Early Outcomes of Right Ventricular Pressure and Volume Overload in an Ovine Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aims

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. In Vitro Simulation of Surgical Procedures

3.2. Animal Selection

3.3. Preoperative Preparation

3.4. Anesthetic Protocol

3.4.1. Pre-Anesthetic Sedation

3.4.2. Anesthesia Induction

3.4.3. Anesthesia Maintenance

3.4.4. Animal Awakening from Anesthesia

3.4.5. Surgical Protocol

Pulmonary Artery Banding (PAB)

Pulmonary Leaflet Perforation

Pulmonary Annulotomy and Transannular Patching (TAP)

3.4.6. RV Hemodynamic and Functional Metrics

3.4.7. Intraoperative Epicardial Echocardiography

3.4.8. Postoperative Care

3.4.9. Postoperative Transthoracic Echocardiography

3.4.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

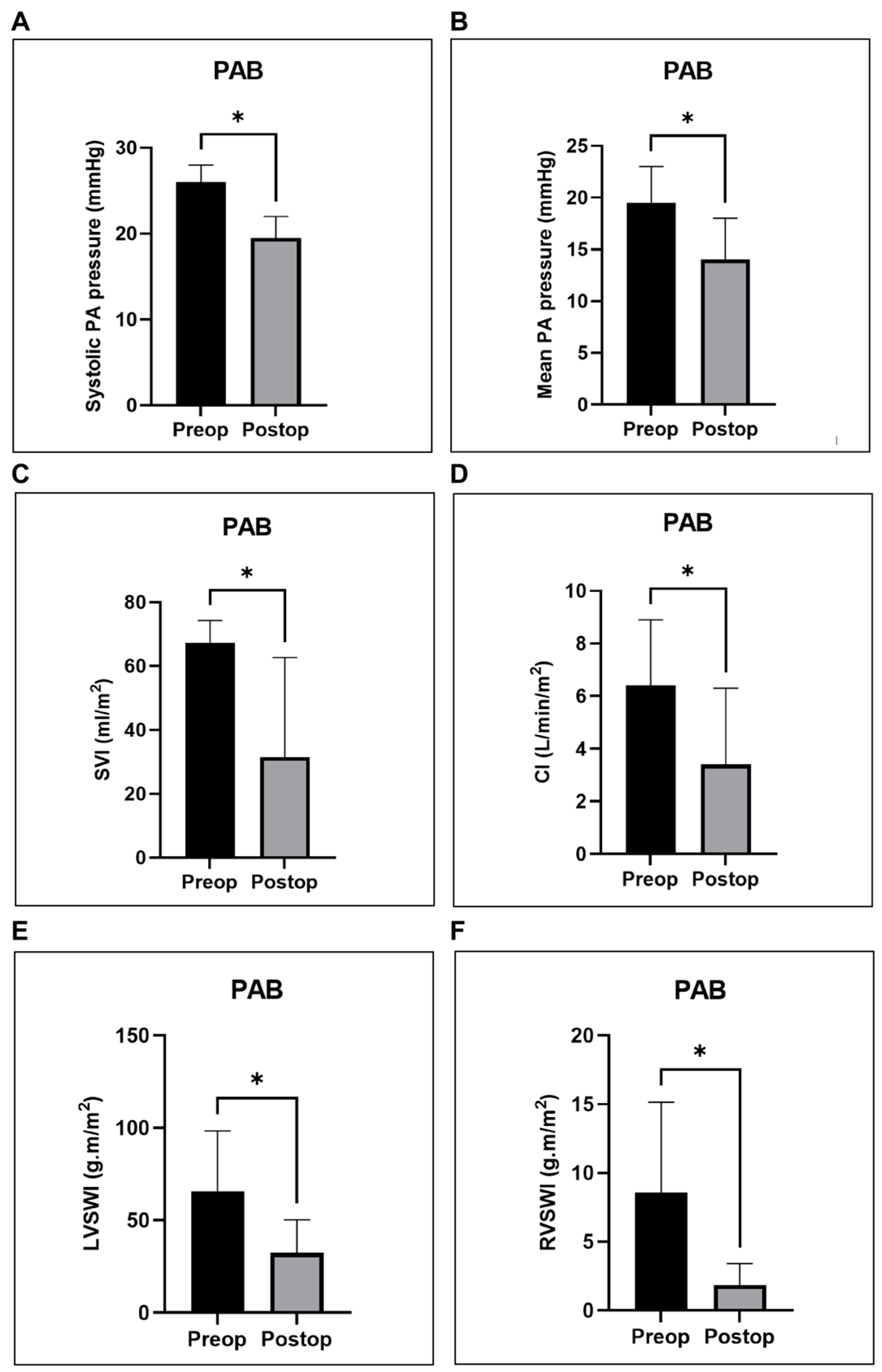

4.1. RV Hemodynamic and Functional Metrics

4.2. Postoperative Care

4.3. Complications

5. Discussion

5.1. Pathophysiology of RV Failure

5.2. Animal Models

5.3. Inducing RV Failure

5.4. Complications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHD | congenital heart disease |

| LV | left ventricle |

| RV | right ventricle |

| PAB | pulmonary artery banding |

| TAP | transannular patching |

| ETT | endotracheal tube |

| CVC | central venous catheter |

| MAPSE | mitral annular plane systolic excursion |

| TAPSE | tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

| PCV | pressure-controlled ventilation |

| TV | tidal volume |

| EtCO2 | end-tidal CO2 |

| NPO regimen | nothing by mouth |

| CVP | central venous pressure |

| CO | cardiac output |

| FiO2 | fraction of inspired oxygen |

| APL | adjustable pressure-limiting |

| RVOT | right ventricular outflow tract |

| AF | atrial fibrillation |

| ccTGA | congenitally corrected transposition of great arteries |

| TGA | transposition of great arteries |

| ASO | arterial switch operation |

| PR | pulmonary regurgitation |

| TR | tricuspid regurgitation |

| TOF | tetralogy of Fallot |

| PVRpl | pulmonary valve replacement |

| PHT | pulmonary hypertension |

| CPB | cardiopulmonary bypass |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| BP | blood pressure |

| HR | heart rate |

| ScvO2 | central venous oxygen saturation |

| SpO2 | peripheral oxygen saturation |

| SaO2 | arterial oxygen saturation |

| pO2 | oxygen partial pressure |

| pCO2 | carbon dioxide partial pressure |

| sAP | systolic arterial pressure |

| dAP | diastolic arterial pressure |

| mAP | mean arterial pressure |

| PAWP | pulmonary artery wedge pressure |

| sRVP | systolic right ventricular pressure |

| dRVP | diastolic right ventricular pressure |

| mRVP | mean right ventricular pressure |

| sPAP | systolic pulmonary artery pressure |

| dPAP | diastolic pulmonary artery pressure |

| mPAP | mean pulmonary artery pressure |

| CI | cardiac index |

| SV | stroke volume |

| SVI | stroke volume index |

| SVRI | systemic vascular resistance index |

| LCWI | left cardiac work index |

| LVSWI | left ventricular stroke work index |

| RCWI | right cardiac work index |

| RVSWI | right ventricular stroke work index |

| HCO3− | bicarbonate |

| BE | base excess |

| VA | ventriculo–arterial |

References

- Davlouros, P.A.; Niwa, K.; Webb, G.; Gatzoulis, M.A. The right ventricle in congenital heart disease. Heart 2006, 92 (Suppl. 1), i27–i38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bernstein, D.; Webber, S. New Directions in Basic Research in Hypertrophy and Heart Failure: Relevance for Pediatric Cardiology. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2011, 32, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reddy, S.; Zhao, M.; Hu, D.-Q.; Fajardo, G.; Katznelson, E.; Punn, R.; Spin, J.M.; Chan, F.P.; Bernstein, D. Physiologic and molecular characterization of a murine model of right ventricular volume overload. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 304, H1314–H1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davies, B.; Elwood, N.J.; Li, S.; Cullinane, F.; Edwards, G.A.; Newgreen, D.F.; Brizard, C.P. Human cord blood stem cells enhance neonatal right ventricular function in an ovine model of right ventricular training. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 89, 585–593.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuwenburgh, B.P.; Helbing, W.A.; Steendijk, P.; Schoof, P.H.; Baan, J. Effects of acute left ventricular unloading on right ventricular function in normal and chronic right ventricular pressure-overloaded lambs. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2003, 125, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yerebakan, C.; Klopsch, C.; Niefeldt, S.; Zeisig, V.; Vollmar, B.; Liebold, A.; Sandica, E.; Steinhoff, G. Acute and chronic response of the right ventricle to surgically induced pressure and volume overload—An analysis of pressure-volume relations. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 10, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schranz, D.; Recla, S.; Malcic, I.; Kerst, G.; Mini, N.; Akintuerk, H. Pulmonary artery banding in dilative cardiomyopathy of young children: Review and protocol based on the current knowledge. Transl. Pediatr. 2019, 8, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hon, J.K.F.; Steendijk, P.; Khan, H.; Wong, K.; Yacoub, M. Acute effects of pulmonary artery banding in sheep on right ventricle pressure-volume relations: Relevance to the arterial switch operation. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2001, 172, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerebakan, C.; Klopsch, C.; Prietz, S.; Boltze, J.; Vollmar, B.; Liebold, A.; Steinhoff, G.; Sandica, E. Pressure-volume loops: Feasible for the evaluation of right ventricular function in an experimental model of acute pulmonary regurgitation? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 9, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agger, P.; Hyldebrandt, J.A.; Nielsen, E.A.; Hjortdal, V.; Smerup, M. A novel porcine model for right ventricular dilatation by external suture plication of the pulmonary valve leaflets—Practical and reproducible. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 10, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersboell, M.; Vejlstrup, N.; Nilsson, J.C.; Kjaergaard, J.; Norman, W.; Lange, T.; Taylor, A.; Bonhoeffer, P.; Sondergaard, L. Percutaneous pulmonary valve replacement after different duration of free pulmonary regurgitation in a porcine model: Effects on the right ventricle. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 2944–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Goetze, J.P.; Søndergaard, L.; Kjaergaard, J.; Iversen, K.K.; Vejlstrup, N.G.; Hassager, C.; Andersen, C.B. Myocardial hypertrophy after pulmonary regurgitation and valve implantation in pigs. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 159, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, A.; van der Feen, D.E.; Andersen, S.; Schultz, J.G.; Hansmann, G.; Bogaard, H.J. Animal models of right heart failure. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 1561–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, V.; Capderou, A.; Le Bret, E.; Rücker-Martin, C.; Deroubaix, E.; Gouadon, E.; Raymond, N.; Stos, B.; Serraf, A.; Renaud, J.-F. Right ventricular failure secondary to chronic overload in congenital heart disease: An experimental model for therapeutic innovation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, 1197–1204.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trusler, G.A.; Mustard, W.T. A method of banding the pulmonary artery for large isolated ventricular septal defect with and without transposition of the great arteries. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1972, 13, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Lim, H.G.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, Y.J. Effects of glutaraldehyde concentration and fixation time on material characteristics and calcification of bovine pericardium: Implications for the optimal method of fixation of autologous pericardium used for cardiovascular surgery. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 24, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dayer, N.; Ltaief, Z.; Liaudet, L.; Lechartier, B.; Aubert, J.-D.; Yerly, P. Pressure Overload and Right Ventricular Failure: From Pathophysiology to Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bossers, G.P.; Hagdorn, Q.A.; Ploegstra, M.J.; Borgdorff, M.A.; Silljé, H.H.; Berger, R.M.; Bartelds, B. Volume load-induced right ventricular dysfunction in animal models: Insights in a translational gap in congenital heart disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokreisz, P.; Marsboom, G.; Janssens, S. Pressure overload-induced right ventricular dysfunction and remodelling in experimental pulmonary hypertension: The right heart revisited. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2007, 9 (Suppl. H), H75–H84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Monge García, M.I.; Santos, A. Understanding ventriculo-arterial coupling. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fourie, P.R.; Coetzee, A.R.; Bolliger, C.T. Pulmonary artery compliance: Its role in right ventricular-arterial coupling. Cardiovasc. Res. 1992, 26, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maria, M.V.; Younoszai, A.K.; Mertens, L.; Landeck, B.F., 2nd; Ivy, D.D.; Hunter, K.S.; Friedberg, M.K. RV stroke work in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension: Estimation based on invasive haemodynamic assessment and correlation with outcomes. Heart 2014, 100, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuwenburgh, B.P.; Helbing, W.A.; Steendijk, P.; Schoof, P.H.; Baan, J. Biventricular systolic function in young lambs subject to chronic systemic right ventricular pressure overload. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 281, H2697–H2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukita, R.; Tumen, A.; Stokes, J.W.; Pinelli, C.; Finnie, K.R.; Talackine, J.; Cardwell, N.L.; Wu, W.K.; Patel, Y.; Tsai, E.J.; et al. Progression Toward Decompensated Right Ventricular Failure in the Ovine Pulmonary Hypertension Model. ASAIO J. 2022, 68, e29–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ukita, R.; Stokes, J.W.; Wu, W.K.; Talackine, J.; Cardwell, N.; Patel, Y.; Benson, C.; Demarest, C.T.; Rosenzweig, E.B.; Cook, K.; et al. A Large Animal Model for Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure: Left Pulmonary Artery Ligation and Progressive Main Pulmonary Artery Banding in Sheep. J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 173, e62694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lancellotti, P.; Tribouilloy, C.; Hagendorff, A.; Moura, L.; Popescu, B.A.; Agricola, E.; Monin, J.L.; Pierard, L.A.; Badano, L.; Zamorano, J.L.; et al. European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for the assessment of valvular regurgitation. Part 1: Aortic and pulmonary regurgitation (native valve disease). Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2010, 11, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancellotti, P.; Tribouilloy, C.; Hagendorff, A.; Popescu, B.A.; Edvardsen, T.; Pierard, L.A.; Badano, L.; Zamorano, J.L. Scientific Document Committee of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: An executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 14, 611–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movileanu, I.; Harpa, M.; Al Hussein, H.; Harceaga, L.; Chertes, A.; Al Hussein, H.; Lutter, G.; Puehler, T.; Preda, T.; Sircuta, C.; et al. Preclinical testing of living tissue-engineered heart valves for pediatric patients, challenges and opportunities. Front. Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 707892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Geens, J.; Trenson, S.; Rega, F.R.; Verbeken, E.K.; Meyns, B.P. Ovine models for chronic heart failure. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2009, 32, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hussein, H.; Harpa, M.; Movileanu, I.; Al Hussein, H.; Suciu, H.; Brinzaniuc, K.; Simionescu, D. Minimally invasive surgical protocol for adipose derived stem cells collection and isolation-ovine model. Rev. Chim. 2019, 70, 1826–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hussein, H.; Al Hussein, H.; Sircuta, C.; Cotoi, O.S.; Movileanu, I.; Nistor, D.; Cordos, B.; Deac, R.; Suciu, H.; Brinzaniuc, K.; et al. Challenges in Perioperative Animal Care for Orthotopic Implantation of Tissue-Engineered Pulmonary Valves in the Ovine Model. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2020, 17, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, S.C.; Griffith, B.P.; Siewers, R.D.; Hardesty, R.L.; Ladowski, J.; Zoltun, R.A.; Neches, W.H.; Zuberbuhler, J.R. A percutaneously adjustable device for banding of the pulmonary trunk. Int. J. Cardiol. 1985, 9, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukita, R.; Tipograf, Y.; Tumen, A.; Donocoff, R.; Stokes, J.W.; Foley, N.M.; Talackine, J.; Cardwell, N.L.; Rosenzweig, E.B.; Cook, K.E.; et al. Left Pulmonary Artery Ligation and Chronic Pulmonary Artery Banding Model for Inducing Right Ventricular—Pulmonary Hypertension in Sheep. ASAIO J. 2021, 67, e44–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kuehne, T.; Saeed, M.; Gleason, K.; Turner, D.; Teitel, D.; Higgins, C.B.; Moore, P. Effects of pulmonary insufficiency on biventricular function in the developing heart of growing swine. Circulation 2003, 108, 2007–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bove, T.; Bouchez, S.; De Hert, S.; Wouters, P.; De Somer, F.; Devos, D.; Somers, P.; Van Nooten, G. Acute and chronic effects of dysfunction of right ventricular outflow tract components on right ventricular performance in a porcine model: Implications for primary repair of tetralogy of fallot. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerebakan, C.; Sandica, E.; Prietz, S.; Klopsch, C.; Ugurlucan, M.; Kaminski, A.; Abdija, S.; Lorenzen, B.; Boltze, J.; Nitzsche, B.; et al. Autologous umbilical cord blood mononuclear cell transplantation preserves right ventricular function in a novel model of chronic right ventricular volume overload. Cell Transpl. 2009, 18, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.; Greve, G.; Chen, R.; Fry, C.; Barron, D.; Lab, M.J.; A White, P.; Redington, A.N.; Penny, D.J. Right ventricular myocardial responses to chronic pulmonary regurgitation in lambs: Disturbances of activation and conduction. Pediatr. Res. 2003, 54, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zeltser, I.; Gaynor, J.W.; Petko, M.; Myung, R.J.; Birbach, M.; Waibel, R.; Ittenbach, R.F.; Tanel, R.E.; Vetter, V.L.; Rhodes, L.A. The roles of chronic pressure and volume overload states in induction of arrhythmias: An animal model of physiologic sequelae after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 130, 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Complication | Surgical Procedure Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Annulotomy + TAP (n = 4) | Pulmonary Leaflet Perforation (n = 4) | PAB (n = 6) | |

| Total arrhythmic events | 9 | 9 | 22 |

| Pre-induction (number of cases) | |||

| • Sinus bradycardia | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| • SV extrasystoles | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| • AVB grade II type I | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pre-procedure (number of cases) | |||

| • Ventricular extrasystoles | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| • SVT | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Intraprocedural (number of cases) | |||

| • Bradycardia | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| • SVT | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| • Ventricular extrasystoles | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| • ST segment elevation | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| • Atrial fibrillation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypothermia (number of cases) | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Mean central body temperature (°C) | 36.3 | 36 | 35.8 |

| Hyperthermia (number of cases) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tympanism (number of cases) | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Complication | Surgical Procedure Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Annulotomy + TAP (n = 4) | Pulmonary Leaflet Perforation (n = 4) | PAB (n = 6) | |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumothorax | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Resuscitated CA | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild fever | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Metabolic alkalosis | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Mixed alkalosis | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Hypokalemia | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Tympanism | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Constipation | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Surgical Procedure Type | Key Benefits | Key Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary Artery Banding (PAB) | - Simple surgical technique - Does not require cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) - Reproducible results for pressure overload models | - Risk of acute RV failure and arrhythmias during band tightening - Requires precise adjustment to balance between sufficient banding and hemodynamic tolerance |

| Pulmonary Leaflet Perforation | - Novel method with consistent results in inducing moderate-to-severe pulmonary regurgitation (PR) - Less invasive than TAP - Off-pump technique minimizes risks and reduces costs | - Does not replicate free PR and RVOT distortion observed in TOF repair - Limited by perforation size (aortic punch size) |

| Pulmonary Annulotomy + Transannular Patching (TAP) | - Effective in creating significant volume overload - Achieves moderate-to-severe PR - Highly reproducible outcomes - Off-pump technique minimizes risks and reduces costs | - More invasive procedure requiring RVOT incision - Longer chest drainage period and increased fluid accumulation - Higher risk of complications due to procedural complexity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Hussein, H.; Al Hussein, H.; Harpa, M.M.; Ghiragosian, S.E.R.; Gurzu, S.; Cordos, B.; Sircuta, C.; Puscas, A.I.; Anitei, D.E.; Lefter, C.; et al. Early Outcomes of Right Ventricular Pressure and Volume Overload in an Ovine Model. Biology 2025, 14, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14020170

Al Hussein H, Al Hussein H, Harpa MM, Ghiragosian SER, Gurzu S, Cordos B, Sircuta C, Puscas AI, Anitei DE, Lefter C, et al. Early Outcomes of Right Ventricular Pressure and Volume Overload in an Ovine Model. Biology. 2025; 14(2):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14020170

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Hussein, Hamida, Hussam Al Hussein, Marius Mihai Harpa, Simina Elena Rusu Ghiragosian, Simona Gurzu, Bogdan Cordos, Carmen Sircuta, Alexandra Iulia Puscas, David Emanuel Anitei, Cynthia Lefter, and et al. 2025. "Early Outcomes of Right Ventricular Pressure and Volume Overload in an Ovine Model" Biology 14, no. 2: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14020170

APA StyleAl Hussein, H., Al Hussein, H., Harpa, M. M., Ghiragosian, S. E. R., Gurzu, S., Cordos, B., Sircuta, C., Puscas, A. I., Anitei, D. E., Lefter, C., Suciu, H., Simionescu, D., & Brinzaniuc, K. (2025). Early Outcomes of Right Ventricular Pressure and Volume Overload in an Ovine Model. Biology, 14(2), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14020170