Quantitative Approaches for Exploring the Influence of Education as Positional Good for Economic Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

- The level of productivity that individuals innately possess is not influenced by their education level;

- Higher education incurs additional costs, which differ for high-productivity and low-productivity workers for the simple reason that those who learn easily can acquire skills more cheaply than others;

- Since employees know their skill level, but employers do not, asymmetric information exists concerning workers’ productivity;

- Because employers cannot observe individual workers’ actual productivity, they use their educational qualifications to predict productivity, make hiring decisions, and set wages because they assume individuals with more education are more productive.

1.2. Objective of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Research Methods

- number of years of education and

- educational position of the person in the educational distribution (share of individuals reaching at most the educational attainment of the person).

3. Results

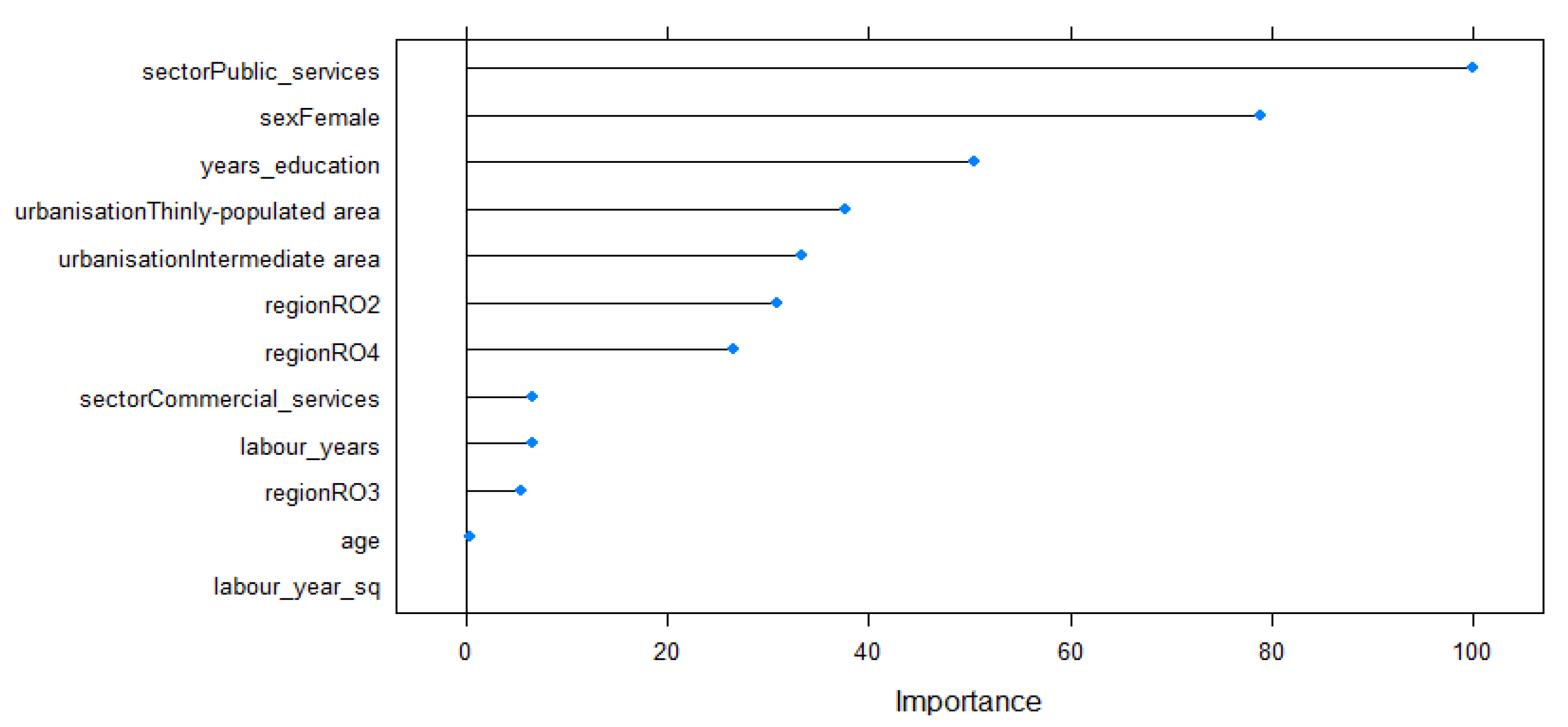

3.1. Years in Education and Wages

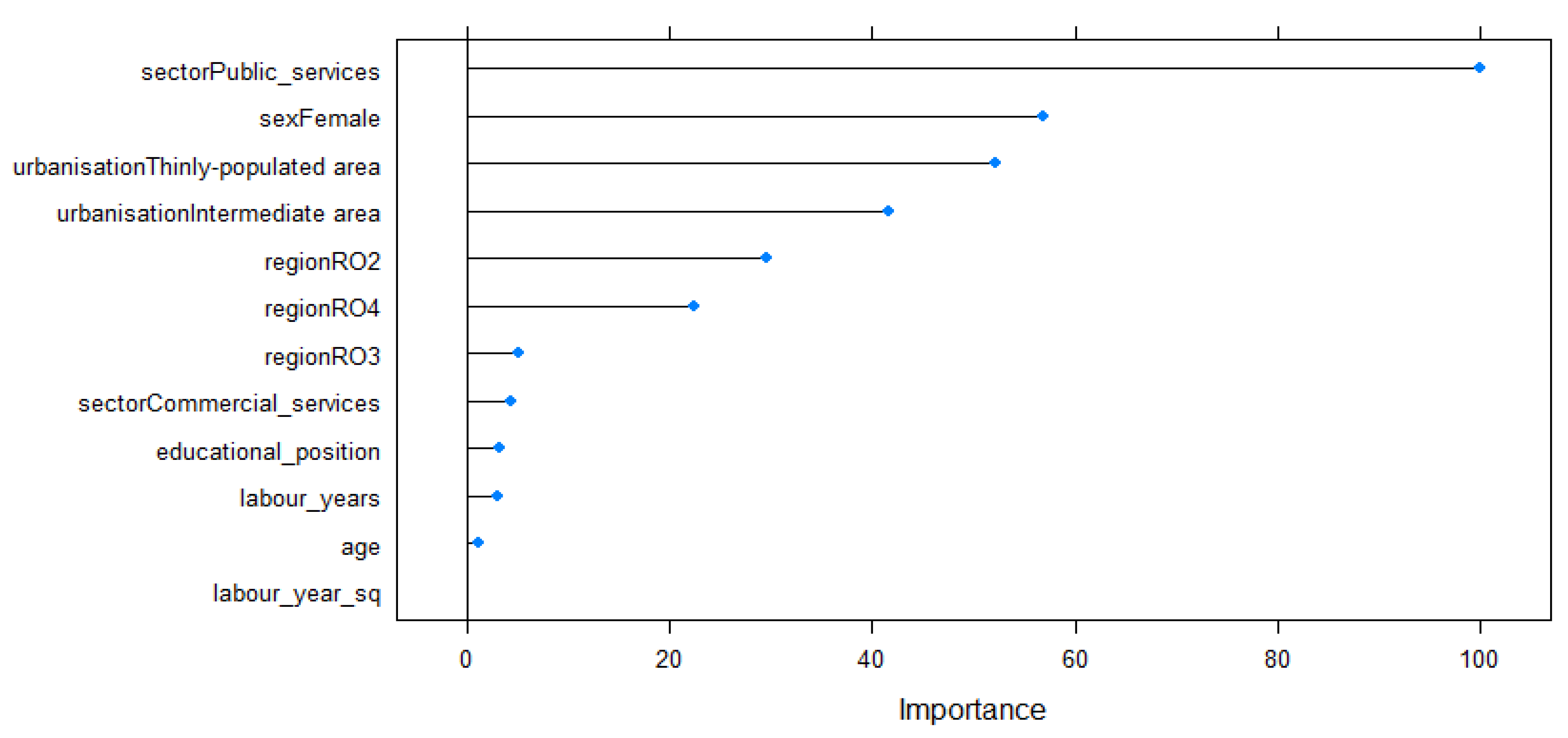

3.2. Position in Educational Distribution and Wages

3.3. Comparing the Influence of Absolute and Relative Measures of Education

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Final Reflections

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Implications

5.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bol, T. Has education become more positional? Educational expansion and labour market outcomes, 1985–2007. Acta Sociol. 2015, 58, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; Ogawa, K.; Sanfo, J.B. Educational expansion and the economic value of education in Vietnam: An instrument-free analysis. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2021, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, B.; Pospisil, R.; Dragoescu, R.M. The return to higher education: Evidence from Romania. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05076. [Google Scholar]

- Galiakberova, A.A. Conceptual analysis of education role in economics: The human capital theory. J. Hist. Cult. Art Res. 2019, 8, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hung, J.; Ramsden, M. The Application of Human Capital Theory and Educational Signalling Theory to Explain Parental Influences on the Chinese Population’s Social Mobility Opportunities. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, V.; Bol, T.; Van de Werfhorst, H.G. What makes education positional? Institutions, overeducation and the competition for jobs. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 43, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, D. Economics of education in Serbia: Between human capital and signaling and screening theories. Megatrend Rev. 2014, 11, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frazis, H. Human capital, signaling, and the pattern of returns to education. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2002, 54, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.E. Signaling in the labor market. In Economics of Education; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Jiménez, M.; Artés, J.; Salinas-Jiménez, J. Education as a positional good: A life satisfaction approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 103, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, F. Life satisfaction and education in South Africa: Investigating the role of attainment and the likelihood of education as a positional good. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lemieux, T. The “Mincer equation” thirty years after schooling, experience, and earnings. In Jacob Mincer a Pioneer of Modern Labor Economics; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinos, H.A. Estimating the Return to Schooling Using the Mincer Equation; IZA World of Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://wol.iza.org/articles/estimating-return-to-schooling-using-mincer-equation/long (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Park, T.; Carriere, K.C. Variable selection via combined penalization for high-dimensional data analysis. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2010, 54, 2230–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Trendafilov, N.T.; Uddin, M. A modified principal component technique based on the LASSO. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2003, 12, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turlach, B.A.; Venables, W.N.; Wright, S.J. Simultaneous variable selection. Technometrics 2005, 47, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Braak, C.J.F. Regression by L1 regularization of smart contrasts and sums (ROSCAS) beats PLS and elastic net in latent variable model. J. Chemom. J. Chemom. Soc. 2009, 23, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, Q. An efficient elastic net with regression coefficients method for variable selection of spectrum data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Araki, S. Beyond the high participation systems model: Illuminating the heterogeneous patterns of higher education expansion and skills diffusion across 27 countries. High. Educ. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, A.K. Education as a Positional Good? Evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 155, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q. Estimating Education and Labor Market Consequences of China’s Higher Education Expansion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, E.D.; Günther, F.; Wafaie, F. Returns to education in developing countries: Evidence from the living standards and measurement study surveys. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2015, 49, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzina, A. The increasing educational divide in the life course development of subjective wellbeing across cohorts. Acta Sociol. 2022, 65, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wincenciak, L.; Grotkowska, G.; Gajderowicz, T. Returns to education in Central and Eastern European transition economies: The role of macroeconomic context. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, A.V.; Arabsheibani, G.R.; Murphy, P. Returns to education in four transition countries. In Critical Perspectives on Economics of Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 182–212. [Google Scholar]

| Intercept | −1353.462 |

| Years in education | 532.292 |

| Labour years | 71.711 |

| Region RO2 | −326.259 |

| Region RO3 | −58.999 |

| Region RO4 | −281.407 |

| Urbanisation (intermediate area) | −351.889 |

| Urbanisation (thinly populated area) | −397.137 |

| Sector (commercial services) | −71.748 |

| Sector (public services) | 1052.452 |

| Sex (Female) | −830.274 |

| Age | 5.271 |

| Labour years squared | −1.408 |

| Intercept | 1401.591 |

| Educational position | 48.479 |

| Labour years | 44.962 |

| Region RO2 | −420.956 |

| Region RO3 | −73.207 |

| Region RO4 | −321.095 |

| Urbanisation (intermediate area) | −591.829 |

| Urbanisation (thinly populated area) | −742.176 |

| Sector (commercial services) | −64.071 |

| Sector (public services) | 1423.120 |

| Sex (Female) | −810.719 |

| Age | 18.601 |

| Labour years squared | −1.303 |

| Model M1 | Model M2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Years in education | 0.427 | |

| Educational Position | 0.288 | |

| Labour years | 0.292 | 0.184 |

| Region RO2 | −0.053 | −0.068 |

| Region RO3 | −0.010 | −0.012 |

| Region RO4 | −0.045 | −0.051 |

| Urbanisation (intermediate area) | 0.008 | 0.026 |

| Urbanisation (thinly populated area) | 0.072 | 0.135 |

| Sector (commercial services) | −0.013 | −0.012 |

| Sector (public services) | 0.151 | 0.205 |

| Sex (Female) | 0.154 | 0.151 |

| Age | 0.018 | 0.071 |

| Labour years squared | −0.247 | −0.226 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldea, A.B.; Zamfir, A.-M.; Davidescu, A.A. Quantitative Approaches for Exploring the Influence of Education as Positional Good for Economic Outcomes. Systems 2022, 10, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10060197

Aldea AB, Zamfir A-M, Davidescu AA. Quantitative Approaches for Exploring the Influence of Education as Positional Good for Economic Outcomes. Systems. 2022; 10(6):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10060197

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldea, Anamaria Beatrice, Ana-Maria Zamfir, and Adriana AnaMaria Davidescu. 2022. "Quantitative Approaches for Exploring the Influence of Education as Positional Good for Economic Outcomes" Systems 10, no. 6: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10060197

APA StyleAldea, A. B., Zamfir, A.-M., & Davidescu, A. A. (2022). Quantitative Approaches for Exploring the Influence of Education as Positional Good for Economic Outcomes. Systems, 10(6), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems10060197