Impact of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Substrate Phase Transitions Induced by Extreme Temperature Variations on the Tribological Properties of TiN Thin Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Characterization Methods

2.3. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phase Transitions of NiTi Substrate

3.2. Thin Film Microstructure

3.3. Thin Film and Substrate Phase Composition

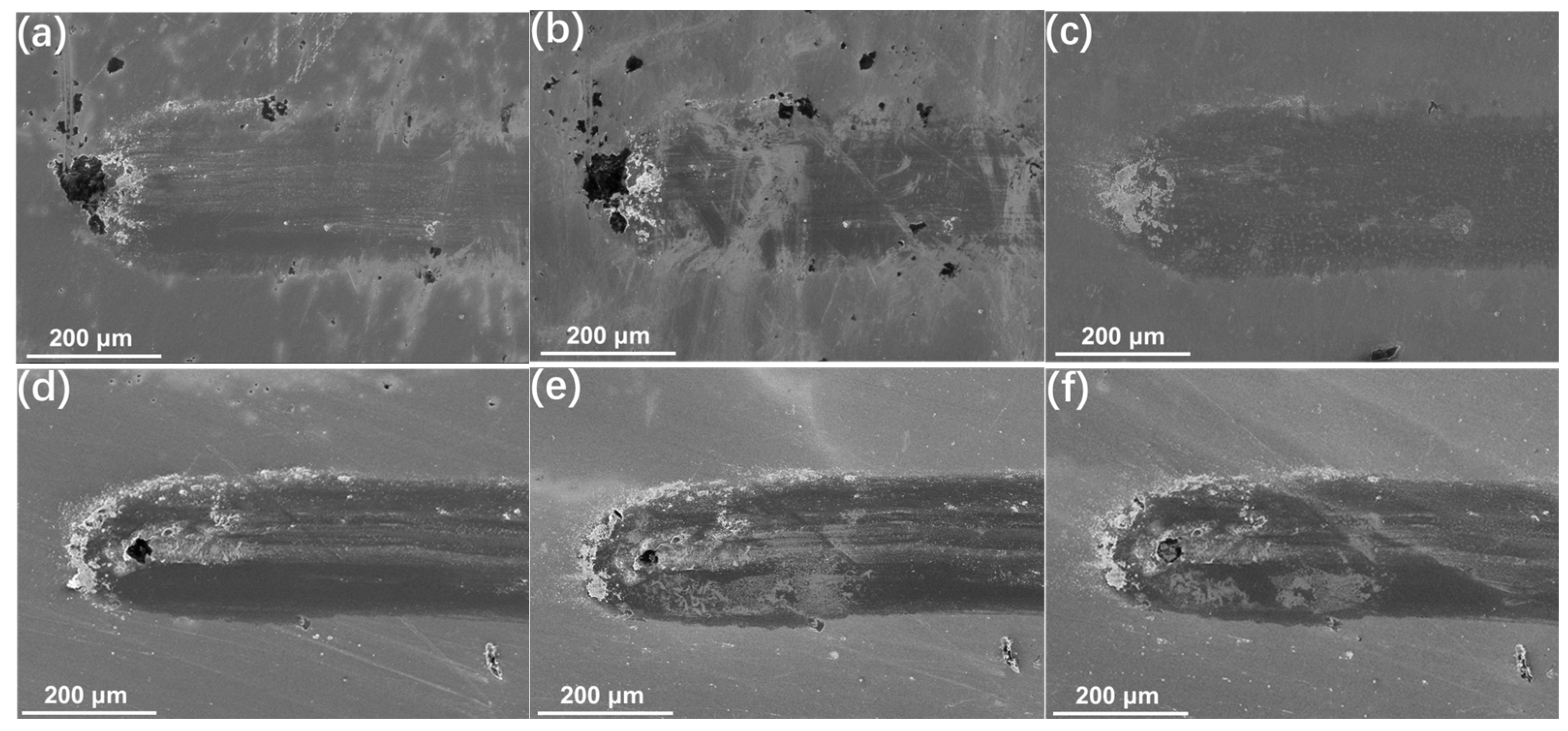

3.4. Wear Mechanism of TiN Film

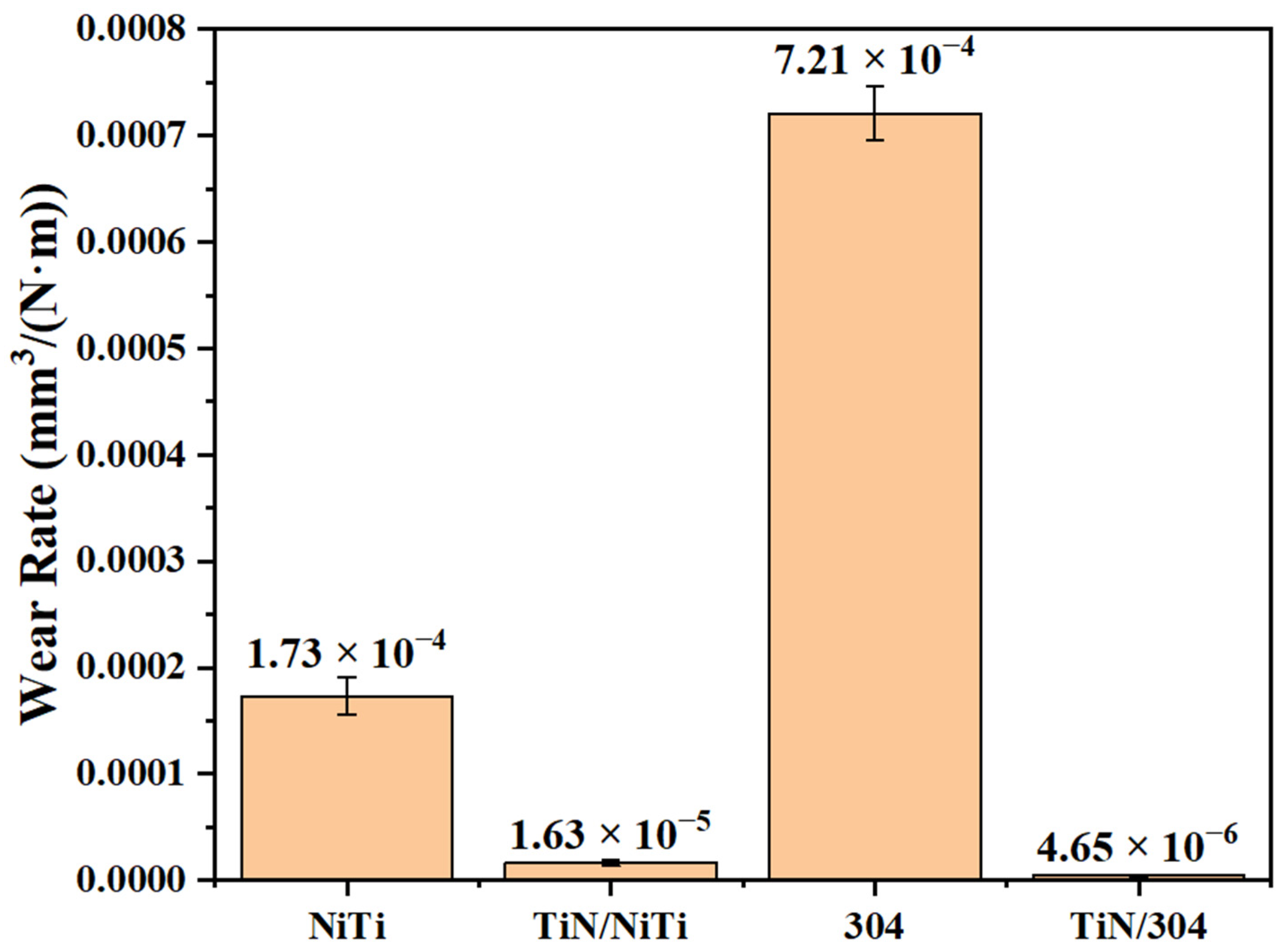

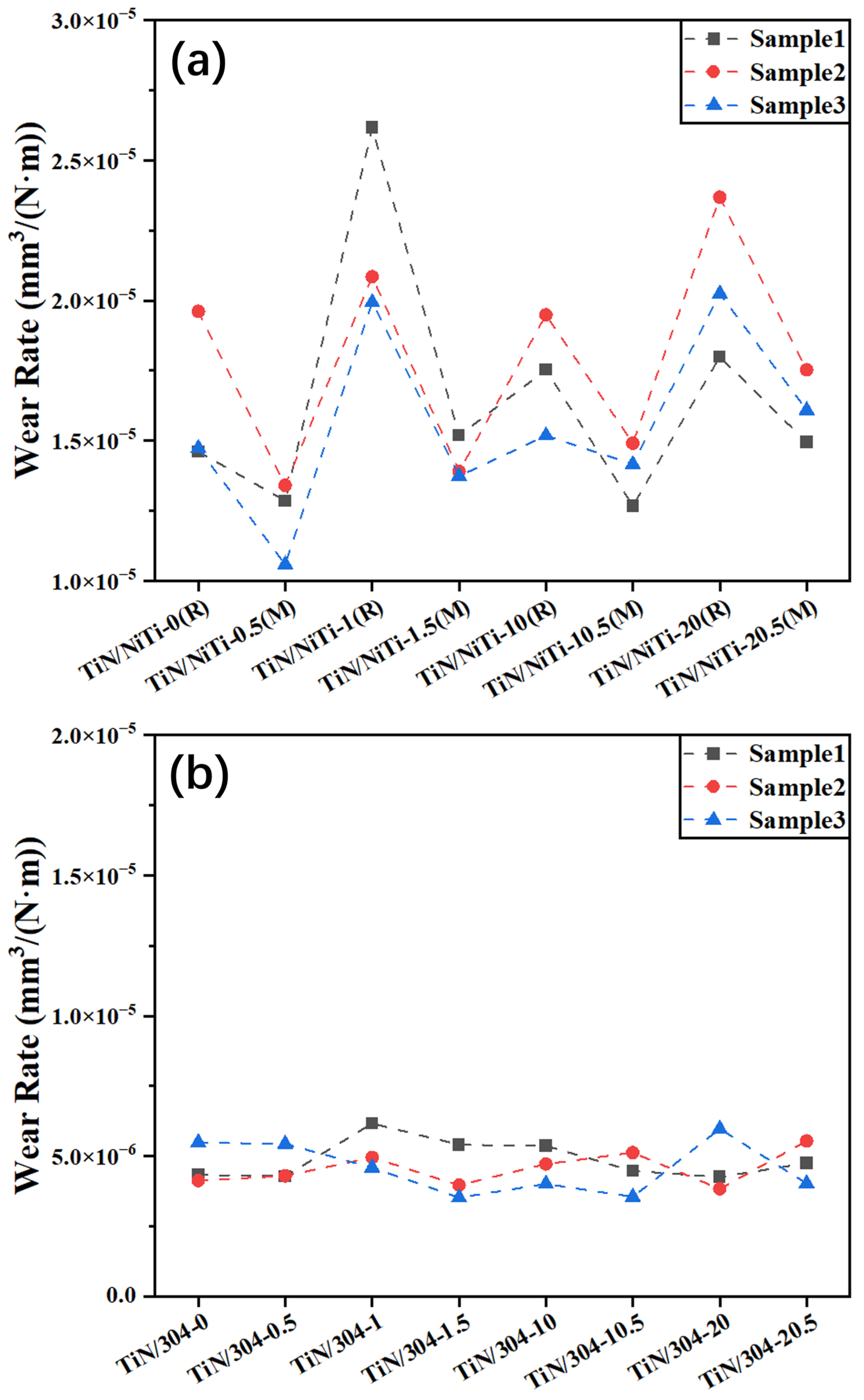

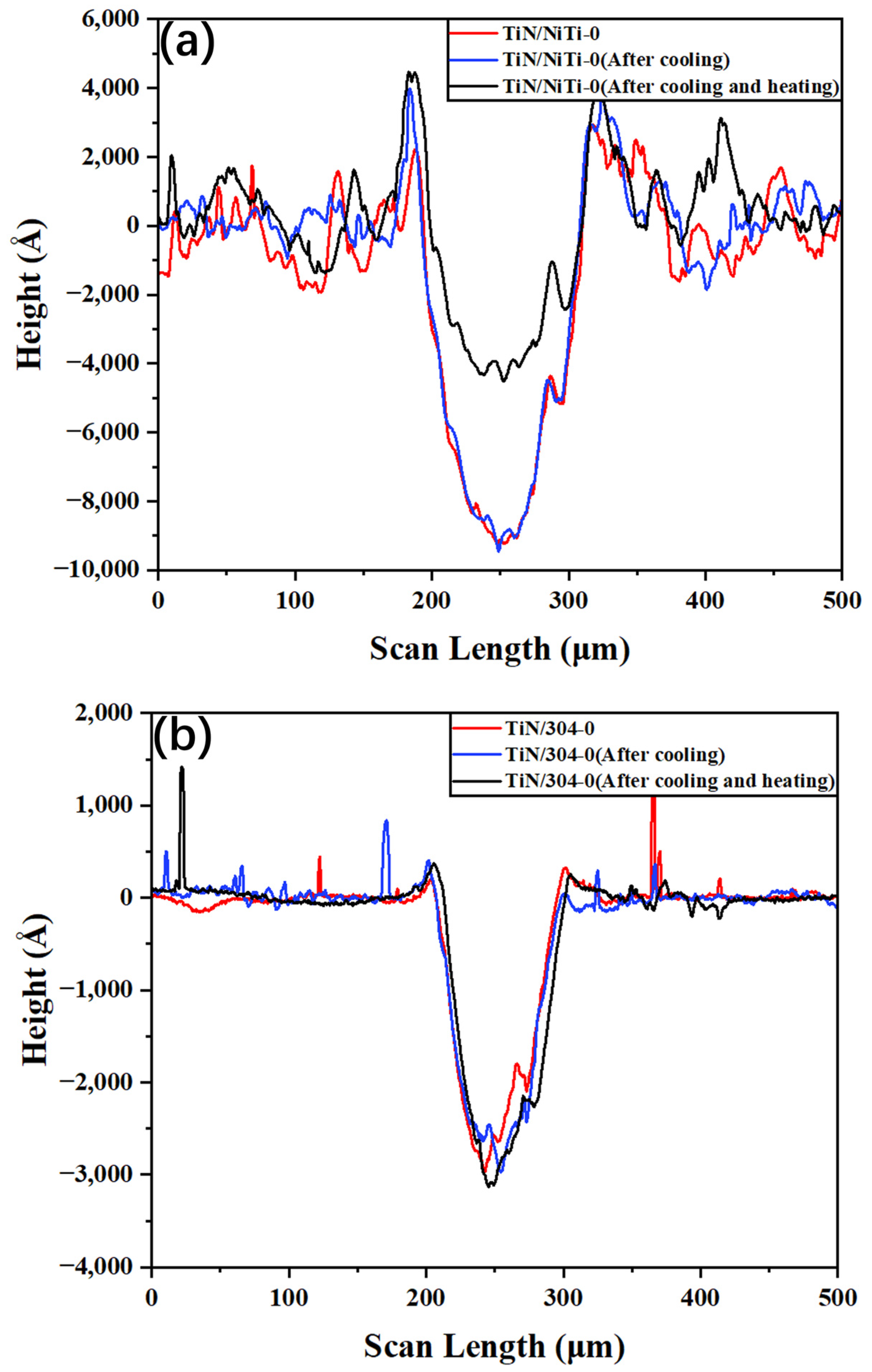

3.5. Wear Rate of TiN Thin Film

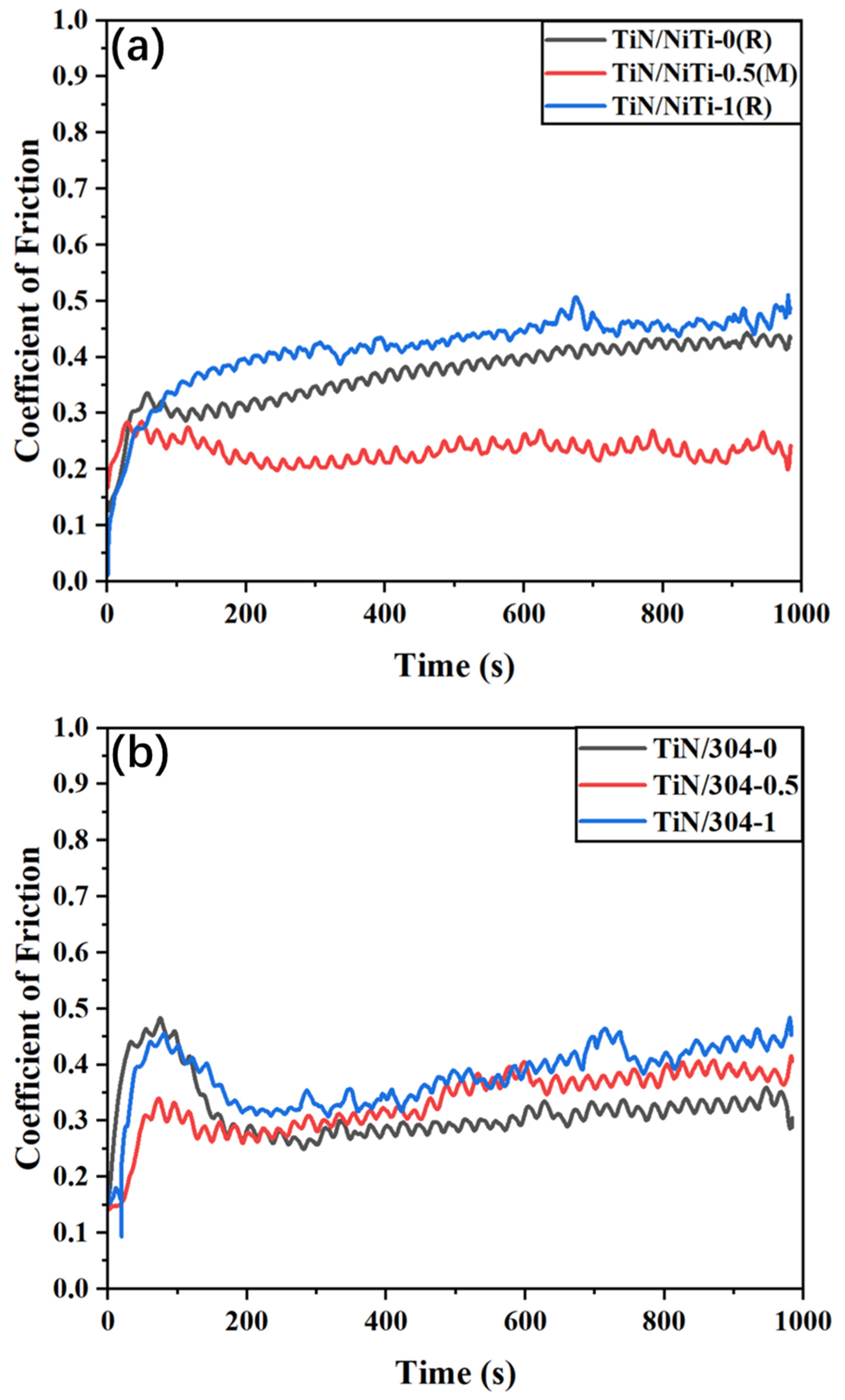

3.6. Coefficient of Friction of Composites

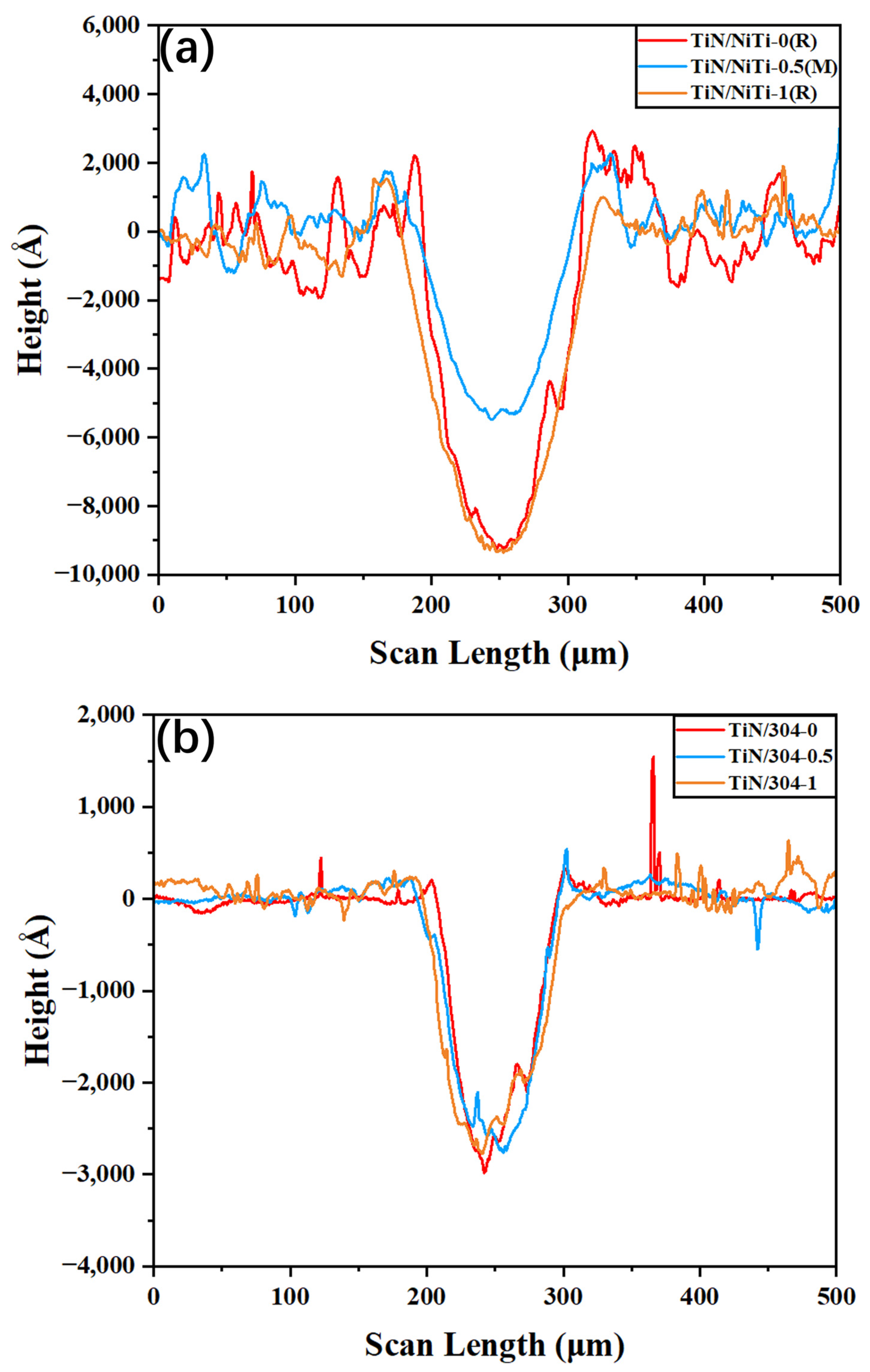

3.7. Evolution of Wear Scar Characteristics on TiN/NiTi Alloy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Farber, E.; Zhu, J.-N.; Popovich, A.; Popovich, V. A review of NiTi shape memory alloy as a smart material produced by additive manufacturing. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 30, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Naceur, I.; Elleuch, K. Tribological properties of deflected NiTi superelastic archwire using a new experimental set-up: Stress-induced martensitic transformation effect. Tribol. Int. 2020, 146, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Naceur, I.B.; Elleuch, K. Effects of saliva addition on the wear resistance of deflected NiTi archwire for biomedical application. Mater. Lett. 2020, 268, 127550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Kong, D.; Wang, S.; Cao, G.-Z.; Liu, C. In-Vitro Investigation on the Tribological Properties of Nickel-Titanium (NiTi) Alloy Used in Braided Vascular Stents. Tribol. Trans. 2024, 67, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, G.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Zheng, D.; Chung, C.Y.; Xu, Z.S.; Chu, P.K. Wear mechanism and tribological characteristics of porous NiTi shape memory alloy for bone scaffold. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 2586–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zheng, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H. Enhanced mechanical properties and structural stability of HF-Modified NITI alloy for advanced bearing materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yan, H.; Zhang, P.; Lu, Q.; Shi, H. Fabrication and tribological properties of bionic surface texture self-lubricating 60NiTi alloy via selective laser melting and infiltration. Tribol. Int. 2025, 202, 110364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezaack, M.B.; Simar, A.; Marchal, Y.; Steinmetz, M.; Faes, K.; Pacheco de Almeida, J.P. Dissimilar friction welding of NiTi shape memory alloy and steel reinforcing bars for seismic performance. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2022, 27, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; Xu, Y.; Yu, C.; Kang, G. Functional fatigue of superelasticity and elastocaloric effect for NiTi springs. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 265, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, H.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Lou, J.; He, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y. Large thermal hysteresis NiTi Belleville washer fabricated by metal injection moulding. Powder Met. 2020, 63, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokoun, D.; Pilch, J.; Kadeřávek, L.; Šittner, P. Strength of superelastic NITI Velcro-Like Fasteners. Metals 2021, 11, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksöz, S. Wear behavior of hot forged NITI parts produced by PM Technique. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2019, 72, 1949–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, S.; Cibulková, J.; Čtvrtlík, R.; Tomáštík, J.; Václavek, L.; Kopeček, J.; Šittner, P. Tribological behavior of NITI alloy produced by spark plasma sintering Method. Coatings 2021, 11, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, W. Improvement of TiN coating on comprehensive performance of NiTi alloy braided vascular stent. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 13405–13413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Wu, C.; Sun, Z. Tailoring the surface of NiTi alloy by TiN coating for biomedical application. Mater. Technol. 2017, 32, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.; Huang, J.J.; Kang, T.; Diao, D.F.; Duan, Y.Z. Coating NiTi archwires with diamond-like carbon films: Reducing fluoride-induced corrosion and improving frictional properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Zhou, D.; He, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C. Graphene oxide nanocoating for enhanced corrosion resistance, wear resistance and antibacterial activity of nickel-titanium shape memory alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 431, 128012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Miller, C.; Zou, M. Tribological performance of PDA/PTFE + graphite particle coatings on 60NiTi. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 527, 146731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, Q.; Xing, X. Tribological performance of hydrogenated diamond-like carbon coating deposited on superelastic 60NiTi alloy for aviation self-lubricating spherical plain bearings. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, H.-H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.-Q. Influence of Ni4Ti3 precipitation on martensitic transformations in NiTi shape memory alloy: R phase transformation. Acta Mater. 2021, 207, 116665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, S.; Jin, Y.; Meng, X. Nanoscale interwoven structure of B2 and R-phase in NiTi alloy film. Vacuum 2016, 129, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.A.; Kyriakides, S. On the nucleation and propagation of phase transformation fronts in a NiTi alloy. Acta Mater 1997, 45, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Hou, M.; Su, Y.; Wei, L.; Wang, X.; Guan, M.; Leng, Y. Effect of NiTi phase transitions induced by cryogenic-thermal cycle treatment on the bonding strength evolution of the TiN-NiTi interface1. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Gao, J.; Si, C.; Yao, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y. Tribological properties of TIN coating on cotton picker spindle. Coatings 2023, 13, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Bai, Y.; Gao, K.; Pang, X.; Yang, H.; Yan, L.; Volinsky, A.A. Residual stress and microstructure effects on mechanical, tribological and electrical properties of TiN coatings on 304 stainless steel. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 15851–15858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Jiang, D.; Gao, X.; Hu, M.; Wang, D.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J.; Feng, D.; Weng, L. Friction and wear behavior of TiN films against ceramic and steel balls. Tribol. Int. 2018, 124, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossnagel, S.M. Magnetron sputtering. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 060805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Qi, F.; Ouyang, X.; Zhao, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; Luo, W.; Liao, B.; Luo, J. Effect of TI transition layer thickness on the structure, mechanical and adhesion properties of TI-DLC coatings on aluminum alloys. Materials 2018, 11, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.I.; Park, H.K.; An, S.; Hong, S.J. Plasma ion bombardment induced heat flux on the wafer surface in inductively coupled plasma reactive ion ETCH. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motomura, T.; Takemura, K.; Nagase, T.; Morita, N.; Tabaru, T. Suppression of substrate temperature in DC magnetron sputtering deposition by magnetic mirror-type magnetron cathode. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 025153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, O.O.; Lahouij, M.; Jaghar, N.; Larhlimi, H.; Makha, M.; Alami, J. Synergistic effect of deposition temperature and substrate bias on structural, mechanical, stability and adhesion of TiN thin film prepared by reactive HiPIMS. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 10593–10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xi, Y.; Meng, J.; Pang, X.; Yang, H. Effects of substrate bias voltage on mechanical properties and tribological behaviors of RF sputtered multilayer TiN/CrAlN films. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 665, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchil, J.; Fernandes, F.M.B.; Mahesh, K.K. X-ray diffraction study of the phase transformations in NiTi shape memory alloy. Mater. Charact. 2007, 58, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.-M.; Nie, X.; Yu, S. Study on failure mechanisms of DLC coated Ti6Al4V and CoCr under cyclic high combined contact stress. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Jing, P.; Leng, Y. Effect of carbon content on structure and properties of (CuNiTiNbCr)CxNy high-entropy alloy films. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 4073–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, S.; Yıldız, B.; Ürgen, M. Orientation dependent tribological behavior of TiN coatings. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2016, 28, 134009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciniegas, M.; Casals, J.; Manero, J.M.; Peña, J.; Gil, F.J. Study of hardness and wear behaviour of NiTi shape memory alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 460, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, X.M.; Li, Y.T.; Zeng, X.K.; Jiang, X.; Leng, Y.X. HiPIMS deposition of CuNiTiNbCr high—Entropy alloy films: Influence of the pulse width on structure and properties. Vacuum 2023, 217, 112546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-H.; Wu, F.-B. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of refractory molybdenum-tungsten nitride coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 476, 130154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viloan, R.P.B.; Gu, J.; Boyd, R.; Keraudy, J.; Li, L.; Helmersson, U. Bipolar high power impulse magnetron sputtering for energetic ion bombardment during TiN thin film growth without the use of a substrate bias. Thin Solid Films 2019, 688, 137350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, M.; Ghasemi, H.M.; Nili Ahmadabadi, M.N. Self-healing effect on worn surface of NiTi shape memory alloy. Mater Sci Technol 2010, 26, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Cheng, Y.-T.; Grummon, D.S. Wear resistant self-healing tribological surfaces by using hard coatings on NiTi shape memory alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ms | Mf | As | Af | Rs | Rf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 25 °C | −3 °C | 45 °C | 68 °C | 54 °C | 38 °C |

| Ar:N2 Ratio | Power Supply | Substrate Bias/V | Target–Substrate Distance/mm | Working Pressure/Pa | Working Time/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti transition layer | 40:0 | DC-2A | −50 | 90 | 0.53 | 2 |

| TiN layer | 40:10 | DC-2A | −50 | 90 | 0.61 | 25 |

| Sample Coding | Sample Information |

|---|---|

| TiN/substrate-0 | The sample underwent friction in its initial state. |

| TiN/substrate-0.5 | The sample underwent friction after one deep-cryogenic treatment. |

| TiN/substrate-1 | The sample underwent friction after one cryogenic–thermal cycle treatment. |

| TiN/substrate-1.5 | The sample underwent friction after one cryogenic–thermal cycle treatment with an additional deep-cryogenic treatment. |

| TiN/substrate-10 | The sample underwent friction after ten cryogenic–thermal cycle treatments. |

| TiN/substrate-10.5 | The sample underwent friction after ten cryogenic–thermal cycle treatments with an additional deep-cryogenic treatment. |

| TiN/substrate-20 | The sample underwent friction after twenty cryogenic–thermal cycle treatments. |

| TiN/substrate-20.5 | The sample underwent friction after twenty cryogenic–thermal cycle treatments with an additional deep-cryogenic treatment. |

| TiN/substrate-0(0.5) | The sample underwent friction in its initial state and then underwent one deep-cryogenic treatment. |

| TiN/substrate-0(1) | The sample underwent friction in its initial state and then underwent one cryogenic–thermal cycle treatment. |

| β/° | 2θ/° | Grain Size/nm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiN/NiTi-0 | 0.46 | 36.50 | 18.09 |

| TiN/NiTi-0.5 | 0.45 | 36.52 | 18.40 |

| TiN/NiTi-1 | 0.45 | 36.50 | 18.50 |

| TiN/304-0 | 0.27 | 36.59 | 31.14 |

| TiN/304-0.5 | 0.26 | 36.49 | 31.44 |

| TiN/304-1 | 0.26 | 36.46 | 31.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, M.; Xie, D.; Wang, X.; Guan, M.; Ren, D.; Su, Y.; Ma, D.; Leng, Y. Impact of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Substrate Phase Transitions Induced by Extreme Temperature Variations on the Tribological Properties of TiN Thin Films. Coatings 2025, 15, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020155

Hou M, Xie D, Wang X, Guan M, Ren D, Su Y, Ma D, Leng Y. Impact of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Substrate Phase Transitions Induced by Extreme Temperature Variations on the Tribological Properties of TiN Thin Films. Coatings. 2025; 15(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Mingxi, Dong Xie, Xiaoting Wang, Min Guan, Diqi Ren, Yongyao Su, Donglin Ma, and Yongxiang Leng. 2025. "Impact of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Substrate Phase Transitions Induced by Extreme Temperature Variations on the Tribological Properties of TiN Thin Films" Coatings 15, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020155

APA StyleHou, M., Xie, D., Wang, X., Guan, M., Ren, D., Su, Y., Ma, D., & Leng, Y. (2025). Impact of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Substrate Phase Transitions Induced by Extreme Temperature Variations on the Tribological Properties of TiN Thin Films. Coatings, 15(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020155