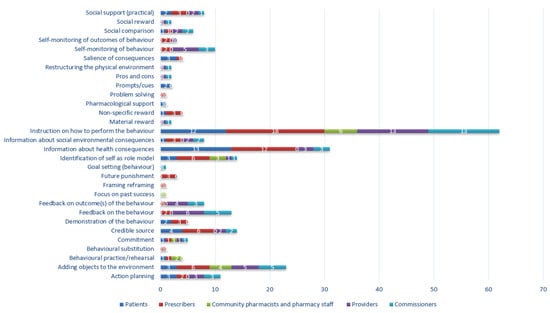

4.4. BCTs Identified in Interventions

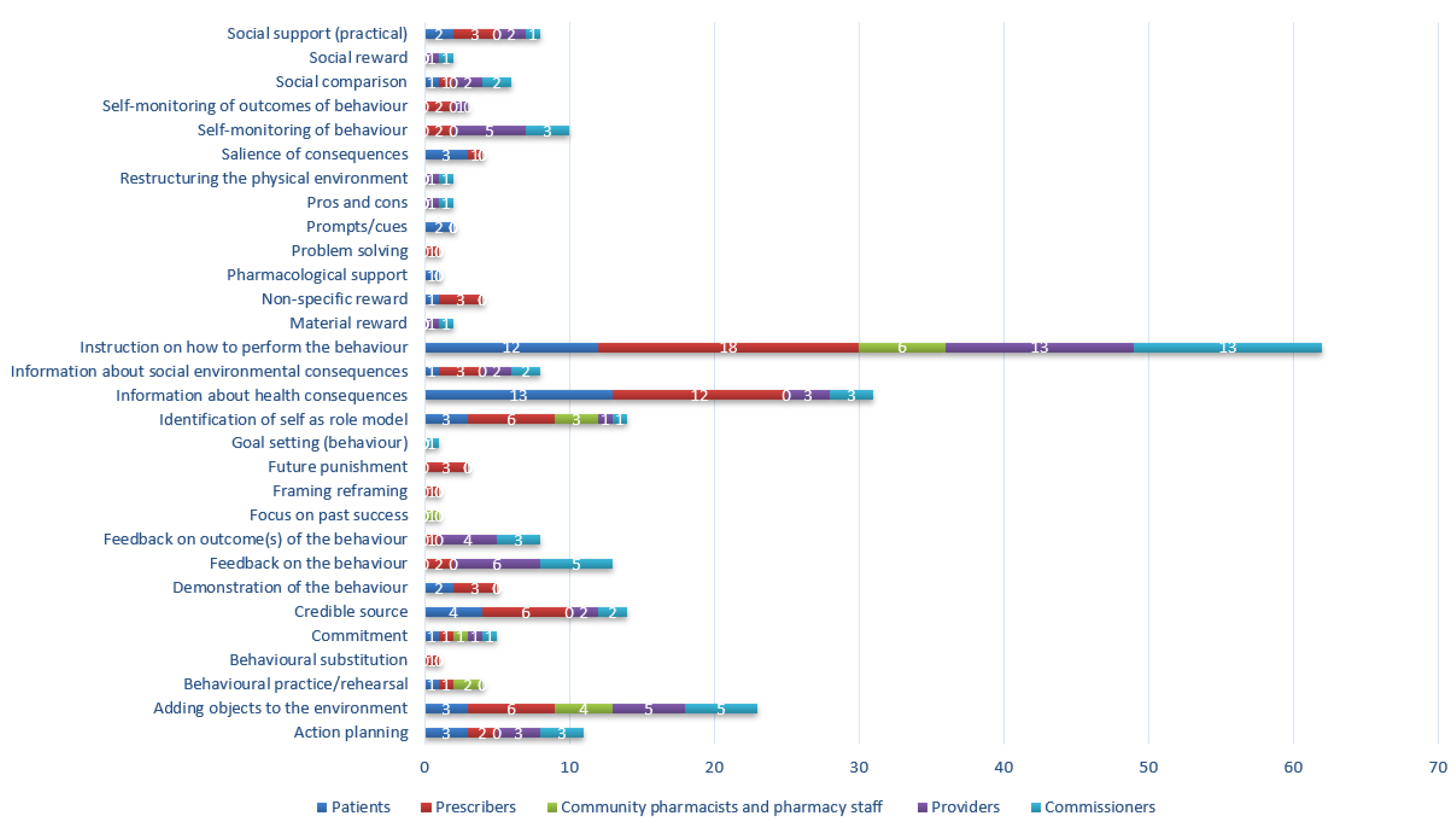

A total of 30 BCTs were identified across all interventions with the mean number of 4 per intervention (range 1–14) as shown in Table 5. Figure 3 shows the number of BCTs identified in interventions split by target group. Patient and prescriber interventions most commonly used the BCTs ‘information about health consequences’ and ‘instruction on how to perform the behavior’. The most frequently used BCT in pharmacy, provider, and commissioner interventions was ‘instruction on how to perform the behavior.’

Table 5.

Frequency of Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) in interventions.

Figure 3.

Frequency of identification of BCTs, by target group.

The frequency of mechanisms of action identified in interventions is outlined in Table 6.

Table 6.

Frequency of interventions targeting influences on behavior.

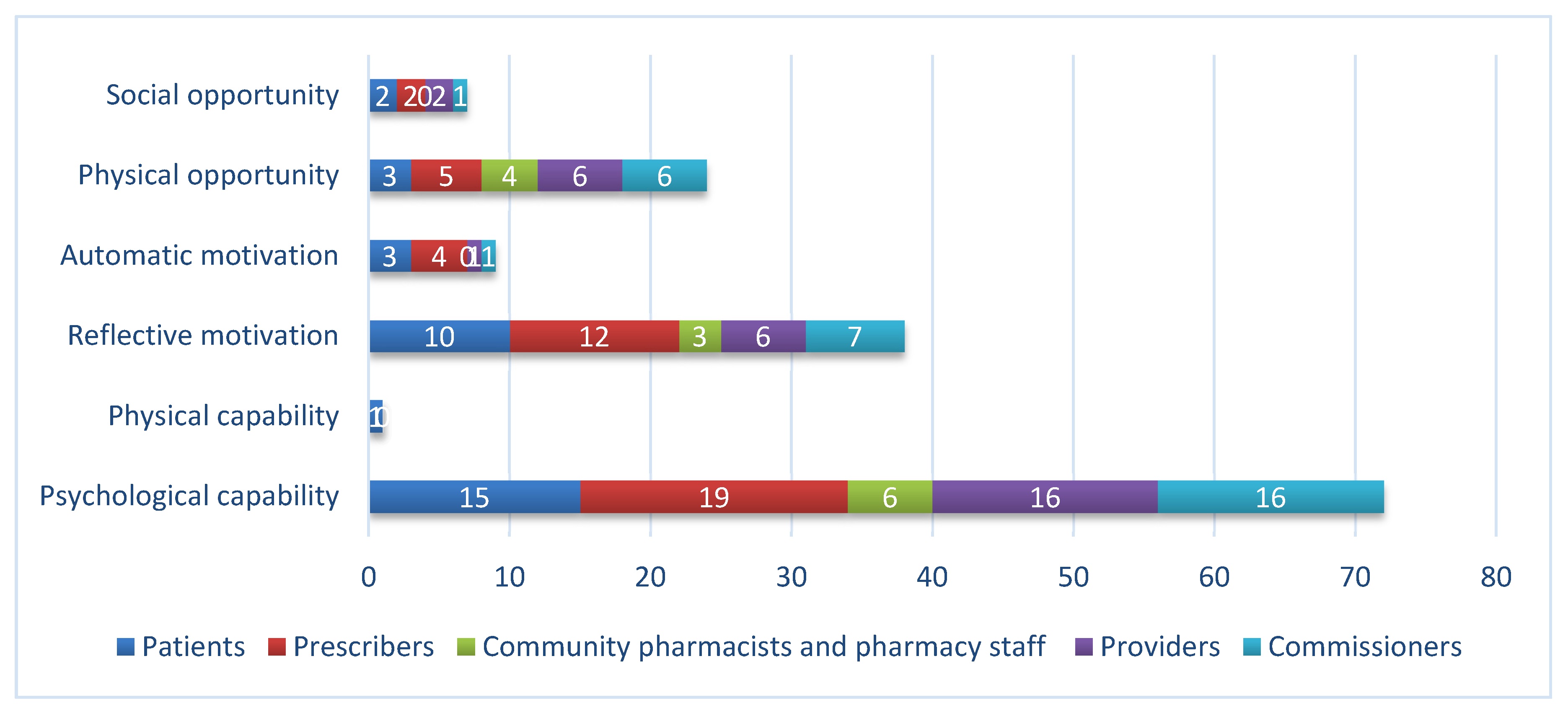

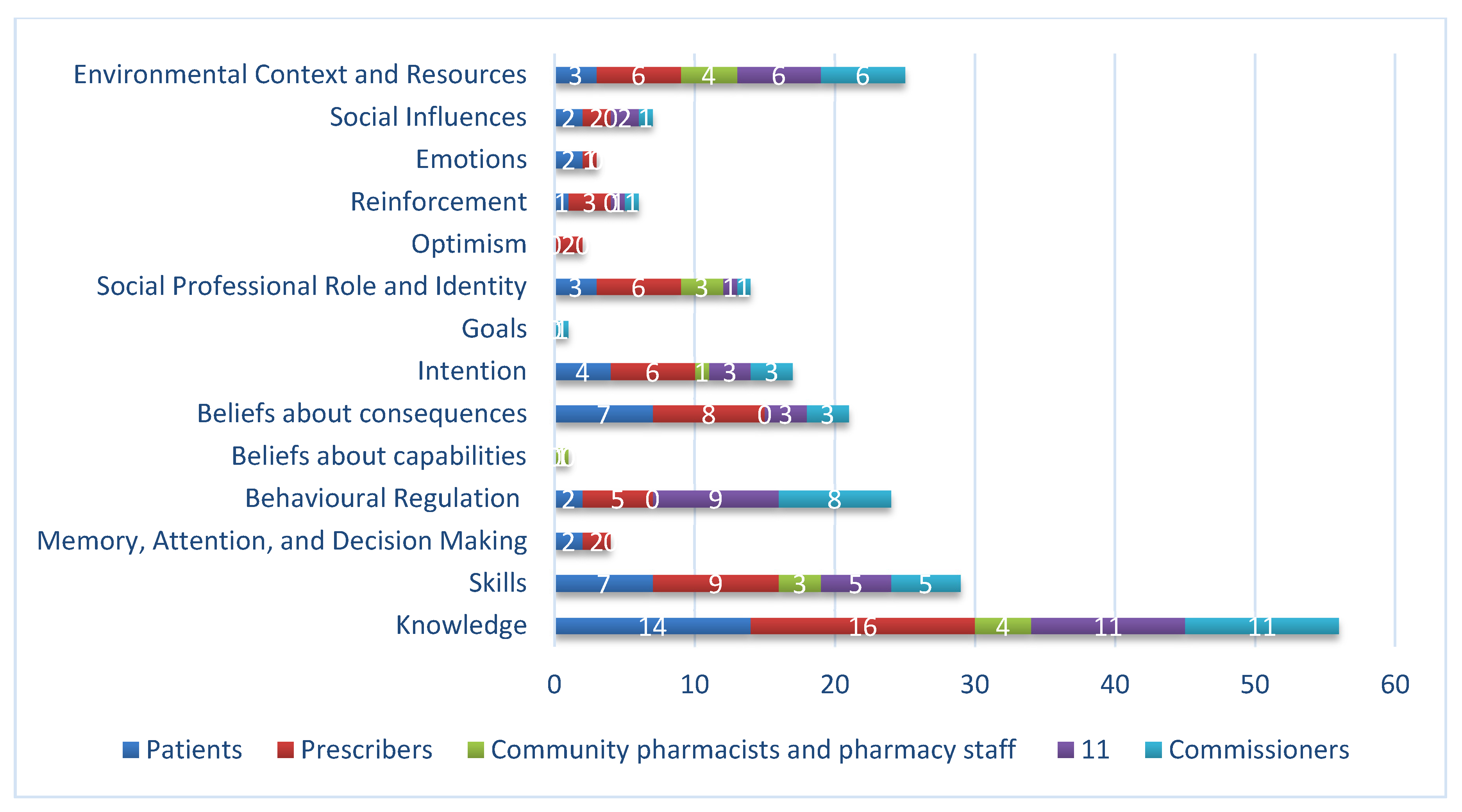

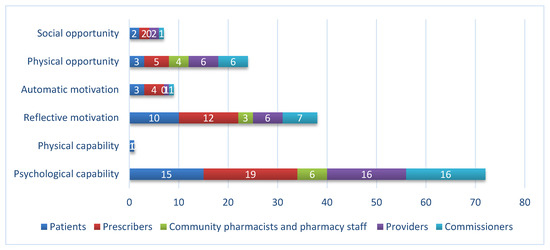

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the influences on behavior targeted in interventions split by target groups. The most frequently targeted influence on behavior was psychological capability for all target groups. For patients, prescribers and commissioners reflective motivation was the next most frequently targeted influence on behavior, whilst for pharmacy and provider interventions, it was physical opportunity. Automatic motivation and social opportunity were infrequently targeted. Only one intervention aimed to change physical capability.

Figure 4.

Influences (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation–Behavior (COM-B)) on behavior targeted in interventions, by target group.

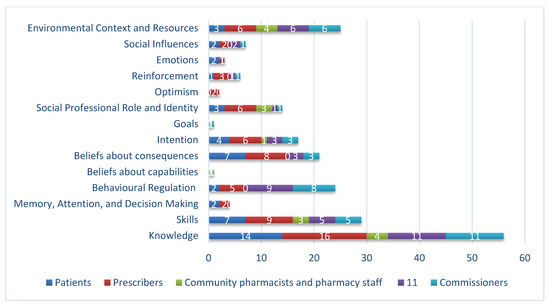

Figure 5.

Influences (Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)) on behavior targeted in interventions, by target group.

The TDF domain, knowledge, was the most frequently targeted influence for all target groups; for pharmacy interventions, ‘environmental context and resources’ was equally prevalent. For patients and prescribers, the next most commonly targeted influences were beliefs about consequences and skills. For pharmacy it was social and professional role and identity and skills. Interventions for providers and commissioners also targeted behavioral regulation and environmental context and resources.

5. Discussion

The overall aim of current research was to gain a detailed understanding of existing AMS national interventions, to pinpoint key areas of focus, and potential gaps and opportunities for future interventions. This study identified behaviors and target populations related to AMS for RTI in primary care and characterized the content and mechanism of action of interventions of nationally implemented AMS interventions targeted in primary care (patients and public, prescribers, providers, commissioners, and pharmacy).

Of the 32 behaviors identified, approximately one-third were related to prescribers, one third related both to providers and commissioners, and the remaining third was evenly split between patients and community pharmacy staff. The focus of interventions for patients was on self-care and not requesting antibiotics at consultations. The majority of prescriber interventions encouraged ‘prescribing only when there is a clear clinical benefit’, ‘giving alternative self-care advice’, ‘providing a back-up prescription where appropriate’, and ‘following local antibiotic formularies.’ Few interventions addressed limiting prescribing following telephone consultation and undertaking point of care tests (POCT), such as CRP. Given the potential for POCT to reduce inappropriate prescribing [67] related behaviors should be considered in the design or refinement of future interventions. Pharmacy interventions were aimed at provision of self-care advice, sharing written resources and checking antibiotic prescriptions comply with local guidance and querying those that do not. Provider and commissioner interventions focused on ‘monitoring prescribing in relation to local and national resistance patterns’, and ‘commissioning, developing, and implementing interventions to support AMS’.

We identified 39 national AMS interventions for RTI in primary care. Interventions were typically in the form of ‘service provision’, such as a website or clinical guidelines followed by communications/marketing. Approximately three-quarters of the interventions were ‘training’ mainly using the BCT, ‘instruction on how to perform the behavior’ and includes training programs, such as TARGET [38], Stemming the Tide of Antibiotic Resistance (STAR) e-learning [44], Managing Acute Respiratory Tract Infections (MARTI) e-learning [45], and Public Health England’s ‘Beat the Bugs’ course [46]. The same proportion served were classed as ‘education’ mostly frequently using the BCT ‘information about health consequences.’ Twenty-five interventions were classed as ‘enabling,’ delivered most frequently with the BCT ’adding objects to the environment,’ such as the provision of a checklist to prevent antimicrobial misuse. Eighteen interventions used ‘persuasion’ mostly through the BCT ‘credible source,’ for example, providing an experienced GP’s view of implementing delayed prescriptions. Few to no interventions used restriction, environmental restructuring, modeling and coercion.

The most frequently identified mechanisms of action, by which interventions aimed to change behavior, were ‘psychological capability’ (‘knowledge’, ‘skills’ and ‘behavioral regulation’); ‘reflective motivation’ (‘beliefs about consequences’ and ‘intention’) and ‘physical opportunity’ (‘environmental context and resources, e.g., sharing leaflets with patients); the latter particularly so for community pharmacy interventions. These findings suggest that intervention designers believe that increasing knowledge and motivation among all target groups is key to decreasing inappropriate antibiotic consumption.

Psychological capability was targeted in all groups, delivered largely through ‘instruction on how to perform the behavior. Reflective motivation and psychological capability were targeted in patients and prescribers using the BCT ‘information about health consequences’. Interventions targeting patients and prescribers through ‘beliefs about consequences’ (e.g., NHS England’s Patient Safety Alert [47], Public Health England’s Keep Antibiotics Working campaign [48]) could have drawn on a much wider range of techniques. For example, BCT ‘information about emotional consequences’ (e.g., the anxiety of becoming ill knowing antibiotics would not be effective), or BCT ‘anticipated regret’ (e.g., the degree of regret prescribers may feel in the future if they do not modify their antibiotic prescribing), or by employing incentives or rewards. Provider and commissioner interventions focused more on ‘Feedback on behavior’, for example interventions giving feedback on prescribing and local antimicrobial resistance rates (e.g., NHS England Quality Premium: 2016/17 Guidance for CCGs [49], Public Health England Fingertips platform [50] and PrescQIPP Antimicrobial Stewardship [51]) with the aim of facilitating a change in behavioral regulation (the mental skills to carry out the mental tasks required to perform the behavior).

Physical opportunity was another commonly targeted domain in interventions aimed at all target groups. The most frequently used technique was ‘adding objects to the environment’ (i.e., provision of information leaflets). Many other techniques appropriate for targeting this domain were not used, for example, avoiding/reducing exposure to cues for the behavior which could, e.g., involve diverting patients with self-limiting infections to the pharmacy via appointment booking lines as suggested in Pinder et al. [19].

With the exception of community pharmacy, Interventions were identified across all settings, which targeted social opportunity through social comparison with peers (e.g., UK Chief Medical Officer letter to high prescribers of antibiotics [52]) and practical social support (e.g., Self Care Forum: Self Care Week [53]).

We identified few (8/39) interventions which aimed to change behavior by targeting ‘automatic motivation’, such as routines and habits (e.g., encouraging routine feedback where antibiotics are not prescribed according to guidelines), emotional drives (e.g., addressing concerns about the negative consequences of not prescribing antibiotics), and reinforcement (e.g., incentivizing participation in AMS training), which can be powerful influences on behavior. Designing new interventions and refining existing interventions may merit considering targeting these influences.

6. Limitations

There are three key limitations to this study. First, the interventions included in this study are implemented at a national level. The devolution of responsibility to local health and public health teams means the many interventions which were designed and implemented locally are not included. Secondly, we did not establish the extent to which included interventions were effective in changing behavior nor the extent to which they are implemented. Thirdly, whilst we obtained most of the materials and documents related to each included intervention, we were unable to access all materials.

7. Future Research Directions

The mechanisms of action of interventions were determined by applying available resources which link COM-B and TDF to intervention content (intervention types and BCTs). This process established how interventions are likely to have an effect on behavior. Future intervention design and refinement would be supported by establishing the barriers and facilitators to the behaviors identified in this study and then comparing them with intervention content to determine the extent to which intervention content appropriately targets identified barriers and facilitators. Establishing the extent to which interventions are effective will support interpretation of these findings. Establishing which behaviors are key in influencing AMR will support the prioritization of intervention design and refinement.

Intervention design and refinement would be aided with the provision of accessible guidance on processes such as that described above to support intervention designers with a range of expertise in behavior change.

8. Conclusions

Although changing behaviors alone cannot fully halt the AMR problem, patient and physician behaviors in primary care offer a unique opportunity for AMR interventions. Targeting behaviors amenable to change using effective, evidence-based BCTs, may offer new cost-effective methods to reduce antibiotic prescribing and thus halt the rise in the number of patients suffering from infections due to AMR. This study highlights the need to review existing interventions to ensure they are optimized to influence AMR-related behaviors. Any gaps identified in current provision should be considered for future intervention design and refinement, ensuring these are aligned to work within the NHS’s changing provision of primary care.

9. Declarations

9.1. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

9.2. Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

9.3. Availability of Data and Material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/9/8/512/s1, Table S1: Labels, definitions and examples of COM-B and Theoretical Domains Framework; Table S2: Behaviour Change Wheel labels, definitions and examples; Table S3: Source materials for behavior; Table S4: Summary of intervention content, mechanism of action and target behaviour.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and A.S.; formal analysis, L.A. and A.S.; investigation, L.A., P.B., N.H., V.d.L.M., M.G.-I. and A.S.; methodology, L.A., T.C. and A.S.; supervision, T.C.; writing—original draft, L.A. and A.S.; writing—review & editing, T.C., P.B., D.A.-O., E.B., N.H., V.d.L.M, M.G.-I., S.H. and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by Public Health England.

Conflicts of Interest

T.C., P.B., D.A.-O., S.H. and A.S. are employed by project funders, Public Health England.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of intervention, target group, behavior, mechanism of action, and intervention content.

Table A1.

Summary of intervention, target group, behavior, mechanism of action, and intervention content.

| Mechanism of Action | Intervention Content | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Target Group | Behavior | COM-B | TDF | Intervention Type | BCT | Policy Option |

| Public Health England Antibiotic Guardian [37] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Commitment | Service provision |

| Prescribers |

| Reflective motivation | Social influences | Persuasion | Adding objects to the environment | Communication and marketing | |

| Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Automatic motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Training | Credible source | ||

| Providers |

| Physical opportunity | Intention | Incentivization | Social reward | ||

| Commissioners |

| Social opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Enablement | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||

| Memory attention and decision making | Modeling | Prompts/cues | ||||

| Emotion | Information about health consequences | |||||

| Social professional role and identity | Salience of consequences | |||||

| Demonstration of the behavior | ||||||

| Identification of self as role model | ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| UK Department of Health and Public Health England Antimicrobial Prescribing and Stewardship Competencies [41] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | Guidelines |

| Providers |

| Behavioral regulation | Training | Self-monitoring of outcomes of behavior | |||

| Commissioners |

| Social support (practical) | |||||

| Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| The Health and Social Care Act (HSCA) 2008. Code of Practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance [54] | Providers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Regulation |

| Commissioners |

| ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NICE Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use [NG15] [17] | Providers |

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Commissioners |

| Behavioral regulation | Education | Self-monitoring of outcomes of behavior | |||

| Prescribers |

| ||||||

| Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NICE Infection Prevention and Control [QS61] [27] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Prescribers |

| Skills | Training | Self-monitoring of the behavior | |||

| Providers |

| Behavioral regulation | Enablement | Action planning | |||

| Commissioners |

| Information about health consequences | |||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NHS England Quality Premium: 2016/17 Guidance for CCGs [49] | Providers |

| Automatic motivation | Reinforcement | Incentivization | Material reward | Fiscal measures |

| Commissioners |

| Psychological capability | Behavioral regulation | Education | Feedback on the behavior | ||

| NHS England Patient Safety Alert—addressing antimicrobial resistance through implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program [47] | Providers |

| Physical opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | Communication/marketing |

| Commissioners | Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Education | Information about health consequences | |||

| TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) [38] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Behavioral regulation | Education | Action planning | Service provision |

| Prescribers |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | Guidelines | |

| Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Automatic motivation | Skills | Incentivization | Demonstration of the behavior | Communication and marketing | |

| Providers |

| Physical opportunity | Knowledge | Modeling | Feedback on the behavior | ||

| Commissioners |

| Social opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Persuasion | Identification of self as role model | ||

| Intention | Training | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Reinforcement | Information about social environmental consequences | |||||

| Social influences | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||||

| Social professional role and identity | Reward (non material) | |||||

| Self-monitoring of the behavior | ||||||

| Credible source | ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Treat Yourself Better [40] | Patients |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Persuasion | Credible source | Communication and marketing |

| Social opportunity | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||||

| Social influences | Enablement | Social comparison | |||||

| Beliefs about consequences | Information about social and environmental consequences | ||||||

| UK Chief Medical Officer letter to high prescribers of antibiotics [52] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Behavioral regulation | Persuasion | Social comparison | Communication/marketing |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Training | Credible source | |||

| Physical opportunity | Knowledge | Education | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||

| Environmental context and resources | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | ||||

| Beliefs about consequences | Behavioral substitution | ||||||

| Optimism | Feedback on the behavior | ||||||

| Information about health consequences | |||||||

| Public Health England Fingertips platform [50] | Commissioners |

| Psychological capability | Behavioral regulation | Education | Feedback on the behavior | Service provision |

| Providers |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Enablement | Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior | ||

| Knowledge | Social comparison | ||||||

| Information about health consequences | |||||||

| PrescQIPP Antimicrobial Stewardship [51] | Prescribers |

| Physical opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Enablement | Social support (practical) | Service provision |

| Providers |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Education | Information about social and environmental consequences | ||

| Commissioners |

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||

| Social opportunity | Behavioral regulation | Persuasion | Pros and cons | ||||

| Social influences | Feedback on the behavior | ||||||

| Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior | |||||||

| Social comparison | |||||||

| UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018 [15] | Prescribers |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Education | Information about health consequences | Guidelines |

| Providers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||

| Commissioners |

| Physical opportunity | Behavioral regulation | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | ||

| Environmental context and resources | Coercion | Future punishment | ||||

| Optimism | Persuasion | Identification of self as role model | ||||

| Social professional role and identity | ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NHS website advice on common cold [55] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Information about health consequences | Service provision |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Education | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||

| Persuasion | Credible source | ||||||

| NICE Antimicrobial stewardship: changing risk-related behaviors in the general population [NG63] [23] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Social opportunity | Social influences | Training | Social support practical | ||

| Providers |

| Behavioral regulation | Enablement | Self-monitoring of behavior | |||

| Commissioners |

| Action planning | |||||

| Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior | ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Center for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education distance course: Antibacterial resistance—a global threat to public health: the role of the pharmacy team [56] | Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Prescribers |

| Behavioral practice/ rehearsal | |||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| UK Clinical Pharmacy Association/Royal Pharmaceutical Society—professional practice curriculum [57] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| FeverPAIN [58] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | Service provision |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Education | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Public health England Managing Common Infections Guidance [28] | Prescribers |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Knowledge | Persuasion | Credible source | ||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NICE Respiratory tract infections (self-limiting): prescribing antibiotics [CG69] [59] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Prescribers |

| Skills | Enablement | Social support practical | |||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NICE Antimicrobial Stewardship [QS121] [29] | Prescribers |

| Physical opportunity | Behavioral regulation | Education | Feedback on behavior | Guidelines |

| Providers |

| Psychological capability | Beliefs about consequences | Enablement | Self-monitoring of behavior | ||

| Commissioners |

| Reflective motivation | Environmental context and resources | Training | Goal setting (behavior) | ||

| Goals | Environmental restructuring | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Knowledge | Persuasion | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||||

| Restructuring the physical environment | ||||||

| Action planning | ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Self Care Forum: Factsheet 7 (Cough in Adults); Factsheet 12 (Common Cold) [60] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Service provision |

| Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Managing Acute Respiratory Tract Infections (MARTI) e-learning [45] | Prescribers |

| Automatic motivation | Reinforcement | Coercion | Action planning | |

| Reflective motivation | Knowledge | Education | Credible source | |||

| Physical opportunity | Social professional role and identity | Enablement | Demonstration of the behavior | |||

| Psychological capability | Beliefs about consequences | Incentivization | Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior | |||

| Skills | Persuasion | Framing/reframing | ||||

| Environmental context and resources | Training | Future punishment | ||||

| Identification of self as role model | ||||||

| Information about health consequences | ||||||

| Information about social environmental consequences | |||||||

| Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||||||

| Non-specific reward | |||||||

| Problem solving | |||||||

| Salience of consequences | |||||||

| Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of the behavior | |||||||

| Stemming the Tide of Antibiotic Resistance (STAR) e-learning [44] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Demonstration of the behavior | Service provision |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Persuasion | Credible source | |||

| Social opportunity | Beliefs about consequences | Modeling | Information about health consequences | |||

| Automatic motivation | Social influences | Incentivization | Behavioral practice/rehearsal | ||||

| Reinforcement | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||||||

| Information about social and environmental consequences | |||||||

| Non-specific reward | |||||||

| OpenPrescribing.net [61] | Providers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Feedback on the behavior | Service provision |

| Commissioners | Enablement | Feedback on the outcome of behavior | |||||

| Adding objects to the environment | |||||||

| CENTOR [62] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Service provision |

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Health Education England ‘Antimicrobial Resistance: A Guide for GPs’ [63] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | Communication and marketing |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Enablement | Social support (practical) | |||

| Automatic motivation | Emotion | Persuasion | Credible source | |||

| Environmental context and resources | Training | Adding objects to the environment | ||||

| Skills | Coercion | Future punishment | ||||

| Social professional role and identity | Identification of self as role model | ||||||

| Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||||||

| Public Health England Keep Antibiotics Working campaign [48] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Credible source | Communication and marketing |

| Providers |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Training | Information about health consequences | ||

| Commissioners |

| Automatic motivation | Emotion | Enablement | Information about social and environmental consequences | ||

| Physical opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Persuasion | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||||

| Intention | Social support (practical) | ||||||

| NICE Sinusitis (acute): antimicrobial prescribing [NG79] [24] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Prescribers |

| Physical capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | ||

| Reflective motivation | Memory attention and decision making | Enablement | Action planning | |||

| Beliefs about consequences | Pharmacological support | |||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| NICE Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing [NG84] [26] | Prescribers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Memory attention and decision making | Education | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Enablement | Action planning | |||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Department of Health & Social Care ‘Take Care not Antibiotics’ videos [64] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Communication and marketing |

| Skills | Education | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Enablement | Action planning | ||||||

| Patient.info webpages on colds, sore throats, antibiotics, bronchitis and sinusitis [65] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | Service provision |

| Reflective motivation | Intention | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||

| |||||||

| Persuasion | Credible source | |||||

| Health Education England ‘Awareness of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Animation’ [66] | Patients |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Persuasion | Salience of consequences | Communication and marketing |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | ||||

| Identification of self as role model | |||||||

| Self Care Forum: Self Care Week [53] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | Communication and marketing |

| Providers |

| Skills | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||

| Commissioners |

| Memory attention and decision making | Enablement | Social support (practical) | |||

| Prompts/cues | |||||||

| theLearningpharmacy.com [42] | Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Service provision |

| Physical opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | |||

| Skills | Behavioral practice/ rehearsal | |||||

| Public Health England ‘Beat the Bugs’ course [46] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Salience of consequences | Service provision |

| Reflective motivation | Behavioral regulation | Enablement | Information about health consequences | |||

| Automatic motivation | Beliefs about consequences | Training | Action-planning | |||

| Reinforcement | Incentivization | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | ||||

| Skills | Persuasion | Behavioral practice/ rehearsal | |||||

| Non-specific reward | |||||||

| Royal Pharmaceutical Society: Antimicrobial Stewardship Quick Reference Guide [31] | Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Reflective motivation | Social professional role and identity | Persuasion | Identification of self as role model | Service provision |

| Psychological capability | Beliefs about capabilities | Training | Focus on past success | |||

| Physical opportunity | Knowledge | Enablement | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | |||

| Environmental context and resources | Adding objects to the environment | ||||||

| Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and Infection Prevention Society (IPS) Infection Prevention and Control Commissioning Toolkit [43] | Providers |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Training | Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Guidelines |

| Commissioners |

| ||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy: Antibiotic Action [39] | Patients |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge | Education | Information about health consequences | Service provision |

| Prescribers |

| Reflective motivation | Social professional role and identity | Persuasion | Identification of self as role model | ||

| Community pharmacists and pharmacy staff |

| Physical opportunity | Environmental context and resources | Enablement | Adding objects to the environment | ||

| Providers |

| ||||||

| Commissioners |

| ||||||

| |||||||

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control European Medicines Agency. The Bacterial Challenge: Time to React; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009.

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/amr/sites/amr/files/amr_action_plan_2017_en.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- HM Goverment and Wellcome Trust. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. 2014. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Ad hoc Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance. No Time to Wait: Securing the Future From Drug-Resistant Infections, in Report to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/interagency-coordination-group/final-report/en/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Public Health England. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2018–2019. Public Health England: London. 2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/843129/English_Surveillance_Programme_for_Antimicrobial_Utilisation_and_Resistance_2019.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Consumption in the EU/EEAAnnual Epidemiological Report for 2018. Stockholm. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Antimicrobial-consumption-EU-EEA.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel—A Guide to Designing Interventions; Silverback Publishing: Great Britain, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin-Crine, S.; Walker, A.S.; Butler, C.C. Contribution of behavioural science to antibiotic stewardship. BMJ 2015, 350, h3413. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26111947 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HM Government & Wellcome Trust. Infection Prevention, Control And Surveillance: Limiting the Development and Spread of Drug Resistance. 2016. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/Health%20infrastructure%20and%20surveillance%20final%20version_LR_NO%20CROPS.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Health Service. The Antibiotic Awareness Campaign. 2015. Available online: http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/ARC/Pages/AboutARC.aspx (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Survey of Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours on Antibiotics, Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance in the EU/EEA. 2019: Stockholm. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/survey-of-healthcare-workers-knowledge-attitudes-behaviours-on-antibiotics.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 478 Report Antimicrobial Resistance. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/surveyKy/2190 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Cals, J.W.; Boumans, D.; Lardinois, R.J.; Gonzales, R.; Hopstaken, R.M.; Butler, C.C.; Dinant, G.J. Public beliefs on antibiotics and respiratory tract infections: An internet-based questionnaire study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2007, 57, 942–947. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18252068 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Department of Health Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018. 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/244058/20130902_UK_5_year_AMR_strategy.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Goff, D.A.; Kullar, R.; Goldstein, E.J.C.; Gilchrist, M.; Nathwani, D.; Cheng, A.C.; Cairns, K.A.; Escandón-Vargas, K.; Villegas, M.V.; Brink, A.; et al. A global call from five countries to collaborate in antibiotic stewardship: United we succeed, divided we might fail. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e56–e63. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1473309916303863 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Systems and Processes for Effective Antimicrobial Medicine Use (NICE Guideline 15). 2015. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng15 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Charani, E.; Castro-Sanchez, E.; Sevdalis, N.; Kyratsis, Y.; Drumright, L.; Shah, N.; Holmes, A. Understanding the Determinants of Antimicrobial Prescribing Within Hospitals: The Role of “Prescribing Etiquette”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, R.; Berry, D.; Sallis, A.; Chadborn, T. Behaviour Change and Antibiotic Prescribing in Healthcare Settings: Literature Review and Behavioural Analysis. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Richard_Pinder/publication/277937879_Behaviour_change_and_antibiotic_prescribing_in_healthcare_settings_Literature_review_and_behavioural_analysis/links/5576c6dc08ae7521586c7c37/Behaviour-change-and-antibiotic-prescribing-in-healthcare-settings-Literature-review-and-behavioural-analysis.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21513547 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McParland, J.L.; Williams, L.; Gozdzielewska, L.; Young, M.; Smith, F.; MacDonald, J.; Langdridge, D.; Davis, M.; Price, L. Flowers, P. What are the ’active ingredients’ of interventions targeting the public’s engagement with antimicrobial resistance and how might they work? Br. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23512568 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Changing Risk-Related Behaviours in the General Population (NICE Guideline 63). 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng63 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sinusitis (acute): Antimicrobial Prescribing (NICE Guideline 79). 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng79 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Public Health England. Antibiotic Awareness Key Messages. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/652262/Antibiotic_Awareness_Key_messages_2017.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sore Throat (Acute): Antimicrobial Prescribing (NICE Guideline 84). 2018. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Institute for Health and care Excellence. Infection prevention and control (Quality standard 61). 2014. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/search?q=QS61 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Public Health England. Management and Treatment of Common Infections: Antibiotic Guidance for Primary Care: For Consultation and Local Adaptation. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-common-infections-guidance-for-primary-care (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial Stewardship (Quality Standard 121). 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs121 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Institute for Health and care Excellence. Pneumonia in Adults: Diagnosis and Management (Clinical Guideline 191). 2014. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg191 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Quick Reference Guide: Antimicrobial Stewardship. 2017. Available online: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/antimicrobial-stewardship-ams-qrg (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Disposal of Unwanted Medicines. Available online: https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/essential-services/disposal-of-unwanted-medicines/ (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M. From Theory to Intervention: Mapping Theoretically Derived Behavioural Determinants to Behaviour Change Techniques. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 660–680. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Ladha, R.; Michie, S. From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: Comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 130–150. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24815766 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrt, T.; Bishop, J.; Carlin, J.B. Bias prevalence and kappa. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1993, 46, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2529310 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. Antibiotic Guardian. Available online: https://antibioticguardian.com (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, G., Education, Tools). Available online: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/targetantibiotics (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Antibiotic Action. Available online: http://antibiotic-action.com (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Treat Yourself Better. Available online: http://www.treatyourselfbetter.co.uk (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Department of Health Expert Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection and Public Health England. Antimicrobial Prescribing and Stewardship Competencies. 2013. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/253094/ARHAIprescrcompetencies__2_.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. The Learning Pharmacy. Available online: http://www.thelearningpharmacy.com (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and Infection Prevention Society (IPS). Infection Prevention and Control Commissioning Toolkit. 2020. Available online: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-005375#detailTab (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Healthcare CPD. Star: Stemming the Tide of Antibiotic Resistance. Available online: https://www.healthcarecpd.com/course/star-stemming-the-tide-of-antibiotic-resistance (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Royal College of General Pracitioners. Managing Acute Respiratory Tract Infections. Available online: http://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/info.php?id=17 (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Public Health England. Beat the Bugs. Available online: https://e-bug.eu/beat-the-bugs/ (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- NHS England. Patient Safety Alert—Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance through Implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme. 2015. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2015/08/psa-amr/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Public Health England. Keep Antibiotics Working. 2017. Available online: https://campaignresources.phe.gov.uk/resources/campaigns/58-keep-antibiotics-working/Overview (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- NHS England. Quality Premium: 2016/17 Guidance for CCGs. 2016. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ccg-out-tool/qual-prem/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Public Health England. Public Health Profiles. 2020. Available online: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- PrescQIPP. Antimicrobial Stewardship. Available online: https://www.prescqipp.info/our-resources/webkits/antimicrobial-stewardship/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Hallsworth, M.; Chadborn, T.; Sallis, A.; Sanders, M.; Berry, D.; Greaves, F.; Clements, L.; Davies, S.C. Provision of social norm feedback to high prescribers of antibiotics in general practice: A pragmatic national randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self Care Forum. Self Care Week. Available online: http://www.selfcareforum.org/events/self-care-week-resources/ (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Public and International Health Directorate Health Protection and Emergency Response Division, I.D.B. The Health and Social Care Act 2008 Code of Practice of the Prevention and Control of Infections and Related Guidance. 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/449049/Code_of_practice_280715_acc.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- National Health Service. Common Cold. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/common-cold/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. Antibacterial Resistance—A Global Threat to Public Health: The Role of the Pharmacy Team. A CPPE distance learning programme. 2014. Available online: https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/antibacres-p-01/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- UKCPA Expert Professional Curriculum for Antimicrobial Pharmacists. Available online: http://bsac.org.uk/ukcpa-expert-professional-curriculum-for-antimicrobial-pharmacists/ (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- FeverPAIN. Available online: https://ctu1.phc.ox.ac.uk/feverpain/index.php (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Respiratory Tract Infections (Self-Limiting): Prescribing Antibiotics Clinical Guideline [cg69]. 2008. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69 (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Self Care Forum. Factsheets. Available online: http://www.selfcareforum.org/fact-sheets/fact-sheets-2020/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- OpenPrescribing.net. EBM DataLab: University of Oxford. 2020. Available online: https://openprescribing.net (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis. Available online: https://www.mdcalc.com/centor-score-modified-mcisaac-strep-pharyngitis (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Health Education England. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Guide for GPs. 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PkYQJettZVo (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Department of Health and Social Care. Take Care not Antibiotics. 2011. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8jdLQSUHKsg (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Patient.info. Available online: https://patient.info/ears-nose-throat-mouth (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Health Education England. Awareness of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Animation. 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oMnU6g2djm4 (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Ward, C. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to optimise antibiotic use in a primary care urgent care centre setting. BMJ Open Qual. 2018, 7, e000391. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6203029/ (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).