Polymer Coatings Based on Polyisobutylene, Polystyrene and Poly(styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) for Effective Protection of MXenes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MAX Phase and MXene Synthesis

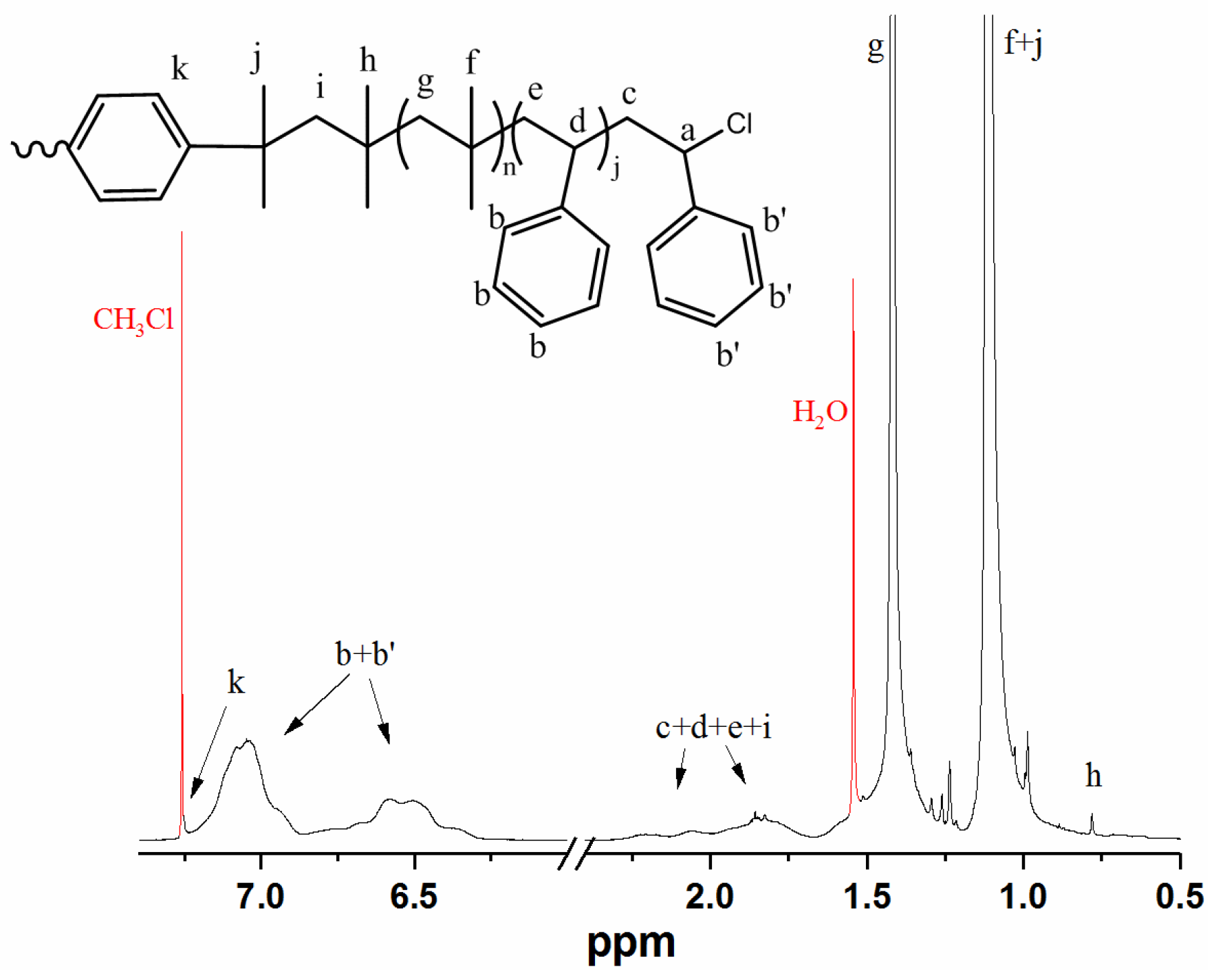

2.2. Polymer Synthesis

2.3. Preparation of MXene Films

2.4. Preparation of Polymer Coating on MXene

2.5. Characterization

2.6. Stability Test at Ambient Conditions

3. Results and Discussion

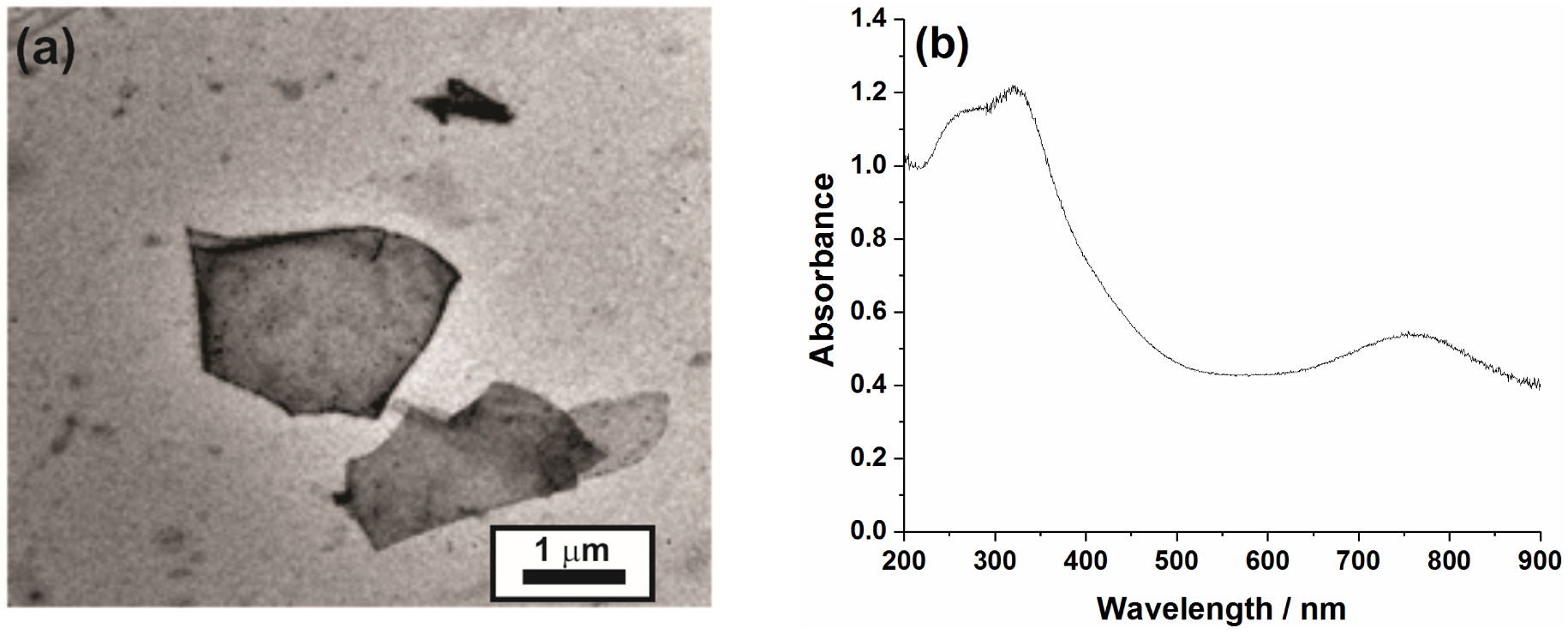

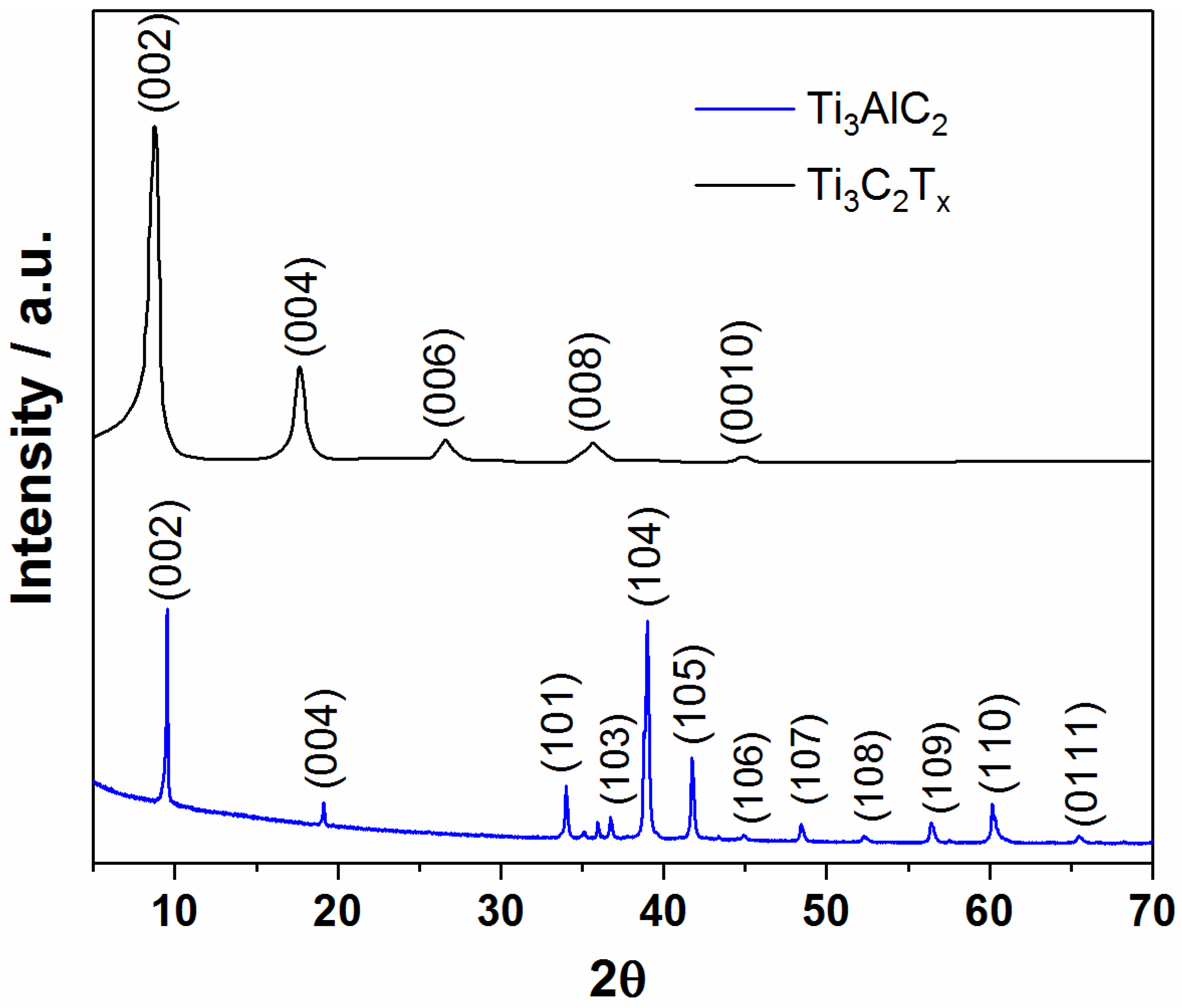

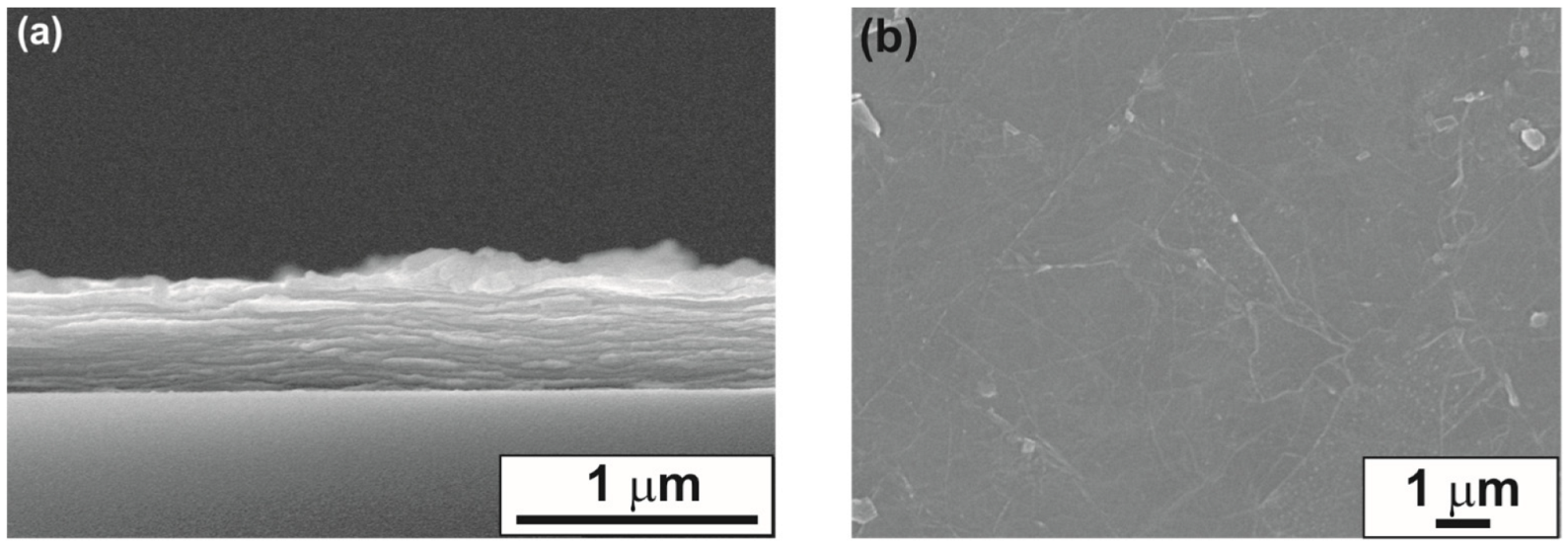

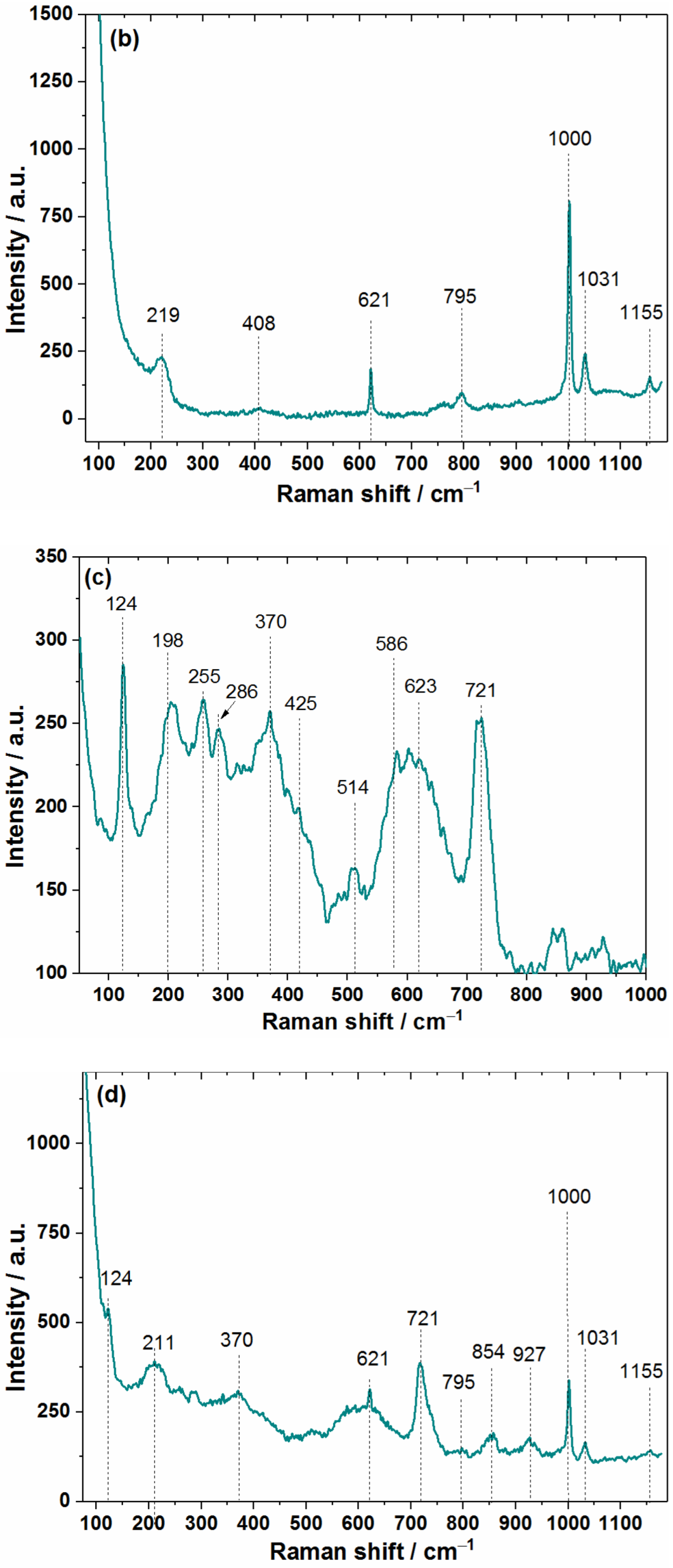

3.1. Structural and Morphological Characterization of MXene Samples

3.2. Characterization of MXene–Polymer Interface

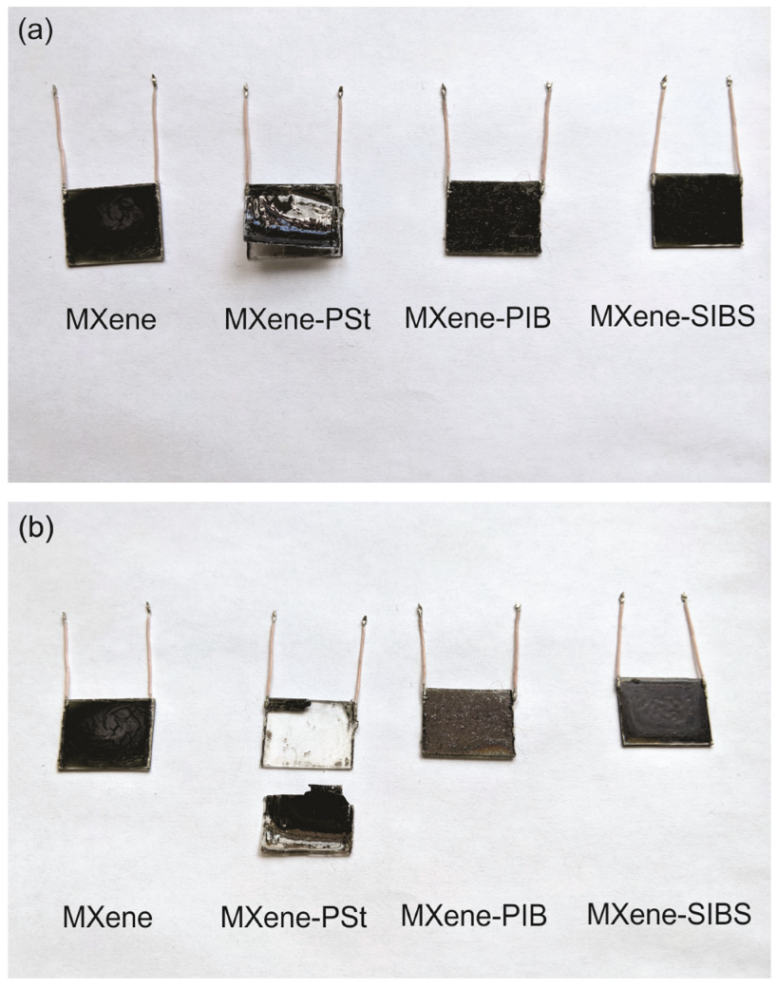

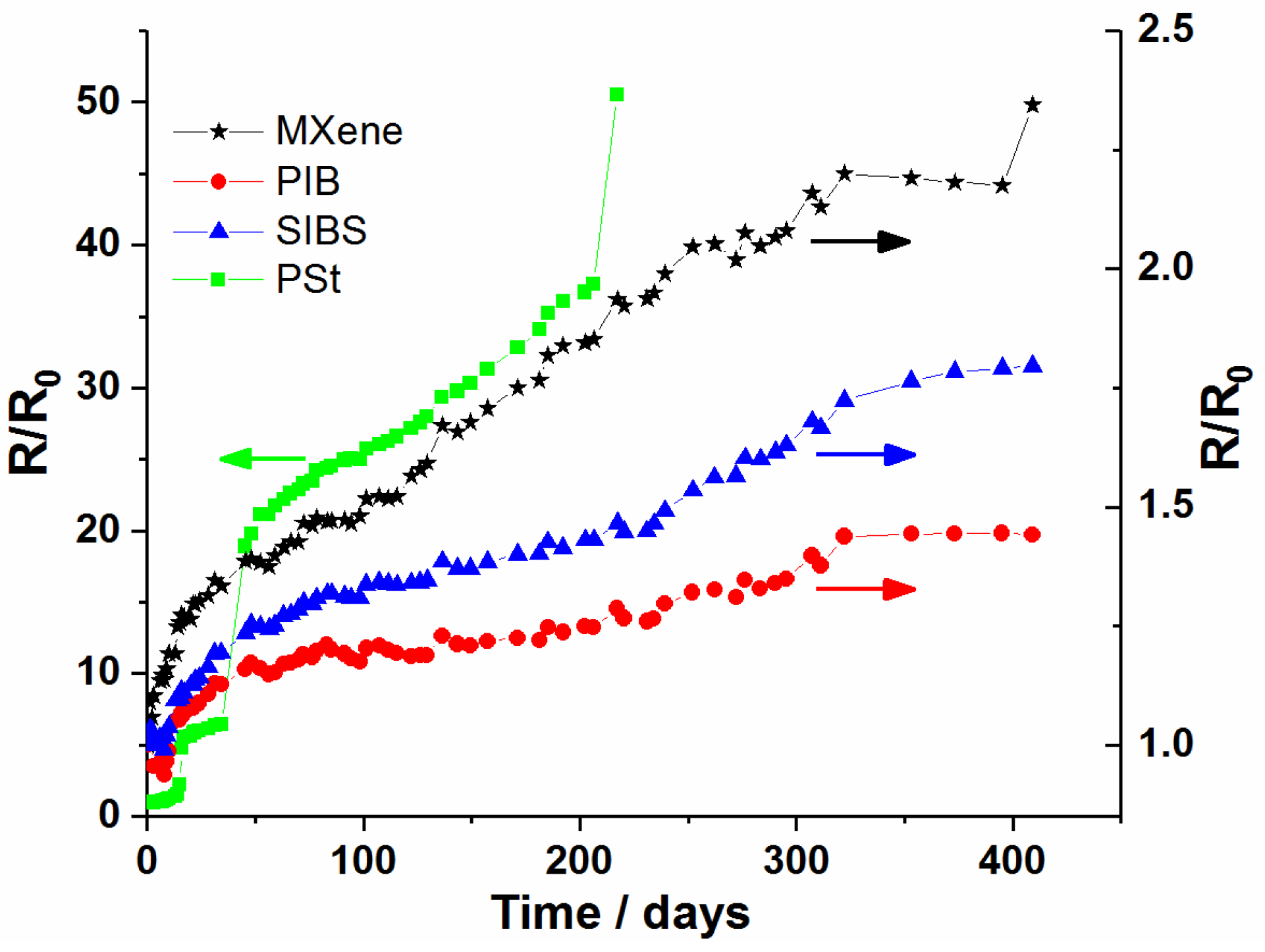

3.3. Protection of MXene Films against Oxidation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Shuck, C.E.; Sarycheva, A.; Anayee, M.; Levitt, A.; Zhu, Y.; Uzun, S.; Balitskiy, V.; Zahorodna, V.; Gogotsi, O.; Gogotsi, Y. Scalable Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 1901241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabeb, M.; Maleski, K.; Anasori, B.; Lelyukh, P.; Clark, L.; Sin, S.; Gogotsi, Y. Guidelines for Synthesis and Processing of Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7633–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, G.; Rawal, J.; Modigunta, J.K.R.; Park, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J.; In, I. A Review on MXenes: New-Generation 2D Materials for Supercapacitors. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 5672–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.C.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z. Recent Advances in MXene: Preparation, Properties, and Applications. Front. Phys. 2015, 10, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Anasori, B. The Rise of MXenes. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8491–8494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, Z.; Lu, C.; Cao, X.; Zhang, P.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Sha, D.; He, W.; Zhang, W.; Pan, L.; et al. Role of MXene Surface Terminations in Electrochemical Energy Storage: A Review. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 2648–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, R.M.; Arantes, J.T.; Santos, S.F. Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications of MXenes: Current Status and Perspectives. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 18167–18188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Shuck, C.E.; Liang, G.; Gogotsi, Y.; Zhi, C. MXene Chemistry, Electrochemistry and Energy Storage Applications. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ran, F.; Yang, F.; Long, J.; Shao, L. Advances in MXene Films: Synthesis, Assembly, and Applications. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2021, 27, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Xue, J.; Ding, L.X.; Wang, S.; Caro, J.; Gogotsi, Y. MXene Molecular Sieving Membranes for Highly Efficient Gas Separation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Choi, J.; Maleski, K.; Hantanasirisakul, K.; Jung, H.T.; Gogotsi, Y.; Ahn, C.W. Interfacial Assembly of Ultrathin, Functional Mxene Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 32320–32327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, F.; Alhabeb, M.; Hatter, C.B.; Anasori, B.; Hong, S.M.; Koo, C.M.; Gogotsi, Y. Electromagnetic Interference Shielding with 2D Transition Metal Carbides (MXenes). Science 2016, 353, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, A.; Hong, J.; Ko, T.Y.; Koo, C.M. Improving Oxidation Stability of 2D MXenes: Synthesis, Storage Media, and Conditions. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, F.; Lao, J.; Yu, R.; Sang, X.; Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Ambient Oxidation of Ti3C2 MXene Initialized by Atomic Defects. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 23330–23337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, T.; Zhao, X.; Shah, S.A.; Chen, Y.; Sun, W.; An, H.; Lutkenhaus, J.L.; Radovic, M.; Green, M.J. Oxidation Stability of Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets in Solvents and Composite Films. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2019, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chae, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, S.Y.; Choi, J.; Maleski, K.; Lee, B.J.; Jung, H.T.; Gogotsi, Y.; Lee, Y.; Ahn, C.W. An Investigation into the Factors Governing the Oxidation of Two-Dimensional Ti3C2 MXene. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 8387–8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Pinilla, S.; McEvoy, N.; Cullen, C.P.; Anasori, B.; Long, E.; Park, S.H.; Seral-Ascaso, A.; Shmeliov, A.; Krishnan, D.; et al. Oxidation Stability of Colloidal Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbides (MXenes). Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 4848–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Mochalin, V.N. Hydrolysis of 2D Transition-Metal Carbides (MXenes) in Colloidal Solutions. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 1958–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lim, Y.; Chae, Y.; Lee, B.J.; Kim, Y.T.; Han, H.; Gogotsi, Y.; Ahn, C.W. Oxidation-Resistant Titanium Carbide MXene Films. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Holta, D.E.; Tan, Z.; Oh, J.H.; Echols, I.J.; Anas, M.; Cao, H.; Lutkenhaus, J.L.; Radovic, M.; Green, M.J. Annealed Ti3C2TzMXene Films for Oxidation-Resistant Functional Coatings. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 10578–10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Ren, C.E.; Zhao, M.Q.; Yang, J.; Giammarco, J.M.; Qiu, J.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. Flexible and Conductive MXene Films and Nanocomposites with High Capacitance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16676–16681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hatter, C.B.; Shah, J.; Anasori, B.; Gogotsi, Y. Micromechanical Response of Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Carbonitride (MXene) Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 182, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Sohn, M.; Ma, R.; Kang, D.J. Flexible Single-Electrode Triboelectric Nanogenerators with MXene/PDMS Composite Film for Biomechanical Motion Sensors. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Che, R.; Zheng, G.; Liu, C.; Shen, C.; Liu, X. Ultrathin Flexible Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride)/MXene/Silver Nanowire Film with Outstanding Specific EMI Shielding and High Heat Dissipation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2021, 4, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Shen, J.; Hu, Q.; Nie, W.; Wang, Z.; Zou, L.; Li, C. Vapor Phase Polymerized Conducting Polymer/MXene Textiles for Wearable Electronics. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 1832–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, C.; Wei, Y.; Li, J. Preparation Strategies and Applications of MXene-Polymer Composites: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, K.; Zhou, K.; Qian, X.; Shi, C.; Yu, B. MXene as Emerging Nanofillers for High-Performance Polymer Composites: A Review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 217, 108867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.; Hou, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, G. Preparation and Characterization of Epoxy Resin Filled with Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets with Excellent Electric Conductivity. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, I.; Din, M.F.U.; Gu, Z.-G. MXenes Thin Films: From Fabrication to Their Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiong, J.; Du, S.; Zhang, P.; Shi, X.; Yu, J. MXene/Polymer Nanocomposites: Preparation, Properties, and Applications. Polym. Rev. 2021, 61, 80–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimmy, J.; Kandasubramanian, B. Mxene Functionalized Polymer Composites: Synthesis and Applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 122, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayari, V.; Hemsworth, N.; Fakih, I.; Favron, A.; Gaufrès, E.; Gervais, G.; Martel, R.; Szkopek, T. Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in a Black Phosphorus Naked Quantum Well. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, L.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J. Recent Advances in Oxidation and Degradation Mechanisms of Ultrathin 2D Materials under Ambient Conditions and Their Passivation Strategies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 4291–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesyuk, R.; Cai, B.; Reuter, U.; Gaponik, N.; Popovych, D.; Lesnyak, V. Quantum-Dot-in-Polymer Composites via Advanced Surface Engineering. Small Methods 2017, 1, 1700189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Deng, X.; Xie, Z.; Cai, X.; Liang, S.; Ma, P.; Hou, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, J. Enhancing the Stability of Perovskite Quantum Dots by Encapsulation in Crosslinked Polystyrene Beads via a Swelling–Shrinking Strategy toward Superior Water Resistance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1703535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Floch, P.; Meixuanzi, S.; Tang, J.; Liu, J.; Suo, Z. Stretchable Seal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 27333–27343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiman, D.I.; Sayevich, V.; Meerbach, C.; Nikishau, P.A.; Vasilenko, I.V.; Gaponik, N.; Kostjuk, S.V.; Lesnyak, V. Robust Polymer Matrix Based on Isobutylene (Co)Polymers for Efficient Encapsulation of Colloidal Semiconductor Nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarevich, M.I.; Nikishau, P.A.; Berezianko, I.A.; Glushkova, T.V.; Rezvova, M.A.; Ovcharenko, E.A.; Bekmukhamedov, G.E.; Yakhvarov, D.G.; Kostjuk, S.V. Aspects of the Synthesis of Poly(Styrene-Block-Isobutylene-Block-Styrene) by TiCl4-Co-Initiated Cationic Polymerization in Open Conditions. Macromol 2021, 1, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Liu, X.L.; Lin, M.L.; Tan, P.H. Application of Raman Spectroscopy to Probe Fundamental Properties of Two-Dimensional Materials. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarycheva, A.; Gogotsi, Y. Raman Spectroscopy Analysis of the Structure and Surface Chemistry of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Hu, M.; Wang, X. Vibrational Properties of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2T2 (T = O, F, OH) Monosheets by First-Principles Calculations: A Comparative Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 9997–10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presser, V.; Naguib, M.; Chaput, L.; Togo, A.; Hug, G.; Barsoum, M.W. First-Order Raman Scattering of the MAX Phases. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2012, 43, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, T.E.; Houlne, M.P.; Harris, J.M. Spatially Resolved Analysis of Small Particles by Confocal Raman Microscopy: Depth Profiling and Optical Trapping. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maltanava, H.; Shiman, D.; Ovodok, E.; Svito, I.; Makarevich, M.; Kostjuk, S.; Poznyak, S.; Aniskevich, A. Polymer Coatings Based on Polyisobutylene, Polystyrene and Poly(styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) for Effective Protection of MXenes. Coatings 2022, 12, 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12101477

Maltanava H, Shiman D, Ovodok E, Svito I, Makarevich M, Kostjuk S, Poznyak S, Aniskevich A. Polymer Coatings Based on Polyisobutylene, Polystyrene and Poly(styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) for Effective Protection of MXenes. Coatings. 2022; 12(10):1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12101477

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaltanava, Hanna, Dmitriy Shiman, Evgeni Ovodok, Ivan Svito, Miraslau Makarevich, Sergei Kostjuk, Sergey Poznyak, and Andrey Aniskevich. 2022. "Polymer Coatings Based on Polyisobutylene, Polystyrene and Poly(styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) for Effective Protection of MXenes" Coatings 12, no. 10: 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12101477