Plant Use Adaptation in Pamir: Sarikoli Foraging in the Wakhan Area, Northern Pakistan

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

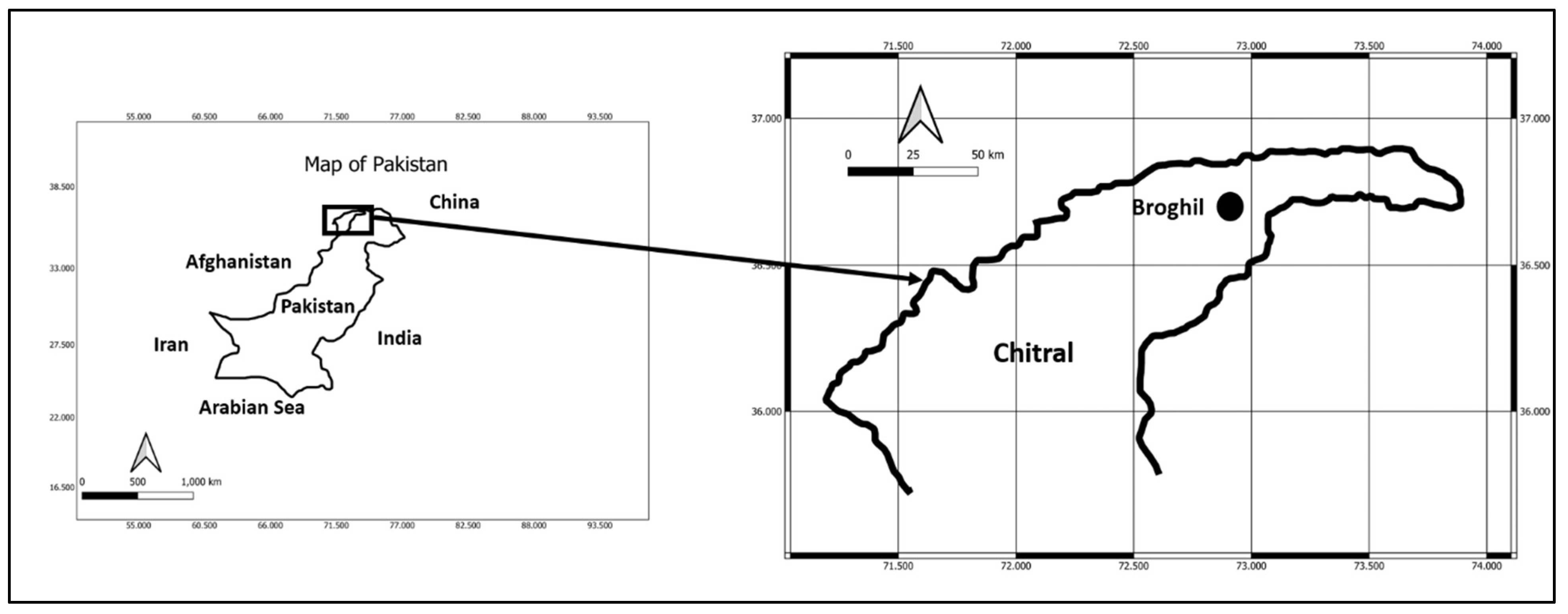

2.1. Study Area and Communities

2.2. Ethnobotanical Survey

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. WFPs and Their Uses

3.2. Comparison with Neighboring Regions

3.3. Political Boundaries: Threats to Cultural Resilience

3.4. Provision of Subsidies to Local Communities: Promotion of Ecotourism

4. Conclusions and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hornberger, N. Language policy, language education, language rights: Indigenous, immigrant, and international perspectives. Lang. Soc. 1998, 27, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E. Multilingualism and the family. In Handbook of Multilingualism and Multilingual Communication; Auer, P., Li, W., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UNDESA). International Migration Report 2015: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/375); United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UNDESA): Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Contexts of acculturation. In Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Sam, D.L., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Raikhan, S.; Moldakhmet, M.; Ryskeldy, M.; Alua, M. The interaction of globalization and culture in the modern world. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bharucha, Z.; Pretty, J. The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2913–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eberhard, D.M.; Simons, G.F.; Fennig, C.D. (Eds.) Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 24th ed.; SIL International: Dallas, TX, USA, 2021; Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Aziz, M.A.; Abbasi, A.M.; Ullah, Z.; Pieroni, A. Shared but Threatened: The Heritage of Wild Food Plant Gathering among Different Linguistic and Religious Groups in the Ishkoman and Yasin Valleys, North Pakistan. Foods 2020, 9, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Ullah, Z.; Pieroni, A. Wild Food Plant Gathering among Kalasha, Yidgha, Nuristani and Khowar Speakers in Chitral, NW Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Ullah, Z.; Adnan, M.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. The Fading Wild Plant Food–Medicines in Upper Chitral, NW Pakistan. Foods 2021, 10, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soelberg, J.; Jäger, A.K. Comparative ethnobotany of the Wakhi agropastoralist and the Kyrgyz nomads of Afghanistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, A.A. Effect and impact of indigenous knowledge on local biodiversity and social resilience in Pamir region of Tajik and Afghan Badakhshan. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021, 22, 1–26. Available online: https://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/2999 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Karamkhudoeva, M.; Laldjebaev, M.; Ruelle, M.L.; Kassam, K.A.S. Medicinal Plants and Health Sovereignty in Badakhshan, Afghanistan: Diversity, Stewardship, and Gendered Knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 2021, 49, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, K.A.; Karamkhudoeva, M.; Ruelle, M.; Baumflek, M. Medicinal Plant Use and Health Sovereignty: Findings from the Tajik and Afghan Pamirs. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sõukand, R.; Prakofjewa, J.; Pieroni, A. The trauma of no-choice: Wild food ethnobotany in Yaghnobi and Tajik villages, Varzob Valley, Tajikistan. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 3399–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdusalam, A.; Zhang, Y.; Abudoushalamu, M.; Maitusun, P.; Whitney, C.; Yang, X.F.; Fu, Y. Documenting the heritage along the Silk Road: An ethnobotanical study of medicinal teas used in Southern Xinjiang, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Faria Lopes, S.; Ramos, M.B.; de Almeida., G.R. The Role of Mountains as Refugia for Biodiversity in Brazilian Caatinga: Conservationist Implications. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. Resilience in the mountains: Biocultural refugia of wild food in the Greater Caucasus Range, Azerbaijan. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 3529–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Topics in the Syntax of Sarikoli. Ph.D. Dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzmann, H. Linguistic diversity in space and time: A survey in the Eastern Hindukush and Karakoram. Himal. Linguist. 2005, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE). Code of Ethics. 2008. Available online: www.ethnobiology.net/whatwe-do/coreprograms/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Ali, S.I.; Qaiser, M. (Eds.) Flora of Pakistan; University of Karachi: Karachi, Pakistan, 1993–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, E.; Ali, S.I. (Eds.) Flora of Pakistan; No. 132–190; University of Karachi: Karachi, Pakistan, 1980–1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, E.; Ali, S.I. (Eds.) Flora of Pakistan; No. 191–193; University of Karachi: Karachi, Pakistan, 1989–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, E.; Ali, S.I. (Eds.) Flora of West Pakistan; No. 1–131; University of Karachi: Karachi, Pakistan, 1970–1979. [Google Scholar]

- he Plant List. Version 1.1. 2013. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Stevens, P.F. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, Version 14. 2017. Available online: http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Aziz, M.A.; Ullah, Z.; Al-Fatimi, M.; De Chiara, M.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. On the Trail of an Ancient Middle Eastern Ethnobotany: Traditional Wild Food Plants Gathered by Ormuri Speakers in Kaniguram, NW Pakistan. Biology 2021, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Abbasi, A.M.; Saeed, S.; Ahmed, A.; Pieroni, A. The Inextricable Link between Ecology and Taste: Traditional Plant Foraging in NW Balochistan, Pakistan. Econ. Bot. 2022, 76, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Zahir, H.; Amin, H.I.M.; Sõukand, R. Where tulips and crocuses are popular food snacks: Kurdish traditional foraging reveals traces of mobile pastoralism in Southern Iraqi Kurdistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T. Linguistic Genocide in Education—Or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Foner, N. The Immigrant Family: Cultural Legacies and Cultural Changes. Int. Migr. Rev. 1997, 31, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffi, L. On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge and the Environment; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bromham, L.; Dinnage, R.; Skirgård, H.; Ritchie, A.; Cardillo, M.; Meakins, F.; Greenhill, S.; Hua, X. Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghouti, I.; Cristobal, R.; Brenko, A.; Stara, K.; Markos, N.; Chapelet, B.; Hamrouni, L.; Buršić, D.; Bonet, J.A. The Market Evolution of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: A Global Supply Chain Analysis and an Application of the Delphi Method in the Mediterranean Area. Forests 2022, 13, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghouti, I.; Ouertani, E.; Guesmi, B. The Contribution of Non-Wood Forest Products to Rural Livelihoods in Tunisia: The Case of Aleppo Pine. Forests 2021, 12, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghouti, I.; Daly-Hassen, H. Essential oils value chain in Tunisian forests: Conflicts between inclusiveness and marketing performance. Arab. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 4, 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.sustainabledevelopment.un.org (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Hosagrahar, J.; Soule, J.; Girard, L.F.; Potts, A. Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda. Concept Note, ICOMOS. 2016. Available online: https://www.usicomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Final-Concept-Note.pdf/ (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Council of Europe (CoE). Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. In Faro Declaration of the Council of Europe’s Strategy for Developing Intercultural Dialogue. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

| Langauge | Village | Elevation (m.a.s.l) | Appoximate Number of Individuals | Number of Interviews | Islamic Faith | Subsistance Activites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakhi | Lashkargaz | 3658 | 2000 | 15 | Ismaili | Pastoralism/small scale horiticultural practices |

| Sarikoli | Lashkargaz | 3658 | 60 | 15 | Ismaili | Pastoralism/small scale horiticultural practices |

| Botanical Taxon; Family; Botanical Voucher; Specimen Code | Recorded Local Name | Parts Used | Recorded Local Food Uses | Sarikoli | Wakhi | Relative Frequency of Citation | Traditional Food Uses Previously Reported Among the Wakhi in North Pakistan [8] | Previously Reported Taxa among the Wakhi with Similar Local Names [8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allium carolinianum DC.;Amaryllidaceae; SWAT005988, SWAT005976, SWAT000777 | Lanturk S, W | Aerial parts | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.90 | Yes | Yes |

| Allium spp.; Amaryllidaceae; | Kach S, W | Aerial parts | Cooked S, W Salads S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.88 | Yes | Yes |

| Amaranthus cruentus L.; Amaranthaceae; SWAT005512 | Sakarghaz S, W | Aerial parts | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.65 | Yes | Yes |

| Berberis calliobotrys Bien. ex Koehne; Berberidaceae;SWAT000723 | Zolg S, W | Fruits | Raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.88 | Yes | Yes |

| Brassica rapa L.; Brassicaceae; SWAT005807, SWAT005520 | Chirogh S, W | Leaves | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.55 | Yes | Yes |

| Carum carvi L.; Apiaceae; SWAT005486 | Nirthak S, W | Seeds | Seasoning S, W Tea S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.95 | Yes | Yes |

| Chenopodium album L.; Amaranthaceae; SWAT005509, SWAT005499 | Shileet S, W | Leaves | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.68 | ||

| Cotoneaster nummularius Fish. and Mey.; Rosaceae; SWAT005485 | Dindlak S, W | Fruits | Raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.52 | Yes | Yes |

| Elaeagnus rhamnoides (L.) A.Nelson; Elaeagnaceae: SWAT005998 | Khoz gak S, W/Zakh S, W | Fruits, leaves | Fruit: raw snacks S, W, Leaves: tea S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.53 | Yes | Yes |

| Eremurus stenophyllus (Boiss. & Buhse) Baker; Xanthorrhoeaceae; SWAT005967 | Laq S, W | Leaves | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.95 | Yes | Yes |

| Lepyrodiclis holosteoides (C.A. Mey.)Fenzl ex Fisch. and C.A. Mey.;Caryophyllaceae; SWAT000747 | Yarkwush S, W | Aerial parts | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.54 | Yes | Yes |

| Malva neglecta Wallr.; Malvaceae; SWAT006043 | Swachal S, W | Leaves | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.56 | Yes | Yes |

| Medicago sativa L.; Fabaceae; SWAT005797, SWAT005795 | Wujark S, W | Aerial parts | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.58 | Yes | Yes |

| Mentha longifolia (L.) L.; Lamiaceae; SWAT005792, SWAT005790 | Wadin S, W | Aerial parts | Salads S, W | ++ | ++ | 1.00 | Yes | Yes |

| Oxyria digyna (L.) Hill.; Polygonaceae; SWAT006053 | Trush pop S, W | Leaves | Raw snacks S, W Lacto-fermentation: milk into yoghurt S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.78 | Yes | Yes |

| Papaver involucratum Popov.; Papaveraceae; SWAT000744 | Gulmarwai S, W | Flowers | Tea S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.50 | Yes | Yes |

| Polygonum spp.; Polygonaceae; SWAT006051 | Wingasgas S, W/Wingsgos S, W | Leaves | Leaves: raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.52 | Yes | Yes |

| Rheum ribes L.; Polygonaceae; SWAT004749 | Ishpat S, W | Young stems | Raw snacks S, W Lacto-fermentation: milk into yogurt S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.90 | Yes | Yes |

| Ribes alpestre Wall.ex. Decne.; Grossulariaceae; SWAT005775 | Chilazum S, W | Fruits | Raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.82 | Yes | Yes |

| Ribes orientale Desf.; Grossulariaceae; SWAT005774, SWAT005971 | Ginat S, W | Fruits | Raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.84 | Yes | Yes |

| Rosa webbiana Wall. ex Royle; Rosaceae; SWAT005502 | Charir S, W | Fruits, leaves | Fruit: raw snacks S, W Leaves: tea S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.62 | Yes | Yes |

| Rumex dentatus L.; Polygonaceae; SWAT005468 | Shalkha S, W | Leaves | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.78 | Yes | Yes |

| Taraxacum campylodes G.E.Haglund;Asteraceae; SWAT005972 | Paps/Papas S, W | Leaves | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.68 | Yes | Yes |

| Tulipa spp.; SWAT006052 | Sai shulam S, W | Raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.50 | Yes | Yes | |

| Zygophyllum obliquum Popov. Zygophyllaceae; SWAT006049 | Yum wush S, W | Aerial parts | Cooked S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.58 | Yes | Yes |

| Ziziphora clinopoides Lam. Lamiaceae; SWAT006050 | Jambilak S, W | Leaves | Tea S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.86 | Yes | Yes |

| Unidentified taxon | Jarjwush S, W | Aerial parts | Raw snacks S, W | ++ | ++ | 0.50 | Yes | Yes |

| Plant Taxa | Sarikoli | Kho | Kalasha | Kamkatawari | Wakhi | Yidgha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alluim spp. | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Amaranthus spp. | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Berberis lycium | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Brassica rapa | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| Carum carvi | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Chenopodium album | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cotoneaster nummularius | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Elaeagnus rhamnoides | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Eremurus spp. | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lepyrodiclis holosteoides | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Malva neglecta | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Medicago sativa | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Mentha longifolia | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oxyria digyna | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Papaver involucratum | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Polygonum spp. | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| Portulaca spp. | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rheum spp. | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ribes alpestre | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| Ribes orientale | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| Rosa webbiana | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Rumex spp. | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Taraxacum campylodes | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tulipa spp. | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Ziziphora clinopoides | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| Zygophyllum obliquum | + | - | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aziz, M.A.; Ullah, Z.; Adnan, M.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. Plant Use Adaptation in Pamir: Sarikoli Foraging in the Wakhan Area, Northern Pakistan. Biology 2022, 11, 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11101543

Aziz MA, Ullah Z, Adnan M, Sõukand R, Pieroni A. Plant Use Adaptation in Pamir: Sarikoli Foraging in the Wakhan Area, Northern Pakistan. Biology. 2022; 11(10):1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11101543

Chicago/Turabian StyleAziz, Muhammad Abdul, Zahid Ullah, Muhammad Adnan, Renata Sõukand, and Andrea Pieroni. 2022. "Plant Use Adaptation in Pamir: Sarikoli Foraging in the Wakhan Area, Northern Pakistan" Biology 11, no. 10: 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11101543

APA StyleAziz, M. A., Ullah, Z., Adnan, M., Sõukand, R., & Pieroni, A. (2022). Plant Use Adaptation in Pamir: Sarikoli Foraging in the Wakhan Area, Northern Pakistan. Biology, 11(10), 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11101543